Laparoendoscopic Single-Site Surgery Versus Conventional Laparoscopic Surgery in Ovarian Cystectomy: A Meta-Analysis

Highlights

- Laparoendoscopic single-site (LESS) ovarian cystectomy significantly reduces hospital stay by an average of 0.26 days compared to conventional multi-port laparoscopy.

- LESS cystectomy increases operative time by an average of 9.42 min but shows no significant differences in postoperative pain, blood loss, or complication rates versus conventional laparoscopy.

- LESS surgery provides a meaningful recovery advantage through shorter hospitalization with comparable safety and postoperative pain profiles.

- Despite longer operative times, LESS ovarian cystectomy is confirmed as a reliable and cosmetically superior alternative to conventional laparoscopy for benign ovarian cysts.

Abstract

1. Introduction

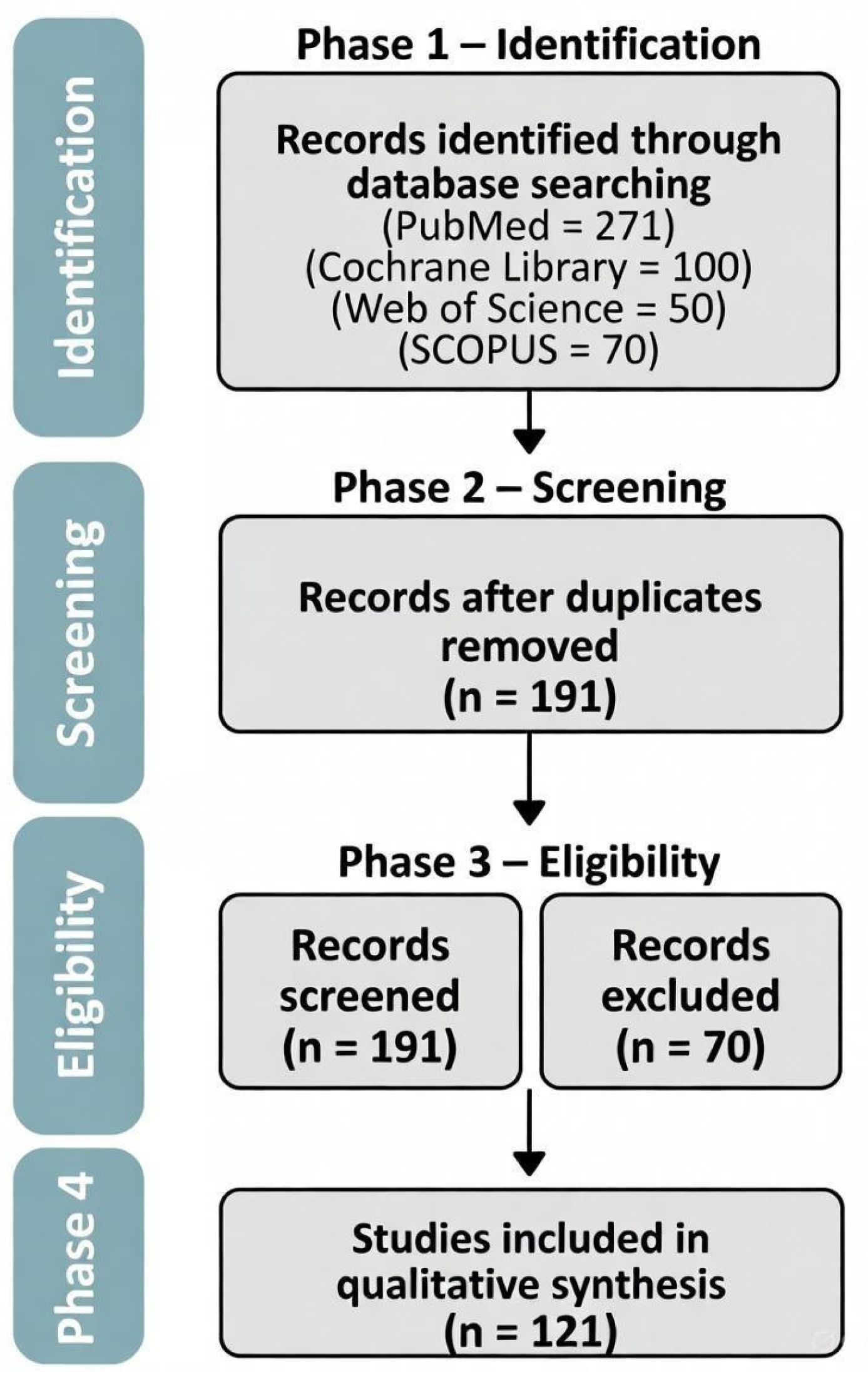

2. Methods

- Subjects: Females with non-malignant ovarian growths undergoing excision without tube removal, ovary removal, or combined.

- Approach: Single-port endoscopic procedure (LESS).

- Comparison: Multi-port laparoscopic method (CLS).

- Parameters: Indicators of operational outcomes (e.g., duration, fluid loss), postoperative discomfort, issues, and recuperation indicators (e.g., inpatient time).

- Format: We incorporated randomized trials (RCTs) and non-randomized investigations.

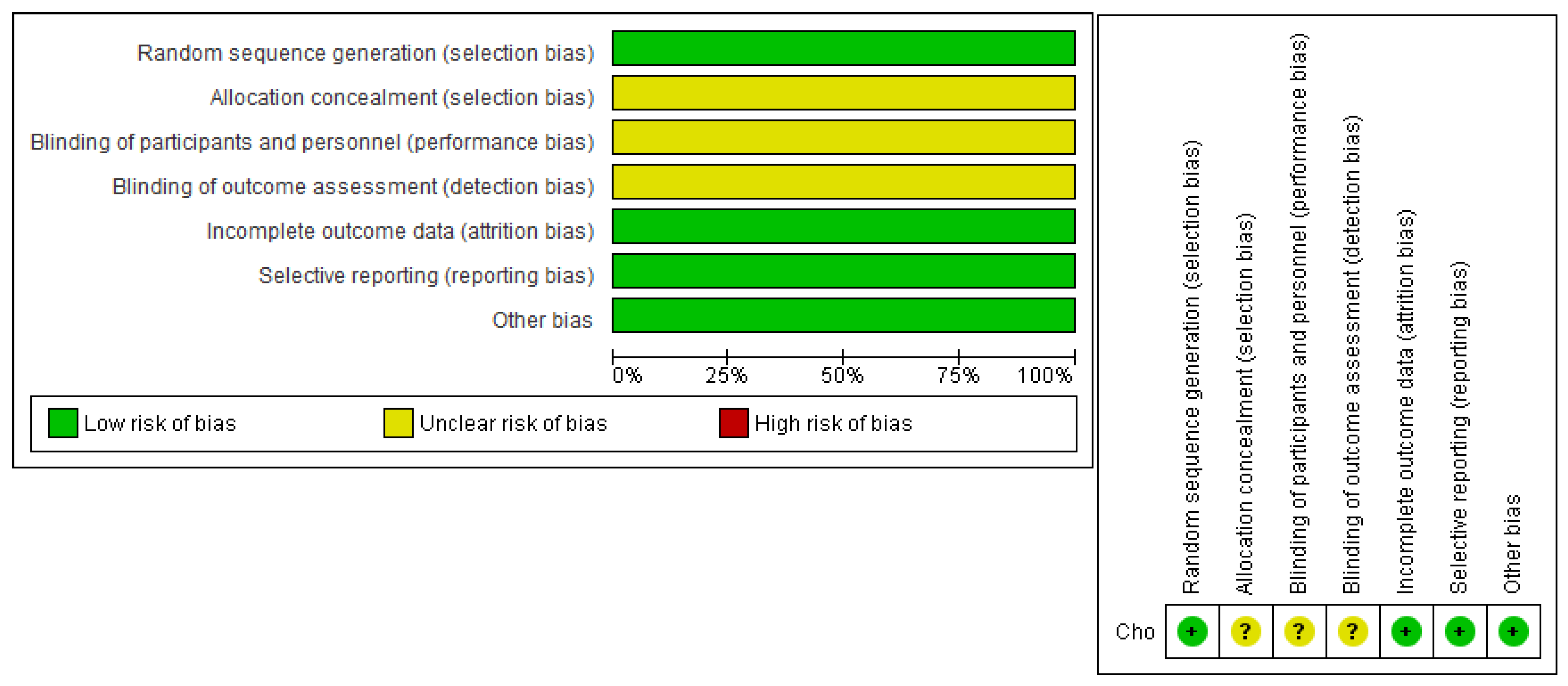

2.1. Quality Assessment

2.2. Data Collection

- −

- Demographic Details: This encompassed basic traits of the subjects, such as age and weight measures.

- −

- Parameters: Information on duration, fluid loss, postoperative discomfort (gauged by the Visual Scale, VAS), issue rates, and inpatient length.

- −

- Quality Appraisal Information: Details from the quality assessment of each investigation.

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Summary of the Included Studies

3.2. The Results of the Quality Assessment

3.3. Analysis of Outcomes

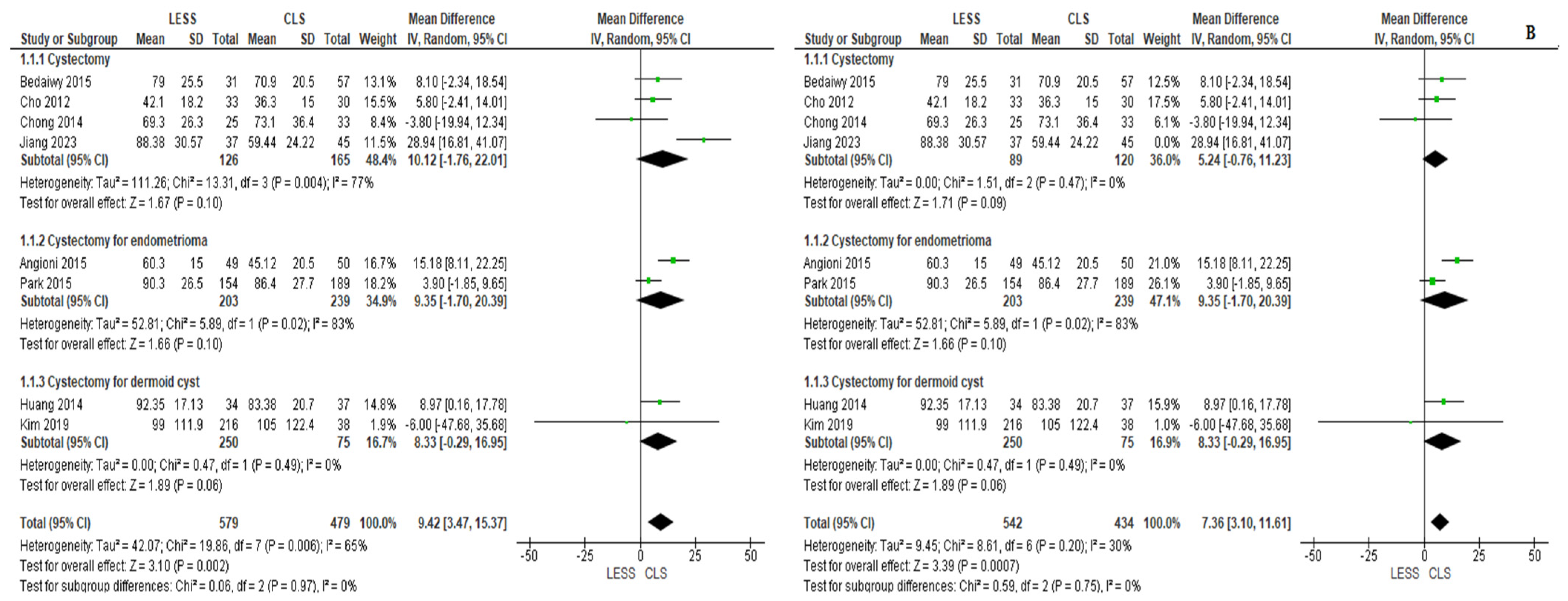

- Complete Operative Time (in Minutes)

- 2.

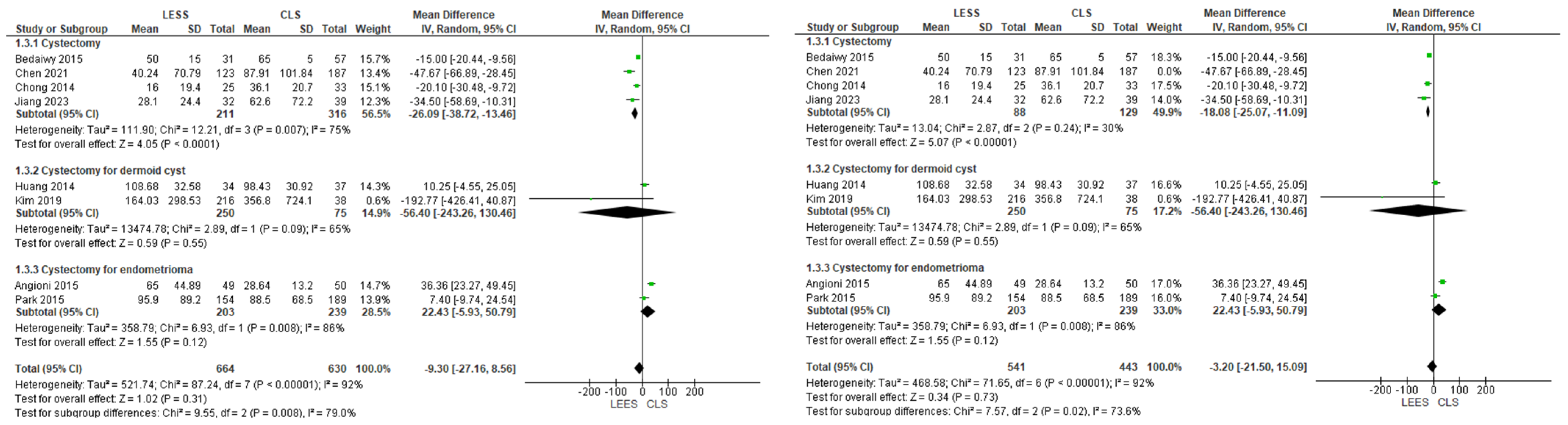

- Approximated Blood Loss (EBL) (in mL)

- 3.

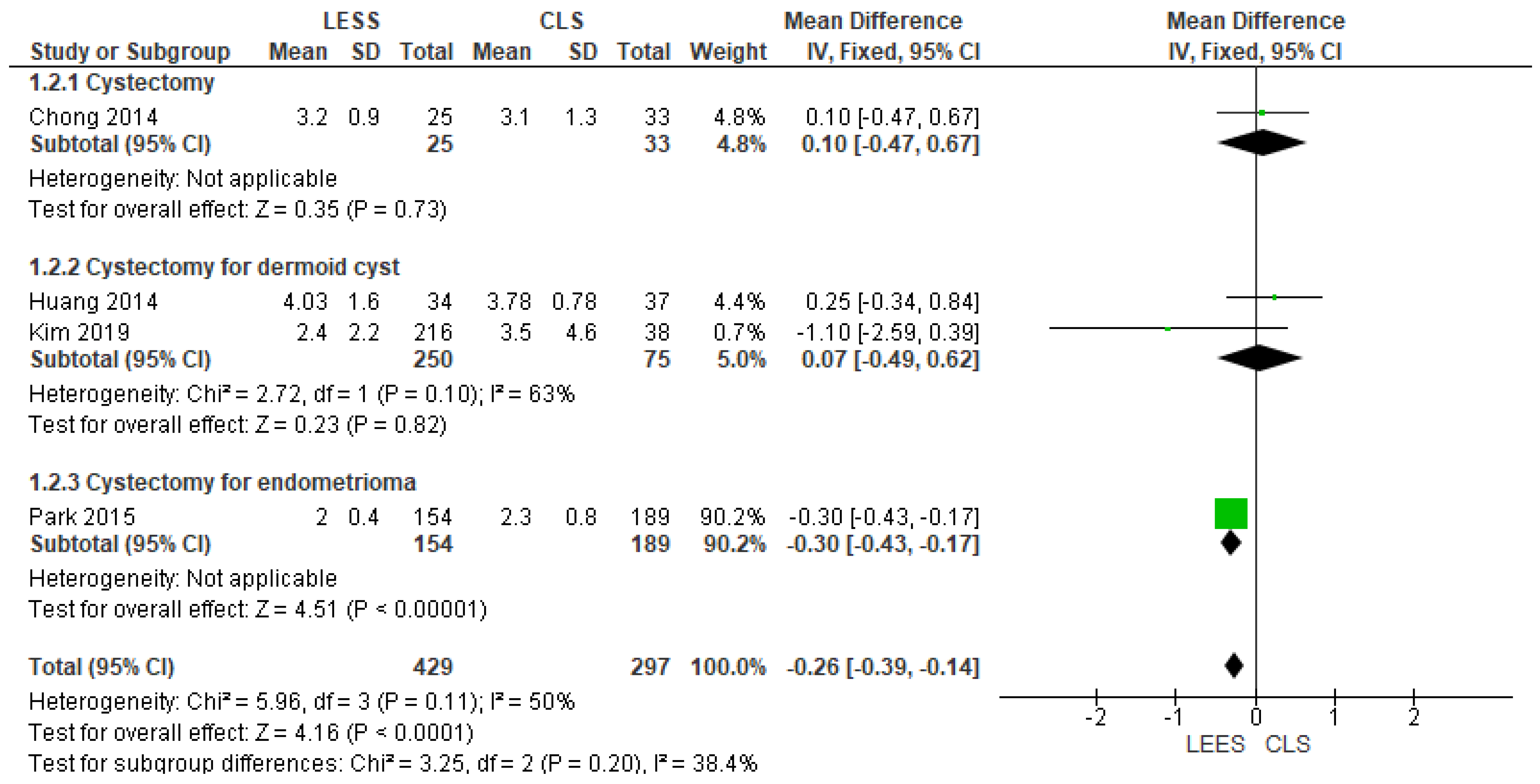

- Complete Length of Hospital Time (in Days)

- 4.

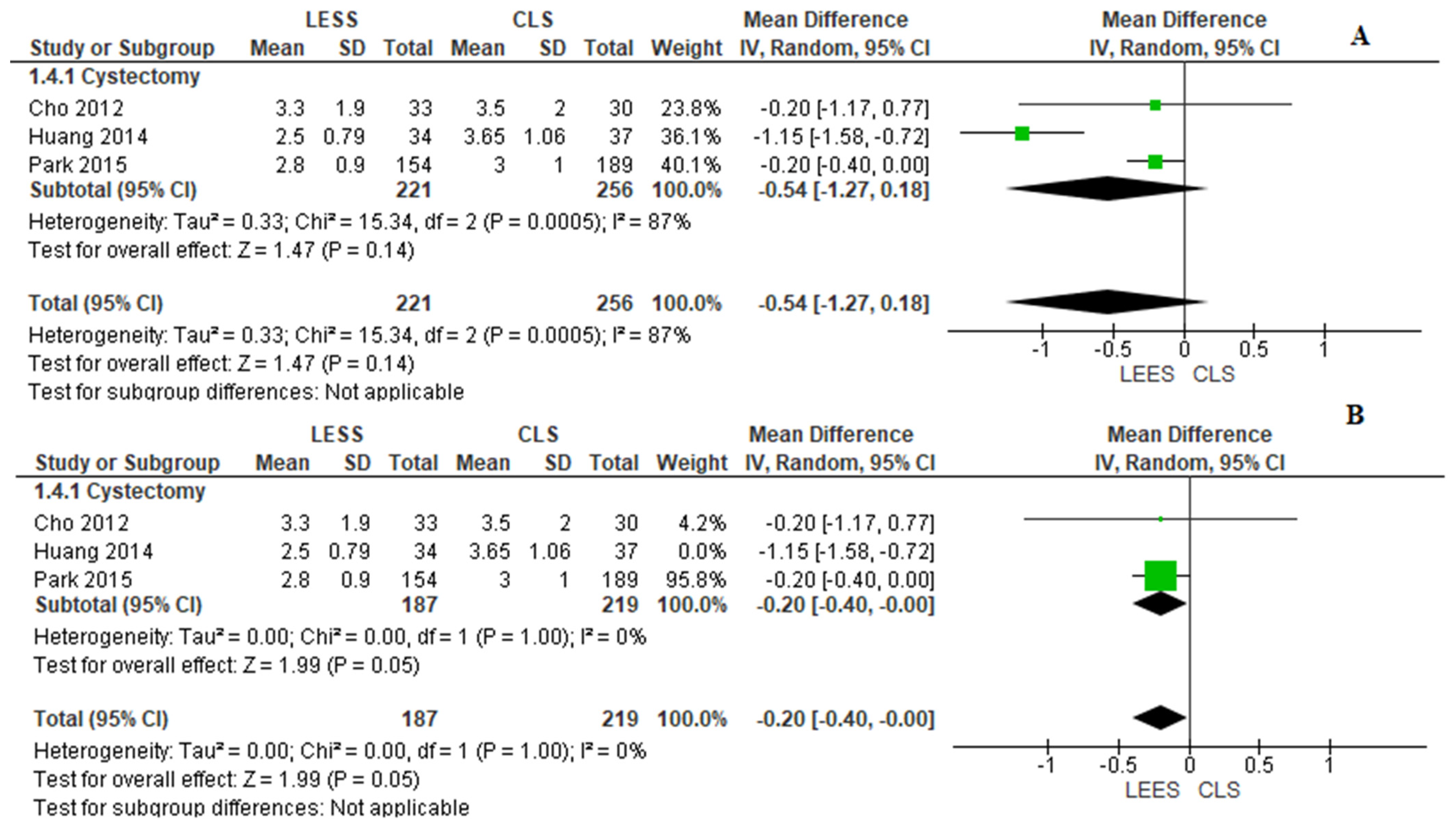

- VAS Pain Scale Rating 24 h After Operation

- 5.

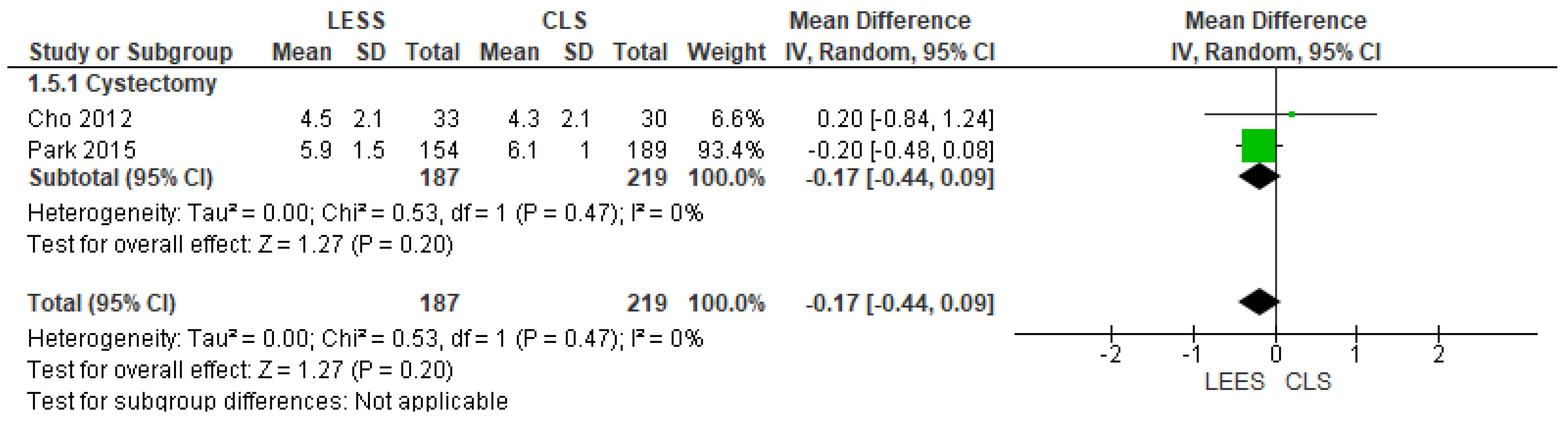

- VAS Pain Scale Rating 6 h After Operation

- 6.

- Opioid Pain Relief Usage

- 7.

- Change in Hemoglobin Level (HB) (in g/dL)

- 8.

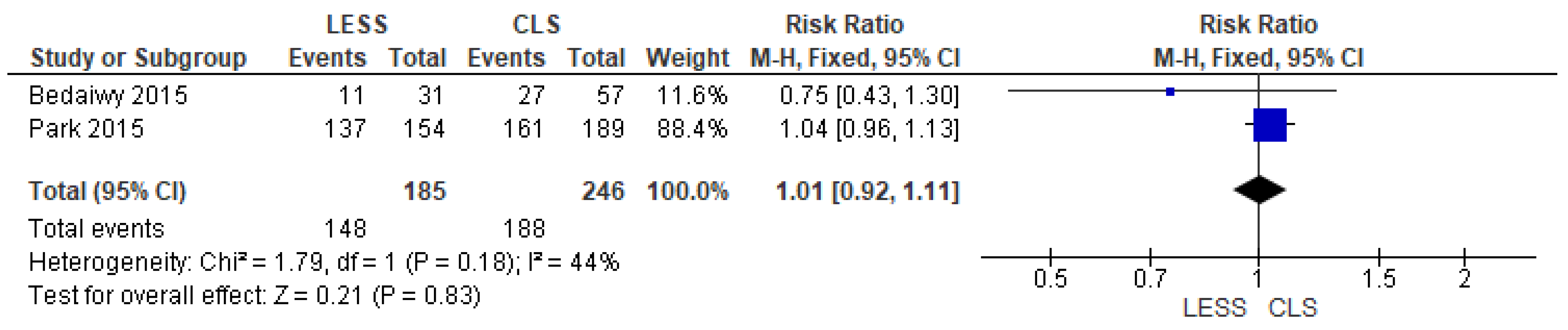

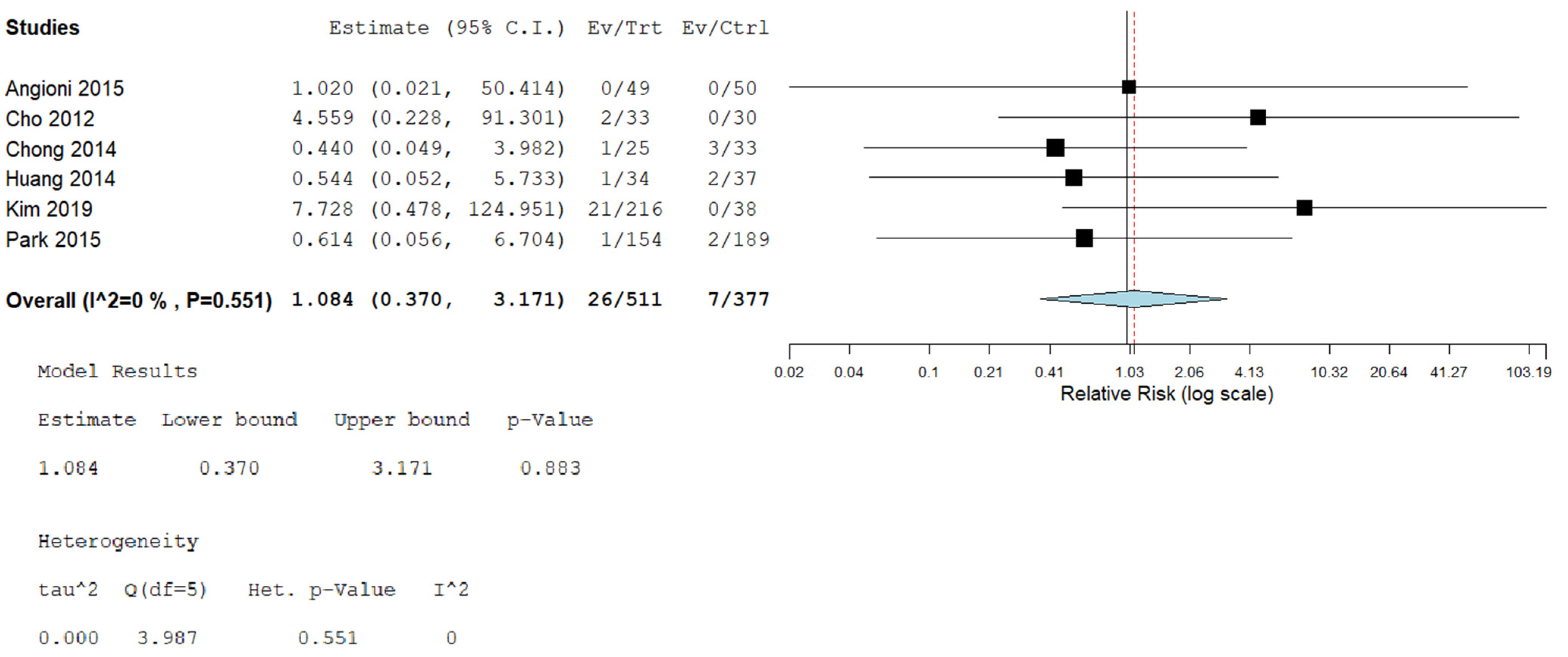

- Postoperative Complications

4. Discussion

5. Comparison of Recent Literature

6. Limitations

7. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Jeon, H.G.; Jeong, W.; Oh, C.K.; Lorenzo, E.I.S.; Ham, W.S.; Rha, K.H.; Han, W.K. Initial Experience with 50 Laparoendoscopic Single Site Surgeries Using a Homemade, Single Port Device at a Single Center. J. Urol. 2010, 183, 1866–1872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, M.-P.; Wu, C.-J.; Long, C.-Y.; Ho, C.-H.; Huang, K.-H.; Chu, C.-C.; Chou, C.-Y. Surgical trends for benign ovarian tumors among hospitals of different accreditation levels: An 11-year nationwide population-based descriptive study in Taiwan. Taiwan. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2013, 52, 498–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, C.C. A comparison of the costs of laparoscopic myomectomy and open myomectomy at a teaching hospital in southern Taiwan. Taiwan. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2013, 52, 227–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, X.; Zuo, X.; Zhu, H. Laparoendoscopic Single-Site Technique Contrasted with Conventional Laparoscopy in Cystectomy for Benign Ovarian Cysts. Curr. Ther. Res. 2023, 99, 100713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bedaiwy, M.A.; Sheyn, D.; Eghdami, L.; Abdelhafez, F.F.; Volsky, J.G.; Nickles-Fader, A.; Escobar, P.F. Laparoendoscopic single-site surgery for benign ovarian cystectomies. Gynecol. Obstet. Investig. 2015, 79, 179–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, J.-Y.; Kim, D.-Y.; Kim, S.-H.; Suh, D.-S.; Kim, J.-H.; Nam, J.-H. Laparoendoscopic single-site compared with conventional laparoscopic ovarian cystectomy for ovarian endometrioma. J. Minim. Invasive Gynecol. 2015, 22, 813–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Wen, M.K.; Liu, H.Y.; Sun, D.W.; Lang, J.H.; Fan, Q.B.; Shi, H.H. Clinical retrospective control study of single-port laparoendoscopic and multi-port laparoscopic ovarian cystectomy. Zhonghua Fu Chan Ke Za Zhi 2017, 52, 675–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, B.S.; Park, H.; Seong, S.J.; Park, C.T.; Park, S.W.; Lee, K.J. Single-Port Laparoscopic Salpingectomy for the Surgical Treatment of Ectopic Pregnancy. J. Minim. Invasive Gynecol. 2010, 17, 26–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, M.C.; Kim, T.-J.; Kang, S.; Bae, D.-S.; Park, S.-Y.; Seo, S.-S. Embryonic natural orifice transumbilical endoscopic surgery (E-NOTES) for adnexal tumors. Surg Endosc. 2009, 23, 2445–2449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, T.-J.; Lee, Y.-Y.; Kim, M.J.; Kim, C.J.; Kang, H.; Choi, C.H.; Lee, J.-W.; Kim, B.-G.; Bae, D.-S. Single Port Access Laparoscopic Adnexal Surgery. J. Minim. Invasive Gynecol. 2009, 16, 612–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.-Y.; Kim, T.-J.; Kim, C.J.; Kang, H.; Choi, C.H.; Lee, J.-W.; Kim, B.-G.; Lee, J.-H.; Bae, D.-S. Single-Port Access Laparoscopic-Assisted Vaginal Hysterectomy: A Novel Method with a Wound Retractor and a Glove. J. Minim. Invasive Gynecol. 2009, 16, 450–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koyanagi, T.; Motomura, S. Transumbilical single-incision laparoscopic surgery: Application to laparoscopically assisted vaginal hysterectomy. Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 2011, 283, 305–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, Y.W.; Kim, Y.T.; Lee, D.W.; Hwang, Y.I.; Nam, E.J.; Kim, J.H.; Kim, S.W. The feasibility of scarless single-port transumbilical total laparoscopic hysterectomy: Initial clinical experience. Surg. Endosc. 2010, 24, 1686–1692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moher, D. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement (Chinese edition). J. Chin. Integr. Med. 2009, 7, 889–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Booth, A.; Clarke, M.; Dooley, G.; Ghersi, D.; Moher, D.; Petticrew, M.; Stewart, L. The nuts and bolts of PROSPERO: An international prospective register of systematic reviews. Syst. Rev. 2012, 1, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Study Quality Assessment Tools. Bethesda: U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. Available online: https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health-topics/study-quality-assessment-tools (accessed on 6 July 2025).

- Angioni, S.; Pontis, A.; Cela, V.; Sedda, F.; Genazzani, A.D.; Nappi, L. Surgical technique of endometrioma excision impacts on the ovarian reserve. Single-port access laparoscopy versus multiport access laparoscopy: A case control study. Gynecol. Endocrinol. 2015, 31, 454–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Q.; Zhu, S.; Wang, D.; Chen, M.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, Q. Hidden blood loss and its risk factors in patients undergoing conventional laparoscopic surgery and laparoendoscopic single-site surgery for ovarian cystectomy. Int. J. Gynecol. Obstet. 2022, 157, 424–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cho, Y.J.; Kim, M.-L.; Lee, S.Y.; Lee, H.S.; Kim, J.M.; Joo, K.Y. Laparoendoscopic single-site surgery (LESS) versus conventional laparoscopic surgery for adnexal preservation: A randomized controlled study. Int. J. Womens Health 2012, 4, 85–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chong, G.O.; Hong, D.G.; Lee, Y.S. Single-port (octoport) assisted extracorporeal ovarian cystectomy for the treatment of large ovarian cysts: Compare to conventional laparoscopy and laparotomy. J. Minim. Invasive Gynecol. 2015, 22, 45–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, B.-S.; Wang, P.-H.; Tsai, H.-W.; Hsu, T.-F.; Yen, M.-S.; Chen, Y.-J. Single-port compared with conventional laparoscopic cystectomy for ovarian dermoid cysts. Taiwan J. Obs. Gynecol. 2014, 53, 523–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, T.-J.; Kim, M.; Choi, C.; Lee, J.-W.; Kim, B.-G.; Bae, D.-S. Comparison between laparoendoscopic single-site and conventional laparoscopic surgery in mature cystic teratoma of the ovary. Gynecol. Minim. Invasive Ther. 2019, 8, 155–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wallace, B.C.; Dahabreh, I.J.; Trikalinos, T.A.; Lau, J.; Trow, P.; Schmid, C.H. Closing the Gap between Methodologists and End-Users: R as a Computational Back-End. J. Stat. Softw. 2012, 49, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.; Liu, M.; Ye, H.; He, J.; Chen, J. Laparoendoscopic single-site surgery compared with conventional laparoscopic surgery for benign ovarian masses: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open 2020, 10, e032331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitt, A.; Crochet, P.; Knight, S.; Tourette, C.; Loundou, A.; Agostini, A. Single-Port Laparoscopy vs. Conventional Laparoscopy in Benign Adnexal Diseases: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Minim. Invasive Gynecol. 2017, 24, 1083–1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fagotti, A.; Rossitto, C.; Marocco, F.; Gallotta, V.; Bottoni, C.; Scambia, G.; Fanfani, F. Perioperative Outcomes of Laparoendoscopic Single-Site Surgery (LESS) Versus Conventional Laparoscopy for Adnexal Disease: A Case—Control Study. Surg. Innov. 2011, 18, 29–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yim, G.W.; Lee, M.; Nam, E.J.; Kim, S.; Kim, Y.T.; Kim, S.W. Is Single-Port Access Laparoscopy Less Painful Than Conventional Laparoscopy for Adnexal Surgery? A Comparison of Postoperative Pain and Surgical Outcomes. Surg. Innov. 2013, 20, 46–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Study ID | Country | Included Population | Intervention | Study Design | Sample Size LESS | Sample Size CLS | Age (Mean, SD/(IQR)) LESS | Age (Mean, SD/(IQR)) CLS | BMI (Mean, SD/(IQR)) LESS | BMI (Mean, SD/(IQR)) CLS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Angioni 2015 [17] | Italy | Patients aged 18–45 years; unilateral endometrioma greater than 35 mm; no previous gynecological surgery or hormonal therapy 3 months before surgery. | Cystectomy for unilateral endometrioma | Prospective case–control study | 49 | 50 | 30.25 ± 5.10 | 30.53 ± 4.55 | 20.42 ± 2.30 | 20.19 ± 2.58 |

| Bedaiwy 2015 [5] | USA | Patients undergoing ovarian cystectomy for benign disease. | Cystectomy | Retrospective cohort | 31 | 57 | 32 ± 5 | 34 ± 5 | 27 ± 3 | 28 ± 4 |

| Chen 2022 [18] | China | Patients who underwent ovarian cystectomy by CLS or LESS. | Cystectomy | Retrospective cohort study | 123 | 187 | 30.36 ± 7.36 | 30.88 ± 6.25 | 21.44 ± 3.77 | 21.58 ± 3.22 |

| Cho 2012 [19] | Korea | Patients aged between 18 and 45 years; premenopausal status; presence of a unilateral adnexal mass, the largest diameter of the unilateral adnexal mass ranging between 4 cm and 10 cm in imaging studies; and normal cancer antigen (CA)-125 levels. | Cyst enucleation of a unilateral benign adnexal mass | RCT | 33 | 30 | 29.5 ± 6.2 | 31.1 ± 7.2 | 21.4 ± 3.2 | 22.5 ± 3.3 |

| Chong 2015 [20] | South Korea | Patients underwent cystectomy for the treatment of large ovarian cysts. | Extracorporeal cystectomy | Retrospective cohort study | 25 | 33 | 23.3 ± 8.3 | 22.3 ± 4.5 | 21.1 ± 3.1 | 22.5 ± 3 |

| Huang 2014 [21] | Taiwan | Patients receiving cystectomy for ovarian dermoid cysts. | Ovarian dermoid cystectomy | Retrospective case–control study | 34 | 37 | 34.59 ± 10.18 | 34.73 ± 9.68 | 21.29 ± 2.52 | 21.14 ± 2.61 |

| Jiang 2023 [4] | China | Patients aged 18–50 years; BMI ≤ 35; no acute infection or serious chronic disease, and ovarian cysts ≤ 15 cm in diameter. | Cystectomy | Retrospective cohort study | 37 | 45 | 31.05 ± 8.28 | 34.11 ± 7.32 | 21.93 ± 3.37 | 22.46 ± 3.10 |

| Kim 2019 [22] | Korea | Patients who underwent surgery (cystectomy) for ovarian mature cystic teratoma. | Ovarian dermoid cystectomy | Retrospective cohort study | 216 | 38 | 29.2 (8–49) | 31.6 (10–47) | 21.5 (14.3–38.4) | 22.7 (17.2–31.5) |

| Park 2015 [6] | Korea | Patients who underwent laparoscopic surgery due to ovarian endometriomas. | Cystectomy of endometrioma | Retrospective study | 154 | 189 | 35.3 ± 6.9 | 33.4 ± 7.1 | 21.74 ± 7.9 | 21.25 ± 6.3 |

| Study ID | Previous Abdominal Surgery LESS | Previous Abdominal Surgery CLS | Mass Size (cm) LESS | Mass Size (cm) CLS | Mature Cystic Teratoma LESS | Mature Cystic Teratoma CLS | Mucinous Cystadenoma LESS | Mucinous Cystadenoma CLS | Serous Cystadenoma LESS | Serous Cystadenoma CLS | Others LESS | Others CLS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Angioni 2015 [17] | NR | NR | 7.60 ± 3.56 | 7 ± 2 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Bedaiwy 2015 [5] | 11 (35.4) | 19 (33.3) | 6.5 ± 2.1 | 7.2 ± 2.1 | 10 (32.3) | 21 (37) | 8 (15.7) | 13 (22.9) | 9 (29) | 14 (24.7) | 4 (13) | 9 (15.9) |

| Chen 2022 [18] | NR | NR | NR | NR | 53 | 45 | NR | NR | NR | NR | 41 | 91 |

| Cho 2012 [19] | 4 (12.1%) | 5 (16.7%) | 6.6 ± 1.6 | 7.0 ± 1.7 | 22 (66.7%) | 19 (63.3%) | 3 (9.1%) | 2 (6.7%) | 4 (12.1%) | 5 (16.7%) | 4 (12.1%) | 4 (13.3%) |

| Chong 2015 [20] | NR | NR | 11.4 ± 4.2 | 9.7 ± 2.3 | 18 (72) | 25 (76) | 5 (20) | 4 (12) | 1 (4) | 4 (12) | 1 (4) | 0 |

| Huang 2014 [21] | 7 (20.6) | 4 (10.8) | 7.05 ± 2.37 | 6.39 ± 2.27 | 34 (100) | 37 (100) | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Jiang 2023 [4] | 14 (37.8) | 15 (33.3) | 5.86 ± 3.24 | 5.91 ± 1.94 | 22 (59.5) | 21 (46.7) | 4 (10.8) | 4 (8.9) | 3 (8.1) | 4 (8.9) | 8 (22) | 16 (35.6) |

| Kim 2019 [22] | 21 (9.7) | 6 (15.7) | 7.2 (13.0–67.7) | 7.51 (34.0–178.0) | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Park 2015 [6] | 12 (7.8) | 9 (4.8) | 5.7 ± 2.1 | 6.1 ± 2.1 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Question | Angioni 2015 [17] | Bedaiwy 2015 [5] | Chen 2022 [18] | Chong 2015 [20] | Huang 2014 [21] | Jiang 2023 [4] | Kim 2019 [22] | Park 2015 [6] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Was the research question or objective in this paper clearly stated? | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 2. Was the study population clearly specified and defined? | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 3. Was the participation rate of eligible people at least 50%? | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 4. Were all the subjects selected or recruited from the same or similar populations (including the same time period)? Were the inclusion and exclusion criteria for being in the study prespecified and applied uniformly to all participants? | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 5. Was a sample size justification, power description, or variance and effect estimates provided? | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 6. For the analysis in this paper, were the exposure (s) of interest measured before the outcome(s) being measured? | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 7. Was the timeframe sufficient so that one could reasonably expect to see an association between exposure and outcome if it existed? | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 8. For exposures that can vary in amount or level, did the study examine different levels of exposure as related to the outcome (e.g., categories of exposure, or exposure measured as a continuous variable)? | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 9. Were the exposure measures (independent variables) clearly defined, valid, reliable, and implemented consistently across all study participants? | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 10. Was the exposure(s) assessed more than once over time? | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 11. Were the outcome measures (dependent variables) clearly defined, valid, reliable, and implemented consistently across all study participants? | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 12. Were the outcome assessors blinded to the exposure status of participants? | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * |

| 13. Was the loss to follow-up after baseline 20% or less? | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 14. Were key potential confounding variables measured and adjusted statistically for their impact on the relationship between exposure(s) and outcome(s)? | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Total score (out of 14) | 10/14 | 10/14 | 10/14 | 11/14 | 10/14 | 11/14 | 11/14 | 11/14 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Marchand, G.J.; Abdelsattar, A.T.; Gonzalez Herrera, D.; Robinson, M.; Kline, E.; Mera, S.; Koshaba, M.; Pulicherla, N.; Azadi, A. Laparoendoscopic Single-Site Surgery Versus Conventional Laparoscopic Surgery in Ovarian Cystectomy: A Meta-Analysis. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 8739. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14248739

Marchand GJ, Abdelsattar AT, Gonzalez Herrera D, Robinson M, Kline E, Mera S, Koshaba M, Pulicherla N, Azadi A. Laparoendoscopic Single-Site Surgery Versus Conventional Laparoscopic Surgery in Ovarian Cystectomy: A Meta-Analysis. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(24):8739. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14248739

Chicago/Turabian StyleMarchand, Greg J., Ahmed T. Abdelsattar, Daniela Gonzalez Herrera, Mckenna Robinson, Emily Kline, Sarah Mera, Michelle Koshaba, Nidhi Pulicherla, and Ali Azadi. 2025. "Laparoendoscopic Single-Site Surgery Versus Conventional Laparoscopic Surgery in Ovarian Cystectomy: A Meta-Analysis" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 24: 8739. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14248739

APA StyleMarchand, G. J., Abdelsattar, A. T., Gonzalez Herrera, D., Robinson, M., Kline, E., Mera, S., Koshaba, M., Pulicherla, N., & Azadi, A. (2025). Laparoendoscopic Single-Site Surgery Versus Conventional Laparoscopic Surgery in Ovarian Cystectomy: A Meta-Analysis. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(24), 8739. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14248739