Comparative Efficacy and Safety of Once-Weekly Pegylated Recombinant Human Growth Hormone Versus Daily Growth Hormone Therapy in Children: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Search Strategy

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

- Population: Pediatric patients (≤18 years) diagnosed with GHD or ISS.

- Intervention: Once-weekly PEG-rhGH administered at any dose.

- Comparator: Either conventional once-daily rhGH or a different PEG-rhGH dosing regimen.

- Outcomes: Studies reporting at least one relevant outcome, including height SDS, height velocity (cm/year), or IGF-1 SDS.

- Design: Randomized controlled trials (RCTs), prospective non-randomized controlled studies, or retrospective cohort studies with a control or comparison group.

- Adult populations (>18 years).

- Non-pegylated long-acting GH analogs (e.g., somapacitan, or somatrogon).

- Case reports, reviews, or conference abstracts without full data.

- Duplicate publications from overlapping cohorts.

2.3. Study Selection and Screening

2.4. Data Extraction

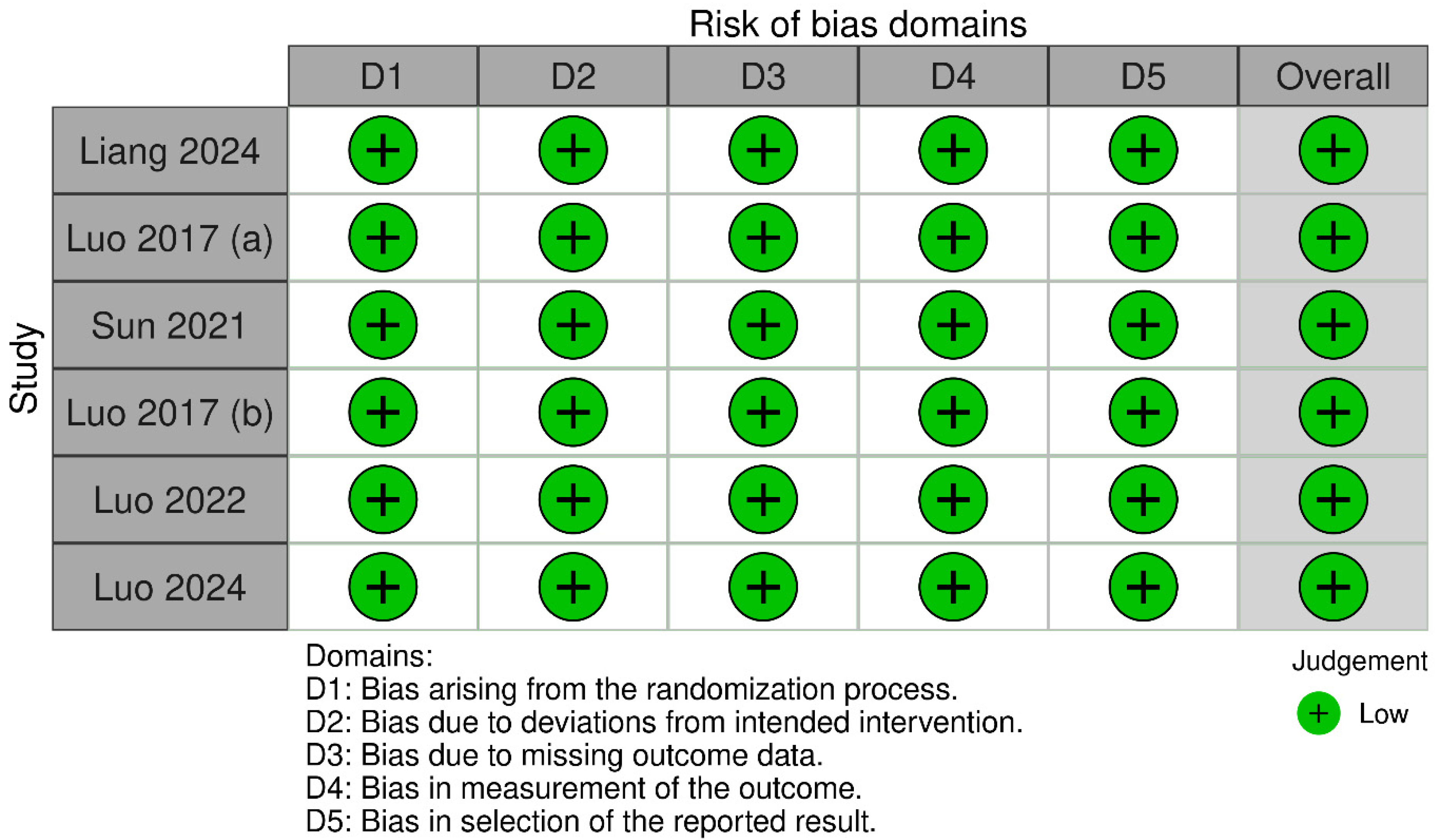

2.5. Quality Assessment and Risk of Bias

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

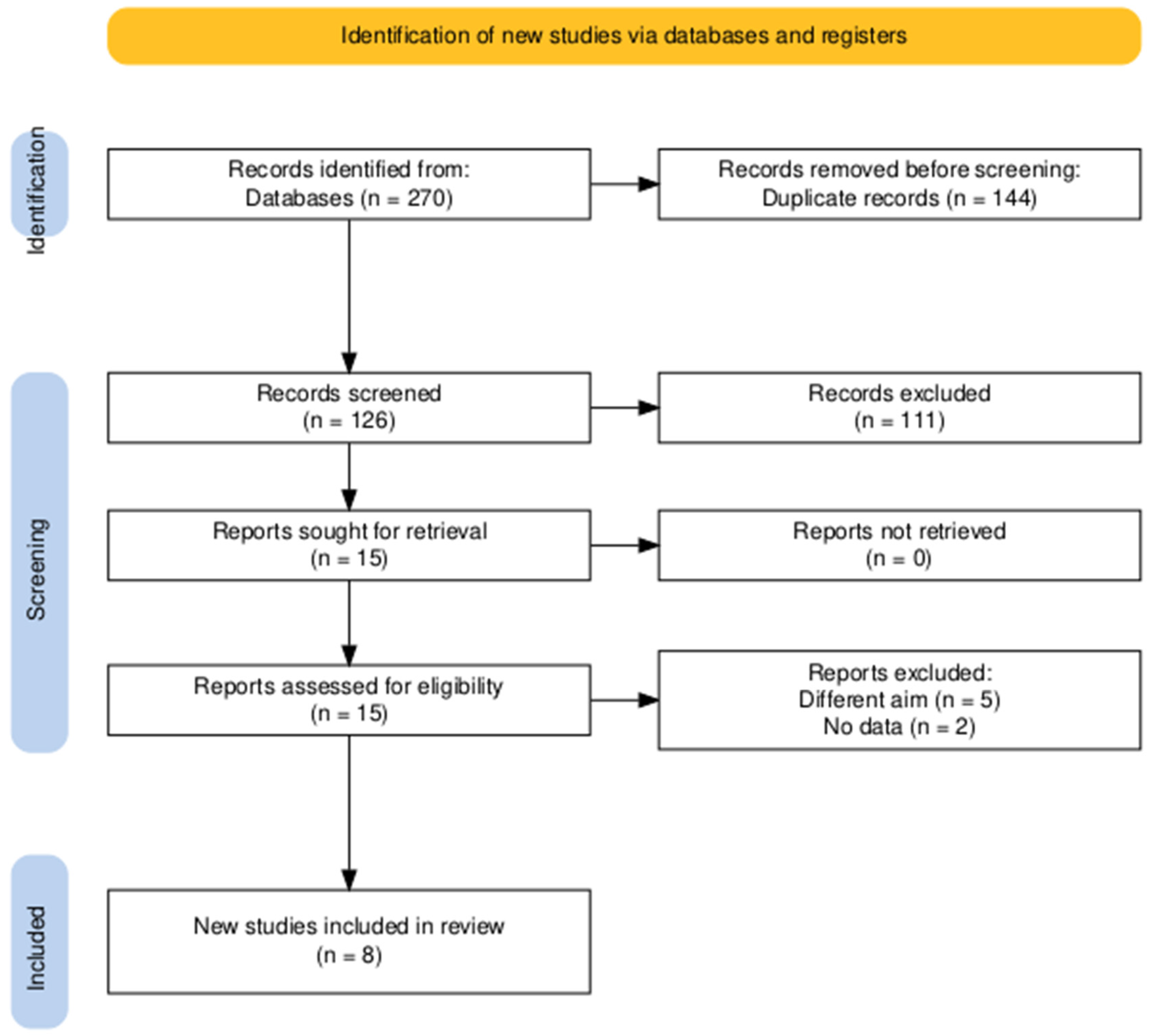

3.1. Searching and Screening

3.2. Characteristics of the Studies

3.3. Quality Assessment and Risk of Bias

3.4. Statistical Analysis

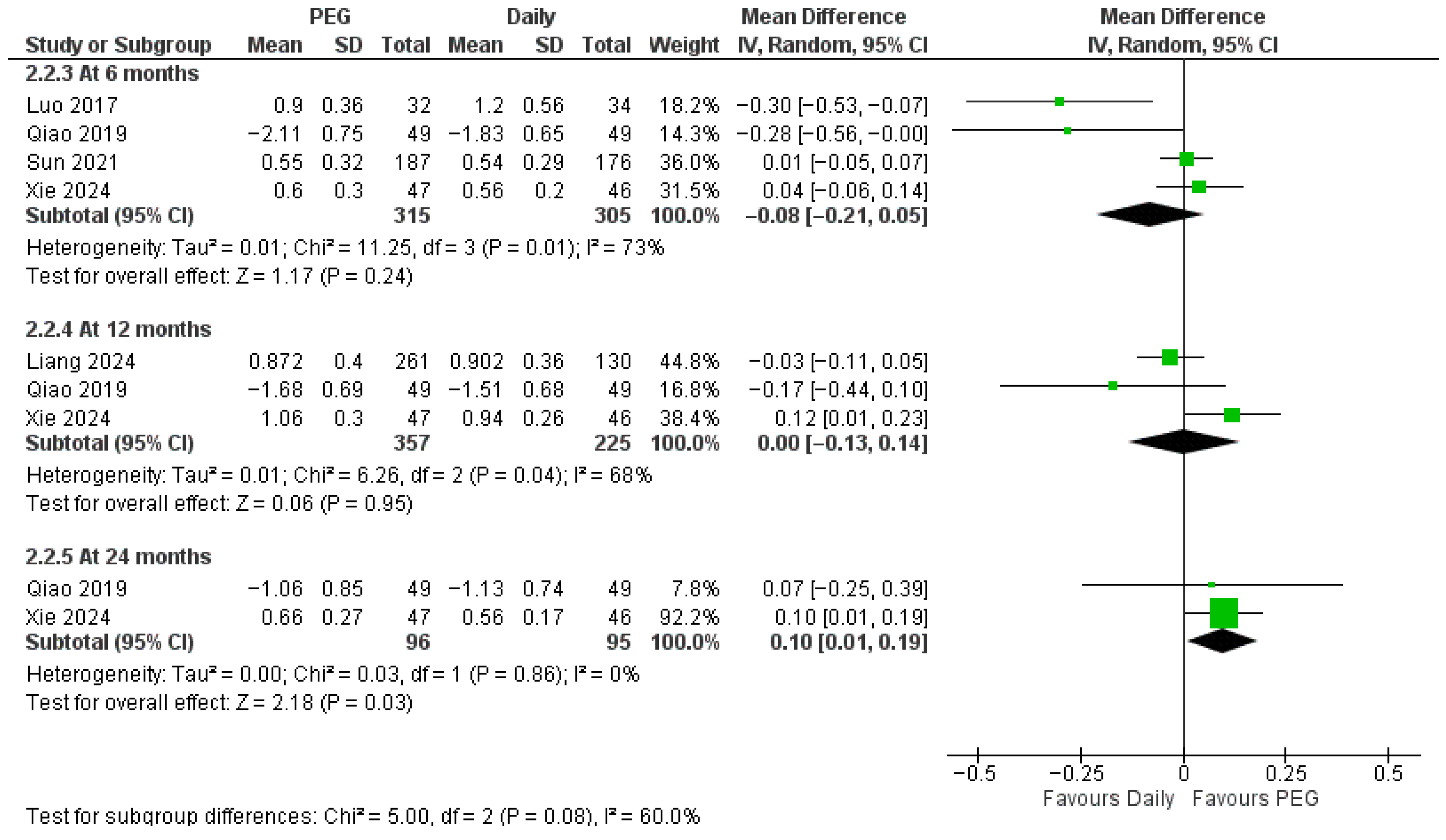

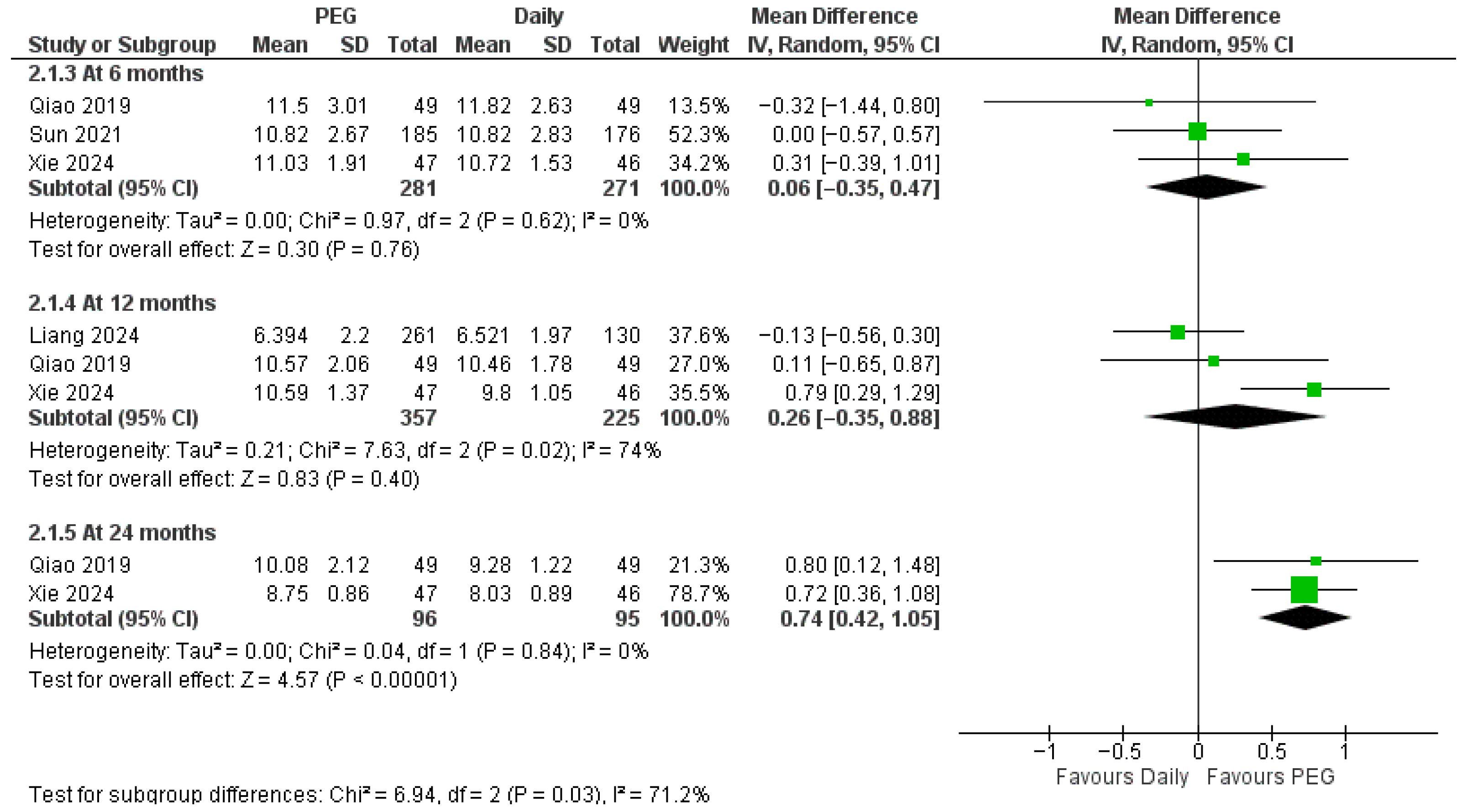

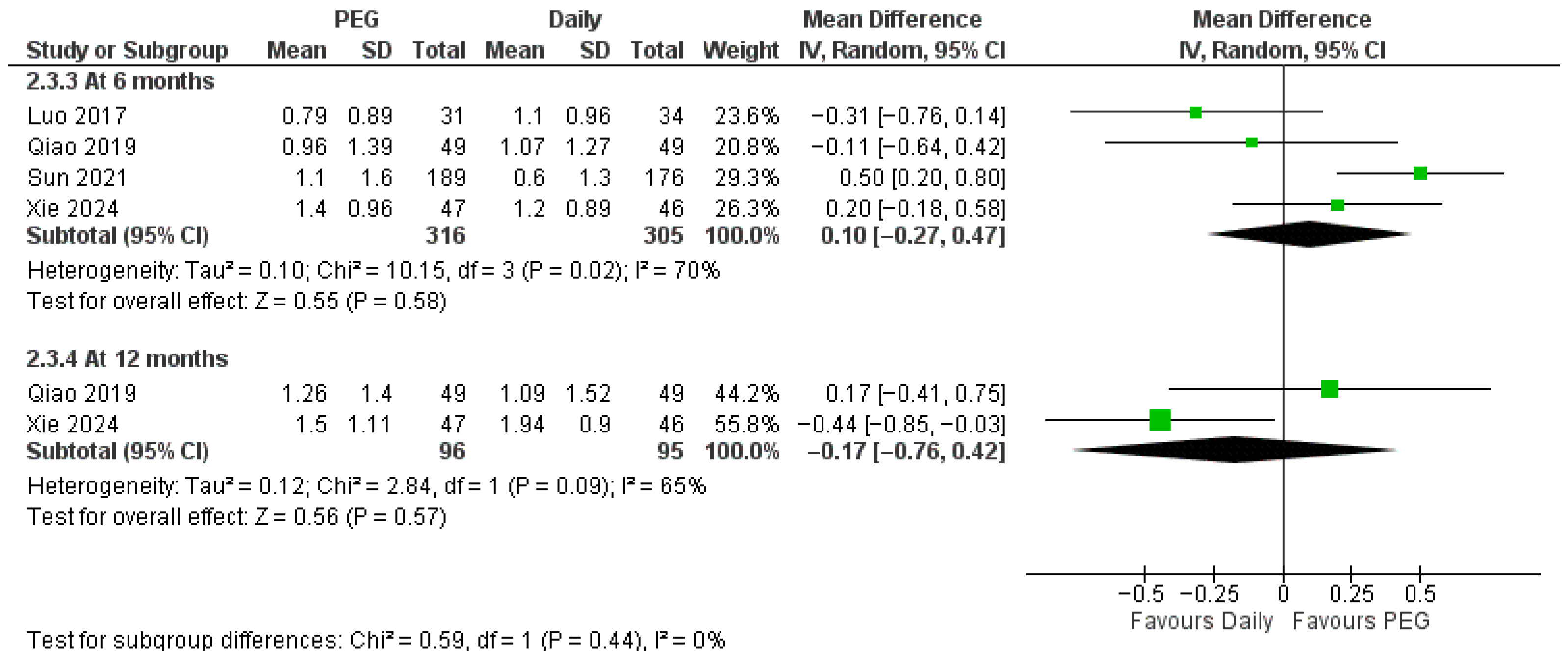

3.4.1. Long-Acting PEG-rhGH vs. Daily GH

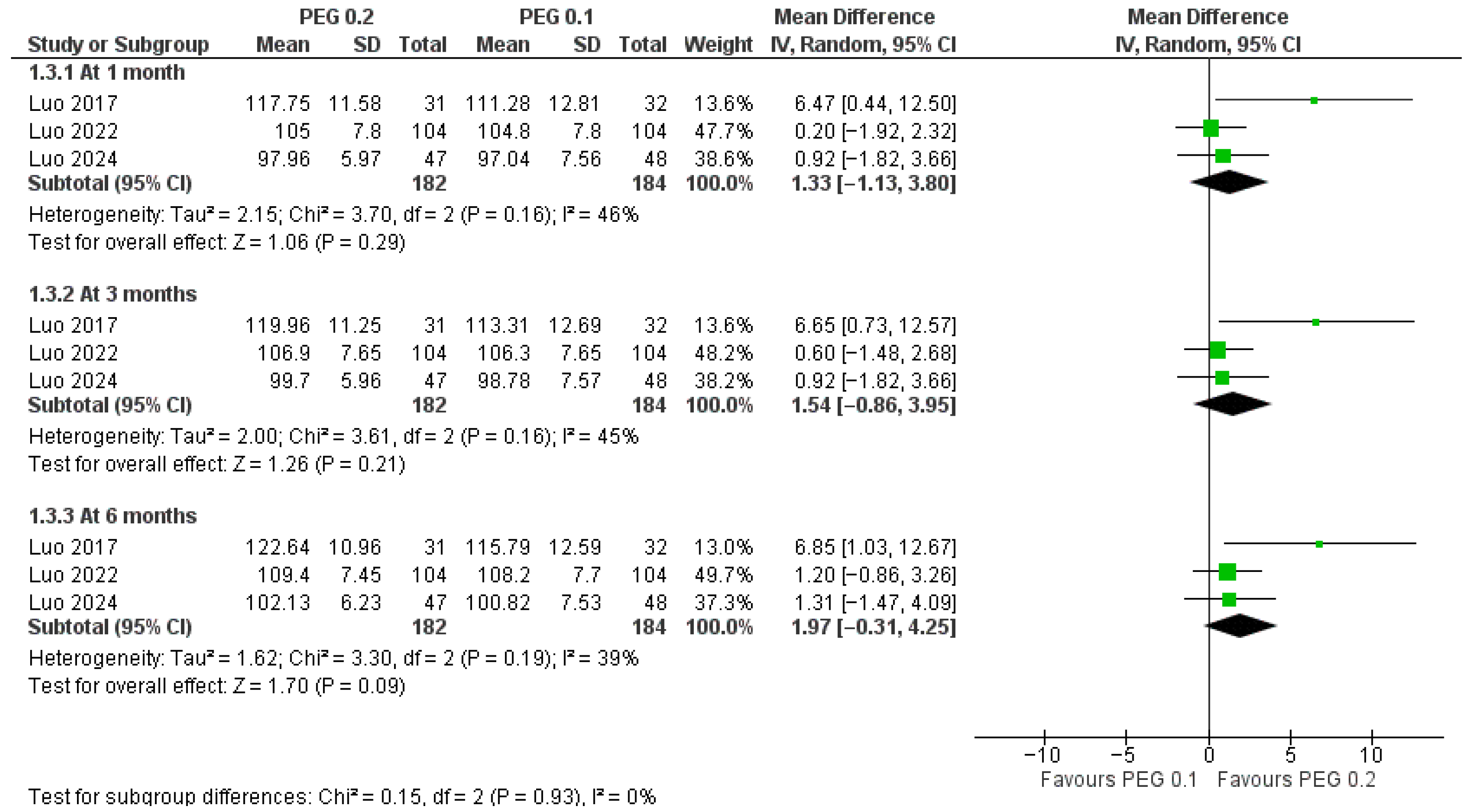

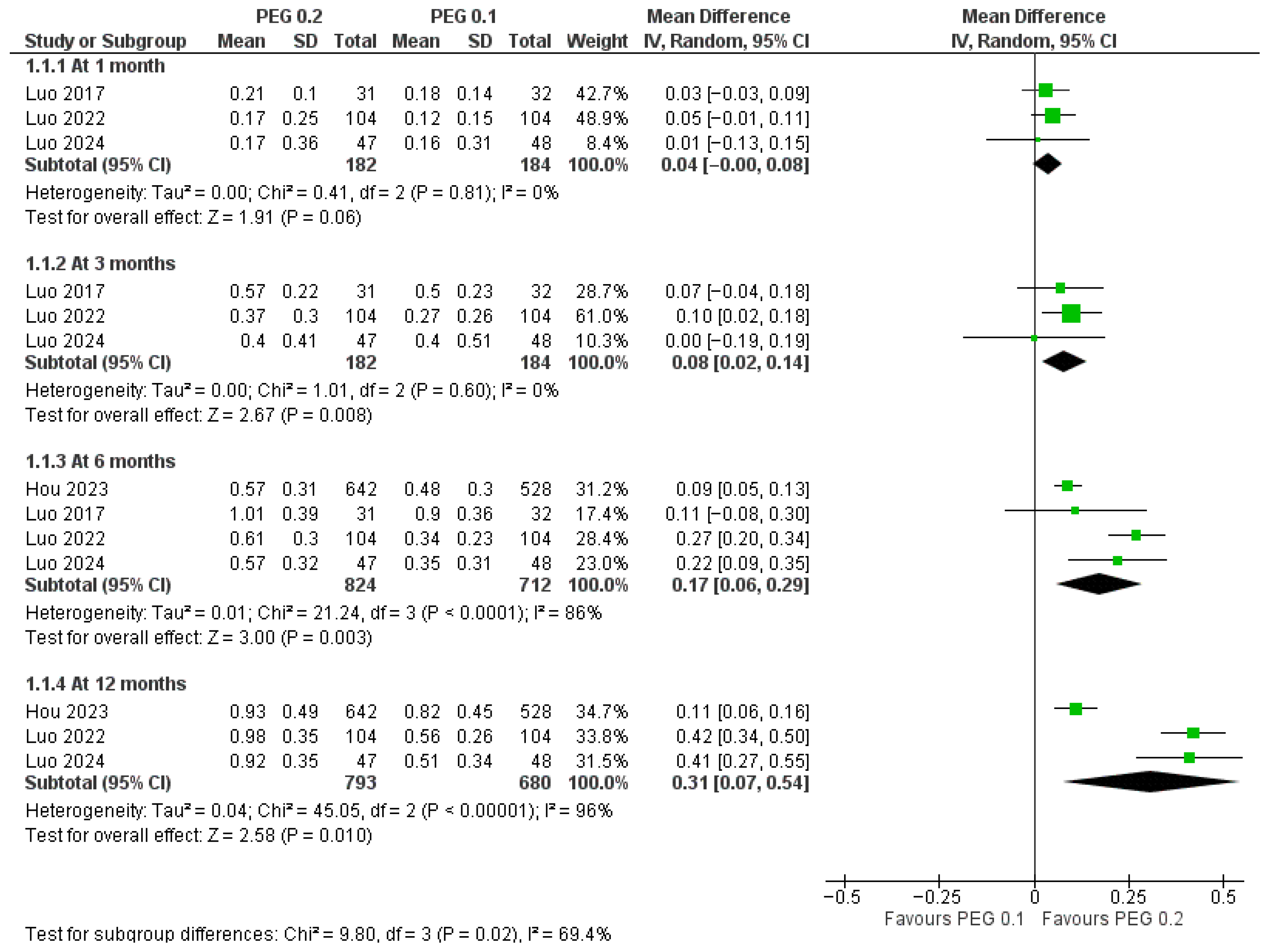

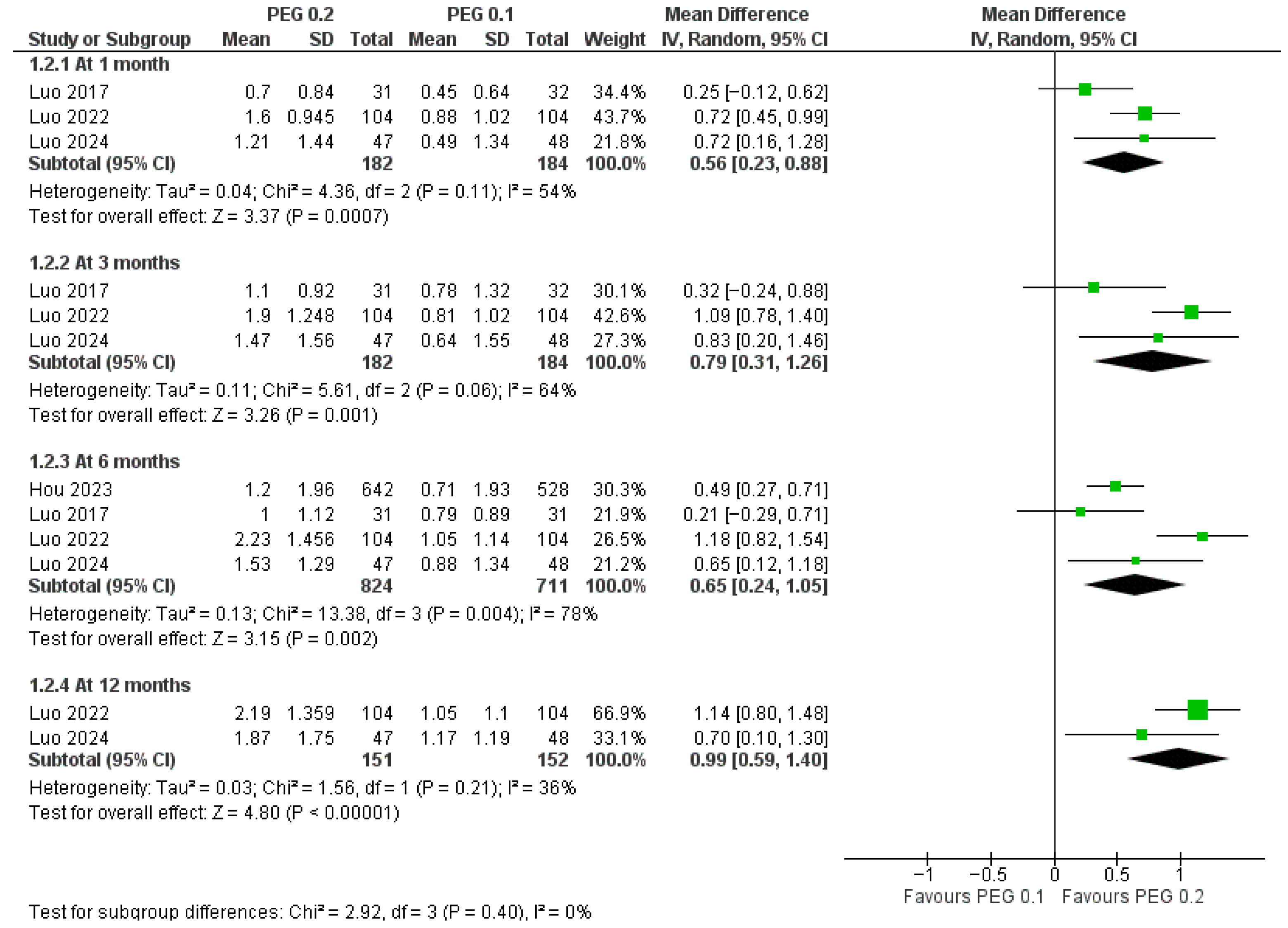

3.4.2. Dose Comparison (PEG-rhGH 0.2 vs. 0.1 mg/kg/week)

4. Discussion

4.1. Summary of Findings

4.2. Investigation with Prior Literature

4.3. Clinical Implications

4.4. Strengths and Limitations

4.5. Recommendations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Grimberg, A.; DiVall, S.A.; Polychronakos, C.; Allen, D.B.; Cohen, L.E.; Quintos, J.B.; Rossi, W.C.; Feudtner, C.; Murad, M.H. Guidelines for Growth Hormone and Insulin-Like Growth Factor-I Treatment in Children and Adolescents: Growth Hormone Deficiency, Idiopathic Short Stature, and Primary Insulin-Like Growth Factor-I Deficiency. Horm. Res. Paediatr. 2016, 86, 361–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanley, T. Diagnosis of growth hormone deficiency in childhood. Curr. Opin. Endocrinol. Diabetes Obes. 2012, 19, 47–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radovick, S.; DiVall, S. Approach to the growth hormone-deficient child during transition to adulthood. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2007, 92, 1195–1200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wit, J.M.; Clayton, P.; Rogol, A.; Savage, M.; Saenger, P.; Cohen, P. Idiopathic short stature: Definition, epidemiology, and diagnostic evaluation. Growth Horm. IGF Res. 2008, 18, 89–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andrade, N.L.; Cellin, L.P.; Rezende, R.C.; Vasques, G.A.; Jorge, A.A. Idiopathic Short Stature: What to Expect from Genomic Investigations. Endocrines 2023, 4, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krysiak, R.; Gdula-Dymek, A.; Bednarska-Czerwińska, A.; Okopień, B. Growth hormone therapy in children and adults. Pharmacol. Rep. 2007, 59, 500–516. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Fisher, B.G.; Acerini, C.L. Understanding the growth hormone therapy adherence paradigm: A systematic review. Horm. Res. Paediatr. 2013, 79, 189–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wit, J.M.; Deeb, A.; Bin-Abbas, B.; Al Mutair, A.; Koledova, E.; Savage, M.O. Achieving Optimal Short- and Long-term Responses to Paediatric Growth Hormone Therapy. J. Clin. Res. Pediatr. Endocrinol. 2019, 11, 329–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sodero, G.; Arzilli, F.; Malavolta, E.; Lezzi, M.; Comes, F.; Villirillo, A.; Rigante, D.; Cipolla, C. Efficacy and Safety of Growth Hormone (GH) Therapy in Patients with SHOX Gene Variants. Children 2025, 12, 325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapoor, R.R.; Burke, S.A.; Sparrow, S.E.; Hughes, I.A.; Dunger, D.B.; Ong, K.K.; Acerini, C.L. Monitoring of concordance in growth hormone therapy. Arch. Dis. Child. 2008, 93, 147–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, B.S.; Velazquez, E.; Yuen, K.C.J. Long-Acting Growth Hormone Preparations—Current Status and Future Considerations. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2020, 105, e2121–e2133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lal, R.A.; Hoffman, A.R. Long-Acting Growth Hormone Preparations in the Treatment of Children. Pediatr. Endocrinol. Rev. 2018, 16, 162–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, L.; Huang, K.; Gong, C.; Luo, F.; Wei, H.; Liang, L.; Du, H.; Zhang, J.; Zhong, Y.; Chen, R.; et al. Long-term Pegylated GH for Children with GH Deficiency: A Large, Prospective, Real-world Study. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2023, 108, 2078–2086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, L.; Lin, S.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, L.; Ou, H.; Huang, S.; Dai, H.; Meng, Z.; Liang, L. Long-term efficacy and safety of PEGylated recombinant human growth hormone in treating Chinese children with growth hormone deficiency: A 5-year retrospective study. J. Pediatr. Endocrinol. Metab. 2024, 37, 892–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuen, K.C.J.; Miller, B.S.; Biller, B.M.K. The current state of long-acting growth hormone preparations for growth hormone therapy. Curr. Opin. Endocrinol. Diabetes Obes. 2018, 25, 267–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouzzani, M.; Hammady, H.; Fedorowicz, Z.; Elmagarmid, A. Rayyan—A web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Syst. Rev. 2016, 5, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sterne, J.A.C.; Savović, J.; Page, M.J.; Elbers, R.G.; Blencowe, N.S.; Boutron, I.; Cates, C.J.; Cheng, H.Y.; Corbett, M.S.; Eldridge, S.M.; et al. RoB 2: A revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ 2019, 366, l4898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stang, A. Critical evaluation of the Newcastle-Ottawa scale for the assessment of the quality of nonrandomized studies in meta-analyses. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 2010, 25, 603–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meca, J.S. Manual del Programa RevMan, Version 5.3; Cochrane Collaboration: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Aydin, O.; Yassikaya, M.Y. Validity and reliability analysis of the PlotDigitizer software program for data extraction from single-case graphs. Perspect. Behav. Sci. 2022, 45, 239–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Y.; Wei, H.; Yang, F.; Zhang, H.; Chen, L.; Yao, H.; Luo, X.; Cheng, X.; Yang, Y.; Lian, Q.; et al. A Novel Y-Shaped Pegylated Recombinant Human Growth Hormone for Children with Growth Hormone Deficiency. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2024, 110, e2605–e2613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, X.; Hou, L.; Liang, L.; Dong, G.; Shen, S.; Zhao, Z.; Gong, C.X.; Li, Y.; Du, M.L.; Su, Z.; et al. Long-acting PEGylated recombinant human growth hormone (Jintrolong) for children with growth hormone deficiency: Phase II and phase III multicenter, randomized studies. Eur. J. Endocrinol. 2017, 177, 195–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, X.; Zhao, S.; Yang, Y.; Dong, G.; Chen, L.; Li, P.; Luo, F.; Gong, C.; Xu, Z.; Xu, X.; et al. Long-acting PEGylated growth hormone in children with idiopathic short stature. Eur. J. Endocrinol. 2022, 187, 709–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, X.; Hou, L.; Zhong, Y.; Zhao, S.; Chen, X.; Dong, Q.; Du, H.; Lu, H.; Yang, Y.; Wu, X.; et al. A Phase 2 Study of PEGylated Recombinant Human Growth Hormone for 52 Weeks in Short Children Born Small for Gestational Age in China. Clin. Endocrinol. 2024, 102, 136–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, Y.; Wang, Z.; Han, J.; Li, G. Use of PEGylated Recombinant Human Growth Hormone in Chinese Children with Growth Hormone Deficiency: A 24-Month Follow-Up Study. Int. J. Endocrinol. 2019, 2019, 1438723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, C.; Lu, B.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Wei, H.; Hu, X.; Hu, P.; Zhao, Q.; Liu, Y.; Ye, K.; et al. Corrigendum: Reduced Effectiveness and Comparable Safety in Biweekly vs. Weekly PEGylated Recombinant Human Growth Hormone for Children With Growth Hormone Deficiency: A Phase IV Non-Inferiority Threshold Targeted Trial. Front. Endocrinol. 2021, 12, 830469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, L.; Li, Y.; Zhang, J.; Guo, S.; Chen, Q.; Ma, H.; Jiang, W. Effect of long-acting PEGylated growth hormone for catch-up growth in children with idiopathic short stature: A 2-year real-world retrospective cohort study. Eur. J. Pediatr. 2024, 183, 4531–4539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, B.S. What do we do now that the long-acting growth hormone is here? Front. Endocrinol. 2022, 13, 980979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.; Chen, J.; Cao, B.; Dou, X.; Peng, Y.; Su, C.; Qin, M.; Wei, L.; Fan, L.; Zhang, B.; et al. First Clinical Study on Long-Acting Growth Hormone Therapy in Children with Turner Sydrome. Horm. Metab. Res. 2022, 54, 389–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maniatis, A.; Cutfield, W.; Dattani, M.; Deal, C.; Collett-Solberg, P.F.; Horikawa, R.; Maghnie, M.; Miller, B.S.; Polak, M.; Sävendahl, L.; et al. Long-Acting Growth Hormone Therapy in Pediatric Growth Hormone Deficiency: A Consensus Statement. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2025, 110, e1232–e1240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mameli, C.; Orso, M.; Calcaterra, V.; Wasniewska, M.G.; Aversa, T.; Granato, S.; Bruschini, P.; Guadagni, L.; d’Angela, D.; Spandonaro, F.; et al. Efficacy, safety, quality of life, adherence and cost-effectiveness of long-acting growth hormone replacement therapy compared to daily growth hormone in children with growth hormone deficiency: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Pharmacol. Res. 2023, 193, 106805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, W.; Luo, X. Long-Term Efficacy and Safety of Growth Hormone in Children Suffering from Short Stature in China (CGLS): An Open-Label, Multicenter, Prospective and Retrospective, Observational Study. Adv. Ther. 2025, 42, 2957–2969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Study ID | Design | Intervention | Control | Sample Size | Chronological Age (Years), Mean (SD) | Male, n (%) | Weight (kg), Mean (SD) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PEG | Control | PEG | Control | PEG | Control | PEG | Control | ||||

| Liang 2024 [22] | RCT | PEG-rhGH 140 μg/kg/week | Daily rhGH 245 μg/kg/week | 261 | 130 | 6.68 (2.11) | 7.03 (2.2) | 172 (65.9) | 87 (66.9) | 18.46 (4.92) | 18.83 (4.75) |

| Luo 2017 (a) [23] | RCT | PEG-rhGH 0.1 mg/kg/week | Daily rhGH 0.25 mg/kg/week | 32 | 34 | 10.91 (3.31) | 10.54 (4.05) | 23 (71.88) | 23 (67.65) | 20.5 (7.23) | 20.18 (6.06) |

| Qiao 2019 [26] | Cohort | PEG-rhGH 0.2 mg/kg/week | Daily rhGH 0.3 mg/kg/week | 49 | 49 | 5.41 (2.37) | 6.25 (2.42) | 26 (53.1) | 33 (67.3) | NR | NR |

| Sun 2021 [27] | RCT | PEG-rhGH 0.20 mg/kg | Daily rhGH 0.25 mg/kg | 187 | 176 | 7.8 (2.8) | 8 (2.9) | 135 (72.2) | 122 (69.5) | 20.7 (7.1) | 20.4 (6.1) |

| Xie 2024 [28] | Cohort | PEG-rhGH 0.2 mg/kg/week | Daily rhGH 0.38 mg/kg/week | 47 | 48 | 6.6 (2.60 | 7.3 (1.8) | 29 (61.7) | 35 (72.9) | NR | NR |

| Hou 2023 [13] | Cohort | PEG-rhGH 0.2 mg/kg/week | PEG-rhGH 0.1 mg/kg/week | 642 | 528 | 7.32 (2.56) | 7.17 (2.54) | 416 (64.8) | 340 (64.39) | 19.4 9(6.10) | 19.4 (6.07) |

| Luo 2017 (b) [23] | RCT | PEG-rhGH 0.2 mg/kg/week | PEG-rhGH 0.1 mg/kg/week | 31 | 32 | 11.75 (3.95) | 10.91 (3.31) | 25 (80.65) | 23 (71.88) | 23.01 (7.01) | 20.5 (7.23) |

| Luo 2022 [24] | RCT | PEG-rhGH 0.2 mg/kg/week | PEG-rhGH 0.1 mg/kg/week | 104 | 104 | 5.3 (1.29) | 5.3 (1.34) | 63 (60.6) | 65 (62.5) | 16.44 (2.93) | 16.37 (2.52) |

| Luo 2024 [25] | RCT | PEG-rhGH 0.2 mg/kg/week | PEG-rhGH 0.1 mg/kg/week | 47 | 48 | 4.3 (0.87) | 4.3 (1.03) | 24 (51.1) | 29 (60.4) | 13.43 (2.02) | 13.18 (2.65) |

| Study ID | Selection (Max 4) | Comparability (Max 2) | Outcome (Max 3) | Total (Max 9) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Qiao 2019 [26] | ☆☆☆☆ | ☆☆ | ☆☆☆ | ☆☆☆☆☆☆☆☆☆ |

| Xie 2024 [28] | ☆☆☆☆ | ☆☆ | ☆☆☆ | ☆☆☆☆☆☆☆☆☆ |

| Hou 2023 [13] | ☆☆☆ | ☆☆ | ☆☆☆ | ☆☆☆☆☆☆☆☆ |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bin-Abbas, B.; Jabari, M.A. Comparative Efficacy and Safety of Once-Weekly Pegylated Recombinant Human Growth Hormone Versus Daily Growth Hormone Therapy in Children: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 8740. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14248740

Bin-Abbas B, Jabari MA. Comparative Efficacy and Safety of Once-Weekly Pegylated Recombinant Human Growth Hormone Versus Daily Growth Hormone Therapy in Children: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(24):8740. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14248740

Chicago/Turabian StyleBin-Abbas, Bassam, and Mosleh Ali Jabari. 2025. "Comparative Efficacy and Safety of Once-Weekly Pegylated Recombinant Human Growth Hormone Versus Daily Growth Hormone Therapy in Children: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 24: 8740. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14248740

APA StyleBin-Abbas, B., & Jabari, M. A. (2025). Comparative Efficacy and Safety of Once-Weekly Pegylated Recombinant Human Growth Hormone Versus Daily Growth Hormone Therapy in Children: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(24), 8740. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14248740