Finerenone: Extending MRAs Prognostic Benefit to the Recently Hospitalized and More Symptomatic Patient with HFpEF

Abstract

1. Introduction

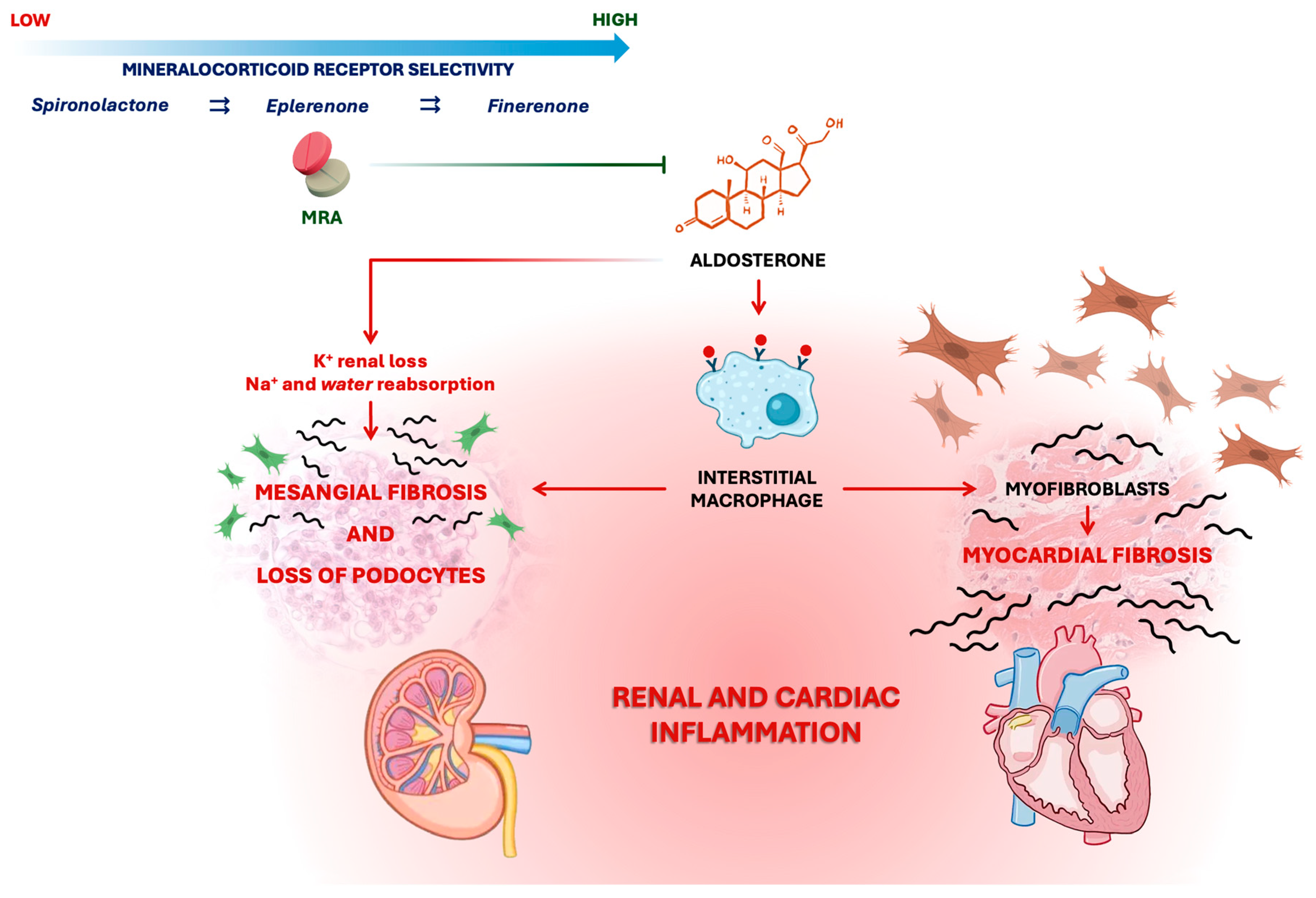

2. The Pathogenic Role of the Mineralocorticoid Receptor and the Rational for Antagonism

2.1. Steroidal MRAs

2.2. Non-Steroidal MRAs

2.3. Mineralocorticoid Receptor Axis Modulation

3. From Subgroup Analyses to a Phenotypic Definition of MRA-Responsive Patients: Lessons Learned from TOPCAT

4. Finerenone and the FINEARTS-HF Trial: From Evidence of Efficacy in Diabetic Nephropathy to Its Role in HFpEF and HFmrEF

5. Clinical Phenotypes and Treatment Response: Insights from FINEARTS-HF Subanalyses

5.1. Impact of Left Ventricular Ejection Fraction

5.2. Impact of Patient Characteristics and Frailty

5.3. Efficacy Across Comorbidities

5.4. Timing, Onset, and Concomitant Therapies

6. Clinical Implications and Limitations

7. Future Directions and Unmet Needs

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- McDonagh, T.A.; Metra, M.; Adamo, M.; Gardner, R.S.; Baumbach, A.; Böhm, M.; Burri, H.; Butler, J.; Čelutkienė, J.; Chioncel, O.; et al. 2021 ESC Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Acute and Chronic Heart Failure: Developed by the Task Force for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Acute and Chronic Heart Failure of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). With the Special Contribution of the Heart Failure Association (HFA) of the ESC. G. Ital. di Cardiol. 2022, 23, e1–e127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonagh, T.A.; Metra, M.; Adamo, M.; Gardner, R.S.; Baumbach, A.; Böhm, M.; Burri, H.; Butler, J.; Čelutkienė, J.; Chioncel, O.; et al. 2023 Focused Update of the 2021 ESC Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Acute and Chronic Heart Failure. Eur. Hear. J. 2023, 44, 3627–3639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pitt, B.; Zannad, F.; Remme, W.J.; Cody, R.; Castaigne, A.; Perez, A.; Palensky, J.; Wittes, J. The Effect of Spironolactone on Morbidity and Mortality in Patients with Severe Heart Failure. N. Engl. J. Med. 1999, 341, 709–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zannad, F.; McMurray, J.J.V.; Krum, H.; van Veldhuisen, D.J.; Swedberg, K.; Shi, H.; Vincent, J.; Pocock, S.J.; Pitt, B.; Group, E.-H.S. Eplerenone in Patients with Systolic Heart Failure and Mild Symptoms. N. Engl. J. Med. 2011, 364, 11–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, K.T. Aldosterone in Congestive Heart Failure. N. Engl. J. Med. 2001, 345, 1689–1697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pitt, B.; Pfeffer, M.A.; Assmann, S.F.; Boineau, R.; Anand, I.S.; Claggett, B.; Clausell, N.; Desai, A.S.; Diaz, R.; Fleg, J.L.; et al. Spironolactone for Heart Failure with Preserved Ejection Fraction. N. Engl. J. Med. 2014, 370, 1383–1392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfeffer, M.A.; Claggett, B.; Assmann, S.F.; Boineau, R.; Anand, I.S.; Clausell, N.; Desai, A.S.; Diaz, R.; Fleg, J.L.; Gordeev, I.; et al. Regional Variation in Patients and Outcomes in the Treatment of Preserved Cardiac Function Heart Failure with an Aldosterone Antagonist (TOPCAT) Trial. Circulation 2015, 131, 34–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bakris, G.L.; Agarwal, R.; Anker, S.D.; Pitt, B.; Ruilope, L.M.; Rossing, P.; Kolkhof, P.; Nowack, C.; Schloemer, P.; Joseph, A.; et al. Effect of Finerenone on Chronic Kidney Disease Outcomes in Type 2 Diabetes. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 383, 2219–2229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pitt, B.; Filippatos, G.; Agarwal, R.; Anker, S.D.; Bakris, G.L.; Rossing, P.; Joseph, A.; Kolkhof, P.; Nowack, C.; Schloemer, P.; et al. Cardiovascular Events with Finerenone in Kidney Disease and Type 2 Diabetes. N. Engl. J. Med. 2021, 385, 2252–2263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vaduganathan, M.; Claggett, B.L.; Lam, C.S.P.; Pitt, B.; Senni, M.; Shah, S.J.; Voors, A.A.; Zannad, F.; Desai, A.S.; Jhund, P.S.; et al. Finerenone in Patients with Heart Failure with Mildly Reduced or Preserved Ejection Fraction: Rationale and Design of the FINEARTS-HF Trial. Eur. J. Hear. Fail. 2024, 26, 1324–1333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Solomon, S.D.; McMurray, J.J.V.; Vaduganathan, M.; Claggett, B.; Jhund, P.S.; Desai, A.S.; Henderson, A.D.; Lam, C.S.P.; Pitt, B.; Senni, M.; et al. Finerenone in Heart Failure with Mildly Reduced or Preserved Ejection Fraction. N. Engl. J. Med. 2024, 391, 1475–1485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, J.P.; Pitt, B.; Zannad, F. Mineralocorticoid Receptor Antagonists in Heart Failure: An Update. Circ. Hear. Fail. 2024, 17, e011629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolkhof, P.; Delbeck, M.; Kretschmer, A.; Steinke, W.; Hartmann, E.; Bärfacker, L.; Eitner, F.; Albrecht-Küpper, B.; Schäfer, S. Finerenone, a Novel Selective Nonsteroidal Mineralocorticoid Receptor Antagonist Protects from Rat Cardiorenal Injury. J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacol. 2014, 64, 69–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zannad, F.; Alla, F.; Dousset, B.; Perez, A.; Pitt, B. Limitation of Excessive Extracellular Matrix Turnover May Contribute to Survival Benefit of Spironolactone Therapy in Patients with Congestive Heart Failure. Circulation 2000, 102, 2700–2706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stienen, S.; Ferreira, J.P.; Pitt, B.; Cleland, J.G.; Pellicori, P.; Girerd, N.; Rossignol, P.; Zannad, F. Eplerenone Prevents an Increase in Serum Carboxy-terminal Propeptide of Procollagen Type I after Myocardial Infarction Complicated by Left Ventricular Dysfunction and/or Heart Failure. Eur. J. Hear. Fail. 2020, 22, 901–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, J.P.; Cleland, J.G.; Girerd, N.; Rossignol, P.; Pellicori, P.; Cosmi, F.; Mariottoni, B.; González, A.; Diez, J.; Solomon, S.D.; et al. Spironolactone Effect on Circulating Procollagen Type I Carboxy-Terminal Propeptide: Pooled Analysis of Three Randomized Trials. Int. J. Cardiol. 2023, 377, 86–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferreira, J.P.; Rossignol, P.; Pizard, A.; Machu, J.-L.; Collier, T.; Girerd, N.; Huby, A.-C.; Gonzalez, A.; Diez, J.; López, B.; et al. Potential Spironolactone Effects on Collagen Metabolism Biomarkers in Patients with Uncontrolled Blood Pressure. Heart 2019, 105, 307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, R.; Kolkhof, P.; Bakris, G.; Bauersachs, J.; Haller, H.; Wada, T.; Zannad, F. Steroidal and Non-Steroidal Mineralocorticoid Receptor Antagonists in Cardiorenal Medicine. Eur. Hear. J. 2020, 42, 152–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sica, D.A. Pharmacokinetics and Pharmacodynamics of Mineralocorticoid Blocking Agents and Their Effects on Potassium Homeostasis. Hear. Fail. Rev. 2005, 10, 23–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seferovic, P.M.; Pelliccia, F.; Zivkovic, I.; Ristic, A.; Lalic, N.; Seferovic, J.; Simeunovic, D.; Milinkovic, I.; Rosano, G. Mineralocorticoid Receptor Antagonists, a Class beyond Spironolactone—Focus on the Special Pharmacologic Properties of Eplerenone. Int. J. Cardiol. 2015, 200, 3–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georgianos, P.I.; Agarwal, R. Mineralocorticoid Receptor Antagonism in Chronic Kidney Disease. Kidney Int. Rep. 2021, 6, 2281–2291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greene, S.J.; Fonarow, G.C.; DeVore, A.D.; Sharma, P.P.; Vaduganathan, M.; Albert, N.M.; Duffy, C.I.; Hill, C.L.; McCague, K.; Patterson, J.H.; et al. Titration of Medical Therapy for Heart Failure with Reduced Ejection Fraction. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2019, 73, 2365–2383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greene, S.J.; Tan, X.; Yeh, Y.-C.; Bernauer, M.; Zaidi, O.; Yang, M.; Butler, J. Factors Associated with Non-Use and Sub-Target Dosing of Medical Therapy for Heart Failure with Reduced Ejection Fraction. Hear. Fail. Rev. 2022, 27, 741–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lullo, L.D.; Lavalle, C.; Scatena, A.; Mariani, M.V.; Ronco, C.; Bellasi, A. Finerenone: Questions and Answers—The Four Fundamental Arguments on the New-Born Promising Non-Steroidal Mineralocorticoid Receptor Antagonist. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 3992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harrington, J.L.; Canonico, M.E.; Rafei, A.E.; Solomon, S.D.; Teerlink, J.R.; Vaduganathan, M.; Zieroth, S.R.; Bonaca, M.P.; Sauer, A.J. Nonsteroidal and Steroidal Mineralocorticoid Antagonists Rationale, Evidence, and Unanswered Questions. JACC Hear. Fail. 2025, 13, 102637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mark, P.B.; Sousa-Amorim, E.D.; Eriksson, A.L.; Leonsson-Zachrisson, M.; Guzman, N.J.; Miller, M.T.; Jiang, Y.; Heerspink, H.J.L. Efficacy and Safety of Balcinrenone and Dapagliflozin for CKD: Design and Baseline Characteristics of the MIRO-CKD Trial. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2025, 40, 2280–2288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lam, C.S.P.; Køber, L.; Kuwahara, K.; Lund, L.H.; Mark, P.B.; Mellbin, L.G.; Schou, M.; Pizzato, P.E.; Gabrielsen, A.; Gasparyan, S.B.; et al. Balcinrenone plus Dapagliflozin in Patients with Heart Failure and Chronic Kidney Disease: Results from the Phase 2b MIRACLE Trial. Eur. J. Hear. Fail. 2024, 26, 1727–1735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, S.K.; Teoh, H.; Saunthar, A.; Yau, T.M.; Verma, S. The Emerging Role of Aldosterone Synthase Inhibitors in Overcoming Renin–Angiotensin–Aldosterone System Therapy Limitations: A Narrative Review. Card. Fail. Rev. 2025, 11, e20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfeffer, M.A.; Claggett, B. Behind the Scenes of TOPCAT—Bending to Inform. NEJM Évid. 2022, 1, EVIDctcs2100007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maggioni, A.P. Multination Clinical Trials: What Is the Relevance and What Are the Lessons from across-Country Differences? G. Ital. di Cardiol. 2014, 15, 221–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Denus, S.; O’meara, E.; Desai, A.S.; Claggett, B.; Lewis, E.F.; Leclair, G.; Jutras, M.; Lavoie, J.; Solomon, S.D.; Pitt, B.; et al. Spironolactone Metabolites in TOPCAT—New Insights into Regional Variation. N. Engl. J. Med. 2017, 376, 1690–1692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heidenreich, P.A.; Bozkurt, B.; Aguilar, D.; Allen, L.A.; Byun, J.J.; Colvin, M.M.; Deswal, A.; Drazner, M.H.; Dunlay, S.M.; Evers, L.R.; et al. 2022 AHA/ACC/HFSA Guideline for the Management of Heart Failure: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation 2022, 145, e895–e1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solomon, S.D.; Claggett, B.; Lewis, E.F.; Desai, A.; Anand, I.; Sweitzer, N.K.; O’Meara, E.; Shah, S.J.; McKinlay, S.; Fleg, J.L.; et al. Influence of Ejection Fraction on Outcomes and Efficacy of Spironolactone in Patients with Heart Failure with Preserved Ejection Fraction. Eur. Hear. J. 2016, 37, 455–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Merrill, M.; Sweitzer, N.K.; Lindenfeld, J.; Kao, D.P. Sex Differences in Outcomes and Responses to Spironolactone in Heart Failure with Preserved Ejection Fraction a Secondary Analysis of TOPCAT Trial. JACC Hear. Fail. 2019, 7, 228–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Addetia, K.; Miyoshi, T.; Amuthan, V.; Citro, R.; Daimon, M.; Fajardo, P.G.; Kasliwal, R.R.; Kirkpatrick, J.N.; Monaghan, M.J.; Muraru, D.; et al. Normal Values of Left Ventricular Size and Function on Three-Dimensional Echocardiography: Results of the World Alliance Societies of Echocardiography Study. J. Am. Soc. Echocardiogr. 2022, 35, 449–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beldhuis, I.E.; Myhre, P.L.; Claggett, B.; Damman, K.; Fang, J.C.; Lewis, E.F.; O’Meara, E.; Pitt, B.; Shah, S.J.; Voors, A.A.; et al. Efficacy and Safety of Spironolactone in Patients with HFpEF and Chronic Kidney Disease. JACC Hear. Fail. 2019, 7, 25–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beldhuis, I.E.; Myhre, P.L.; Bristow, M.; Claggett, B.; Damman, K.; Fang, J.C.; Fleg, J.L.; McKinlay, S.; Lewis, E.F.; O’Meara, E.; et al. Spironolactone in Patients with Heart Failure, Preserved Ejection Fraction, and Worsening Renal Function. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2021, 77, 1211–1221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vardeny, O.; Claggett, B.; Vaduganathan, M.; Beldhuis, I.; Rouleau, J.; O’Meara, E.; Anand, I.S.; Shah, S.J.; Sweitzer, N.K.; Fang, J.C.; et al. Influence of Age on Efficacy and Safety of Spironolactone in Heart Failure. JACC Hear. Fail. 2019, 7, 1022–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J.B.; Schrauben, S.J.; Zhao, L.; Basso, M.D.; Cvijic, M.E.; Li, Z.; Yarde, M.; Wang, Z.; Bhattacharya, P.T.; Chirinos, D.A.; et al. Clinical Phenogroups in Heart Failure with Preserved Ejection Fraction Detailed Phenotypes, Prognosis, and Response to Spironolactone. JACC Hear. Fail. 2020, 8, 172–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agarwal, R.; Filippatos, G.; Pitt, B.; Anker, S.D.; Rossing, P.; Joseph, A.; Kolkhof, P.; Nowack, C.; Gebel, M.; Ruilope, L.M.; et al. Cardiovascular and Kidney Outcomes with Finerenone in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes and Chronic Kidney Disease: The FIDELITY Pooled Analysis. Eur. Hear. J. 2021, 43, 474–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solomon, S.D.; Ostrominski, J.W.; Vaduganathan, M.; Claggett, B.; Jhund, P.S.; Desai, A.S.; Lam, C.S.P.; Pitt, B.; Senni, M.; Shah, S.J.; et al. Baseline Characteristics of Patients with Heart Failure with Mildly Reduced or Preserved Ejection Fraction: The FINEARTS-HF Trial. Eur. J. Hear. Fail. 2024, 26, 1334–1346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostrominski, J.W.; Aggarwal, R.; Claggett, B.L.; Kulac, I.J.; Desai, A.S.; Jhund, P.S.; Lam, C.S.P.; Pitt, B.; Senni, M.; Shah, S.J.; et al. Generalizability of the Spectrum of Kidney Risk in the FINEARTS-HF Trial to U.S. Adults with Heart Failure. J. Card. Fail. 2024, 30, 1170–1174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anker, S.D.; Butler, J.; Filippatos, G.; Ferreira, J.P.; Bocchi, E.; Böhm, M.; Brunner–La Rocca, H.-P.; Choi, D.-J.; Chopra, V.; Chuquiure-Valenzuela, E.; et al. Empagliflozin in Heart Failure with a Preserved Ejection Fraction. N. Engl. J. Med. 2021, 385, 1451–1461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Solomon, S.D.; McMurray, J.J.V.; Claggett, B.; de Boer, R.A.; DeMets, D.; Hernandez, A.F.; Inzucchi, S.E.; Kosiborod, M.N.; Lam, C.S.P.; Martinez, F.; et al. Dapagliflozin in Heart Failure with Mildly Reduced or Preserved Ejection Fraction. N. Engl. J. Med. 2022, 387, 1089–1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Causland, F.R.M.; Vaduganathan, M.; Claggett, B.L.; Kulac, I.J.; Desai, A.S.; Jhund, P.S.; Henderson, A.D.; Brinker, M.; Perkins, R.; Scheerer, M.F.; et al. Finerenone and Kidney Outcomes in Patients with Heart Failure The FINEARTS-HF Trial. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2025, 85, 159–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaduganathan, M.; Claggett, B.L.; Desai, A.S.; Jhund, P.S.; Lam, C.S.P.; Senni, M.; Shah, S.J.; Voors, A.A.; Zannad, F.; Pitt, B.; et al. Estimated Long-Term Benefits of Finerenone in Heart Failure. JAMA Cardiol. 2025, 10, 176–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Docherty, K.F.; Henderson, A.D.; Jhund, P.S.; Claggett, B.L.; Desai, A.S.; Mueller, K.; Viswanathan, P.; Scalise, A.; Lam, C.S.P.; Senni, M.; et al. Efficacy and Safety of Finerenone Across the Ejection Fraction Spectrum in Heart Failure With Mildly Reduced or Preserved Ejection Fraction: A Prespecified Analysis of the FINEARTS-HF Trial. Circulation 2025, 151, 45–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cunningham, J.W.; Claggett, B.L.; Vaduganathan, M.; Desai, A.S.; Jhund, P.S.; Lam, C.S.P.; Senni, M.; Shah, S.; Voors, A.; Zannad, F.; et al. Effects of Finerenone on Natriuretic Peptide Levels in Heart Failure with Mildly Reduced or Preserved Ejection Fraction: The FINEARTS-HF Trial. Eur. J. Hear. Fail. 2025, 27, 1487–1491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anand, I.S.; Claggett, B.; Liu, J.; Shah, A.M.; Rector, T.S.; Shah, S.J.; Desai, A.S.; O’Meara, E.; Fleg, J.L.; Pfeffer, M.A.; et al. Interaction Between Spironolactone and Natriuretic Peptides in Patients with Heart Failure and Preserved Ejection Fraction from the TOPCAT Trial. JACC Hear. Fail. 2017, 5, 241–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vardeny, O.; Fang, J.C.; Desai, A.S.; Jhund, P.S.; Claggett, B.; Vaduganathan, M.; de Boer, R.A.; Hernandez, A.F.; Lam, C.S.P.; Inzucchi, S.E.; et al. Dapagliflozin in Heart Failure with Improved Ejection Fraction: A Prespecified Analysis of the Deliver Trial. Nat. Med. 2022, 28, 2504–2511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pabon, M.A.; Vardeny, O.; Vaduganathan, M.; Desai, A.S.; Claggett, B.L.; Kulac, I.J.; Jhund, P.S.; Lam, C.S.P.; Senni, M.; Shah, S.J.; et al. Finerenone in Heart Failure with Improved Ejection Fraction. JAMA Cardiol. 2025, 10, 740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halliday, B.P.; Wassall, R.; Lota, A.S.; Khalique, Z.; Gregson, J.; Newsome, S.; Jackson, R.; Rahneva, T.; Wage, R.; Smith, G.; et al. Withdrawal of Pharmacological Treatment for Heart Failure in Patients with Recovered Dilated Cardiomyopathy (TRED-HF): An Open-Label, Pilot, Randomised Trial. Lancet 2019, 393, 61–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chimura, M.; Wang, X.; Jhund, P.S.; Henderson, A.D.; Claggett, B.L.; Desai, A.S.; Fonseca, C.; Goncalvesova, E.; Katova, T.; Mueller, K.; et al. Finerenone in Women and Men with Heart Failure with Mildly Reduced or Preserved Ejection Fraction. JAMA Cardiol. 2025, 10, 59–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chimura, M.; Petrie, M.C.; Schou, M.; Martinez, F.A.; Henderson, A.D.; Claggett, B.L.; Desai, A.S.; Kolkhof, P.; Viswanathan, P.; Lage, A.; et al. Finerenone Improves Outcomes in Patients with Heart Failure with Mildly Reduced or Preserved Ejection Fraction Irrespective of Age: A Prespecified Analysis of FINEARTS-HF. Circ. Hear. Fail. 2024, 17, e012437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Butt, J.H.; Jhund, P.S.; Henderson, A.D.; Claggett, B.L.; Chiang, C.-E.; Linssen, G.C.M.; Saldarriaga, C.I.; Saraiva, J.F.K.; Sato, N.; Schou, M.; et al. Finerenone According to Frailty in Heart Failure. JAMA Cardiol. 2025, 10, 829–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, M.; Henderson, A.D.; Talebi, A.; Atherton, J.J.; Chiang, C.-E.; Chopra, V.; Comin-Colet, J.; Kosiborod, M.N.; Saraiva, J.F.K.; Claggett, B.L.; et al. Effect of Finerenone on the KCCQ in Patients with HFmrEF/HFpEF A Prespecified Analysis of FINEARTS-HF. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2025, 85, 120–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostrominski, J.W.; Vaduganathan, M.; Claggett, B.L.; Desai, A.S.; Jhund, P.S.; Lam, C.S.P.; Senni, M.; Shah, S.J.; Voors, A.A.; Zannad, F.; et al. Finerenone and New York Heart Association Functional Class in Heart Failure: The FINEARTS-HF Trial. JACC Hear. Fail. 2025; in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Butt, J.H.; Henderson, A.D.; Jhund, P.S.; Claggett, B.L.; Desai, A.S.; Lay-Flurrie, J.; Viswanathan, P.; Lage, A.; Scheerer, M.F.; Lam, C.S.P.; et al. Finerenone, Obesity, and Heart Failure with Mildly Reduced/Preserved Ejection Fraction Prespecified Analysis of FINEARTS-HF. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2025, 85, 140–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakris, G.L.; Ruilope, L.M.; Anker, S.D.; Filippatos, G.; Pitt, B.; Rossing, P.; Fried, L.; Roy-Chaudhury, P.; Sarafidis, P.; Ahlers, C.; et al. A Prespecified Exploratory Analysis from FIDELITY Examined Finerenone Use and Kidney Outcomes in Patients with Chronic Kidney Disease and Type 2 Diabetes. Kidney Int. 2023, 103, 196–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostrominski, J.W.; Causland, F.R.M.; Claggett, B.L.; Desai, A.S.; Jhund, P.S.; Lam, C.S.P.; Senni, M.; Shah, S.J.; Voors, A.A.; Zannad, F.; et al. Finerenone Across the Spectrum of Kidney Risk in Heart Failure: The FINEARTS-HF Trial. JACC Hear. Fail. 2025; Online ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunningham, J.W.; Chatur, S.; Claggett, B.L.; Vaduganathan, M.; Desai, A.S.; Jhund, P.S.; Esperón, G.L.; Lam, C.S.P.; Sato, N.; Senni, M.; et al. Finerenone and Outpatient Worsening Heart Failure with Mildly Reduced or Preserved Ejection Fraction. JAMA Cardiol. 2025, 10, 370–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chimura, M.; Yang, M.; Henderson, A.D.; Jhund, P.S.; Docherty, K.F.; Claggett, B.L.; Desai, A.S.; Filippatos, G.; Gajos, G.; Mueller, K.; et al. Anaemia in Patients with Heart Failure and Mildly Reduced or Preserved Ejection Fraction: A Prespecified Analysis of the FINEARTS-HF Trial. Eur. J. Hear. Fail. 2025; Online ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butt, J.H.; Jhund, P.S.; Henderson, A.D.; Claggett, B.L.; Desai, A.S.; Lam, C.S.P.; Mueller, K.; Scheerer, M.F.; Viswanathan, P.; Senni, M.; et al. Finerenone, Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease, and Heart Failure with Mildly Reduced or Preserved Ejection Fraction: A Prespecified Analysis of the FINEARTS-HF Trial. Eur. J. Hear. Fail. 2025, 27, 1444–1458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramalho, S.H.R.; Claggett, B.L.; Sweitzer, N.K.; Fang, J.C.; Shah, S.J.; Anand, I.S.; Pitt, B.; Lewis, E.F.; Pfeffer, M.A.; Solomon, S.D.; et al. Impact of Pulmonary Disease on the Prognosis in Heart Failure with Preserved Ejection Fraction: The TOPCAT Trial. Eur. J. Hear. Fail. 2020, 22, 557–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Butt, J.H.; Jhund, P.S.; Henderson, A.D.; Claggett, B.L.; Desai, A.S.; Lam, C.S.P.; Brinker, M.; Schloemer, P.; Viswanathan, P.; Lage, A.; et al. Finerenone, Glycaemic Status, and Heart Failure with Mildly Reduced or Preserved Ejection Fraction: A Prespecified Analysis of the FINEARTS-HF Trial. Eur. J. Hear. Fail. 2025, 27, 1326–1341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostrominski, J.W.; Claggett, B.L.; Desai, A.S.; Jhund, P.S.; Lam, C.S.P.; Senni, M.; Shah, S.J.; Voors, A.A.; Zannad, F.; Pitt, B.; et al. Finerenone According to Insulin Resistance in Heart Failure: Insights from the FINEARTS-HF Trial. Eur. J. Hear. Fail. 2025; Online ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaduganathan, M.; Claggett, B.L.; Desai, A.S.; Jhund, P.S.; Lam, C.S.P.; Senni, M.; Shah, S.J.; Voors, A.A.; Zannad, F.; Pitt, B.; et al. Time to Significant Benefit of Finerenone in Patients with Heart Failure. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2025, 85, 199–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desai, A.S.; Vaduganathan, M.; Claggett, B.L.; Kulac, I.J.; Jhund, P.S.; Cunningham, J.; Borentain, M.; Lay-Flurrie, J.; Viswanathan, P.; Rohwedder, K.; et al. Finerenone in Patients with a Recent Worsening Heart Failure Event The FINEARTS-HF Trial. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2025, 85, 106–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaduganathan, M.; Claggett, B.L.; Kulac, I.J.; Miao, Z.M.; Desai, A.S.; Jhund, P.S.; Henderson, A.D.; Brinker, M.; Lay-Flurrie, J.; Viswanathan, P.; et al. Effects of the Nonsteroidal MRA Finerenone With and Without Concomitant SGLT2 Inhibitor Use in Heart Failure. Circulation 2025, 151, 149–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chimura, M.; Jhund, P.S.; Henderson, A.D.; Yang, M.; Claggett, B.L.; Desai, A.S.; Rohwedder, K.; Lage, A.; Scalise, A.; Mueller, K.; et al. Efficacy and Tolerability of Finerenone According to the Use and Dosage of Diuretics. JAMA Cardiol. 2025, 10, 979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matsumoto, S.; Henderson, A.D.; Jhund, P.S.; Bauersachs, J.; Chioncel, O.; Claggett, B.L.; Comin-Colet, J.; Desai, A.S.; Filippatos, G.; Lam, C.S.P.; et al. Finerenone and Atrial Fibrillation in Heart Failure. JAMA Cardiol. 2025, 10, 696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jhund, P.S.; Talebi, A.; Henderson, A.D.; Claggett, B.L.; Vaduganathan, M.; Desai, A.S.; Lam, C.S.P.; Pitt, B.; Senni, M.; Shah, S.J.; et al. Mineralocorticoid Receptor Antagonists in Heart Failure: An Individual Patient Level Meta-Analysis. Lancet 2024, 404, 1119–1131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Author | Focus of Analysis/Target Population/Subgroup | Key Findings & Outcomes | Clinical Implications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Vaduganathan M. et al., 2024 [46] | Projected lifetime effects in total study cohort (N = 6001) | Estimated gain of 3.1 event-free years in 55-year-olds (95% CI 0.8–5.4; p = 0.007) and 2.0 years in 65-year-olds (95% CI 0.8–3.3; p < 0.001) | Early initiation of therapy correlates with maximized cumulative survival benefit, particularly in younger to middle-aged patients |

| Docherty K.F. et al., 2024 [47] | Efficacy stratified by LVEF: <50% vs. 50–60% vs. ≥60%; Patients with available baseline LVEF (N = 5993) | Consistent risk reduction across all strata: RR 0.84 (LVEF < 50%), 0.80 (LVEF 50–60%), 0.94 (LVEF ≥ 60%). No significant interaction (p = 0.70) | Efficacy is preserved regardless of ejection fraction, supporting broad applicability across the HFmrEF/HFpEF continuum |

| Vaduganathan M. et al., 2024 [69] | Efficacy and safety based on concomitant SGLT2i use; Users (N = 817) vs. Non-users (N = 817) of SGLT2i at baseline | Similar magnitude of benefit in patients on SGLT2i (HR 0.83) versus those not on therapy (HR 0.85); p-interaction = 0.76. | Finerenone provides additive benefit on top of standard-of-care SGLT2i therapy without safety signals |

| Chimura M. et al., 2024 [54] | Efficacy by age stratification; age quartiles (Q1 to Q4) | Uniform efficacy across age groups (p-interaction = 0.27). HR ranged from 0.70 in youngest to 0.85 in oldest quartile. | Advanced age does not diminish therapeutic efficacy or increase the rate of adverse events significantly. |

| Vaduganathan M. et al., 2024 [67] | Onset of benefit as time-to-event analysis; total study cohort (N = 6001) | Significant divergence in primary endpoint curves observed by day 28 (HR 0.62; p = 0.037). | Rapid therapeutic onset suggests mechanisms involving hemodynamic load reduction beyond slow anti-fibrotic remodeling. |

| Mc Causland F.R. et al., 2024 [45] | Renal Outcome Analysis; total study cohort (N = 6001) | No significant difference in composite renal endpoints (HR 1.33). Marked reduction in new-onset microalbuminuria (−24%) and macroalbuminuria (−38%). | While not affecting eGFR decline slopes in this low-risk population, the drug offers significant anti-albuminuric protection. |

| Desai A.S. et al., 2024 [68] | Efficacy and safety stratified by time from WHF event; total study cohort (N = 6001) | Trend toward greater relative risk reduction in patients enrolled <7 days post-discharge (HR 0.74) vs. >3 months (HR 0.99). | Initiating therapy in the vulnerable post-discharge phase may yield superior absolute risk reductions. |

| Yang M. et al., 2024 [56] | Efficacy stratified by baseline KCCQ-TSS; baseline KCCQ-TSS available in 5986 patients | Consistent event reduction across symptom tertiles (p-interaction = 0.89). Significant improvement in KCCQ scores at 1 year (+1.6 points; p < 0.001). | Improving quality of life is a distinct benefit, achievable regardless of baseline symptom severity. |

| Chimura M. et al., 2024 [53] | Efficacy and safety by sex; total study cohort (N = 6001); Male vs. Female | Comparable efficacy in women (HR 0.78) and men (HR 0.88); p-interaction = 0.41. Similar safety profile. | Sex does not modulate the therapeutic response, confirming utility in the female-predominant HFpEF population. |

| Matsumoto S. et al., 2025 [71] | Efficacy and safety based on baseline AF status; Paroxysmal 1384 (23.1%) vs. Persistent 1886 (31.5%) vs. No AF | Efficacy maintained across AF subtypes (p-interaction = 0.94). Trend towards reduction in new-onset AF (HR 0.77; p = 0.09). | Investigational signal suggesting potential anti-arrhythmic properties mediated by atrial reverse remodeling |

| Butt JV et al., 2025 [65] | Efficacy safety analysis by Glycemic Status; Diabetes 2764 (46.2%) vs. Pre-diabetes 1979 (33.1%) vs. Normoglycemia 1243 (20.8%) | Consistent benefit across glycemic spectrum (p-interaction = 0.93). HR ranged from 0.82 (diabetes) to 0.85 (normoglycemia) | Cardiovascular protection is independent of diabetic status, expanding indication beyond diabetic kidney disease. |

| Ostrominski, JW et al., 2025 [57] | Efficacy/safety by NYHA class; NYHA II 4146 (69%) vs. III/IV 1854 (31%) | Relative benefit consistent (p = 0.54), but absolute risk reduction more than double in NYHA III/IV (ARR 4.5 vs. 2.0 per 100 py). | Treating more symptomatic patients yields a higher return in terms of absolute events prevented. |

| Cunningham JW et al., 2025 [48] | Influence of baseline NT-proBNP; NT-proBNP available in 5843 patients | Baseline natriuretic peptide levels did not predict or alter the treatment response (p interaction = 0.92). Finerenone significantly lowered NT-proBNP levels by ~12% at both 3 and 12 months | Influence of baseline NT-proBNP; NT-proBNP available in 5843 patients |

| Chimura M et al., 2025 [62] | Effects according to anaemia status; 1584 (28.0%) with baseline anaemia | Clinical efficacy was not hindered by the presence of anaemia (RR 0.89 in anaemic vs. 0.76 in non-anaemic patients; p interaction = 0.27) | Mean haemoglobin levels showed a slight, non-clinical decrease (−0.12 g/dL) in the treatment arm compared to placebo |

| Pabon MA et al., 2025 [51] | Efficacy/safety in participants with HFimpEF; 273 (5%) patients with a history of LVEF < 40% | Efficacy in HFimpEF (HR consistent with main cohort, p-interaction = 0.36). Higher absolute risk reduction (9.2 events per 100 py). | Patients with recovered EF remain at high risk and derive substantial benefit from continued neurohormonal blockade |

| Butt JH et al., 2025 [63] | Effects according to COPD status/773 (12.9%) with COPD | risk reduction was identical in patients with and without COPD (RR 0.84; p interaction = 0.93) | Comorbid COPD did not modify the efficacy or safety outcomes of finerenone |

| Butt JH et al., 2025 [55] | Effects according to frailty status/Frailty index: not frail (27%), more frail (36%), most frail (37%) | Benefits regarding the primary outcome remained consistent across the entire spectrum of frailty (p interaction = 0.77) | Frailty status was not a modifier for either the safety or efficacy of the drug |

| Chimura M et al., 2025 [70] | Efficacy/tolerability by background diuretic therapy/Non-loop (12.6%), Loop ≤ 40 mg (56%), Loop > 40 mg (21%), Combined (10%) | No interaction was found between baseline diuretic intensity and treatment effect (p interaction = 0.18). Furthermore, finerenone therapy reduced the likelihood of needing loop diuretic dose escalation | The type and dose of background diuretics did not influence finerenone’s performance or safety profile |

| Ostrominski JW et al., 2025 [60] | Analysis by baseline KDIGO kidney risk/Low (35%), Moderate (29%), High/Very High (36%) risk | Clinical efficacy on outcomes and symptoms was maintained across all kidney risk categories (p interaction = 0.24). Reduction in UACR was more pronounced in higher-risk groups | Baseline renal risk profile did not modify clinical results, though antiproteinuric effects were greater in patients with higher baseline risk |

| Ostrominski JW et al., 2025 [66] | Analysis based on insulin resistance (eGDR)/5851 (98%) with calculable eGDR | The benefits on CV death and total HF events were consistent across estimated glucose disposal rate (eGDR) categories (p interaction = 0.64), as was the effect on new-onset diabetes (p = 0.36) | Insulin resistance status did not act as a modifier for the drug’s safety or efficacy |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tinti, M.D.; De Gennaro, L.; Limonta, R.; De Maria, R.; Carigi, S.; Bianco, M.; Di Nora, C.; Manca, P.; Matassini, M.V.; Rizzello, V.; et al. Finerenone: Extending MRAs Prognostic Benefit to the Recently Hospitalized and More Symptomatic Patient with HFpEF. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 8730. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14248730

Tinti MD, De Gennaro L, Limonta R, De Maria R, Carigi S, Bianco M, Di Nora C, Manca P, Matassini MV, Rizzello V, et al. Finerenone: Extending MRAs Prognostic Benefit to the Recently Hospitalized and More Symptomatic Patient with HFpEF. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(24):8730. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14248730

Chicago/Turabian StyleTinti, Maria Denitza, Luisa De Gennaro, Raul Limonta, Renata De Maria, Samuela Carigi, Matteo Bianco, Concetta Di Nora, Paolo Manca, Maria Vittoria Matassini, Vittoria Rizzello, and et al. 2025. "Finerenone: Extending MRAs Prognostic Benefit to the Recently Hospitalized and More Symptomatic Patient with HFpEF" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 24: 8730. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14248730

APA StyleTinti, M. D., De Gennaro, L., Limonta, R., De Maria, R., Carigi, S., Bianco, M., Di Nora, C., Manca, P., Matassini, M. V., Rizzello, V., D’Elia, E., Benvenuto, M., Cittar, M., Halasz, G., Iacoviello, M., Gabrielli, D., Colivicchi, F., Bilato, C., Nardi, F., ... Oliva, F. (2025). Finerenone: Extending MRAs Prognostic Benefit to the Recently Hospitalized and More Symptomatic Patient with HFpEF. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(24), 8730. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14248730