The Role of Recombinant Human Bone Morphogenetic Protein–2 in Atlantoaxial Arthrodesis: Institutional Predictors and Systematic Review of Outcomes

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Local Case Series

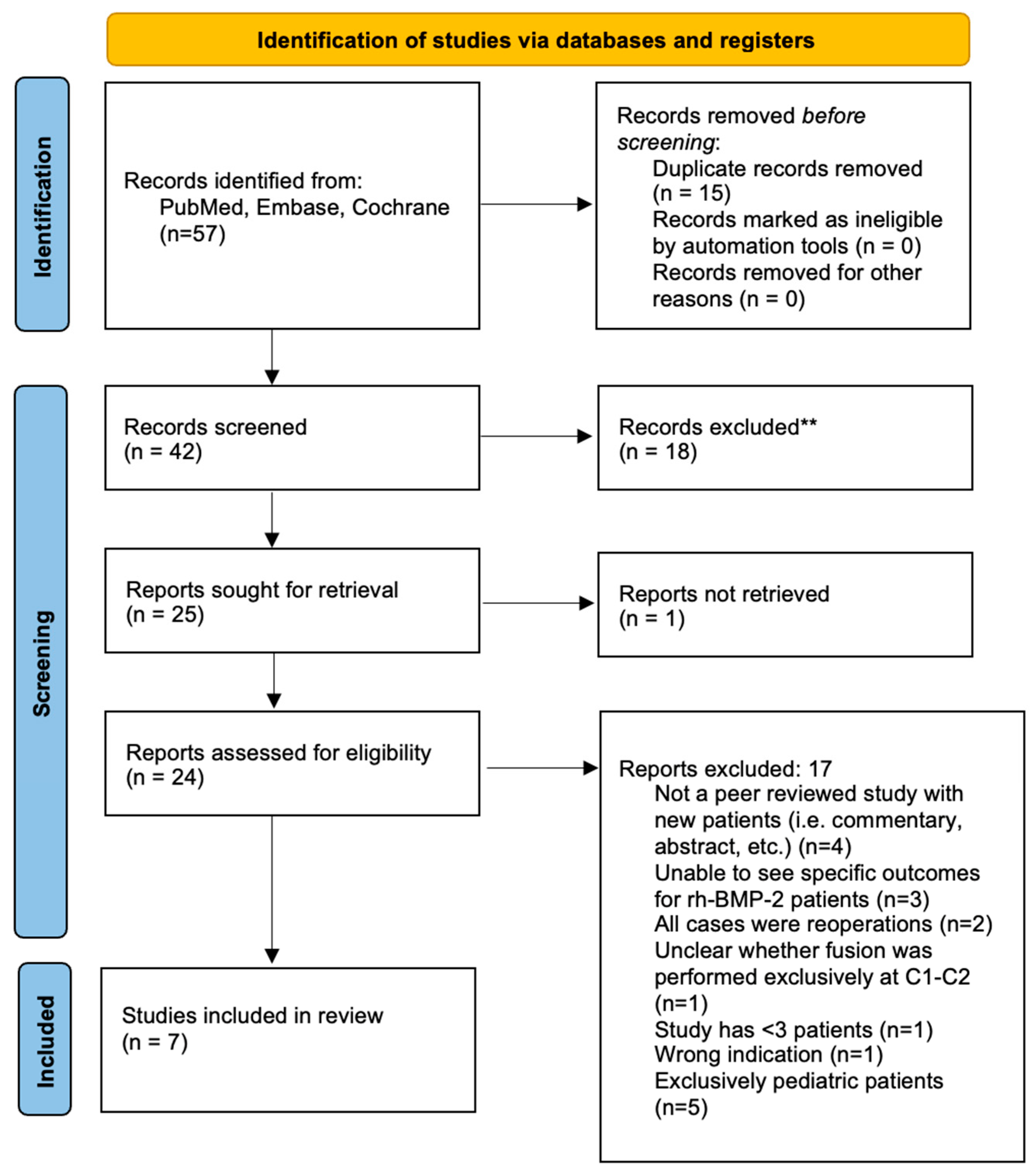

2.2. Systematic Literature Review

3. Results

3.1. Local Cohort: Patient Characteristics and Outcomes

3.2. Predictors of rhBMP-2 Use

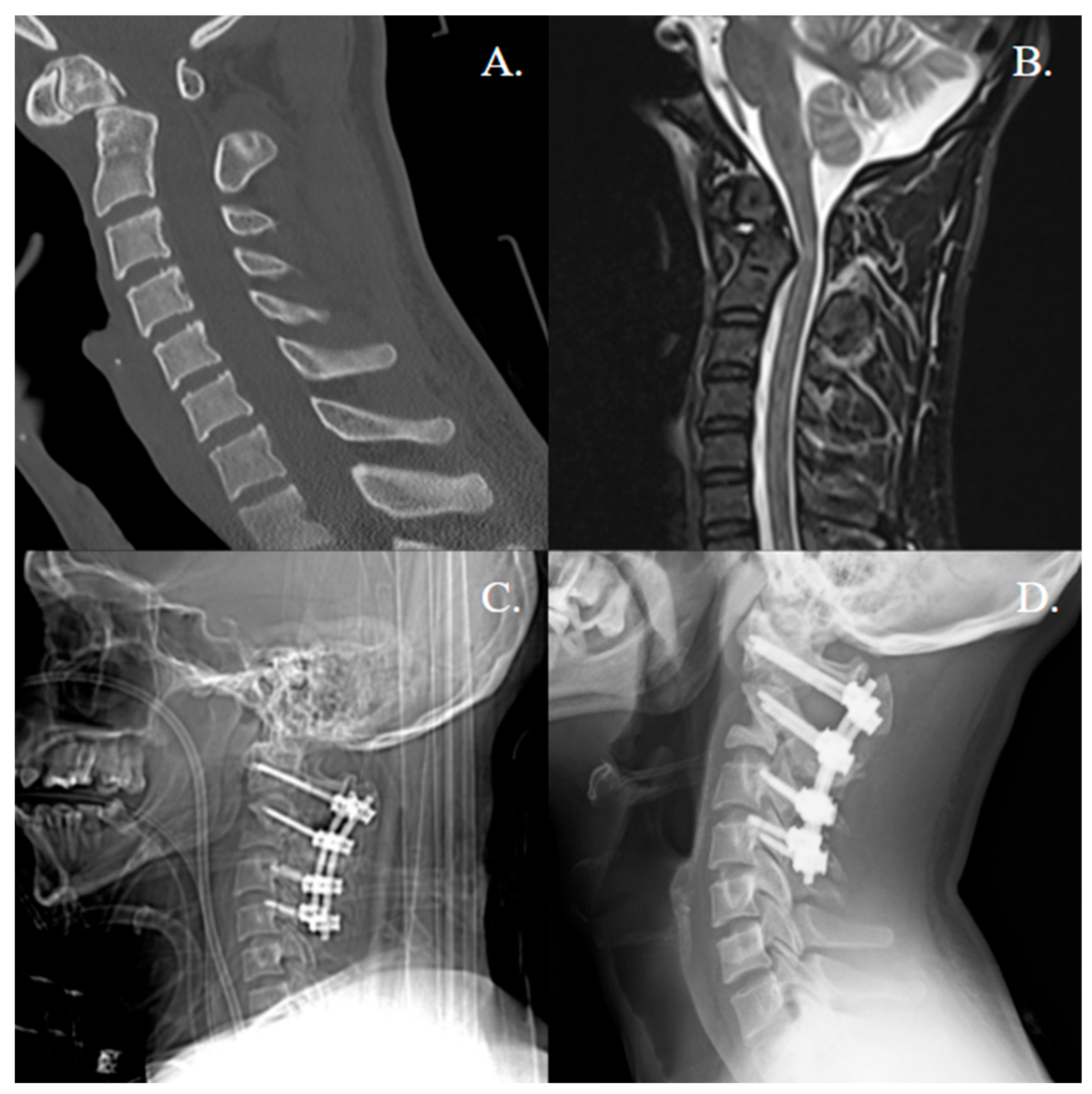

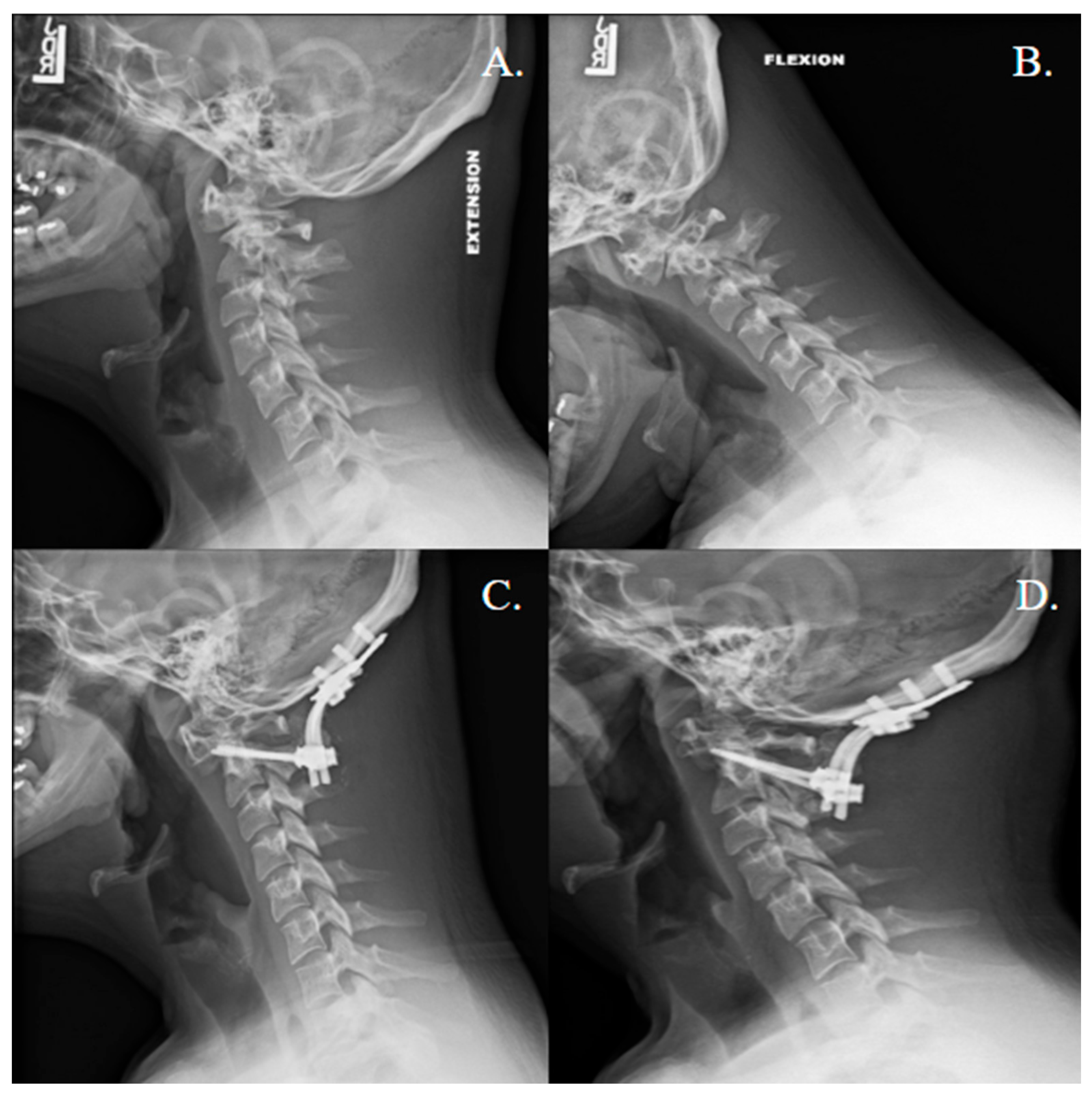

3.3. Isolated Atlantoaxial Fusion Cases

3.4. Systematic Literature Review and Pooled Analysis

4. Discussion

Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Menezes, A.H.; Traynelis, V.C. Anatomy and biomechanics of normal craniovertebral junction (a) and biomechanics of stabilization (b). Child’s Nerv. Syst. 2008, 24, 1091–1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.Y.; Boniello, A.J.; Poorman, C.E.; Chang, A.L.; Wang, S.; Passias, P.G. A review of the diagnosis and treatment of atlantoaxial dislocations. Glob. Spine J. 2014, 4, 197–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Li, S.; Liu, H.; Guo, Q.; Guo, X.; Chen, F.; Han, Z.; Ni, B. Comparison of Two Bone Grafting Techniques Applied During Posterior C1–C2 Screw-Rod Fixation and Fusion for Treating Reducible Atlantoaxial Dislocation. World Neurosurg. 2020, 143, e253–e260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, D.S.; Patel, S.A.; DiSilvestro, K.J.; Li, N.Y.; Daniels, A.H. Postoperative complication rates and hazards-model survival analysis of revision surgery following occipitocervical and atlanto-axial fusion. N. Am. Spine Soc. J. 2020, 3, 100017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.D.; Rivera-Lane, K.; Leary, O.P.; Pertsch, N.J.; Niu, T.; Camara-Quintana, J.Q.; A Oyelese, A.; Fridley, J.S.; Gokaslan, Z.L. Supplementation of Screw-Rod C1–C2 Fixation with Posterior Arch Femoral Head Allograft Strut. Oper Neurosurg. 2021, 20, 226–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Y.-Q.; Li, T.; Ma, C.; Qiao, G.-Y.; Yin, Y.-H.; Yu, X.-G. Biomechanical evaluation of two alternative techniques to the Goel-Harms technique for atlantoaxial fixation: C1 lateral mass–C2 bicortical translaminar screw fixation and C1 lateral mass–C2/3 transarticular screw fixation. J. Neurosurg. Spine 2020, 32, 682–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subach, B.R.; Haid, R.W.; Rodts, G.E.; Kaiser, M.G. Bone morphogenetic protein in spinal fusion: Overview and clinical update. Neurosurg. Focus 2001, 10, E3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faundez, A.; Tournier, C.; Garcia, M.; Aunoble, S.; Le Huec, J.-C. Bone morphogenetic protein use in spine surgery—Complications and outcomes: A systematic review. Int. Orthop. 2016, 40, 1309–1319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Molinari, R.W.; Kerr, C.; Kerr, D. Bone morphogenetic protein in pediatric spine fusion surgery. J. Spine Surg. 2016, 2, 9–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epstein, N. Complications due to the use of BMP/INFUSE in spine surgery: The evidence continues to mount. Surg. Neurol. Int. 2013, 4 (Suppl. 5), S343–S352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perri, B.; Cooper, M.; Lauryssen, C.; Anand, N. Adverse swelling associated with use of rh-BMP-2 in anterior cervical discectomy and fusion: A case study. Spine J. 2007, 7, 235–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smucker, J.D.; Rhee, J.M.; Singh, K.; Yoon, S.T.; Heller, J.G. Increased swelling complications associated with off-label usage of rhBMP-2 in the anterior cervical spine. Spine 2006, 31, 2813–2819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hustedt, J.W.; Blizzard, D.J. The Controversy Surrounding Bone Morphogenetic Proteins in the Spine: A Review of Current Re-search. Yale J. Biol. Med. 2014, 87, 549–561. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ong, K.L.; Villarraga, M.L.; Lau, E.; Carreon, L.Y.M.; Kurtz, S.M.; Glassman, S.D. Off-label use of bone morphogenetic proteins in the United States using administrative data. Spine 2010, 35, 1794–1800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bannwarth, M.; Smith, J.S.; Bess, S.; Klineberg, E.O.; Ames, C.P.; Mundis, G.M.; Kim, H.J.; Lafage, R.; Gupta, M.C.; Burton, D.C.; et al. Use of rhBMP-2 for adult spinal deformity surgery: Patterns of usage and changes over the past decade. Neurosurg. Focus 2021, 50, E4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ROBINS-I Tool|Cochrane Methods. Available online: https://methods.cochrane.org/methods-cochrane/robins-i-tool (accessed on 9 April 2022).

- Brockmeyer, D.L.; Sivakumar, W.; Mazur, M.D.; Sayama, C.M.; Goldstein, H.E.; Lew, S.M.; Hankinson, T.C.; Anderson, R.C.; Jea, A.; Aldana, P.R.; et al. Identifying Factors Predictive of Atlantoaxial Fusion Failure in Pediatric Patients: Lessons Learned From a Retrospective Pediatric Craniocervical Society Study. Spine 2018, 43, 754–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desai, R.; Stevenson, C.B.; Crawford, A.H.; Durrani, A.A.; Mangano, F.T.D. C-1 lateral mass screw fixation in children with atlantoaxial instability: Case series and technical report. J. Spinal Disord. Tech. 2010, 23, 474–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guppy, K.H.; Lee, D.J.; Harris, J.; Brara, H.S. Reoperation for Symptomatic Nonunions in Atlantoaxial (C1–C2) Fusions with and without Bone Morphogenetic Protein: A Cohort of 108 Patients with >2 Years Follow-Up. World Neurosurg. 2019, 121, e458–e466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamilton, D.K.; Smith, J.S.; Reames, D.L.; Williams, B.J.; Shaffrey, C. Use of recombinant human bone morphogenetic protein-2 as an adjunct for instrumented posterior arthrodesis in the occipital cervical region: An analysis of safety, efficacy, and dosing. J. Craniovertebral Junction Spine 2010, 1, 107–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haque, A.; Price, A.V.; Sklar, F.H.; Swift, D.M.; Weprin, B.E.; Sacco, D.J. Screw fixation of the upper cervical spine in the pediatric population. J. Neurosurg. Pediatr. 2009, 3, 529–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hood, B.; Hamilton, D.K.; Smith, J.S.; Dididze, M.; Shaffrey, C.; Levi, A.D. The use of allograft and recombinant human bone morphogenetic protein for instrumented atlantoaxial fusions. World Neurosurg. 2014, 82, 1369–1373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Savage, J.G.; Fulkerson, D.H.; Sen, A.N.; Thomas, J.G.; Jea, A. Fixation with C-2 laminar screws in occipitocervical or C1–2 constructs in children 5 years of age or younger: A series of 18 patients. J. Neurosurg. Pediatr. 2014, 14, 87–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sayama, C.; Hadley, C.; Monaco, G.N.; Sen, A.; Brayton, A.; Briceño, V.; Tran, B.H.; Ryan, S.L.; Luerssen, T.G.; Fulkerson, D.; et al. The efficacy of routine use of recombinant human bone morphogenetic protein–2 in occipitocervical and atlantoaxial fusions of the pediatric spine: A minimum of 12 months’ follow-up with computed tomography. J. Neurosurg. Pediatr. 2015, 16, 14–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siemionow, K.; Hansdorfer, M.; Mardjetko, S.; Janusz, P. Complications in Adult Patients with Down Syndrome Undergoing Cervical Spine Surgery Using Current Instrumentation Techniques and rhBMP-2: A Long-Term Follow-Up. J. Neurol. Surg. A Cent. Eur. Neurosurg. 2017, 78, 113–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Traynelis, V.C.; Fontes, R.B.V.; Abode-Iyamah, K.O.; Cox, E.M.; Greenlee, J.D. Posterior fusion for fragility type 2 odontoid fractures. J. Neurosurg. Spine 2021, 35, 644–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, L.; Chang, Z.; He, B.; Liu, T.; Wang, X.; Guo, H.; Hao, D. Efficacy of rhBMP-2 versus iliac crest bone graft for posterior C1–C2 fusion in patients older than 60 years. Orthopedics 2014, 37, e51–e57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenke, L.G.; Betz, R.R.; Harms, J.; Bridwell, K.H.; Clements, D.H.; Lowe, T.G.; Blanke, K. Adolescent idiopathic scoliosis: A new classification to determine extent of spinal arthrodesis. J. Bone Jt. Surg. Am. 2001, 83, 1169–1181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishida, W.; Ramhmdani, S.; Xia, Y.; Kosztowski, T.A.; Xu, R.; Choi, J.; Ramos, R.D.l.G.; Elder, B.D.; Theodore, N.; Gokaslan, Z.L.; et al. Use of Recombinant Human Bone Morphogenetic Protein-2 at the C1–C2 Lateral Articulation without Posterior Structural Bone Graft in Posterior Atlantoaxial Fusion in Adult Patients. World Neurosurg. 2019, 123, e69–e76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brodell, D.W.; Jain, A.; Elfar, J.C.; Mesfin, A. National trends in the management of central cord syndrome: An analysis of 16,134 patients. Spine J. 2015, 15, 435–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- France, J.C.; Schuster, J.M.; Moran, K.; Dettori, J.R. Iliac Crest Bone Graft in Lumbar Fusion: The Effectiveness and Safety Compared with Local Bone Graft, and Graft Site Morbidity Comparing a Single-Incision Midline Approach with a Two-Incision Traditional Approach. Glob. Spine J. 2015, 5, 195–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, S.; Wang, G.; Yang, J.; Zhang, S.; Song, Y.; Wang, Q. Anterior debridement, bone grafting and fixation for cervical spine tuberculosis: An iliac bone graft versus a structural manubrium graft. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 2022, 23, 236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hofstetter, C.P.; Hofer, A.S.; Levi, A.D. Exploratory meta-analysis on dose-related efficacy and morbidity of bone morphogenetic protein in spinal arthrodesis surgery. J. Neurosurg. Spine 2016, 24, 457–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Stefano, F.A.; Elarjani, T.; Burks, J.D.; Burks, S.S.; Levi, A.D. Dose Adjustment Associated Complications of Bone Morphogenetic Protein: A Longitudinal Assessment. World Neurosurg. 2021, 156, e64–e71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinberg, D.S.; Eoh, J.H.; Manz, W.J.; Fakunle, O.P.; Dawes, A.M.; Park, E.T.; Rhee, J.M. Off-label usage of RhBMP-2 in posterior cervical fusion is not associated with early increased complication rate and has similar clinical outcomes. Spine J. 2022, 22, 1079–1088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crawford, C.H.I.; Carreon, L.Y.M.; McGinnis, M.D.; Campbell, M.J.; Glassman, S.D. Perioperative complications of recombinant human bone morphogenetic protein-2 on an absorbable collagen sponge versus iliac crest bone graft for posterior cervical arthrodesis. Spine 2009, 34, 1390–1394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iyer, S.; Kim, H.J.; Bao, H.; Smith, J.S.; Gupta, M.; Albert, T.J.; Protopsaltis, T.S.; Mundis, G.M.; Passias, P.; Neuman, B.J.; et al. The Posterior Use of BMP-2 in Cervical Deformity Surgery Does Not Result in Increased Early Complications: A Prospective Multicenter Study. Glob. Spine J. 2018, 8, 622–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joaquim, A.F.; Osorio, J.A.; Riew, K.D. Occipitocervical Fixation: General Considerations and Surgical Technique. Glob. Spine J. 2019, 10, 647–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Brahimaj, B.C.; Khanna, R.; Kerolus, M.G.; Tan, L.A.; David, B.T.; Fessler, R.G. Posterior atlantoaxial fusion: A comprehensive review of surgical techniques and relevant vascular anomalies. J. Spine Surg. 2020, 6, 164–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghostine, S.S.; E Kaloostian, P.; Ordookhanian, C.; Kaloostian, S.; Zarrini, P.; Kim, T.; Scibelli, S.; Clark-Schoeb, S.J.; Samudrala, S.; Lauryssen, C.; et al. Improving C1–C2 Complex Fusion Rates: An Alternate Approach. Cureus 2017, 9, e1887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Non-rhBMP-2 Group | rhBMP-2 Group | Overall | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (N = 25) | (N = 24) | (N = 49) | ||

| Age at Surgery: Mean (SD) | 66.85 (18.47) | 56.56 (25.84) | 61.82 (22.75) | 0.118 |

| Gender: | 0.333 | |||

| Male: N (%) | 21 (84.0) | 12 (50.0) | 28 (57.14) | |

| Female: N (%) | 16 (64.0) | 12 (50.0) | 21 (42.86) | |

| Fusion Indication: | ||||

| Traumatic: N (%) | 20 (80.0) | 11 (45.83) | 31 (63.27) | 0.019 |

| Congenital/Deformity: N (%) | 2 (8.0) | 4 (16.67) | 6 (12.24) | 0.417 |

| Degenerative: N (%) | 3 (12.0) | 9 (37.50) | 12 (24.49) | 0.051 |

| Prior Cervical Surgery: | 0.977 | |||

| Yes (%) | 1 (4.0) | 1 (4.17) | 2 (4.08) | |

| No (%) | 21 (96.0) | 23 (95.83) | 47 (95.92) | |

| Number of Levels Fused: Mean (SD) | 3.76 (1.85) | 3.58 (1.69) | 3.67 (1.76) | 0.729 |

| Atlantoaxial Fusion Only: | 0.481 | |||

| Yes (%) | 6 (24.0) | 8 (33.33) | 14 (28.57) | |

| No (%) | 19 (76.0) | 16 (66.67) | 35 (71.43) | |

| Concomitant Decompression: | 0.306 | |||

| Yes (%) | 16 (64.0) | 13 (54.17) | 29 (59.18) | |

| No (%) | 9 (36.0) | 11 (45.83) | 20 (40.82) | |

| Number of Levels Decompressed: | 1.72 (2.07) | 2.21 (1.98) | 1.96 (2.02) | 0.403 |

| Mean (SD) | ||||

| Follow-up Time (Months): | 13.52 (11.72) | 17.88 (20.19) | 15.65 (16.40) | 0.364 |

| Mean (SD) | ||||

| Pain Reported Post-Operatively: | 0.467 | |||

| Yes (%) | 5 (20.0) | 7 (29.17) | 12 (24.49) | |

| No (%) | 20 (80.0) | 17 (70.83) | 37 (75.51) | |

| Fusion or Early Signs on Post-Op | 0.678 | |||

| Imaging: | ||||

| Yes (%) | 22 (88.0) | 22 (91.67) | 44 (89.80) | |

| No (%) | 3 (12.0) | 2 (8.33) | 5 (20.10) | |

| Post-Operative Imaging Used: | 0.467 | |||

| X-Ray: N (%) | 12 (48.0) | 13 (52.0) | 25 (51.02) | |

| CT: N (%) | 13 (54.17) | 11 (45.83) | 24 (49.0) | |

| Post-Operative Instability: | 0.043 | |||

| Yes (%) | 4 (16.0) | 0 (0) | 4 (8.16) | |

| No (%) | 21 (84.0) | 24 (100) | 45 (91.84) | |

| Complications: | 0.702 | |||

| Yes (%) | 5 (25.0) | 3 (12.5) | 8 (16.33) | |

| No (%) | 20 (75.0) | 21 (87.5) | 41 (83.67) | |

| Reoperation: | 0.977 | |||

| Yes (%) | 1 (4.0) | 1 (4.17) | 2 (4.08) | |

| No (%) | 24 (96.0) | 23 (95.83) | 47 (95.52) | |

| Pseudoarthrosis: | 0.327 | |||

| Yes (%) | 1 (4.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (2.04) | |

| No (%) | 24 (96.0) | 24 (100.0) | 48 (97.96) | |

| Instrument Breakage/Hardware | 1.000 | |||

| Malfunction | ||||

| Yes (%) | 2 (8.0) | 2 (8.33) | 4 (8.16) | |

| No (%) | 23 (92.0) | 22 (91.67) | 45 (91.84) | |

| Wound Complication: | 0.327 | |||

| Yes (%) | 1 (4.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (2.04) | |

| No (%) | 24 (96.0) | 24 (100.0) | 48 (97.96) |

| Odds of Receiving rhBMP-2 (95% CI) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|

| Age | 0.98 (0.927–1.011) | 0.168 |

| Gender | 0.42 (0.101–1.595) | 0.215 |

| Number of levels fused | 0.87 (0.547–1.331) | 0.542 |

| Degenerative indication | 7.96 (1.452–62.619) | 0.027 |

| Congenital indication | 0.98 (0.054–17.609) | 0.990 |

| Traumatic indication | 0.21 (0.055–0.717) | 0.016 |

| Concurrent decompression | 1.92 (0.388–10.41) | 0.425 |

| Prior surgery | 0.721 (0.025–20.980) | 0.830 |

| ID | Age, Sex | Indication | Construct | Concurrent C1–2 Decompression (Y/N) | Arthrodesis Material | Follow Up (Months) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 45, M | Degenerative | C1 lateral mass screws bilaterally, C2 translaminar screws bilaterally, titanium rod | N | DBX, rhBMP-2 (XX small kit, 0.82 mg/mL) | 26 |

| 2 | 29, F | Trauma | C1 lateral mass screws bilaterally, C2 translaminar screws bilaterally. Sublaminar Songer cables at C1 and posterior to C2 spinous process, titanium rod | N | DBX, femoral head structural allograft, rhBMP-2 (XX small kit, 0.82 mg/mL) | 25 |

| 3 | 51, M | Trauma | C1 lateral mass screws bilaterally, 1 C2 pars and 1 C2 pedicle screw, titanium rods | N | rhBMP-2 (X small kit, 1.62 mg/mL) | 3 |

| 4 | 28, F | Trauma | C1 lateral mass screws bilaterally, C2 pedicle screws bilaterally, titanium rod | N | DBX, local autograft, rh-BMP-2 (half of a XX small kit, 0.41 mg/mL) | 20 |

| 5 | 80, F | Trauma | C1 lateral mass screws bilaterally, C2 pedicle screws bilaterally, titanium rod, cross connector at C1 | N | DBX, local autograft, rhBMP-2 (X small kit, 1.62 mg/mL) | 4 |

| 6 | 33, F | Trauma | C1 lateral mass screws bilaterally, C2 pedicle screws bilaterally, titanium rod | N | DBX, local autograft, rhBMP-2 (half of a XX small, 0.41 mg/mL) | 69 |

| 7 | 77, M | Trauma | C1 lateral mass screws bilaterally, C2 pedicle screws bilaterally | Y | DBX, local autograft, rh-BMP-2 (XX small kit, 0.82 mg/mL) | 10 |

| 8 | 80, M | Trauma | C1 lateral mass screws bilaterally, C2 pedicle screws bilaterally, titanium rods | Y | DBX, local autograft, rh-BMP-2 (XX small kit, 0.82 mg/mL) | 3 |

| ID | Surgical Complications | Revision (Y/N) | Fusion on Latest Follow-Up Imaging (Y/N) | Atlantoaxial Instability Clinically or in Dynamic Imaging? (Y/N) | Imaging Follow Up (Time, Type) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | C1 screw breakage | N, avoided re-op due to complete bony fusion | Y | N | 25 months, X-ray |

| 2 | None | N | Y | N | 25 months, X-ray |

| 3 | None | N | Early signs of fusion | N | 3 months, CT |

| 4 | None | N | Y | N | 19 months, CT |

| 5 | None | N | N | N | 4 months, CT |

| 6 | None | N | Y | N | 15 months, X-ray |

| 7 | None | N | Early signs of fusion | N | 3 months, CT |

| 8 | None | N | Early signs of fusion | N | 3 months, X-ray |

| Author, Year (Journal) | Number of Patients | Mean rhBMP-2 Dose (mg) | ROBINS-1 Risk of Bias | Fusion Definition | Successful Fusion | Complications | Revision Surgeries | Other Fusion Materials Used |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Guppy et al., 2019 * (World Neurosurgery) [20] | 58 | unreported | Low | Lack of symptomatic nonunion | 58/58 | 0/58 | 0/58 | N/a |

| Hamilton et al., 2010 (Journal of Craniovertebral Junction and Spine) [21] | 7 | 2.38 | Moderate | Lenke classification assessed on CT | 7/7 | 0/7 | 0/7 | Morselized allograft |

| Hood et al., 2014 (World Neurosurgery) [23] | 52 | 4.5 | Low | Lenke classification assessed on plain radiograph and CT | 50/50 (2 patients lost during follow-up) | 0/50 | 0/50 | Cancellous allograft (20 patients) Iiliac allograft (24 patients) |

| Siemionow et al., 2017 * (J Neurol Surg A Cent Euro Neurosurgery) [26] | 3 | 4 | Moderate | N/a | 2/3 | 2/3 (adjacent segment instability + nonunion in 1 patient, pseudoarthrosis in other patients) | 1/3 (pseudoarthrosis and progressive instability) | Allograft (unspecified, 2 patients) Iliac crest autograft (1 patient) |

| Traynelis et al., 2021 (JNS Spine) [27] | 3 | N/a | Low | No motion on dynamic radiographs, intact hardware, and no lucencies around the graft | 3/3 | N/a | N/a | Allograft (unspecified, 3) |

| Yan et al., 2014 * (Orthopedics) [28] | 68 | N/a | Moderate | Lack or presence of fusion on post-operative CT scan | 56/68 | 7/68 (wound complications in 6 patients, dural tear in 1 patient) | 2/68 (wound-related) | Iliac crest bone graft (all patients) |

| Ishida et al. 2019 (World Neurosurgery) [30] | 69 | 2.5 | Moderate | Stability on plain radiograph, dynamic radiographs, and/or CT scan | 65/69 | 19/69 (1 postoperative difficulty in phonation, 1 incidental durotomy, 2 adjacent segment disease, | 7/69 (instrumentation breakage) | 13/69 hydroxyapatite 17/69 local autograft chips 24/69 local autograft and allograft chips |

| Total | 260 | 3.32 across reported studies | - | - | 241/260 (92.7%) | 2 postoperative dysphagia, | 10/260 (3.8%) | - |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Taman, M.; Teshome, A.A.; Ganga, A.; Persad, E.M.; Leary, O.P.; Gokcebel, S.; Sastry, R.; Sullivan, P.Z.; Chang, K.-E.; Oyelese, A.A.; et al. The Role of Recombinant Human Bone Morphogenetic Protein–2 in Atlantoaxial Arthrodesis: Institutional Predictors and Systematic Review of Outcomes. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 8731. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14248731

Taman M, Teshome AA, Ganga A, Persad EM, Leary OP, Gokcebel S, Sastry R, Sullivan PZ, Chang K-E, Oyelese AA, et al. The Role of Recombinant Human Bone Morphogenetic Protein–2 in Atlantoaxial Arthrodesis: Institutional Predictors and Systematic Review of Outcomes. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(24):8731. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14248731

Chicago/Turabian StyleTaman, Mazen, Abigail A. Teshome, Arjun Ganga, Elijah M. Persad, Owen P. Leary, Senay Gokcebel, Rahul Sastry, Patricia Zadnik Sullivan, Ki-Eun Chang, Adetokunbo A. Oyelese, and et al. 2025. "The Role of Recombinant Human Bone Morphogenetic Protein–2 in Atlantoaxial Arthrodesis: Institutional Predictors and Systematic Review of Outcomes" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 24: 8731. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14248731

APA StyleTaman, M., Teshome, A. A., Ganga, A., Persad, E. M., Leary, O. P., Gokcebel, S., Sastry, R., Sullivan, P. Z., Chang, K.-E., Oyelese, A. A., Gokaslan, Z. L., Fridley, J. S., & Niu, T. (2025). The Role of Recombinant Human Bone Morphogenetic Protein–2 in Atlantoaxial Arthrodesis: Institutional Predictors and Systematic Review of Outcomes. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(24), 8731. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14248731