Impact of Nicotine-Free Electronic Cigarettes on Cardiovascular Health: A Systematic Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

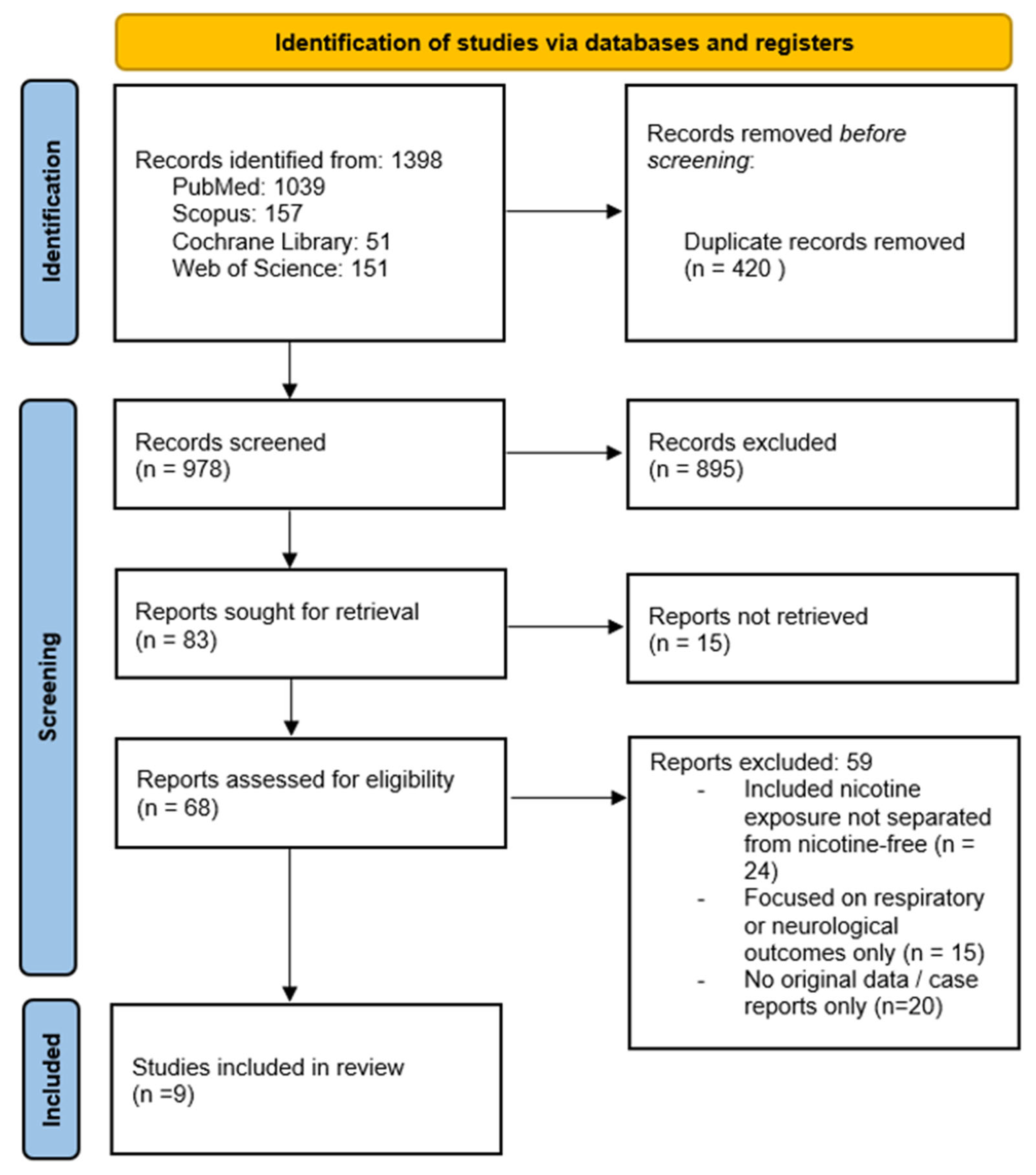

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Literature Search Strategy

2.2. Risk of Bias Assessment

2.3. Data Synthesis

3. Results

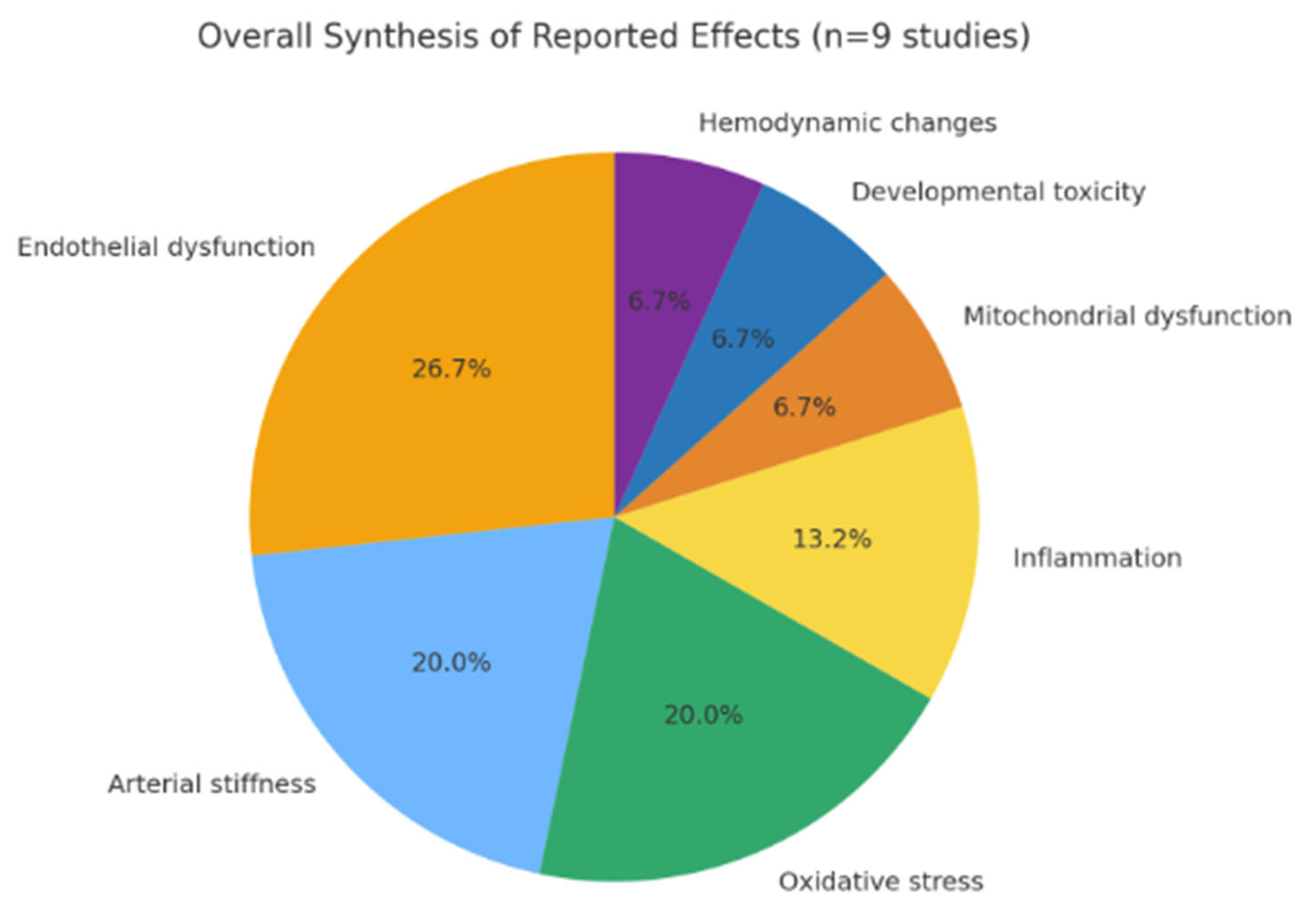

3.1. Qualitative Synthesis

3.2. Animal and Embryonic Models

3.3. Human Studies

3.4. Risk of Bias

4. Discussion

4.1. Comparison with the Existing Literature

4.2. Arrhythmias and Blood Pressure Effects

Narrative Synthesis

4.3. Interpretation

4.4. Strengths and Limitations

4.5. Clinical and Public Health Implications

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BP | Blood pressure |

| ENDS | Electronic nicotine delivery system |

| FDA | Food and Drug Administration |

| FMD | Flow-mediated dilation |

| MRI | Magnetic resonance imaging |

| NC | Nicotine containing |

| NF | Nicotine free |

| NFEC | Nicotine-free e-cigarettes |

| PG | Propylene glycol |

| RCT | Randomized controlled trials |

| ROS | Reactive oxygen species |

| TPD | Tobacco Products Directive |

| VG | Vegetable glycerin |

References

- Cullen, K.A.; Ambrose, B.K.; Gentzke, A.S.; Apelberg, B.J.; Jamal, A.; King, B.A. Notes from the Field: Use of Electronic Cigarettes and Any Tobacco Product Among Middle and High School Students—United States, 2011–2018. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2018, 67, 1276–1277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammond, D.; Reid, J.L.; Rynard, V.L.; Fong, G.T.; Cummings, K.M.; McNeill, A.; Hitchman, S.C.; Thrasher, J.F.; Goniewicz, M.L.; Bansal-Travers, M.; et al. Prevalence of Vaping and Smoking Among Adolescents in Canada, England, and the United States: Repeat National Cross-Sectional Surveys. BMJ 2019, 365, l2219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bernat, D.; Gasquet, N.; O’Dare Wilson, K.; Porter, L.; Choi, K. Electronic Cigarette Harm and Benefit Perceptions and Use Among Youth. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2018, 55, 361–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aly, A.S.; Mamikutty, R.; Marhazlinda, J. Association between Harmful and Addictive Perceptions of E-Cigarettes and E-Cigarette Use among Adolescents and Youth—A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Children 2022, 9, 1678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sapru, S.; Vardhan, M.; Li, Q.; Guo, Y.; Li, X.; Saxena, D. E-Cigarettes Use in the United States: Reasons for Use, Perceptions, and Effects on Health. BMC Public Health 2020, 20, 1418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benowitz, N.L.; Fraiman, J.B. Cardiovascular Effects of Electronic Cigarettes. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2017, 14, 447–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moheimani, R.S.; Bhetraratana, M.; Yin, F.; Peters, K.M.; Gornbein, J.; Araujo, J.A.; Middlekauff, H.R. Increased Cardiac Sympathetic Activity and Oxidative Stress in Habitual Electronic Cigarette Users: Implications for Cardiovascular Risk. JAMA Cardiol. 2017, 2, 278–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olfert, I.M.; DeVallance, E.; Hoskinson, H.; Branyan, K.W.; Clayton, S.; Pitzer, C.R.; Sullivan, D.P.; Wu, Z.; Klinkhachorn, P.; Chantler, P.D.; et al. Chronic exposure to electronic cigarettes results in impaired cardiovascular function in mice. J. Appl. Physiol. 2018, 124, 573–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, M.; Villarreal, A.; Bozhilov, K.; Lin, S.; Talbot, P. Metal and Silicate Particles Including Nanoparticles Are Present in Electronic Cigarette Cartomizer Fluid and Aerosol. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e57987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sassano, M.F.; Davis, E.S.; Keating, J.E.; Zorn, B.T.; Kochar, T.K.; Wolfgang, M.C.; Glish, G.L.; Tarran, R. Evaluation of E-Liquid Toxicity Using an Open-Source High-Throughput Screening Assay. PLoS Biol. 2018, 16, e2003904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bitzer, Z.T.; Goel, R.; Reilly, S.M.; Elias, R.J.; Silakov, A.; Foulds, J.; Muscat, J.; Richie, J.P. Effects of Flavoring Chemicals on Free Radical Formation in Electronic Cigarette Aerosols. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2018, 120, 72–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caporale, A.; Langham, M.C.; Guo, W.; Johncola, A.; Chatterjee, S.; Wehrli, F.W. Acute Effects of Electronic Cigarette Aerosol Inhalation on Vascular Function Detected at Quantitative MRI. Radiology 2019, 293, 97–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, R.P.; Luo, W.; Pankow, J.F.; Strongin, R.M.; Peyton, D.H. Hidden Formaldehyde in E-Cigarette Aerosols. N. Engl. J. Med. 2015, 372, 392–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sleiman, M.; Logue, J.M.; Montesinos, V.N.; Russell, M.L.; Litter, M.I.; Gundel, L.A.; Destaillats, H. Emissions from Electronic Cigarettes: Key Parameters Affecting the Release of Harmful Chemicals. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2016, 50, 9644–9651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clapp, P.W.; Jaspers, I. Electronic Cigarettes: Their Constituents and Potential Links to Asthma. Curr. Allergy Asthma Rep. 2017, 17, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muthumalage, T.; Prinz, M.; Ansah, K.O.; Gerloff, J.; Sundar, I.K.; Rahman, I. Inflammatory and Oxidative Responses Induced by Exposure to Commonly Used E-Cigarette Flavoring Chemicals and Flavored E-Liquids Without Nicotine. Front. Physiol. 2018, 8, 1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allen, J.G.; Flanigan, S.S.; LeBlanc, M.; Vallarino, J.; MacNaughton, P.; Stewart, J.H.; Christiani, D.C. Flavoring Chemicals in E-Cigarettes: Diacetyl, 2,3-Pentanedione, and Acetoin. Environ. Health Perspect. 2016, 124, 733–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piechowski, J.M.; Bagatto, B. Cardiovascular Function During Early Development Is Suppressed by Cinnamon-Flavored, Nicotine-Free Electronic Cigarette Vapor. Birth Defects Res. 2021, 113, 1215–1223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaumont, M.; de Becker, B.; Zaher, W.; Culie, A.; Deprez, G.; Mélot, C.; Reye, F.; Van Antwerpen, P.; Deldicque, L.; Debbas, N.; et al. Differential Effects of E-Cigarette on Microvascular Endothelial Function, Arterial Stiffness and Oxidative Stress. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 10378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Franzen, K.F.; Willig, J.; Cayo Talavera, S.; Meusel, M.; Sayk, F.; Reppel, M.; Dalhoff, K.; Mortensen, K.; Völkel, N.; Droemann, D.; et al. E-Cigarettes and Cigarettes Worsen Peripheral and Central Hemodynamics as well as arterial stiffness. Vasc. Med. 2018, 23, 419–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carnevale, R.; Sciarretta, S.; Violi, F.; Nocella, C.; Loffredo, L.; Perri, L.; Marullo, A.G.; De Falco, E.; Chimenti, I.; Peruzzi, M.; et al. Acute Impact of Tobacco vs Electronic Cigarette Smoking on Oxidative Stress and Vascular Function. Chest 2016, 150, 606–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Madison, M.C.; Landers, C.T.; Gu, B.-H.; Chang, C.-Y.; Tung, H.-Y.; You, R.; Hong, M.J.; Baghaei, N.; Song, L.-Z.; Porter, P.; et al. Electronic Cigarettes Disrupt Lung Lipid Homeostasis and Innate Immunity Independent of Nicotine. J. Clin. Invest. 2019, 129, 4290–4304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espinoza-Derout, J.; Shao, X.M.; Bankole, E.; Hasan, K.M.; Haley, R.; Wong, T.; Presley, J.; Hollywood, E.G.; Schivo, M.; Kloner, R.A.; et al. Chronic Intermittent Electronic Cigarette Exposure Induces Cardiac Dysfunction and Atherosclerosis in apolipoprotein-E knockout mice. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2019, 316, H1236–H1247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papaioannou, T.G.; Aggeli, C.; Tousoulis, D. Does Nicotine-free Electronic Cigarette Vaping Affect Aortic Stiffness Independently of Heart Rate? Radiology 2019, 293, E1–E2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, H.; Li, H.; Wang, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Chen, X.; Li, L.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Q.; Xu, F. Aerosolized Nicotine-Free E-Liquid Base Constituents Exacerbate Mitochondrial Dysfunction and Endothelial Glycocalyx Shedding via the AKT/GSK3β-mPTP Pathway in Lung Injury Models. Respir. Res. 2025, 26, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGrath-Morrow, S.A.; Hayashi, M.; Aherrera, A.; Lopez, A.; Malinina, A.; Collaco, J.M.; Neptune, E.; Klein, J.D.; Winickoff, J.P.; Breysse, P.; et al. The Effects of Electronic Cigarette Emissions on Systemic Cotinine Levels, Weight and Postnatal Lung Growth in Neonatal Mice. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0118344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaumont, M.; van de Borne, P.; Bernard, A.; Van Muylem, A.; Deprez, G.; Ullmo, J.; Starczewska, E.; Briki, R.; de Hemptinne, Q.; Zaher, W.; et al. Fourth-Generation E-Cigarette Vaping Induces Transient Lung Inflammation and gas exchange disturbances: Results from two randomized clinical trials. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell. Mol. Physiol. 2019, 316, L705–L719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goebel, I.; Mohr, T.; Axt, P.N.; Watz, H.; Trinkmann, F.; Weckmann, M.; Drömann, D.; Franzen, K.F. Impact of Heated Tobacco Products, E-Cigarettes, and Combustible Cigarettes on Small Airways and Arterial Stiffness. Toxics 2023, 11, 758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, W.H.; Ong, S.-G.; Zhou, Y.; Tian, L.; Bae, H.R.; Baker, N.; Whitlatch, A.; Wu, J.C.; Mohammadi, L.; Guo, H.; et al. Modeling Cardiovascular Risks of E-Cigarettes With Human-Induced Pluripotent Stem Cell–Derived Endothelial Cells. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2019, 73, 2722–2737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qasim, H.; Karim, Z.A.; Rivera, J.O.; Khasawneh, F.T.; Alshbool, F.Z. Impact of Electronic Cigarettes on the Cardiovascular System. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2017, 6, e006353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meng, X.-C.; Guo, X.-X.; Peng, Z.-Y.; Wang, C.; Liu, R. Acute Effects of Electronic Cigarettes on Vascular Endothelial Function: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of RCTs. Eur. J. Prev. Cardiol. 2023, 30, 425–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stokes, A.C.; Xie, W.; Wilson, A.E.; Yang, H.; Orimoloye, O.A.; Harlow, A.F.; Fetterman, J.L.; DeFilippis, A.P.; Benjamin, E.J.; Robertson, R.M.; et al. Association of Cigarette and Electronic Cigarette Use Patterns with Levels of Inflammatory and Oxidative Stress Biomarkers among U.S. Adults, Population Assessment of Tobacco and Health Study. Circulation 2021, 143, 869–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hooijmans, C.R.; Rovers, M.M.; de Vries, R.B.M.; Leenaars, M.; Ritskes-Hoitinga, M.; Langendam, M.W. SYRCLE’s Risk of Bias Tool for Animal Studies. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2014, 14, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kundu, A.; Feore, A.; Sanchez, S.; Abu-Zarour, N.; Sutton, M.; Sachdeva, K.; Seth, S.; Schwartz, R.; Chaiton, M. Cardiovascular Health Effects of Vaping e-cigarettes: A systematic review and meta-analysis: Systematic Review. Heart 2025, 111, 599–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berlowitz, J.B.; Xie, W.; Harlow, A.F.; Hamburg, N.M.; Blaha, M.J.; Bhatnagar, A.; Benjamin, E.J.; Stokes, A.C. E-Cigarette Use and Risk of Cardiovascular Disease: PATH Cohort Study. Circulation 2022, 145, 1557–1559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, L.C.; Walsh, L.; Martin, B.; McGee, J.; Wood, C.; Kovalcik, K.; Pancras, P.; Haykal-Coates, N.; Ledbetter, A.D.; Davies, D.; et al. Ambient Particulate Matter and Acrolein Co-Exposure Increases Myocardial Dyssynchrony in Mice via TRPA1. Toxicol. Sci. 2019, 167, 559–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talih, S.; Salman, R.; El-Hage, R.; Karam, E.; Karaoghlanian, N.; El-Hellani, A.; Saliba, N.; Shihadeh, A. Characteristics and Toxicant Emissions of JUUL Electronic Cigarettes. Tob. Control 2019, 28, 678–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hassan, M.; Vinagolu-Baur, J.; Li, V.; Frasier, K.; Herrick, G.; Scotto, T.; Rankin, E. E-Cigarettes and Arterial Health: A Review of the Link Between Vaping and Atherosclerosis Progression. World J. Cardiol. 2024, 16, 707–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magna, A.; Polisena, N.; Polisena, L.; Bagnato, C.; Pacella, E.; Carnevale, R.; Nocella, C.; Loffredo, L. The Hidden Dangers: E-Cigarettes, Heated Tobacco, and Their Impact on Oxidative Stress and Atherosclerosis—A Systematic Review and Narrative Synthesis of the Evidence. Antioxidants 2024, 13, 1395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qiu, H.; Zhang, H.; Han, D.D.; Mohammadi, L.; Olgin, J.E.; Springer, M.L.; Derakhshandeh, R.; Wang, X.; Goyal, N.; Navabzadeh, M.; et al. Increased Vulnerability to Atrial and Ventricular Arrhythmias Caused by Different Types of Inhaled Tobacco or Marijuana Products. Heart Rhythm 2023, 20, 76–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jukic, I.; Matulic, I.; Vukovic, J. Effects of Nicotine-Free E-Cigarettes on the Gastrointestinal System: A Systematic Review. Biomedicines 2025, 13, 1998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, L.C.; Ledbetter, A.D.; Haykal-Coates, N.; Cascio, W.E.; Hazari, M.S.; Farraj, A.K. Acrolein Inhalation Alters Myocardial Synchrony and Performance at and Below Exposure Concentrations That Cause Ventilatory Responses. Cardiovasc. Toxicol. 2017, 17, 97–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dimitriadis, K.; Narkiewicz, K.; Leontsinis, I.; Konstantinidis, D.; Mihas, C.; Andrikou, I.; Thomopoulos, C.; Tousoulis, D.; Tsioufis, K. Acute Effects of Electronic and Tobacco Cigarette Smoking on Sympathetic Nerve Activity and Blood Pressure in Humans. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 3237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skotsimara, G.; Antonopoulos, A.S.; Oikonomou, E.; Siasos, G.; Konstantinou, A.; Kollia, M.-E.; Charalambous, G.; Papamikroulis, G.-A.; Vogiatzi, G.; Zaromitidou, M.; et al. E-Cigarette Impact on Cardiovascular Health: A Systematic Review and Narrative Synthesis. Eur. J. Prev. Cardiol. 2019, 26, 1219–1228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheraghi, M.; Amiri, M.; Omidi, F.; Shahidi Bonjar, A.H.; Bakhshi, H.; Vaezi, A.; Nasiri, M.J.; Mirsaeidi, M. Acute Cardiovascular Effects of Electronic Cigarettes: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Eur. Heart J. Open 2024, 4, oeae098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qazi, S.U.; Ansari, M.H.-U.-H.; Ghazanfar, S.; Ghazanfar, S.S.; Farooq, M. Comparison of Acute Effects of E-Cigarettes With and Without Nicotine and Tobacco Cigarettes on Hemodynamic and Endothelial Parameters: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. High Blood Press. Cardiovasc. Prev. 2024, 31, 225–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carll, A.P.; Kucera, C.; Haykal-Coates, N.; Winsett, D.W.; Hazari, M.S. E-Cigarettes and Their Lone Constituents Induce Cardiac Arrhythmia and Conduction Defects in Mice. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 6088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herzog, C.; Jones, A.; Evans, I.; Raut, J.R.; Zikan, M.; Cibula, D.; Wong, A.; Brenner, H.; Richmond, R.; Widschwendter, M. Cigarette Smoking and E-Cigarette Use Induce Shared DNA Methylation Changes Linked to Carcinogenesis. Cancer Res. 2024, 84, 1898–1914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.; McCausland, K.; Jancey, J. Adolescent’s Health Perceptions of E-Cigarettes: A Systematic Review. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2021, 60, 233–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izquierdo-Condoy, J.S.; Naranjo-Lara, P.; Morales-Lapo, E.; Hidalgo, M.R.; Tello-De-la-Torre, A.; Vásconez-Gonzáles, E.; Salazar-Santoliva, C.; Loaiza-Guevara, V.; Rincón Hernández, W.; Becerra, D.A.; et al. Direct Health Implications of E-Cigarette Use: A Systematic Scoping Review with Evidence Assessment. Front. Public Health 2024, 12, 1427752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klonizakis, M.; Gumber, A.; McIntosh, E.; Brose, L.S. Short-Term Cardiovascular Effects of E-Cigarettes in Adults Making a Stop-Smoking Attempt: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Biology 2021, 10, 1208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zong, H.; Hu, Z.; Li, W.; Wang, M.; Zhou, Q.; Li, X.; Liu, H. Electronic Cigarettes and Cardiovascular Disease: Epidemiological and Biological Links. Pflügers Arch.—Eur. J. Physiol. 2024, 476, 875–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leventhal, A.M.; Strong, D.R.; Kirkpatrick, M.G.; Unger, J.B.; Sussman, S.; Riggs, N.R.; Stone, M.D.; Khoddam, R.; Samet, J.M.; Audrain-McGovern, J. Association of Electronic Cigarette Use With Initiation of Combustible Tobacco Product Smoking in Early Adolescence. JAMA 2015, 314, 700–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Study | Model | Tool | Selection Bias | Performance Bias | Detection Bias | Reporting Bias | Overall Risk |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Piechowski et al., 2021 [18] | Zebrafish (animal) | SYRCLE | Unclear | Moderate | Moderate | Low | Moderate |

| Espinoza-Derout et al., 2021 [23] | Mouse (animal) | SYRCLE | Unclear | Moderate | Moderate | Low | Moderate |

| Dai et al., 2025 [25] | Mouse + cells (animal) | SYRCLE | Unclear | Moderate | Moderate | Low | Moderate |

| Carnevale et al., 2016 [21] | Human (crossover) | ROBINS-I | Low | Moderate | Moderate | Low | Moderate |

| Franzen et al., 2018 [20] | Human (clinical) | ROBINS-I | Low | Moderate | Moderate | Low | Moderate |

| Chaumont et al., 2019 [27] | Human (RCT) | RoB2 | Low | Low | Moderate | Low | Low–Moderate |

| Caporale et al., 2019 [12] | Human (MRI) | ROBINS-I | Low | Moderate | Moderate | Low | Moderate |

| Papaioannou, 2019 [24] | Human (MRI) | ROBINS-I | Low | Moderate | Moderate | Low | Moderate |

| Goebel et al., 2023 [28] | Human (crossover) | ROBINS-I | Low | Moderate | Moderate | Low | Moderate |

| Author | Year | Model | Exposure | Main Findings | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Piechowski et al. [18] | 2021 | Animal (zebrafish embryos) | High-dose NFEC aerosols infused into dechlorinated water | Decreased end systolic and diastolic volume, stroke volume, heart rate, cardiac output, and red blood cell density | Experimental, high dose only |

| Espinoza-Derout et al. [23] | 2021 | Animal (mouse) | Short-term exposure | Hyperlipidemia, sympathetic dominance, DNA damage, and macrophage activation | Short exposure duration |

| Dai et al. [25] | 2025 | Animal (mouse + endothelial cells) | NFEC aerosol exposure | Dose-dependent increases in mitochondrial ROS production, enhanced endothelial permeability, and glycocalyx degradation | Translational relevance uncertain |

| Goebel et al. [28] | 2023 | Human (crossover, n = 17) | 0 mg/mL e-cigarette (DIPSE-eGo, tobacco flavor) | ↑ Central BP, ↑ augmentation index, and ↑ small airway resistance in all groups, with more pronounced effects with nicotine | Small sample, single-center, acute effects only |

| Carnevale et al. [21] | 2016 | Human (crossover trial) | Acute exposure to traditional tobacco vs. NFEC exposure | NFECs and traditional tobacco show comparative decreases in vitamin E levels and flow-mediated dilation | Small sample, short-term |

| Franzen et al. [20] | 2018 | Human (clinical study) | Acute exposure to tobacco, NCEF, and NFECs in healthy adults | ↓ FMD in all groups; NFEC did not significantly alter BP or heart rate | Single-center, short-term |

| Chaumont et al. [27] | 2019 | Human (RCTs) | Fourth-generation EC exposure with and without nicotine | ↓ transcutaneous oxygen tension in all groups, ↓ arterial oxygen tension, and ↑ airway epithelial injury following EC aerosol at high wattage with and without nicotine | Small sample size |

| Caporale et al. [12] | 2019 | Human (MRI study) | Acute EC aerosol exposure | ↑ resistivity index, luminal FMD blunted, and reduced peak velocity; aortic pulse wave marginally increased | Healthy volunteers only |

| Papaioannou [24] | 2019 | Human (MRI study) | NFEC exposure | ↑ Aortic stiffness, as measured by aortic pulse wave velocity, and impaired endothelial function | Limited generalizability |

| Model/Study | Key Findings |

|---|---|

| Animal/embryonic studies | |

| Piechowski et al. (2021) [18] | Developmental cardiotoxicity in zebrafish embryos exposed to high-dose nicotine-free aerosols. |

| Espinoza-Derout et al. (2021) [23] | Systemic inflammation and vascular oxidative stress in mice after short-term exposure. |

| Dai et al. (2025) [25] | Mitochondrial dysfunction, ↑ ROS, and endothelial barrier disruption in murine and cell models. |

| Carnevale et al. (2016) [21] | ↑ Oxidative stress and endothelial dysfunction after acute exposure to nicotine-free aerosols. |

| Supporting evidence (not included in primary synthesis) | |

| Carll et al. (2022) [47] | Nicotine-free aerosol constituents induced atrial/ventricular arrhythmias, slow conduction, and repolarization defects in animal models. |

| Human studies | |

| Franzen et al. (2018) [20] | ↓ Flow-mediated dilation following nicotine-free vaping. |

| Chaumont et al. (2019) [27] | ↑ Arterial stiffness and systemic inflammation in RCT of nicotine-free exposure. |

| Caporale et al. (2019) [12] | MRI evidence of ↑ aortic stiffness after acute nicotine-free aerosol inhalation. |

| Papaioannou (2019) [24] | Transient ↑ aortic stiffness in healthy volunteers. |

| Goebel et al. (2023) [28] | ↑ Central BP, ↑ augmentation index, and ↑ small airway resistance, though less pronounced than with nicotine products. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jukic, I.; Becic, T.; Matulic, I.; Simac, P.; Vukovic, J. Impact of Nicotine-Free Electronic Cigarettes on Cardiovascular Health: A Systematic Review. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 8717. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14248717

Jukic I, Becic T, Matulic I, Simac P, Vukovic J. Impact of Nicotine-Free Electronic Cigarettes on Cardiovascular Health: A Systematic Review. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(24):8717. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14248717

Chicago/Turabian StyleJukic, Ivana, Tina Becic, Ivona Matulic, Petra Simac, and Jonatan Vukovic. 2025. "Impact of Nicotine-Free Electronic Cigarettes on Cardiovascular Health: A Systematic Review" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 24: 8717. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14248717

APA StyleJukic, I., Becic, T., Matulic, I., Simac, P., & Vukovic, J. (2025). Impact of Nicotine-Free Electronic Cigarettes on Cardiovascular Health: A Systematic Review. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(24), 8717. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14248717