NT-proBNP, Echocardiography Patterns and Outcomes in Sepsis-Induced Cardiac Dysfunction

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Definitions

2.3. Outcomes

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Baseline Characteristics

3.2. NT-proBNP

3.3. Troponin

3.4. Echocardiography

3.5. Outcomes

4. Discussion

Study Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Singer, M.; Deutschman, C.S.; Seymour, C.W.; Shankar-Hari, M.; Annane, D.; Bauer, M.; Bellomo, R.; Bernard, G.R.; Chiche, J.-D.; Coopersmith, C.M.; et al. The third international consensus definitions for sepsis and septic shock (sepsis-3). JAMA—J. Am. Med. Assoc. 2016, 315, 801–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martin, L.; Derwall, M.; Al Zoubi, S.; Zechendorf, E.; Reuter, D.A.; Thiemermann, C.; Schuerholz, T. The Septic Heart: Current Understanding of Molecular Mechanisms and Clinical Implications. Chest 2019, 155, 427–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paraschiv, C.; Popescu Moraru, M.R.; Paduraru, L.F.; Palcau, C.A.; Popescu, A.C.; Balanescu, S.M. Current challenges in understanding, diagnosing and managing sepsis-induced cardiac dysfunction. J. Crit. Care 2026, 91, 155250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shvilkina, T.; Shapiro, N. Sepsis-Induced myocardial dysfunction: Heterogeneity of functional effects and clinical significance. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2023, 10, 1200441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasegawa, D.; Ishisaka, Y.; Maeda, T.; Prasitlumkum, N.; Nishida, K.; Dugar, S.; Sato, R. Prevalence and Prognosis of Sepsis-Induced Cardiomyopathy: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Intensive Care Med. 2023, 38, 797–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanumanthu, B.K.J.; Nair, A.S.; Katamreddy, A.; Gilbert, J.S.; You, J.Y.; Offor, O.L.; Kushwaha, A.; Krishnan, A.; Napolitano, M.; Palaidimos, L.; et al. Sepsis-induced cardiomyopathy is associated with higher mortality rates in patients with sepsis. Acute Crit. Care 2021, 36, 215–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, R.; Kuriyama, A.; Takada, T.; Nasu, M.; Luthe, S.K. Prevalence and risk factors of sepsis-induced cardiomyopathy A retrospective cohort study. Medicine 2016, 95, e5031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, H.S.; Lee, T.H.; Bang, C.H.; Kim, J.H.; Hong, S.J. Risk factors and outcomes of sepsis-induced myocardial dysfunction and stress-induced cardiomyopathy in sepsis or septic shock. Medicine 2018, 97, e0263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Y.W.; Zhu, Y.F.; Zhang, R.; Ye, X.L.; Zhang, M.; Wei, J.R. Incidence, prognosis, and risk factors of sepsis-induced cardiomyopathy. World J. Clin. Cases 2021, 9, 9452–9468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paraschiv, C.; Nicolaescu, D.O.; Popescu, M.R.; Vasile, C.C.; Moisa, E.; Negoita, S.I.; Balanescu, S.M. Laboratory and Microbiological Considerations in Sepsis-Induced Cardiac Dysfunction. Medicina 2025, 61, 1765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kakoullis, L.; Giannopoulou, E.; Papachristodoulou, E.; Pantzaris, N.; Karamouzos, V.; Kounis, N.G.; Koniari, I.; Velissaris, D. The utility of brain natriuretic peptides in septic shock as markers for mortality and cardiac dysfunction: A systematic review. Int. J. Clin. Pract. 2019, 73, e13374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Merx, M.W.; Weber, C. Sepsis and the heart. Circulation 2007, 116, 793–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aissaoui, N.; Boissier, F.; Chew, M.; Singer, M.; Vignon, P. Sepsis-induced cardiomyopathy. Eur. Heart J. 2025, 46, 3339–3353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bergenzaun, L.; Gudmundsson, P.; Öhlin, H.; Düring, J.; Ersson, A.; Ihrman, L.; Willenheimer, R.; Chew, M.S. Assessing left ventricular systolic function in shock: Evaluation of echocardiographic parameters in intensive care. Crit. Care 2011, 15, R200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallabhajosyula, S.; Shankar, A.; Vojjini, R.; Cheungpasitporn, W.; Sundaragiri, P.R.; DuBrock, H.M.; Sekiguchi, H.; Frantz, R.P.; Cajigas, H.R.; Kane, G.C.; et al. Impact of Right Ventricular Dysfunction on Short-term and Long-term Mortality in Sepsis: A Meta-analysis of 1373 Patients. Chest 2021, 159, 2254–2263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanspa, M.J.; Pittman, J.E.; Hirshberg, E.L.; Wilson, E.L.; Olsen, T.; Brown, S.M.; Grissom, C.K. Association of left ventricular longitudinal strain with central venous oxygen saturation and serum lactate in patients with early severe sepsis and septic shock. Crit. Care 2015, 19, 304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurrell, D.G.; Nishimura, R.A.; Ilstrup, D.M.; Appleton, C.P. Utility of preload alteration in assessment of left ventricular filling pressure by Doppler echocardiography: A simultaneous catheterization and Doppler echocardiographic study. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 1997, 30, 459–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitter, S.S.; Shah, S.J.; Thomas, J.D. A Test in Context: E/A and E/e′ to Assess Diastolic Dysfunction and LV Filling Pressure. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2017, 69, 1451–1464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanfilippo, F.; Corredor, C.; Arcadipane, A.; Landesberg, G.; Vieillard-Baron, A.; Cecconi, M.; Fletcher, N. Tissue Doppler assessment of diastolic function and relationship with mortality in critically ill septic patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Br. J. Anaesth. 2017, 119, 583–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dias, S.P.; Brouwer, M.C.; Van De Beek, D. Sex and Gender Differences in Bacterial Infections. Infect. Immun. 2022, 90, e0028322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, S.L.M.; Muthoo, C.; Sanchez, J.; Del Arroyo, A.G.; Ackland, G.L. Sex-specific differences in cardiac function, inflammation and injury during early polymicrobial sepsis. Intensive Care Med. Exp. 2022, 10, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’brien, J.M.; Lu, B.; Ali, N.A.; Martin, G.S.; Aberegg, S.K.; Marsh, C.B.; Lemeshow, S.; Douglas, I.S. Alcohol dependence is independently associated with sepsis, septic shock, and hospital mortality among adult intensive care unit patients. Crit. Care Med. 2007, 35, 345–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moss, M.; Burnham, E.L. Alcohol abuse in the critically ill patient. Lancet 2006, 368, 2231–2242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Landesberg, G.; Gilon, D.; Meroz, Y.; Georgieva, M.; Levin, P.D.; Goodman, S.; Avidan, A.; Beeri, R.; Weissman, C.; Jaffe, A.S.; et al. Diastolic dysfunction and mortality in severe sepsis and septic shock. Eur. Heart J. 2012, 33, 895–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, S.M.; E Pittman, J.; Hirshberg, E.L.; Jones, J.P.; Lanspa, M.J.; Kuttler, K.G.; E Litwin, S.; Grissom, C.K. Diastolic dysfunction and mortality in early severe sepsis and septic shock: A prospective, observational echocardiography study. Crit. Ultrasound J. 2012, 4, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiraiwa, H.; Kasugai, D.; Ozaki, M.; Goto, Y.; Jingushi, N.; Higashi, M.; Nishida, K.; Kondo, T.; Furusawa, K.; Morimoto, R.; et al. Clinical impact of visually assessed right ventricular dysfunction in patients with septic shock. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 18823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.S.; Kim, Y.J.; Kim, M.; Ryoo, S.M.; Kim, W.Y. Association between right ventricle dysfunction and poor outcome in patients with septic shock. Heart 2020, 106, 1665–1671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonagh, T.A.; Metra, M.; Adamo, M.; Gardner, R.S.; Baumbach, A.; Böhm, M.; Burri, H.; Butler, J.; Čelutkienė, J.; Chioncel, O.; et al. 2021 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure. Eur. Heart J. 2021, 42, 3599–3726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonagh, T.A.; Metra, M.; Adamo, M.; Gardner, R.S.; Baumbach, A.; Böhm, M.; Burri, H.; Butler, J.; Čelutkienė, J.; Chioncel, O.; et al. 2023 Focused Update of the 2021 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure: Developed by the task force for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) With the special contribution of the Heart Failure Association (HFA) of the ESC. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 2024, 26, 5–17. [Google Scholar]

- Vassalli, F.; Masson, S.; Meessen, J.; Pasticci, I.; Bonifazi, M.; Vivona, L.; Caironi, P.; Busana, M.; Giosa, L.; Macrì, M.M.; et al. Pentraxin-3, Troponin T, N-Terminal Pro-B-Type Natriuretic Peptide in Septic Patients. Shock 2020, 54, 675–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masson, S.; Caironi, P.; Fanizza, C.; Carrer, S.; Caricato, A.; Fassini, P.; Vago, T.; Romero, M.; Tognoni, G.; Gattinoni, L.; et al. Sequential N-Terminal Pro-B-Type Natriuretic Peptide and High-Sensitivity Cardiac Troponin Measurements during Albumin Replacement in Patients with Severe Sepsis or Septic Shock. Crit. Care Med. 2016, 44, 707–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Januzzi, J.L.; Chen-Tournoux, A.A.; Christenson, R.H.; Doros, G.; Hollander, J.E.; Levy, P.D.; Nagurney, J.T.; Nowak, R.M.; Pang, P.S.; Patel, D.; et al. N-Terminal Pro–B-Type Natriuretic Peptide in the Emergency Department: The ICON-RELOADED Study. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2018, 71, 1191–1200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biswas, S.; Soneja, M.; Makkar, N.; Farooqui, F.A.; Roy, A.; Kumar, A.; Nischal, N.; Biswas, A.; Wig, N.; Sood, R.; et al. N-Terminal Pro-Brain Natriuretic Peptide is an Independent Predictor of Mortality in Patients with Sepsis. J. Investig. Med. 2022, 70, 369–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frencken, J.F.; Donker, D.W.; Spitoni, C.; E Koster-Brouwer, M.; Soliman, I.W.; Ong, D.S.Y.; Horn, J.; Van Der Poll, T.; A Van Klei, W.; Bonten, M.J.M.; et al. Myocardial Injury in Patients with Sepsis and Its Association with Long-Term Outcome. Circ. Cardiovasc. Qual. Outcomes 2018, 11, e004040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasile, V.C.; Chai, H.S.; Abdeldayem, D.; Afessa, B.; Jaffe, A.S. Elevated cardiac troponin T levels in critically ill patients with sepsis. Am. J. Med. 2013, 126, 1114–1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallabhajosyula, S.; Sakhuja, A.; Geske, J.B.; Kumar, M.; Poterucha, J.T.; Kashyap, R.; Kashani, K.; Jaffe, A.S.; Jentzer, J.C. Role of admission troponin-T and serial troponin-T testing in predicting outcomes in severe sepsis and septic shock. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2017, 6, e005930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Inclusion | Exclusion |

|---|---|

| Sepsis or septic shock as the main admission and discharge diagnosis | Cardiovascular:

|

| Age 18–89 years old | Oncological

|

| TTE in the first 48 h from admission Repeat TTE within 10 days if there is newly diagnosed LV dysfunction on first TTE | Preexistent end stage disease/ organ failure

|

| SICD (Total = 48) | Non-SICD (Total = 80) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years), median [IQR] | 74 [66.5, 82] | 71.5 [62.5, 80] | 0.248 |

| Male sex, number (%) | 25 (52) | 46 (57) | 0.551 |

| Smoker, number (%) | 12 (25) | 20 (25) | 1 |

| Alcohol abuse, number (%) | 11 (23) | 11 (14) | 0.183 |

| Hospital stay (days), median [IQR] | 12 [7, 19.5] | 10 [7, 18] | 0.752 |

| ICU stay (days), median [IQR] | 3.5 [1, 7] | 2 [1, 7] | 0.242 |

| SOFA on admission, median [IQR] | 7 [5, 9] | 6 [4, 9] | 0.470 |

| OTI on admission, number (%) | 14 (29) | 10 (12) | 0.019 |

| Vasopressor on admission, number (%) | 31 (65) | 33 (42) | 0.013 |

| In-hospital mortality, number (%) | 26 (54) | 30 (37) | 0.066 |

| Septic shock, number (%) | 36 (75) | 45 (56) | 0.033 |

| Healthcare-associated infection, number (%) | 18 (37) | 32 (40) | 0.779 |

| Positive cultures, number (%) | 37 (77) | 64 (80) | 0.695 |

Comorbidities

| 19 (40) 8 (17) 13 (27) 6 (12) 4 (8) 8 (17) 25 (52) 10 (21) | 35 (44) 12 (15) 32 (40) 10 (12) 5 (6) 17 (21) 35 (44) 24 (30) | 0.644 0.801 0.138 1 0.727 0.647 0.360 0.256 |

| Cardiac biomarkers Troponin I (ng/mL), median [IQR] NT-proBNP (pg/mL), median [IQR] | 0.16 [0.0, 0.71] 9022 [2465, 13,724] | 0.06 [0.0, 0.27] 4000 [3000, 10,100] | 0.368 0.172 |

| SICD: Isolated LV Systolic Dysfunction | SICD: Isolated RV Systolic Dysfunction | SICD: Biventricular Systolic Dysfunction | SICD: Isolated LV Diastolic Dysfunction | Non-SICD | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Definition | New and reversible drop in LVEF of at least 10% from baseline and under 50% | New and reversible drop in TAPSE of at least 2 mm from baseline and under 17 mm | LV and RV systolic dysfunction | New and reversible at least one of the following:

| Without cardiac dysfunction attributable to sepsis | |

| Number (%) (total = 128 patients) | 12 (9) | 9 (7) | 6 (5) | 21 (16) | 80 (63) | |

| Age, years, median (IQR) | 57 (49, 76) | 73 (67, 82) | 73.5 (65, 82) | 80 (73, 84) | 71.5 (62.5, 80) | 0.038 |

| Male (number/total) | 7/12 | 2/9 | 6/6 | 10/21 | 46/80 | 0.049 |

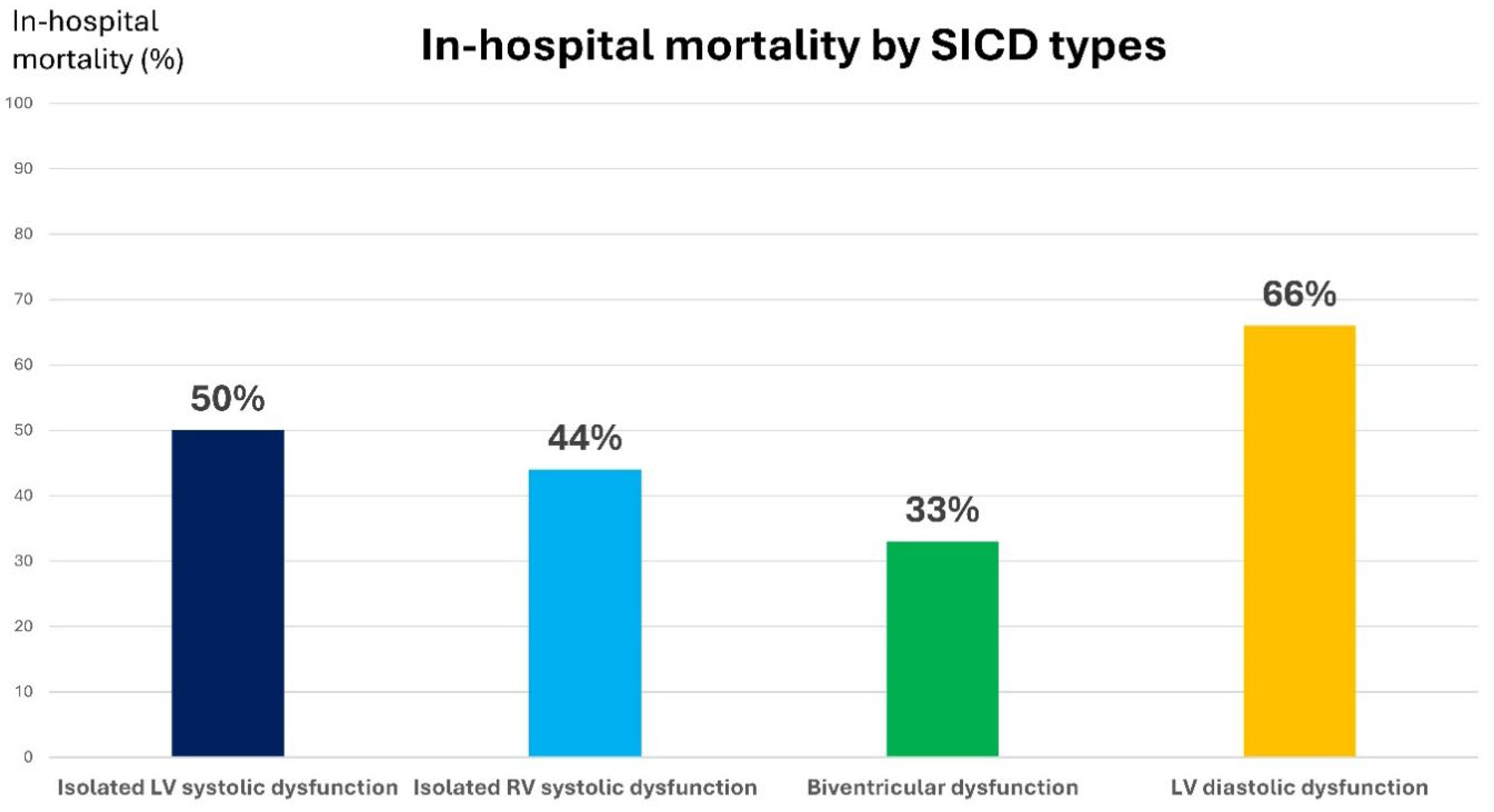

| In-hospital mortality (number/total) | 6/12 | 4/9 | 2/6 | 14/21 | 30/80 | 0.184 |

| SICD | Non-SICD | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| LVEF, median [IQR], % | 50 [41, 63] | 55 [53, 60] | 0.182 |

| VTI LVOT, median [IQR], cm | 17.2 [14.1, 21] | 19.5 [17.1, 22.5] | 0.070 |

| TAPSE, median [IQR], mm | 18 [16, 21] | 21 [18, 22] | 0.002 |

| RV s wave, median [IQR], cm/s | 11 [9.6, 12] | 12.7 [11.5, 14] | 0.002 |

| E, median, cm/s | 80 [60, 88] | 70 [52, 85] | 0.409 |

| E/A, median [IQR] | 1 [0.7, 1.5] | 0.7 [0.6, 1] | 0.081 |

| Lateral e’ wave, median [IQR], cm/s | 7 [5.6, 9.7] | 10.8 [8, 12.3] | 0.003 |

| Septal e’ wave, median [IQR], cm/s | 5 [4, 6.5] | 7 [5.1, 9.2] | 0.001 |

| E/lateral e’, median [IQR] | 10 [7.3, 12.9] | 6.3 [4.8, 8.5] | <0.001 |

| E/septal e’, median [IQR] | 12.8 [10.8, 17.1] | 9.3 [7.4, 10.9] | <0.001 |

| E/average e’, median [IQR] | 11.6 [8.6, 15] | 7.8 [5.9, 9.4] | <0.001 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Paraschiv, C.; Nicolaescu, D.O.; Popescu, R.M.; Barbalata, L.; Moisa, E.; Negoita, S.; Popescu, A.C.; Balanescu, S.M. NT-proBNP, Echocardiography Patterns and Outcomes in Sepsis-Induced Cardiac Dysfunction. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 8714. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14248714

Paraschiv C, Nicolaescu DO, Popescu RM, Barbalata L, Moisa E, Negoita S, Popescu AC, Balanescu SM. NT-proBNP, Echocardiography Patterns and Outcomes in Sepsis-Induced Cardiac Dysfunction. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(24):8714. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14248714

Chicago/Turabian StyleParaschiv, Catalina, Denisa Oana Nicolaescu, Roxana Mihaela Popescu, Laura Barbalata, Emanuel Moisa, Silvius Negoita, Andreea Catarina Popescu, and Serban Mihai Balanescu. 2025. "NT-proBNP, Echocardiography Patterns and Outcomes in Sepsis-Induced Cardiac Dysfunction" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 24: 8714. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14248714

APA StyleParaschiv, C., Nicolaescu, D. O., Popescu, R. M., Barbalata, L., Moisa, E., Negoita, S., Popescu, A. C., & Balanescu, S. M. (2025). NT-proBNP, Echocardiography Patterns and Outcomes in Sepsis-Induced Cardiac Dysfunction. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(24), 8714. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14248714