Clinical Outcomes of Minced Cartilage Treatment (AutoCart™) for Medial Osteochondral Lesions of the Talus: A Prospective One-Year Follow-Up Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Ethical Approval

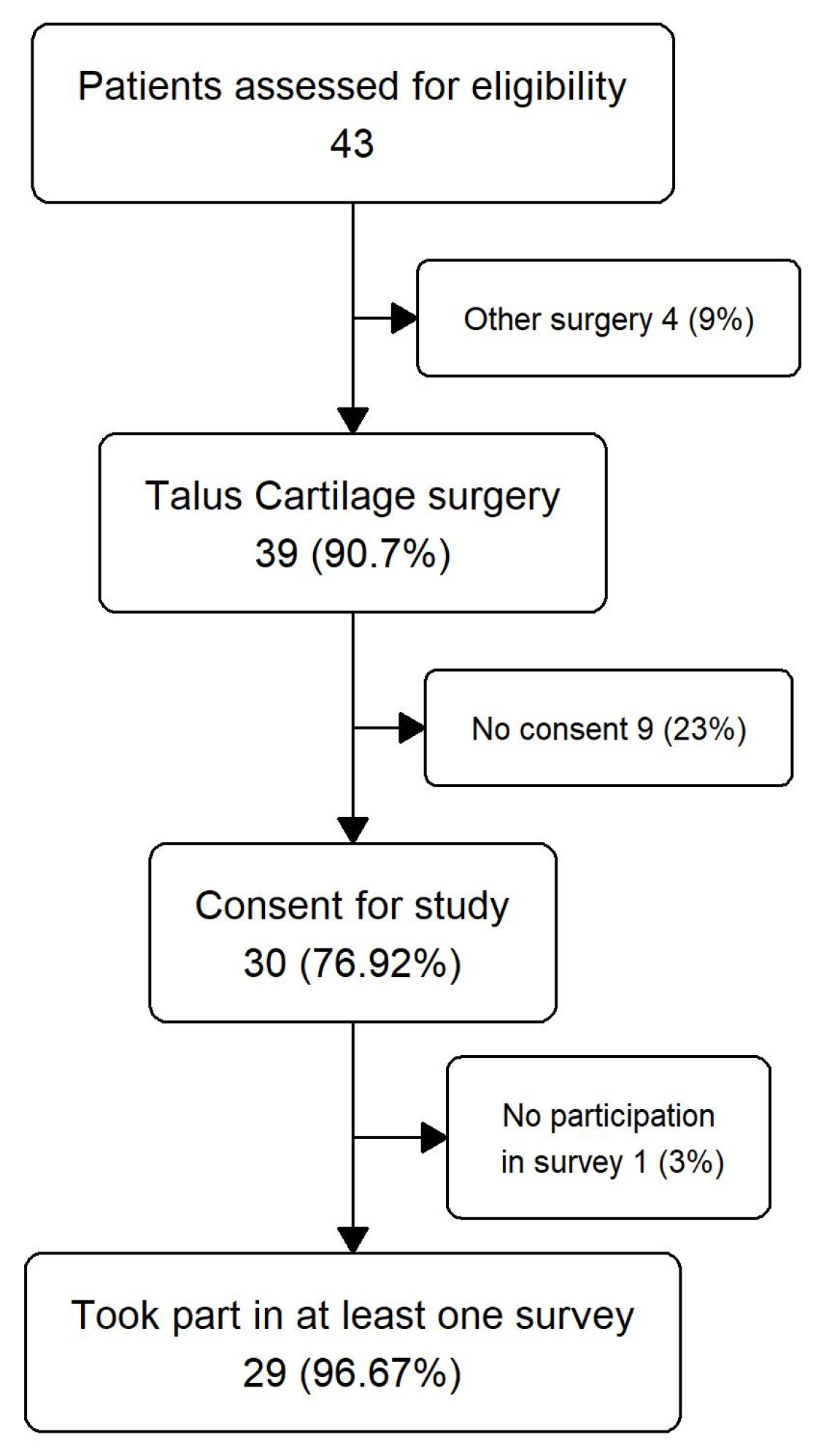

2.2. Cohort Selection

2.3. Radiological Assessment

2.4. Surgical Procedure

2.5. Modified Broström-Gould Procedure

2.6. Postoperative Management

2.7. Outcome Variables

2.8. Data Collection

2.9. Statistics

3. Results

3.1. Demographics and Patient Characteristics

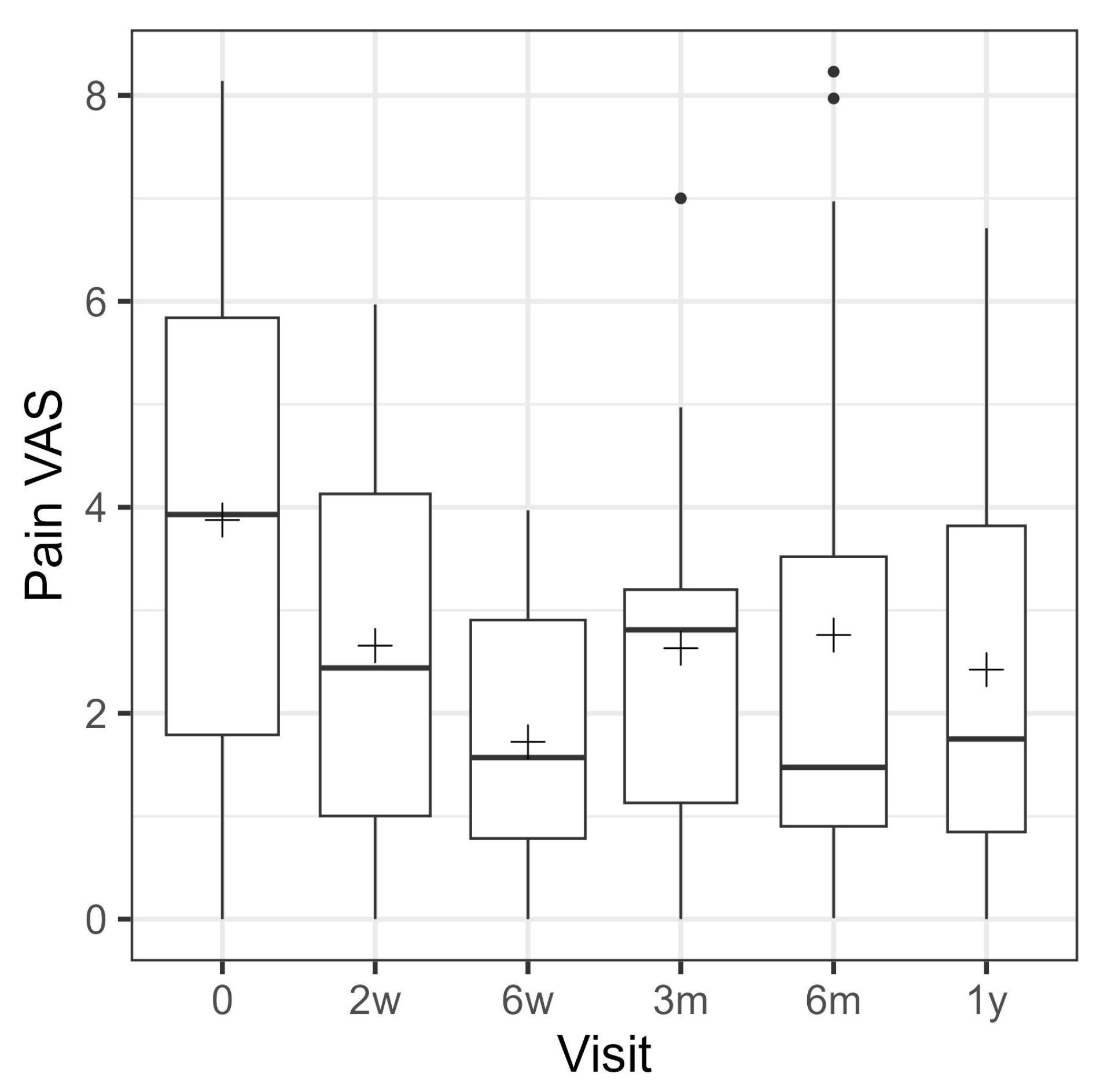

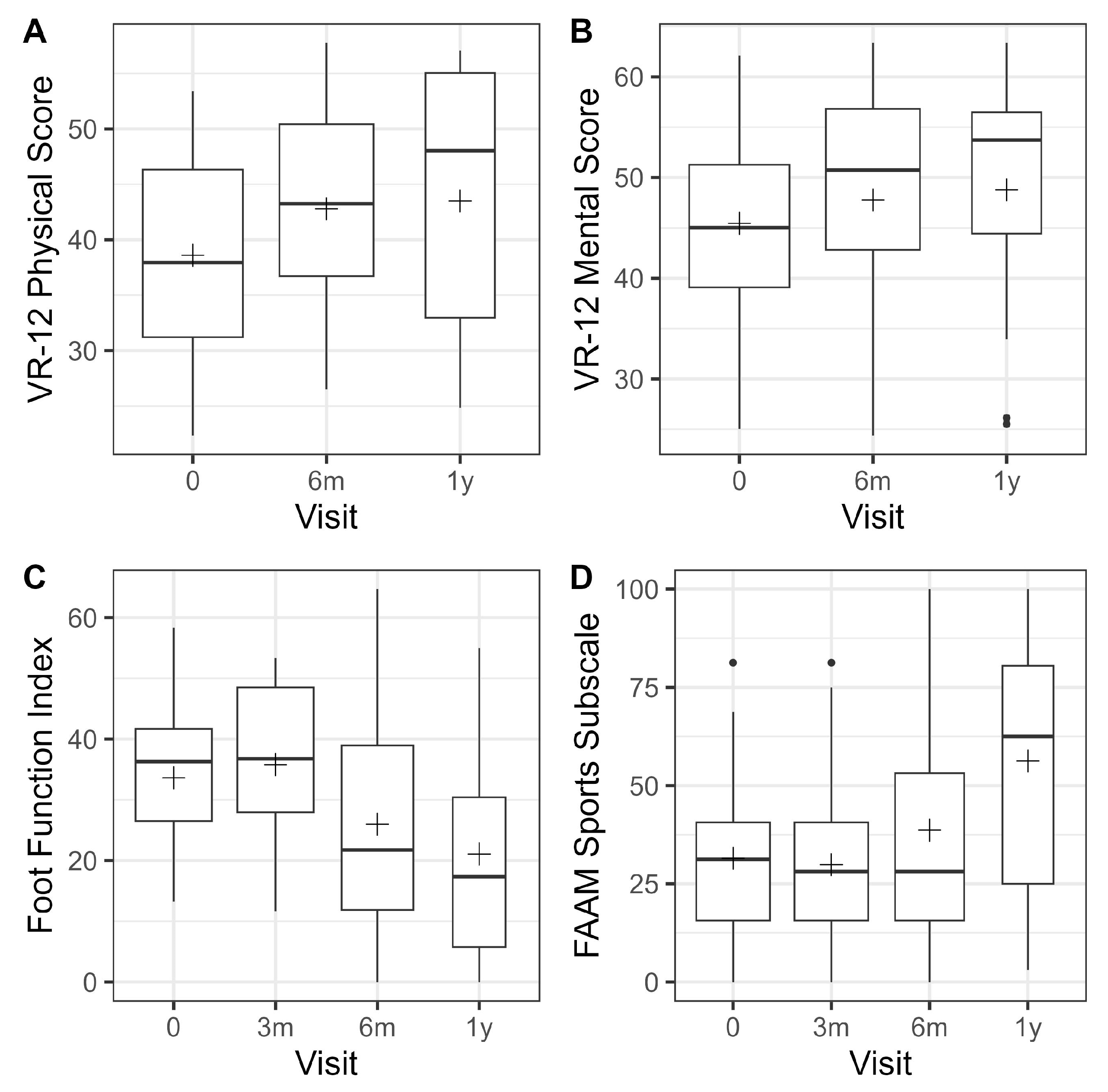

3.2. Patient-Reported Outcome Measures (PROMs)

4. Discussion

Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ACI | Autologous Chondrocyte Implantation |

| CT | Computer tomography |

| FAAM | Foot Ankle Ability Measure |

| FFI | Foot Function Index |

| MCI | Minced Cartilage Implatation |

| MRI | Magnete Resonance Imaging |

| OATs | Osteochondral autograft transplantation |

| SOS | Surgical Outcome System |

| VAS | Visual analogue scale |

| VR 12 | Veterans RAND 12-Item Health Survey |

References

- Hintermann, B.; Boss, A.; Schäfer, D. Arthroscopic Findings in Patients with Chronic Ankle Instability. Am. J. Sports Med. 2002, 30, 402–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karpiński, R.; Prus, A.; Baj, J.; Radej, S.; Prządka, M.; Krakowski, P.; Jonak, K. Articular Cartilage: Structure, Biomechanics, and the Potential of Conventional and Advanced Diagnostics. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 6896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerkhoffs, G.M.; Kennedy, J.G.; Calder, J.D.F.; Karlsson, J. There is no simple lateral ankle sprain. Knee Surg. Sports Traumatol. Arthrosc. 2016, 24, 941–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pueyo Moliner, A.; Ito, K.; Zaucke, F.; Kelly, D.J.; de Ruijter, M.; Malda, J. Restoring articular cartilage: Insights from structure, composition and development. Nat. Rev. Rheumatol. 2025, 21, 291–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, G.F.; Steele, J.R.; Fletcher, A.N.; Clement, R.D.; Arasa, M.A.; Adams, S.B. Fresh Osteochondral Allograft Transplantation for Osteochondral Lesions of the Talus: A Systematic Review. J. Foot Ankle Surg. 2021, 60, 585–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahmen, J.; Lambers, K.T.A.; Reilingh, M.L.; van Bergen, C.J.A.; Stufkens, S.A.S.; Kerkhoffs, G.M. No superior treatment for primary osteochondral defects of the talus. Knee Surg. Sports Traumatol. Arthrosc. 2018, 26, 2142–2157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zengerink, M.; Struijs, P.A.A.; Tol, J.L.; van Dijk, C.N. Treatment of osteochondral lesions of the talus: A systematic review. Knee Surg. Sports Traumatol. Arthrosc. 2010, 18, 238–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steele, J.R.; Dekker, T.J.; Federer, A.E.; Liles, J.L.; Adams, S.B.; Easley, M.E. Republication of “Osteochondral Lesions of the Talus: Current Concepts in Diagnosis and Treatment”. Foot Ankle Orthop. 2023, 8, 24730114231192961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimozono, Y.; Coale, M.; Yasui, Y.; O’hAlloran, A.; Deyer, T.W.; Kennedy, J.G. Subchondral Bone Degradation After Microfracture for Osteochondral Lesions of the Talus: An MRI Analysis. Am. J. Sports Med. 2018, 46, 642–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coetzee, J.C.; Giza, E.; Schon, L.C.; Berlet, G.C.; Neufeld, S.; Stone, R.M.; Wilson, E.L. Treatment of Osteochondral Lesions of the Talus With Particulated Juvenile Cartilage. Foot Ankle Int. 2013, 34, 1205–1211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salzmann, G.M.; Ossendorff, R.; Gilat, R.; Cole, B.J. Autologous Minced Cartilage Implantation for Treatment of Chondral and Osteochondral Lesions in the Knee Joint: An Overview. Cartilage 2021, 13 (Suppl. S1), 1124S–1136S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bogner, B.; Wenning, M.; Jungmann, P.M.; Reisert, M.; Lange, T.; Tennstedt, M.; Klein, L.; Diallo, T.D.; Bamberg, F.; Schmal, H.; et al. T1rho relaxation mapping in osteochondral lesions of the talus: A non-invasive biomarker for altered biomechanical properties of hyaline cartilage? Eur. Radiol. Exp. 2024, 8, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Diepen, P.R.; Smithuis, F.F.; Hollander, J.J.; Dahmen, J.; Emanuel, K.S.; Stufkens, S.A.; Kerkhoffs, G.M. Reporting of Morphology, Location, and Size in the Treatment of Osteochondral Lesions of the Talus in 11,785 Patients: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Cartilage 2024, 19476035241229026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spiegel, M.R. Mathematical Handbook of Formulas and Tables, 3rd ed.; Schaum’s Outline Series; McGraw-Hill Book Co.: New York, NY, USA, 2009; pp. 18–20. [Google Scholar]

- SooHoo, N.F.; Shuler, M.; Fleming, L.L. Evaluation of the validity of the AOFAS Clinical Rating Systems by correlation to the SF-36. Foot Ankle Int. 2003, 24, 50–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorbachova, T.; Melenevsky, Y.; Cohen, M.; Cerniglia, B.W. Osteochondral Lesions of the Knee: Differentiating the Most Common Entities at MRI. Radiographics 2018, 38, 1478–1495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hepple, S.; Winson, I.G.; Glew, D. Osteochondral lesions of the talus: A revised classification. Foot Ankle Int. 1999, 20, 789–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roth, K.E.; Ossendorff, R.; Klos, K.; Simons, P.; Drees, P.; Salzmann, G.M. Arthroscopic Minced Cartilage Implantation for Chondral Lesions at the Talus: A Technical Note. Arthrosc. Tech. 2021, 10, e1149–e1154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rilk, P.N.A.B.S. Patientenselektion und Indikationen zur operativen Knorpeltherapie. Knie J. 2025, 7, 11–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Dhanaraj, S.; Wang, Z.; Bradley, D.M.; Bowman, S.M.; Cole, B.J.; Binette, F. Minced cartilage without cell culture serves as an effective intraoperative cell source for cartilage repair. J. Orthop. Res. 2006, 24, 1261–1270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Jiang, Z.; Zou, X.; You, X.; Cai, Z.; Huang, J. Advancements in tissue engineering for articular cartilage regeneration. Heliyon 2024, 10, e25400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.H.; Park, K.H.; Cho, J.Y.; Han, S.H.; Lee, J.W. Bone Marrow Stimulation for Osteochondral Lesions of the Talus: Are Clinical Outcomes Maintained 10 Years Later? Am. J. Sports Med. 2021, 49, 1220–1226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuhle, J.; Wagner, F.C.; Beck, S.; Klein, L.; Bode, L.; Izadpanah, K.; Schmal, H.; Mühlenfeld, N. Autologous minced cartilage implantation in osteochondral lesions of the talus—Does fibrin make the difference? Arch. Orthop. Trauma. Surg. 2025, 145, 144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonasia, D.E.; Marmotti, A.; Mattia, S.; Cosentino, A.; Spolaore, S.; Governale, G.; Castoldi, F.; Rossi, R. The Degree of Chondral Fragmentation Affects Extracellular Matrix Production in Cartilage Autograft Implantation: An In Vitro Study. Arthrosc. J. Arthrosc. Relat. Surg. 2015, 31, 2335–2341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shim, D.W.; Hong, H.; Lee, J.W.; Kim, B.S. Particulated autologous cartilage transplantation for the treatment of osteochondral lesion of the talus: Can the lesion cartilage be recycled? Bone Jt. Open 2023, 4, 942–947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chuckpaiwong, B.; Berkson, E.M.; Theodore, G.H. Microfracture for Osteochondral Lesions of the Ankle: Outcome Analysis and Outcome Predictors of 105 Cases. Arthroscopy 2008, 24, 106–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giannini, S.; Buda, R.; Faldini, C.; Vannini, F.; Bevoni, R.; Grandi, G.; Grigolo, B.; Berti, L. Surgical treatment of osteochondral lesions of the talus in young active patients. J. Bone Joint Surg. Am. 2005, 87 (Suppl. S2), 28–41. [Google Scholar]

- Walther, M.; Gottschalk, O.; Aurich, M. Operative management of osteochondral lesions of the talus: 2024 recommendations of the working group ’clinical tissue regeneration’ of the German Society of Orthopedics and Traumatology (DGOU). EFORT Open Rev. 2024, 9, 217–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gottschalk, O.; Altenberger, S.; Baumbach, S.; Kriegelstein, S.; Dreyer, F.; Mehlhorn, A.; Hörterer, H.; Töpfer, A.; Röser, A.; Walther, M. Functional Medium-Term Results After Autologous Matrix-Induced Chondrogenesis for Osteochondral Lesions of the Talus: A 5-Year Prospective Cohort Study. J. Foot Ankle Surg. 2017, 56, 930–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walther, M. Scaffold Based Reconstruction of Focal Full Thickness Talar Cartilage Defects. Clin. Res. Foot Ankle 2013, 1, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubosch, E.J.; Erdle, B.; Izadpanah, K.; Kubosch, D.; Uhl, M.; Südkamp, N.P.; Niemeyer, P. Clinical outcome and T2 assessment following autologous matrix-induced chondrogenesis in osteochondral lesions of the talus. Int. Orthop. 2016, 40, 65–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Driscoll, S.W. The healing and regeneration of articular cartilage. J. Bone Joint Surg. Am. 1998, 80, 1795–1812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rikken, Q.G.H.; Kerkhoffs, G. Osteochondral Lesions of the Talus: An Individualized Treatment Paradigm from the Amsterdam Perspective. Foot Ankle Clin. 2021, 26, 121–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reilingh, M.L.; Lambers, K.T.A.; Dahmen, J.; Opdam, K.T.M.; Kerkhoffs, G.M.M.J. The subchondral bone healing after fixation of an osteochondral talar defect is superior in comparison with microfracture. Knee Surg. Sports Traumatol. Arthrosc. 2018, 26, 2177–2182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seow, D.; Shimozono, Y.; Gianakos, A.L.; Chiarello, E.; Mercer, N.; Hurley, E.T.; Kennedy, J.G. Autologous osteochondral transplantation for osteochondral lesions of the talus: High rate of return to play in the athletic population. Knee Surg. Sports Traumatol. Arthrosc. 2021, 29, 1554–1561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gottschalk, O.; Baumbach, S.F.; Altenberger, S.; Körner, D.; Aurich, M.; Plaass, C.; Ettinger, S.; Guenther, D.; Becher, C.; Hörterer, H.; et al. Influence of the Medial Malleolus Osteotomy on the Clinical Outcome of M-BMS + I/III Collagen Scaffold in Medial Talar Osteochondral Lesion (German Cartilage Register/Knorpelregister DGOU). Cartilage 2021, 13 (Suppl. S1), 1373S–1379S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Migliorini, F.; Maffulli, N.; Eschweiler, J.; Driessen, A.; Tingart, M.; Baroncini, A. Reliability of the MOCART score: A systematic review. J. Orthop. Traumatol. 2021, 22, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Körner, D.; Gonser, C.E.; Döbele, S.; Konrads, C.; Springer, F.; Keller, G. Re-operation rate after surgical treatment of osteochondral lesions of the talus in paediatric and adolescent patients. J. Orthop. Surg. Res. 2021, 16, 187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Inclusion Criteria | Exclusion Criteria |

|---|---|

| Age > 18 years Full-thickness chondral and osteochondral defects in the medial talar shoulder Symptoms (pain, loss of function) Conservative therapy-resistant course > 6 months Traumatic and non-traumatic lesions | Age < 18 years Rheumatic diseases Metabolic-associated cartilage damage (e.g., gout) Infection Body mass index > 34 kg/m2 Pregnancy Inability to comply with postoperative instructions Prior Surgeries of the ankle Revision procedures |

| Sex | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | F n = 14 1 | M n = 15 1 | p-Value 2 |

| Age at treatment | 0.7 | ||

| N Non-missing | 14 | 15 | |

| Mean (SD) | 35.3 (16.7) | 38.4 (16.3) | |

| Body height [cm] | 0.021 | ||

| N Non-missing | 12 | 11 | |

| Mean (SD) | 166.0 (10.5) | 175.4 (7.7) | |

| Body weight [kg] | 0.10 | ||

| N Non-missing | 12 | 11 | |

| Mean (SD) | 73.4 (16.1) | 85.7 (11.9) | |

| Body mass index (BMI) | 0.5 | ||

| N Non-missing | 12 | 11 | |

| Mean (SD) | 26.5 (4.8) | 27.9 (4.0) | |

| Body mass category | 0.9 | ||

| normal weight | 5 (42%) | 3 (27%) | |

| Overweight | 4 (33%) | 5 (45%) | |

| Obese | 3 (25%) | 3 (27%) | |

| Pre-treatment: Visual Analog Pain Scale: Visual Analog Pain Scale | 0.016 | ||

| N Non-missing | 12 | 13 | |

| Mean (SD) | 5.0 (2.2) | 2.8 (2.2) | |

| Pre-treatment: VR12: VR-12 Physical Score | 0.14 | ||

| Mean (SD) | 35.6 (8.2) | 41.4 (9.8) | |

| Pre-treatment: VR12: VR-12 Mental Score | >0.9 | ||

| Mean (SD) | 45.9 (7.6) | 45.1 (11.3) | |

| Pre-treatment: Foot Function Index: Foot Function Index | 0.9 | ||

| Mean (SD) | 34.6 (10.2) | 32.8 (13.2) | |

| Pre-treatment: FAAM—Sports Subscale: FAAM Sports Subscale | 0.4 | ||

| Mean (SD) | 28.6 (20.9) | 34.1 (20.3) | |

| Measuring Range | Result (n = 29) |

|---|---|

| Coronal diameter (mm) (Mean ± SD) | 9.07 ± 2.01 |

| Sagital diameter (mm) (mean ± SD) | 13.67 ± 3.94 |

| Vertical depth (mm) (mean ± SD) | 7.73 ± 1.03 |

| Area (mm2) (mean ± SD) | 121.95 ± 54.46 |

| <100 mm2 | 2 |

| ≥100 mm2 | 27 |

| Item | Number (n = 29) |

|---|---|

| Malleolar osteotomy | 26 |

| Purely arthroscopic | 3 |

| Concomitant ligament reconstruction | 16 |

| Bone plasty | 26 |

| Visual Analog Pain Scale | VR-12 Physical Score | VR-12 Mental Score | Foot Function Index | FAAM—Sports Subscale | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time | n | Mean | 95% CI | p-Value | Mean | 95% CI | p-Value | Mean | 95% CI | p-Value | Mean | 95% CI | p-Value | Mean | 95% CI | p-Value |

| 2 w | 24 | −1.2 | [−2.2; −0.2] | 0.0153 | ||||||||||||

| 6 w | 26 | −2.2 | [−3.2; −1.3] | <0.0001 | ||||||||||||

| 3 m | 25 | −1.3 | [−2.3; −0.3] | 0.0110 | 1.3 | [−4.6; 7.3] | 0.6545 | −1.6 | [−10.6; 7.4] | 0.7168 | ||||||

| 6 m | 22 | −1.2 | [−2.3; −0.2] | 0.0177 | 4.5 | [−0.5; 9.5] | 0.0777 | 4.2 | [−0.5; 8.9] | 0.0801 | −9.1 | [−15.4; −2.7] | 0.0057 | 6.8 | [−2.7; 16.4] | 0.1551 |

| 1 y | 12 | −1.3 | [−2.6; −0.1] | 0.0357 | 5.2 | [−0.9; 11.3] | 0.0904 | 4.8 | [−1.0; 10.5] | 0.1000 | −13.3 | [−21.0; −5.6] | 0.0011 | 18.6 | [7.0; 30.1] | 0.0021 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Roth, K.E.; Salzmann, G.M.; Winter, P.; Schmidtmann, I.; Maier, G.; Cochrane, I.; Ossendorff, R.; Klos, K.; Drees, P. Clinical Outcomes of Minced Cartilage Treatment (AutoCart™) for Medial Osteochondral Lesions of the Talus: A Prospective One-Year Follow-Up Study. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 8710. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14248710

Roth KE, Salzmann GM, Winter P, Schmidtmann I, Maier G, Cochrane I, Ossendorff R, Klos K, Drees P. Clinical Outcomes of Minced Cartilage Treatment (AutoCart™) for Medial Osteochondral Lesions of the Talus: A Prospective One-Year Follow-Up Study. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(24):8710. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14248710

Chicago/Turabian StyleRoth, Klaus E., Gian M. Salzmann, Philipp Winter, Irene Schmidtmann, Gerrit Maier, Isabelle Cochrane, Robert Ossendorff, Kajetan Klos, and Philipp Drees. 2025. "Clinical Outcomes of Minced Cartilage Treatment (AutoCart™) for Medial Osteochondral Lesions of the Talus: A Prospective One-Year Follow-Up Study" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 24: 8710. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14248710

APA StyleRoth, K. E., Salzmann, G. M., Winter, P., Schmidtmann, I., Maier, G., Cochrane, I., Ossendorff, R., Klos, K., & Drees, P. (2025). Clinical Outcomes of Minced Cartilage Treatment (AutoCart™) for Medial Osteochondral Lesions of the Talus: A Prospective One-Year Follow-Up Study. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(24), 8710. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14248710