Trigger Factors in Recurrent Corneal Erosion Syndrome

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

Statistics

3. Results

3.1. Baseline Characteristics and Triggering Factors in Patients with RCES

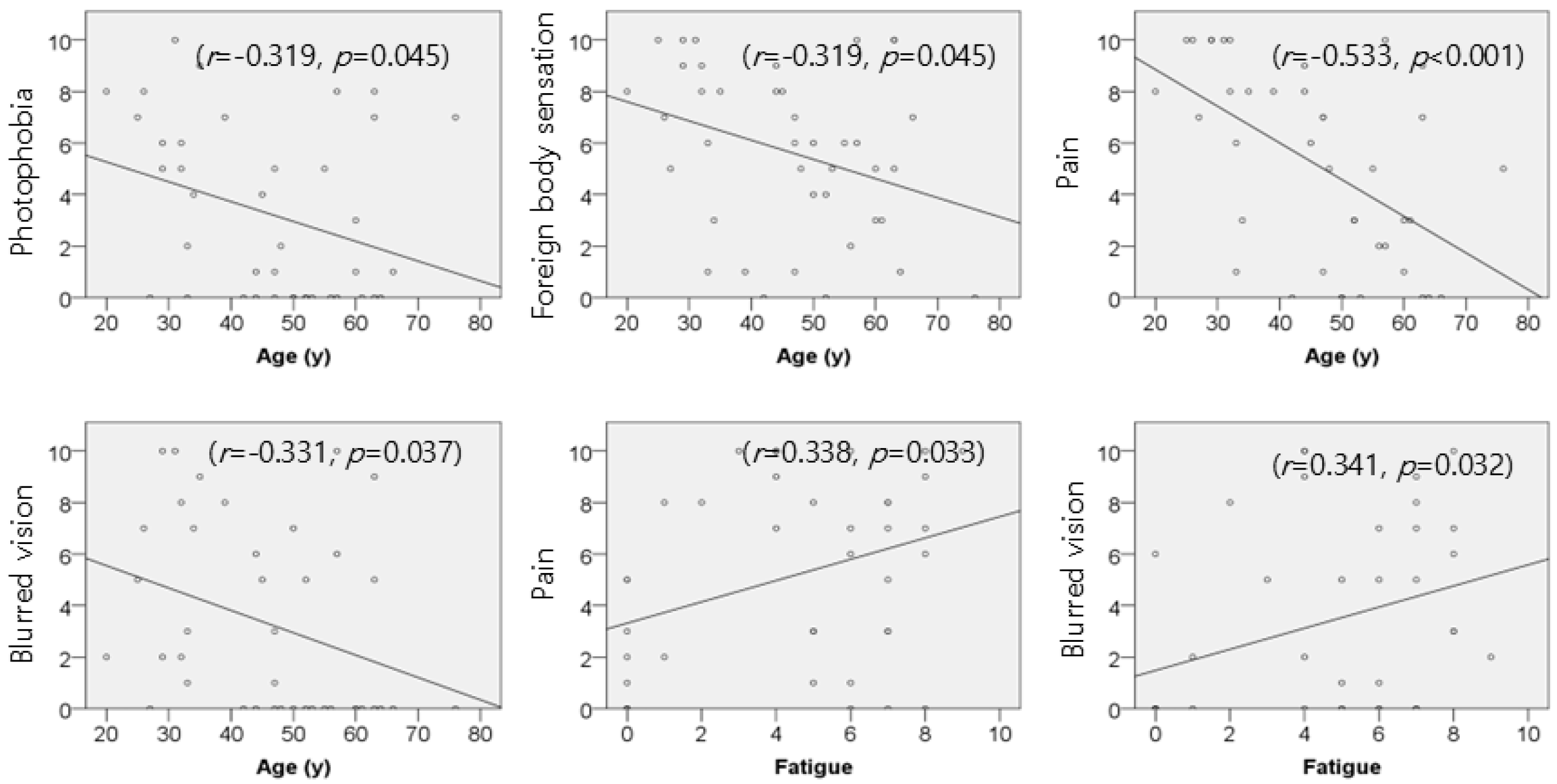

3.2. Association of Age and Fatigue with Symptom Severity in RCES

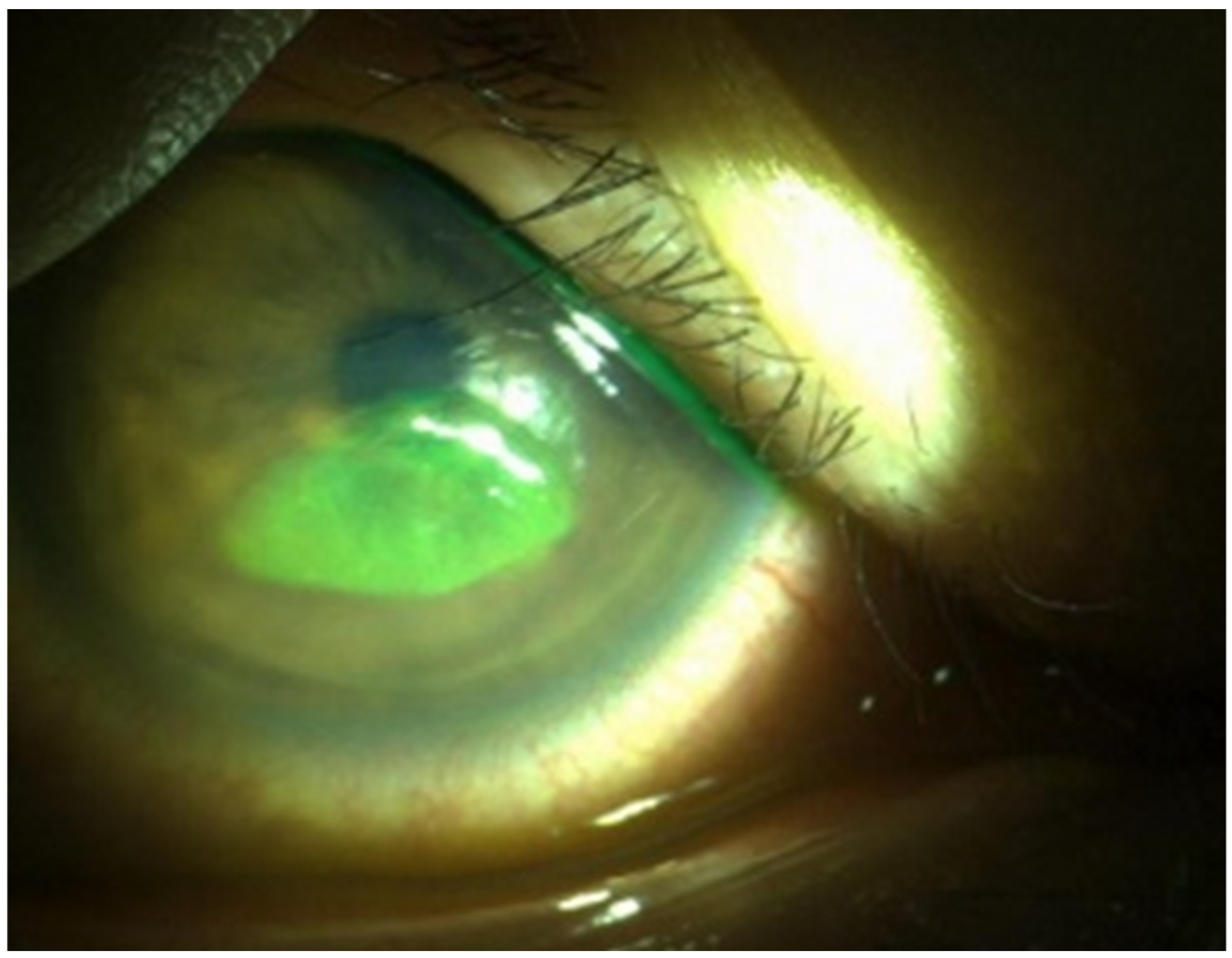

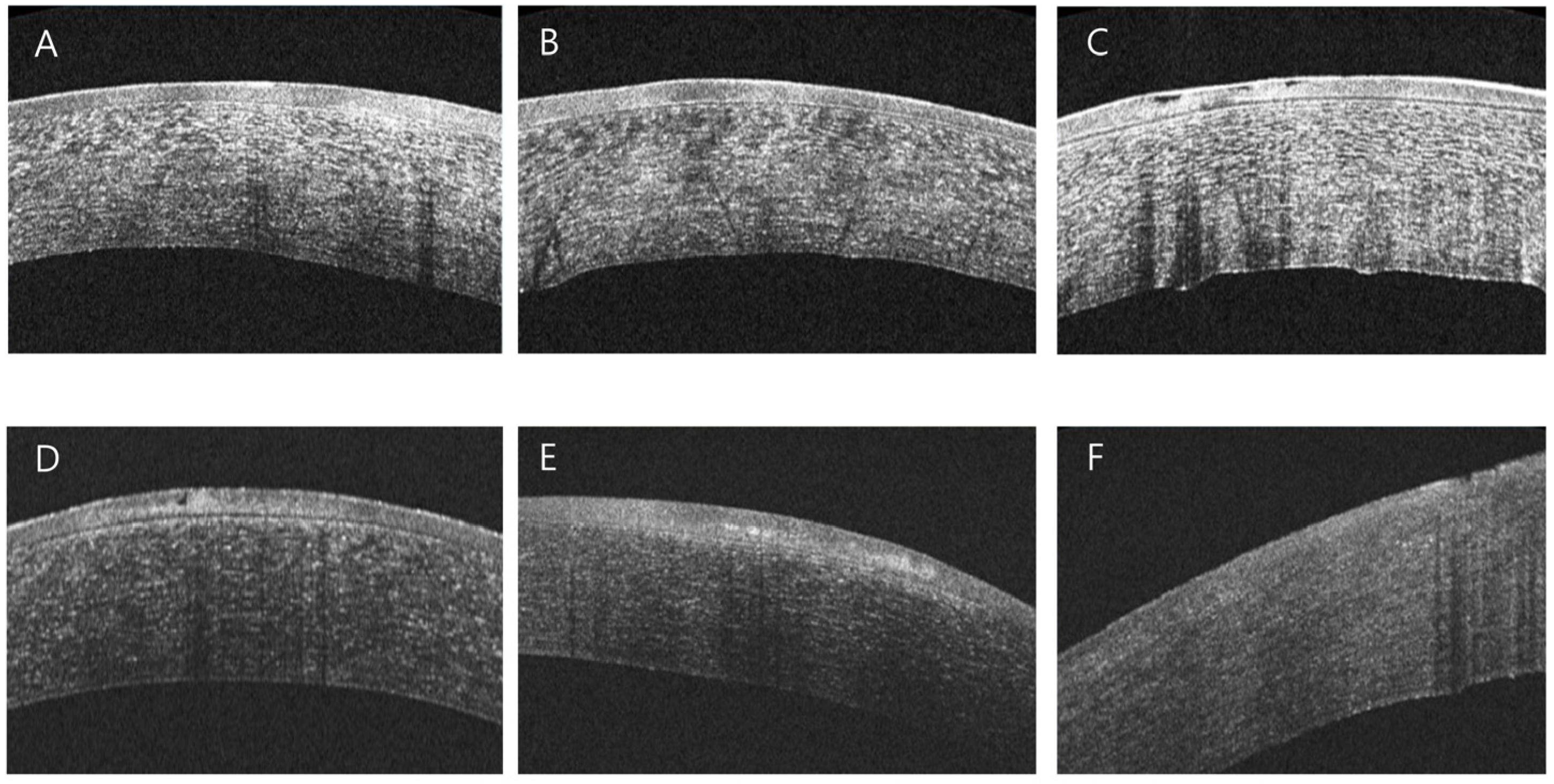

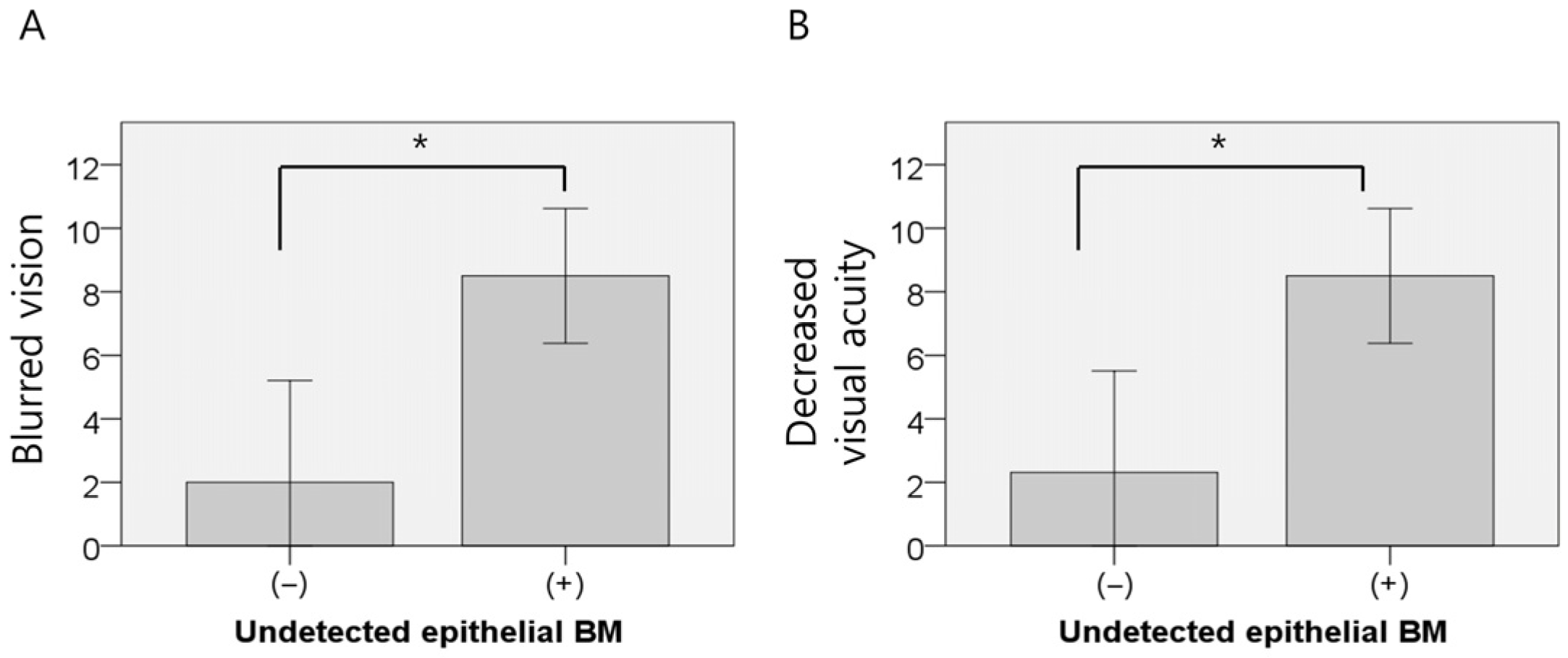

3.3. AS-OCT-Based Analysis of Corneal Structural Changes in RCES

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

6. Patents

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AS-OCT | Anterior Segment Optical Coherence Tomography |

| BM | Basement Membrane |

| RCES | Recurrent Corneal Erosion Syndrome |

References

- Miller, D.D.; Hasan, S.A.; Simmons, N.L.; Stewart, M.W. Recurrent corneal erosion: A comprehensive review. Clin. Ophthalmol. 2019, 13, 325–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni Mhealoid, A.; Lukasik, T.; Power, W.; Murphy, C.C. Alcohol delamination of the corneal epithelium for recurrent corneal erosion syndrome. Int. J. Ophthalmol. 2018, 11, 1129–1131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nanba, H.; Mimura, T.; Mizuno, Y.; Matsumoto, K.; Hamano, S.; Ubukata, S.; Yamamoto, M.; Watanabe, E.; Mizota, A. Clinical course and risk factors of recurrent corneal erosion: Observational study. Medicine 2019, 98, e14964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reeves, S.W.; Kang, P.C.; Zlogar, D.F.; Gupta, P.K.; Stinnett, S.; Afshari, N.A. Recurrent Corneal Erosion Syndrome: A Study of 364 Episodes. Ophthalmic Surg. Lasers Imaging 2010, 41, 1–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ewald, M.; Hammersmith, K.M. Review of diagnosis and management of recurrent erosion syndrome. Curr. Opin. Ophthalmol. 2009, 20, 287–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diez-Feijoo, E.; Duran, J.A. Optical coherence tomography findings in recurrent corneal erosion syndrome. Cornea 2015, 34, 290–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, W.; Reinstein, D.Z.; Archer, T.J.; Chen, X.; Utheim, T.P.; Feng, Y.; Stojanovic, A. Intraoperative Swept-Source OCT-Based Corneal Topography for Measurement and Analysis of Stromal Surface After Epithelial Removal. J. Refract. Surg. 2021, 37, 484–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maclure, M. The case-crossover design: A method for studying transient effects on the risk of acute events. Am. J. Epidemiol. 1991, 133, 144–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewer, D.; Petersen, I.; Maclure, M. The case-crossover design for studying sudden events. BMJ Med. 2022, 1, e000214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corrao, G.; Mancia, G. Generating evidence from computerized healthcare utilization databases. Hypertension 2015, 65, 490–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, S.T.; Chen, C.C.; Tsang, H.Y.; Lee, C.S.; Yang, P.; Cheng, K.D.; Li, D.J.; Wang, C.J.; Hsieh, Y.C.; Yang, W.C. Association between antipsychotic use and risk of acute myocardial infarction: A nationwide case-crossover study. Circulation 2014, 130, 235–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grimes, D.A.; Schulz, K.F. Bias and causal associations in observational research. Lancet 2002, 359, 248–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omari, A.A.; Mian, S.I. Recurrent Corneal Erosions in Corneal Dystrophies: A Review of the Pathogenesis, Differential Diagnosis, and Therapy. Klin. Monbl. Augenheilkd. 2018, 235, 689–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, S.; Seitz, B. Recurrent corneal erosion syndrome. Surv. Ophthalmol. 2008, 53, 3–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramamurthi, S.; Rahman, M.Q.; Dutton, G.N.; Ramaesh, K. Pathogenesis, clinical features and management of recurrent corneal erosions. Eye 2006, 20, 635–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.E.; Kim, D.B. Cataract incision-related corneal erosion: Recurrent corneal erosion because of clear corneal cataract surgery. J. Cataract. Refract. Surg. 2020, 46, 1436–1440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.H.; Kim, J.H.; Nam, W.H.; Yi, K.; Choi, D.G.; Hyon, J.Y.; Wee, W.R.; Shin, Y.J. Oral alcohol administration disturbs tear film and ocular surface. Ophthalmology 2012, 119, 965–971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karimi, S.; Arabi, A.; Shahraki, T. Alcohol and the Eye. J. Ophthalmic Vis. Res. 2021, 16, 260–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peart, D.J.; Walshe, I.H.; Sweeney, E.L.; James, E.; Henderson, T.; O’Doherty, A.F.; McDermott, A.M. The effect of acute exercise on environmentally induced symptoms of dry eye. Physiol. Rep. 2020, 8, e14262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, K.; Tominaga, T.; Ruhee, R.T.; Ma, S. Characterization and Modulation of Systemic Inflammatory Response to Exhaustive Exercise in Relation to Oxidative Stress. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.; Dai, W.; Lu, L. Hyperosmotic stress-induced corneal epithelial cell death through activation of Polo-like kinase 3 and c-Jun. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2011, 52, 3200–3206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Dai, W.; Lu, L. Osmotic stress-induced phosphorylation of H2AX by polo-like kinase 3 affects cell cycle progression in human corneal epithelial cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2014, 289, 29827–29835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dolivo, D.; Rodrigues, A.; Sun, L.; Galiano, R.; Mustoe, T.; Hong, S.J. Reduced hydration regulates pro-inflammatory cytokines via CD14 in barrier function-impaired skin. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Basis Dis. 2022, 1868, 166482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohidin, N.; Jaafar, A.B. Effect of Smoking on Tear Stability and Corneal Surface. J. Curr. Ophthalmol. 2020, 32, 232–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, E.Y.; Chen, H.T.; Hsueh, Y.J.; Chen, H.C.; Tan, H.Y.; Hsiao, C.H.; Yeh, L.K.; Wu, W.C. Corneal Sensitivity and Tear Function in Recurrent Corneal Erosion Syndrome. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2020, 61, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Dujaili, L.J.; Clerkin, P.P.; Clement, C.; McFerrin, H.E.; Bhattacharjee, P.S.; Varnell, E.D.; Kaufman, H.E.; Hill, J.M. Ocular herpes simplex virus: How are latency, reactivation, recurrent disease and therapy interrelated? Future Microbiol. 2011, 6, 877–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheppard, J.D.; Nichols, K.K. Dry Eye Disease Associated with Meibomian Gland Dysfunction: Focus on Tear Film Characteristics and the Therapeutic Landscape. Ophthalmol. Ther. 2023, 12, 1397–1418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hykin, P.G.; Foss, A.E.; Pavesio, C.; Dart, J.K. The natural history and management of recurrent corneal erosion: A prospective randomised trial. Eye 1994, 8 Pt 1, 35–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fedak, K.M.; Bernal, A.; Capshaw, Z.A.; Gross, S. Applying the Bradford Hill criteria in the 21st century: How data integration has changed causal inference in molecular epidemiology. Emerg. Themes Epidemiol. 2015, 12, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, D.P.; Smitherman, T.A.; Martin, V.T.; Penzien, D.B.; Houle, T.T. Causality and headache triggers. Headache 2013, 53, 628–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chin, J.Y.; Liu, C.; Lee, I.X.Y.; Lin, M.T.Y.; Cheng, C.Y.; Wong, J.H.F.; Teo, C.L.; Mehta, J.S.; Liu, Y.C. Impact of Age on the Characteristics of Corneal Nerves and Corneal Epithelial Cells in Healthy Adults. Cornea 2024, 43, 409–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chirapapaisan, C.; Thongsuwan, S.; Chirapapaisan, N.; Chonpimai, P.; Veeraburinon, A. Characteristics of Corneal Subbasal Nerves in Different Age Groups: An in vivo Confocal Microscopic Analysis. Clin. Ophthalmol. 2021, 15, 3563–3572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, P.J.; Patel, S.; Kong, N.; Ryder, R.E.; Marshall, J. Noninvasive assessment of corneal sensitivity in young and elderly diabetic and nondiabetic subjects. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2004, 45, 1737–1742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Tumi, H.; Johnson, M.I.; Dantas, P.B.F.; Maynard, M.J.; Tashani, O.A. Age-related changes in pain sensitivity in healthy humans: A systematic review with meta-analysis. Eur. J. Pain 2017, 21, 955–964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, S.R.; Aldave, A.J.; Chodosh, J. Recurrent corneal erosion syndrome. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 2019, 103, 1204–1208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seamans, M.J.; Hong, H.; Ackerman, B.; Schmid, I.; Stuart, E.A. Generalizability of Subgroup Effects. Epidemiology 2021, 32, 389–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bender, R.; Lange, S. Adjusting for multiple testing--when and how? J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2001, 54, 343–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rothman, K.J. No adjustments are needed for multiple comparisons. Epidemiology 1990, 1, 43–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BaHammam, A.S. NHANES Sleep Research as a Cautionary Tale: When Big Data Goes Wrong. Nat. Sci. Sleep 2025, 17, 2799–2805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pogoda-Wesolowska, A.; Stachura, I.; Slugocka, N.; Kania-Pudlo, M.; Staszewski, J.; Stepien, A. Amygdala volume changes as a potential marker of multiple sclerosis progression: Links to EDSS scores and PIRA. Front. Immunol. 2025, 16, 1640607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malheiro, A.; Forte, P.; Rodriguez Rosell, D.; Marques, D.L.; Marques, M.C. Exploratory Analysis of the Correlations Between Physiological and Biomechanical Variables and Performance in the CrossFit((R)) Fran Benchmark Workout. J. Funct. Morphol. Kinesiol. 2025, 10, 387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lee, G.M.; Gwon, H.N.; Shin, Y.J. Trigger Factors in Recurrent Corneal Erosion Syndrome. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 8694. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14248694

Lee GM, Gwon HN, Shin YJ. Trigger Factors in Recurrent Corneal Erosion Syndrome. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(24):8694. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14248694

Chicago/Turabian StyleLee, Gyeong Min, Hae Nah Gwon, and Young Joo Shin. 2025. "Trigger Factors in Recurrent Corneal Erosion Syndrome" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 24: 8694. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14248694

APA StyleLee, G. M., Gwon, H. N., & Shin, Y. J. (2025). Trigger Factors in Recurrent Corneal Erosion Syndrome. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(24), 8694. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14248694