Inter-Observer Agreement and Laboratory Correlation of the 4T Scoring Model for Heparin-Induced Thrombocytopenia: A Single-Center Retrospective Study and Literature Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

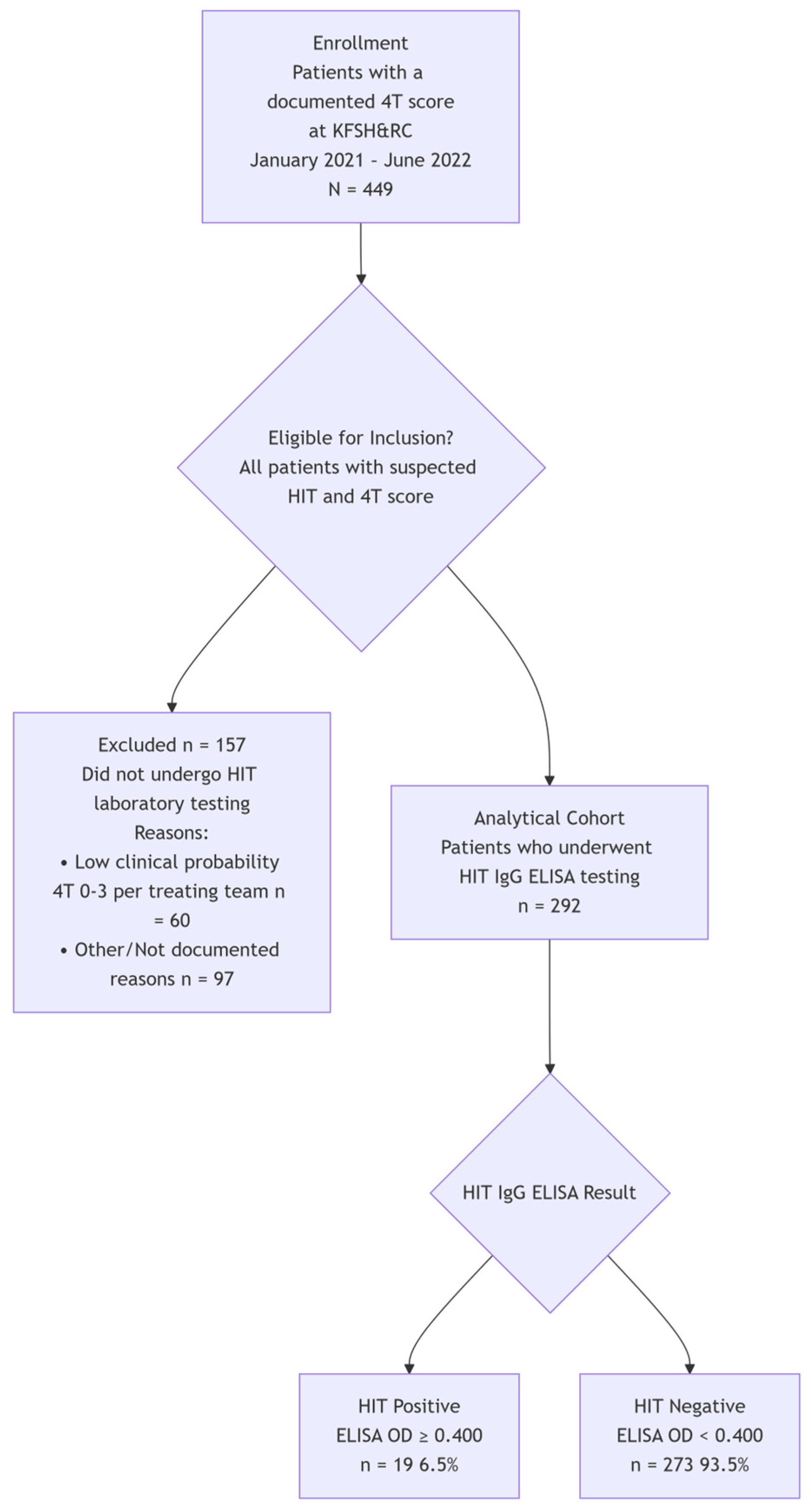

2.1. Patients and Study Design

2.2. Measurements

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Demographics and Patient Characteristics

3.2. Comparison of Calculated 4T Scores and Agreement

3.3. Positive HIT Diagnoses and 4T Scores

3.4. Comparison of Calculated 4T Scores and Potential Missed Cases

Positive HIT Diagnoses and 4T Scores

3.5. Heparin Type and HIT

4. Discussion

4.1. Overview and Applications

4.2. Effectiveness, Limitations, and Clinical Management for HIT

5. Study Limitations and Challenges

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hvas, A.-M.; Favaloro, E.J.; Hellfritzsch, M. Heparin-induced thrombocytopenia: Pathophys-iology, diagnosis and treatment. Expert Rev. Hematol. 2021, 14, 335–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cuker, A.; Gimotty, P.A.; Crowther, M.A.; Warkentin, T.E. Predictive value of the 4Ts scor-ing system for heparin-induced thrombocytopenia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Blood 2012, 120, 4160–4167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arepally, G.M. Heparin-induced thrombocytopenia. Blood 2017, 129, 2864–2872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Junqueira, D.R.; Zorzela, L.M.; Perini, E. Unfractionated heparin versus low molecular weight heparins for avoiding heparin-induced thrombocytopenia in postoperative patients. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2017, 2017, CD007557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Linkins, L.-A.; Dans, A.L.; Moores, L.K.; Bona, R.; Davidson, B.L.; Schulman, S.; Crowther, M. Treatment and Prevention of Heparin-Induced Thrombocytopenia. Chest 2012, 141, e495S–e530S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- May, J.; Westbrook, B.; Cuker, A. Heparin-induced thrombocytopenia: An illustrated review. Res. Pract. Thromb. Haemost. 2023, 7, 100283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- May, J.; Cuker, A. Practical guide to the diagnosis and management of heparin-induced thrombocytopenia. Hematology 2024, 2024, 388–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Attah, A.; Peterson, C.; Jacobs, M.; Bhagavatula, R.; Shah, D.; Kaplan, R.; Samhouri, Y. Anti-PF4 ELISA-Negative, SRA-Positive Heparin-Induced Thrombocytopenia. Hematol. Rep. 2024, 16, 295–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kelly, J.; Sylvester, K.W.; Rimsans, J.; Bernier, T.D.; Ting, C.; Connors, J.M. Heparin-induced thrombocytopenia in end-stage renal disease: Reliability of the PF4-heparin ELISA. Res. Pract. Thromb. Haemost. 2021, 5, e12573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sahu, K.K.; Jindal, V.; Anderson, J.; Siddiqui, A.D.; Jaiyesimi, I.A. Current Perspectives on Diagnostic Assays and Anti-PF4 Antibodies for the Diagnosis of Heparin-Induced Thrombocytopenia. J. Blood Med. 2020, 11, 267–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crowther, M.A.; Cook, D.J.; Albert, M.; Williamson, D.; Meade, M.; Granton, J.; Skrobik, Y.; Lange-vin, S.; Mehta, S.; Hebert, P.; et al. The 4Ts scoring system for heparin-induced thrombocytopenia in medical-surgical intensive care unit patients. J. Crit. Care 2010, 25, 287–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rice, L. HITs and misses in 100 years of heparin. Hematology 2017, 2017, 667–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Otis, S.A.; Zehnder, J.L. Heparin-induced thrombocytopenia: Current status and diagnostic challenges. Am. J. Hematol. 2010, 85, 700–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Warkentin, T.E.; Greinacher, A.; Koster, A.; Lincoff, A.M. Treatment and Prevention of Heparin-Induced Thrombocytopenia. Chest 2008, 133, 340S–380S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| 2 Points | 1 Point | 0 Point | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Thrombocytopenia | PLT decrease >50% AND nadir ≥ 20,000/µL AND no surgery within preceding 3 days | PLT decrease > 50% BUT surgery within preceding 3 days OR any combination of PLT fall and nadir that does not fit criteria for 2 or 0 points (eg, 30 to 50% fall or nadir 10,000 to 19,000/µL) | PLT decrease < 30% OR nadir < 10,000/µL |

| Timing of onset after heparin exposure | 5 to 10 days OR 1 day if exposure within past 5 to 30 days | Probable 5 to 10 days (eg, missing PLT counts) OR > 10 days OR < 1 day if exposure within past 31 to 100 days | <4 days without exposure within past 100 days |

| Thrombosis or other clinical sequelae | Confirmed new thrombosis, skin necrosis, anaphylactoid reaction, or adrenal hemorrhage | Suspected, progressive, or recurrent thrombosis, skin erythema | None |

| Other causes for thrombocytopenia | None | Possible (eg, sepsis) | Probable (eg, DIC, medication, within 72 h of surgery) |

| Interpretation | |||

| 0 to 3 points—Low probability (<1%) 4 to 5 points—Intermediate probability (approximately 10%) 6 to 8 points—High probability (approximately 50%) | |||

| Gender (%) | ||

| Males | 151 (51.7) | |

| Females | 141 (48.3) | |

| Heparin type (%) | ||

| Unfractionated heparin | 280 (95.9) | |

| Low molecular weight heparin | 12 (4.1) | |

| Clinical Characteristics | ||

| HIT results | Positive | Negative |

| Age, mean (SD) | 53.2 (17.3) | 56.6 (19.6) |

| HIT OD, mean (SD) | 1.20 (0.72) | 0.13 (0.06) |

| Platelet count at time of diagnosis, mean (SD) | 61.6 (41.2) | 73.6 (52.4) |

| Normal platelet count (%) | 1 (0.3) | 19 (6.5) |

| Thrombocytopenia (%) | 18 (6.2) | 254 (87) |

| 4T by Trained physicians | ||

| 0–3 (%) | 7 (37) | 68 (24.9) |

| 4–5 (%) | 7 (37) | 139 (50.9) |

| 6–8 (%) | 5 (26.3) | 66 (24.2) |

| 4T by System generated | ||

| 0–3 (%) | 4 (21) | 47 (17.3) |

| 4–5 (%) | 3 (16) | 149 (54.6) |

| 6–8 (%) | 12 (63) | 77 (28.3) |

| Diagnostic Measure | System-Recorded Score | Standardized Physician-Calculated Score |

|---|---|---|

| Sensitivity | 78.9% (54.4–93.9%) | 63.2% (38.4–83.7%) |

| Specificity | 71.8% (66.1–77.0%) | 75.1% (69.5–80.1%) |

| Positive Predictive Value (PPV) | 14.8% (8.5–23.3%) | 17.1% (9.9–26.6%) |

| Negative Predictive Value (NPV) | 98.2% (95.2–99.5%) | 96.0% (92.5–98.1%) |

| 4T Score Category | HIT Positive (n = 19) | HIT Negative (n = 273) | Total Tested (n = 292) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Trained Physicians’ Calculation | |||

| Low (0–3) | 7 (36.8%) | 68 (24.9%) | 75 (25.7%) |

| Intermediate (4–5) | 7 (36.8%) | 139 (50.9%) | 146 (50.0%) |

| High (6–8) | 5 (26.3%) | 66 (24.2%) | 71 (24.3%) |

| System-Recorded Calculation | |||

| Low (0–3) | 4 (21.1%) | 47 (17.2%) | 51 (17.5%) |

| Intermediate (4–5) | 3 (15.8%) | 149 (54.6%) | 152 (52.1%) |

| High (6–8) | 12 (63.2%) | 77 (28.2%) | 89 (30.5%) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Aljumaa, R.M.; Dabaliz, A.; Sabur, H.; Mushtaq, A.; Aljumaa, M.M.; Tamim, H.; Owaidah, T.; Sajid, M.R. Inter-Observer Agreement and Laboratory Correlation of the 4T Scoring Model for Heparin-Induced Thrombocytopenia: A Single-Center Retrospective Study and Literature Review. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 8692. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14248692

Aljumaa RM, Dabaliz A, Sabur H, Mushtaq A, Aljumaa MM, Tamim H, Owaidah T, Sajid MR. Inter-Observer Agreement and Laboratory Correlation of the 4T Scoring Model for Heparin-Induced Thrombocytopenia: A Single-Center Retrospective Study and Literature Review. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(24):8692. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14248692

Chicago/Turabian StyleAljumaa, Roaa M., Alhomam Dabaliz, Homaira Sabur, Ali Mushtaq, Mohammad M. Aljumaa, Hani Tamim, Tarek Owaidah, and Muhammad Raihan Sajid. 2025. "Inter-Observer Agreement and Laboratory Correlation of the 4T Scoring Model for Heparin-Induced Thrombocytopenia: A Single-Center Retrospective Study and Literature Review" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 24: 8692. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14248692

APA StyleAljumaa, R. M., Dabaliz, A., Sabur, H., Mushtaq, A., Aljumaa, M. M., Tamim, H., Owaidah, T., & Sajid, M. R. (2025). Inter-Observer Agreement and Laboratory Correlation of the 4T Scoring Model for Heparin-Induced Thrombocytopenia: A Single-Center Retrospective Study and Literature Review. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(24), 8692. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14248692