Dynamics of Fecal microRNAs Following Fecal Microbiota Transplantation in Alcohol-Related Cirrhosis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Groups and Eligibility Criteria

2.2. Fecal Donor Selection and Preparation Protocol

2.3. Sample Handling and Statistical Methods

2.4. RNA Extraction and miRNA Quantification by RT-qPCR

- Hsa-miR-21-5p;

- Hsa-miR-122-5p;

- Hsa-miR-125-5p;

- Hsa-miR-146-5p;

- Hsa-miR-155-5p.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

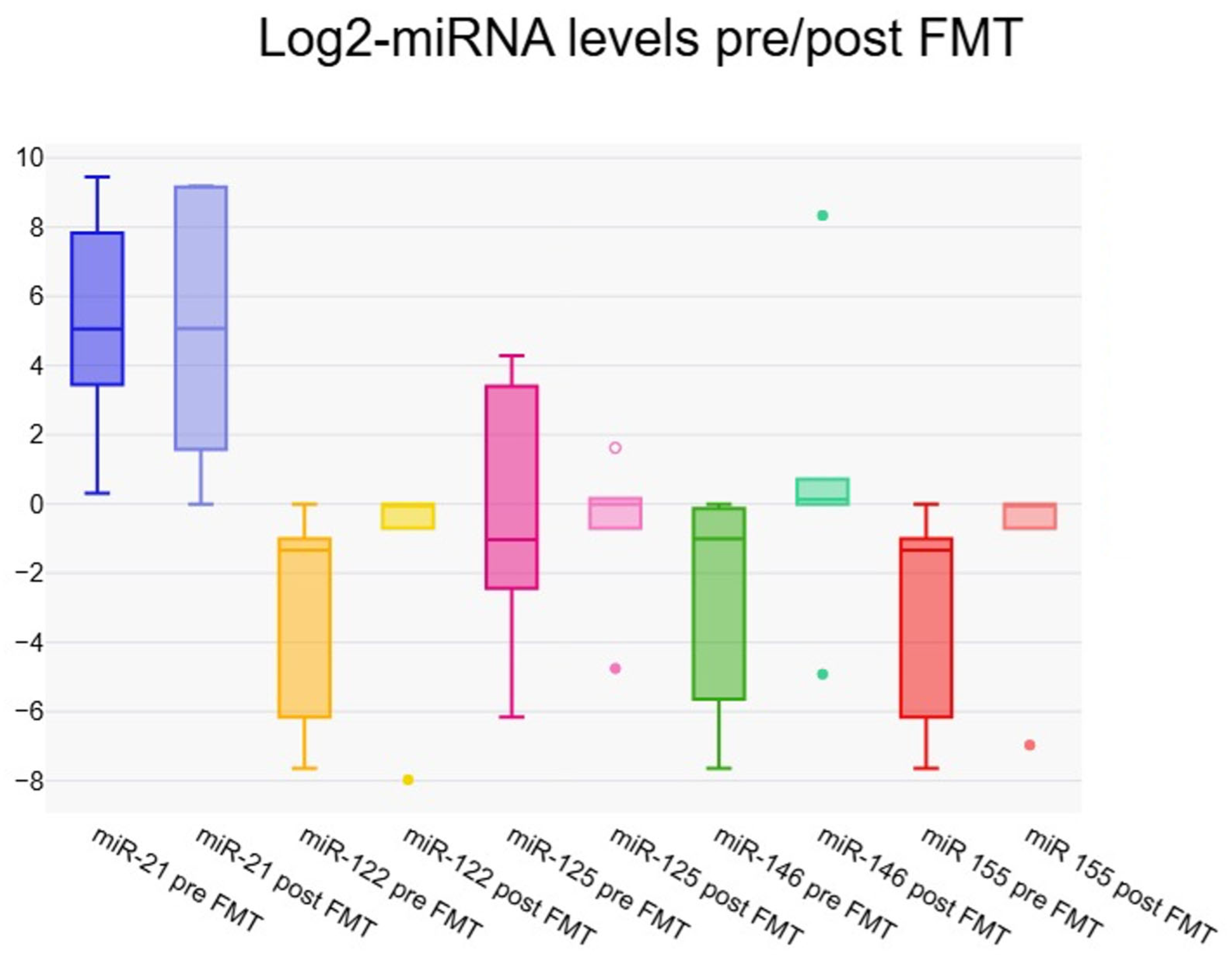

3.1. Fold Change Results

3.2. Correlation Between micro-RNAs and Hepatic Fibrosis Markers Pre-Transplant

3.3. Expression of microRNAs at One Week Post–Fecal Microbiota Transfer

3.4. Dynamic Changes in micro-RNA Expression at One Week Post–Fecal Microbiota Transfer

4. Discussion

5. Limitations and Future Perspectives

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Barnett, R. Liver cirrhosis. Lancet 2018, 392, 275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jagdish, R.K.; Roy, A.; Kumar, K.; Premkumar, M.; Sharma, M.; Rao, P.N.; Reddy, D.N.; Kulkarni, A.V. Pathophysiology and management of liver cirrhosis: From portal hypertension to acute-on-chronic liver failure. Front. Med. 2023, 10, 1060073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devarbhavi, H.; Asrani, S.K.; Arab, J.P.; Nartey, Y.A.; Pose, E.; Kamath, P.S. Global burden of liver disease: 2023 update. J. Hepatol. 2023, 79, 516–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.-N.; Xue, F.; Zhang, N.; Zhang, W.; Hou, J.-J.; Lv, Y.; Xiang, J.-X.; Zhang, X.-F. Global burden of liver cirrhosis and other chronic liver diseases caused by specific etiologies from 1990 to 2019. BMC Public Health 2024, 24, 363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Sun, Z.; Wang, Q.; Wu, K.; Tang, Z.; Zhang, B. Contribution of alcohol use to the global burden of cirrhosis and liver cancer from 1990 to 2019 and projections to 2044. Hepatol. Int. 2023, 17, 1028–1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatima, I.; Jahagirdar, V.; Kulkarni, A.V.; Reddy, R.; Sharma, M.; Menon, B.; Reddy, D.N.; Rao, P.N. Liver Transplantation: Protocol for Recipient Selection, Evaluation, and Assessment. J. Clin. Exp. Hepatol. 2023, 13, 841–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, H.; Zhang, X.; Kuang, M.; Yu, J. The gut–liver axis in immune remodeling of hepatic cirrhosis. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 946628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Chen, Z.; Li, C.; Sun, T.; Luo, X.; Jiang, B.; Liu, M.; Wang, Q.; Li, T.; Cao, J.; et al. Associations between changes in the gut microbiota and liver cirrhosis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Gastroenterol. 2025, 25, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nishikawa, H.; Fukunishi, S.; Asai, A.; Yokohama, K.; Ohama, H.; Nishiguchi, S.; Higuchi, K. Dysbiosis and liver diseases (Review). Int. J. Mol. Med. 2021, 48, 183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Antushevich, H. Fecal microbiota transplantation in disease therapy. Clin. Chim. Acta 2020, 503, 90–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lechner, S.; Yee, M.; Limketkai, B.N.; Pham, E.A. Fecal Microbiota Transplantation for Chronic Liver Diseases: Current Understanding and Future Direction. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2020, 65, 897–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wortelboer, K.; Nieuwdorp, M.; Herrema, H. Fecal microbiota transplantation beyond Clostridioides difficile infections. eBioMedicine 2019, 44, 716–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ardekani, A.M.; Naeini, M.M. The Role of MicroRNAs in Human Diseases. Avicenna J. Med. Biotechnol. 2010, 2, 161–179. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bartel, D.P. MicroRNAs: Genomics, biogenesis, mechanism, and function. Cell 2004, 116, 281–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Liu, T.; Yang, Y.; Cho, W.C.; Flynn, R.J.; Harandi, M.F.; Song, H.; Luo, X.; Zheng, Y. Interplays of liver fibrosis-associated microRNAs: Molecular mechanisms and implications in diagnosis and therapy. Genes Dis. 2023, 10, 1457–1469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, W.; Wang, S.; Wang, Y.; Chen, H.; Nie, H.; Liu, L.; Zou, X.; Gong, Q.; Zheng, B. MicroRNA: Role in macrophage polarization and the pathogenesis of the liver fibrosis. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1147710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashid, H.; Hossain, B.; Siddiqua, T.; Kabir, M.; Noor, Z.; Ahmed, M.; Haque, R. Fecal MicroRNAs as Potential Biomarkers for Screening and Diagnosis of Intestinal Diseases. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2020, 7, 181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bala, S.; Csak, T.; Saha, B.; Zatsiorsky, J.; Kodys, K.; Catalano, D.; Satishchandran, A.; Szabo, G. The pro-inflammatory effects of miR-155 promote liver fibrosis and alcohol-induced steatohepatitis. J. Hepatol. 2016, 64, 1378–1387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Béres, N.J.; Szabó, D.; Kocsis, D.; Szűcs, D.; Kiss, Z.; Müller, K.E.; Lendvai, G.; Kiss, A.; Arató, A.; Sziksz, E.; et al. Role of Altered Expression of miR-146a, miR-155, and miR-122 in Pediatric Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2016, 22, 327–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; He, Y.; Mackowiak, B.; Gao, B. MicroRNAs as regulators, biomarkers and therapeutic targets in liver diseases. Gut 2021, 70, 784–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, T.; Yang, Z.; Kusumanchi, P.; Han, S.; Liangpunsakul, S. Critical Role of microRNA-21 in the Pathogenesis of Liver Diseases. Front. Med. 2020, 7, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valizadeh, S.; Zehtabi, M.; Feiziordaklou, N.; Akbarpour, Z.; Khamaneh, A.M.; Raeisi, M. Upregulation of miR-142 in papillary thyroid carcinoma tissues: A report based on in silico and in vitro analysis. Mol. Biol. Res. Commun. 2022, 11, 133–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Livak, K.J.; Schmittgen, T.D. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods 2001, 25, 402–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szeto, C.-C.; Ng, J.K.-C.; Fung, W.W.-S.; Luk, C.C.-W.; Wang, G.; Chow, K.-M.; Lai, K.-B.; Li, P.K.-T.; Lai, F.M.-M. Kidney microRNA-21 Expression and Kidney Function in IgA Nephropathy. Kidney Med. 2021, 3, 76–82.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larrue, R.; Fellah, S.; Van Der Hauwaert, C.; Hennino, M.-F.; Perrais, M.; Lionet, A.; Glowacki, F.; Pottier, N.; Cauffiez, C. The Versatile Role of miR-21 in Renal Homeostasis and Diseases. Cells 2022, 11, 3525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.-K.; Bär, C.; Thum, T. miR-21, Mediator, and Potential Therapeutic Target in the Cardiorenal Syndrome. Front. Pharmacol. 2020, 11, 726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abbas, N.; Haas, J.A.; Xiao, K.; Fuchs, M.; Just, A.; Pich, A.; Perbellini, F.; Werlein, C.; Ius, F.; Ruhparwar, A.; et al. Inhibition of miR-21: Cardioprotective effects in human failing myocardium ex vivo. Eur. Heart J. 2024, 45, 2016–2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.; Zhang, Z.; Dong, Z.; Liu, X.; Liu, Y.; Li, X.; Xu, Y.; Guo, Y.; Wang, N.; Zhang, M.; et al. MicroRNA-122-5p Aggravates Angiotensin II-Mediated Myocardial Fibrosis and Dysfunction in Hypertensive Rats by Regulating the Elabela/Apelin-APJ and ACE2-GDF15-Porimin Signaling. J. Cardiovasc. Transl. Res. 2022, 15, 535–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colaianni, F.; Zelli, V.; Compagnoni, C.; Miscione, M.S.; Rossi, M.; Vecchiotti, D.; Di Padova, M.; Alesse, E.; Zazzeroni, F.; Tessitore, A. Role of Circulating microRNAs in Liver Disease and HCC: Focus on miR-122. Genes 2024, 15, 1313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caballero-Valderrama, M.D.R.; Bevilacqua, E.; Echevarría, M.; Salvador-Bofill, F.J.; Ordóñez, A.; López-Haldón, J.E.; Smani, T.; Calderón-Sánchez, E.M. Early Myocardial Strain Reduction and miR-122-5p Elevation Associated with Interstitial Fibrosis in Anthracycline-Induced Cardiotoxicity. Biomedicines 2024, 13, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Song, J.W.; Lin, J.Y.; Miao, R.; Zhong, J.C. Roles of MicroRNA-122 in Cardiovascular Fibrosis and Related Diseases. Cardiovasc. Toxicol. 2020, 20, 463–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatlekar, S.; Manne, B.K.; Basak, I.; Edelstein, L.C.; Tugolukova, E.; Stoller, M.L.; Cody, M.J.; Morley, S.C.; Nagalla, S.; Weyrich, A.S.; et al. miR-125a-5p regulates megakaryocyte proplatelet formation via the actin-bundling protein L-plastin. Blood 2020, 136, 1760–1772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatlekar, S.; Tugolukova, E.A.; Bray, P.F. The Mir-99b/Let-7e/Mir-125a cluster Is Associated with Platelet Count and Mean Platelet Volume and Regulates Megakaryocyte Proplatelet Formation. Blood 2019, 134 (Suppl. 1), 1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Rosa, S.; La Bella, S.; Canino, G.; Siller-Matula, J.; Eyleten, C.; Postula, M.; Tamme, L.; Iaconetti, C.; Sabatino, J.; Polimeni, A.; et al. Reciprocal modulation of Linc-223 and its ligand miR-125a on the basis of platelet function level. Eur. Heart J. 2020, 41 (Suppl. 2), ehaa946.3760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Tan, J.; Wang, L.; Pei, G.; Cheng, H.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, S.; He, C.; Fu, C.; Wei, Q. MiR-125 Family in Cardiovascular and Cerebrovascular Diseases. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2021, 9, 799049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.-M.; Kim, T.S.; Jo, E.-K. MiR-146 and miR-125 in the regulation of innate immunity and inflammation. BMB Rep. 2016, 49, 311–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Li, Y. miR-146 promotes HBV replication and expression by targeting ZEB2. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2018, 99, 576–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, Z.; Zheng, R.; Shao, G. Mechanisms and application strategies of miRNA-146a regulating inflammation and fibrosis at molecular and cellular levels (Review). Int. J. Mol. Med. 2022, 51, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rayner, K.J.; Moore, K.J. MicroRNA Control of High-Density Lipoprotein Metabolism and Function. Circ. Res. 2014, 114, 183–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Etzrodt, V.; Idowu, T.O.; Schenk, H.; Seeliger, B.; Prasse, A.; Thamm, K.; Pape, T.; Müller-Deile, J.; Van Meurs, M.; Thum, T.; et al. Role of endothelial microRNA 155 on capillary leakage in systemic inflammation. Crit. Care 2021, 25, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Fold Change |

|---|---|

| miR-21 | 0.384 (0.375–0.832) |

| miR-122 | 1.739 (1.000–2.009) |

| miR-125 | 0.386 (0.164–0.498) |

| miR-146 | 1.704 (1.378–2.009) |

| miR-155 | 1.739 (1.000–2.009) |

| Variable | B-Coefficient | p-Value | 95% CI for B |

|---|---|---|---|

| FIB-4 | |||

| miR-21 | −0.003 | 0.010 * | (−0.006–−0.002) |

| miR-122 | 0.559 | 0.557 | (−2.086–2.159) |

| miR-125 | 0.063 | 0.120 | (0.007–0.124) |

| miR-146 | 0.427 | 0.649 | (−1.204–2.221) |

| miR-155 | 0.559 | 0.541 | (−1.862–2.178) |

| APRI | |||

| miR-21 | −0.001 | 0.019 * | (−0.002–−0.001) |

| miR-122 | 0.172 | 0.470 | (−0.584–0.576) |

| miR-125 | 0.018 | 0.128 | (0.005–0.028) |

| miR-146 | 0.080 | 0.721 | (−0.318–0.518) |

| miR-155 | 0.172 | 0.491 | (−0.558–0.564) |

| E (kPa) | |||

| miR-21 | 0.003 | 0.145 | (−0.006–0.002) |

| miR-122 | −2.318 | 0.212 | (−10.652–0.347) |

| miR-125 | 0.065 | 0.302 | (−0.040–0.205) |

| miR-146 | −1.642 | 0.145 | (−3.670–2.187) |

| miR-155 | −2.315 | 0.210 | (−10.248–0.459) |

| Cap (dB/m) | |||

| miR-21 | −0.009 | 0.778 | (−0.188–0.045) |

| miR-122 | 51.690 | 0.044 * | (3.544–110.521) |

| miR-125 | 3.421 | 0.086 | (1.968–8.614) |

| miR-146 | 60.078 | 0.035 * | (17.412–104.878) |

| miR-155 | 51.690 | 0.052 | (4.201–103.907) |

| Variable | Pre-Transplant | Post-Transplant | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| miR-21 | 32.61 (10.90–34.17) | 12.83 (2.99–87.75) | 0.021 * |

| miR-122 | 0.40 (0.01–0.50) | 1.00 (0.62–1.00) | 0.058 |

| miR-125 | 0.49 (0.18–10.57) | 1.00 (0.62–1.12) | 0.062 |

| miR-146 | 0.69 (0.02–0.92) | 1.00 (1.00–1.21) | 0.002 * |

| miR-155 | 0.40 (0.01–0.50) | 1.00 (0.62–1.00) | 0.068 |

| Variable | B-Coefficient | p-Value | BCa 95% |

|---|---|---|---|

| FIB-4 | |||

| miR-21 | −0.085 | 0.022 * | [−0.149, −0.020] |

| miR-122 | −0.007 | 0.013 * | [−0.012, −0.002] |

| miR-125 | 0.012 | 0.686 | [−0.053, 0.077] |

| miR-146 | −0.004 | 0.001 * | [−0.006, −0.002] |

| miR-155 | −0.007 | 0.013 * | [−0.014, −0.003] |

| APRI | |||

| miR-21 | −0.024 | 0.025 * | [−0.045, −0.04] |

| miR-122 | −0.002 | 0.028 * | [−0.044, −0.001] |

| miR-125 | 0.012 | 0.171 | [−0.006, 0.030] |

| miR-146 | 0.001 | 0.014 * | [−0.002, −0.001] |

| miR-155 | −0.002 | 0.018 * | [−0.004, −0.001] |

| E (kPa) | |||

| miR-21 | −0.239 | 0.016 * | [−0.422, −0.056] |

| miR-122 | −0.019 | 0.027 * | [−0.034, −0.004] |

| miR-125 | 0.047 | 0.578 | [−0.134, 0.229] |

| miR-146 | −0.011 | 0.004 * | [−0.017, −0.004] |

| miR-155 | −0.019 | 0.034 * | [−0.034, −0.004] |

| Cap (dB/m) | |||

| miR-21 | −0.071 | 0.547 | [−0.323, 0.181] |

| miR-122 | −0.006 | 0.560 | [−0.026, 0.015] |

| miR-125 | −0.077 | 0.369 | [−0.260, 0.102] |

| miR-146 | 0.007 | 0.126 | [−0.016, 0.002] |

| miR-155 | −0.007 | 0.595 | [−0.026, 0.017] |

| Variable | miR-21 | miR-122 | miR-125 | miR-146 | miR-155 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CA 19-9 | −0.709 * | 0.462 | 0.333 | −0.085 | 0.316 |

| CEA | −0.587 * | 0.690 * | 0.231 | 0.210 | 0.521 |

| AFP | 0.647 * | −0.276 | −0.387 | −0.427 | −0.230 |

| Monocytes, count | −0.371 | 0.606 * | 0.598 * | 0.337 | 0.458 |

| ESR | −0.042 | 0.498 | 0.273 | −0.024 | 0.681 * |

| T4 free | −0.296 | 0.362 | 0.331 | 0.670 * | 0.206 |

| Variable | miR-21 | miR-122 | miR-125 | miR-146 | miR-155 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Uric acid | 0.609 | 0.029 | 0.609 | 0.377 | 0.029 |

| Amylase | 0.257 | 0.600 * | −0.143 | 0.314 | 0.600 * |

| Total bilirubin | −0.657 * | 0.143 | −0.257 | −0.429 | 0.143 |

| Cholesterol | −0.200 | −0.314 | −0.029 | 0.600 * | −0.314 |

| Creatinine | −0.600 * | −0.257 | −0.543 | −0.600 * | −0.257 |

| Iron-Serum iron | −0.829 * | −0.257 | −0.657 * | 0.200 | −0.257 |

| GGT | −0.029 | −0.829 * | −0.314 | −0.657 * | −0.829 * |

| HDL-Cholesterol | −0.257 | −0.143 | −0.086 | 0.657 * | −0.143 |

| IgG | 0.086 | 0.429 | 0.371 | −0.714 * | 0.429 |

| IgM | −0.029 | 0.086 | −0.200 | −0.714 * | 0.086 |

| LDL-Cholesterol | 0.029 | −0.086 | 0.200 | 0.714 * | −0.086 |

| Magnesium | −0.714 * | −0.486 | −0.771 * | 0.257 | −0.486 |

| CRP | −0.029 | −0.486 | −0.086 | −0.771 * | −0.486 |

| Total proteins | 0.441 | 0.500 | 0.794 * | −0.177 | 0.500 |

| ALT | −0.943 * | −0.029 | −0.543 | 0.029 | −0.029 |

| INR | −0.086 | 0.029 | 0.086 | −0.714 * | 0.029 |

| Leukocytes | −0.657 * | 0.143 | −0.257 | −0.429 | 0.143 |

| Hematocrit | −0.200 | −0.657 * | −0.143 | 0.200 | −0.657 * |

| MCV | 0.657 * | −0.371 | −0.086 | −0.029 | −0.371 |

| Platelets | 0.200 | 0.429 | 0.600 * | −0.429 | 0.429 |

| MPV | −0.086 | −0.200 | −0.600 * | 0.029 | −0.200 |

| PDW | 0.232 | 0.638 * | −0.116 | 0.464 | 0.638 * |

| Macroplatelets | 0.232 | 0.406 | −0.232 | 0.725 * | 0.406 |

| Neutrophils | −0.657 * | 0.143 | −0.257 | −0.429 | 0.143 |

| Lymphocytes | 0.371 | 0.714 * | 0.771 * | 0.486 | 0.714 * |

| NLR | −0.371 | −0.371 | −0.429 | −0.771 * | −0.371 |

| ESR | 0.543 | 0.429 | 0.829 * | −0.429 | 0.429 |

| Folic acid | 0.771 * | 0.200 | 0.143 | 0.029 | 0.200 |

| AFP | −0.800 * | 0.300 | 0.100 | −0.600 | 0.300 |

| Ferritin | 0.314 | −0.371 | −0.086 | −0.714 * | −0.371 |

| Free T4 | −0.771 * | −0.086 | −0.371 | 0.029 | −0.086 |

| TSH | −0.600 * | −0.029 | −0.200 | −0.486 | −0.029 |

| Vitamin B12 | −0.029 | 0.086 | −0.200 | −0.714 * | 0.086 |

| BMI | −0.714 * | 0.086 | −0.086 | 0.086 | 0.086 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ichim, C.; Boicean, A.; Todor, S.B.; Boeras, I.; Anderco, P.; Birlutiu, V. Dynamics of Fecal microRNAs Following Fecal Microbiota Transplantation in Alcohol-Related Cirrhosis. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 8623. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14248623

Ichim C, Boicean A, Todor SB, Boeras I, Anderco P, Birlutiu V. Dynamics of Fecal microRNAs Following Fecal Microbiota Transplantation in Alcohol-Related Cirrhosis. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(24):8623. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14248623

Chicago/Turabian StyleIchim, Cristian, Adrian Boicean, Samuel Bogdan Todor, Ioana Boeras, Paula Anderco, and Victoria Birlutiu. 2025. "Dynamics of Fecal microRNAs Following Fecal Microbiota Transplantation in Alcohol-Related Cirrhosis" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 24: 8623. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14248623

APA StyleIchim, C., Boicean, A., Todor, S. B., Boeras, I., Anderco, P., & Birlutiu, V. (2025). Dynamics of Fecal microRNAs Following Fecal Microbiota Transplantation in Alcohol-Related Cirrhosis. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(24), 8623. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14248623