Feasibility and Preliminary Effects of Ballet-Based Group Dance Intervention in Relapsing–Remitting Multiple Sclerosis: A Pilot Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Intervention

2.2. Outcome Measures

2.3. Adherence and Adverse Events

2.4. Participants Satisfaction

2.5. Statistical Analysis

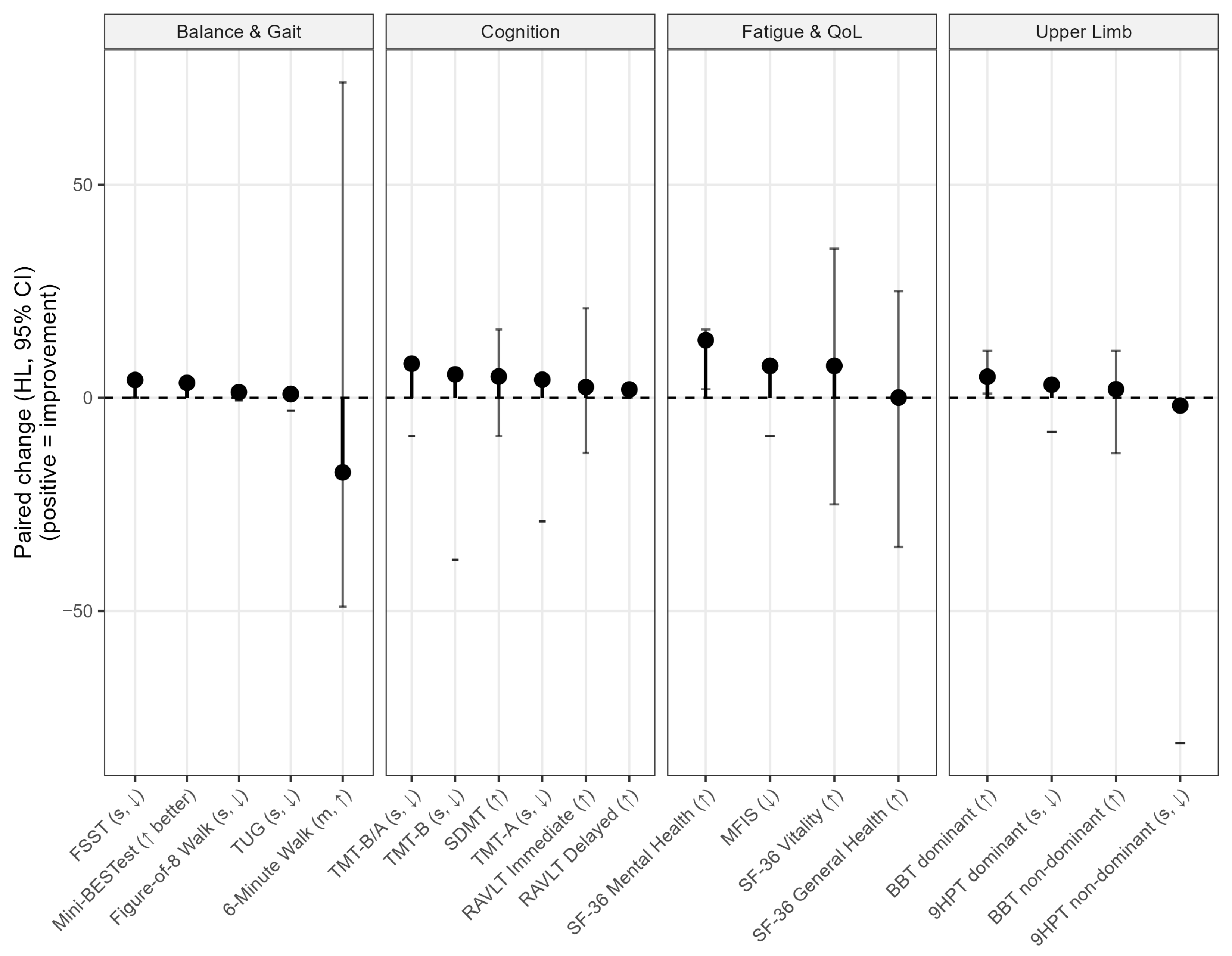

3. Results

Semi-Structured Interview

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Individual Demographic and Clinical Characteristics

| Age | Gender | Education | Disease Duration | EDSS | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Subject 1 | 31 | F | 8 | 7 | 3.5 |

| Subject 2 | 44 | M | 13 | 10 | 4.5 |

| Subject 3 | 37 | F | 13 | 8 | 3.5 |

| Subject 4 | 44 | M | 18 | 10 | 4.5 |

| Drop out 1 | 35 | F | 13 | 10 | 1.5 |

| Drop out 2 | 45 | F | 8 | 1 | 4 |

References

- Walton, C.; King, R.; Rechtman, L.; Kaye, W.; Leray, E.; Marrie, R.A.; Robertson, N.; La Rocca, N.; Uitdehaag, B.; Van Der Mei, I.; et al. Rising prevalence of multiple sclerosis worldwide: Insights from the Atlas of MS, third edition. Mult. Scler. J. 2020, 26, 1816–1821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halabchi, F.; Alizadeh, Z.; Sahraian, M.A.; Abolhasani, M. Exercise prescription for patients with multiple sclerosis; potential benefits and practical recommendations. BMC Neurol. 2017, 17, 185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jawad, A.; Baattaiah, B.A.; Alharbi, M.D.; Chevidikunnan, M.F.; Khan, F. Factors contributing to falls in people with multiple sclerosis: The exploration of the moderation and mediation effects. Mult. Scler. Relat. Disord. 2023, 76, 104838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benedict, R.H.B.; Amato, M.P.; DeLuca, J.; Geurts, J.J.G. Cognitive impairment in multiple sclerosis: Clinical management, MRI, and therapeutic avenues. Lancet Neurol. 2020, 19, 860–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doskas, T.; Vavougios, G.D.; Karampetsou, P.; Kormas, C.; Synadinakis, E.; Stavrogianni, K.; Sionidou, P.; Serdari, A.; Vorvolakos, T.; Iliopoulos, I.; et al. Neurocognitive impairment and social cognition in multiple sclerosis. Int. J. Neurosci. 2022, 132, 1229–1244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okuda, D.T.; Siva, A.; Kantarci, O.; Inglese, M.; Katz, I.; Tutuncu, M.; Keegan, B.M.; Donlon, S.; Hua, L.H.; Vidal-Jordana, A.; et al. Radiologically Isolated Syndrome: 5-Year Risk for an Initial Clinical Event. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e90509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, J.; Harrison, J.; Palmer, K. Risk factors for relapse in relapsing remitting multiple sclerosis. Br. J. Neurosci. Nurs. 2021, 17, S34–S36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, L.; Xi, H.; Zhang, S.; Zhou, Y.; Tao, X.; Lv, Y.; Hou, X.; Yu, L. Effects of exercise in people with multiple sclerosis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Public Health 2024, 12, 1387658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalb, R.; Brown, T.R.; Coote, S.; Costello, K.; Dalgas, U.; Garmon, E.; Giesser, B.; Halper, J.; Karpatkin, H.; Keller, J.; et al. Exercise and lifestyle physical activity recommendations for people with multiple sclerosis throughout the disease course. Mult. Scler. J. 2020, 26, 1459–1469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Earhart, G.M. Dance as therapy for individuals with Parkinson disease. Eur. J. Phys. Rehabil. Med. 2009, 45, 231–238. [Google Scholar]

- Britten, L. Christine Dancing in time: Feasibility and acceptability of a contemporary dance programme to modify risk factors for falling in community dwelling older adults. BMC Geriatr. 2017, 17, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hwang, P.W.-N.; Braun, K.L. The Effectiveness of Dance Interventions to Improve Older Adults’ Health: A Systematic Literature Review. Altern. Ther. Health Med. 2015, 21, 64–70. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Granacher, U.; Muehlbauer, T.; Bridenbaugh, S.A.; Wolf, M.; Roth, R.; Gschwind, Y.; Wolf, I.; Mata, R.; Kressig, R.W. Effects of a Salsa Dance Training on Balance and Strength Performance in Older Adults. Gerontology 2012, 58, 305–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hui, E.; Chui, B.T.; Woo, J. Effects of dance on physical and psychological well-being in older persons. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2009, 49, e45–e50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shigematsu, R. Dance-based aerobic exercise may improve indices of falling risk in older women. Age Ageing 2002, 31, 261–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cepeda, C.C.P.; Lodovico, A.; Fowler, N.; Rodacki, A.L.F. Effect of an Eight-Week Ballroom Dancing Program on Muscle Architecture in Older Adult Females. J. Aging Phys. Act. 2015, 23, 607–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coubard, O.A.; Ferrufino, L.; Nonaka, T.; Zelada, O.; Bril, B.; Dietrich, G. One month of contemporary dance modulates fractal posture in aging. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2014, 6, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrufino, L.; Bril, B.; Dietrich, G.; Nonaka, T.; Coubard, O.A. Practice of Contemporary Dance Promotes Stochastic Postural Control in Aging. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2011, 5, 169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallmann, H.W.; Gillis, C.B.; Alpert, P.T.; Miller, S.K. The Effect of a Senior Jazz Dance Class on Static Balance in Healthy Women Over 50 Years of Age: A Pilot Study. Biol. Res. Nurs. 2009, 10, 257–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Earhart, G.M. Dynamic control of posture across locomotor tasks. Mov. Disord. 2013, 28, 1501–1508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hackney, M.E.; Kantorovich, S.; Levin, R.; Earhart, G.M. Effects of Tango on Functional Mobility in Parkinson’s Disease: A Preliminary Study. J. Neurol. Phys. Ther. 2007, 31, 173–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hackney, M.E.; Earhart, G.M. Effects of Dance on Gait and Balance in Parkinson’s Disease: A Comparison of Partnered and Nonpartnered Dance Movement. Neurorehabil. Neural Repair 2010, 24, 384–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sofianidis, G.; Dimitriou, A.-M.; Hatzitaki, V. A Comparative Study of the Effects of Pilates and Latin Dance on Static and Dynamic Balance in Older Adults. J. Aging Phys. Act. 2017, 25, 412–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eyigor, S.; Karapolat, H.; Durmaz, B.; Ibisoglu, U.; Cakir, S. A randomized controlled trial of Turkish folklore dance on the physical performance, balance, depression and quality of life in older women. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2009, 48, 84–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pacheco, E.; Hoyos, D.P.; Watts, W.J.; Lema, L.; Arango, C.M. Feasibility Study: Colombian Caribbean Folk Dances to Increase Physical Fitness and Health-Related Quality of Life in Older Women. J. Aging Phys. Act. 2016, 24, 284–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sofianidis, G.; Hatzitaki, V.; Douka, S.; Grouios, G. Effect of a 10-Week Traditional Dance Program on Static and Dynamic Balance Control in Elderly Adults. J. Aging Phys. Act. 2009, 17, 167–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldana-Benítez, D.; Caicedo-Pareja, M.J.; Sánchez, D.P.; Ordoñez-Mora, L.T. Dance as a neurorehabilitation strategy: A systematic review. J. Bodyw. Mov. Ther. 2023, 35, 348–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, S.; Martinez, M.J.; Parsons, L.M. The Neural Basis of Human Dance. Cereb. Cortex 2006, 16, 1157–1167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henschke, J.U.; Pakan, J.M.P. Engaging distributed cortical and cerebellar networks through motor execution, observation, and imagery. Front. Syst. Neurosci. 2023, 17, 1165307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koshimori, Y.; Thaut, M.H. Future perspectives on neural mechanisms underlying rhythm and music based neurorehabilitation in Parkinson’s disease. Ageing Res. Rev. 2018, 47, 133–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meulenberg, C.J.W.; Rehfeld, K.; Jovanović, S.; Marusic, U. Unleashing the potential of dance: A neuroplasticity-based approach bridging from older adults to Parkinson’s disease patients. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2023, 15, 1188855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, G.; He, H.; Huang, M.; Zhang, X.; Lu, J.; Lai, Y.; Luo, C.; Yao, D. Identifying enhanced cortico-basal ganglia loops associated with prolonged dance training. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 10271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bégel, V.; Bachrach, A.; Dalla Bella, S.; Laroche, J.; Clément, S.; Riquet, A.; Dellacherie, D. Dance Improves Motor, Cognitive, and Social Skills in Children with Developmental Cerebellar Anomalies. Cerebellum 2022, 21, 264–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Emmanouilidis, S.; Hackney, M.E.; Slade, S.C.; Heng, H.; Jazayeri, D.; Morris, M.E. Dance Is an Accessible Physical Activity for People with Parkinson’s Disease. Park. Dis. 2021, 2021, 7516504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, E.; Webster, A.; Whiteside, B.; Paul, L. Dance for Multiple Sclerosis: A Systematic Review. Int. J. MS Care 2023, 25, 176–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lihala, S.; Mitra, S.; Neogy, S.; Datta, N.; Choudhury, S.; Chatterjee, K.; Mondal, B.; Halder, S.; Roy, A.; Sengupta, M.; et al. Dance movement therapy in rehabilitation of Parkinson’s disease—A feasibility study. J. Bodyw. Mov. Ther. 2021, 26, 12–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenzweig, M.R.; Bennett, E.L. Psychobiology of plasticity: Effects of training and experience on brain and behavior. Behav. Brain Res. 1996, 78, 57–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baroncelli, L.; Braschi, C.; Spolidoro, M.; Begenisic, T.; Sale, A.; Maffei, L. Nurturing brain plasticity: Impact of environmental enrichment. Cell Death Differ. 2010, 17, 1092–1103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barros, W.; David, M.; Souza, A.; Silva, M.; Matos, R. Can the effects of environmental enrichment modulate BDNF expression in hippocampal plasticity? A systematic review of animal studies. Synapse 2019, 73, e22103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, A.J.; Banwell, B.L.; Barkhof, F.; Carroll, W.M.; Coetzee, T.; Comi, G.; Correale, J.; Fazekas, F.; Filippi, M.; Freedman, M.S.; et al. Diagnosis of multiple sclerosis: 2017 revisions of the McDonald criteria. Lancet Neurol. 2018, 17, 162–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsen, D.L.; Attkisson, C.C.; Hargreaves, W.A.; Nguyen, T.D. Assessment of client/patient satisfaction: Development of a general scale. Eval. Program Plann. 1979, 2, 197–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patterson, K.K.; Wong, J.S.; Prout, E.C.; Brooks, D. Dance for the rehabilitation of balance and gait in adults with neurological conditions other than Parkinson’s disease: A systematic review. Heliyon 2018, 4, e00584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bronner, S. Differences in segmental coordination and postural control in a multi-joint dance movement: Développé arabesque. J. Dance Med. Sci. Off. Publ. Int. Assoc. Dance Med. Sci. 2012, 16, 26–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prosperini, L.; Fortuna, D.; Giannì, C.; Leonardi, L.; Marchetti, M.R.; Pozzilli, C. Home-Based Balance Training Using the Wii Balance Board: A Randomized, Crossover Pilot Study in Multiple Sclerosis. Neurorehabil. Neural Repair 2013, 27, 516–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wallin, A.; Johansson, S.; Brincks, J.; Dalgas, U.; Franzén, E.; Callesen, J. Effects of Balance Exercise Interventions on Balance-Related Performance in People with Multiple Sclerosis: A Systematic Review and a Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Neurorehabil. Neural Repair 2024, 38, 775–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, E.C.; Haussler, A.M.; Tueth, L.E.; Baudendistel, S.T.; Earhart, G.M. Graceful gait: Virtual ballet classes improve mobility and reduce falls more than wellness classes for older women. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2024, 16, 1289368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angevaren, M.; Aufdemkampe, G.; Verhaar, H.; Aleman, A.; Vanhees, L. Physical activity and enhanced fitness to improve cognitive function in older people without known cognitive impairment. In Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews; The Cochrane Collaboration, Ed.; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.: Chichester, UK, 2008; p. CD005381. [Google Scholar]

- Rademacher, A.; Joisten, N.; Proschinger, S.; Bloch, W.; Gonzenbach, R.; Kool, J.; Langdon, D.; Bansi, J.; Zimmer, P. Cognitive Impairment Impacts Exercise Effects on Cognition in Multiple Sclerosis. Front. Neurol. 2021, 11, 619500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandroff, B.M.; Wylie, G.R.; Baird, J.F.; Jones, C.D.; Diggs, M.D.; Genova, H.; Bamman, M.M.; Cutter, G.R.; DeLuca, J.; Motl, R.W. Effects of walking exercise training on learning and memory and hippocampal neuroimaging outcomes in MS: A targeted, pilot randomized controlled trial. Contemp. Clin. Trials 2021, 110, 106563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leavitt, V.M.; Cirnigliaro, C.; Cohen, A.; Farag, A.; Brooks, M.; Wecht, J.M.; Wylie, G.R.; Chiaravalloti, N.D.; DeLuca, J.; Sumowski, J.F. Aerobic exercise increases hippocampal volume and improves memory in multiple sclerosis: Preliminary findings. Neurocase 2014, 20, 695–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Springer, S.; Giladi, N.; Peretz, C.; Yogev, G.; Simon, E.S.; Hausdorff, J.M. Dual-tasking effects on gait variability: The role of aging, falls, and executive function. Mov. Disord. 2006, 21, 950–957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fong Yan, A.; Nicholson, L.L.; Ward, R.E.; Hiller, C.E.; Dovey, K.; Parker, H.M.; Low, L.-F.; Moyle, G.; Chan, C. The Effectiveness of Dance Interventions on Psychological and Cognitive Health Outcomes Compared with Other Forms of Physical Activity: A Systematic Review with Meta-analysis. Sports Med. 2024, 54, 1179–1205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, A.; Bunyan, S.; Suh, J.; Huenink, P.; Gregory, T.; Gambon, S.; Miller, D. Ballroom dance for persons with multiple sclerosis: A pilot feasibility study. Disabil. Rehabil. 2020, 42, 1115–1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devlin, K.; Alshaikh, J.T.; Pantelyat, A. Music Therapy and Music-Based Interventions for Movement Disorders. Curr. Neurol. Neurosci. Rep. 2019, 19, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Stages | Description | Time |

|---|---|---|

| Warm-up | Mobility exercises while standing | 10′ |

| Ballet stage and choreography | Balance exercises while standing | 30′ |

| Upper limb exercises while sitting | 10′ | |

| Final stage | Stretching while sitting | 5′ |

| Stretching while standing | 5′ |

| Mean (M) | Standard Deviation (SD) | Minimum | Maximum | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 39.25 | 6.55 | 31 | 45 |

| Gender (male) | 2 (2) | |||

| Education | 13 | 4.08 | 8 | 13 |

| Disease duration | 8.75 | 1.5 | 1 | 10 |

| EDSS | 4 | 0.5 | 1.5 | 4.5 |

| Not at All | Slightly | Moderately | Excellent | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| How would you rate the quality of service you received? | 0% | 0% | 50% | 50% |

| Did you get the kind of service you wanted? | 0% | 0% | 100% | 0% |

| To what extent has our service met your needs? | 0% | 0% | 100% | 0% |

| If a friend were in need of similar help, would you recommend our service to him or her? | 0% | 0% | 50% | 50% |

| How satisfied are you with the amount of help you received? | 0% | 0% | 50% | 50% |

| Have the services you received helped you to deal more effectively with your problems? | 0% | 25% | 75% | 0% |

| In an overall, general sense, how satisfied are you with the service you received? | 0% | 0% | 50% | 50% |

| If you were to seek help again, would you come back to our service? | 0% | 0% | 75% | 25% |

| T0 Median (Q1–Q3 Quartile) | T1 Median (Q1–Q3 Quartile) | |

|---|---|---|

| MINI BES-TEST, score | 20.00 (16.75–23.25) | 23.50 (20.50–26.50) |

| FFST, seconds | 20.56 (13.08–30.51) | 11.39 (6.67–14.75) |

| 6MWT, meters | 273.50 (232.5–313.5) | 293.50 (136.75–348.80) |

| F8WT, seconds | 10.10 (8.20–13.18) | 10.00 (3.25–11.50) |

| BBT (dominant hand), score | 29.00 (25.50–33.00) | 31.00 (5.00–34.75) |

| BBT (non-dominant hand), score | 30.50 (27.00–34.25) | 30.00 (9.25–35.50) |

| 9HPT (dominant hand), seconds | 16.94 (14.27–24.22) | 18.00 (6.43–21.43) |

| 9HPT (non-dominant hand), seconds | 25.15 (21.43–33.48) | 35.46 (40.75–62.29) |

| T0 Median (Q1–Q3 Quartile) | T1 Median (Q1–Q3 Quartile) | |

|---|---|---|

| RAVLT Immediate Recall, score | 46.46 (44.46–47.46) | 49.17 (37.23–59.95) |

| RAVLT Delayed Recall, score | 9.01 (8.68–9.54) | 10.84 (9.54–11.51) |

| SDMT, score | 32.72 (30.33–39.99) | 48.22 (39.33–51.49) |

| TMT-A, time | 33.07 (26.56–39.61) | 26.07 (21.81–40.11) |

| TMT-B, time | 99.70 (72.49–124.90) | 75.16 (60.24–107.1) |

| MFIS, score | 47.00 (39.75–54.75) | 40.50 (39.25–41.25) |

| SF-36 (General Health), score | 35.00 (20.00–48.75) | 35.00 (28.75–41.25) |

| SF-36 (Mental Health), score | 40.00 (35.00–49.00) | 52.00 (50.00–54.00) |

| SF-36 (Vitality), score | 25.00 (23.75–35.00) | 40.00 (37.50–43.75) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ivaldi, D.; Lombardo, R.; Triolo, G.; Restuccia, G.; Susinna, C.; Bonanno, L.; Rifici, C.; D'Aleo, G.; Sessa, E.; Quartarone, A.; et al. Feasibility and Preliminary Effects of Ballet-Based Group Dance Intervention in Relapsing–Remitting Multiple Sclerosis: A Pilot Study. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 8612. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238612

Ivaldi D, Lombardo R, Triolo G, Restuccia G, Susinna C, Bonanno L, Rifici C, D'Aleo G, Sessa E, Quartarone A, et al. Feasibility and Preliminary Effects of Ballet-Based Group Dance Intervention in Relapsing–Remitting Multiple Sclerosis: A Pilot Study. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(23):8612. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238612

Chicago/Turabian StyleIvaldi, Daniela, Roberta Lombardo, Gabriele Triolo, Giovanni Restuccia, Carla Susinna, Lilla Bonanno, Carmela Rifici, Giangaetano D'Aleo, Edoardo Sessa, Angelo Quartarone, and et al. 2025. "Feasibility and Preliminary Effects of Ballet-Based Group Dance Intervention in Relapsing–Remitting Multiple Sclerosis: A Pilot Study" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 23: 8612. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238612

APA StyleIvaldi, D., Lombardo, R., Triolo, G., Restuccia, G., Susinna, C., Bonanno, L., Rifici, C., D'Aleo, G., Sessa, E., Quartarone, A., & Lo Buono, V. (2025). Feasibility and Preliminary Effects of Ballet-Based Group Dance Intervention in Relapsing–Remitting Multiple Sclerosis: A Pilot Study. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(23), 8612. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238612