Outcome of Fontan Patients After Reaching Adolescence: The Impact of Hypoplastic Left Heart Syndrome

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Laboratory Values

2.2. Echocardiography

2.3. Endpoints

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

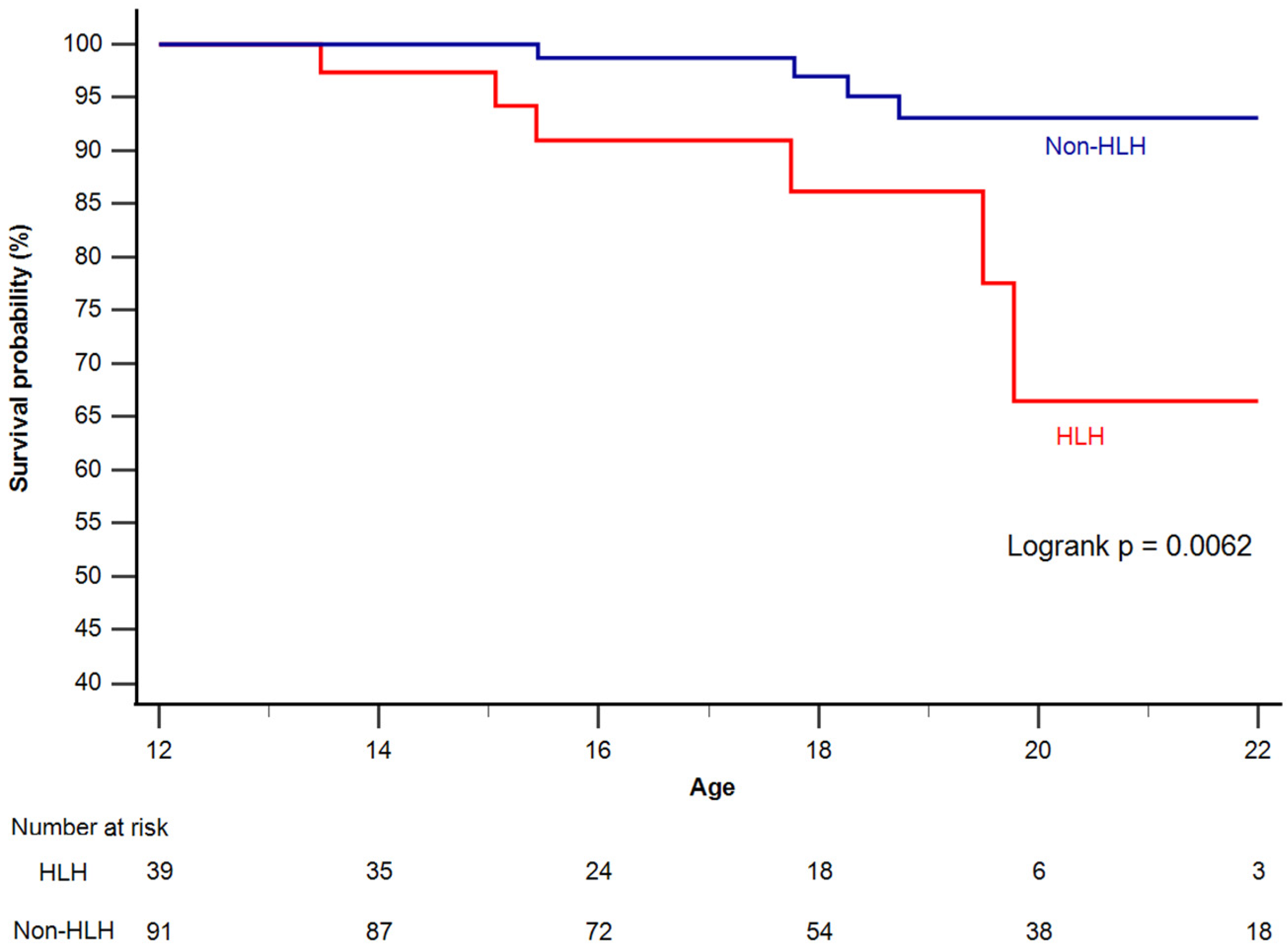

3.1. Survival

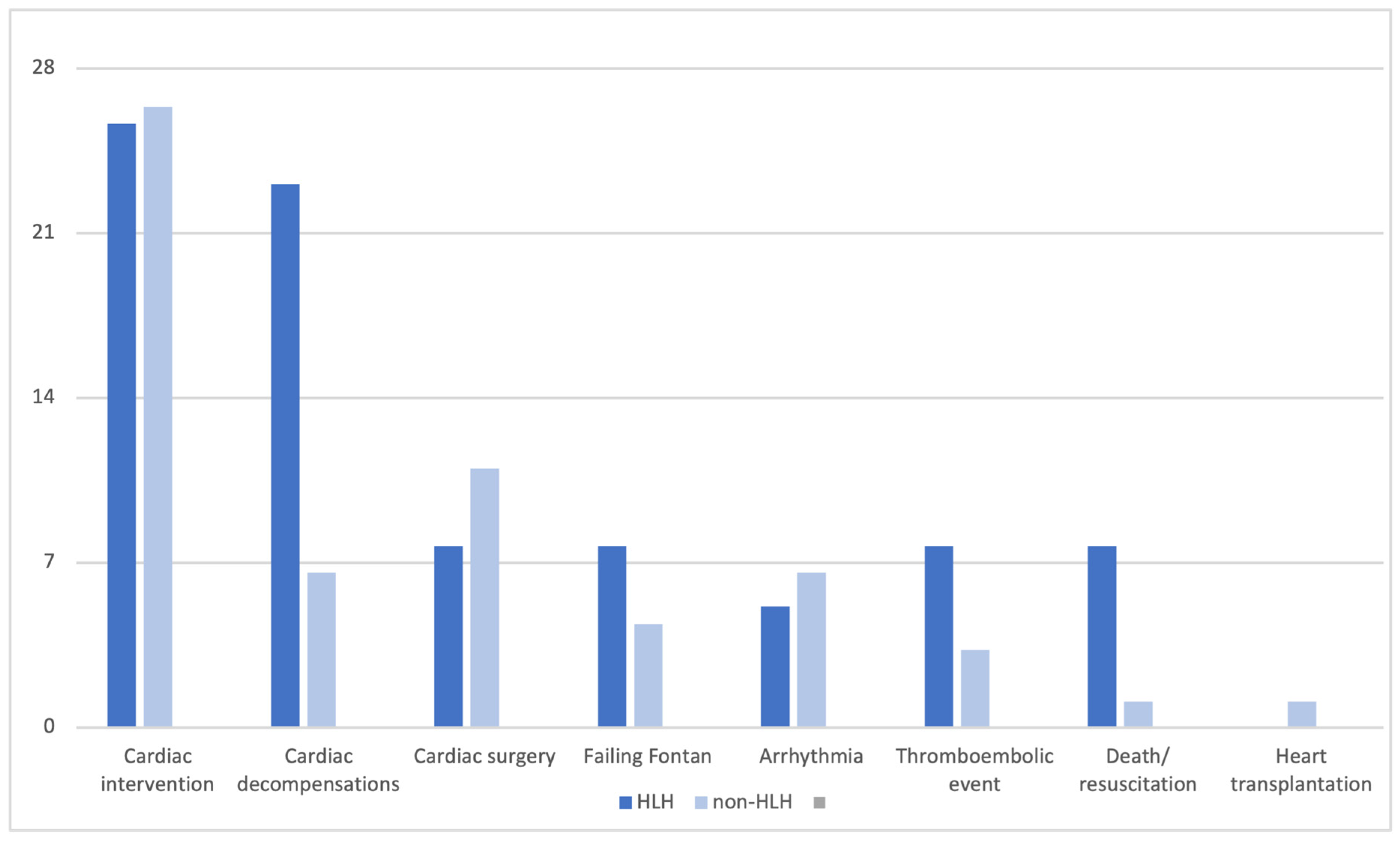

3.2. Primary and Secondary Endpoints

3.3. Clinical Outcome

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Fontan, F.; Baudet, E. Surgical repair of tricuspid atresia. Thorax 1971, 26, 240–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ono, M.; Kasnar-Samprec, J.; Hager, A.; Cleuziou, J.; Burri, M.; Langenbach, C.; Callegari, A.; Strbad, M.; Vogt, M.; Horer, J.; et al. Clinical outcome following total cavopulmonary connection: A 20-year single-centre experience. Eur. J. Cardiothorac. Surg. 2016, 50, 632–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padalino, M.A.; Constantine, A.; Bergonzoni, E.; Cao, I.; Horer, J.; Ono, M.; Staehler, H.; Sames-Dolzer, E.; Gierlinger, G.; Hazekamp, M.; et al. Early outcomes of children with univentricular circulation undergoing Fontan surgery: The EuroFontan registry. Eur. Heart J. 2025, ehaf835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talla, M.; Best, N.; Challa, A.; Balakumar, S.; Lopez-Tejero, S.; Huszti, E.; Horlick, E.; Alonso-Gonzalez, R.; Abrahamyan, L. Long-Term Outcomes of Fontan Patients with an Extracardiac Conduit: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Can. J. Cardiol. 2025, 41, 1162–1171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammer, V.; Schaeffer, T.; Staehler, H.; Heinisch, P.P.; Burri, M.; Piber, N.; Lemmer, J.; Hager, A.; Ewert, P.; Horer, J.; et al. Protein-Losing Enteropathy and Plastic Bronchitis Following the Total Cavopulmonary Connections. World J. Pediatr. Congenit. Heart Surg. 2023, 14, 691–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, T.M.; Aiyagari, R.; Hirsch, J.C.; Ohye, R.G.; Bove, E.L.; Devaney, E.J. Risk factor analysis for second-stage palliation of single ventricle anatomy. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 2012, 93, 614–618, discussion 619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kogon, B.E.; Plattner, C.; Leong, T.; Simsic, J.; Kirshbom, P.M.; Kanter, K.R. The bidirectional Glenn operation: A risk factor analysis for morbidity and mortality. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2008, 136, 1237–1242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biko, D.M.; DeWitt, A.G.; Pinto, E.M.; Morrison, R.E.; Johnstone, J.A.; Griffis, H.; O’Byrne, M.L.; Fogel, M.A.; Harris, M.A.; Partington, S.L.; et al. MRI Evaluation of Lymphatic Abnormalities in the Neck and Thorax after Fontan Surgery: Relationship with Outcome. Radiology 2019, 291, 774–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keizman, E.; Abarbanel, I.; Salem, Y.; Mishaly, D.; Serraf, A.E.; Pollak, U. The Impact of Dominant Ventricular Morphology on the Early Postoperative Course After the Glenn Procedure. Pediatr. Cardiol. 2023, 44, 1076–1082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pollak, U.; Abarbanel, I.; Salem, Y.; Serraf, A.E.; Mishaly, D. Dominant Ventricular Morphology and Early Postoperative Course After the Fontan Procedure. World J. Pediatr. Congenit. Heart Surg. 2022, 13, 346–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponzoni, M.; Azzolina, D.; Vedovelli, L.; Gregori, D.; Di Salvo, G.; D’Udekem, Y.; Vida, V.; Padalino, M.A. Ventricular morphology of single-ventricle hearts has a significant impact on outcomes after Fontan palliation: A meta-analysis. Eur. J. Cardiothorac. Surg. 2022, 62, ezac535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atz, A.M.; Zak, V.; Mahony, L.; Uzark, K.; D’Agincourt, N.; Goldberg, D.J.; Williams, R.V.; Breitbart, R.E.; Colan, S.D.; Burns, K.M.; et al. Longitudinal Outcomes of Patients with Single Ventricle After the Fontan Procedure. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2017, 69, 2735–2744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdul-Khaliq, H.; Gomes, D.; Meyer, S.; von Kries, R.; Wagenpfeil, S.; Pfeifer, J.; Poryo, M. Trends of mortality rate in patients with congenital heart defects in Germany-analysis of nationwide data of the Federal Statistical Office of Germany. Clin. Res. Cardiol. 2024, 113, 750–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aljiffry, A.; Harriott, A.; Patel, S.; Scheel, A.; Amedi, A.; Evans, S.; Xiang, Y.; Harding, A.; Shashidharan, S.; Beshish, A.G. Outcomes, mortality risk factors, and functional status post-Norwood: A single-center study. Int. J. Cardiol. Congenit. Heart Dis. 2024, 17, 100533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghimire, L.V.; Chou, F.S.; Pundi, K.; Moon-Grady, A.J. In-Hospital Outcomes in Fontan Completion Surgery According to Age. Am. J. Cardiol. 2022, 166, 81–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zoghbi, W.A.; Enriquez-Sarano, M.; Foster, E.; Grayburn, P.A.; Kraft, C.D.; Levine, R.A.; Nihoyannopoulos, P.; Otto, C.M.; Quinones, M.A.; Rakowski, H.; et al. Recommendations for evaluation of the severity of native valvular regurgitation with two-dimensional and Doppler echocardiography. J. Am. Soc. Echocardiogr. 2003, 16, 777–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- d’Udekem, Y.; Iyengar, A.J.; Galati, J.C.; Forsdick, V.; Weintraub, R.G.; Wheaton, G.R.; Bullock, A.; Justo, R.N.; Grigg, L.E.; Sholler, G.F.; et al. Redefining expectations of long-term survival after the Fontan procedure: Twenty-five years of follow-up from the entire population of Australia and New Zealand. Circulation 2014, 130, S32–S38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pundi, K.N.; Johnson, J.N.; Dearani, J.A.; Pundi, K.N.; Li, Z.; Hinck, C.A.; Dahl, S.H.; Cannon, B.C.; O’Leary, P.W.; Driscoll, D.J.; et al. 40-Year Follow-Up After the Fontan Operation: Long-Term Outcomes of 1,052 Patients. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2015, 66, 1700–1710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gordon-Walker, T.T.; Bove, K.; Veldtman, G. Fontan-associated liver disease: A review. J. Cardiol. 2019, 74, 223–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, W.M.; Valente, A.M.; Hickey, E.J.; Clift, P.; Burchill, L.; Emmanuel, Y.; Gibson, P.; Greutmann, M.; Grewal, J.; Grigg, L.E.; et al. Outcomes of Patients with Hypoplastic Left Heart Syndrome Reaching Adulthood After Fontan Palliation: Multicenter Study. Circulation 2018, 137, 978–981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalén, M.; Odermarsky, M.; Liuba, P.; Ramgren, J.J.; Synnergren, M.; Sunnegårdh, J. Long-Term Survival After Single-Ventricle Palliation: A Swedish Nationwide Cohort Study. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2024, 13, e031722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dib, N.; Chaix, M.A.; Samuel, M.; Honfo, S.H.; Hamilton, R.M.; Aboulhosn, J.; Broberg, C.S.; Cohen, S.; Cook, S.; Dore, A.; et al. Cardiovascular Outcomes in Fontan Patients with Right vs Left Univentricular Morphology: A Multicenter Study. JACC Adv. 2024, 3, 100871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miranda, W.R.; Borlaug, B.A.; Jain, C.C.; Anderson, J.H.; Hagler, D.J.; Connolly, H.M.; Egbe, A.C. Exercise-induced changes in pulmonary artery wedge pressure in adults post-Fontan versus heart failure with preserved ejection fraction and non-cardiac dyspnoea. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 2023, 25, 17–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hager, A. Invasive Cardiopulmonary Exercise Testing in Patients with Fontan Circulation. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2023, 81, 1601–1604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Total n = 130 | Dominant LV n = 72 | Dominant RV (non-HLHS) n = 19 | HLHS n = 39 | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FU time (years) | 16.2 ± 2.9 | 16.5 ± 3.0 | 16.8 ± 2.7 | 15.5 ± 2.7 | 0.195 |

| Age at FU (years) | 18.6 ± 3.2 | 19.0 ± 3.5 | 19.7 ± 2.9 | 17.5 ± 2.5 | 0.025 |

| Age at TCPC | 2.4 ± 1.3 | 2.5 ± 1.3 | 2.9 ± 1.6 | 2.0 ± 0.6 | 0.3 |

| Male | 88 | 44 | 12 | 32 | 0.071 |

| Underlying cardiac anomaly | |||||

| HLHS | 39 | 39 | |||

| TA | 28 | 28 | |||

| DILV | 18 | 18 | |||

| DORV | 16 | 7 | 9 | ||

| CAVSD | 4 | 2 | 2 | ||

| Other | 25 | 17 | 8 | ||

| Other morphological characteristics | |||||

| VSD | 73 | 51 | 12 | 10 | |

| TAPVC | 3 | 1 | 2 | 0 | |

| PAPVC | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0 | |

| Hypoplastic aortic arch | 20 | 10 | 4 | 6 | |

| Heterotaxy | 8 | 4 | 4 | 0 | |

| Azygos continuity | 7 | 5 | 2 | 0 |

| Total n = 130 | Dominant LV n = 72 | Dominant RV n = 19 | HLHS n = 39 | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hospital admission after TCPC | 82 (63%) | 46 (64%) | 13 (68%) | 23 (59%) | 0.275 |

| MACE | 11 (9%) | 3 (4%) | 2 (11%) | 6 (15%) | 0.039 |

| Failing Fontan | 10 (8%) | 5 (7%) | 1 (5%) | 4 (10%) | 0.489 |

| Extended MACE | 64 (49%) | 36 (50%) | 9 (47%) | 19 (48%) | 0.546 |

| Arrhythmia | 33 (35%) | 18 (25%) | 7 (37%) | 8 (21%) | 0.207 |

| FALD | 12 (9%) | 4 (5%) | 1 (5%) | 7 (18%) | 0.017 |

| Medications | |||||

| Anticoagulation | 125 (96%) | 69 (96%) | 17 (89%) | 39 (100%) | 0.774 |

| ACE inhibitor | 20 (15%) | 8 (11%) | 1 (5%) | 11 (28%) | 0.010 |

| Diuretics | 14 (11%) | 8 (11%) | 0 | 6 (15%) | 0.208 |

| Pulmonary vasodilation | 10 (8%) | 6 (8%) | 0 | 4 (10%) | 0.347 |

| Beta-Blocker | 20 (15%) | 10 (14%) | 2 (11%) | 8 (21%) | 0.211 |

| Ventricular Function | |||||

| 1/2/3 | 67/57/6 | 47/24/1 | 8/9/2 | 12/24/3 | 0.009 |

| AVV Regurgitation | |||||

| 0/1/2/3 | 35/61/31/3 | 25/33/13/1 | 4/11/3/1 | 6/17/15/1 | 0.044 |

| NT-proBNP (ng/L) | 248.7 (10–4140) | 171.8 (10–1030) | 195.9 (29–1550) | 412.8 (39–4140) | 0.004 |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 0.7 (0.3–1.9) | 0.7 (0.4–1.9) | 0.8 (0.5–1.1) | 0.70 (0.3–1.9) | 0.244 |

| BUN (mg/dL) | 30.6 (3.1–267.2) | 28.5 (10.2–73.4) | 28.2 (16.7–48.2) | 36.1 (3.1–267.0) | 0.999 |

| AST (U/L) | 33.4 (12.5–177.3) | 29.9 (12.5–61.9) | 29.9 (18.3–47.1) | 42.1 (16.1–177.3) | 0.103 |

| ALT(U/L) | 29.9 (9.5–114.0) | 27.9 (9.5–53.2) | 30.2 (12.8–55.9) | 33.2 (11.8–114.1) | 0.883 |

| GGT(U/L) | 74.8 (23.0–421.0) | 62.7 (24.8–210.2) | 89.0 (26.9–203.3) | 90.8 (23.2–421.4) | 0.120 |

| Protein (g/dL) | 7.2 (3.6–8.8) | 7.2 (3.6–8.8) | 7.4 (7.1–7.8) | 7.1 (4.8–8.5) | 0.256 |

| Albumin (g/L) | 44.8 (17.1–53.7) | 44.5 (17.1–53.7) | 46.6 (38.1–49.5) | 44.6 (26.7–51.1) | 0.435 |

| Cardiac Interventions | Non-HLHS (n = 91) | HLHS (n = 39) |

|---|---|---|

| LPA dilation/LPA stenting | 9 (9.9%) | 4 (10.3%) |

| Closure of venovenous or aorto-pulmonary collaterals | 13 (14.3%) | 4 (10.3%) |

| Aortic arch stenosis | 1 (1.1%) | 4 (10.3%) |

| TCPC tunnel ballon angioplasty/stenting | 3 (3.3%) | - |

| Local lysis of pulmonary artery thrombus | 1 (1.1%) | - |

| Total | 27 (29.7%) | 12 (30.9%) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bambul Heck, P.; Schüttler, A.; Hager, A.; Ono, M.; Hörer, J.; Ewert, P.; Tutarel, O. Outcome of Fontan Patients After Reaching Adolescence: The Impact of Hypoplastic Left Heart Syndrome. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 8611. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238611

Bambul Heck P, Schüttler A, Hager A, Ono M, Hörer J, Ewert P, Tutarel O. Outcome of Fontan Patients After Reaching Adolescence: The Impact of Hypoplastic Left Heart Syndrome. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(23):8611. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238611

Chicago/Turabian StyleBambul Heck, Pinar, Andreas Schüttler, Alfred Hager, Masamichi Ono, Jürgen Hörer, Peter Ewert, and Oktay Tutarel. 2025. "Outcome of Fontan Patients After Reaching Adolescence: The Impact of Hypoplastic Left Heart Syndrome" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 23: 8611. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238611

APA StyleBambul Heck, P., Schüttler, A., Hager, A., Ono, M., Hörer, J., Ewert, P., & Tutarel, O. (2025). Outcome of Fontan Patients After Reaching Adolescence: The Impact of Hypoplastic Left Heart Syndrome. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(23), 8611. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238611