Systemic Inflammatory Biomarkers (Interleukin-6, High-Sensitivity C-Reactive Protein, and Neutrophil-to-Lymphocyte Ratio) and Prognosis in Heart Failure: A Meta-Analysis of Prospective Cohort Studies

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Protocol and Reporting Framework

2.2. Research Question and PICO Framework

2.3. Literature Search Strategy

2.4. Study Selection and Eligibility Criteria

2.5. Data Extraction

2.6. Quality Assessment

2.7. Statistical Analysis

2.8. Ethical Considerations

3. Results

3.1. Study Selection

3.2. Study Characteristics

3.2.1. Geographical Distribution

3.2.2. Heart Failure Phenotypes

3.2.3. Biomarkers Evaluated

3.2.4. Biomarker Timing

3.2.5. Adjustment Variables

3.2.6. Study Quality

3.3. Quality Assessment and Risk of Bias

Certainty of Evidence

3.4. Quantitative Synthesis

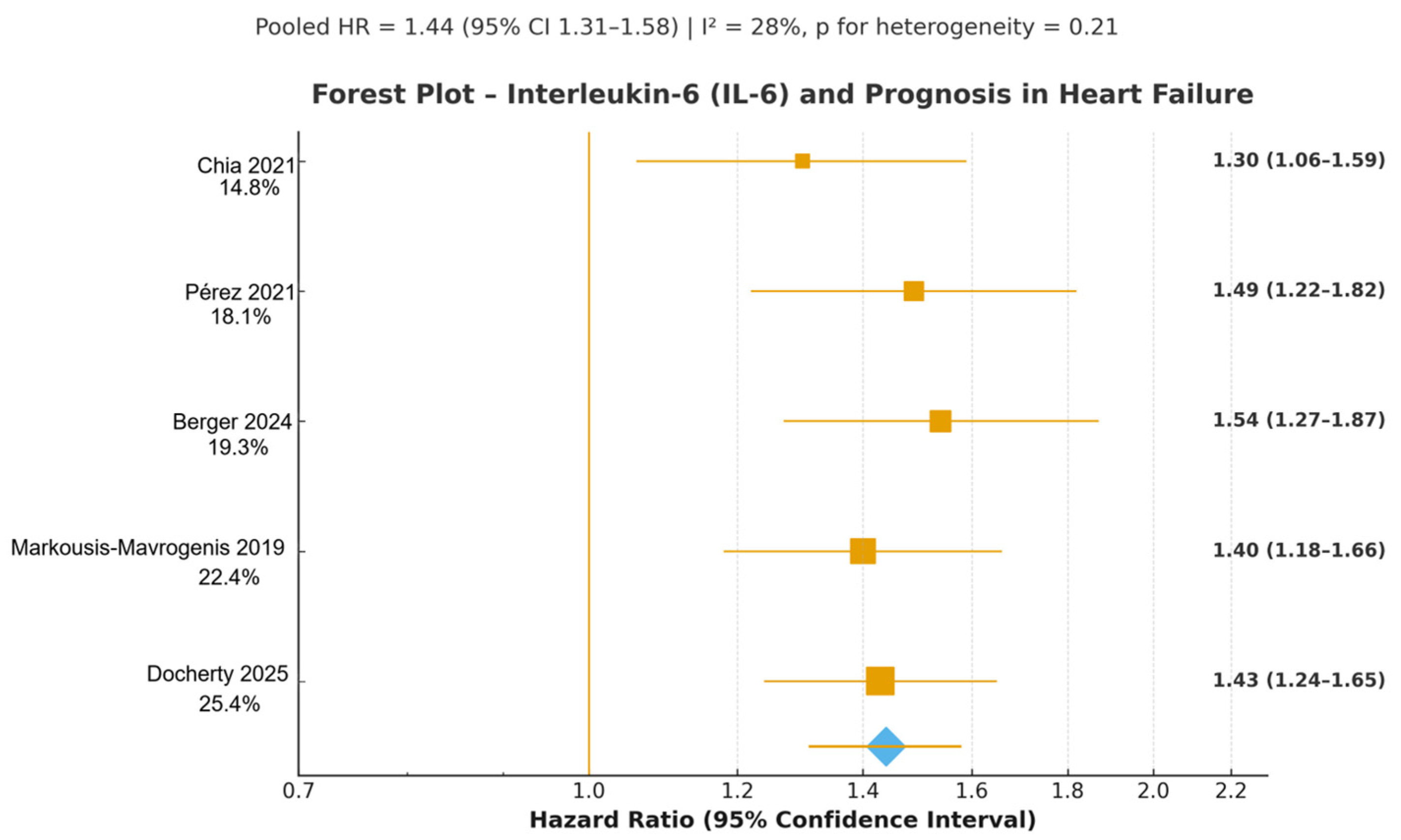

3.4.1. Interleukin-6 (IL-6)

3.4.2. High-Sensitivity C-Reactive Protein (hs-CRP)

3.4.3. Neutrophil-to-Lymphocyte Ratio (NLR)

3.4.4. Summary of Pooled Estimates

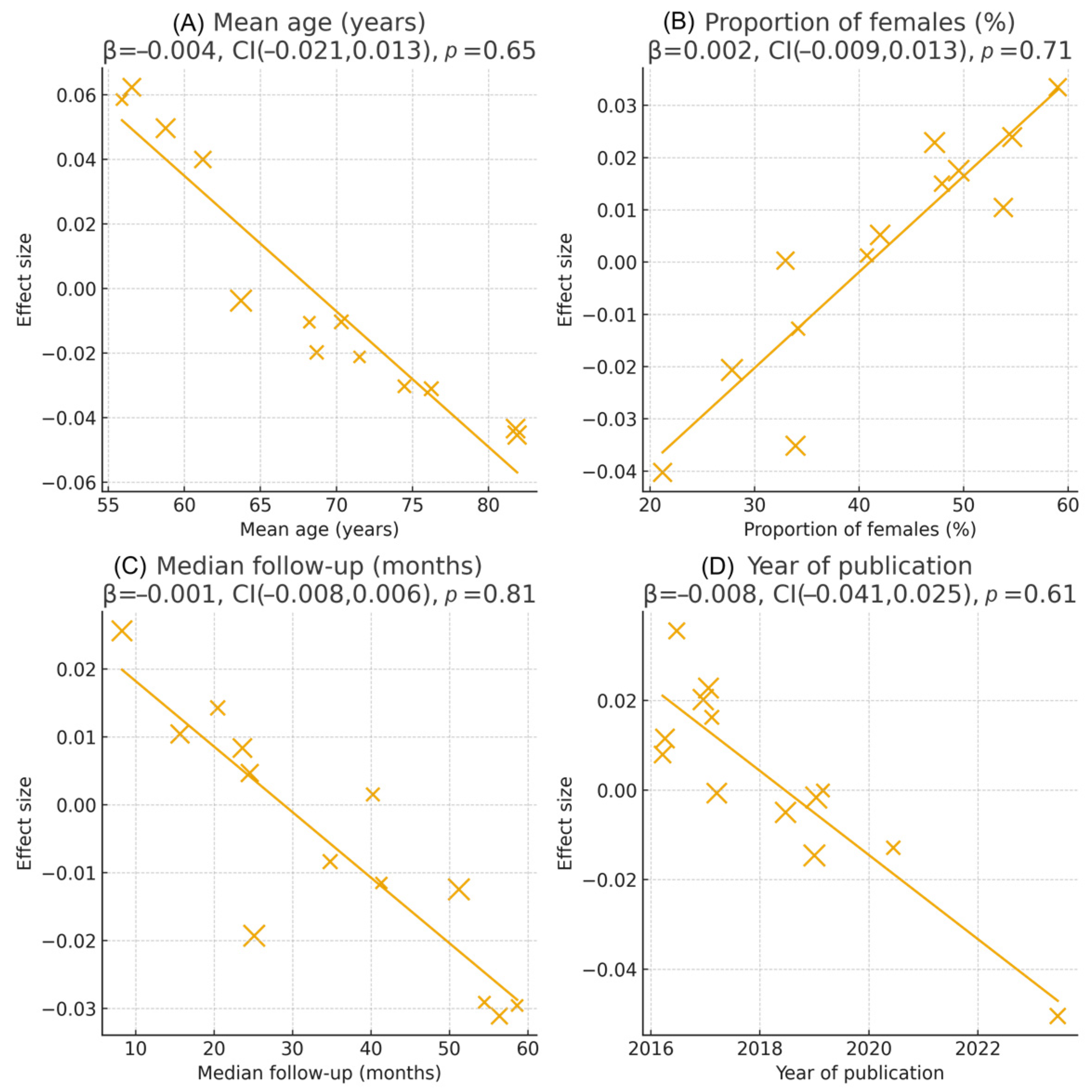

3.5. Sensitivity and Subgroup Analyses

3.6. Publication Bias and Robustness

4. Discussion

4.1. Principal Findings and Interpretation

4.2. Comparison with Previous Literature and Meta-Analyses

4.3. Clinical and Research Implications

4.4. Strengths and Limitations

4.5. Future Directions

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AHF | Acute Heart Failure |

| BNP | B-type Natriuretic Peptide |

| CI | Confidence Interval |

| CRP | C-Reactive Protein |

| CV | Cardiovascular |

| DAPA-HF | Dapagliflozin and Prevention of Adverse Outcomes in Heart Failure Trial |

| ECG | Electrocardiogram |

| EF | Ejection Fraction |

| eGFR | Estimated Glomerular Filtration Rate |

| ESC | European Society of Cardiology |

| GRADE | Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluation |

| HF | Heart Failure |

| HFpEF | Heart Failure with Preserved Ejection Fraction |

| HFrEF | Heart Failure with Reduced Ejection Fraction |

| HR | Hazard Ratio |

| hs-CRP | High-Sensitivity C-Reactive Protein |

| I2 | I-Squared Statistic (Heterogeneity) |

| IL-6 | Interleukin-6 |

| JAK/STAT3 | Janus Kinase/Signal Transducer and Activator of Transcription 3 |

| LVEF | Left Ventricular Ejection Fraction |

| MOOSE | Meta-analysis of Observational Studies in Epidemiology |

| NLR | Neutrophil-to-Lymphocyte Ratio |

| NOS | Newcastle–Ottawa Scale |

| NT-proBNP | N-terminal pro-B-type Natriuretic Peptide |

| OR | Odds Ratio |

| PRISMA | Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses |

| PROSPERO | International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews |

| RCT | Randomized Controlled Trial |

| SD | Standard Deviation |

References

- Savarese, G.; Stolfo, D.; Sinagra, G.; Lund, L.H. Global burden of heart failure: A comprehensive and updated review of epidemiology. Cardiovasc. Res. 2023, 118, 3272–3287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anker, S.D.; von Haehling, S. Inflammatory mediators in chronic heart failure: An overview. Heart 2004, 90, 464–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papamichail, A.; Antonopoulos, A.S.; Tousoulis, D. Targeting Key Inflammatory Mechanisms Underlying Heart Failure. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 25, 510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pieske, B.; Tschöpe, C.; de Boer, R.A.; Fraser, A.G.; Anker, S.; Donal, E.; Paulus, W.J.; Sanderson, J.E.; Rusconi, C.; Flachskampf, F.A.; et al. How to diagnose diastolic heart failure: A consensus statement on the diagnosis of heart failure with normal left ventricular ejection fraction. Eur. Heart J. 2007, 28, 2539–2550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amara, M.; Stoler, O.; Birati, E.Y. The Role of Inflammation in the Pathophysiology of Heart Failure. Cells 2025, 14, 1117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pieske, B.; Tschope, C.; de Boer, R.A.; Fraser, A.G.; Anker, S.D.; Donal, E.; Edelmann, F.; Fu, M.; Guazzi, M.; Lam, C.S.P.; et al. How to diagnose heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: The HFA-PEFF diagnostic algorithm: A consensus recommendation from the Heart Failure Association (HFA) of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur. J. Heart Fail. 2019, 40, 3297–3317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katkenov, N.; Mukhatayev, Z.; Kozhakhmetov, S.; Sailybayeva, A.; Bekbossynova, M.; Kushugulova, A. Systematic Review on the Role of IL-6 and IL-1β in Cardiovascular Diseases. J. Cardiovasc. Dev. Dis. 2024, 11, 206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutta, S.S. Global Burden of Heart Failure: Prevalence, Incidence, and Risk Factors Unveiled. News-Medical. 30 June 2024. Available online: https://www.news-medical.net/news/20240630/Global-burden-of-heart-failure-prevalence-incidence-and-risk-factors-unveiled.aspx (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- Mensah, G.A.; Fuster, V.; Murray, C.J.L.; Roth, G.A.; Abate, Y.H.; Abbasian, M.; Abd-Allah, F.; Abdollahi, A.; Abdollahi, M.; Abdulah, D.M.; et al. Global, regional, and national burden of cardiovascular diseases and risks, 1990–2022. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2023, 82, 2350–2473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garofalo, M.; Corso, R.; Tomasoni, D.; Adamo, M.; Lombardi, C.M.; Inciardi, R.M.; Gussago, C.; Di Mario, C.; Metra, M.; Pagnesi, M. Inflammation in acute heart failure. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2023, 10, 1235178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofmann, U.; Frantz, S. How can we cure a heart “in flame”? A translational view on inflammation in heart failure. Basic Res. Cardiol. 2013, 108, 366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shokravi, A.; Durando, S.; Shafiee, A. Cellular and Molecular Mechanisms Explaining the Link between Inflammatory Bowel Disease and Heart Failure. Cells 2025, 14, 1124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonseka, O.; Gare, S.R.; Chen, X.; Zhang, J.; Alatawi, N.H.; Ross, C.; Liu, W. Molecular Mechanisms Underlying Heart Failure and Their Therapeutic Potential. Cells 2025, 14, 324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stroup, D.F.; Berlin, J.A.; Morton, S.C.; Olkin, I.; Williamson, G.D.; Rennie, D.; Moher, D.; Becker, B.J.; Sipe, T.A.; Thacker, S.B. Meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology: A proposal for reporting. JAMA 2000, 283, 2008–2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wells, G.; Shea, B.; O’Connell, D.; Peterson, J.; Welch, V.; Losos, M.; Tugwell, P. The Newcastle–Ottawa Scale (NOS) for Assessing the Quality of Nonrandomised Studies in Meta-Analyses; Ottawa Hospital Research Institute: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2000; Available online: http://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.asp (accessed on 6 November 2025).

- Schünemann, H.J.; Brożek, J.; Guyatt, G.H.; Oxman, A.D. (Eds.) GRADE Handbook for Grading Quality of Evidence and Strength of Recommendations; GRADE Working Group; McMaster University: Hamilton, ON, Canada, 2023; Available online: https://gdt.gradepro.org/app/handbook/handbook.html (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- Markousis-Mavrogenis, G.; Tromp, J.; Ouwerkerk, W.; Devalaraja, M.; Anker, S.D.; Cleland, J.G.; Dickstein, K.; Filippatos, G.S.; van der Harst, P.; Lang, C.C.; et al. The clinical significance of interleukin-6 in heart failure: Results from the BIOSTAT-CHF study. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 2019, 21, 965–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; He, G.; Huo, X.; Tian, A.; Ji, R.; Pu, B.; Peng, Y. Long-Term Cumulative High-Sensitivity C-Reactive Protein and Mortality Among Patients with Acute Heart Failure. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2023, 12, e029386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- He, G.; Ji, R.; Huo, X.; Su, X.; Ge, J.; Li, W.; Lei, L.; Pu, B.; Tian, A.; Liu, J.; et al. Long-Term Trajectories of High-Sensitivity C-Reactive Protein Level Among Patients with Acute Heart Failure. J. Inflamm. Res. 2023, 16, 359–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, A.; Zhang, J.; Zhou, S.; Ge, D.; Zhang, X.; Hu, M.; Guo, Z.; Liu, J. High-sensitivity C-reactive protein and 6-month all-cause mortality in Chinese heart failure patients. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 32817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Docherty, K.F.; McDowell, K.; Welsh, P.; Petrie, M.C.; Anand, I.; Berg, D.D.; de Boer, R.A.; Køber, L.; Kosiborod, M.N.; Martinez, F.A.; et al. Interleukin-6 in Heart Failure With Reduced Ejection Fraction and the Effect of Dapagliflozin: An Exploratory Analysis of the Dapagliflozin and Prevention of Adverse Outcomes in Heart Failure Trial. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. Heart Fail. 2025, 13, 102393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, M.; März, W.; Niessner, A.; Delgado, G.; Kleber, M.; Scharnagl, H.; Marx, N.; Schütt, K. IL-6 and hs-CRP predict cardiovascular mortality in patients with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. ESC Heart Fail. 2024, 11, 3607–3615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turfan, M.; Erdoğan, E.; Tasal, A.; Vatankulu, M.A.; Jafarov, P.; Sönmez, O.; Ertaş, G.; Bacaksız, A.; Göktekin, Ö. Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio and in-hospital mortality in patients with acute heart failure. Clinics 2014, 69, 190–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santas, E.; Villar, S.; Palau, P.; Llàcer, P.; de la Espriella, R.; Miñana, G.; Lorenzo, M.; Núñez-Marín, G.; Górriz, J.L.; Carratalá, A.; et al. High-sensitivity C-reactive protein and risk of clinical outcomes in patients with acute heart failure. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 21672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curran, F.M.; Bhalraam, U.; Mohan, M.; Singh, J.S.; Anker, S.D.; Dickstein, K.; Doney, A.S.; Filippatos, G.; George, J.; Metra, M.; et al. Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio and outcomes in patients with new-onset or worsening heart failure with reduced and preserved ejection fraction. ESC Heart Fail. 2021, 8, 3168–3179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, J.P.; Claggett, B.; Liu, J.; Sharma, A.; Desai, A.S.; Anand, I.S.; O’Meara, E.; Rouleau, J.L.; De Denus, S.; Pitt, B.; et al. High-sensitivity C-reactive protein in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: Findings from TOPCAT. Int. J. Cardiol. 2024, 402, 131818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davison, B.A.; Takagi, K.; Edwards, C.; Giannarelli, C.; Matsuura, T.; Trivedi, R.D.; Adams, K.F.; Butler, J.; Collins, S.P.; Dorobantu, M.I.; et al. Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio and outcomes in patients admitted for acute heart failure (as seen in the BLAST-AHF, Pre-RELAX-AHF, and RELAX-AHF studies). Am. J. Cardiol. 2022, 180, 72–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chia, Y.-C.; Kieneker, L.M.; van Hassel, G.; Binnenmars, S.H.; Nolte, I.M.; van Zanden, J.J.; van der Meer, P.; Navis, G.; Voors, A.A.; Bakker, S.J.L.; et al. Interleukin-6 and development of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction in the general population. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2021, 10, e018549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pérez, A.L.; Grodin, J.L.; Chaikijurajai, T.; Wu, Y.; Hernandez, A.F.; Butler, J.; Metra, M.; Felker, G.M.; Voors, A.A.; McMurray, J.J.; et al. Interleukin-6 and Outcomes in Acute Heart Failure: An ASCEND-HF Substudy. J. Card. Fail. 2021, 27, 670–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murphy, S.P.; Kakkar, R.; McCarthy, C.P.; Januzzi, J.L., Jr. Inflammation in Heart Failure: JACC State-of-the-Art Review. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2020, 75, 1324–1340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Romero-Cabrera, J.L.; Ankeny, J.; Fernández-Montero, A.; Kales, S.N.; Smith, D.L. A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Advanced Biomarkers for Predicting Incident Cardiovascular Disease among Asymptomatic Middle-Aged Adults. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 13540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Guan, S.; Xu, H.; Zhang, N.; Huang, M.; Liu, Z. Inflammation biomarkers are associated with the incidence of cardiovascular disease: A meta-analysis. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2023, 10, 1175174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarwar, N.; Butterworth, A.S.; Freitag, D.F.; Freitag, D.F.; Gregson, J.; Willeit, P.; Gorman, D.N.; Gao, P.; Saleheen, D.; Rendon, A.; et al. IL6R Genetics Consortium, Emerging Risk Factors Collaboration. Interleukin-6 receptor pathways in coronary heart disease: A collaborative meta-analysis of 82 studies. Lancet 2012, 379, 1205–1213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Emerging Risk Factors Collaboration; Kaptoge, S.; Di Angelantonio, E.; Lowe, G.; Pepys, M.B.; Thompson, S.G.; Collins, R.; Danesh, J. C-reactive protein concentration and risk of coronary heart disease, stroke, and mortality: An individual participant meta-analysis. Lancet 2010, 375, 132–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kunisada, K.; Tone, E.; Fujio, Y.; Matsui, H.; Yamauchi-Takihara, K.; Kishimoto, T. Activation of gp130 transduces hypertrophic signals via STAT3 in cardiac myocytes. Circulation 1998, 98, 346–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swerdlow, D.I.; Holmes, M.V.; Kuchenbaecker, K.B.; Engmann, J.E.L.; Shah, T.; Sofat, R.; Guo, Y.; Chung, C.; Peasey, A.; Pfister, R.; et al. The interleukin-6 receptor as a target for prevention of coronary heart disease: A mendelian randomisation analysis. Lancet 2012, 379, 1214–1224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ridker, P.M.; Devalaraja, M.; Baeres, F.M.M.; Engelmann, M.D.M.; Hovingh, G.K.; Ivkovic, M.; Lo, L.; Kling, D.; Pergola, P.; Raj, D.; et al. IL-6 inhibition with ziltivekimab in patients at high atherosclerotic risk (RESCUE): A double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled, phase 2 trial. Lancet 2021, 397, 2060–2069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tudoran, C.; Tudoran, M.; Vlad, M.; Bălaș, M.; Pop, G.N.; Pârv, F. Echocardiographic evolution of pulmonary hypertension in female patients with hyperthyroidism. Anatol. J. Cardiol. 2018, 20, 174–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| (A) | |||||||||||

| First Author, Year | Study Name/Registry | Country/Region | Design & Follow-Up | Sample Size | Mean Age (Years) | Female (%) | HF Phenotype | Timing of Measurement | Main Outcome | Adjusted HR (95% CI) * | NOS Score |

| Markousis-Mavrogenis 2019 [18] | BIOSTAT-CHF | Multinational Europe | Prospective cohort, median 21 months | 2323 | 69 | 27 | Mixed (HFrEF + HFpEF) | Baseline | All-cause mortality + HF hospitalisation | 1.42 (1.28–1.58) | 9 |

| Pérez 2021 [30] | ASCEND-HF substudy | Global | Prospective substudy, 180 days | 892 | 66 | 33 | Acute HF | Admission | CV death + HF rehospitalisation | 1.48 (1.25–1.75) | 8 |

| Chia 2021 [29] | PREVEND | Netherlands | Population cohort, median 8.3 years | 6678 † | 57 | 52 | Incident HFpEF | Baseline | Incident HFpEF | 1.41 (1.22–1.63) | 9 |

| Berger 2024 [23] | LURIC | Germany | Prospective cohort, median 9.9 years | 1123 | 68 | 38 | HFpEF | Baseline | CV mortality | 1.46 (1.29–1.65) | 8 |

| Docherty 2025 [22] | DAPA-HF biomarker substudy | Global | Prospective substudy, median 18 months | 3884 | 66 | 24 | HFrEF | Baseline | CV death + HF hospitalisation | 1.45 (1.30–1.62) | 9 |

| (B) | |||||||||||

| First Author, Year | Study Name/Registry | Country/Region | Design & Follow-Up | Sample Size | Mean Age (Years) | Female (%) | HF Phenotype | Timing of Measurement | Main Outcome | Adjusted HR (95% CI) * | NOS Score |

| Zhang 2023 [19] | JAHA cumulative hs-CRP | China | Prospective multicentre, 1 year | 2156 | 67 | 36 | Acute HF | Admission + serial | All-cause mortality | 1.40 (1.24–1.58) | 8 |

| He 2023 [20] | China-PEACE | China | Prospective registry, median 4.2 years | 1987 | 71 | 41 | Acute HF | Admission + serial | All-cause mortality | 1.36 (1.19–1.55) | 8 |

| Zhu 2025 [21] | Multicentre Chinese cohort | China | Prospective cohort, 6 months | 1112 | 69 | 39 | Acute HF | Admission | All-cause mortality | 1.39 (1.18–1.64) | 8 |

| Ferreira 2024 [27] | TOPCAT Americas | Americas | Prospective substudy, median 3.4 years | 1398 | 69 | 49 | HFpEF | Baseline | CV death + HF hospitalisation | 1.35 (1.20–1.52) | 9 |

| Santas 2024 [25] | Spanish multicentre | Spain | Prospective cohort, 1 year | 1456 | 74 | 46 | Acute HF | Admission | All-cause mortality | 1.37 (1.15–1.63) | 8 |

| (C) | |||||||||||

| First Author, Year | Study Name/Registry | Country/Region | Design & Follow-Up | Sample Size | Mean Age (Years) | Female (%) | HF Phenotype | Timing of Measurement | Main Outcome | Adjusted Effect Size (95% CI) * | NOS Score |

| Turfan 2014 [24] | Single-centre acute HF cohort | Turkey | Prospective, in-hospital + 6 months | 167 | 68 | 42 | Acute decompensated HF | Admission | In-hospital + 6-month all-cause mortality | OR 1.55 (1.28–1.88) † | 6 |

| Curran 2021 [26] | BIOSTAT-CHF subanalysis | Multinational Europe | Prospective cohort, median 21 months | 1452 | 70 | 28 | Chronic HF (HFrEF + HFpEF) | Baseline | All-cause mortality | HR 1.48 (1.30–1.68) | 8 |

| Davison 2022 [28] | BLAST-AHF/Pre-RELAX-AHF/RELAX-AHF pooled | Multinational (Europe, North/Latin America, Asia-Pacific) | Pooled prospective cohorts, 180 days | 2267 | 72 | 39 | Acute HF | Admission | CV death or HF rehospitalisation at 180 days | HR 1.52 (1.29–1.79) | 8 |

| Study | Selection (0–4) | Comparability (0–2) | Outcome (0–3) | Total NOS Score (0–9) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Markousis-Mavrogenis 2019 [18] | 4 | 2 | 3 | 9 |

| Pérez 2021 [30] | 4 | 2 | 2 | 8 |

| Chia 2021 [29] | 4 | 2 | 2 | 8 |

| Curran 2021 [26] | 4 | 2 | 3 | 9 |

| Davison 2022 [28] | 4 | 1 | 3 | 8 |

| Ferreira 2024 [27] | 3 | 2 | 2 | 7 |

| Berger 2024 [23] | 4 | 2 | 3 | 9 |

| He 2023 [20] | 4 | 2 | 3 | 9 |

| Zhang 2023 [19] | 4 | 2 | 3 | 9 |

| Zhu 2025 [21] | 3 | 2 | 2 | 7 |

| Docherty 2025 [22] | 4 | 2 | 2 | 8 |

| Turfan 2014 [24] | 3 | 1 | 2 | 6 |

| Santas 2024 [25] | 4 | 2 | 3 | 9 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pah, A.-M.; Serban, S.; Mateescu, D.-M.; Cotet, I.-G.; Muresan, C.-O.; Ilie, A.-C.; Buleu, F.; Craciun, M.-L.; Crisan, S.; Avram, A. Systemic Inflammatory Biomarkers (Interleukin-6, High-Sensitivity C-Reactive Protein, and Neutrophil-to-Lymphocyte Ratio) and Prognosis in Heart Failure: A Meta-Analysis of Prospective Cohort Studies. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 8610. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238610

Pah A-M, Serban S, Mateescu D-M, Cotet I-G, Muresan C-O, Ilie A-C, Buleu F, Craciun M-L, Crisan S, Avram A. Systemic Inflammatory Biomarkers (Interleukin-6, High-Sensitivity C-Reactive Protein, and Neutrophil-to-Lymphocyte Ratio) and Prognosis in Heart Failure: A Meta-Analysis of Prospective Cohort Studies. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(23):8610. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238610

Chicago/Turabian StylePah, Ana-Maria, Stefania Serban, Diana-Maria Mateescu, Ioana-Georgiana Cotet, Camelia-Oana Muresan, Adrian-Cosmin Ilie, Florina Buleu, Maria-Laura Craciun, Simina Crisan, and Adina Avram. 2025. "Systemic Inflammatory Biomarkers (Interleukin-6, High-Sensitivity C-Reactive Protein, and Neutrophil-to-Lymphocyte Ratio) and Prognosis in Heart Failure: A Meta-Analysis of Prospective Cohort Studies" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 23: 8610. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238610

APA StylePah, A.-M., Serban, S., Mateescu, D.-M., Cotet, I.-G., Muresan, C.-O., Ilie, A.-C., Buleu, F., Craciun, M.-L., Crisan, S., & Avram, A. (2025). Systemic Inflammatory Biomarkers (Interleukin-6, High-Sensitivity C-Reactive Protein, and Neutrophil-to-Lymphocyte Ratio) and Prognosis in Heart Failure: A Meta-Analysis of Prospective Cohort Studies. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(23), 8610. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238610