Impact of a Medical–Government Conflict on Healthcare Workers’ Mental Health in a Single Tertiary Hospital

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Population

2.2. Period Classification

2.3. Measurement Tools

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

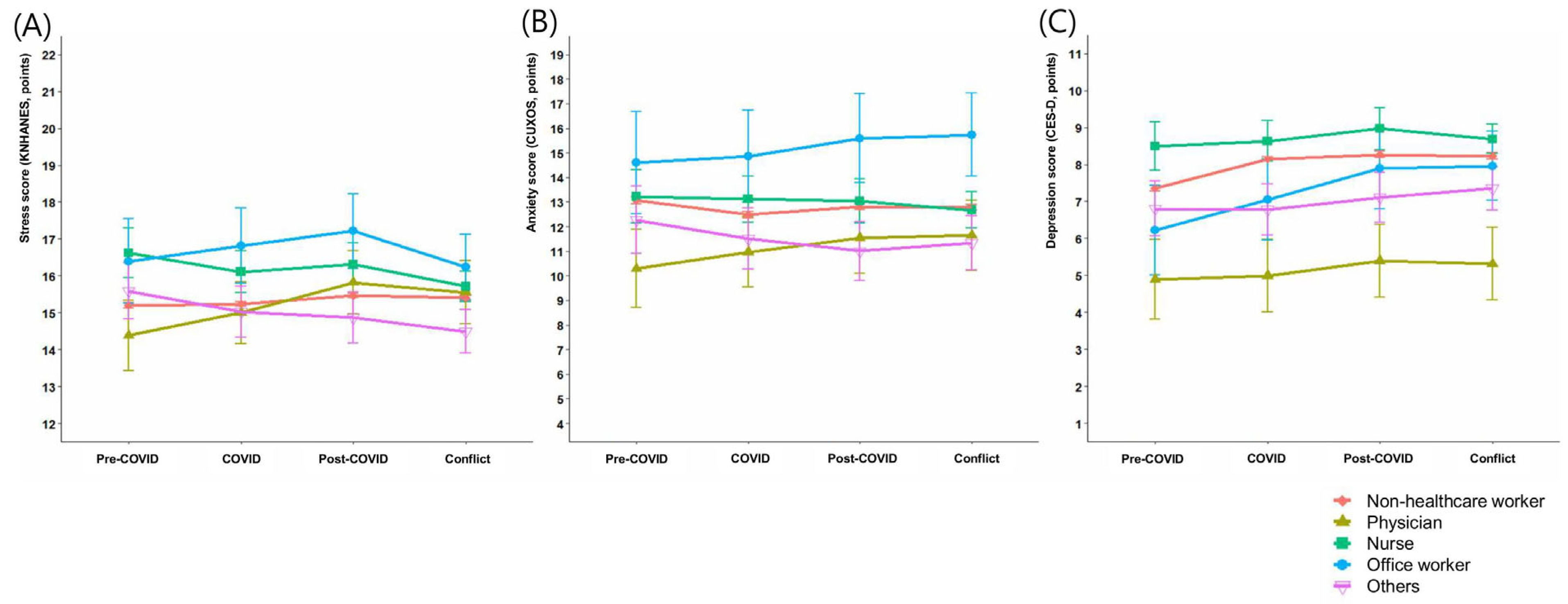

3.1. Temporal Changes in Mental Health Status by Occupation

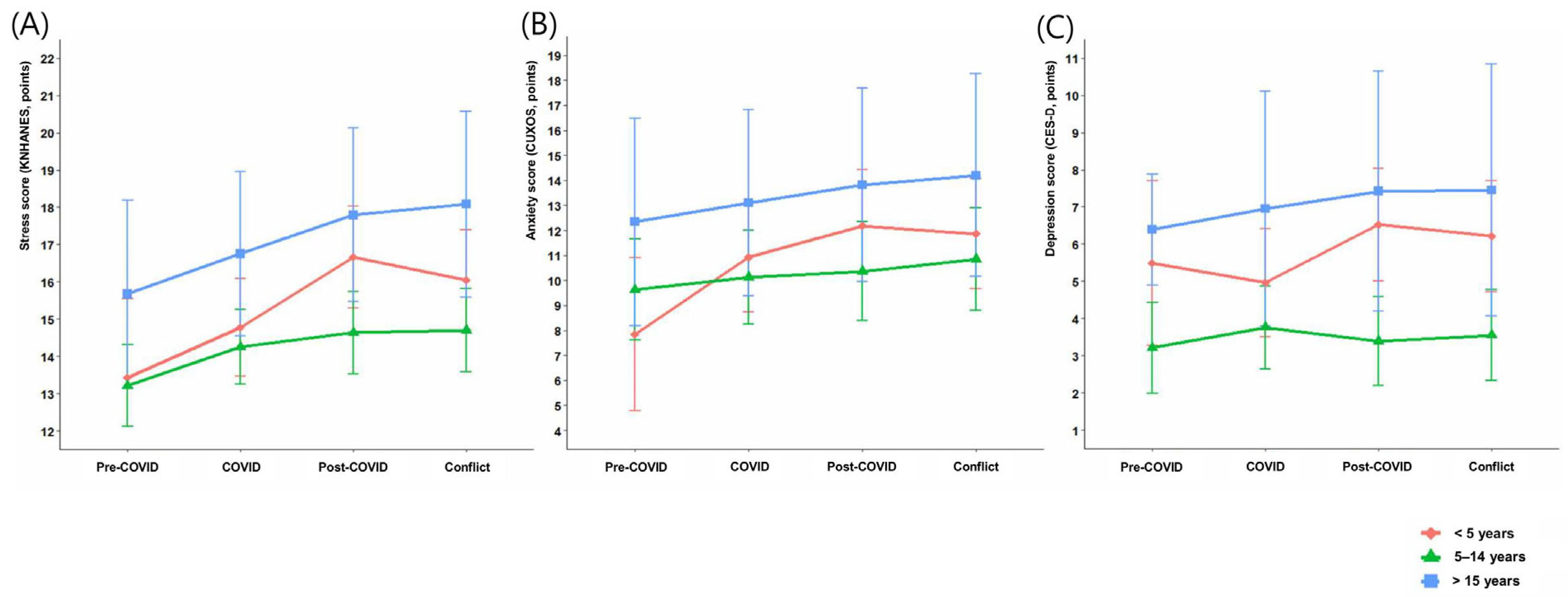

3.2. Subgroup Analyses of Attending Physicians by Sex, Age, and Length of Service

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| COVID | Coronavirus Disease 2019 |

| KNHANES | Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey |

| CES-D | Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale |

| CUXOS | Clinically Useful Anxiety Outcome Scale |

| BMI | Body Mass Index |

| MERS | Middle East Respiratory Syndrome |

References

- Hodkinson, A.; Zhou, A.; Johnson, J.; Geraghty, K.; Riley, R.; Zhou, A.; Panagopoulou, E.; Chew-Graham, C.A.; Peters, D.; Esmail, A.; et al. Associations of physician burnout with career engagement and quality of patient care: Systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ 2022, 378, e070442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yates, S.W. Physician Stress and Burnout. Am. J. Med. 2020, 133, 160–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McClafferty, H.; Brown, O.W.; Section on Integrative Medicine; Committee on Practice and Ambulatory Medicine; Vohra, S.; Bailey, M.L.; Becker, D.K.; Culbert, T.P.; Sibinga, E.M.; Zimmer, M.; et al. Physician Health and Wellness. Pediatrics 2022, 150, e2022059665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shanafelt, T.D.; West, C.P.; Sinsky, C.; Trockel, M.; Tutty, M.; Wang, H.; Carlasare, L.E.; Dyrbye, L.N. Changes in Burnout and Satisfaction With Work-Life Integration in Physicians and the General US Working Population Between 2011 and 2023. Mayo Clin. Proc. 2025, 100, 1142–1158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seo, Y.E.; Kim, H.C.; Yoo, S.Y.; Lee, K.U.; Lee, H.W.; Lee, S.H. Factors Associated with Burnout among Healthcare Workers during an Outbreak of MERS. Psychiatry Investig. 2020, 17, 674–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Um, D.H.; Kim, J.S.; Lee, H.W.; Lee, S.H. Psychological Effects on Medical Doctors from the Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS) Outbreak: A Comparison of Whether They Worked at the MERS Occurred Hospital or Not, and Whether They Participated in MERS Diagnosis and Treatment. J. Korean Neuropsychiatr. Assoc. 2017, 56, 28–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nayak, B.S.; Sahu, P.K.; Ramsaroop, K.; Maharaj, S.; Mootoo, W.; Khan, S.; Extravour, R.M. Prevalence and factors associated with depression, anxiety and stress among healthcare workers of Trinidad and Tobago during COVID-19 pandemic: A cross-sectional study. BMJ Open 2021, 11, e044397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myran, D.T.; Cantor, N.; Rhodes, E.; Pugliese, M.; Hensel, J.; Taljaard, M.; Talarico, R.; Garg, A.X.; McArthur, E.; Liu, C.W.; et al. Physician Health Care Visits for Mental Health and Substance Use During the COVID-19 Pandemic in Ontario, Canada. JAMA Netw. Open 2022, 5, e2143160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elbay, R.Y.; Kurtulmus, A.; Arpacioglu, S.; Karadere, E. Depression, anxiety, stress levels of physicians and associated factors in Covid-19 pandemics. Psychiatry Res. 2020, 290, 113130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ladwig, K.H.; Johar, H.; Miller, I.; Atasoy, S.; Goette, A. Covid-19 pandemic induced traumatizing medical job contents and mental health distortions of physicians working in private practices and in hospitals. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 5284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obeng Nkrumah, S.; Adu, M.K.; Agyapong, B.; da Luz Dias, R.; Agyapong, V.I.O. Prevalence and correlates of depression, anxiety, and burnout among physicians and postgraduate medical trainees: A scoping review of recent literature. Front. Public Health 2025, 13, 1537108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maunder, R.G.; Heeney, N.D.; Jeffs, L.P.; Wiesenfeld, L.A.; Hunter, J.J. A longitudinal study of hospital workers’ mental health from fall 2020 to the end of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2023. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 26137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Umbetkulova, S.; Kanderzhanova, A.; Foster, F.; Stolyarova, V.; Cobb-Zygadlo, D. Mental Health Changes in Healthcare Workers During COVID-19 Pandemic: A Systematic Review of Longitudinal Studies. Eval. Health Prof. 2024, 47, 11–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petrović, J.; Dimić, S.; Ljubojević, S. Attitudes of Defence and Security Sector Members’ Towards Urban Public Transport Service Quality During COVID-19 State of Emergency. Теме 2021, 45, 1311–1327. [Google Scholar]

- McVicar, A. Workplace stress in nursing: A literature review. J. Adv. Nurs. 2003, 44, 633–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, B.Y.Q.; Chew, N.W.S.; Lee, G.K.H.; Jing, M.; Goh, Y.; Yeo, L.L.L.; Zhang, K.; Chin, H.K.; Ahmad, A.; Khan, F.A.; et al. Psychological Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Health Care Workers in Singapore. Ann. Intern. Med. 2020, 173, 317–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, J.; Ma, S.; Wang, Y.; Cai, Z.; Hu, J.; Wei, N.; Wu, J.; Du, H.; Chen, T.; Li, R.; et al. Factors Associated With Mental Health Outcomes Among Health Care Workers Exposed to Coronavirus Disease 2019. JAMA Netw. Open 2020, 3, e203976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- West, C.P.; Dyrbye, L.N.; Shanafelt, T.D. Physician burnout: Contributors, consequences and solutions. J. Intern. Med. 2018, 283, 516–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheon, Y.; Park, J.; Jeong, B.Y.; Park, E.Y.; Oh, J.K.; Yun, E.H.; Lim, M.K. Factors associated with psychological stress and distress among Korean adults: The results from Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 15134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, M.J.; Kim, K.H. Use of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression (CES-D) Scale in Korea. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 1998, 186, 304–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeon, S.W.; Han, C.; Ko, Y.H.; Yoon, S.; Pae, C.U.; Choi, J.; Kim, J.M.; Yoon, H.K.; Lee, H.; Patkar, A.A.; et al. A Korean validation study of the Clinically Useful Anxiety Outcome Scale: Comorbidity and differentiation of anxiety and depressive disorders. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0179247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Slopen, N.; Kontos, E.Z.; Ryff, C.D.; Ayanian, J.Z.; Albert, M.A.; Williams, D.R. Psychosocial stress and cigarette smoking persistence, cessation, and relapse over 9–10 years: A prospective study of middle-aged adults in the United States. Cancer Causes Control. 2013, 24, 1849–1863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomiyama, A.J. Stress and Obesity. Ann. Rev. Psychol. 2019, 70, 703–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schisterman, E.F.; Cole, S.R.; Platt, R.W. Overadjustment bias and unnecessary adjustment in epidemiologic studies. Epidemiology 2009, 20, 488–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peck, J.A.; Porter, T.H. Pandemics and the Impact on Physician Mental Health: A Systematic Review. Med. Care Res. Rev. 2022, 79, 772–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yun, J.Y.; Myung, S.J.; Kim, K.S. Associations among the workplace violence, burnout, depressive symptoms, suicidality, and turnover intention in training physicians: A network analysis of nationwide survey. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 16804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.L.; Dai, J.W.; Li, X.W.; Lin, Y.C.; Wang, C.H. Exploring burnout, resilience and the coping strategies among critical healthcare professionals in post-COVID Taiwan. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 33144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanz, J.A.-O.; Bruk-Lee, V. Resilience as a moderator of the indirect effects of conflict and workload on job outcomes among nurses. J. Adv. Nurs. 2017, 73, 2973–2986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, J.-Y.; Kim, G.-M.; Kim, E.-J. Factors Associated with Job Stress among Hospital Nurses: A Meta-Correlation Analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 5792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norful, A.A.-O.X.; Albloushi, M.A.-O.; Zhao, J.; Gao, Y.; Castro, J.; Palaganas, E.; Magsingit, N.S.; Molo, J.; Alenazy, B.A.; Rivera, R. Modifiable work stress factors and psychological health risk among nurses working within 13 countries. J. Nurs. Scholarsh. 2024, 56, 742–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Hwang, S.; Kwon, K.T.; Nam, E.; Chung, U.S.; Kim, S.W.; Chang, H.H.; Kim, Y.; Bae, S.; Shin, J.Y.; et al. Prevalence and Associated Factors of Depression and Anxiety Among Healthcare Workers During the Coronavirus Disease 2019 Pandemic: A Nationwide Study in Korea. J. Korean Med. Sci. 2024, 39, e120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kogan, C.S.; Garcia-Pacheco, J.A.; Rebello, T.J.; Montoya, M.I.; Robles, R.; Khoury, B.; Kulygina, M.; Matsumoto, C.; Huang, J.; Medina-Mora, M.E.; et al. Longitudinal Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Stress and Occupational Well-Being of Mental Health Professionals: An International Study. Int. J. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2023, 26, 747–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aiken, L.H.; Lasater, K.B.; Sloane, D.M.; Pogue, C.A.; Fitzpatrick Rosenbaum, K.E.; Muir, K.J.; McHugh, M.D.; Consortium, U.S.C.W.S. Physician and Nurse Well-Being and Preferred Interventions to Address Burnout in Hospital Practice: Factors Associated With Turnover, Outcomes, and Patient Safety. JAMA Health Forum. 2023, 4, e231809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Z.; Chen, H.; Li, X.; Chen, S.; Wang, Z.; Yang, J.; Chen, Z.; Wang, X.; Tian, Y.; Zhou, J. Differences in the depression and burnout networks between doctors and nurses: Evidence from a network analysis. BMC Public Health 2024, 24, 1668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Young, K.P.; Kolcz, D.L.; Ferrand, J.; O’Sullivan, D.M.; Robinson, K. Healthcare Worker Mental Health and Wellbeing During COVID-19: Mid-Pandemic Survey Results. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 924913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subramanian, J.; Venkatakrishnan, R.T.; Cattamanchi, S.; Kumar, K.; Pugazhendhi, S.; Dharuman, K.K. Psychological Burden of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Healthcare Workers: A Comparative Study Across Sectors and Clinical Roles. Cureus 2025, 17, e91426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, C.; Corrado, M.; Fournier, K.; Bailey, T.; Haykal, K.A. Addressing the physician burnout epidemic with resilience curricula in medical education: A systematic review. BMC Med. Educ. 2021, 21, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angelopoulou, P.; Panagopoulou, E. Resilience interventions in physicians: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Appl. Psychol. Health Well-Being 2022, 14, 3–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buck, K.; Williamson, M.; Ogbeide, S.; Norberg, B. Family Physician Burnout and Resilience: A Cross-Sectional Analysis. Fam. Med. 2019, 51, 657–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- West, C.P.; Dyrbye, L.N.; Sinsky, C.; Trockel, M.; Tutty, M.; Nedelec, L.; Carlasare, L.E.; Shanafelt, T.D. Resilience and Burnout Among Physicians and the General US Working Population. JAMA Netw. Open 2020, 3, e209385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belkic, K. Toward better prevention of physician burnout: Insights from individual participant data using the MD-specific Occupational Stressor Index and organizational interventions. Front. Public Health 2025, 13, 1514706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Total (N = 56,137) | Non-Healthcare Worker (N = 54,122) | Physician (N = 237) | Nurse (N = 1113) | Office Worker (N = 234) | Other Staff (N = 431) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | <0.001 | ||||||

| Male | 41,407 (73.76) | 40,859 (75.49) | 166 (70.04) | 75 (6.74) | 88 (37.61) | 219 (50.81) | |

| Female | 14,730 (26.24) | 13,263 (24.51) | 71 (29.96) | 1038 (93.26) | 146 (62.39) | 212 (49.19) | |

| Age, mean ± SD | 40.04 ± 12.36 | 40.21 ± 12.43 | 42.97 ± 8.87 | 33.18 ± 8.22 | 38.02 ± 8.77 | 36.66 ± 8.86 | <0.001 |

| 20–29 | 13,344 (23.77) | 12,683 (23.43) | 3 (1.27) | 494 (44.38) | 43 (18.38) | 121 (28.07) | <0.001 |

| 30–39 | 18,967 (33.79) | 18,180 (33.59) | 108 (45.57) | 406 (36.48) | 103 (44.02) | 170 (39.44) | |

| 40–49 | 11,459 (20.41) | 11,086 (20.48) | 78 (32.91) | 144 (12.94) | 60 (25.64) | 91 (21.11) | |

| 50–59 | 8144 (14.51) | 7969 (14.72) | 35 (14.77) | 68 (6.11) | 24 (10.26) | 48 (11.14) | |

| ≧60 | 4223 (7.52) | 4204 (7.77) | 13 (5.49) | 1 (0.09) | 4 (1.71) | 1 (0.23) | |

| Length of service, mean ± SD | 10.34 ± 8.44 | 10.54 ± 8.43 | 4.84 ± 6.38 | 7.64 ± 7.93 | 11.70 ± 9.53 | 9.28 ± 8.64 | <0.001 |

| <5 yr | 7387 (13.16) | 6392 (11.81) | 164 (69.20) | 588 (52.83) | 76 (32.48) | 167 (38.75) | <0.001 |

| 5–14 yr | 9942 (17.71) | 9285 (17.16) | 49 (20.68) | 359 (32.26) | 83 (35.47) | 166 (38.52) | |

| ≧15 yr | 6366 (11.34) | 6003 (11.09) | 24 (10.13) | 166 (14.91) | 75 (32.05) | 98 (22.74) | |

| Education level | <0.001 | ||||||

| High school or below | 16,257 (28.96) | 16,059 (29.67) | 0 (0.00) | 100 (8.98) | 60 (25.64) | 38 (8.82) | |

| College | 21,247 (37.85) | 19,700 (36.40) | 76 (32.07) | 950 (85.35) | 155 (66.24) | 366 (84.92) | |

| Graduate school or higher | 2522 (4.49) | 2252 (4.16) | 161 (67.93) | 63 (5.66) | 19 (8.12) | 27 (6.26) | |

| Work schedule | <0.001 | ||||||

| Three-shifts | 4921 (8.77) | 4296 (7.94) | 1 (0.42) | 584 (52.47) | 8 (3.42) | 32 (7.42) | |

| Two-shifts | 6912 (12.31) | 6848 (12.65) | 3 (1.27) | 27 (2.43) | 1 (0.43) | 33 (7.66) | |

| Every-other-day shift | 52 (0.09) | 17 (0.03) | 2 (0.84) | 2 (0.18) | 1 (0.43) | 30 (6.96) | |

| Fixed night shift | 57 (0.10) | 32 (0.06) | 8 (3.38) | 5 (0.45) | 0 (0.00) | 12 (2.78) | |

| Other | 752 (1.34) | 540 (1.00) | 77 (32.49) | 64 (5.75) | 2 (0.85) | 69 (16.01) | |

| Marital status | <0.001 | ||||||

| Never married | 9782 (17.43) | 8787 (16.24) | 49 (20.68) | 663 (59.57) | 93 (39.74) | 190 (44.08) | |

| Married | 28,739 (51.19) | 27,757 (51.29) | 185 (78.06) | 428 (38.45) | 138 (58.97) | 231 (53.60) | |

| Separated | 105 (0.19) | 103 (0.19) | 0 (0.00) | 1 (0.09) | 0 (0.00) | 1 (0.23) | |

| Divorced | 997 (1.78) | 970 (1.79) | 2 (0.84) | 16 (1.44) | 2 (0.85) | 7 (1.62) | |

| Widowed | 575 (1.02) | 566 (1.05) | 1 (0.42) | 5 (0.45) | 1 (0.43) | 2 (0.46) | |

| Mental health diagnosis | <0.001 | ||||||

| Yes | 2541 (4.53) | 2519 (4.65) | 6 (2.53) | 7 (0.63) | 5 (2.14) | 4 (0.93) | |

| No | 53,596 (95.47) | 51,603 (95.35) | 231 (97.47) | 1106 (99.37) | 229 (97.86) | 427 (99.07) | |

| Stress score, mean ± SD | 15.25 ± 6.50 | 15.23 ± 6.51 | 15.03 ± 5.86 | 15.95 ± 6.36 | 16.26 ± 6.48 | 14.90 ± 5.73 | <0.001 |

| Anxiety score, mean ± SD | 12.37 ± 12.39 | 12.38 ± 12.42 | 10.89 ± 10.76 | 12.22 ± 11.64 | 14.34 ± 12.51 | 10.73 ± 11.00 | 0.002 |

| 0–25 | 47,213 (84.10) | 45,478 (84.03) | 220 (92.83) | 949 (85.27) | 186 (79.49) | 380 (88.17) | 0.001 |

| 26–50 | 8483 (15.11) | 8217 (15.18) | 15 (6.33) | 154 (13.84) | 47 (20.09) | 50 (11.60) | |

| 51–80 | 441 (0.79) | 427 (0.79) | 2 (0.84) | 10 (0.90) | 1 (0.43) | 1 (0.23) | |

| Depression score, mean ± SD | 8.37 ± 6.75 | 8.37 ± 6.77 | 5.11 ± 7.18 | 9.37 ± 5.77 | 7.72 ± 6.07 | 7.84 ± 5.72 | <0.001 |

| <16 | 50,121 (89.28) | 48,278 (89.20) | 222 (93.67) | 1009 (90.66) | 209 (89.32) | 403 (93.50) | 0.004 |

| ≥16 | 6016 (10.72) | 5844 (10.80) | 15 (6.33) | 104 (9.34) | 25 (10.68) | 28 (6.50) |

| Pre-COVID (Reference) | COVID β (95% CI) | p-Value | Post-COVID β (95% CI) | p-Value | Medical–Government Conflict β (95% CI) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stress | |||||||

| Non-healthcare worker | reference | 0.03 (−0.03, 0.09) | 0.382 | 0.26 (0.19, 0.33) | <0.001 | 0.20 (0.13, 0.26) | <0.001 |

| Physician | reference | 0.62 (−0.07, 1.30) | 0.076 | 1.44 (0.64, 2.23) | <0.001 | 1.17 (0.34, 2.01) | 0.006 |

| Nurse | reference | −0.52 (−1.07, 0.04) | 0.068 | −0.30 (−0.91, 0.30) | 0.331 | −0.91 (−1.49, −0.33) | 0.002 |

| Office worker | reference | 0.42 (−0.44, 1.27) | 0.342 | 0.82 (−0.14, 1.78) | 0.094 | −0.16 (−1.10, 0.77) | 0.737 |

| Others | reference | −0.56 (−1.13, 0.02) | 0.057 | −0.71 (−1.36, −0.06) | 0.031 | −1.09 (−1.72, −0.46) | 0.001 |

| Anxiety | |||||||

| Non-healthcare worker | reference | −0.58 (−0.68, −0.48) | <0.001 | −0.26 (−0.37, −0.14) | <0.001 | −0.28 (−0.40, −0.17) | <0.001 |

| Physician | reference | 0.68 (−0.09, 1.44) | 0.084 | 1.25 (0.28, 2.22) | 0.012 | 1.36 (0.28, 2.43) | 0.013 |

| Nurse | reference | −0.10 (−0.82, 0.61) | 0.774 | −0.19 (−1.01, 0.63) | 0.649 | −0.564 (−1.36, 0.28) | 0.197 |

| Office worker | reference | 0.28 (−0.85, 1.40) | 0.629 | 1.00 (−0.35, 2.36) | 0.147 | 1.15 (−0.24, 2.54) | 0.104 |

| Others | reference | −0.76 (−1.51, −0.01) | 0.047 | −1.26 (−2.17, −0.35) | 0.006 | −0.94 (−1.88, −0.004) | 0.049 |

| Depression | |||||||

| Non-healthcare worker | reference | 0.79 (0.72, 0.86) | <0.001 | 0.91 (0.82, 0.99) | <0.001 | 0.87 (0.79, 0.95) | <0.001 |

| Physician | reference | 0.11 (−0.44, 0.66) | 0.705 | 0.50 (−0.19, 1.19) | 0.152 | 0.43 (−0.33, 1.18) | 0.269 |

| Nurse | reference | 0.15 (−0.45, 0.74) | 0.626 | 0.48 (−0.16, 1.12) | 0.142 | 0.20 (−0.41, 0.81) | 0.515 |

| Office worker | reference | 0.83 (−0.18, 1.84) | 0.107 | 1.66 (0.56, 2.77) | 0.003 | 1.74 (0.67, 2.81) | 0.001 |

| Others | reference | −0.03 (−0.52, 0.50) | 0.916 | 0.31 (−0.26, 0.89) | 0.288 | 0.55 (−0.02, 1.13) | 0.061 |

| Pre-COVID (Reference) | COVID β (95% CI) | p-Value | Post-COVID β (95% CI) | p-Value | Medical–Government Conflict β (95% CI) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stress | |||||||

| <5 yr | reference | 1.36 (−0.48, 3.19) | 0.147 | 3.25 (1.19, 5.31) | 0.002 | 2.62 (0.46, 4.78) | 0.018 |

| 5–14 yr | reference | 1.03 (0.12, 1.95) | 0.027 | 1.41 (0.31, 2.51) | 0.012 | 1.49 (0.33, 2.64) | 0.012 |

| ≧15 yr | reference | 1.08 (−0.45, 2.62) | 0.167 | 2.12 (−0.07, 4.31) | 0.058 | 2.41 (−0.15, 4.97) | 0.065 |

| Anxiety | |||||||

| <5 yr | reference | 3.08 (0.80, 5.36) | 0.008 | 4.35 (1.72, 6.97) | 0.001 | 4.03 (1.21, 6.84) | 0.005 |

| 5–14 yr | reference | 0.50 (−0.64, 1.64) | 0.387 | 0.72 (−0.81, 2.26) | 0.35 | 1.22 (−0.50, 2.94) | 0.165 |

| ≧15 yr | reference | 0.76 (−0.81, 2.32) | 0.343 | 1.48 (−1.33, 4.29) | 0.301 | 1.86 (−1.58, 5.30) | 0.290 |

| Depression | |||||||

| <5 yr | reference | −0.53 (−2.35, 1.28) | 0.563 | 1.03 (−1.02, 3.08) | 0.325 | 0.72 (−1.45, 2.89) | 0.517 |

| 5–14 yr | reference | 0.56 (−0.17, 1.28) | 0.131 | 0.18 (−0.78, 1.14) | 0.709 | 0.35 (−0.72, 1.41) | 0.524 |

| ≧15 yr | reference | 0.56 (−0.66, 1.78) | 0.366 | 1.03 (−1.20, 3.26) | 0.367 | 1.06 (−1.68, 3.80) | 0.449 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kyung, Y. Impact of a Medical–Government Conflict on Healthcare Workers’ Mental Health in a Single Tertiary Hospital. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 8580. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238580

Kyung Y. Impact of a Medical–Government Conflict on Healthcare Workers’ Mental Health in a Single Tertiary Hospital. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(23):8580. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238580

Chicago/Turabian StyleKyung, Yechan. 2025. "Impact of a Medical–Government Conflict on Healthcare Workers’ Mental Health in a Single Tertiary Hospital" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 23: 8580. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238580

APA StyleKyung, Y. (2025). Impact of a Medical–Government Conflict on Healthcare Workers’ Mental Health in a Single Tertiary Hospital. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(23), 8580. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238580