Can BKPyV Infection Affect Neoplasm Transformation Among Kidney Transplant Recipients? A Case Series Study Report

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

3. Case Presentation

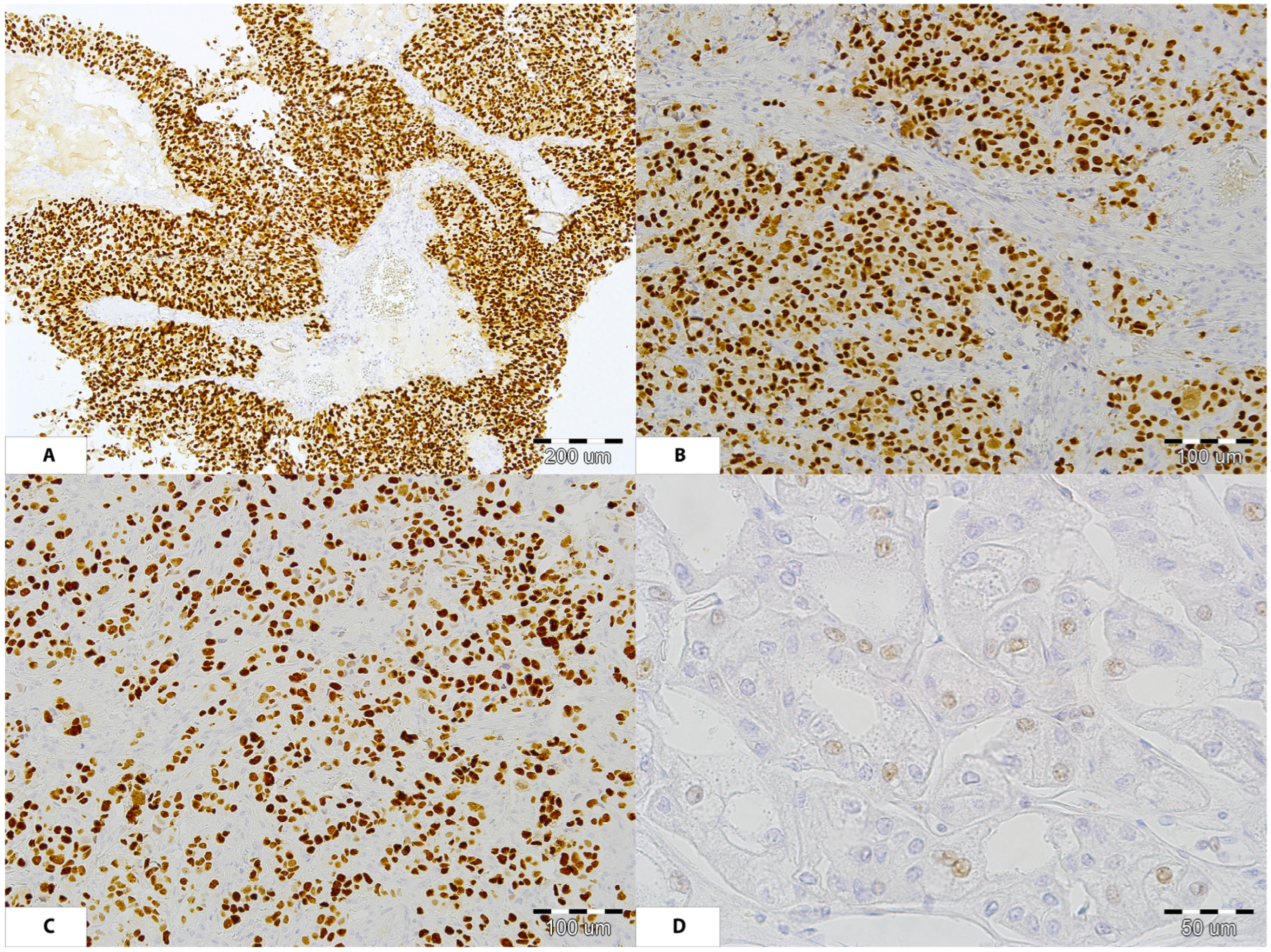

3.1. Patient Number 1

3.2. Patient Number 2

3.3. Patient Number 3

4. Discussion

5. Limitations

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gardner, S.D.; Field, A.M.; Coleman, D.V.; Hulme, B. New Human Papovavirus (B.K.) Isolated from Urine After Renal Transplantation. Lancet 1971, 297, 1253–1257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cook, L. Polyomaviruses. Microbiol. Spectr. 2016, 4, 197–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirsch, H.H.; Randhawa, P. BK Virus in Solid Organ Transplant Recipients. Am. J. Transplant. 2009, 9, S136–S146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirsch, H.H.; Knowles, W.; Dickenmann, M.; Passweg, J.; Klimkait, T.; Mihatsch, M.J.; Steiger, J. Prospective Study of Polyomavirus Type BK Replication and Nephropathy in Renal-Transplant Recipients. N. Engl. J. Med. 2002, 347, 488–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robaina, T.F.; Mendes, G.S.; Benati, F.J.; Pena, G.A.; Silva, R.C.; Montes, M.A.R.; Janini, M.E.R.; Câmara, F.P.; Santos, N. Shedding of Polyomavirus in the Saliva of Immunocompetent Individuals. J. Med. Virol. 2013, 85, 144–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boldorini, R.; Allegrini, S.; Miglio, U.; Nestasio, I.; Paganotti, A.; Veggiani, C.; Monga, G.; Pietropaolo, V. BK Virus Sequences in Specimens from Aborted Fetuses. J. Med. Virol. 2010, 82, 2127–2132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolei, A.; Pietropaolo, V.; Gomes, E.; Di Taranto, C.; Ziccheddu, M.; Spanu, M.A.; Lavorino, C.; Manca, M.; Degener, A.M. Polyomavirus Persistence in Lymphocytes: Prevalence in Lymphocytes from Blood Donors and Healthy Personnel of a Blood Transfusion Centre. J. Gen. Virol. 2000, 81, 1967–1973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohl, D.L.; Brennan, D.C. BK Virus Nephropathy and Kidney Transplantation. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2007, 2, S36–S46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casini, B.; Borgese, L.; Del Nonno, F.; Galati, G.; Izzo, L.; Caputo, M.; Perrone Donnorso, R.; Castelli, M.; Risuleo, G.; Visca, P. Presence and Incidence of DNA Sequences of Human Polyomaviruses BKV and JCV in Colorectal Tumor Tissues. Anticancer Res. 2005, 25, 1079–1085. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Cortese, I.; Reich, D.S.; Nath, A. Progressive Multifocal Leukoencephalopathy and the Spectrum of JC Virus-Related Disease. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 2021, 17, 37–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weinreb, D.B.; Desman, G.T.; Amolat-Apiado, M.J.M.; Burstein, D.E.; Godbold, J.H.; Johnson, E.M. Polyoma Virus Infection Is a Prominent Risk Factor for Bladder Carcinoma in Immunocompetent Individuals. Diagn. Cytopathol. 2006, 34, 201–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tavassoli, N.; Vojdani, A.; Salimi-Namin, S.; Khadem-Rezaiyan, M.; Kalantari, M.; Youssefi, M. Human BKV Large T Genome Detection in Prostate Cancer and Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia Tissue Samples by Nested PCR: A Case-Control Study. Mol. Biol. Res. Commun. 2023, 12, 149–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massicotte-Azarniouch, D.; Noel, J.A.; Knoll, G.A. Epidemiology of Cancer in Kidney Transplant Recipients. Semin. Nephrol. 2024, 44, 151494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, I.S.D.; Besarani, D.; Mason, P.; Turner, G.; Friend, P.J.; Newton, R. Polyoma Virus Infection and Urothelial Carcinoma of the Bladder Following Renal Transplantation. Br. J. Cancer 2008, 99, 1383–1386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abend, J.R.; Jiang, M.; Imperiale, M.J. BK Virus and Human Cancer: Innocent until Proven Guilty. Semin. Cancer Biol. 2009, 19, 252–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boratyńska, M.; Rybka, K. Malignant Melanoma in a Patient with Polyomavirus-BK-Associated Nephropathy. Transpl. Infect. Dis. 2005, 7, 150–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galed-Placed, I.; Valbuena-Ruvira, L. Decoy Cells and Malignant Cells Coexisting in the Urine from a Transplant Recipient with BK Virus Nephropathy and Bladder Adenocarcinoma. Diagn. Cytopathol. 2011, 39, 933–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamminga, S.; Meijden, E.; Brouwer, C.; Feltkamp, M.; Zaaijer, H. Prevalence of DNA of Fourteen Human Polyomaviruses Determined in Blood Donors. Transfusion 2019, 59, 3689–3697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamminga, S.; van der Meijden, E.; Feltkamp, M.C.W.; Zaaijer, H.L. Seroprevalence of Fourteen Human Polyomaviruses Determined in Blood Donors. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0206273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alvarez Orellana, J.; Kwun, H.J.; Artusi, S.; Chang, Y.; Moore, P.S. Sirolimus and Other Mechanistic Target of Rapamycin Inhibitors Directly Activate Latent Pathogenic Human Polyomavirus Replication. J. Infect. Dis. 2020, 224, 1160–1169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cho, A.; Park, S.; Han, A.; Ha, J.; Park, J.B.; Lee, K.W.; Min, S. A Comparative Analysis of Clinical Outcomes between Conversion to MTOR Inhibitor and Calcineurin Inhibitor Reduction in Managing BK Viremia among Kidney Transplant Patients. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 12855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bussalino, E.; Marsano, L.; Parodi, A.; Russo, R.; Massarino, F.; Ravera, M.; Gaggero, G.; Fontana, I.; Garibotto, G.; Zaza, G.; et al. Everolimus for BKV Nephropathy in Kidney Transplant Recipients: A Prospective, Controlled Study. J. Nephrol. 2021, 34, 531–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kotton, C.N.; Kamar, N.; Wojciechowski, D.; Eder, M.; Hopfer, H.; Randhawa, P.; Sester, M.; Comoli, P.; Tedesco Silva, H.; Knoll, G.; et al. The Second International Consensus Guidelines on the Management of BK Polyomavirus in Kidney Transplantation. Transplantation 2024, 108, 1834–1866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kasiske, B.L.; Snyder, J.J.; Gilbertson, D.T.; Wang, C. Cancer after Kidney Transplantation in the United States. Am. J. Transplant. 2004, 4, 905–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vajdic, C.M.; McDonald, S.P.; McCredie, M.R.E.; Van Leeuwen, M.T.; Stewart, J.H.; Law, M.; Chapman, J.R.; Webster, A.C.; Kaldor, J.M.; Grulich, A.E. Cancer Incidence before and after Kidney Transplantation. J. Am. Med. Assoc. 2006, 296, 2823–2831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenan, D.J.; Mieczkowski, P.A.; Latulippe, E.; Côté, I.; Singh, H.K.; Nickeleit, V. BK Polyomavirus Genomic Integration and Large T Antigen Expression: Evolving Paradigms in Human Oncogenesis. Am. J. Transplant. 2017, 17, 1674–1680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenan, D.J.; Mieczkowski, P.A.; Burger-Calderon, R.; Singh, H.K.; Nickeleit, V. The Oncogenic Potential of BK-polyomavirus Is Linked to Viral Integration into the Human Genome. J. Pathol. 2015, 237, 379–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biffi, R.; Benoit, S.W.; Sariyer, I.K.; Safak, M. JC Virus Small Tumor Antigen Promotes S Phase Entry and Cell Cycle Progression. Tumour Virus Res. 2024, 18, 200298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalianis, T.; Hirsch, H.H. Human Polyomaviruses in Disease and Cancer. Virology 2013, 437, 63–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramqvist, T.; Dalianis, T. Murine Polyomavirus Tumour Specific Transplantation Antigens and Viral Persistence in Relation to the Immune Response, and Tumour Development. Semin. Cancer Biol. 2009, 19, 236–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prado, J.C.M.; Monezi, T.A.; Amorim, A.T.; Lino, V.; Paladino, A.; Boccardo, E. Human Polyomaviruses and Cancer: An Overview. Clinics 2018, 73, e558s. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emerson, L.L.; Carney, H.M.; Layfield, L.J.; Sherbotie, J.R. Collecting Duct Carcinoma Arising in Association with Bk Nephropathy Post-Transplantation in a Pediatric Patient. a Case Report with Immunohistochemical and in Situ Hybridization Study. Pediatr. Transpl. 2008, 12, 600–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neirynck, V.; Claes, K.; Naesens, M.; De Wever, L.; Pirenne, J.; Kuypers, D.; Vanrenterghem, Y.; Van Poppel, H.; Kabanda, A.; Lerut, E. Renal Cell Carcinoma in the Allograft: What Is the Role of Polyomavirus. Case Rep. Nephrol. Urol. 2012, 2, 125–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulut, Y.; Ozdemir, E.; Ozercan, H.I.; Etem, E.O.; Aker, F.; Toraman, Z.A.; Seyrek, A.; Firdolas, F. Potential Relationship between BK Virus and Renal Cell Carcinoma. J. Med. Virol. 2013, 85, 1085–1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hall, E.C.; Pfeiffer, R.M.; Segev, D.L.; Engels, E.A. Cumulative Incidence of Cancer after Solid Organ Transplantation. Cancer 2013, 119, 2300–2308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Contractor, H.; Zariwala, M.; Bugert, P.; Zeisler, J.; Kovacs, G. Mutation of the P53 Tumour Suppressor Gene Occurs Preferentially in the Chromophobe Type of Renal Cell Tumour. J. Pathol. 1997, 181, 136–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shoraka, H.R.; Abobakri, O.; Naghibzade Tahami, A.; Mollaei, H.R.; Bagherinajad, Z.; Malekpour Afshar, R.; Shahesmaeili, A. Prevalence of JC and BK Viruses in Patients with Colorectal Cancer: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. 2020, 21, 1499–1509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soltani, S.; Farahani, A.; Shahbahrami, R.; Shateri, Z.; Emadi, M.S.; Pakzad, R.; Lotfi, M.; Asanjarani, B.; Rasti, A.; Erfani, Y.; et al. Investigation of Epstein–Barr Virus, Cytomegalovirus, Human Herpesvirus 6, and Polyoma Viruses (JC Virus, BK Virus) among Gastric Cancer Patients: A Cross Sectional Study. Health Sci. Rep. 2024, 7, e2043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saadh, M.J.; Mustafa, A.N.; Taher, S.G.; Adil, M.; Athab, Z.H.; Baymakov, S.; Alsaikhan, F.; Bagheri, H. Association of Polyomavirus Infection with Lung Cancer: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Pathol. Res. Pr. 2024, 262, 155521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mousavi, T.; Shokoohy, F.; Moosazadeh, M. Polyomaviruses and the Risk of Breast Cancer: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Infect. Agents Cancer 2025, 20, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mousavi, T.; Shokoohy, F.; Moosazadeh, M. Polyomaviruses and the Risk of Oral Cancer: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. BMC Oral Health 2024, 24, 1490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Patient No. 1 | Patient No. 2 | Patient No. 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cause of end-stage kidney disease | Membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis | Chronic glomerulonephritis | Distal tubular acidosis with nephrocalcinosis |

| Year of Tx | 2003 | 2004 | 2002 |

| Previous Tx | No | No | No |

| Recipient’s gender | Male | Male | Male |

| Donor’s gender | Male | Female | Female |

| Recipient’s age at Tx [y] | 45 | 52 | 44 |

| Donor’s age at Tx [y] | 62 | 46 | 28 |

| Cold ischemia time | 23 h | 35 h | 15 h |

| No of episodes of AR previous to NPL | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Time from Tx to AR [m] | 3 | 5 | - |

| IS protocol | CsA, AZA, GCs | TAC, MMF, GCs | Sirolimus, CsA, GCs |

| Time from Tx to NPL [y] | 7 | 10 | 6 |

| Age at the time of NPL | 52 | 62 | 50 |

| NPL type | Native kidney’s chromophobe cancer | Colorectal cancer | Urothelial cancer |

| IS conversion | CsA, MMF, GCs | Everolimus, CsA, GCs | CsA, MMF, GCs |

| Treatment of NPL | Surgery (nephrectomy) | Surgery (resection) | TURB, intravesical Bacillus Calmette–Guérin therapy |

| Return to dialysis | + | - | No data |

| Results | cured | cured | death during treatment |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Poznański, P.; Wenta, M.; Augustyniak-Bartosik, H.; Rukasz, D.; Hałoń, A.; Kościelska-Kasprzak, K.; Kamińska, D.; Krajewska, M. Can BKPyV Infection Affect Neoplasm Transformation Among Kidney Transplant Recipients? A Case Series Study Report. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 8550. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238550

Poznański P, Wenta M, Augustyniak-Bartosik H, Rukasz D, Hałoń A, Kościelska-Kasprzak K, Kamińska D, Krajewska M. Can BKPyV Infection Affect Neoplasm Transformation Among Kidney Transplant Recipients? A Case Series Study Report. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(23):8550. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238550

Chicago/Turabian StylePoznański, Paweł, Maciej Wenta, Hanna Augustyniak-Bartosik, Dagna Rukasz, Agnieszka Hałoń, Katarzyna Kościelska-Kasprzak, Dorota Kamińska, and Magdalena Krajewska. 2025. "Can BKPyV Infection Affect Neoplasm Transformation Among Kidney Transplant Recipients? A Case Series Study Report" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 23: 8550. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238550

APA StylePoznański, P., Wenta, M., Augustyniak-Bartosik, H., Rukasz, D., Hałoń, A., Kościelska-Kasprzak, K., Kamińska, D., & Krajewska, M. (2025). Can BKPyV Infection Affect Neoplasm Transformation Among Kidney Transplant Recipients? A Case Series Study Report. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(23), 8550. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238550