Spectrum of Cervical Insufficiency: Management Strategies from Asymptomatic Shortening to Emergent Membrane Prolapse

Abstract

1. Introduction

Epidemiology and Population Demographics

2. Methods

2.1. Literature Search Strategy

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

2.3. Quality Assessment and Evidence Synthesis

2.4. Classification

3. Pathophysiology and Risk Factors

3.1. Molecular Mechanisms and Cervical Remodeling

3.2. Risk Factors and Clinical Associations

3.2.1. Congenital Risk Factors

3.2.2. Acquired Risk Factors

4. Contemporary Diagnostic Framework

4.1. Evidence-Based Classification System

4.2. Ultrasonographic Assessment Standards

Technical Standardization

5. Management of Asymptomatic Short Cervix

5.1. Vaginal Progesterone Therapy

Mechanisms of Progesterone Action

6. High-Risk Population Management

6.1. Ultrasound-Indicated Cerclage

6.2. History-Indicated Cerclage

6.3. Combination Therapy

7. Comparative Effectiveness Evidence

7.1. The SuPPoRT Trial

7.2. Cervical Pessary Evidence

8. Emergency and Advanced Presentations

Emergency Cerclage

9. Multiple Gestations

Distinct Pathophysiology

10. Implementation and Future Directions

10.1. Universal Cervical Length Screening

10.2. Biomarker Development

10.3. Novel Therapeutic Approaches

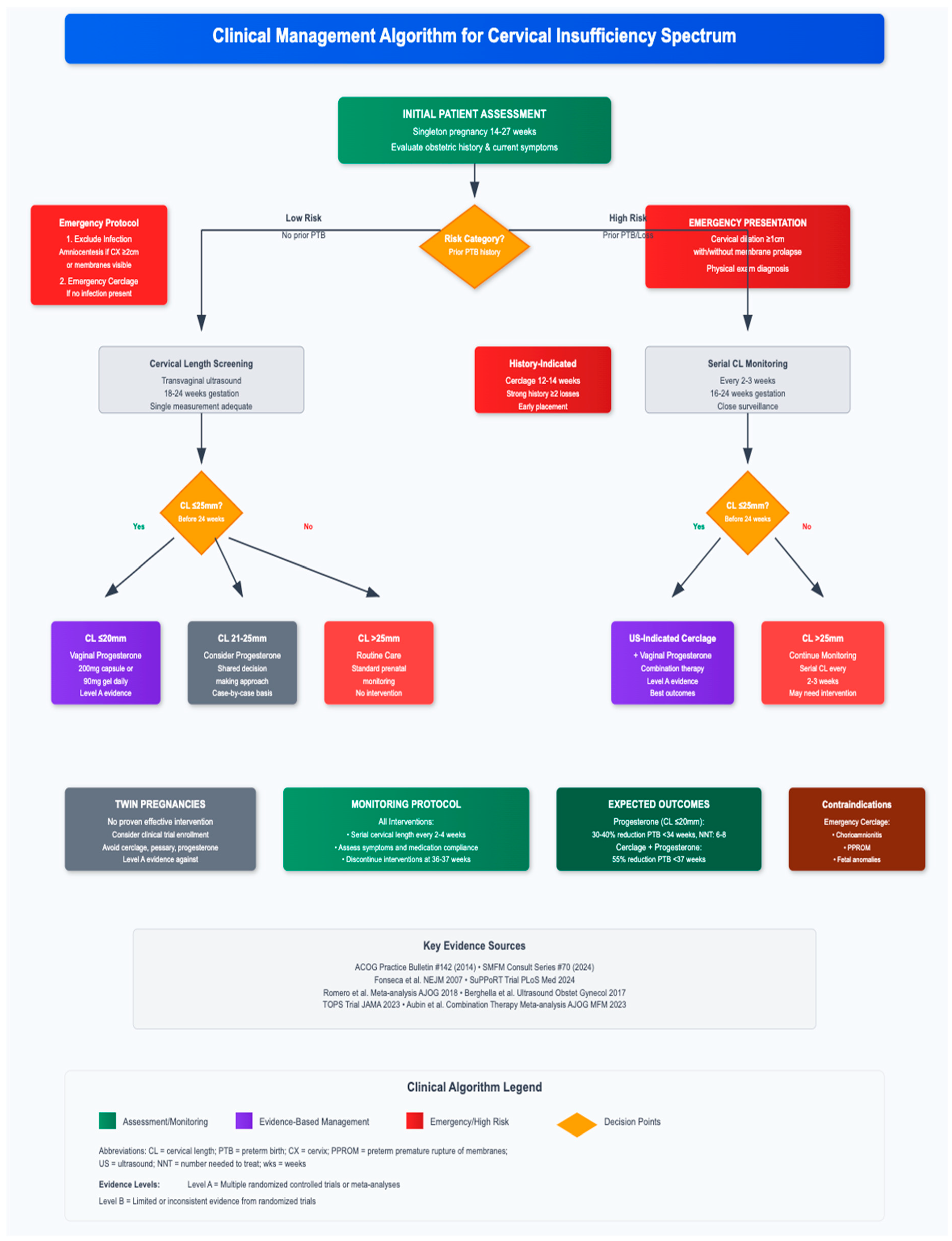

11. Clinical Algorithm and Decision-Making

12. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 142: Cerclage for the management of cervical insufficiency. Obstet. Gynecol. 2014, 123, 372–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iams, J.D.; Berghella, V. Care for women with prior preterm birth. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2010, 203, 89–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iams, J.D.; Goldenberg, R.L.; Mercer, B.M.; Moawad, A.; Meis, P.J.; Das, A.; Thom, E.; McNellis, D.; Copper, R.L.; Johnson, F.; et al. The Preterm Prediction Study: Recurrence risk of spontaneous preterm birth. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 1998, 178, 1035–1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mercer, B.M.; Goldenberg, R.L.; Moawad, A.H.; Meis, P.J.; Iams, J.D.; Das, A.F.; Caritis, S.N.; Miodovnik, M.; Menard, M.K.; Thurnau, G.R.; et al. The preterm prediction study: Effect of gestational age and cause of preterm birth on subsequent obstetric outcome. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 1999, 181, 1216–1221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonald, I.A. Suture of the cervix for inevitable miscarriage. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. Br. Emp. 1957, 64, 346–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Story, L.; Shennan, A. Cervical cerclage: An evolving evidence base. BJOG 2024, 131, 1579–1586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vink, J.; Feltovich, H. Cervical etiology of spontaneous preterm birth. Semin. Fetal Neonatal Med. 2016, 21, 106–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Hara, S.; Zelesco, M.; Sun, Z. Cervical length for predicting preterm birth and a comparison of ultrasonic measurement techniques. Australas. J. Ultrasound Med. 2013, 16, 124–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owen, J.; Yost, N.; Berghella, V.; Thom, E.; Swain, M.; Dildy, G.A.; Miodovnik, M.; Langer, O.; Sibai, B.; McNellis, D. Mid-trimester endovaginal sonography in women at high risk for spontaneous preterm birth. JAMA 2001, 286, 1340–1348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iams, J.D.; Goldenberg, R.L.; Meis, P.J.; Mercer, B.M.; Moawad, A.; Das, A.; Thom, E.; McNellis, D.; Copper, R.L.; Johnson, F.; et al. The length of the cervix and the risk of spontaneous premature delivery. N. Engl. J. Med. 1996, 334, 567–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Understanding Premature Birth and Assuring Healthy Outcomes. Preterm Birth: Causes, Consequences, and Prevention; Behrman, R.E., Butler, A.S., Eds.; National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrou, S.; Mehta, Z.; Hockley, C.; Cook-Mozaffari, P.; Henderson, J.; Goldacre, M. The impact of preterm birth on hospital inpatient admissions and costs during the first 5 years of life. Pediatrics 2003, 112, 1290–1297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Werner, E.F.; Hamel, M.S.; Orzechowski, K.; Berghella, V.; Thung, S.F. Cost-effectiveness of transvaginal ultrasound cervical length screening in singletons without a prior preterm birth: An update. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2015, 213, 554.e1–554.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goldenberg, R.L.; Culhane, J.F.; Iams, J.D.; Romero, R. Epidemiology and causes of preterm birth. Lancet 2008, 371, 75–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adams, M.M.; Elam-Evans, L.D.; Wilson, H.G.; Gilbertz, D.A. Rates of and factors associated with recurrence of preterm delivery. JAMA 2000, 283, 1591–1596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kristensen, J.; Langhoff-Roos, J.; Kristensen, F.B. Implications of idiopathic preterm delivery for previous and subsequent pregnancies. Obstet. Gynecol. 1995, 86, 800–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitrogiannis, I.; Evangelou, E.; Efthymiou, A.; Kanavos, T.; Birbas, E.; Makrydimas, G.; Papatheodorou, S. Risk factors for preterm labor: An Umbrella Review of meta-analyses of observational studies. BMC Med. 2023, 21, 494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kramer, M.R.; Hogue, C.R. What causes racial disparities in very preterm birth? A biosocial perspective. Epidemiol. Rev. 2009, 31, 84–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Culhane, J.F.; Goldenberg, R.L. Racial disparities in preterm birth. Semin. Perinatol. 2011, 35, 234–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, M.C.; Halfon, N. Racial and ethnic disparities in birth outcomes: A life-course perspective. Matern. Child. Health J. 2003, 7, 13–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiscella, K. Race, perinatal outcome, and amniotic infection. Obstet. Gynecol. Surv. 1996, 51, 60–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cleary-Goldman, J.; Malone, F.D.; Vidaver, J.; Ball, R.H.; Nyberg, D.A.; Comstock, C.H.; Saade, G.R.; Eddleman, K.A.; Klugman, S.; Dugoff, L.; et al. Impact of maternal age on obstetric outcome. Obstet. Gynecol. 2005, 105, 983–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luke, B.; Brown, M.B. Elevated risks of pregnancy complications and adverse outcomes with increasing maternal age. Hum. Reprod. 2007, 22, 1264–1272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Practice Committee of the American Society for Reproductive Medicine. Smoking and infertility: A committee opinion. Fertil. Steril. 2018, 110, 611–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Myers, K.M.; Feltovich, H.; Mazza, E.; Vink, J.; Bajka, M.; Wapner, R.J.; Hall, T.J.; House, M. The mechanical role of the cervix in pregnancy. J. Biomech. 2015, 48, 1511–1523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- House, M.; Kaplan, D.L.; Socrate, S. Relationships between mechanical properties and extracellular matrix constituents of the cervical stroma during pregnancy. Semin. Perinatol. 2009, 33, 300–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leppert, P.C. Anatomy and physiology of cervical ripening. Clin. Obstet. Gynecol. 1995, 38, 267–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshida, K.; Jiang, H.; Kim, M.; Vink, J.; Cremers, S.; Paik, D.; Wapner, R.; Mahendroo, M.; Myers, K. Quantitative evaluation of collagen crosslinks and corresponding tensile mechanical properties in mouse cervical tissue during normal pregnancy. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e112391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winkler, M.; Rath, W. Changes in the cervical extracellular matrix during pregnancy and parturition. J. Perinat. Med. 1999, 27, 45–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Read, C.P.; Word, R.A.; Ruscheinsky, M.A.; Timmons, B.C.; Mahendroo, M.S. Cervical remodeling during pregnancy and parturition: Molecular characterization of the softening phase in mice. Reproduction 2007, 134, 327–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Straach, K.J.; Shelton, J.M.; Richardson, J.A.; Hascall, V.C.; Mahendroo, M.S. Regulation of hyaluronan expression during cervical ripening. Glycobiology 2005, 15, 55–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, S.S.; Romero, R.; Tarca, A.L.; Nhan-Chang, C.L.; Vaisbuch, E.; Erez, O.; Mittal, P.; Kusanovic, J.P.; Mazaki-Tovi, S.; Yeo, L.; et al. Signature pathways identified from gene expression profiles in the human uterine cervix before and after spontaneous term parturition. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2007, 197, 250.e1–250.e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Word, R.A.; Li, X.H.; Hnat, M.; Carrick, K. Dynamics of cervical remodeling during pregnancy and parturition: Mechanisms and current concepts. Semin. Reprod. Med. 2007, 25, 69–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Timmons, B.; Akins, M.; Mahendroo, M. Cervical remodeling during pregnancy and parturition. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 2010, 21, 353–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Warren, J.E.; Silver, R.M.; Dalton, J.; Nelson, L.T.; Branch, D.W.; Porter, T.F. Collagen 1Alpha1 and transforming growth factor-beta polymorphisms in women with cervical insufficiency. Obstet. Gynecol. 2007, 110, 619–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anum, E.A.; Hill, L.D.; Pandya, A.; Strauss, J.F., 3rd. Connective tissue and related disorders and preterm birth: Clues to genes contributing to prematurity. Placenta 2009, 30, 207–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yellon, S.M. Immunobiology of cervix ripening. Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 3156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osman, I.; Young, A.; Ledingham, M.A.; Thomson, A.J.; Jordan, F.; Greer, I.A.; Norman, J.E. Leukocyte density and pro-inflammatory cytokine expression in human fetal membranes, decidua, cervix and myometrium before and during labour at term. Mol. Hum. Reprod. 2003, 9, 41–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ludmir, J.; Sehdev, H.M. Anatomy and physiology of the uterine cervix. Clin. Obstet. Gynecol. 2000, 43, 433–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lidegaard, O. Cervical incompetence and cerclage in Denmark 1980–1990. A register based epidemiological survey. Acta Obstet. Gynecol. Scand. 1994, 73, 35–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acién, P. Incidence of Müllerian defects in fertile and infertile women. Hum. Reprod. 1997, 12, 1372–1376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaufman, R.H.; Adam, E.; Hatch, E.E.; Noller, K.; Herbst, A.L.; Palmer, J.R.; Hoover, R.N. Continued follow-up of pregnancy outcomes in diethylstilbestrol-exposed offspring. Obstet. Gynecol. 2000, 96, 483–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lind, J.; Wallenburg, H.C. Pregnancy and the Ehlers-Danlos syndrome: A retrospective study in a Dutch population. Acta Obstet. Gynecol. Scand. 2002, 81, 293–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rahman, J.; Rahman, F.Z.; Rahman, W.; al-Suleiman, S.A.; Rahman, M.S. Obstetric and gynecologic complications in women with Marfan syndrome. J. Reprod. Med. 2003, 48, 723–728. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Meng, L.; Öberg, S.; Sandström, A.; Wang, C.; Reilly, M. Identification of risk factors for incident cervical insufficiency in nulliparous and parous women: A population-based case-control study. BMC Med. 2022, 20, 352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorp, J.M., Jr.; Hartmann, K.E.; Shadigian, E. Long-term physical and psychological health consequences of induced abortion: Review of the evidence. Obstet. Gynecol. Surv. 2003, 58, 67–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyrgiou, M.; Koliopoulos, G.; Martin-Hirsch, P.; Arbyn, M.; Prendiville, W.; Paraskevaidis, E. Obstetric outcomes after conservative treatment for intraepithelial or early invasive cervical lesions: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet 2006, 367, 489–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arbyn, M.; Kyrgiou, M.; Simoens, C.; Raifu, A.O.; Koliopoulos, G.; Martin-Hirsch, P.; Prendiville, W.; Paraskevaidis, E. Perinatal mortality and other severe adverse pregnancy outcomes associated with treatment of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia: Meta-analysis. BMJ 2008, 337, a1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noehr, B.; Jensen, A.; Frederiksen, K.; Tabor, A.; Kjaer, S.K. Depth of cervical cone removed by loop electrosurgical excision procedure and subsequent risk of spontaneous preterm delivery. Obstet. Gynecol. 2009, 114, 1232–1238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadler, L.; Saftlas, A.; Wang, W.; Exeter, M.; Whittaker, J.; McCowan, L. Treatment for cervical intraepithelial neoplasia and risk of preterm delivery. JAMA 2004, 291, 2100–2106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conner, S.N.; Frey, H.A.; Cahill, A.G.; Macones, G.A.; Colditz, G.A.; Tuuli, M.G. Loop electrosurgical excision procedure and risk of preterm birth: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Obstet. Gynecol. 2014, 123, 752–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakobsson, M.; Gissler, M.; Paavonen, J.; Tapper, A.M. Loop electrosurgical excision procedure and the risk for preterm birth. Obstet. Gynecol. 2009, 114, 504–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine (SMFM). SMFM Consult Series #70: Management of short cervix in individuals without a history of spontaneous preterm birth. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2024, 231, B2–B18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, R.; Gagnon, R.; Delisle, M.F. No. 373-Cervical Insufficiency and Cervical Cerclage. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. Can. 2019, 41, 233–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berghella, V.; Ciardulli, A.; Rust, O.A.; To, M.; Otsuki, K.; Althuisius, S.; Nicolaides, K.H.; Roman, A.; Saccone, G. Cerclage for sonographic short cervix in singleton gestations without prior spontaneous preterm birth: Systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials using individual patient-level data. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 2017, 50, 569–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Preterm Labour and Birth. NICE Guideline [NG25]. Available online: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng25 (accessed on 1 November 2015).

- Spong, C.Y. Prediction and prevention of recurrent spontaneous preterm birth. Obstet. Gynecol. 2007, 110, 405–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berghella, V.; Roman, A.; Daskalakis, C.; Ness, A.; Baxter, J.K. Gestational age at cervical length measurement and incidence of preterm birth. Obstet. Gynecol. 2007, 110, 311–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crane, J.M.; Hutchens, D. Transvaginal sonographic measurement of cervical length to predict preterm birth in asymptomatic women at increased risk: A systematic review. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 2008, 31, 579–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coutinho, C.M.; Sotiriadis, A.; Odibo, A.; Khalil, A.; D’Antonio, F.; Feltovich, H.; Salomon, L.J.; Sheehan, P.; Napolitano, R.; Berghella, V.; et al. ISUOG Practice Guidelines: Role of ultrasound in the prediction of spontaneous preterm birth. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 2022, 60, 435–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- To, M.S.; Skentou, C.; Cicero, S.; Nicolaides, K.H. Cervical assessment at the routine 23-weeks’ scan: Standardizing techniques. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 2001, 17, 217–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ko, H.S.; Jo, Y.S.; Kil, K.C.; Chang, H.K.; Park, Y.G.; Park, I.Y.; Lee, G.; Kim, S.; Shin, J.C. The Clinical Significance of Digital Examination-Indicated Cerclage in Women with a Dilated Cervix at 14 0/7–29 6/7 Weeks. Int. J. Med. Sci. 2011, 8, 529–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yost, N.P.; Owen, J.; Berghella, V.; MacPherson, C.; Swain, M.; Dildy, G.A., 3rd; Miodovnik, M.; Langer, O.; Sibai, B.; McNellis, D. Second-trimester cervical sonography: Features other than cervical length to predict spontaneous preterm birth. Obstet. Gynecol. 2004, 103, 457–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sonek, J.D.; Iams, J.D.; Blumenfeld, M.; Johnson, F.; Landon, M.; Gabbe, S. Measurement of cervical length in pregnancy: Comparison between vaginal ultrasonography and digital examination. Obstet. Gynecol. 1990, 76, 172–175. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Cook, C.M.; Ellwood, D.A. A longitudinal study of the cervix in pregnancy using transvaginal ultrasound. Br. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 1996, 103, 16–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sotiriadis, A.; Papatheodorou, S.; Kavvadias, A.; Makrydimas, G. Transvaginal cervical length measurement for prediction of preterm birth in women with threatened preterm labor: A meta-analysis. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 2010, 35, 54–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfirevic, Z.; Stampalija, T.; Medley, N. Cervical stitch (cerclage) for preventing preterm birth in singleton pregnancy. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2017, 6, CD008991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berghella, V.; Kuhlman, K.; Weiner, S.; Texeira, L.; Wapner, R.J. Cervical funneling: Sonographic criteria and clinical significance. Obstet. Gynecol. 1997, 90, 707–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guzman, E.R.; Rosenberg, J.C.; Houlihan, C.; Ivan, J.; Waldron, R.; Knuppel, R. A new method using vaginal ultrasound and transfundal pressure to evaluate the asymptomatic incompetent cervix. Obstet. Gynecol. 1994, 83, 248–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kurtzman, J.T.; Jenkins, S.M.; Brewster, W.R. Dynamic cervical change during real-time ultrasound: Prospective characterization and comparison in patients with and without symptoms of preterm labor. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 2004, 23, 574–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heath, V.C.; Southall, T.R.; Souka, A.P.; Elisseou, A.; Nicolaides, K.H. Cervical length at 23 weeks of gestation: Prediction of spontaneous preterm delivery. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 1998, 12, 312–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dodd, J.M.; Flenady, V.J.; Cincotta, R.; Crowther, C.A. Progesterone for the prevention of preterm birth: A systematic review. Obstet. Gynecol. 2008, 112, 127–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norman, J.E.; Shennan, A.; Bennett, P.; Thornton, S. Progesterone for the prevention of preterm birth. BJOG 2018, 125, 1201–1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norman, J.E.; Marlow, N.; Messow, C.M.; Shennan, A.; Bennett, P.R.; Thornton, S.; Robson, S.C.; McConnachie, A.; Petrou, S.; Sebire, N.J.; et al. Vaginal progesterone prophylaxis for preterm birth (the OPPTIMUM study): A multicentre, randomised, double-blind trial. Lancet 2016, 387, 2106–2116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Fonseca, E.B.; Bittar, R.E.; Carvalho, M.H.; Zugaib, M. Prophylactic administration of progesterone by vaginal suppository to reduce the incidence of spontaneous preterm birth in women at increased risk: A randomized placebo-controlled double-blind study. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2003, 188, 419–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonseca, E.B.; Celik, E.; Parra, M.; Singh, M.; Nicolaides, K.H. Progesterone and the risk of preterm birth among women with a short cervix. N. Engl. J. Med. 2007, 357, 462–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, S.S.; Romero, R.; Vidyadhari, D.; Fusey, S.; Baxter, J.K.; Khandelwal, M.; Vijayaraghavan, J.; Trivedi, Y.; Soma-Pillay, P.; Sambarey, P.; et al. Vaginal progesterone reduces the rate of preterm birth in women with a sonographic short cervix: A multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 2011, 38, 18–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero, R.; Conde-Agudelo, A.; Da Fonseca, E.; O’Brien, J.M.; Cetingoz, E.; Creasy, G.W.; Hassan, S.S.; Nicolaides, K.H. Vaginal progesterone for preventing preterm birth and adverse perinatal outcomes in singleton gestations with a short cervix: A meta-analysis of individual patient data. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2018, 218, 161–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mendelson, C.R.; Gao, L.; Montalbano, A.P. Multifactorial Regulation of Myometrial Contractility During Pregnancy and Parturition. Front Endocrinol. 2019, 10, 714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Merlino, A.A.; Welsh, T.N.; Tan, H.; Yi, L.J.; Cannon, V.; Mercer, B.M.; Mesiano, S. Nuclear progesterone receptors in the human pregnancy myometrium: Evidence that parturition involves functional progesterone withdrawal mediated by increased expression of progesterone receptor-A. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2007, 92, 1927–1933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mesiano, S.; Chan, E.C.; Fitter, J.T.; Kwek, K.; Yeo, G.; Smith, R. Progesterone withdrawal and estrogen activation in human parturition are coordinated by progesterone receptor A expression in the myometrium. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2002, 87, 2924–2930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arck, P.C.; Hecher, K. Fetomaternal immune cross-talk and its consequences for maternal and offspring’s health. Nat. Med. 2013, 19, 548–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yellon, S.M.; Burns, A.E.; See, J.L.; Lechuga, T.J.; Kirby, M.A. Progesterone withdrawal promotes remodeling processes in the nonpregnant mouse cervix. Biol. Reprod. 2009, 81, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yellon, S.M.; Dobyns, A.E.; Beck, H.L.; Kurtzman, J.T.; Garfield, R.E.; Kirby, M.A. Loss of progesterone receptor-mediated actions induce preterm cellular and structural remodeling of the cervix and premature birth. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e81340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- To, M.S.; Alfirevic, Z.; Heath, V.C.; Cicero, S.; Cacho, A.M.; Williamson, P.R.; Nicolaides, K.H. Cervical cerclage for prevention of preterm delivery in women with short cervix: Randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2004, 363, 1849–1853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Althuisius, S.M.; Dekker, G.A.; Hummel, P.; van Geijn, H.P. Cervical incompetence prevention randomized cerclage trial: Emergency cerclage with bed rest versus bed rest alone. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2003, 189, 907–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berghella, V.; Rafael, T.J.; Szychowski, J.M.; Rust, O.A.; Owen, J. Cerclage for short cervix on ultrasonography in women with singleton gestations and previous preterm birth: A meta-analysis. Obstet. Gynecol. 2011, 117, 663–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rust, O.A.; Atlas, R.O.; Reed, J.; van Gaalen, J.; Balducci, J. Revisiting the short cervix detected by transvaginal ultrasound in the second trimester: Why cerclage therapy may not help. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2001, 185, 1098–1105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berghella, V.; Mackeen, A.D. Cervical length screening with ultrasound-indicated cerclage compared with history-indicated cerclage for prevention of preterm birth: A meta-analysis. Obstet. Gynecol. 2011, 118, 148–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Y.; Wang, S. Comparison of emergency cervical cerclage and expectant treatment in cervical insufficiency in singleton pregnancy: A meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 2023, 24, e0278342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Final report of the Medical Research Council/Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists multicentre randomised trial of cervical cerclage. Br. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 1993, 100, 516–523. [CrossRef]

- Lazar, P.; Gueguen, S.; Dreyfus, J.; Renaud, R.; Pontonnier, G.; Papiernik, E. Multicentred controlled trial of cervical cerclage in women at moderate risk of preterm delivery. Br. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 1984, 91, 731–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harger, J.H. Comparison of success and morbidity in cervical cerclage procedures. Obstet. Gynecol. 1980, 56, 543–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McDonald, I.A. Cervical cerclage. Clin. Obstet. Gynaecol. 1980, 7, 461–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hidalgo Yánez, R.; Solorzano Alcivar, D.M.; Chavez Iza, S. Perinatal Outcomes Associated with the Modified Shirodkar Cervical Cerclage Technique. Cureus. 2024, 16, e62924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aubin, A.M.; McAuliffe, L.; Williams, K.; Issah, A.; Diacci, R.; McAuliffe, J.E.; Sabdia, S.; Phung, J.; Wang, C.A.; Pennell, C.E. Combined vaginal progesterone and cervical cerclage in the prevention of preterm birth: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. MFM 2023, 5, 101024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tolosa, J.E.; Boelig, R.C.; Bell, J.; Martínez-Baladejo, M.; Stoltzfus, J.; Mateus, J.; Quiñones, J.N.; Galeano-Herrera, S.; Pereira, L.; Burwick, R.; et al. Concurrent progestogen and cerclage to reduce preterm birth: A multicenter international retrospective cohort. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. MFM 2024, 6, 101351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hezelgrave, N.L.; Suff, N.; Seed, P.; Girling, J.; Heenan, E.; Briley, A.L.; Shennan, A.H. Comparing cervical cerclage, pessary and vaginal progesterone for prevention of preterm birth in women with a short cervix (SuPPoRT): A multicentre randomised controlled trial. PLoS Med. 2024, 21, e1004427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamburg, M.A.; Collins, F.S. The path to personalized medicine. N. Engl. J. Med. 2010, 363, 301–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, L.; Gao, Y.; Yuan, C.; Kuang, H. Effects of vaginal progesterone and placebo on preterm birth and antenatal outcomes in women with singleton pregnancies and short cervix on ultrasound: A meta-analysis. Front. Med. 2024, 11, 1328014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdel-Aleem, H.; Shaaban, O.M.; Abdel-Aleem, M.A. Cervical pessary for preventing preterm birth. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2013, 5, CD007873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goya, M.; Pratcorona, L.; Merced, C.; Rodó, C.; Valle, L.; Romero, A.; Juan, M.; Rodríguez, A.; Muñoz, B.; Santacruz, B.; et al. Cervical pessary in pregnant women with a short cervix (PECEP): An open-label randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2012, 379, 1800–1806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoffman, M.K.; Clifton, R.G.; Biggio, J.R.; VanDorsten, J.P.; Tita, A.T.; Saade, G.; Metz, T.D.; Esplin, M.S.; Longo, M.; Blackwell, S.C.; et al. Cervical Pessary for Prevention of Preterm Birth in Individuals with a Short Cervix: The TOPS Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA 2023, 330, 340–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicolaides, K.H.; Syngelaki, A.; Poon, L.C.; Picciarelli, G.; Tul, N.; Zamprakou, A.; Skyfta, E.; Parra-Cordero, M.; Palma-Dias, R.; Rodriguez Calvo, J. A Randomized Trial of a Cervical Pessary to Prevent Preterm Singleton Birth. N. Engl. J. Med. 2016, 374, 1044–1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saccone, G.; Maruotti, G.M.; Giudicepietro, A.; Martinelli, P. Effect of cervical pessary on spontaneous preterm birth in women with singleton pregnancies and short cervical length: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2017, 318, 2317–2324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dugoff, L.; Berghella, V.; Sehdev, H.; Mackeen, A.D.; Goetzl, L.; Ludmir, J. Prevention of preterm birth with pessary in singletons (PoPPS): Randomized controlled trial. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 2018, 51, 573–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daskalakis, G.; Papantoniou, N.; Mesogitis, S.; Antsaklis, A. Management of cervical insufficiency and bulging fetal membranes. Obstet. Gynecol. 2006, 107, 221–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stupin, J.H.; David, M.; Siedentopf, J.P.; Dudenhausen, J.W. Emergency cerclage versus bed rest for amniotic sac prolapse before 27 gestational weeks. A retrospective, comparative study of 161 women. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2008, 139, 32–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aoki, S.; Ohnuma, E.; Kurasawa, K.; Okuda, M.; Takahashi, T.; Hirahara, F. Emergency cerclage versus expectant management for prolapsed fetal membranes: A retrospective, comparative study. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. Res. 2014, 40, 381–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ventolini, G.; Genrich, T.J.; Roth, J.; Neiger, R. Pregnancy outcome after placement of ‘rescue’ Shirodkar cerclage. J. Perinatol. 2009, 29, 276–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thakur, M.; Jenkins, S.M.; Mahajan, K. Cervical Insufficiency. In StatPearls [Internet]; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2025. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK525954/ (accessed on 11 October 2025).

- Kacerovsky, M.; Stranik, J.; Matulova, J.; Chalupska, M.; Mls, J.; Faist, T.; Hornychova, H.; Kukla, R.; Bolehovska, R.; Bostik, P.; et al. Clinical characteristics of colonization of the amniotic cavity in women with preterm prelabor rupture of membranes, a retrospective study. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 5062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mays, J.K.; Figueroa, R.; Shah, J.; Khakoo, H.; Kaminsky, S.; Tejani, N. Amniocentesis for selection before rescue cerclage. Obstet. Gynecol. 2000, 95, 652–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kusanovic, J.P.; Espinoza, J.; Romero, R.; Gonçalves, L.F.; Nien, J.K.; Soto, E.; Khalek, N.; Camacho, N.; Hendler, I.; Mittal, P.; et al. Clinical significance of the presence of amniotic fluid ‘sludge’ in asymptomatic patients at high risk for spontaneous preterm delivery. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 2007, 30, 706–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehsanipoor, R.M.; Seligman, N.S.; Saccone, G.; Szymanski, L.M.; Wissinger, C.; Werner, E.F.; Berghella, V. Physical examination–indicated cerclage: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Obstet. Gynecol. 2015, 126, 125–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Debby, A.; Sadan, O.; Glezerman, M.; Golan, A. Favorable outcome following emergency second trimester cerclage. Int. J. Gynaecol. Obstet. 2007, 96, 16–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Gao, J.; Liu, J.; Hu, J.; Chen, X.; He, J.; Tang, Y.; Liu, X.; Cao, Y. Perinatal Outcomes and Risk Factors for Preterm Birth in Twin Pregnancies in a Chinese Population: A Multi-center Retrospective Study. Front. Med. 2021, 8, 657862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olisova, K.; Sao, C.H.; Lussier, E.C.; Sung, C.Y.; Wang, P.H.; Yeh, C.C.; Chang, T.Y. Ultrasonographic cervical length screening at 20-24 weeks of gestation in twin pregnancies for prediction of spontaneous preterm birth: A 10-year Taiwanese cohort. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0292533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skentou, C.; Souka, A.P.; To, M.S.; Liao, A.W.; Nicolaides, K.H. Prediction of preterm delivery in twins by cervical assessment at 23 weeks. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 2001, 17, 7–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stock, S.; Norman, J. Preterm and term labour in multiple pregnancies. Semin. Fetal Neonatal Med. 2010, 15, 336–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Romero, R.; Conde-Agudelo, A.; El-Refaie, W.; Rode, L.; Brizot, M.L.; Cetingoz, E.; Serra, V.; Da Fonseca, E.; Abdelhafez, M.S.; Tabor, A.; et al. Vaginal progesterone decreases preterm birth and neonatal morbidity and mortality in women with a twin gestation and a short cervix: An updated meta-analysis of individual patient data. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 2017, 49, 303–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rode, L.; Klein, K.; Nicolaides, K.H.; Krampl-Bettelheim, E.; Tabor, A. Prevention of preterm delivery in twin gestations (PREDICT): A multicenter, randomized, placebo-controlled trial on the effect of vaginal micronized progesterone. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 2011, 38, 272–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serra, V.; Perales, A.; Meseguer, J.; Parrilla, J.J.; Lara, C.; Bellver, J.; Grifol, R.; Alcover, I.; Sala, M.; Martínez-Escoriza, J.C.; et al. Increased doses of vaginal progesterone for the prevention of preterm birth in twin pregnancies: A randomised controlled double-blind multicentre trial. BJOG 2013, 120, 50–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rouse, D.J.; Caritis, S.N.; Peaceman, A.M.; Sciscione, A.; Thom, E.A.; Spong, C.Y.; Varner, M.; Malone, F.; Iams, J.D.; Mercer, B.M.; et al. A trial of 17 alpha-hydroxyprogesterone caproate to prevent prematurity in twins. N. Engl. J. Med. 2007, 357, 454–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rafael, T.J.; Berghella, V.; Alfirevic, Z. Cervical stitch (cerclage) for preventing preterm birth in multiple pregnancy. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2014, 9, CD009166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saccone, G.; Rust, O.; Althuisius, S.; Roman, A.; Berghella, V. Cerclage for short cervix in twin pregnancies: Systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized trials using individual patient-level data. Acta Obstet. Gynecol. Scand. 2015, 94, 352–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 169: Multifetal gestations: Twin, triplet, and higher-order multifetal pregnancies. Obstet. Gynecol. 2016, 128, e131–e146. [Google Scholar]

- Liem, S.; Schuit, E.; Hegeman, M.; de Boer, K.; Bloemenkamp, K.; Bekedam, D.; Wouters, M.; Hasaart, T.; Oude Rengerink, K.; Roumen, F.; et al. Cervical pessaries for prevention of preterm birth in women with a multiple pregnancy (ProTWIN): A multicentre, open-label randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2013, 382, 1341–1349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berghella, V. Universal cervical length screening: Yes! Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. MFM 2024, 6, 101347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khalifeh, A.; Berghella, V. Universal cervical length screening in singleton gestations without a previous preterm birth: Ten reasons why it should be implemented. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2016, 214, 603.e1–603.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orzechowski, K.M.; Boelig, R.C.; Baxter, J.K.; Berghella, V. A universal transvaginal cervical length screening program for preterm birth prevention. Obstet. Gynecol. 2014, 124, 520–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Einerson, B.D.; Grobman, W.A.; Miller, E.S. Cost-effectiveness of risk-based screening for cervical length to prevent preterm birth. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2016, 215, 100.e1–100.e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filce, C.; Hyett, J.; Sahota, D.; Wilson, K.; McLennan, A. Developing a quality assurance program for transvaginal cervical length measurement at 18–21 weeks’ gestation. Aust. N. Z. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2020, 60, 55–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cahill, A.G.; Odibo, A.O.; Caughey, A.B.; Stamilio, D.M.; Hassan, S.S.; Macones, G.A.; Romero, R. Universal cervical length screening and treatment with vaginal progesterone to prevent preterm birth: A decision and economic analysis. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2010, 202, 548.e1–548.e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Zhong, Q.; Li, L.; Chen, Y.; Tang, C.; Liu, T.; Luo, S.; Xiong, J.; Wang, L. Development and validation of a prediction model on spontaneous preterm birth in twin pregnancy: A retrospective cohort study. Reprod. Health 2023, 20, 187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menon, R.; Torloni, M.R.; Voltolini, C.; Torricelli, M.; Merialdi, M.; Betran, A.P.; Widmer, M.; Allen, T.; Davydova, I.; Khodjaeva, Z.; et al. Biomarkers of spontaneous preterm birth: An overview of the literature in the last four decades. Reprod. Sci. 2011, 18, 1046–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuhrt, K.; Hezelgrave, N.; Foster, C.; Seed, P.T.; Shennan, A. Development and validation of a tool incorporating cervical length and quantitative fetal fibronectin to predict spontaneous preterm birth in asymptomatic high-risk women. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 2016, 47, 104–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elovitz, M.A.; Brown, A.G.; Breen, K.; Anton, L.; Maubert, M.; Burd, I. Intrauterine inflammation, insufficient to induce parturition, still evokes fetal and neonatal brain injury. Int. J. Dev. Neurosci. 2011, 29, 663–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oskovi Kaplan, Z.A.; Ozgu-Erdinc, A.S. Prediction of Preterm Birth: Maternal Characteristics, Ultrasound Markers, and Biomarkers: An Updated Overview. J. Pregnancy 2018, 2018, 8367571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarca, A.L.; Fitzgerald, W.; Chaemsaithong, P.; Xu, Z.; Hassan, S.S.; Grivel, J.C.; Gomez-Lopez, N.; Panaitescu, B.; Pacora, P.; Maymon, E.; et al. The cytokine network in women with an asymptomatic short cervix and the risk of preterm delivery. Am. J. Reprod. Immunol. 2017, 78, e12686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, A.; Darmstadt, G.L.; Gruber, S.; Foeller, M.E.; Carmichael, S.L.; Stevenson, D.K.; Shaw, G.M. Application of machine-learning to predict early spontaneous preterm birth among nulliparous non-Hispanic black and white women. Ann. Epidemiol. 2018, 28, 783–789.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morken, N.H.; Källen, K.; Jacobsson, B. Outcomes of preterm children according to type of delivery onset: A nationwide population-based study. Paediatr. Perinat. Epidemiol. 2007, 21, 458–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bastek, J.A.; Hirshberg, A.; Chandrasekaran, S.; Owen, C.M.; Heiser, L.M.; Araujo, B.A.; McShea, M.A.; Ryan, M.E.; Elovitz, M.A. Biomarkers and cervical length to predict spontaneous preterm birth in asymptomatic high-risk women. Obstet. Gynecol. 2013, 122, 283–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Honest, H.; Bachmann, L.M.; Coomarasamy, A.; Gupta, J.K.; Kleijnen, J.; Khan, K.S. Accuracy of cervical transvaginal sonography in predicting preterm birth: A systematic review. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 2003, 22, 305–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gomez-Lopez, N.; StLouis, D.; Lehr, M.A.; Sanchez-Rodriguez, E.N.; Arenas-Hernandez, M. Immune cells in term and preterm labor. Cell Mol. Immunol. 2014, 11, 571–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strauss, J.F. Extracellular matrix dynamics and fetal membrane rupture. Reprod. Sci. 2013, 20, 140–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Diagnostic Category | Specific Clinical Criteria | Cervical Length Threshold | Evidence-Based Management | Evidence Level | Typical Success Rate |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| History-Based [1,5,53,54] | ≥2 consecutive second-trimester losses (14–27 weeks) or extremely preterm births <28 weeks with painless cervical dilation and minimal contractions | Not applicable | History-indicated cerclage at 12–16 weeks | Grade B | 70–90% |

| Ultrasound-Based [10,53,54,55,57,58] | Previous spontaneous preterm birth <37 weeks + current pregnancy cervical length ≤25 mm before 24 weeks | ≤25 mm | Ultrasound-indicated cerclage ± progesterone | Grade A | 75–85% |

| Physical Examination-Based [1,53,54] | Cervical dilation ≥1 cm and effacement ≥50% at 14–27 weeks without adequate uterine contractions | Variable with advanced dilation | Emergency cerclage after infection exclusion | Grade C | 35–70% |

| Asymptomatic Short Cervix [10,53,54,55] | Incidental finding on routine screening, no history of spontaneous preterm birth <37 weeks | ≤20 mm (definitive) 21–25 mm (discretionary) | Vaginal progesterone with serial monitoring | Grade A | 65–80% |

| Intervention Strategy | Patient Population | Preterm Birth <34 Weeks | Preterm Birth <32 Weeks | Relative Risk (95% CI) | Number Needed to Treat | Major Complications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ultrasound-Indicated Cerclage [87] | Prior PTB < 37 weeks + CL ≤ 25 mm before 24 weeks | 15–18% vs. 26–30% * | 8–12% vs. 18–22% † | 0.70 (0.55–0.89) | 8 | 2–5% |

| History-Indicated Cerclage [93] | ≥2 s-trimester losses or PTB < 28 weeks | 10–15% vs. 25–35% ‡ | 5–8% vs. 15–20% | 0.55 (0.40–0.75) | 5 | 3–8% |

| Combined Cerclage + Progesterone [96,97] | High-risk (prior PTB or CL ≤ 25 mm) | 11% vs. 24% § | 6% vs. 15% | 0.45 (0.29–0.69) | 8 | 2–6% |

| Progesterone Alone [78] | CL ≤25 mm, no prior PTB | 18–22% vs. 28–35% | 10–14% vs. 20–25% | 0.70 (0.55–0.90) | 9 | <1% |

| Clinical Presentation Factor | Successful Pregnancy Prolongation (%) | Mean Gestational Age at Delivery (Weeks) | Neonatal Survival Rate (%) | Major Maternal Complications (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cervical Dilation 2–3 cm [115] | 75–85 | 32–34 | 80–90 | 5–10 |

| Cervical Dilation 4–6 cm [115] | 45–60 | 28–30 | 60–75 | 10–15 |

| Visible Membrane Prolapse [116] | 35–50 | 26–28 | 50–65 | 15–25 |

| Negative Amniocentesis [113] | 70–80 | 31–33 | 80–85 | 5–12 |

| Positive Amniocentesis [113] | 20–30 | 24–26 | 30–40 | 20–35 |

| Intervention Type | Key Studies | Total Sample Size | Primary Outcome | Result Summary | Relative Risk (95% CI) | Current Recommendation | Evidence Quality |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vaginal Progesterone | PREDICT trial [122] | 500+ twin pregnancies | PTB < 34 weeks | No significant benefit | 1.04 (0.79–1.37) | Not recommended | High |

| 17-OHPC Injections | Rouse et al. [124] | 661 twin pregnancies | PTB < 35 weeks | No significant benefit | 0.99 (0.81–1.21) | Not recommended | High |

| Cervical Pessary | ProTWIN trial [128] | 813 twin pregnancies | Composite poor outcome | No significant benefit | 1.02 (0.84–1.24) | Not recommended | Moderate |

| Cervical Cerclage | Meta-analyses [125,126] | 200+ twin pregnancies | PTB < 34 weeks | Potential harm | 1.23 (0.98–1.54) | Contraindicated | Moderate |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Baroutis, D.; Katsianou, E.; Fragiskos, I.; Papakonstantinou, M.-E.; Koukoumpanis, K.; Giannakaki, A.-G.; Tzanis, A.A.; Pergialiotis, V.; Sindos, M.; Daskalakis, G. Spectrum of Cervical Insufficiency: Management Strategies from Asymptomatic Shortening to Emergent Membrane Prolapse. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 8506. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238506

Baroutis D, Katsianou E, Fragiskos I, Papakonstantinou M-E, Koukoumpanis K, Giannakaki A-G, Tzanis AA, Pergialiotis V, Sindos M, Daskalakis G. Spectrum of Cervical Insufficiency: Management Strategies from Asymptomatic Shortening to Emergent Membrane Prolapse. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(23):8506. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238506

Chicago/Turabian StyleBaroutis, Dimitris, Eleni Katsianou, Ioannis Fragiskos, Maria-Eleni Papakonstantinou, Konstantinos Koukoumpanis, Aikaterini-Gavriela Giannakaki, Alexander A. Tzanis, Vasilios Pergialiotis, Michael Sindos, and George Daskalakis. 2025. "Spectrum of Cervical Insufficiency: Management Strategies from Asymptomatic Shortening to Emergent Membrane Prolapse" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 23: 8506. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238506

APA StyleBaroutis, D., Katsianou, E., Fragiskos, I., Papakonstantinou, M.-E., Koukoumpanis, K., Giannakaki, A.-G., Tzanis, A. A., Pergialiotis, V., Sindos, M., & Daskalakis, G. (2025). Spectrum of Cervical Insufficiency: Management Strategies from Asymptomatic Shortening to Emergent Membrane Prolapse. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(23), 8506. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238506