Abstract

Objective: The objective of this study is the investigation of uterine artery Doppler studies in twin pregnancies. Methods: This retrospective cohort study included 554 twin pregnancies. All women underwent measurement using the mean uterine artery pulsatility index (UTPI) in gestational weeks 11+0–13+6 and 19+0–22+6 for risk assessment regarding the occurrence of preeclampsia and adverse obstetric outcomes. Results: Out of the 554 included women, a total of 51 women (9.2%) developed preeclampsia: 12 women (2.2%) developed early preeclampsia and 39 patients (7.0%) developed late preeclampsia. Adverse pregnancy outcomes occurred in 147 women (26.5%). The optimum cut-off for the mean UTPI to predict preeclampsia was calculated for gestational weeks 11+0–13+6 (UTPI > 1.682) and 19+0–22+6 (UTPI > 1.187). Between gestational weeks 11+0 and 13+6, the risk of developing preeclampsia was approximately 1.5 times higher when the mean UTPI was above the established cut-off. The risk of early preeclampsia increased 2.5-fold, and that of adverse pregnancy outcomes increased 1.5-fold. At 19+0 to 22+6 weeks, the preeclampsia risk doubled when the mean UTPI exceeded the cut-off. The risk increased 4-fold for early preeclampsia and 1.5-fold for adverse pregnancy outcomes. Regression analyses revealed that a mean UTPI above the set cut-off at both time points was significantly associated with preeclampsia, early preeclampsia, and adverse pregnancy outcomes. Conclusions: The best prediction for early preeclampsia can be achieved using a two-tailed screening approach that combines mean UTPI measurements taken at gestational weeks 11+0–13+6 and 19+0–22+6.

1. Introduction

A substantial increase in twin pregnancies has been observed over the past few decades [1,2,3,4,5,6]. It is well known that multiple pregnancies are associated with higher obstetric complication rates, which compromises both the fetuses and mother [7,8].

It is well documented that pregnancy-related hypertensive disorders constitute a substantial cause of fetal and maternal morbidity and mortality globally [9,10]. Several studies have highlighted an increased risk of pregnancy-related hypertensive disorders in multifetal gestations [11,12,13,14,15]. The probability of pregnancy-related hypertensive disorders positively correlates with the number of fetuses carried out, and these disorders affect approximately 6.5% of all singleton pregnancies, 12.7% of twin pregnancies, and 20% of all triplet pregnancies [16]. Preeclampsia (PE) is defined as hypertensive blood pressure values which first occur after the 20th week of gestation with new-onset proteinuria. In the absence of proteinuria, other diagnostic features that are typical for organ dysfunction associated with preeclampsia, which include impaired liver function, thrombocytopenia, severe persistent pain in the right upper abdomen, renal insufficiency, pulmonary edema, fetal growth restriction (FGR), headache, and new-onset of visual symptoms, may confirm the diagnosis [10,17,18].

The pathogenesis of PE is not completely clarified yet. The most widespread hypothesis is based on an abnormal placentation [19]. The uterine arteries play a key role in the vascularization of the uterus. They branch into the arcuate arteries within the superficial myometrium, which give rise to radial arteries. These, in turn, lead to the basal arteries and terminate as spiral arteries. Throughout pregnancy, these spiral arteries provide blood flow to the intervillous space of the placenta. Remodeling of the uteroplacental vascular system occurs throughout different stages of pregnancy. This remodeling is essential for the reduction in vascular resistance to occur, which enables an increase in uterine blood flow, and is therefore necessary for successful placental implantation and normal placental function [20,21]. In some pregnancies, impaired remodeling of the maternal spiral arteries occurs early in gestation [19]. This causes a dysfunctional uteroplacental circulation, hypoxia, and placental apoptosis and necrosis [22,23,24]. Ultimately, oxidative stress causes endothelial dysfunction and an exuberant inflammatory response through the release of various angiogenic factors [22,25]. A maladaptive response with a reduced dilatory ability causes hypertension and increased capillary leakage, which induces proteinuria [22,26].

It is assumed that the decreased vascular capacitance and increased uteroplacental vascular resistance cause changes in the waveform of the uterine arteries which can be detected by Doppler examinations. Doppler studies of the uterine arteries allow a reproducible, non-invasive examination of placentation [21]. Several studies showed an association between abnormal Doppler examinations in the first and second trimester and the development of PE or FGR in ongoing pregnancy [27,28,29,30,31,32,33]. Initial studies in twin pregnancies have demonstrated a similar association; however, the mean uterine artery pulsatility index was significantly lower in these studies [14,34,35,36]. In their meta-analysis, Cao et al. reported a sensitivity of 65% and a specificity of 88% for the prediction of preeclampsia [37]. In contrast, studies in twin pregnancies reported lower sensitivities (33.3–36.4%) and higher specificities (88–96.7%) [38,39].

Early detection of impaired placental perfusion and development of PE at an early stage of pregnancy may be of great interest due to its potential to enable a prophylactic treatment at a time when the effect has been demonstrated.

The aim of this work was to investigate uterine artery Doppler examinations in twin pregnancies at the first and second trimester in relationship to hypertensive disorders.

2. Materials and Methods

This was a retrospective study to evaluate the use of the mean uterine artery pulsatility index (UTPI) in gestational weeks 11+0–13+6 and 19+0–22+6 for risk evaluation regarding the onset of preeclampsia or other obstetric adverse outcomes in twin pregnancies, conducted at the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology of the Medical University of Vienna, a tertiary care center, over a study period of 4 years. Out of the 585 women with uncomplicated twin pregnancies above the age of 18 years who received measurements of their UTPI in gestational weeks 11+0–13+6, a total of 31 patients were excluded. Thirteen of them did not have a documented ultrasound scan at gestational weeks 19+0–22+6, five women had missing UTPI measurements at gestational weeks 11+0–13+6 or 19+0–22+6, three women had missing fetal outcome data, five women had missing maternal characteristics data, one woman had an abortion with mifepristone at gestational week 22+6, one woman had feticide of one fetus due to trisomy 21, three women had a miscarriage. The remaining 554 patients had measurement of both uterine arteries at gestational weeks 11+0–13+6 and 19+0–22+6, and complete maternal characteristics and fetal outcome data. Ultrasound was performed with Voluson E8 Expert, a transabdominal RAB 4-8-D convex probe was used–alternatively, and ultrasound was conducted with General Electric Healthcare E10 with a transabdominal RM 6C convex probe. In addition to the first-trimester screening, ultrasound examinations according to the clinic’s operating standard for twin pregnancies were conducted. Monochorionic twins were examined every two weeks from 16+0 weeks of gestation onwards and dichorionic twins were examined every four weeks. First-trimester screening was performed between 11+0 and 13+6 weeks of gestation, and standardized criteria according to the Fetal Medicine Foundation (London) were followed. At this appointment, chorionicity was determined by visualizing the lambda sign in DC twin pregnancies and the T-sign in MC twin gestations. Initially, gestational age was initially calculated regarding the first day of the last normal menstruation. By measuring the crown–rump-length (CRL) of the larger twin it was then adjusted. Additionally, the women received an anomaly scan between 20+0 and 23+6 weeks of gestation. Either transabdominal or transvaginal approach was conducted for measuring the pulsatility index (PI) of the uterine arteries. For transabdominal measurement, the uterine arteries were identified beside the cervix by high-velocity blood flow using color Doppler in the longitudinal plane. The angle of insonation was intended to be < 30° and the measurement was obtained as close as possible to the internal cervical os. The PI was measured when at least three identical waveforms were obtained. Transvaginal assessment of UTPI was done using the same principles. At 19+0–22+6 weeks, the PI of both uterine arteries was measured by transabdominal ultrasound. Data of included women with twin gestations were collected from Viewpoint® software 5.6.28 (GE Healthcare, Wessling, Germany). The following data were extracted: age, weight, height, conception mode, gestational week at delivery, nicotine consumption, parity, placental abruption, stillbirth, UTPI in gestational weeks 11+0–13+6 and 19+0–22+6, chorionicity, preexisting chronic hypertension, gestational hypertension, early PE, late PE, HELLP, eclampsia, FGR, and intrauterine fetal death (IUFD).

Preeclampsia was defined in accordance with the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists as a newly onset blood pressure ≥140/90 mmHg measured over 20 weeks of gestation on two different occasions at least 4 h apart in women with a previously normal blood pressure, or a blood pressure ≥160/110 and proteinuria. Definition of proteinuria included ≥300 mg protein excretion in the 24 h urine collection, a protein/creatinine ratio of 0.3 mg/dL, or, alternatively, a urine dipstick reading of 2+ (this method was used only if other quantitative methods were not available). In women with newly diagnosed hypertension, preeclampsia was diagnosed if any of the following occurred—even in the absence of proteinuria: a platelet count below 100,000/μL, serum creatinine above 1.1 mg/dL, liver transaminase levels at least twice the normal limit, pulmonary edema, FGR, or neurological symptoms such as visual disturbances or headaches. Gestational hypertension was defined as blood pressure ≥140/90 mmHg in the absence of significant proteinuria after 20 weeks of gestation [10]. The primary endpoint of this study was the development of PE, which was subdivided into early and late PE. Early PE is defined as PE diagnosis before 34+0 weeks of gestation and late PE as PE diagnosis after 34+0 weeks of gestation. The secondary endpoint was defined as occurrence of adverse pregnancy outcome, which includes preterm birth <32+0 weeks of gestation, PE, gestational hypertension, FGR, stillbirth, placental abruption, HELLP syndrome, and eclampsia. None of the patients received low-dose aspirin for preeclampsia prophylaxis. When indicated, patients with hypertensive pregnancy disorders received antihypertensive treatment (e.g., methyldopa, enalapril, nifedipine) for blood pressure control, in accordance with a local clinical guideline. In cases of preterm birth before 34+0 weeks of gestation, patients received antenatal corticosteroids for fetal lung maturation, and, in cases before 32+0 weeks, they received neuroprotection with magnesium sulfate. The Ethical Review Board of the Medical University of Vienna (EK Nr: 2071/2018) approved the conduction of this study. It was performed according to the standards of the Helsinki Declaration. Declaration of consent was obtained at registration according to the department’s operating standards. Data analysis was conducted using SPSS 26.0 for Mac (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). A Kolmogorov–Smirnov test was used to verify data distribution. Variables that were normally distributed are presented as means (± standard deviation (SD)), categorical data as percentages. Further statistical tests including Chi-square test, McNemar test, and logistic multiple regression analyses were used. Logistic regression was obtained using the backward selection with likelihood ratio. The Hosmer and Lemeshow test was used. In addition, a receiver operating characteristics (ROC) curve was created to calculate sensitivity and specificity. The cut-off for mean PI was separately defined according to the Youden index. We calculated sensitivity, specificity, and relative risk with 95% confidence interval (95% CI). All tests were two tailed, p-value ≤ 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

Out of the 554 women included in this retrospective analysis, a total of 51 women (9.2%) developed PE. Twelve women (2.2%) developed early PE and 39 patients (7.0%) developed late PE. An adverse pregnancy outcome (including preterm birth < 32+0 weeks of gestation, PE, gestational hypertension, FGR, stillbirth, placental abruption, HELLP syndrome, and eclampsia) occurred in 147 women (26.5%). Clinical characteristics of the subgroups (PE, early PE, late PE, and adverse pregnancy outcome) are presented in Table 1 and Table 2.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics of patients with preeclampsia, early preeclampsia, and late preeclampsia and control group.

Table 2.

Patient characteristics of patients with adverse pregnancy outcome and control group.

In the observed monochorionic twin pregnancies, 14.7% developed PE, compared to 9.8% in the dichorionic twin gestations. The mean maternal age was 32 years in the control group and 34 in the PE cohort. The median body mass index (BMI) was 22.7 kg/m2 in the women without PE and 23.5 kg/m2 in those with PE. The control group consisted of 57.1% nullipara women, whereas the PE group included 74.5%. The control cohort had 63.4% spontaneous conceptions. Assisted reproductive technology (ART) was used in 36.6%. In the PE group, 47.1% of the women had a spontaneous conception and ART was performed in 52.9% of the patients. The group of women without PE had 70.0% DC gestations and 30.0% MC twins. The PE group consisted of 78.4% DC gestations and 21.6% MC twins. The median gestational age of the neonates that were delivered was 36.7 weeks in the control group, whereas it was 36.0 weeks in the PE cohort.

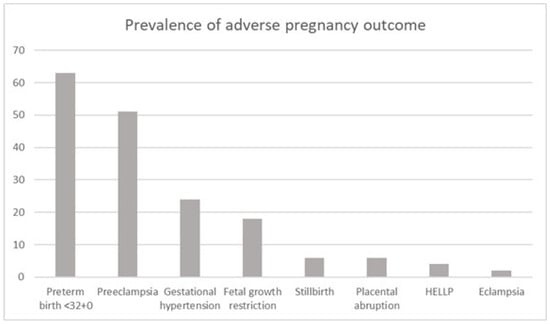

Patient characteristics of the subgroup affected by adverse pregnancy outcome (including preterm birth <32+0 weeks of gestation, PE, gestational hypertension, FGR, stillbirth, placental abruption, HELLP syndrome, and eclampsia) are outlined in Table 2. The prevalence of the individual parameters within the adverse pregnancy outcome group is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Cumulative prevalence (percentage) in the adverse pregnancy outcome group.

As seen in Table 3, the median mean UTPI in gestational weeks 11+0–13+6 in the women without PE was 1.23 (range of 0.36–2.97) and it was 1.26 (range of 0.54–2.57) in the women with PE. In gestational weeks 19+0–22+6, the women without PE had a median mean UTPI of 0.8 (range of 0.33–1.78) and the women with PE had a mean UTPI of 0.81 (range of 0.47–1.56).

Table 3.

Pulsatility index for the uterine arteries for gestational weeks 11+0–13+6 and 19+0–22+6 in the control group and the preeclampsia group.

The median mean UTPI in gestational weeks 11+0–13+6 in the MC twins was 1.38 (range 0.54–2.45) and it was 1.24 (range 0.36–2.97) in the DC twins. In gestational weeks 19+0–22+6, the MC pregnancies had a median mean UTPI of 0.88 (range 0.47–1.76) and the DC pregnancies had a median mean UTPI of 0.82 (range 0.33–1.78) (Table 4).

Table 4.

Pulsatility index of the uterine arteries for gestational weeks 11+0–13+6 and 19+0–22+6 in monochorionic and dichorionic twin pregnancies.

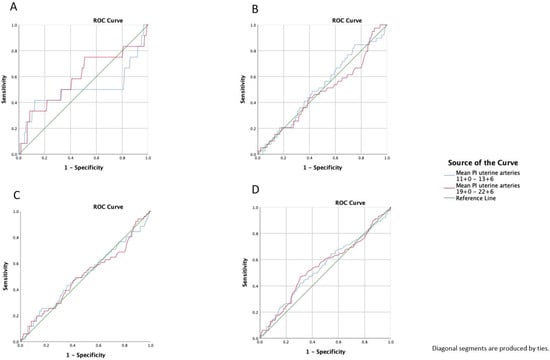

The detection rates of pregnancies complicated by PE or an adverse pregnancy outcome (including preterm birth <32+0 weeks of gestation, PE, gestational hypertension, FGR, stillbirth, placental abruption, HELLP syndrome, and eclampsia) were calculated, and ROC curves that predicted PE, early PE, late PE, and adverse obstetric outcomes in gestational weeks 11+0–13+6 and 19+0–22+6 were constructed. None of the individual adverse pregnancy outcomes, except for PE, were significantly associated with the uterine artery Doppler measurements. We calculated the area under the curve (AUC) for each curve. For the prediction of PE, the AUC was 0.512 for gestational weeks 11+0–13+6 and 0.504 for gestational weeks 19+0–22+6. The AUC for prediction of early PE by UTPI was 0.502 for the gestational weeks 11+0–13+6 and 0.589 for the gestational weeks 19+0–22+6. For late PE, the AUC was 0.515 for 11+0–13+6 weeks of gestation and 0.467 for 19+0–22+6 weeks of gestation. For adverse pregnancy outcomes, the AUC at 11+0–13+6 weeks of gestation was 0.543 and it was 0.547 for the weeks 19+0–22+6 (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Receiver operating characteristics curve (ROC) prediction (A): early preeclampsia, (B): late preeclampsia, (C): preeclampsia, and (D): adverse pregnancy outcome with a mean pulsatility index of the uterine arteries at 11+0–13+6 and 19+0–22+6 weeks of gestation; adverse pregnancy includes preterm birth <32+0 weeks of gestation, PE, gestational hypertension, FGR, stillbirth, placental abruption, HELLP syndrome, and eclampsia.

The Youden index was defined for all points on the ROC curves for the prediction of PE, alongside the mean UTPI for gestational weeks 11+0–13+6 and 19+0–22+6. The optimum cut-off for the mean UTPI was selected for the gestational weeks 11+0–13+6 and 19+0–22+6, using the highest Youden index. For the gestational weeks 11+0–13+6, the cut-off was set at a mean UTPI of 1.682 and, for the gestational weeks 19+0–22+6, it was set at 1.187.

The sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value, negative predictive value, and likelihood ratio with a 95% confidence interval for PE, early PE, late PE, and adverse pregnancy outcome (including preterm birth <32+0 weeks of gestation, PE, gestational hypertension, FGR, stillbirth, placental abruption, HELLP syndrome, and eclampsia) were calculated for gestational weeks 11+0–13+6 and 19+0–22+6, as shown in Table 5 and Table 6.

Table 5.

The predictive value of a mean uterine artery pulsatility index >1.682 at gestational weeks 11+0–13+6 for preeclampsia, early preeclampsia, late preeclampsia, and adverse pregnancy outcome.

Table 6.

The predictive value of a mean uterine artery pulsatility index >1.187 at gestational weeks 19+0–22+6 for preeclampsia, early preeclampsia, late preeclampsia, and adverse pregnancy outcome.

In the gestational weeks 11+0–13+6, there was a 1.5-fold increased risk for developing PE with a mean UTPI above the set cut-off. The risk of early PE was increased 2.5-fold, and that of an adverse pregnancy outcome was increased 1.5-fold. For late PE, there was only a slightly increased risk, by 1.2-fold, if the mean UTPI was above the cut-off.

In the gestational weeks 19+0–22+6, the risk of developing PE was increased 2-fold if the mean UTPI was above the set cut-off. For early PE, the risk was increased 4-fold and, for adverse pregnancy outcome, it was increased 1.5-fold. Again, there was only a slightly increased risk (1.1-fold) of developing late PE with a mean UTPI above the cut-off.

To compare testing in the gestational weeks 11+0–13+6 and 19+0–22+6, crosstables and the McNemar test was used (Table 7).

Table 7.

Crosstable for McNemar test for mean pulsatility index of the uterine arteries (UTPI) above the cut-off (1.188) in gestational weeks 19+0–22+6 and mean UTPI above the cut-off (1.683) in gestational weeks 11+0–13+6.

The McNemar test is highly significant (p < 0.001) for measurement of the mean cut-off UTPI in gestational weeks 11+0–13+6 and 19+0–22+6. Therefore, there is a difference between these measurements.

For women who developed PE, the McNemar test for measurement of the mean cut-off UTPI in gestational weeks 11+0–13+6 and 19+0–22+6 was not statistically significant (p = 0.18). There seems to be no link between the first and second measurements in women with PE.

The McNemar test is highly significant (p < 0.001) for women without PE regarding the mean cut-off UTPI in gestational weeks 11+0–13+6 and 19+0–22+6. Thus, there is a link between measurements of the UTPI in these gestational weeks.

The following parameters were included for the regression analysis: maternal age, maternal BMI, smoking habits, nulliparity, and UTPI in gestational weeks 11+0–13+6 > 1.682 and 19+0–22+6 > 1.187. The analysis revealed that increases in the maternal age, maternal BMI, smoking habits, and/or mean PI of the uterine arteries at both times (gestational weeks 11+0–13+6 and 19+0–22+6) were associated with preeclampsia, early preeclampsia, late preeclampsia, and/or adverse pregnancy outcome (Table 8).

Table 8.

Predictors of adverse obstetric outcomes.

4. Discussion

In our study, we investigated the predictive value of the mean UTPI within the first and second-trimester screening for preeclampsia and adverse pregnancy outcomes in twin pregnancies. Early preeclampsia can be identified more accurately than late preeclampsia. A combination of the mean UTPIs of the first and second trimesters could most effectively forecast preeclampsia.

Various studies have investigated the use of uterine artery Doppler examinations to predict preeclampsia, growth restriction, and unfavorable pregnancy outcomes in singleton pregnancies [27,28,31,40,41,42,43,44,45]. Similar studies have been conducted on twin pregnancies [14,35,36,38,39,46,47,48,49,50]. The current study demonstrates that the mean UTPI at gestational weeks 11+0–13+6 and 19+0–22+6 is lower than previously reported in singleton pregnancies [40,51]. This has already been described by several other authors [14,35,36,38,39,46,48,49]. Rizzo et al. assume that the lower PI values result from a bigger placenta implantation site and altered maternal hemodynamics in twin pregnancies [14]. According to Geipel et al., the majority of UTPI values in twin pregnancies are below the 50th percentile of the reference range for singleton pregnancies [46]. Therefore, using reference values from singleton pregnancies could lead to a false-negative classification of patients at risk. Queirós et al. identified all cases of early-onset preeclampsia using the UTPI 90th percentile for twins. However, the detection rate dropped to 50% when singleton reference values were used [36]. Therefore, the use of twin-specific UTPI reference values for risk stratification should be considered.

In contrast to previous research, this study defined the cut-off for an elevated mean UTPI using the Youden index rather than the 95th percentile. The cut-off for the gestational ages 11+0–13+6 and 19+0–22+6 was set at 1.683 and 1.188, respectively. So far, no reference ranges for an elevated mean UTPI in twin gestations at gestational weeks 11+0–13+6 have been published. The first-trimester cut-off value described is lower than those used by Pilalis et al. and Gómez et al., who reported the 95th percentile of UTPI at 2.24–2.52 in singleton pregnancies [40,52]. Remarkably, our cut-off value used for gestational weeks 19+0–22+6 is comparable to the reference charts for the mean UTPI in twin pregnancies published by Geipel et al. They described an elevated mean UTPI above the 95th percentile, with values of 1.259 at 20 weeks, 1.206 at 21 weeks, 1.161 at 22 weeks, and 1.124 at 23 weeks. This results in an average cut-off for the mean UTPI in gestational weeks 19+0–22+6 of 1.188, which is nearly identical to the one used in our study [46].

Regardless of whether preeclampsia screening is performed between weeks 11+0 and 13+6, between weeks 19+0 and 22+6, or through a combination of both, our study shows that early preeclampsia can be predicted with the highest accuracy. Previously performed studies already outlined that the uterine artery Doppler is especially effective in identifying those women who will develop early-onset preeclampsia in comparison to late-onset preeclampsia [14,27,28,41,47,48].

We observed sensitivities and specificities of 41.7% and 83.4% at 11+0–13+6 weeks, 33.3% and 91.5% at 19+0–22+6 weeks, and 33.3% and 95.6% when using a combination of both. Recent studies on twin pregnancies utilizing twin references reported sensitivities of 33.3–36.4% and specificities of 88–96.7% for the prediction of preeclampsia [38,39]. The calculated likelihood ratio for a positive test for early preeclampsia was lower in gestational weeks 11+0–13+6 compared to weeks 19+0–22+6 and when both were combined. As the accuracy of predicting preeclampsia improves throughout pregnancy, using UTPI values from earlier gestational ages could result in lower predictive values. The combination of the two examinations resulted in the best likelihood ratio. This study is the first to present these results. Furthermore, in our study, we did not find any differences in the mean UTPI values concerning the chorionicity of the twins. Most previous studies have reported similar results [14,39,46,47,48], with only two suggesting the opposite [34,50].

There is broad consensus that multiple pregnancies carry a higher risk of hypertensive pregnancy disorders [11,13,16,53]. Identifying twin pregnancies at the highest risk of preeclampsia would facilitate more targeted and intensive prenatal care. We agree with Rizzo et al. that an isolated use of UTPI may have a limited role in the prediction of preeclampsia in twin pregnancies [14]. Recent studies on multi-marker screening models in twin pregnancies demonstrate good screening performance but show lower sensitivities and higher screen-positive rates compared to singleton pregnancies [34,54,55,56]. The question is whether screening after 16+0 weeks of gestation is too late for the stratification of low-dose aspirin therapy. Only one meta-analysis on preeclampsia prevention revealed a certain effect of aspirin in twin pregnancies. The results were inconsistent with those in singleton pregnancies, demonstrating a reduction in mild but not severe preeclampsia. Furthermore, the reduction was achieved when aspirin was initiated after 16+0 weeks of gestation but not before [57]. For this reason, a two-tailed test with better predictive value could more effectively identify patients who may benefit from aspirin therapy and intensive prenatal care.

As far as we know, we are the first to use a combination of the mean UTPI values in the first and second trimesters to predict preeclampsia in twin pregnancies. We consider this, along with the relatively large number of participants, to be a strength of our study. Nevertheless, several limitations should be addressed. First, this was a single-center retrospective study, which limits the generalizability of our findings to other settings and populations. Another limitation of this study is that we could not include the mean arterial blood pressure, nor biochemical markers such as pregnancy-associated plasma protein A, soluble Fms-like tyrosine kinase-1, and placental growth factor, or their ratio, in combination with uterine artery Doppler measurements to create predictive models for the development of preeclampsia.

5. Conclusions

We conclude that the best prediction for early-onset preeclampsia in twin pregnancies is achieved by using a two-tailed screening approach that combines UTPI measurements taken between gestational weeks 11+0–13+6 and 19+0–22+6.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.W.; methodology, C.W.; formal analysis, C.W.; investigation, T.A. and S.S.; data curation, T.A.; writing—original draft preparation, S.S. and C.W.; writing—review and editing, T.A., K.W. and E.K.; supervision, C.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Medical University of Vienna (2071/2018); Approval Date: 24 January 2019.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects included in the study. Before ultrasound examinations, all patients signed a consent form that the data may be used for retrospective studies.

Data Availability Statement

The data are not publicly available due to local data protection guide-lines.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| UTPI | uterine artery pulsatility index |

| PE | preeclampsia |

| MC | monochorionic |

| DC | dichorionic |

| PI | pulsatility index |

| FGR | fetal growth restriction |

| SD | standard deviation |

| CRL | crown-rump-length |

| ROC | receiver operating characteristics |

| CI | confidence interval |

| AUC | area under the curve |

| ART | assisted reproductive technology |

| IUFD | intrauterine fetal death |

| BMI | body mass index |

| NPV | negative predictive value |

| PPV | positive predictive value |

| LR+ | likelihood ratio of positive test result |

References

- Chauhan, S.P.; Scardo, J.A.; Hayes, E.; Abuhamad, A.Z.; Berghella, V. Twins: Prevalence, Problems, and Preterm Births. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2010, 203, 305–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ananth, C.V.; Joseph, K.S.; Demissie, K.; Vintzileos, A.M. Trends in Twin Preterm Birth Subtypes in the United States, 1989 through 2000: Impact on Perinatal Mortality. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2005, 193, 1076–1082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kogan, M.D.; Alexander, G.R.; Kotelchuck, M.; MacDorman, M.F.; Buekens, P.; Martin, J.A.; Papiernik, E. Trends in Twin Birth Outcomes and Prenatal Care Utilization in the United States, 1981–1997. JAMA 2000, 284, 335–341. [Google Scholar]

- Blondel, B.; Kogan, M.D.; Alexander, G.R.; Dattani, N.; Kramer, M.S.; Macfarlane, A.; Wen, S.W. The Impact of the Increasing Number of Multiple Births on the Rates of Preterm Birth and Low Birthweight: An International Study. Am. J. Public Health 2002, 92, 1323–1330. [Google Scholar]

- Eriksson, A.W.; Fellman, J. Temporal Trends in the Rates of Multiple Maternities in England and Wales. Twin Res. Hum. Genet. 2007, 10, 626–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imaizumi, Y. Trends of Twinning Rates in Ten Countries, 1972–1996. Acta Genet. Med. Gemellol. 1997, 46, 209–218. [Google Scholar]

- Committee on Practice Bulletins—Obstetrics. Society for Maternal–Fetal Medicine Practice Bulletin No. 169: Multifetal Gestations: Twin, Triplet, and Higher-Order Multifetal Pregnancies. Obstet. Gynecol. 2016, 128, e131–e146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wainstock, T.; Yoles, I.; Sergienko, R.; Sheiner, E. Twins vs Singletons-Long-Term Health Outcomes. Acta Obstet. Gynecol. Scand. 2023, 102, 1000–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leeman, L.; Dresang, L.T.; Fontaine, P. Hypertensive Disorders of Pregnancy. Am. Fam. Physician 2016, 93, 121–127. [Google Scholar]

- Espinoza, J.; Vidaeff, A.; Pettker, C.M.; Simhan, H. ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 202: Gestational Hypertension and Preeclampsia. Obstet. Gynecol. 2019, 133, e1–e25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sibai, B.M.; Hauth, J.; Caritis, S.; Lindheimer, M.D.; MacPherson, C.; Klebanoff, M.; VanDorsten, J.P.; Landon, M.; Miodovnik, M.; Paul, R.; et al. Hypertensive Disorders in Twin versus Singleton Gestations. National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Network of Maternal-Fetal Medicine Units. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2000, 182, 938–942. [Google Scholar]

- Lynch, A.; McDuffie, R.; Murphy, J.; Faber, K.; Orleans, M. Preeclampsia in Multiple Gestation: The Role of Assisted Reproductive Technologies. Obstet. Gynecol. 2002, 99, 445–451. [Google Scholar]

- Francisco, C.; Wright, D.; Benkő, Z.; Syngelaki, A.; Nicolaides, K.H. Hidden High Rate of Pre-Eclampsia in Twin Compared with Singleton Pregnancy. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 2017, 50, 88–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizzo, G.; Pietrolucci, M.E.; Aiello, E.; Capponi, A.; Arduini, D. Uterine Artery Doppler Evaluation in Twin Pregnancies at 11 + 0 to 13 + 6 Weeks of Gestation. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 2014, 44, 557–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siegler, Y.; Justman, N.; Bachar, G.; Farago, N.; Vitner, D.; Weiner, Z.; Beloosesky, R. Preeclampsia Twin Pregnancies: Time Differ. Approaches? Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2025, 313, 114578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Day, M.C.; Barton, J.R.; O’Brien, J.M.; Istwan, N.B.; Sibai, B.M. The Effect of Fetal Number on the Development of Hypertensive Conditions of Pregnancy. Obstet. Gynecol. 2005, 106, 927–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Task Force on Hypertension in Pregnancy Hypertension in Pregnancy. Report of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists’ Task Force on Hypertension in Pregnancy. Obstet. Gynecol. 2013, 122, 1122–1131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Homer, C.S.E.; Brown, M.A.; Mangos, G.; Davis, G.K. Non-Proteinuric Pre-Eclampsia: A Novel Risk Indicator in Women with Gestational Hypertension. J. Hypertens. 2008, 26, 295–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phipps, E.A.; Thadhani, R.; Benzing, T.; Karumanchi, S.A. Pre-Eclampsia: Pathogenesis, Novel Diagnostics and Therapies. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 2019, 15, 275–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lloyd-Davies, C.; Collins, S.L.; Burton, G.J. Understanding the Uterine Artery Doppler Waveform and Its Relationship to Spiral Artery Remodelling. Placenta 2021, 105, 78–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Ganzo Suárez, T.; de Paco Matallana, C.; Plasencia, W. Spiral, Uterine Artery Doppler and Placental Ultrasound in Relation to Preeclampsia. Best Pr. Res. Clin. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2024, 92, 102426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petla, L.T.; Chikkala, R.; Ratnakar, K.S.; Kodati, V.; Sritharan, V. Biomarkers for the Management of Pre-Eclampsia in Pregnant Women. Indian. J. Med. Res. 2013, 138, 60–67. [Google Scholar]

- Hod, T.; Cerdeira, A.S.; Karumanchi, S.A. Molecular Mechanisms of Preeclampsia. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 2015, 5, a023473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maynard, S.E.; Karumanchi, S.A. Angiogenic Factors and Preeclampsia. Semin. Nephrol. 2011, 31, 33–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, I.; Karumanchi, S.A. Preeclampsia and the Anti-Angiogenic State. Pregnancy Hypertens. 2011, 1, 17–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, A.; Rana, S.; Karumanchi, S.A. Preeclampsia: The Role of Angiogenic Factors in Its Pathogenesis. Physiology 2009, 24, 147–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plasencia, W.; Maiz, N.; Bonino, S.; Kaihura, C.; Nicolaides, K.H. Uterine Artery Doppler at 11 + 0 to 13 + 6 Weeks in the Prediction of Pre-Eclampsia. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 2007, 30, 742–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papageorghiou, A.T.; Yu, C.K.; Bindra, R.; Pandis, G.; Nicolaides, K.H. Fetal Medicine Foundation Second Trimester Screening Group Multicenter Screening for Pre-Eclampsia and Fetal Growth Restriction by Transvaginal Uterine Artery Doppler at 23 Weeks of Gestation. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 2001, 18, 441–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Yue, C. Abnormal Uterine Artery Doppler Ultrasound during Gestational 21-23 Weeks Associated with Pre-Eclampsia. Int. J. Gynaecol. Obstet. 2023, 161, 264–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abonyi, E.O.; Idigo, F.U.; Anakwue, A.-M.C.; Agbo, J.A. Sensitivity of Uterine Artery Doppler Pulsatility Index in Screening for Adverse Pregnancy Outcome in First and Second Trimesters. J. Ultrasound 2023, 26, 517–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonacina, E.; Del Barco, E.; Farràs, A.; Dalmau, M.; Garcia, E.; Gleeson-Vallbona, L.; Serrano, B.; Armengol-Alsina, M.; Catalan, S.; Hernadez, A.; et al. Role of Routine Uterine Artery Doppler at 18–22 and 24–28 Weeks’ Gestation Following Routine First-Trimester Screening for Pre-Eclampsia. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 2025, 65, 63–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, S.L.; Aviram, A.; Porto, L.; Huang, T.; Satkunaratnam, A.; Barrett, J.F.R.; Melamed, N.; Mei-Dan, E. Uterine Artery Doppler to Predict Growth Restriction in Cases of Abnormal First Trimester Analytes. Placenta 2021, 106, 22–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekanem, E.; Karouni, F.; Katsanevakis, E.; Kapaya, H. Implementation of Uterine Artery Doppler Scanning: Improving the Care of Women and Babies High Risk for Fetal Growth Restriction. J. Pregnancy 2023, 2023, 1506447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francisco, C.; Wright, D.; Benkő, Z.; Syngelaki, A.; Nicolaides, K.H. Competing-Risks Model in Screening for Pre-Eclampsia in Twin Pregnancy According to Maternal Factors and Biomarkers at 11–13 Weeks’ Gestation. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 2017, 50, 589–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filipecka-Tyczka, D.; Pokropek, A.; Kajdy, A.; Modzelewski, J.; Rabijewski, M. Uterine Artery Doppler Reference Ranges in a Twin Caucasian Population Followed Longitudinally From 17 to 37 Weeks Gestation Compared to That of Singletons. J. Ultrasound Med. 2021, 40, 2421–2429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Queirós, A.; Domingues, S.; Gomes, L.; Pereira, I.; Brito, M.; Cohen, Á.; Alves, M.; Papoila, A.L.; Simões, T. First-Trimester Uterine Artery Doppler and Hypertensive Disorders in Twin Pregnancies: Use of Twin versus Singleton References. Int. J. Gynaecol. Obstet. 2024, 167, 705–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, L.; He, B.; Zhou, Y.; Chen, T.; Gao, Y.; Yao, B. Utility of Uterine Artery Doppler Ultrasound Imaging in Predicting Preeclampsia during Pregnancy: A Meta-Analysis. Med. Ultrason. 2024, 26, 197–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geipel, A.; Berg, C.; Germer, U.; Katalinic, A.; Krapp, M.; Smrcek, J.; Gembruch, U. Doppler Assessment of the Uterine Circulation in the Second Trimester in Twin Pregnancies: Prediction of Pre-Eclampsia, Fetal Growth Restriction and Birth Weight Discordance. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 2002, 20, 541–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, C.K.H.; Papageorghiou, A.T.; Boli, A.; Cacho, A.M.; Nicolaides, K.H. Screening for Pre-Eclampsia and Fetal Growth Restriction in Twin Pregnancies at 23 Weeks of Gestation by Transvaginal Uterine Artery Doppler. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 2002, 20, 535–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pilalis, A.; Souka, A.P.; Antsaklis, P.; Daskalakis, G.; Papantoniou, N.; Mesogitis, S.; Antsaklis, A. Screening for Pre-Eclampsia and Fetal Growth Restriction by Uterine Artery Doppler and PAPP-A at 11-14 Weeks’ Gestation. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 2007, 29, 135–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velauthar, L.; Plana, M.N.; Kalidindi, M.; Zamora, J.; Thilaganathan, B.; Illanes, S.E.; Khan, K.S.; Aquilina, J.; Thangaratinam, S. First-Trimester Uterine Artery Doppler and Adverse Pregnancy Outcome: A Meta-Analysis Involving 55,974 Women. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 2014, 43, 500–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, C.K.H.; Khouri, O.; Onwudiwe, N.; Spiliopoulos, Y.; Nicolaides, K.H. Fetal Medicine Foundation Second-Trimester Screening Group Prediction of Pre-Eclampsia by Uterine Artery Doppler Imaging: Relationship to Gestational Age at Delivery and Small-for-Gestational Age. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 2008, 31, 310–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lees, C.; Parra, M.; Missfelder-Lobos, H.; Morgans, A.; Fletcher, O.; Nicolaides, K.H. Individualized Risk Assessment for Adverse Pregnancy Outcome by Uterine Artery Doppler at 23 Weeks. Obstet. Gynecol. 2001, 98, 369–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, A.M.; Bindra, R.; Curcio, P.; Cicero, S.; Nicolaides, K.H. Screening for Pre-Eclampsia and Fetal Growth Restriction by Uterine Artery Doppler at 11–14 Weeks of Gestation. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 2001, 18, 583–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedroso, M.A.; Palmer, K.R.; Hodges, R.J.; Costa, F.D.S.; Rolnik, D.L. Uterine Artery Doppler in Screening for Preeclampsia and Fetal Growth Restriction. Rev. Bras. Ginecol. Obstet. 2018, 40, 287–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geipel, A.; Hennemann, F.; Fimmers, R.; Willruth, A.; Lato, K.; Gembruch, U.; Berg, C. Reference Ranges for Doppler Assessment of Uterine Artery Resistance and Pulsatility Indices in Dichorionic Twin Pregnancies. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 2011, 37, 663–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Springer, S.; Polterauer, M.; Stammler-Safar, M.; Zeisler, H.; Leipold, H.; Worda, C.; Worda, K. Notching and Pulsatility Index of the Uterine Arteries and Preeclampsia in Twin Pregnancies. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 2653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, K.; Mailath-Pokorny, M.; Elhenicky, M.; Schmid, M.; Zeisler, H.; Worda, C. Mean, Lowest, and Highest Pulsatility Index of the Uterine Artery and Adverse Pregnancy Outcome in Twin Pregnancies. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2011, 205, 549.e1–549.e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizzo, G.; Arduini, D.; Romanini, C. Uterine Artery Doppler Velocity Waveforms in Twin Pregnancies. Obstet. Gynecol. 1993, 82, 978–983. [Google Scholar]

- Svirsky, R.; Yagel, S.; Ben-Ami, I.; Cuckle, H.; Klug, E.; Maymon, R. First Trimester Markers of Preeclampsia in Twins: Maternal Mean Arterial Pressure and Uterine Artery Doppler Pulsatility Index. Prenat. Diagn. 2014, 34, 956–960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, A.E.G.M.T.; Mauad Filho, F.; Abreu, P.S.G.; Mauad, F.M.; Araujo Júnior, E.; Martins, W.P. Reproducibility of First- and Second-Trimester Uterine Artery Pulsatility Index Measured by Transvaginal and Transabdominal Ultrasound. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 2015, 46, 546–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez, O.; Figueras, F.; Fernández, S.; Bennasar, M.; Martínez, J.M.; Puerto, B.; Gratacós, E. Reference Ranges for Uterine Artery Mean Pulsatility Index at 11–41 Weeks of Gestation. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 2008, 32, 128–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francisco, C.; Gamito, M.; Reddy, M.; Rolnik, D.L. Screening for Preeclampsia in Twin Pregnancies. Best. Pr. Res. Clin. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2022, 84, 55–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Zhao, D.; Liu, Y.; Zhou, J.; Zou, G.; Zhang, Y.; Guo, M.; Duan, T.; Van Mieghem, T.; Sun, L. Screening for Preeclampsia in Low-Risk Twin Pregnancies at Early Gestation. Acta Obstet. Gynecol. Scand. 2020, 99, 1346–1353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benkő, Z.; Chaveeva, P.; de Paco Matallana, C.; Zingler, E.; Wright, D.; Nicolaides, K.H. Revised Competing-Risks Model in Screening for Pre-Eclampsia in Twin Pregnancy by Maternal Characteristics and Medical History. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 2019, 54, 617–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maymon, R.; Trahtenherts, A.; Svirsky, R.; Melcer, Y.; Madar-Shapiro, L.; Klog, E.; Meiri, H.; Cuckle, H. Developing a New Algorithm for First and Second Trimester Preeclampsia Screening in Twin Pregnancies. Hypertens. Pregnancy 2017, 36, 108–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergeron, T.S.; Roberge, S.; Carpentier, C.; Sibai, B.; McCaw-Binns, A.; Bujold, E. Prevention of Preeclampsia with Aspirin in Multiple Gestations: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Am. J. Perinatol. 2016, 33, 605–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).