Dural Tear and Cerebrospinal Fluid Leakage in Anterior Cervical Spine Surgery: Pathophysiology, Management, and Evolving Repair Techniques

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Epidemiology and Risk Factors

2.1. Incidence Across Surgical Contexts

2.2. Influence of Surgical Approach

2.3. Patient-Related Risk Factors

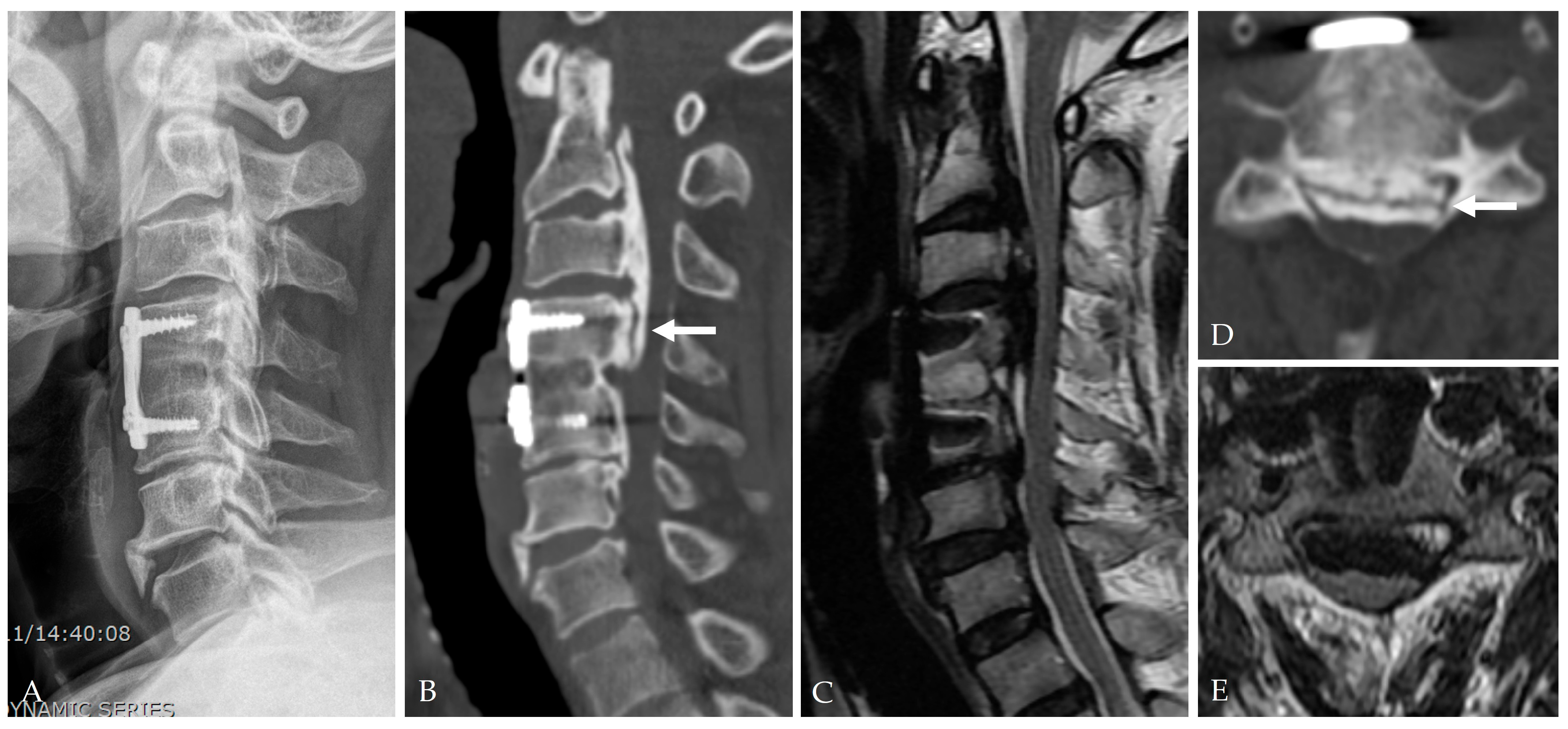

2.4. Radiologic Predictors and Morphological Correlates

- Broad-based or continuous/mixed-type OPLL: Confers approximately 10-fold higher risk of DT than segmental types [37].

2.5. Disease-Specific Factors: Dural Ossification and Adhesion Severity

2.6. Intraoperative Technical Factors

2.7. Clinical Consequences and Prognostic Significance

2.8. Summary

3. Pathophysiology of Dural Tear and Cerebrospinal Fluid Leakage

3.1. Microstructural and Cellular Alterations of the PLL–Dura Interface

3.2. Biomechanical Transformation of the Ossified Interface

3.3. Role of Dural Ossification (DO) in Leak Formation

3.4. CSF Pressure Dynamics and Enlargement of Microdefects

3.5. Inflammatory and Biochemical Factors

3.6. Arachnoid Integrity as a Determinant of Leak Severity

3.7. Secondary Sequelae and Systemic Consequences

3.8. Summary of Pathophysiology of Dural Tear and Cerebrospinal Fluid Leakage

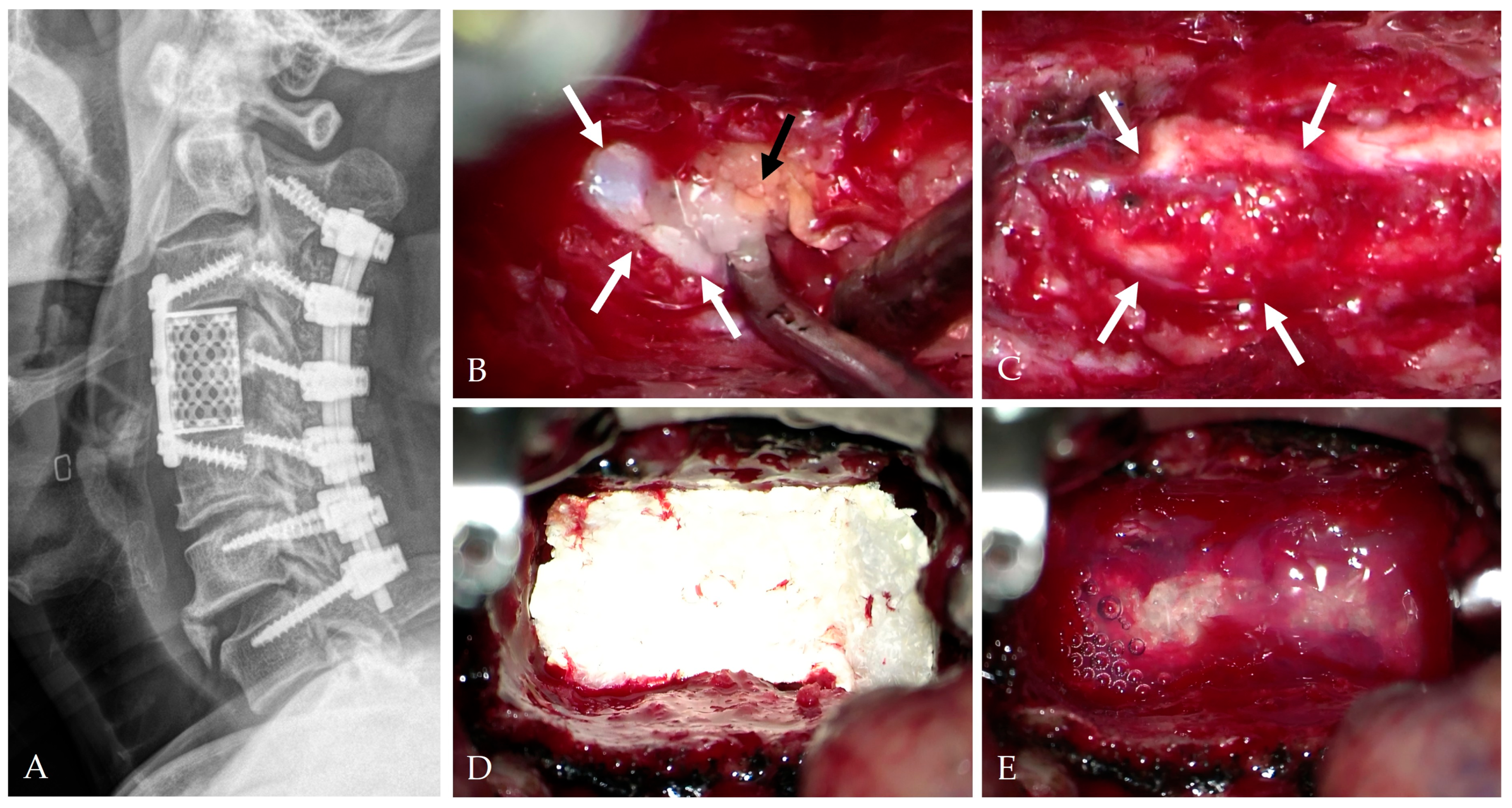

4. Intraoperative Repair Technique

4.1. Classification and Principles of Repair

4.2. Floating Repair and Dura-Preserving Techniques

4.3. Autologous Grafts and Biological Reinforcement

4.4. Artificial Dural Substitutes

4.5. Sealants and Adhesives

4.6. Composite “Sandwich” Repair

4.7. Controlled CSF Diversion

4.8. Vascularized Flap Reinforcement

4.9. Summary of Intraoperative Repair Technique

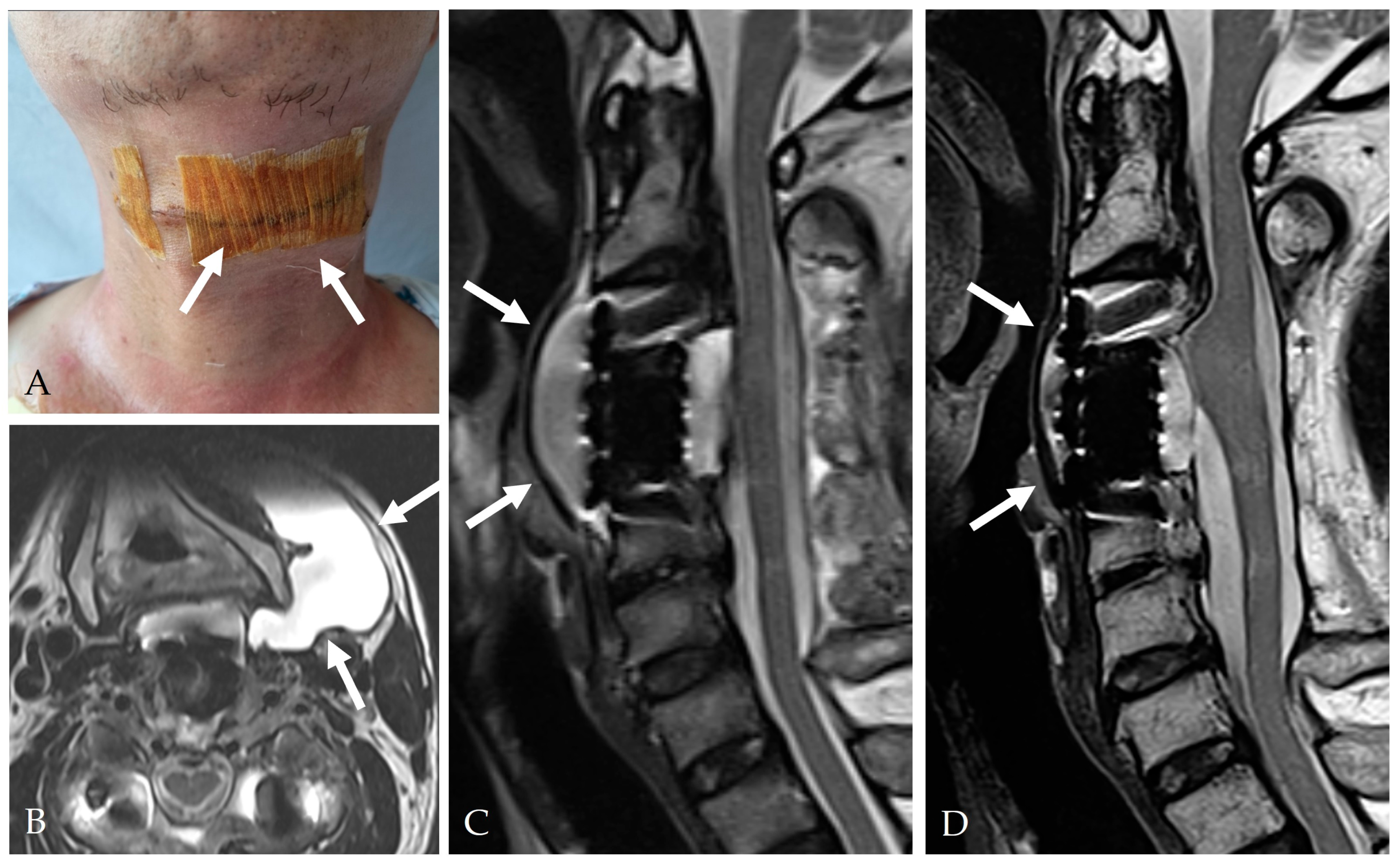

5. Postoperative Management and Outcomes

5.1. CSF Pressure Regulation

5.2. Positioning and Mobilization

5.3. Wound Care and Infection Prevention

5.4. Pseudomeningocele Management

- <2 cm → observation

- 2–4 cm → aspiration and compression

5.5. Adjunctive Therapies

5.6. Functional Outcomes

6. Complications and Reoperation

6.1. Early Local Complications

6.2. Infectious Complications

6.3. Intracranial Hypotension and Remote Cerebral Hemorrhage

6.4. Mechanical/Implant-Related Complications

6.5. Pseudomeningocele and Late Recurrence

6.6. Reoperation Rates and Predictors

- DT occurrence (OR 4.97)

- Kyphosis or loss of lordosis < 10°

- Hardware failure (OR 192.09) [27]

6.7. Summary of Complications and Reoperation

7. Future Directions and Technological Innovations

7.1. Overview

7.2. Bioactive Hydrogels

7.3. 3D-Printed Bioresorbable Scaffolds

7.4. Regenerative Medicine and Stem Cells

7.5. Nanotechnology and Biosensing Dura

7.6. Artificial Intelligence (AI)

7.7. Standardization and Research Needs

7.8. Summary of Future Directions and Technological Innovations

8. Limitations

9. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| DT | Dural Tear |

| CSF | Cerebrospinal Fluid |

| OPLL | Ossification of Posterior Longitudinal Ligament |

| ACDF | Anterior Cervical Discectomy and Fusion |

| ACCF | Anterior Cervical Corpectomy and Fusion |

| PEG | Polyethylene Glycol |

| PRVCLD | Pump-Regulated Volumetric Continuous Lumbar Drainage |

| DO | Dural Ossification |

| MRI | Magnetic Resonance Imaging |

| CT | Computed Tomography |

| PGA | Polyglycolic Acid |

| SCM | Sternocleidomastoid |

| PCL | Polycaprolactate |

| EBP | Epidural Blood Patch |

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

References

- Mazur, M.; Jost, G.A.; Schmidt, M.H.; Bisson, E.F. management of cerebrospinal fluid leaks after anterior decompression for ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament: A review of the literature. Neurosurg. Focus 2011, 30, E13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mizuno, J.; Nakagawa, H.; Song, J.; Matsuo, N. Surgery for dural ossification in association with cervical ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament via an anterior approach. Neurol. India 2005, 53, 354–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oshima, Y.; Nakamoto, H.; Doi, T.; Miyahara, J.; Sato, Y.; Tonosu, J.; Tachibana, N.; Urayama, D.; Saiki, F.; Anno, M.; et al. Impact of incidental dural tears on postoperative outcomes in patients undergoing cervical spine surgery: A multicenter retrospective cohort study. Spine J. 2025, 25, 91–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos, M.R.D.; Liu, G.; Tan, J.H.; Tan, J.H.J.; Ruiz, J.N.M.; Hey, H.W.D.; Lau, L.L.; Kumar, N.; Thambiah, J.; Wong, H.K. Risk factors for surgical complications in the management of ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament. Spine J. 2021, 21, 1176–1184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fujiyoshi, T.; Yamazaki, M.; Kawabe, J.; Endo, T.; Furuya, T.; Koda, M.; Okawa, A.; Takahashi, K.; Konishi, H. A new concept for making decisions regarding the surgical approach for cervical ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament: The K-line. Spine 2008, 33, E990–E993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odate, S.; Shikata, J.; Soeda, T.; Yamamura, S.; Kawaguchi, S. Surgical results and complications of anterior decompression and fusion as a revision surgery after initial posterior surgery for cervical myelopathy due to ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament. J. Neurosurg. Spine 2017, 26, 466–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tetreault, L.; Nakashima, H.; Kato, S.; Kryshtalskyj, M.; Nagoshi, N.; Nouri, A.; Singh, A.; Fehlings, M.G. A Systematic Review of Classification Systems for Cervical Ossification of the Posterior Longitudinal Ligament. Global Spine J. 2019, 9, 85–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, J.; Yuan, C.; Du, Y.; Jia, S.; Zhang, C.; Liu, Z.; Wang, K.; Duan, W.; Wang, Z.; Wang, X.; et al. Dural ossification associated with ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament in the cervical spine: A retrospective analysis. Eur. Spine J. 2022, 31, 3462–3469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Min, J.H.; Jang, J.S.; Lee, S.H. Clinical significance of the double-layer sign on computed tomography in OPLL. Neurosurgery 2007, 61, 118–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tayal, A.; Pahwa, B.; Garg, K. Reoperation rate and risk factors of reoperation for ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament (OPLL): A systematic review and meta-analysis. Neurosurg. Rev. 2023, 46, 313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, B.D.; Verla, T.; Reddy, D.; Winnegan, L.; Omeis, I. Reliable intraoperative repair nuances of CSF leak in anterior cervical spine surgery. World Neurosurg. 2016, 88, 252–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Yang, L.; Chen, D.; Wang, X.; Lu, X.; Yuan, W. Implications of different patterns of the “double-layer sign” in cervical OPLL. Eur. Spine J. 2015, 24, 1631–1639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Guo, Y.; Chen, D.; Lu, X.; Wang, X.; Tian, H.; Yuan, W. Diagnosis and surgery of OPLL associated with dural ossification in the cervical spine. Eur. Spine J. 2009, 18, 1541–1547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epstein, N.E. Identification of OPLL extending through the dura on preoperative CT of the cervical spine. Spine 2002, 27, 182–186. [Google Scholar]

- Mizuno, J. Radiologic evaluation of ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament with dural ossification. Neurosurg. Clin. N. Am. 2018, 29, 55–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Du, Y.Q.; Cui, G.Q.; Qi, M.Y.; Zhang, B.Y.; Guan, J.; Jian, F.Z.; Duan, W.R.; Chen, Z. A novel CT scoring system for evaluating dural defect risk in anterior OPLL surgery. Clin. Neurol. Neurosurg. 2024, 242, 108315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashimoto, M.; Hirai, T.; Sakai, K.; Yamada, K.; Sakaeda, K.; Hashimoto, J.; Egawa, S.; Morishita, S.; Matsukura, Y.; Inose, H.; et al. Comparison of postoperative complications and outcomes in anterior cervical spine surgery: OPLL versus cervical spondylotic myelopathy. Clin. Spine Surg. 2024, 37, 170–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maxin, A.J.; Pistone, T.S.; Sattur, M.G.; Borg, N. Repair of a ventral cervical CSF leak via single-level ACDF without corpectomy: Illustrative case. J. Neurosurg. Case Lessons 2025, 9, CASE24770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bi, X.; Liu, B.; Mao, Z.; Wang, C.; Dunne, N.; Fan, Y.; Li, X. Materials for dural reconstruction in preclinical and clinical studies: Advantages and drawbacks. Mater. Sci. Eng. C Mater. Biol. Appl. 2020, 117, 111326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epstein, N.E. Wound-peritoneal shunts: Part of the complex management of anterior dural lacerations in OPLL. Surg. Neurol. 2009, 72, 630–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Neill, K.R.; Neuman, B.J.; Peters, C.; Riew, K.D. Risk factors for dural tears in the cervical spine. Spine 2014, 39, E1015–E1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takenaka, S.; Kashii, M.; Iwasaki, M.; Makino, T.; Sakai, Y.; Kaito, T. Risk factor analysis of surgery-related complications in primary cervical spine surgery for degenerative diseases using a surgeon-maintained database. Bone Jt. J. 2021, 103-B, 157–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mizuno, J.; Nakagawa, H.; Matsuo, N.; Song, J. Dural ossification associated with cervical OPLL: Frequency and neuroimaging comparison. J. Neurosurg. Spine 2005, 2, 425–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, T.; Shen, Y.; Wang, L.F.; Cao, J.M.; Ding, W.Y.; Ma, Q.H. Cerebrospinal fluid leakage during anterior cervical spine surgery for severe OPLL: Prevention and treatment. Orthop. Surg. 2012, 4, 247–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmalz, P.; Griessenauer, C.; Ogilvy, C.S.; Thomas, A. Use of an absorbable synthetic polymer dural substitute for repair of dural defects: A technical note. Cureus 2018, 10, e2127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gazzeri, R.; Galarza, M.; Callovini, G. Use of tissue sealant patch (TachoSil) in managing CSF leaks after anterior cervical discectomy and fusion. Br. J. Neurosurg. 2023, 37, 1406–1409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, S.W.; Lee, S.H.; Shin, H.K.; Jeon, S.R.; Roh, S.W.; Park, J.H. Management of CSF leakage by pump-regulated volumetric continuous lumbar drainage following anterior cervical decompression for OPLL. Neurospine 2023, 20, 1421–1430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syre, P.; Bohman, L.E.; Baltuch, G.; Le Roux, P.; Welch, W.C. CSF leaks and their management after anterior cervical discectomy and fusion: A report of 13 cases. Spine 2014, 39, E936–E943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez-Roman, R.J.; Urakov, T. Cervical subarachnoid drain for treatment of CSF leak: 2-dimensional operative video. Oper. Neurosurg. 2021, 21, E439–E440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guerin, P.; El Fegoun, A.B.; Obeid, I.; Gille, O.; Lelong, L.; Luc, S.; Bourghli, A.; Cursolle, J.C.; Pointillart, V.; Vital, J.M. Incidental durotomy during spine surgery: Incidence, management, and complications. Injury 2012, 43, 397–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gandhi, J.; DiMatteo, A.; Joshi, G.; Smith, N.L.; Khan, S.A. CSF leaks secondary to dural tears: Etiology, clinical evaluation, and management. Int. J. Neurosci. 2021, 131, 689–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moon, J.H.; Lee, S.; Chung, C.K.; Kim, C.H.; Heo, W. How to address cerebrospinal fluid leakage following ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament surgery. J. Clin. Neurosci. 2017, 45, 172–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koda, M.; Mochizuki, M.; Konishi, H.; Aiba, A.; Kadota, R.; Inada, T.; Kamiya, K.; Ota, M.; Maki, S.; Takahashi, K.; et al. Comparison of outcomes between laminoplasty, posterior fusion, and anterior decompression for K-line (-) cervical OPLL. Eur. Spine J. 2016, 25, 2294–2301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshihara, H.; Yoneoka, D. Incidental dural tear in cervical spine surgery: Analysis of a nationwide database. J. Spinal Disord. Tech. 2015, 28, 19–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarkar, S.; Nair, B.R.; Rajshekhar, V. Complications following central corpectomy in 468 consecutive patients with degenerative cervical disease. Neurosurg. Focus 2016, 40, E10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapadia, B.H.; Decker, S.I.; Boylan, M.R.; Shah, N.V.; Paulino, C.B. Risk factors for CSF leak following ACDF. Clin. Spine Surg. 2019, 32, E86–E90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halayqeh, S.; Glueck, J.; Balmaceno-Criss, M.; Alsoof, D.; McDonald, C.L.; Diebo, B.G.; Daniels, A.H. Delayed CSF leak following anterior cervical discectomy and fusion. N. Am. Spine Soc. J. 2023, 16, 100271. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Durand, W.M.; DePasse, J.M.; Kuris, E.O.; Yang, J.; Daniels, A.H. Late-presenting dural tear: Incidence, risk factors, and associated complications. Spine J. 2018, 18, 2043–2050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lien, J.R.; Patel, R.D.; Graziano, G.P. Sternocleidomastoid muscular flap for persistent CSF leak after anterior cervical spine surgery. J. Spinal Disord. Tech. 2013, 26, 449–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narotam, P.K.; José, S.; Nathoo, N.; Taylon, C.; Vora, Y. Collagen matrix (DuraGen) in dural repair: Analysis of a new modified technique. Spine 2004, 29, 2861–2867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.Y.; Oh, B.H.; Kim, I.S.; Hong, J.T.; Sung, J.H.; Lee, H.J. Safety and effectiveness of lumbar drainage for CSF leakage after spinal surgery. Neurochirurgie 2023, 69, 101501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhai, J.; Panchal, R.R.; Tian, Y.; Wang, S.; Zhao, L. Management of CSF leak after anterior cervical decompression surgery. Orthopedics 2018, 41, e283–e288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, R.P.; Zhang, Q.; Yang, L.L.; Cheng, X.L.; Zhao, J.W. Clinical management of dural defects: A review. World J. Clin. Cases 2023, 11, 2903–2915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrew, S.A.; Sidhu, K.S. Cervical-peritoneal shunt placement for postoperative cervical pseudomeningocele. J. Spinal Disord. Tech. 2005, 18, 290–292. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Elder, B.D.; Theodros, D.; Sankey, E.W.; Bydon, M.; Goodwin, C.R.; Wolinsky, J.P.; Sciubba, D.M.; Gokaslan, Z.L.; Bydon, A.; Witham, T.F. Management of CSF leakage during ACDF and its effect on fusion. World Neurosurg. 2016, 89, 636–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joseph, V.; Kumar, G.S.; Rajshekhar, V. Cerebrospinal fluid leak during cervical corpectomy for ossified posterior longitudinal ligament: Incidence, management, and outcome. Spine 2009, 34, 491–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoshida, H.; Takai, K.; Taniguchi, M. Leakage detection on CT myelography for targeted epidural blood patch in spontaneous cerebrospinal fluid leaks: Calcified or ossified spinal lesions ventral to the thecal sac. J. Neurosurg. Spine 2014, 21, 432–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugrue, P.A.; McClendon, J., Jr.; Halpin, R.J.; Liu, J.C.; Koski, T.R.; Ganju, A. Surgical management of cervical ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament: Natural history and the role of surgical decompression and stabilization. Neurosurg. Focus 2011, 30, E3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Black, P. Cerebrospinal fluid leaks following spinal surgery: Use of fat grafts for prevention and repair. Technical note. Neurosurg. Focus 2000, 9, e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balasubramaniam, C.; Rao, S.M.; Subramaniam, K. Management of CSF leak following spinal surgery. Childs Nerv. Syst. 2014, 30, 1543–1547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Z.; Tian, R.; Jia, Y.T.; Xu, T.T.; Liu, Y. Treatment of cerebrospinal fluid leak after spine surgery. Chin. J. Traumatol. 2017, 20, 81–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hyun, S.J.; Rhim, S.C.; Ra, Y.S. Repair of a cerebrospinal fluid fistula using a muscle pedicle flap: Technical case report. Neurosurgery 2009, 65, E1214–E1215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phan, A.; Shah, S.; Joo, P.; Mesfin, A. Can cervical and lumbar epidural blood patches help avoid revision surgery for postoperative dural tears? World Neurosurg. 2022, 164, e877–e883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Category | Key Findings |

|---|---|

| Procedure Type | Routine ACDF/ACCF: very low incidence (<0.5%) |

| Pathology | OPLL with dural ossification: 4–32% (up to 63%) |

| Surgical Approach | Anterior: 31% vs. Posterior: 9.3% (OR 1.9) |

| Patient Factors | Older age (>65), obesity (BMI ≥ 30), steroid use, revision surgery |

| Radiological Predictors | Double-layer and hook signs, K-line negativity, OPLL occupying ratio ≥ 60% |

| Mechanism | Description |

|---|---|

| Cellular Metaplasia | Fibroblast at the PLL–dura junction differentiates into osteogenic cells expressing BMP-2, Runx2, and VEGF |

| Loss of Elasticity | Collagen disorganization and fragmentation of elastic fibers reduce tensile strength |

| Biomechanical Stress | Shear strain at ossified junctions exceeds 15%, directly tearing fragile dura |

| CSF Pressure Effect | Pulsatile CSF waves expand microtears into larger defects, forming a pseudomeningocele |

| Inflammatory Cascade | TNF-α and IL-1β increase vascular permeability and degrade ECM, delaying closure |

| Defect Size | Recommended Strategy | Materials/Adjuncts | Reported Success |

|---|---|---|---|

| Small (<5 mm) | Gelatin sponge with short-term lumbar drainage | Gelfoam®, fibrin glue | 90–95% |

| Moderate (5–10 mm) | Fascia or pericardium onlay reinforced with fibrin or PEG hydrogel | Tisseel®, Duraseal® | >95% |

| Large (>10 mm) | Composite “sandwich” repair using artificial dura + sealant + fat graft | DuraGen®, TachoSil® | >95% |

| Complex/Recurrent | Vascularized flap + PRVCLD system | SCM or pectoralis flap | 100% |

| Management Step | Key Practice | Clinical Outcome/Evidence |

|---|---|---|

| Pressure Regulation | Pump-regulated lumbar drainage (PRVCLD): 6–8 cm H2O, 5–10 mL/h for 3–5 days | 90% leak resolution |

| Mobilization | Early ambulation after drainage < 30 mL/day (48–72 h) | Improved comfort, fewer pulmonary issues |

| Pseudomeningocele | Observation (<2 cm); aspiration or graft for >4 cm lesions | 90% spontaneous resolution |

| Reoperation Rate | Persistent leak/implant failure/OPLL progression | ~5% overall |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yang, J.J.; Park, J.; Park, J.-B.; Kim, S. Dural Tear and Cerebrospinal Fluid Leakage in Anterior Cervical Spine Surgery: Pathophysiology, Management, and Evolving Repair Techniques. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 8478. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238478

Yang JJ, Park J, Park J-B, Kim S. Dural Tear and Cerebrospinal Fluid Leakage in Anterior Cervical Spine Surgery: Pathophysiology, Management, and Evolving Repair Techniques. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(23):8478. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238478

Chicago/Turabian StyleYang, Jae Jun, Jiwon Park, Jong-Beom Park, and Suo Kim. 2025. "Dural Tear and Cerebrospinal Fluid Leakage in Anterior Cervical Spine Surgery: Pathophysiology, Management, and Evolving Repair Techniques" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 23: 8478. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238478

APA StyleYang, J. J., Park, J., Park, J.-B., & Kim, S. (2025). Dural Tear and Cerebrospinal Fluid Leakage in Anterior Cervical Spine Surgery: Pathophysiology, Management, and Evolving Repair Techniques. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(23), 8478. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238478