Influence of Prostate Volume on Targeted Biopsy Outcomes and PI-RADS Predictive Value for Significant Prostate Cancer

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Patients and Methods

2.2. Statistical Analysis

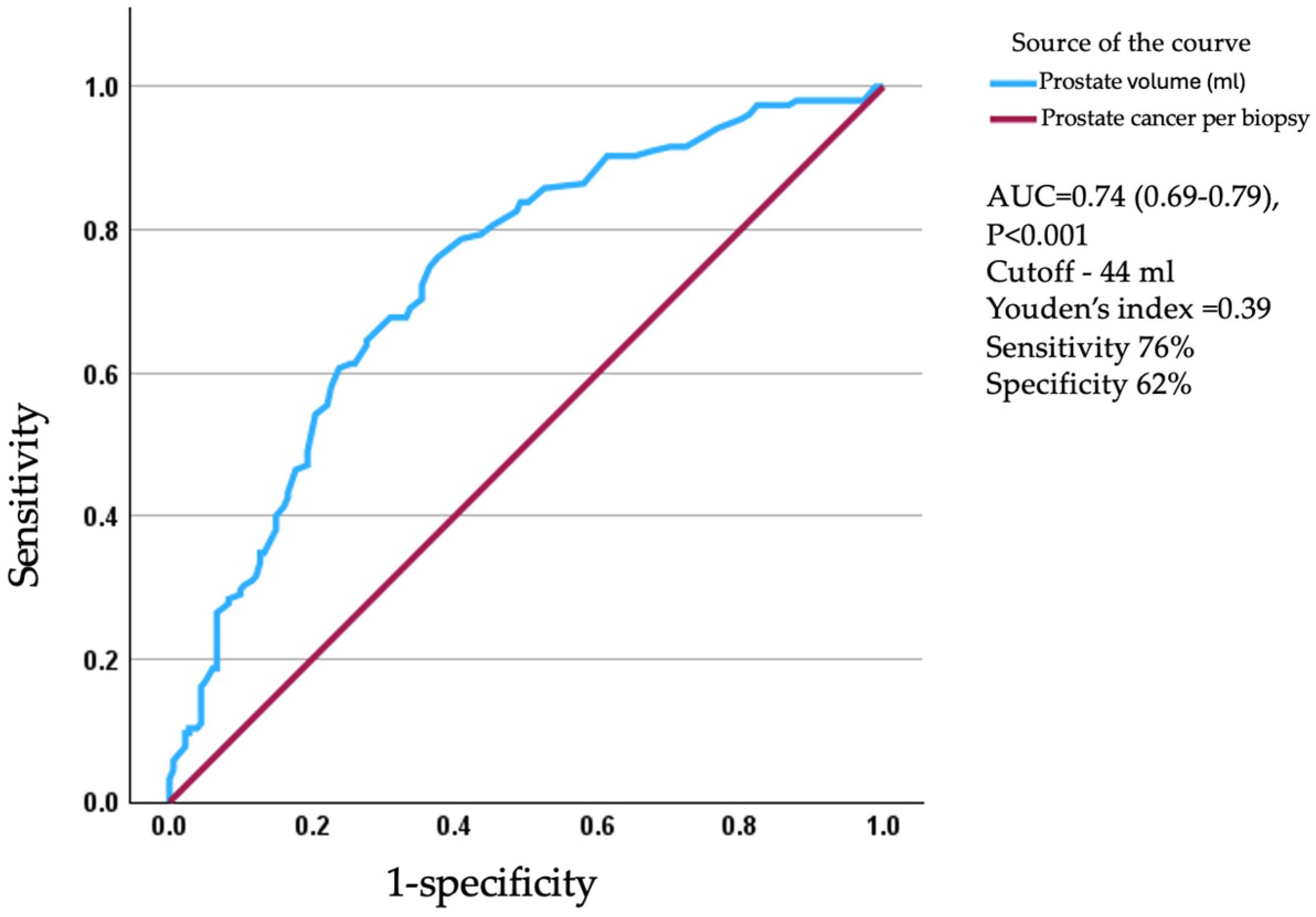

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PI-RADS | Prostate Imaging Reporting and Data System |

| CSPC | Clinically Significant Prostate Cancer |

| HRPC | High Risk Prostate Cancer |

| ROI | Region of Interest |

| DRE | Digital Rectal Examination |

| PSA | Prostate Specific Antigen |

| ISUP | International Society of Urological Pathology |

References

- Fink, K.G.; Hutarew, G.; Pytel, A.; Esterbauer, B.; Jungwirth, A.; Dietze, O.; Schmeller, N. One 10-core prostate biopsy is superior to two sets of sextant prostate biopsies. BJU Int. 2003, 92, 385–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, W.; Davis, N.F.; Elamin, S.; Ahern, P.; Brady, C.M.; Sweeney, P. Six-core versus twelve-core prostate biopsy: A retrospective study comparing accuracy, oncological outcomes and safety. Ir. J. Med. Sci. 2016, 185, 219–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delongchamps, N.B.; De La Roza, G.; Jones, R.; Jumbelic, M.; Haas, G.P. Saturation biopsies on autopsied prostates for detecting and characterizing prostate cancer. BJU Int. 2009, 103, 49–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kasivisvanathan, V.; Stabile, A.; Neves, J.B.; Giganti, F.; Valerio, M.; Shanmugabavan, Y.; Clement, K.D.; Sarkar, D.; Philippou, Y.; Thurtle, D.; et al. Magnetic Resonance Imaging-targeted Biopsy Versus Systematic Biopsy in the Detection of Prostate Cancer: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis(Figure presented.). Eur. Urol. 2019, 76, 284–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Furlan, A.; Borhani, A.A.; Westphalen, A.C. Multiparametric MR imaging of the Prostate: Interpretation Including Prostate Imaging Reporting and Data System Version 2. Urol. Clin. N. Am. 2018, 45, 439–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Christidis, D.; McGrath, S.; Leaney, B.; O’Sullivan, R.; Lawrentschuk, N. Interpreting Prostate Multiparametric Magnetic Resonance Imaging: Urologists’ Guide Including Prostate Imaging Reporting and Data System. Urology 2018, 111, 136–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, J.E.; Van Leeuwen, P.J.; Moses, D.; Shnier, R.; Brenner, P.; Delprado, W.; Pulbrook, M.; Böhm, M.; Haynes, A.; Hayen, A.; et al. The diagnostic performance of multiparametric magnetic resonance imaging to detect significant prostate cancer. J. Urol. 2016, 195, 1428–1435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bjurlin, M.A.; Meng, X.; Le Nobin, J.; Wysock, J.S.; Lepor, H.; Rosenkrantz, A.B.; Taneja, S.S. Optimization of prostate biopsy: The role of magnetic resonance imaging targeted biopsy in detection, localization and risk assessment. J. Urol. 2014, 192, 648–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasivisvanathan, V.; Rannikko, A.S.; Borghi, M.; Panebianco, V.; Mynderse, L.A.; Vaarala, M.H.; Briganti, A.; Budäus, L.; Hellawell, G.; Hindley, R.G.; et al. MRI-Targeted or Standard Biopsy for Prostate-Cancer Diagnosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2018, 378, 1767–1777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leibovici, D.; Shilo, Y.; Raz, O.; Stav, K.; Sandbank, J.; Segal, M.; Zisman, A. Is the diagnostic yield of prostate needle biopsies affected by prostate volume? Urol. Oncol. Semin. Orig. Investig. 2013, 31, 1003–1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hong, S.K.; Poon, B.Y.; Sjoberg, D.D.; Scardino, P.T.; Eastham, J.A. Prostate size and adverse pathologic features in men undergoing radical prostatectomy. Urology 2014, 84, 153–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newton, M.R.; Phillips, S.; Chang, S.S.; Clark, P.E.; Cookson, M.S.; Davis, R.; Fowke, J.H.; Herrell, S.D.; Baumgartner, R.; Chan, R.; et al. Smaller prostate size predicts high grade prostate cancer at final pathology. J. Urol. 2010, 184, 930–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Briganti, A.; Chun, F.K.H.; Suardi, N.; Gallina, A.; Walz, J.; Graefen, M.; Shariat, S.; Ebersdobler, A.; Rigatti, P.; Perrotte, P.; et al. Prostate volume and adverse prostate cancer features: Fact not artifact. Eur. J. Cancer 2007, 43, 2669–2677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freedland, S.J.; Isaacs, W.B.; Platz, E.A.; Terris, M.K.; Aronson, W.J.; Amling, C.L.; Presti, J.C.; Kane, C.J. Prostate size and risk of high-grade, advanced prostate cancer and biochemical progression after radical prostatectomy: A search database study. J. Clin. Oncol. 2005, 23, 7546–7554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.J.; Brooks, J.D.; Ferrari, M.; Nolley, R.; Presti, J.C. Small prostate size and high grade disease-biology or artifact? J. Urol. 2011, 185, 2108–2111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandhu, S.; Moore, C.M.; Chiong, E.; Beltran, H.; Bristow, R.G.; Williams, S.G. Prostate cancer. Lancet 2021, 398, 1075–1090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaid, D.J. The complex genetic epidemiology of prostate cancer. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2004, 13, R103–R121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walsh, P.C.; Partin, A.W. Family History Facilitates the Early Diagnosis of Prostate Carcinoma. Cancer 1997, 80, 1871–1874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benson, M.C.; Ihn Seong Whang Pantuck, A.; Ring, K.; Kaplan, S.A.; Olsson, C.A.; Cooner, W.H. Prostate specific antigen density: A means of distinguishing benign prostatic hypertrophy and prostate cancer. J. Urol. 1992, 147, 815–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, I.M.; Pauler, D.K.; Goodman, P.J.; Tangen, C.M.; Scott Lucia, M.; Parnes, H.L.; Minasian, L.M.; Ford, L.G.; Lippman, S.M.; Crawford, E.D. Prevalence of Prostate Cancer among Men with a Prostate-Specific Antigen Level ≤4.0 ng per Milliliter. N. Engl. J. Med. 2004, 350, 2239–2246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bangma, C.H.; Rietbergen, J.B.W.; Kranse, R.; Blijenberg, B.G.; Petterson, K.; Schroder, F.H. The free-to-total prostate specific antigen ratio improves the specificity of prostate specific antigen in screening for prostate cancer in the general population. J. Urol. 1997, 157, 2191–2196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uzzo, R.G.; Wei, J.T.; Waldbaum, R.S.; Perlmutter, A.I.; Byrne, J.C.; Darracott Vaughan, E. The influence of prostate size on cancer detection. Urology 1995, 46, 831–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Azab, R.; Toi, A.; Lockwood, G.; Kulkarni, G.S.; Fleshner, N. Prostate Volume Is Strongest Predictor of Cancer Diagnosis at Transrectal Ultrasound-Guided Prostate Biopsy with Prostate-Specific Antigen Values Between 2.0 and 9.0 ng/mL. Urology 2007, 69, 103–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karakiewicz, P.I.; Bazinet, M.; Aprikian, A.G.; Trudel, C.; Aronson, S.; Nachabe, M.; Péloquint, F.; Dessureault, J.; Goyal, M.S.; Bégin, L.R.; et al. Outcome of sextant biopsy according to gland volume. Urology 1997, 49, 55–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Khalil, S.; Ibilibor, C.; Cammack, J.T.; de Riese, W. Association of prostate volume with incidence and aggressiveness of prostate cancer. Res. Rep. Urol. 2016, 8, 201–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yilmaz, H.; Ustuner, M.; Ciftci, S.; Yavuz, U.; Ozkan, T.A.; Dillioglugil, O. Prostate volume predicts high grade prostate cancer both in digital rectal examination negative (ct1c) and positive (≥ct2) patients. Int. Braz J. Urol. 2014, 40, 613–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aloufi, W.D.; Al Mopti, A.; Al-Tawil, A.; Huang, Z.; Nabi, G. Identifying Optimal Prostate Biopsy Strategy for the Detection Rate of Clinically Significant Prostate Cancer: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomised Controlled Trials (RCTs) in Biopsy-Naïve Population. Cancers 2025, 17, 458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moolupuri, A.; Camacho, J.; de Riese, W.T. Association between prostate size and the incidence of prostate cancer: A meta-analysis and review for urologists and clinicians. Int. Urol. Nephrol. 2021, 53, 1955–1961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, T.; Jeong, I.G.; You, D.; Park, M.C.; Hong, J.H.; Ahn, H.; Kim, C. Effect of prostate size on pathological outcome and biochemical recurrence after radical prostatectomy for prostate cancer: Is it correlated with serum testosterone level? BJU Int. 2010, 106, 633–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiu, P.K.F.; Leow, J.J.; Chiang, C.H.; Mok, A.; Zhang, K.; Hsieh, P.F.; Zhu, Y.; Lam, W.; Tsang, W.-C.; Fan, Y.-H.; et al. Prostate Health Index Density Outperforms Prostate-specific Antigen Density in the Diagnosis of Clinically Significant Prostate Cancer in Equivocal Magnetic Resonance Imaging of the Prostate: A Multicenter Evaluation. J. Urol. 2023, 210, 88–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thompson, I.M.; Goodman, P.J.; Tangen, C.M.; Parnes, H.L.; Minasian, L.M.; Godley, P.A.; Lucia, M.S.; Ford, L.G. Long-Term Survival of Participants in the Prostate Cancer Prevention Trial. N. Engl. J. Med. 2013, 369, 603–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andriole, G.L.; Bostwick, D.G.; Brawley, O.W.; Gomella, L.G.; Marberger, M.; Montorsi, F.; Pettaway, C.A.; Tammela, T.L.; Teloken, C.; Tindall, D.J. Effect of dutasteride on the risk of prostate cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2010, 362, 1192–1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Ghita, K.M.; Wadera, A.; Alabousi, M.; Pozdnyakov, A.; Kashif Al-ghita, M.; Jafri, A.; McInnes, M.D.; Schieda, N.; van der Pol, C.B.; Salameh, J.-P.; et al. Impact of PI-RADS Category 3 lesions on the diagnostic accuracy of MRI for detecting prostate cancer and the prevalence of prostate cancer within each PI-RADS category: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Br. J. Radiol. 2020, 94, 20191050. [Google Scholar]

- Drevik, J.; Dalimov, Z.; Uzzo, R.; Danella, J.; Guzzo, T.; Belkoff, L.; Raman, J.; Tomaszewski, J.; Trabulsi, E.; Reese, A.; et al. Utility of PSA density in patients with PI-RADS 3 lesions across a large multi-institutional collaborative. Urol. Oncol. Semin. Orig. Investig. 2022, 40, e1–e490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, J.; Liu, W.; Shen, X.; Hu, W. PI-RADS v2.1 and PSAD for the prediction of clinically significant prostate cancer among patients with PSA levels of 4–10 ng/ml. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 6570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Omri, N.; Kamil, M.; Alexander, K.; Alexander, K.; Edmond, S.; Ariel, Z.; David, K.; Gilad, A.E.; Azik, H. Association between PSA density and pathologically significant prostate cancer: The impact of prostate volume. Prostate 2020, 80, 1444–1449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, J.T.; Barocas, D.; Carlsson, S.; Coakley, F.; Eggener, S.; Etzioni, R.; Fine, S.W.; Han, M.; Kim, S.K.; Kirkby, E.; et al. Early Detection of Prostate Cancer: AUA/SUO Guideline Part I: Prostate Cancer Screening. J. Urol. 2023, 210, 46–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Prostate Volume by MRI (mL) | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Group 1 (n = 160) | Group 2 (n = 193) | ||

| Age (y) | 68.6 ± 7.8 | 68.5 ± 6.9 | 0.95 |

| PSA (ng/mL) | 5.9 (4.5–9.2) | 7.0 (5.4–10.0) | 0.002 |

| DRE suspected n (%) | 19 (13.0) | 9 (4.3) | 0.02 |

| Prostate volume (mL) | 33.0 (27.0–37.0) | 65.5 (54.0–84.0) | - |

| Max PIRADS | 0.15 | ||

| 1–2 n (%) | 7 (4.7) | 12 (5.7) | |

| 3 n (%) | 22 (15.0) | 47 (22.7) | |

| 4–5 n (%) | 135 (92.4) | 131 (63.2) | |

| Number of samples ROI, n | 7.5 ± 3.1 | 8.8 ± 3.8 | <0.001 |

| Number of random samples, n | 6.9 ± 2.5 | 7.6 ± 2.6 | 0.02 |

| PSA Density (ng/mL2) | 0.18 (0.13–0.29) | 0.11 (0.08–0.15) | <0.001 |

| Variable | Prostate Volume by MRI (mL) | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Group 1 (n = 160) | Group 2 (n = 193) | ||

| Any cancer n (%) | 119 (74.3) | 69 (35.5) | <0.001 |

| Cancer in ROI n (%) | 114 (71.2) | 62 (32.1) | <0.001 |

| CSPC in ROI n (%) | 68 (42.5) | 38 (19.6) | <0.001 |

| CSPC in random n (%) | 41 (25.6) | 15 (7.6) | <0.001 |

| Max ISUP grade group | <0.001 | ||

| 1 n (%) | 43 (26.8) | 30 (15.5) | |

| 2 n (%) | 35 (21.8) | 17 (8.6) | |

| 3 n (%) | 18 (11.2) | 11 (5.6) | |

| 4 n (%) | 17 (10.6) | 8 (4.0) | |

| 5 n (%) | 6 (3.7) | 3 (1.5) | |

| Prostatic Volume (mL) < 44 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Univariate | Multivariate * | |||

| OR (95% CI) | p | OR (95% CI) | p | |

| All patients | ||||

| Prostatic cancer | 5.30 (3.29–8.47) | <0.001 | 7.31 (4.22–12.7) | <0.001 |

| CSPC | 3.50 (2.17–5.65) | <0.001 | 5.08 (2.87–8.99) | <0.001 |

| High risk PC | 2.73 (1.28–5.84) | 0.009 | 4.50 (1.80–11.3) | 0.001 |

| PIRADS 3 | PIRADS 4–5 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All Cancers | CSPC | HRPC | All Cancers | CSPC | HRPC | |

| Group 1 | 10 | 4 | 1 | 107 | 69 | 21 |

| Group 2 | 5 | 1 | 0 | 59 | 37 | 11 |

| p-value | 0.003 | 0.003 | 0.32 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.09 |

| End-Point\Predictor | Prostatic Volume (mL) < 44 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Univariate | Multivariate * | |||

| OR (95% CI) | p | OR (95% CI) | p | |

| PIRADS 3 | ||||

| Any cancer | 5.55 (1.55–18.8) | 0.008 | 15.3 (2.44–95.5) | 0.004 |

| CSPC | 12.8 (1.39–118.4) | 0.03 | 16.9 (1.59–178.7) | 0.02 |

| High risk PC | - | - | ||

| PIRADS 4–5 | ||||

| Any cancer | 5.46 (3.07–9.69) | <0.001 | 7.63 (4.04–14.4) | <0.001 |

| CSPC | 2.83 (1.68–4.77) | <0.001 | 4.35 (2.34–8.09) | <0.001 |

| High risk PC | 2.16 (0.99–4.71) | 0.05 | 3.59 (1.43–9.01) | 0.007 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tiger, S.; Shpunt, I.; Beberashvili, I.; Avda, Y.; Smolyakov, V.; Lerman, D.; Goldshtein, G.; Shahabri, W.; Rubinshtein, D.; Jaber, M.; et al. Influence of Prostate Volume on Targeted Biopsy Outcomes and PI-RADS Predictive Value for Significant Prostate Cancer. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 8476. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238476

Tiger S, Shpunt I, Beberashvili I, Avda Y, Smolyakov V, Lerman D, Goldshtein G, Shahabri W, Rubinshtein D, Jaber M, et al. Influence of Prostate Volume on Targeted Biopsy Outcomes and PI-RADS Predictive Value for Significant Prostate Cancer. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(23):8476. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238476

Chicago/Turabian StyleTiger, Shir, Igal Shpunt, Ilia Beberashvili, Yuval Avda, Vadim Smolyakov, Dmitry Lerman, Gal Goldshtein, Wael Shahabri, Dor Rubinshtein, Morad Jaber, and et al. 2025. "Influence of Prostate Volume on Targeted Biopsy Outcomes and PI-RADS Predictive Value for Significant Prostate Cancer" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 23: 8476. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238476

APA StyleTiger, S., Shpunt, I., Beberashvili, I., Avda, Y., Smolyakov, V., Lerman, D., Goldshtein, G., Shahabri, W., Rubinshtein, D., Jaber, M., Croock, R., Abu Marsa, A., Shilo, Y., Modai, J., & Leibovici, D. (2025). Influence of Prostate Volume on Targeted Biopsy Outcomes and PI-RADS Predictive Value for Significant Prostate Cancer. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(23), 8476. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238476