When Stroke Strikes Early: Unusual Causes of Intracerebral Hemorrhage in Young Adults

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Data Source

2.2. Study Population

2.3. Variables

2.4. Outcomes

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Cohort Characteristics

3.2. Comorbidities and Outcomes

3.3. Rare Etiologies

3.4. Procedures and Discharge Disposition

3.5. Multivariable Analysis

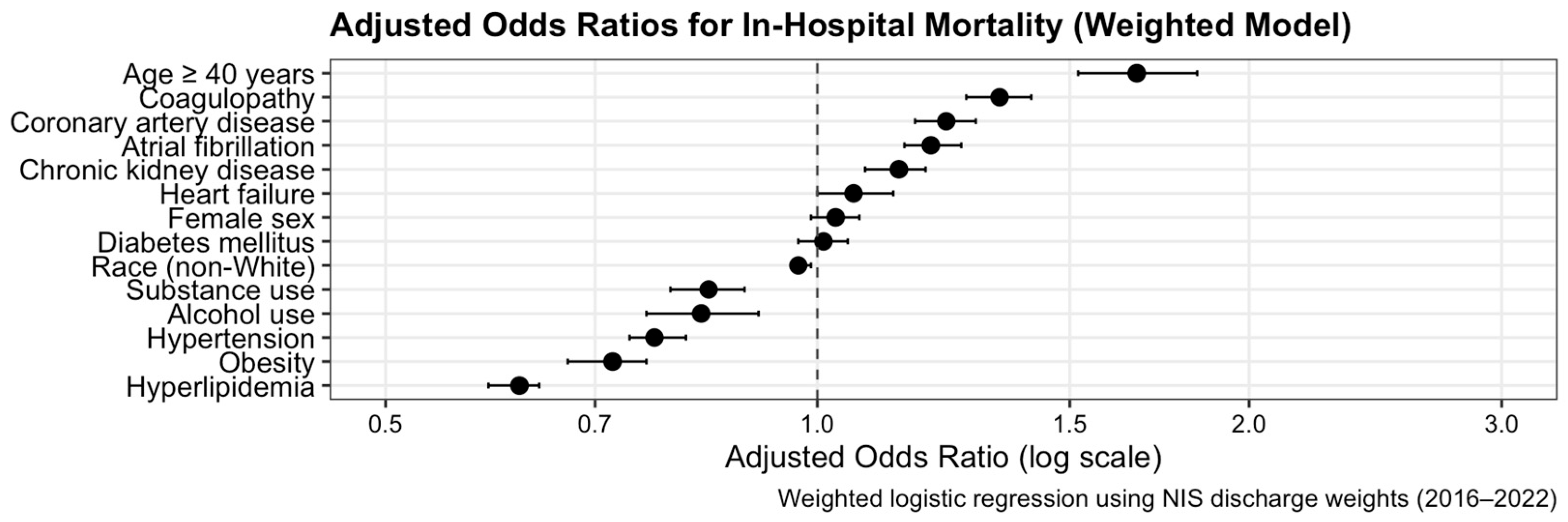

3.6. Subgroup and Interaction Analyses

4. Discussion

5. Limitations

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kim, J.; Thayabaranathan, T.; Donnan, G.A.; Howard, G.; Howard, V.J.; Rothwell, P.M.; Feigin, V.; Norrving, B.; Owolabi, M.; Pandian, J.; et al. Global stroke statistics 2019. Int. J. Stroke 2020, 15, 819–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheth, K.N. Spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage. N. Engl. J. Med. 2022, 387, 1589–1596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hankey, G.J. Stroke. Lancet 2017, 389, 641–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerstl, J.V.E.; Blitz, S.E.; Qu, Q.R.; Yearley, A.G.; Lassarén, P.; Lindberg, R.; Gupta, S.; Kappel, A.D.; Vicenty-Padilla, J.C.; Gaude, E.; et al. Global, regional, and national economic consequences of stroke. Stroke 2023, 54, 2380–2389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Wang, Z.; Wu, W.; Li, M.; Li, Q. Global, regional, and national burden of intracerebral hemorrhage and its attributable risk factors from 1990 to 2021: Results from the 2021 global burden of disease study. BMC Public Health 2024, 24, 2426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lioutas, V.A.; Beiser, A.S.; Aparicio, H.J.; Himali, J.J.; Selim, M.H.; Romero, J.R.; Seshadri, S. Assessment of incidence and risk factors of intracerebral hemorrhage among participants in the Framingham Heart Study between 1948 and 2016. JAMA Neurol. 2020, 77, 1252–1260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schutte, A.E.; Srinivasapura Venkateshmurthy, N.; Mohan, S.; Prabhakaran, D. Hypertension in low- and middle-income countries. Circ. Res. 2021, 128, 808–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, S.J.; Kim, T.J.; Yoon, B.W. Epidemiology, risk factors, and clinical features of intracerebral hemorrhage: An update. J. Stroke 2017, 19, 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magid-Bernstein, J.; Girard, R.; Polster, S.; Srinath, A.; Romanos, S.; Awad, I.A.; Sansing, L.H. Cerebral hemorrhage: Pathophysiology, treatment, and future directions. Circ. Res. 2022, 130, 1204–1229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laurent, S.; Boutouyrie, P. The structural factor of hypertension: Large and small artery alterations. Circ. Res. 2015, 116, 1007–1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keep, R.F.; Hua, Y.; Xi, G. Intracerebral haemorrhage: Mechanisms of injury and therapeutic targets. Lancet Neurol. 2012, 11, 720–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chung, J.; Montgomery, B.; Marini, S.; Rosand, J.; Anderson, C.D. Genome-wide interaction study with sex identifies novel loci for intracerebral hemorrhage risk. Arterioscler. Thromb. Amd Vasc. Biol. 2019, 39, A571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy-O’Reilly, M.; McCullough, L.D. Sex differences in stroke: The contribution of coagulation. Exp. Neurol. 2014, 259, 16–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Larsson, S.C.; Burgess, S.; Michaelsson, K. Smoking and stroke: A mendelian randomization study. Ann. Neurol. 2019, 86, 468–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rigotti, N.A.; Clair, C. Managing tobacco use: The neglected cardiovascular disease risk factor. Eur. Heart J. 2013, 34, 3259–3267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.J.; Ding, D.; Derdeyn, C.P.; Lanzino, G.; Friedlander, R.M.; Southerland, A.M.; Lawton, M.T.; Sheehan, J.P. Brain arteriovenous malformations: A review of natural history, pathobiology, and interventions. Neurology 2020, 95, 917–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, E.R. Cavernous malformations of the central nervous system. N. Engl. J. Med. 2024, 390, 1022–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saposnik, G.; Bushnell, C.; Coutinho, J.M.; Field, T.S.; Furie, K.L.; Galadanci, N.; Kam, W.; Kirkham, F.C.; McNair, N.D.; Singhal, A.B.; et al. Diagnosis and management of cerebral venous thrombosis: A scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Stroke 2024, 55, e77–e90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez, N.R.; Amin-Hanjani, S.; Bang, O.Y.; Coffey, C.; Du, R.; Fierstra, J.; Fraser, J.F.; Kuroda, S.; Tietjen, G.E.; Yaghi, S. Adult Moyamoya disease and syndrome: Current perspectives and future directions: A scientific statement from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke 2023, 54, e465–e479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox, C.K.; Leykina, L.; Hills, N.K.; Kwiatkowski, J.L.; Kanter, J.; Strouse, J.J.; Voeks, J.H.; Fullerton, H.J.; Adams, R.J.; Post-STOP Study Group. Hemorrhagic stroke in children and adults with sickle cell anemia: The Post-STOP cohort. Stroke 2022, 53, e463–e466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorgalaleh, A.; Farshi, Y.; Haeri, K.; Baradarian Ghanbari, O.; Ahmadi, A. Risk and management of intracerebral hemorrhage in patients with bleeding disorders. Semin. Thromb. Hemost. 2022, 48, 344–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghadimi, K.; Shapouran, S. Epidemiology and pathophysiology of primary versus secondary intracranial hemorrhage in pregnant and nonpregnant patients: A literature review. Clin. Neurol. Neurosurg. 2025, 257, 109056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, H.; Patel, U.K.; Chowdhury, M.; Assaf, A.D.; Avanthika, C.; Nor, M.A.; Rage, M.; Madapu, A.; Konatham, S.; Vodapally, M.; et al. Substance use disorders (SUDs) and risk of cardiovascular disease (CVD) and cerebrovascular disease (CeVD): Analysis of the Nationwide Inpatient Sample (NIS) database. Cureus 2023, 15, e39331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Osman, S.; Zhu, Z.; Farag, M.; Groysman, L.; Dastur, C.; Akbari, Y.; Stern-Nezer, S.; Stradling, D.; Yu, W. Intracerebral hemorrhage: Who gets tested for methamphetamine use and why might it matter? BMC Neurol. 2020, 20, 392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Béjot, Y.; Cordonnier, C.; Mebazaa, A. Spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage in young adults: A narrative review of the main causes. Rev. Neurol. 2019, 175, 619–626. [Google Scholar]

- Levecque, M.; Goutagny, S.; Toussaint, P.; Naggara, O.; Bresson, D.; Sakka, L.; Froelich, S. Etiology, risk factors, and prognosis of intracerebral hemorrhage in young adults. Rev. Neurol. 2017, 173, 551–557. [Google Scholar]

- Kizilay, F.; Gökçal, E.; Tascilar, N. Intracerebral hemorrhage in young adults: Aetiology, risk factors, and outcome. Turk. J. Neurol. 2021, 27, 213–220. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, X.; Liu, Y.; Chen, S.; Chen, D.; Wu, X.; Wu, Y.; Liu, C.; Manyande, A.; Xiang, H.; Tang, Z. Intracerebral hemorrhage: The global differential burden and secular trends from 1990 to 2019 and its prediction up to 2030. Int. J. Public Health 2025, 70, 1607013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristic | 18–39 Years (n = 4012) | ≥40 Years (n = 72,252) |

|---|---|---|

| Mean age (years) | 28.9 | 69.2 |

| Male (%) | 59.3 | 52.5 |

| Hypertension (%) | 47.8 | 84.1 |

| Diabetes mellitus (E08–E13) (%) | 10.2 | 60.4 |

| Chronic kidney disease (%) | 9.9 | 17.6 |

| Coagulopathy (%) | 11.9 | 12.9 |

| Alcohol use (%) | 6.9 | 7.2 |

| Substance use (%) | 27.7 | 15.6 |

| Race–White (%) | 49.8 | 64.2 |

| Race–Black (%) | 25.4 | 17.8 |

| Race–Hispanic (%) | 18.6 | 12.1 |

| Outcome | 18–39 Years | ≥40 Years | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| In-hospital mortality (%) | 15.7 | 21.7 | <0.001 |

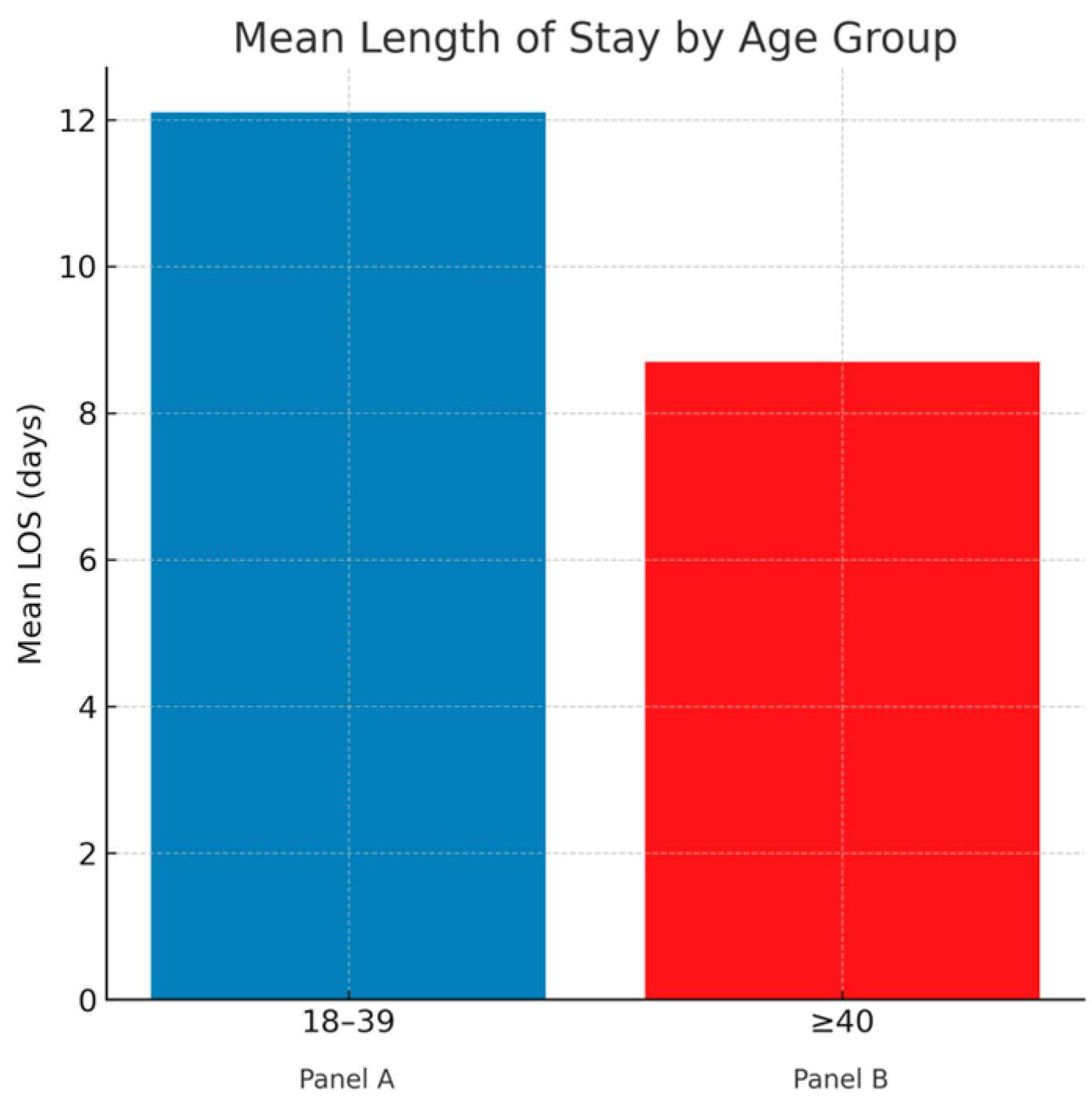

| Mean length of stay (days) | 12.1 ± 0.4 | 8.7 ± 0.2 | <0.001 |

| Median length of stay (days) | 6 | 5 | – |

| Mean hospital charges (USD) | 228,000 ± 8500 | 125,000 ± 4200 | <0.001 |

| Median hospital charges (USD) | 115,000 | 64,000 | – |

| Discharged home (%) | 42.1 | 17.2 | <0.001 |

| Discharged to rehabilitation/other facility (%) | 28.9 | 46.5 | <0.001 |

| Home health care (%) | 5.8 | 10.7 | <0.001 |

| In-hospital death (%) | 15.7 | 21.7 | <0.001 |

| Rare Etiology (ICD-10-CM Codes) | 18–39 Years (%) | ≥40 Years (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Arteriovenous malformation/aneurysm (Q28.2–Q28.3, I67.1, I72.x) | 14.0 | 3.6 |

| Brain tumor (C70–C72, C79.3, D33.x) | 2.1 | 0.7 |

| Moyamoya disease (I67.5) | 1.4 | 0.2 |

| Sickle cell disease (D57.x) | 1.1 | 0.1 |

| Infection (G00–G03) | 1.5 | 0.4 |

| Vasculitis (I77.6, M30–M31) | 0.6 | 0.1 |

| Cerebral venous sinus thrombosis (I67.6, G08) | 1.8 | 0.36 |

| Pregnancy-related ICH (O10–O16, O22.5, O87.3) | 0.05 | 0.00 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Urfy, M.; Tariq Mir, M. When Stroke Strikes Early: Unusual Causes of Intracerebral Hemorrhage in Young Adults. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 8475. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238475

Urfy M, Tariq Mir M. When Stroke Strikes Early: Unusual Causes of Intracerebral Hemorrhage in Young Adults. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(23):8475. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238475

Chicago/Turabian StyleUrfy, Mian, and Mariam Tariq Mir. 2025. "When Stroke Strikes Early: Unusual Causes of Intracerebral Hemorrhage in Young Adults" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 23: 8475. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238475

APA StyleUrfy, M., & Tariq Mir, M. (2025). When Stroke Strikes Early: Unusual Causes of Intracerebral Hemorrhage in Young Adults. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(23), 8475. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238475