Assessment of Overall Muscle Strength in Children and Adolescents Using Handheld Dynamometry: A Systematic Review of Reference Values and Quality of Data

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Study Selection Process

2.3. Study Eligibility

Inclusion Criteria

2.4. Exclusion Criteria

2.5. Search Strategy

2.6. Data Extraction

2.7. Risk of Bias (Quality) Assessment

2.8. Data Synthesis and Grouping

3. Results

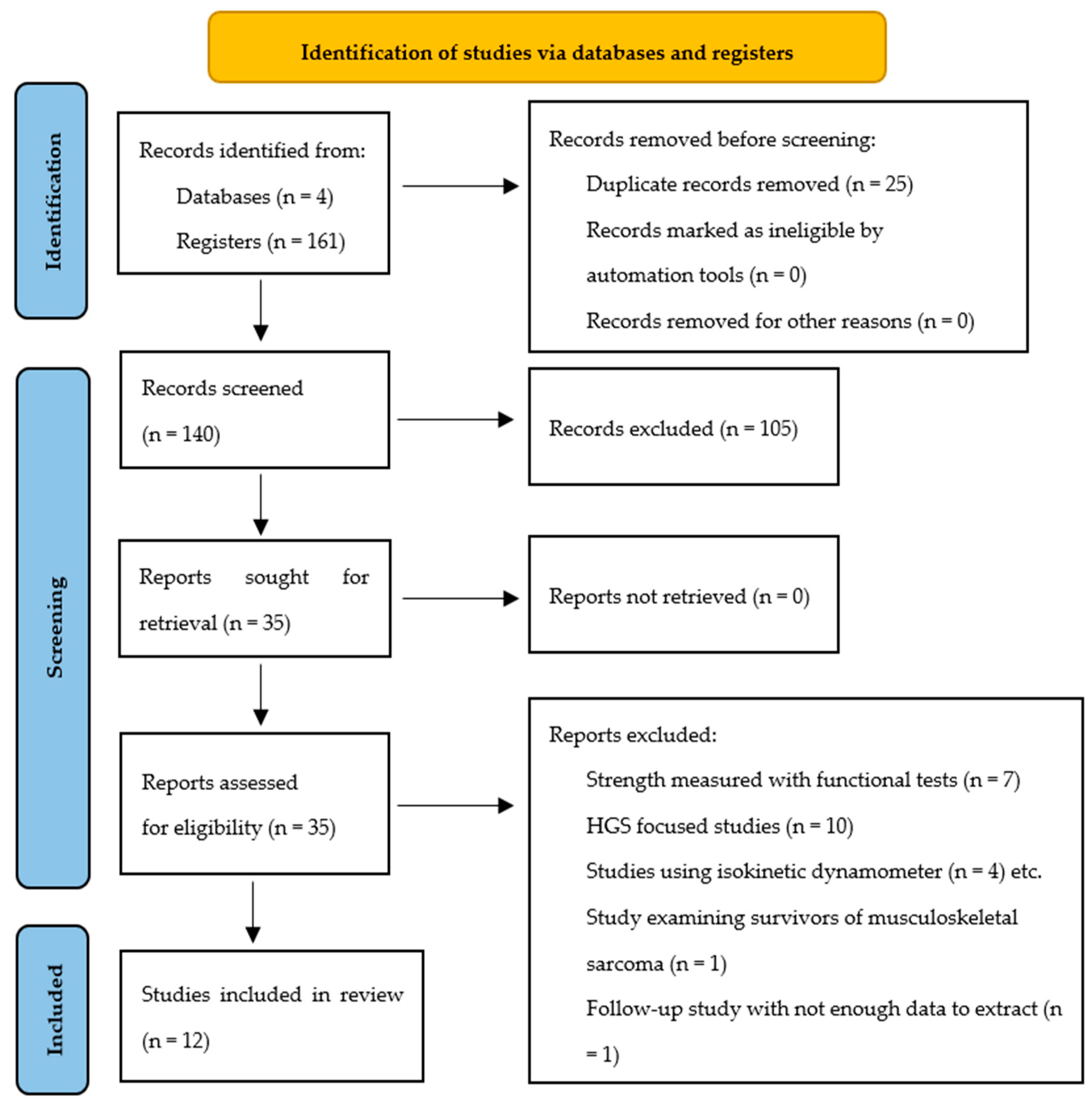

3.1. Study Selection

3.2. Study Characteristics

3.3. Risk of Bias Assessment

3.4. Muscle Groups

3.5. Summary of Evidence on Measurement Properties

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ABD | Abductor |

| ADD | Adductor |

| DMN | Dominant |

| ER | External rotation |

| F | Female |

| HGS | Handgrip strength |

| HHD | Handheld dynamometer |

| IVMC | Isometric voluntary muscle contraction |

| JBI | Joanna Briggs Institute |

| kg | Kilogram |

| Lb | Pound |

| LQYBT | Lower Quarter Y Balance Test |

| LR | Lateral rotation |

| M | Male |

| Min | Minutes |

| MIT | Maximal isometric torque |

| N | Newton |

| Nm | Newton-meter |

| No | Number of participants |

| MR | Medial rotation |

| PRISMA | Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews |

Appendix A

| No of Studies | Study Design | Risk of Bias | Inconsistency | Indirectness | Imprecision | Other Considerations | Intervention | Comparison | Certainty Importance | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 [22] | Non-randomized studies Cohort study | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | None | 74/74 (100.0%) | 37/74 (50.0%) | Low | Acceptable intra- and inter-rater reliability and concurrent validity with the Cybex. |

| 8 [4,5,7,23,24,25,26,27] | Non-randomized studies Cross-sectional studies | Serious * | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | None | −1511 | 1511/1511 (100.0%) | Very low | Variation among studies regarding the muscle groups tested, fixation protocols, and data analysis or presentation. |

| 3 [28,29,30] | Non-randomized studies Reliability and Criterion Validity | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | None | 98 | 98/98 (100.0%) | Low | Test re-test reliability and low measurement error for hallux and lesser toe flexor strength. Reliable knee extension joint torque measurements using HHDs. Poor concurrent validity of HHDs in children 7–11 years old compared to Isokinetic Dynamometer |

References

- US Department of Health and Human Services. Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans, 2nd ed.; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services: Washington, DC, USA, 2018. Available online: https://health.gov/sites/default/files/2019-09/Physical_Activity_Guidelines_2nd_edition.pdf (accessed on 8 September 2024).

- Muehlbauer, T.; Gollhofer, A.; Granacher, U. Associations Between Measures of Balance and Lower-Extremity Muscle Strength/Power in Healthy Individuals Across the Lifespan: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Sp. Med. 2015, 45, 1671–1692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Delezie, J.; Handschin, C. Endocrine Crosstalk Between Skeletal Muscle and the Brain. Front. Neurol. 2018, 9, 698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daloia, L.M.T.; Leonardi-Figueiredo, M.M.; Martinez, E.Z.; Mattiello-Sverzut, A.C. Isometric muscle strength in children and adolescents using Handheld dynamometry: Reliability and normative data for the Brazilian population. Braz. J. Phys. Ther. 2018, 22, 474–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hébert, L.J.; Maltais, D.B.; Lepage, C.; Saulnier, J.; Crête, M. Hand-Held Dynamometry Isometric Torque Reference Values for Children and Adolescents. Ped Phys. Ther. 2015, 27, 414–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohannon, R.W. Manual muscle testing: Does it meet the standards of an adequate screening test? Clin. Rehabil. 2005, 19, 662–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendez-Rebolledo, G.; Ruiz-Gutierrez, A.; Salas-Villar, S.; Guzman-Muñoz, E.; Sazo-Rodriguez, S.; Urbina-Santibáñez, E. Isometric strength of upper limb muscles in youth using hand-held and handgrip dynamometry. J. Exerc. Rehabil. 2022, 18, 203–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mentiplay, B.F.; Perraton, L.G.; Bower, K.J.; Adair, B.; Pua, Y.H.; Williams, G.P.; McGaw, R.; Clark, R.A. Assessment of Lower Limb Muscle Strength and Power Using Hand-Held and Fixed Dynamometry: A Reliability and Validity Study. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0140822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulder-Brouwer, A.N.; Rameckers, E.A.A.; Bastiaenen, C.H. Lower Extremity Handheld Dynamometry Strength Measurement in Children With Cerebral Palsy. Ped Phys. Ther. 2016, 28, 136–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stark, T.; Walker, B.; Phillips, J.K.; Fejer, R.; Beck, R. Hand-held Dynamometry Correlation With the Gold Standard Isokinetic Dynamometry: A Systematic Review. PM&R 2011, 3, 472–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsiros, M.D.; Grimshaw, P.N.; Shield, A.J.; Buckley, J.D. The Biodex Isokinetic Dynamometer for knee strength assessment in children: Advantages and limitations. Work 2011, 39, 161–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bimali, I.; Opsana, R.; Jeebika, S. Normative reference values on handgrip strength among healthy adults of Dhulikhel, Nepal: A cross-sectional study. J. Family Med. Prim. Care 2020, 9, 310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steiber, N. Strong or Weak Handgrip? Normative Reference Values for the German Population across the Life Course Stratified by Sex, Age, and Body Height. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0163917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leong, D.P.; Teo, K.K.; Rangarajan, S.; Kutty, V.R.; Lanas, F.; Hui, C.; Quanyong, X.; Zhenzhen, Q.; Jinhua, T.; Noorhassim, I.; et al. Reference ranges of handgrip strength from 125,462 healthy adults in 21 countries: A prospective urban rural epidemiologic (PURE) study. J. Cachexia Sarc Muscle 2016, 7, 535–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gómez-Campos, R.; Vidal Espinoza, R.; De Arruda, M.; Ronque, E.R.; Urra-Albornoz, C.; Minango, J.C.; Alvear-Vasquez, F.; la Torre Choque, C.D.; Castelli Correia de Campos, L.F.; Sulla Torres, J.; et al. Relationship between age and handgrip strength: Proposal of reference values from infancy to senescence. Front. Public Health 2023, 10, 1072684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraser, B.J.; Blizzard, L.; Buscot, M.J.; Schmidt, M.D.; Dwyer, T.; Venn, A.J.; Magnussen, C.G. Muscular strength across the life course: The tracking and trajectory patterns of muscular strength between childhood and mid-adulthood in an Australian cohort. J. Sci. Med. Sport 2021, 24, 696–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geffré, A.; Friedrichs, K.; Harr, K.; Concordet, D.; Trumel, C.; Braun, J. Reference values: A review. Vet. Clin. Pathol. 2009, 38, 288–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morin, M.; Duchesne, E.; Bernier, J.; Blanchette, P.; Langlois, D.; Hébert, L.J. What is Known About Muscle Strength Reference Values for Adults Measured by Hand-Held Dynamometry: A Scoping Review. Arch. Rehabil. Res. Clin. Transl. 2022, 4, 100172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aromataris, E.; Lockwood, C.; Porritt, K.; Pilla, B.; Jordan, Z. (Eds.) JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis; JBI: Adelaide, Australia, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mokkink, L.B.; De Vet, H.C.; Prinsen, C.A.; Patrick, D.L.; Alonso, J.; Bouter, L.M.; Terwee, C.B. COSMIN Risk of Bias checklist for systematic reviews of Patient-Reported Outcome Measures. Qual. Life Res. 2018, 27, 1171–1179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hébert, L.J.; Maltais, D.B.; Lepage, C.; Saulnier, J.; Crête, M.; Perron, M. Isometric Muscle Strength in Youth Assessed by Hand-held Dynamometry. Ped Phys. Th. 2011, 23, 289–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macfarlane, T.S.; Larson, C.A.; Stiller, C. Lower Extremity Muscle Strength in 6- to 8-Year-Old Children Using Hand-Held Dynamometry. Ped Phys. Th. 2008, 20, 128–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escobar, R.G.; Munoz, K.T.; Dominguez, A.; Banados, P.; Bravo, M.J. Maximal isometric muscle strength values obtained By hand-held dynamometry in children between 6 and 15 years of age. Muscle Nerve. 2017, 55, 16–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peek, K.; Gatherer, D.; Bennett, K.J.M.; Fransen, J.; Watsford, M. Muscle strength characteristics of the hamstrings and quadriceps in players from a high-level youth football (soccer) Academy. Res. Sports Med. 2018, 26, 276–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alhusaini, A.A.; Melam, G.; Buragadda, S. The role of body mass index on dynamic balance and muscle strength in Saudi schoolchildren. Sci. Sports 2020, 35, e1–e395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šarčević, Z.; Savić, D.; Tepavčević, A. Correlation between isometric strength in five muscle groups and inclination angles of spine. Eur. Spine J. 2020, 29, 161–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rock, K.; Nelson, C.; Addison, O.; Marchese, V. Assessing the Reliability of Handheld Dynamometry and Ultrasonography to Measure Quadriceps Strength and Muscle Thickness in Children, Adolescents, and Young Adults. Phys. Occup. Ther. Pediatr. 2021, 41, 540–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quinlan, S.; Sinclair, P.; Hunt, A.; Fong Yan, A. Excellent reliability of toe strength measurements in children aged ten to twelve years achieved with a novel fixed dynamometer. Gait Posture. 2021, 85, 20–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahaffey, R.; Le Warne, M.; Morrison, S.C.; Drechsler, W.I.; Theis, N. Concurrent Validity of Lower Limb Muscle Strength by Handheld Dynamometry in Children 7 to 11 Years Old. J. Sport Rehabil. 2022, 31, 1089–1094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beenakker, E.A.C.; van der Hoeven, J.H.; Fock, J.M.; Maurits, N.M. Reference values of maximum isometric muscle force obtained in 270 children aged 4–16 years by hand-held dynamometry. Neuromusc. Disord. 2001, 11, 441–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merriam-Webster. Norm. 2022. Available online: https://www.merriamwebster.com/dictionary/norm (accessed on 22 August 2025).

- Karagianni, E.; Stojiljkovic, A.; Antoniou, V.; Batalik, L.; Pepera, G. Modeling the associations of cardiorespiratory fitness with the cardiometabolic profile and sedentary behavior in school-aged nonprofessional athletes. Gazz. Medica Ital. Arch. Per Le Sci. Mediche 2025, 184, 183–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stojiljkovic, A.; Karagianni, E.; Antoniou, V.; Pepera, G. Relationship Between Physical Fitness Attributes and Dynamic Knee Valgus in Adolescent Basketball Athletes. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 4881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattiello-Sverzut, A.C. Response to the letter to the Editor entitled, “The (un)standardized use of handheld dynamometers on the evaluation of muscle force output”. Braz. J. Phys. Ther. 2020, 24, 89–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alvarenga, G.; Kiyomoto, H.D.; Martinez, E.C.; Polesello, G.; Alves, V.L.d.S. Normative isometric hip muscle force values assessed by a manual dynamometer. Acta Ortop. Bras. 2019, 27, 124–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thorborg, K.; Bandholm, T.; Hölmich, P. Hip- and knee-strength assessments using a hand-held dynamometer with external belt-fixation are inter-tester reliable. Knee Surg. Sports Traumatol. Arthrosc. 2013, 21, 550–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van der Ploeg, R.J.; Fidler, V.; Oosterhuis, H.J. Hand-held myometry: Reference values. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 1991, 54, 244–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pepera, G.; Hadjiandrea, S.; Iliadis, I.; Sandercock, G.R.H.; Batalik, L. Associations between cardiorespiratory fitness, fatness, hemodynamic characteristics, and sedentary behaviour in primary school-aged children. BMC Sports Sci. Med. Rehabil. 2022, 14, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eek, M.N.; Kroksmark, A.K.; Beckung, E. Isometric Muscle Torque in Children 5 to 15 Years of Age: Normative Data. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2006, 87, 1091–1099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, P.R.; McKay, M.J.; Baldwin, J.N.; Burns, J.; Pareyson, D.; Rose, K.J. Repeatability, consistency, and accuracy of hand-held dynamometry with and without fixation for measuring ankle plantarflexion strength in healthy adolescents and adults. Muscle Nerve 2017, 56, 896–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hogrel, J.Y.; Payan, C.A.; Ollivier, G.; Tanant, V.; Attarian, S.; Couillandre, A.; Dupeyron, A.; Lacomblez, L.; Doppler, V.; Meininger, V.; et al. Development of a French Isometric Strength Normative Database for Adults Using Quantitative Muscle Testing. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2007, 88, 1289–1297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díez-Fernández, A.; Sánchez-López, M.; Gulías-González, R.; Notario-Pacheco, B.; Cañete García-Prieto, J.; Arias-Palencia, N.; Martínez-Vizcaíno, V. BMI as a Mediator of the Relationship between Muscular Fitness and Cardiometabolic Risk in Children: A Mediation Analysis. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0116506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valtueña, J.; Gracia-Marco, L.; Huybrechts, I.; Breidenassel, C.; Ferrari, M.; Gottrand, F.; Dallongeville, J.; Sioen, I.; Gutierrez, A.; Kersting, M.; et al. Cardiorespiratory fitness in males, and upper limbs muscular strength in females, are positively related with 25-hydroxyvitamin D plasma concentrations in European adolescents: The HELENA study. QJM 2013, 106, 809–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Data Extracted |

|---|

| Authors Year Country Sample Age Sex Number of participants HHD model Measurement units HHD maximal capacity (N, lb, kg) Mode (compression/traction) Contraction type Instructions Protocol reproducibility (positioning for measurement) HHD placement Muscle groups tested Results Limits reported Other |

| JBI Cohort | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hebert et al., 2011 [22] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Unclear | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| JBI Cross Sectional | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Macfarlane et al., 2008 [23] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes |

| Hebert et al., 2015 [5] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Unclear | Yes | Yes |

| Escobar et al., 2017 [24] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Daloia et al., 2018 [4] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Unclear | Unclear | Yes | Yes |

| Peek et al., 2018 [25] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Unclear | Unclear | Yes | Yes |

| Alhusaini et al., 2019 [26] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Unclear | Unclear | Yes | Yes |

| Šarčević et al., 2019 [27] | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Unclear | Yes | Yes |

| Mendez-Rebolledo et al., 2022 [7] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Unclear | Yes | Yes |

| COSMIN Risk of Bias | Were Patients Stable in the Interim Period on the Construct to be Measured? | Was the Time Interval Appropriate? | Were the Test Conditions Similar for the Measurements? E.g., Type of Administration, Environment, Instructions | For Continuous Scores: Was an Intraclass Correlation Coefficient (ICC) Calculated? | Were There Any Other Important Flaws in the Design or Statistical Methods of the Study? | Overall Methodological Quality | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Box 6 Reliability | ||||||||||

| Rock et al., 2021 [28] | Adequate | Very good | Very good | Very good | Very good | Adequate | ||||

| Quinlan et al., 2021 [29] | Very good | Very good | Very good | Very good | Very Good | Very good | ||||

| Box 8 Criterion Validity | Statistical methods | Other | Overall methodological quality | |||||||

| Mahafey et al., 2022 [30] | Very good | Very good | Very good | |||||||

| Authors | Country/Region | Participants | Age (Mean ± SD) | Type of Dynamometer and Measurement Unit | Testing Procedures | Type of Muscle Contraction and Sides Tested | Muscle Groups and Assessment Position | Study Objective |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Macfarlane et al., 2008 [23] | Michigan, USA | No = 154 F = 90 M = 64 | Pooled for age, 6–8 age groups | MicroFET2 [Hoggan Scientific, LLC, Salt Lake City, UT, USA] Force: N | Mode: Compression Test trials: 3 Total test duration: 25–30 min Evaluators: 1 Stabilization: No | Contraction type: Make test Isometric [Bilateral] | Hip ABD/ADD: Supine Hip flexors/extensors: Sidelying [Hips and knees flexed at 45°] Knee flexors/extensors: Seated | Establishing muscle force and torque reference values for 6-to-8 years old |

| Hebert et al., 2011 [22] | Québec, Canada | No = 74 F = 37 M = 37 | 10,7 ± 4 [4–17.5 years old 9 age groups] | [1] Lafayette Instrument, Model 01163 [Lafayette Instrument Company, Lafayette, IN, USA] and [2] FCE-500 Ametek TCI Division [C.S.C. Force Measurement, Inc., Agawam, MA, USA] Force: N, Torque: Nm | Mode: Compression and Distraction for lower limb muscles Test trials: 2 Total test duration: 45 min, 4 sessions, 5–14 days apart Evaluators: 2 Stabilization: Yes for knee extensors, No for the rest of muscle groups | Contraction type: Make test Isometric [Bilateral for older participants and randomly selected one sided test for ages 4–8.5] | Shoulder ABD: Supine [1] Shoulder LR: Supine [1] Elbow flexors/extensors: Supine [1] Hip flexors/extensors: Supine [2] Hip ABD: Supine [1] Knee flexors/extensors: Seated [1] Ankle plantar flexors/dorsiflexors: Supine [1] | Feasibility, intra- and interrater reliability, SEMs, concurrent validity statistics |

| Hebert et al., 2015 [5] | North America | No = 348 F = 174 M = 174 | Pooled for age, 4–17 age groups | FCE-500 Ametek TCI Division [C.S.C. Force Measurement, Inc., Agawam, MA, USA] Torque: Nm | Mode: Compression and Distraction for hip flexors and extensors only Test trials: 3 Total test duration: Not disclosed Evaluator: 6 (2 Per school) Stabilization: Yes, for hip flexors and extensors, not for the rest of muscle groups | Contraction type: Make test Isometric [Bilateral for older participants and randomly selected one sided test for ages 4–8.5] | Shoulder ABD and ER: Supine Elbow flexors/extensors: Supine Hip flexors/extensors: Supine Hip ABD: Supine Knee flexors/extensors: Seated Ankle dorsiflexors: Supine | Reference values establishment Comparison of torque between absolute and reference values Comparison of muscle strength profiles |

| Escobar et al., 2017 [24] | Chile | No = 400 F = 213 M = 187 | Pooled for age, 6–15 age groups | Lafayette Instrument, Model 01163 [Lafayette Instrument Company, Lafayette, IN, USA] Force: N | Mode: Compression Test trials: 3–5 Total test duration: 30–40 min Evaluators: 3 Stabilization: No | Contraction type: Break test Isometric [Bilateral] | Shoulder flexors/ABD: Seated Elbow flexors/extensors: Supine Wrist flexors/extensors: Supine Hip flexors/ABD: Supine Knee extensors: Seated Ankle plantar flexors/dorsiflexors: Supine | Muscle strength values determination |

| Daiola et al., 2018 [4] | São Paulo, Brazil | No = 110 F = 55 M = 55 | Pooled for age, 5–15 age groups | Lafayette Instrument [Lafayette Instrument Company, Lafayette, IN, USA] Force: N | Mode: Compression Test trials: 3 Total test duration: Not disclosed Evaluators: 2 Stabilization: No | Contraction type: Not disclosed [Push command] Isometric [Bilateral] | Shoulder ABD: Supine Elbow flexors/extensors: Supine Knee flexors/extensors: Seated Ankle plantar flexors/dorsiflexors: Supine | Description of the development of isometric muscle strength and the evaluation of inter and intra-rater reliability |

| Peek et al., 2018 [25] | Australia | No = 142 M = 142 | Pooled for age, 8–15 age groups | GS Gatherer and GS Analysis Suite® [Gatherer Systems Limited, Aylesbury, UK] Force: N | Mode: Not disclosed [Assumed Distraction] Test trials: 2 Total test Duration: 20–30 min Evaluators: 1 Stabilization: Yes | Contraction type: Break test Isometric [Bilateral] | Knee flexors/extensors: Prone [Hamstring/quadriceps ratio] | Investigation of IVMCmax characteristics of the hamstrings and quadriceps in youth football players |

| Alhusaini et al., 2019 [26] | Riyadh, Saudi Arabia | No = 51 M = 51 | 14.17 ± 0.71 | Lafayette Instrument, Model 01165 [Lafayette Instrument Company, Lafayette, IN, USA] Force: N | Mode: Compression Test trials: 3 Total test duration: Not disclosed Evaluators: Not disclosed Stabilization: No | Contraction type: Make test Isometric [Bilateral] | Knee flexors/extensors: Seated | Relationship between BMI scores, LQYBT performance, and the lower-limb strength of schoolchildren |

| Šarčević et al., 2019 [27] | Novi Sad, Serbia | Νo = 63 F = 32 M = 31 | 12.73 ± 1.58 | JTECH Commander PowerTrack Muscle Dynamometer [JTECH Medical, Midvale, UT, USA] Force: N | Mode: Assumed Compression Test trials: 3 * Total test duration: Not disclosed Evaluators: 1 Stabilization: Yes | Contraction mode: Not disclosed Isometric [there was no side-testing disclosure.] | DMN Lower trapezius: Prone row position. DMN Serratus anterior and upper trapezius: Seated 120–130° Shoulder flexion Hip ABD: Supine Hip extension: Prone with the knee flexed to 90° Erector spinae: on hands and knees bent at 90° | Correlation study between maximum isometric strength in five muscle groups |

| Rock et al., 2021 [28] | Baltimore, MD, USA | No = 23 F = 13 M = 10 | 7.18 ± 1.15 [6–8 years old] 10.16 ± 0.71 [9–11 years old] 14.74 ± 2.01 [12–17 years old] | Lafayette Instrument, Model 01165 [Lafayette Instrument Company, Lafayette, IN, USA] Force: N | Mode: Compression Test trials: 3 Total test duration: Not disclosed Evaluators: 1 Stabilization: No | Contraction type: Not disclosed Isometric [Dominant lower extremity] | Knee extensors: seated 90° and 35°; supine 90° and 35° | Reliability of the use of HHDs and ultrasonography to measure quadriceps strength |

| Quinlan et al., 2021 [29] | Australia | No = 14 F = 8 M = 6 | 11.25 ± 0.38 | Lafayette Instrument, Model 01163 [Lafayette Instrument Company, Lafayette, IN, USA] Force: N | Mode: Compression Test trials: 2 Total test duration: Not disclosed [2 sessions, 7–14 days apart] Evaluators: 1 Stabilization: Yes | Contraction type: Not disclosed Isometric [Dominant foot] | Toe plantar flexors: seated [Hallux and Lesser toes] | Test–retest reliability of a novel fixed HHD protocol |

| Mahafey et al., 2022 [30] | United Kingdom | No = 61 F = 28 M = 33 | 9.20 ± 0.98 | Wagner ForceOne FDIX [Wagner Instruments, Greenwich, CT, USA] Force: N Torque: Nm | Mode: Assumed Compression Test trials: 2 Total test duration: approx. 15 min Evaluators: 2 Stabilization: Yes, on the contralateral leg | Contraction type: Make test Isometric [dominant lower extremity] | Hip flexion: Supine Hip ADD/ABD: Sidelying Knee flexors/extensors: Seated Ankle plantar flexors/dorsiflexors: Prone | Concurrent validity of lower limb torque from HHDs compared to isokinetic dynamometry in children aged 7-to-11 years old |

| Mendez- Rebolledo et al., 2022 [7] | Chile | No = 243 F = 114 M = 129 | Pooled for age, 7–15 age groups | Lafayette Instrument, Model 01165 [Lafayette Instrument Company, Lafayette, IN, USA] Force: N; N/Kg (Body mass) | Mode: Compression Test trials: 3 Total test duration: 60 min Evaluators: 1 Stabilization: No | Contraction type: Make test Isometric [Dominant upper extremity] | Shoulder ABD/flexors/LR /MR: Seated Elbow flexors/extensors: Supine Wrist flexors/extensors: Supine | Determining the isometric strength profile of the upper limb muscles of children and adolescents |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Karagianni, E.; Antoniou, V.; Dimitriadis, Z.; Panagiotakos, D.; Cordovil, R.; Pepera, G. Assessment of Overall Muscle Strength in Children and Adolescents Using Handheld Dynamometry: A Systematic Review of Reference Values and Quality of Data. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 8454. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238454

Karagianni E, Antoniou V, Dimitriadis Z, Panagiotakos D, Cordovil R, Pepera G. Assessment of Overall Muscle Strength in Children and Adolescents Using Handheld Dynamometry: A Systematic Review of Reference Values and Quality of Data. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(23):8454. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238454

Chicago/Turabian StyleKaragianni, Eleni, Varsamo Antoniou, Zacharias Dimitriadis, Demosthenes Panagiotakos, Rita Cordovil, and Garyfallia Pepera. 2025. "Assessment of Overall Muscle Strength in Children and Adolescents Using Handheld Dynamometry: A Systematic Review of Reference Values and Quality of Data" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 23: 8454. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238454

APA StyleKaragianni, E., Antoniou, V., Dimitriadis, Z., Panagiotakos, D., Cordovil, R., & Pepera, G. (2025). Assessment of Overall Muscle Strength in Children and Adolescents Using Handheld Dynamometry: A Systematic Review of Reference Values and Quality of Data. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(23), 8454. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238454