Cerebral, Muscle and Blood Oxygenation in Patients with Pulmonary Vascular Disease Whilst Breathing Normobaric Hypoxia vs. Normoxia Before and After Sildenafil: Data from a Randomised Controlled Trial

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

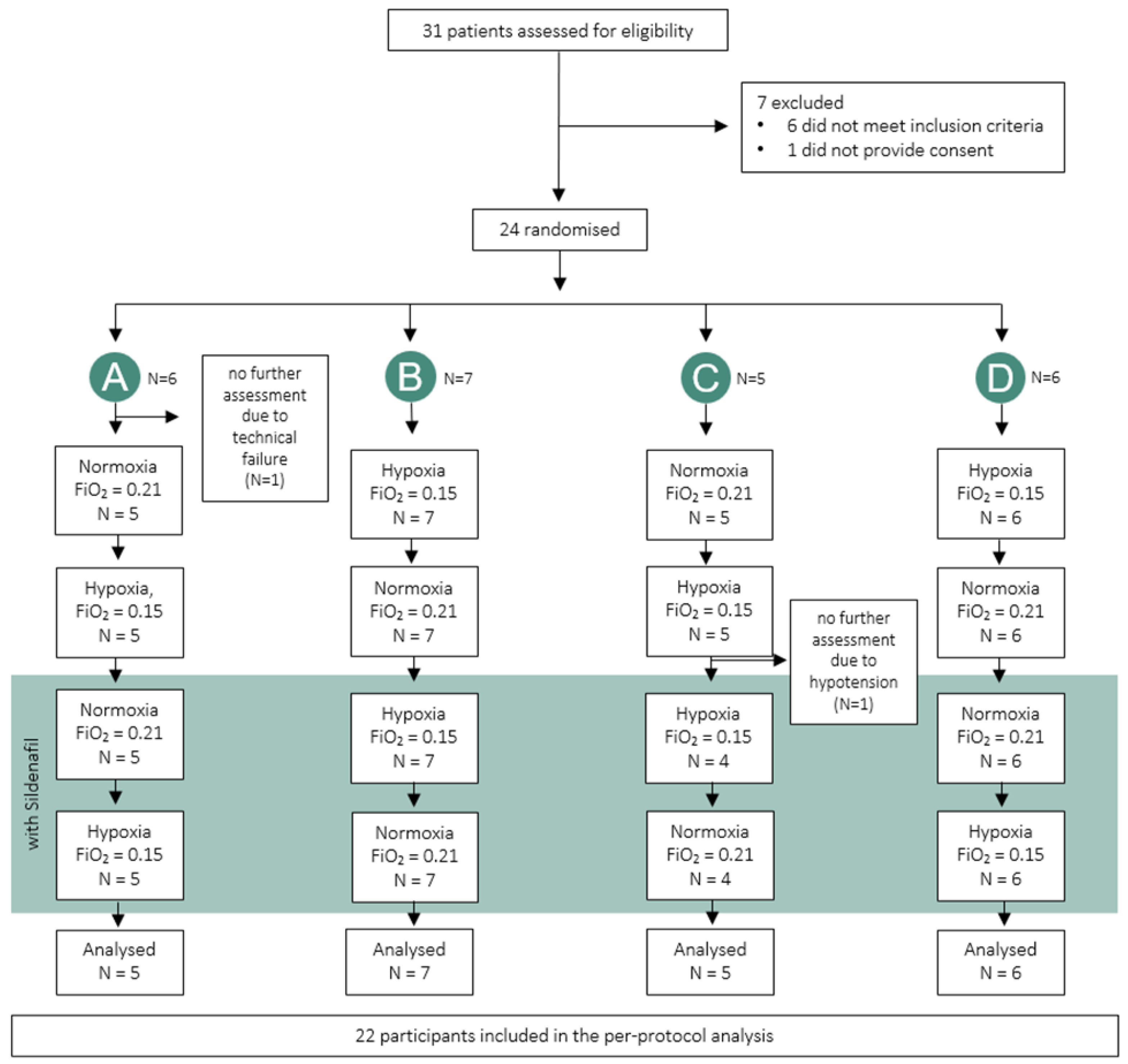

2.1. Design and Setting

2.2. Participants

2.3. Intervention, Randomization and Blinding

2.4. Assessments

2.4.1. Baseline Medical History

2.4.2. Cerebral and Muscle Tissue Oxygenation by NIRS

2.4.3. Blood Gas Analysis and Oximetry

2.4.4. Right Heart Catheterization and Metabolic Measurements

2.4.5. Outcomes

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BP | blood pressure |

| CaO2 | arterial oxygen content |

| CTEPH | chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension |

| cTHI | cerebral tissue hemoglobin index |

| CTO | cerebral tissue oxygenation saturation |

| HHb | relative concentration of deoxygenated hemoglobin |

| HPV | hypoxic pulmonary vasoconstriction |

| mTHI | muscular tissue hemoglobin index |

| MTO | muscular tissue oxygenation saturation |

| NIRS | near-infrared spectroscopy |

| NYHA | New York Heart Association |

| O2Hb | relative concentration of oxygenated hemoglobin |

| PAH | pulmonary arterial hypertension |

| PaCO2 | arterial partial pressure of carbon dioxide |

| PaO2 | arterial partial pressure of oxygen |

| PAP | pulmonary artery pressure |

| PAWP | Pulmonary arterial wedge pressure |

| PH | pulmonary hypertension |

| PVD | pulmonary vascular disease |

| RAP | right atrial pressure |

| RHC | right heart catheterization |

| SpO2 | peripheral oxygen saturation |

| SVR | systemic vascular resistance |

| totHb | sum of O2Hb and HHb |

References

- Beaudin, A.E.; Hartmann, S.E.; Pun, M.; Poulin, M.J. Human cerebral blood flow control during hypoxia: Focus on chronic pulmonary obstructive disease and obstructive sleep apnea. J. Appl. Physiol. 2017, 123, 1350–1361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ainslie, P.N.; Burgess, K.R. Cardiorespiratory and cerebrovascular responses to hyperoxic and hypoxic rebreathing: Effects of acclimatization to high altitude. Respir. Physiol. Neurobiol. 2008, 161, 201–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Rawi PG, S.P.; Kirkpatrick, P.J. Evaluation of a near-infrared spectrometer (NIRO 300) for the detection of intracranial oxygenation changes in the adult head. Stroke 2001, 32, 2492–2500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Keijzer, I.N.; Massari, D.; Sahinovic, M.; Flick, M.; Vos, J.J.; Scheeren, T.W. What is new in microcirculation and tissue oxygenation monitoring? J. Clin. Monit. Comput. 2022, 36, 291–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Rawi, P.G.; Kirkpatrick, P.J. Tissue oxygen index: Thresholds for cerebral ischemia using near-infrared spectroscopy. Stroke 2006, 37, 2720–2725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Highton, D.; Panovska-Griffiths, J.; Ghosh, A.; Tachtsidis, I.; Banaji, M.; Elwell, C.; Smith, M. Modelling cerebrovascular reactivity: A novel near-infrared biomarker of cerebral autoregulation? Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2013, 765, 87–93. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Humbert, M.; Kovacs, G.; Hoeper, M.M.; Badagliacca, R.; Berger, R.M.; Brida, M.; Carlsen, J.; Coats, A.J.; Escribano-Subias, P.; Ferrari, P.; et al. 2022 ESC/ERS Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of pulmonary hypertension. Eur. Heart. J. 2022, 43, 3618–3731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovacs, G.; Bartolome, S.; Denton, C.P.; Gatzoulis, M.A.; Gu, S.; Khanna, D.; Badesch, D.; Montani, D. Definition, classification and diagnosis of pulmonary hypertension. Eur. Respir. J. 2024, 64, 2401324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulrich, S.; Fischler, M.; Speich, R.; Bloch, K.E. Wrist actigraphy predicts outcome in patients with pulmonary hypertension. Respiration 2013, 86, 45–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ulrich, S.; Schneider, S.R.; Bloch, K.E. Effect of hypoxia and hyperoxia on exercise performance in healthy individuals and in patients with pulmonary hypertension: A systematic review. J. Appl. Physiol. 2017, 123, 1657–1670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornwell, W.K., III; Baggish, A.L.; Bhatta, Y.K.D.; Brosnan, M.J.; Dehnert, C.; Guseh, J.S.; Hammer, D.; Levine, B.D.; Parati, G.; Wolfel, E.E. Clinical Implications for Exercise at Altitude Among Individuals with Cardiovascular Disease: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. J. Am. Heart. Assoc. 2021, 10, e023225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Titz, A.; Hoyos, R.; Ulrich, S. Pulmonary vascular diseases at high altitude-is it safe to live in the mountains? Curr. Opin. Pulm. Med. 2024, 30, 459–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poudel, S.; Gautam, S.; Adhikari, P.; Zafren, K. Physiological Effects of Sildenafil Versus Placebo at High Altitude: A Systematic Review. High. Alt. Med. Biol. 2024, 25, 16–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, S.R.; Lichtblau, M.; Müller, J.; Bauer, M.; Mayer, L.; Schwarz, E.I.; Furian, M.; Saxer, S.; Ulrich, S. Acute effects of 50 mg additive oral sildenafil on invasive exercise haemodynamics in pulmonary vascular disease. ERJ Open. Res. 2025, 11, 01392–02024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumas, J.P.; Bardou, M.; Goirand, F.; Dumas, M. Hypoxic pulmonary vasoconstriction. Gen. Pharmacol. 1999, 33, 289–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lichtblau, M.; Schneider, S.R.; Müller, J.; Bauer, M.; Carta, A.F.; Mayer, L.; Schwarz, E.I.; Furian, M.; Saxer, S.; Ulrich, S. Effect of Normobaric Hypoxia on Invasive Exercise Hemodynamics in Patients with Pulmonary Vascular Disease: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2025, 211, 657–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simonneau, G.; Montani, D.; Celermajer, D.S.; Denton, C.P.; Gatzoulis, M.A.; Krowka, M.; Williams, P.G.; Souza, R. Haemodynamic definitions and updated clinical classification of pulmonary hypertension. Eur. Respir. J. 2019, 53, 1801913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olopade, C.O.; Mensah, E.; Gupta, R.; Huo, D.; Picchietti, D.L.; Gratton, E.; Michalos, A. Noninvasive determination of brain tissue oxygenation during sleep in obstructive sleep apnea: A near-infrared spectroscopic approach. Sleep 2007, 30, 1747–1755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furian, M.; Latshang, T.D.; Aeschbacher, S.S.; Ulrich, S.; Sooronbaev, T.; Mirrakhimov, E.M.; Aldashev, A.; Bloch, K.E. Cerebral oxygenation in highlanders with and without high-altitude pulmonary hypertension. Exp. Physiol. 2015, 100, 905–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwarz, E.I.; Furian, M.; Schlatzer, C.; Stradling, J.R.; Kohler, M.; Bloch, K.E. Nocturnal cerebral hypoxia in obstructive sleep apnoea: A randomised controlled trial. Eur. Respir. J. 2018, 51, 1800032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ulrich, S.; Nussbaumer-Ochsner, Y.; Vasic, I.; Hasler, E.; Latshang, T.D.; Kohler, M.; Muehlemann, T.; Wolf, M.; Bloch, K.E. Cerebral oxygenation in patients with OSA: Effects of hypoxia at altitude and impact of acetazolamide. Chest 2014, 146, 299–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Groth, A.; Saxer, S.; Bader, P.R.; Lichtblau, M.; Furian, M.; Schneider, S.R.; Schwarz, E.I.; Bloch, K.E.; Ulrich, S. Acute hemodynamic changes by breathing hypoxic and hyperoxic gas mixtures in pulmonary arterial and chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension. Int. J. Cardiol. 2018, 270, 262–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kovacs, G.; Avian, A.; Olschewski, A.; Olschewski, H. Zero reference level for right heart catheterisation. Eur. Respir. J. 2013, 42, 1586–1594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warburton, D.E.; Haykowsky, M.J.; Quinney, H.A.; Humen, D.P.; Teo, K.K. Reliability and Validity of Measures of Cardiac Output During Incremental to Maximal Aerobic Exercise Part I: Conventional Techniques. Sports Med 1999, 27, 23–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Forrer, A.; Gaisl, T.; Sevik, A.; Meyer, M.; Senteler, L.; Lichtblau, M.; Bloch, K.E.; Ulrich, S.; Furian, M. Partial Pressure of Arterial Oxygen in Healthy Adults at High Altitudes: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. JAMA Netw. Open 2023, 6, e2318036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruopp, N.F.; Cockrill, B.A. Diagnosis and Treatment of Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension: A Review. JAMA 2022, 327, 1379–1391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sylvester, J.T.; Shimoda, L.A.; Aaronson, P.I.; Ward, J.P. Hypoxic pulmonary vasoconstriction. Physiol. Rev 2012, 92, 367–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carta, A.F.; Lichtblau, M.; Berlier, C.; Saxer, S.; Schneider, S.R.; Schwarz, E.I.; Furian, M.; Bloch, K.E.; Ulrich, S. The Impact of Breathing Hypoxic Gas and Oxygen on Pulmonary Hemodynamics in Patients with Pulmonary Hypertension. Front. Med. 2022, 9, 791423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagdyman, N.; Fleck, T.; Bitterling, B.; Ewert, P.; Abdul-Khaliq, H.; Stiller, B.; Hübler, M.; Lange, P.E.; Berger, F.; Schulze-Neick, I. Influence of intravenous sildenafil on cerebral oxygenation measured by near-infrared spectroscopy in infants after cardiac surgery. Pediatr. Res. 2006, 59, 462–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, C.W.; Hoar, H.; Pattinson, K.; Bradwell, A.R.; Wright, A.D.; Imray, C.H. Effect of sildenafil and acclimatization on cerebral oxygenation at altitude. Clin. Sci. 2005, 109, 319–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCormick, P.W.; Stewart, M.; Goetting, M.G.; Balakrishnan, G. Regional cerebrovascular oxygen saturation measured by optical spectroscopy in humans. Stroke 1991, 22, 596–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolff, C.B.; Imray, C.H. Partitioning of arterial and venous volumes in the brain under hypoxic conditions. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2003, 540, 19–23. [Google Scholar]

- Lichtblau, M.; Berlier, C.; Saxer, S.; Carta, A.F.; Mayer, L.; Groth, A.; Bader, P.R.; Schneider, S.R.; Furian, M.; Schwarz, E.I.; et al. Acute Hemodynamic Effect of Acetazolamide in Patients With Pulmonary Hypertension Whilst Breathing Normoxic and Hypoxic Gas: A Randomized Cross-Over Trial. Front. Med. 2021, 8, 681473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Müller-Mottet, S.; Hildenbrand, F.F.; Keusch, S.; Hasler, E.; Maggiorini, M.; Speich, R.; Bloch, K.E.; Ulrich, S. Effects of exercise and vasodilators on cerebral tissue oxygenation in pulmonary hypertension. Lung 2015, 193, 113–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schneider, S.R.; Lichtblau, M.; Furian, M.; Mayer, L.C.; Berlier, C.; Müller, J.; Saxer, S.; Schwarz, E.I.; Bloch, K.E.; Ulrich, S. Cardiorespiratory Adaptation to Short-Term Exposure to Altitude vs. Normobaric Hypoxia in Patients with Pulmonary Hypertension. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 2769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vermeij, A.; Van Beek, A.H.; Olde Rikkert, M.G.; Claassen, J.A.; Kessels, R.P. Effects of aging on cerebral oxygenation during working-memory performance: A functional near-infrared spectroscopy study. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e46210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable N = 22 | Value |

|---|---|

| Sex, ♀/♂ (%) | 9/13 (41/59) |

| Age, y | 54 ± 14 |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 26.3 ± 4.0 |

| New York Heart Association functional class I, II, III, IV (%) | 1 (4), 16 (73), 5 (23), 0 (0) |

| 6-min walk distance, m | 553 ± 78 |

| Pulmonary hypertension classification, n (%) | |

| Pulmonary arterial hypertension | 14 (64) |

| Idiopathic/hereditary | 12 |

| Connective tissue disease | 1 |

| Portal hypertension | 1 |

| Chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension | 8 (36) |

| Pulmonary function and hemodynamic | |

| Resting PaO2, kPa | 9.6 ± 1.2 |

| Mean pulmonary arterial pressure, mmHg | 40 ± 11 |

| Pulmonary vascular resistance, Wood units | 6.0 ± 2.7 |

| Pulmonary hypertension targeted therapy, n (%) | |

| Endothelin receptor antagonist | 9 (41) |

| Phosphodiesterase-5 inhibitor | 9 (41) |

| Soluble guanylate cyclase stimulators | 3 (14) |

| Prostacyclin receptor agonist or prostacyclin | 6 (27) |

| Combination therapy | 8 (36) |

| No PH-specific therapy | 8 (36) |

| Normoxia (N) | Hypoxia (H) | Normoxia After Sildenafil (NS) | Hypoxia After Sildenafil (HS) | Mean Difference ∆ H-N (95% CI) | Sildenafil Effect on Normoxia, Mean Difference ∆ NS-N (95% CI) | Mean Difference ∆ HS-NS (95% CI) | Sildenafil Effect on Hypoxia, Mean Difference ∆HS-H (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

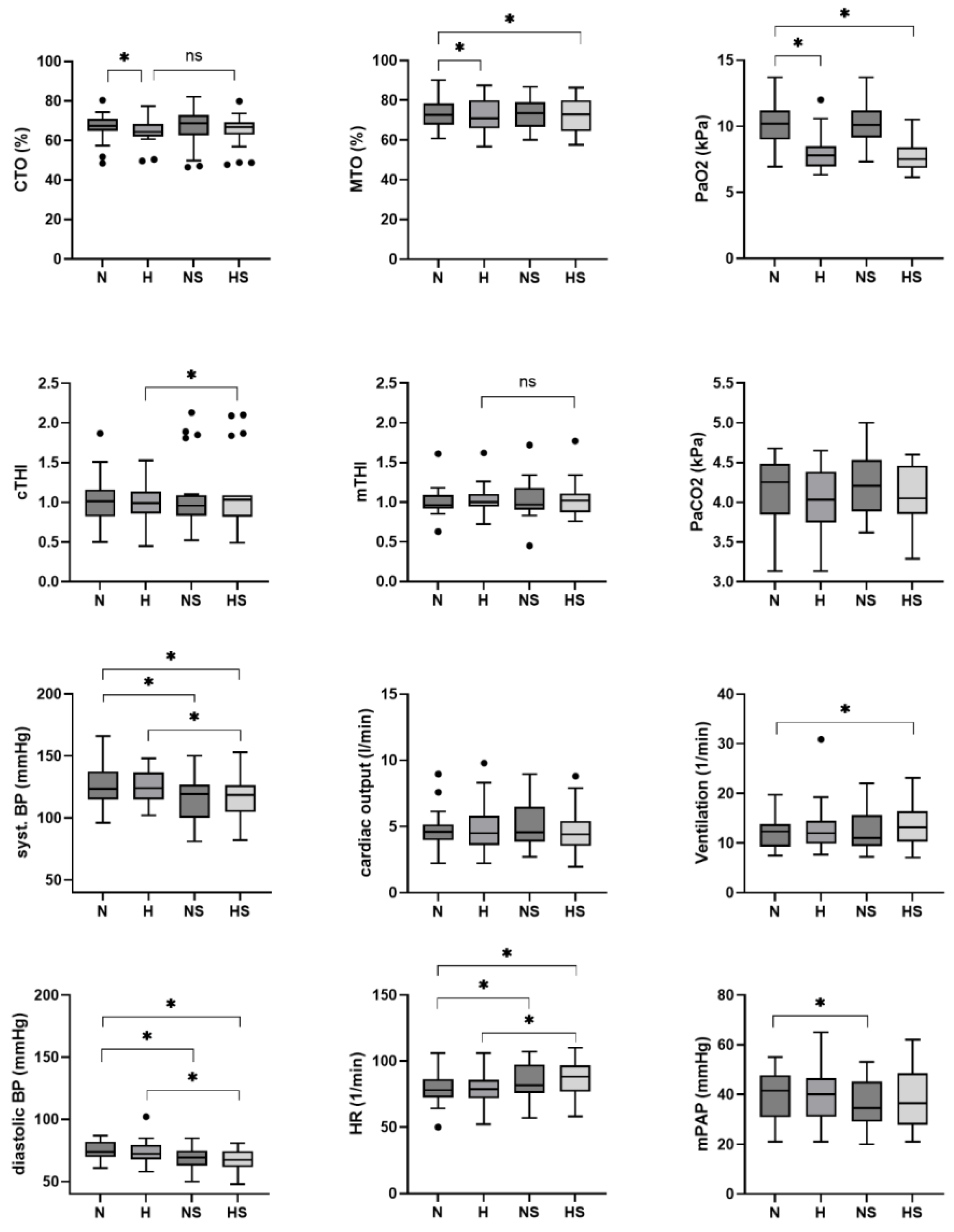

| Tissue oxygenation | ||||||||

| CTO, % | 66 ± 2 | 64 ± 2 | 67 ± 2 | 65 ± 2 | −2 (−4 to 0) * | 0 (−2 to 2) | −2 (−4 to 0) * | 0 (−2 to 2) |

| cTHI | 1.02 ± 0.09 | 0.99 ± 0.09 | 1.09 ± 0.09 | 1.11 ± 0.09 | −0.02 (−0.14 to 0.09) | 0.07 (−0.04 to 0.19) | 0.03 (−0.09 to 0.14) | 0.12 (0.00 to 0.23) * |

| MTO, % | 73 ± 2 | 72 ± 2 | 72 ± 2 | 72 ± 2 | −1 (−3 to 0) * | −1 (−2 to 0) | −1 (−2 to 0) | 0 (−1 to 1) |

| mTHI | 1.01 ± 0.05 | 1.04 ± 0.05 | 1.04 ± 0.05 | 1.05 ± 0.05 | 0.03 (−0.02 to 0.09) | 0.03 (−0.02 to 0.09) | 0.01 (−0.04 to 0.07) | 0.01 (−0.04 to 0.07) |

| Blood gas analysis and Ventilation | ||||||||

| Hemoglobin, g/dL | 15.4 ± 0.3 | 15.5 ± 0.3 | 15.4 ± 0.3 | 15.4 ± 0.3 | 0.1 (−0.1 to 0.2) | 0.0 (−0.2 to 0.1) | 0.0 (−0.1 to 0.2) | −0.1 (−0.2 to 0.1) |

| Lactate, mmol/L | 0.9 ± 0.1 | 0.7 ± 0.1 | 1.4 ± 0.1 | 1.2 ± 0.1 | −0.1 (−0.3 to 0.0) | 0.5 (0.3 to 0.7) * | −0.2 (−0.4 to 0.0) | 0.5 (0.3 to 0.6) * |

| pHa | 7.45 ± 0.01 | 7.47 ± 0.01 | 7.44 ± 0.01 | 7.46 ± 0.01 | 0.01 (0.00 to 0.03) * | −0.01 (−0.02 to 0.00) | 0.01 (0.00 to 0.02) * | −0.01 (−0.02 to 0.00) |

| PaO2, kPa | 10.1 ± 0.3 | 7.9 ± 0.3 | 10.1 ± 0.3 | 7.6 ± 0.3 | −2.3 (−2.7 to −1.8) * | 0.0 (−0.5 to 0.5) | −2.6 (−3.0 to −2.1) * | −0.3 (−0.8 to 0.2) |

| PaCO2, kPa | 4.1 ± 0.1 | 4.0 ± 0.1 | 4.2 ± 0.1 | 4.1 ± 0.1 | −0.1 (−0.3 to 0.0) | 0.1 (−0.1 to 0.3) | −0.2 (−0.3 to 0.0) * | 0.0 (−0.1 to 0.2) |

| SaO2, % | 94 ± 1 | 90 ± 1 | 95 ± 1 | 90 ± 1 | −4 (−5 to −3) * | 0 (−1 to 2) | −5 (−6 to −4) * | −1 (−2 to 0) |

| CaO2, mL/L | 193 ± 4 | 185 ± 4 | 192 ± 4 | 182 ± 4 | −8 (−11 to −5) * | −1 (−4 to 2) | −10 (−13 to −7) * | −3 (−6 to 0) |

| PmvO2, kPa | 4.9 ± 0.1 | 4.5 ± 0.1 | 4.9 ± 0.1 | 4.6 ± 0.1 | −0.3 (−0.5 to −0.2) * | 0.1 (−0.1 to 0.2) | −0.3 (−0.5 to −0.2) * | 0.0 (−0.1 to 0.2) |

| PmvCO2, kPa | 4.8 ± 0.1 | 4.7 ± 0.1 | 4.9 ± 0.1 | 4.6 ± 0.1 | −0.1 (−0.3 to 0.1) | 0.1 (0.0 to 0.3) | −0.3 (−0.4 to −0.1) * | 0.0 (−0.2 to 0.1) |

| SvO2, % | 67 ± 1 | 63 ± 1 | 65 ± 1 | 63 ± 1 | −4 (−7 to −1) * | −2 (−4 to 1) | −2 (−5 to 0) | 0 (−3 to 3) |

| Hemodynamics | ||||||||

| Heart rate, bpm | 78 ± 3 | 79 ± 3 | 84 ± 3 | 87 ± 3 | 1 (−2 to 4) | 5 (2 to 9) * | 3 (0 to 6) | 8 (5 to 11) * |

| Syst. BP, mmHg | 128 ± 4 | 126 ± 4 | 115 ± 4 | 117 ± 4 | −2 (−7 to 2) | −13 (−18 to −9) * | 2 (−3 to 6) | −9 (−13 to −4) * |

| Dia. BP, mmHg | 75 ± 2 | 75 ± 2 | 69 ± 2 | 67 ± 2 | −1 (−4 to 2) | −7 (−9 to −4) * | −1 (−4 to 1) | −7 (−10 to −5) * |

| Respiratory Rate, 1/min | 12 ± 1 | 13 ± 1 | 12 ± 1 | 14 ± 1 | 1 (0 to 2) | 0 (−1 to 2) | 1 (0 to 2) | 1 (−1 to 2) |

| Mean PAP, mmHg | 39 ± 2 | 40 ± 2 | 36 ± 2 | 38 ± 2 | 1 (−2 to 3) | −3 (−6 to −1) * | 2 (−1 to 4) | −2 (−5 to 0) |

| Cardiac output, L/min | 4.7 ± 0.4 | 4.9 ± 0.4 | 5.1 ± 0.4 | 4.7 ± 0.4 | 0.2 (−0.5 to 0.8) | 0.4 (−0.3 to 1.0) | −0.4 (−1.1 to 0.2 | −0.2 (−0.9 to 0.5) |

| SVR, WU | 20.6 ± 1.7 | 20.7 ± 1.7 | 18.0 ± 1.7 | 19.0 ± 1.7 | 0.1 (−2.0 to 2.3) | −2.6 (−4.8 to −0.5) * | 1.0 (−1.1 to 3.2) | −1.7 (−3.9 to 0.5 |

| PVR, WU | 7.10 ± 0.81 | 7.16 ± 0.82 | 5.99 ± 0.82 | 6.75 ± 0.81 | 0.06 (−0.92 to 1.05) | −1.11 (−2.09 to −0.13) * | 0.76 (−0.22 to 1.74) | −0.42 (−1.40 to 0.57) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Häfliger, A.; Furian, M.; Schneider, S.R.; Müller, J.; Bauer, M.; Carta, A.F.; Schwarz, E.I.; Saxer, S.; Lichtblau, M.; Ulrich, S. Cerebral, Muscle and Blood Oxygenation in Patients with Pulmonary Vascular Disease Whilst Breathing Normobaric Hypoxia vs. Normoxia Before and After Sildenafil: Data from a Randomised Controlled Trial. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 8407. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238407

Häfliger A, Furian M, Schneider SR, Müller J, Bauer M, Carta AF, Schwarz EI, Saxer S, Lichtblau M, Ulrich S. Cerebral, Muscle and Blood Oxygenation in Patients with Pulmonary Vascular Disease Whilst Breathing Normobaric Hypoxia vs. Normoxia Before and After Sildenafil: Data from a Randomised Controlled Trial. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(23):8407. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238407

Chicago/Turabian StyleHäfliger, Alina, Michael Furian, Simon R. Schneider, Julian Müller, Meret Bauer, Arcangelo F. Carta, Esther I. Schwarz, Stéphanie Saxer, Mona Lichtblau, and Silvia Ulrich. 2025. "Cerebral, Muscle and Blood Oxygenation in Patients with Pulmonary Vascular Disease Whilst Breathing Normobaric Hypoxia vs. Normoxia Before and After Sildenafil: Data from a Randomised Controlled Trial" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 23: 8407. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238407

APA StyleHäfliger, A., Furian, M., Schneider, S. R., Müller, J., Bauer, M., Carta, A. F., Schwarz, E. I., Saxer, S., Lichtblau, M., & Ulrich, S. (2025). Cerebral, Muscle and Blood Oxygenation in Patients with Pulmonary Vascular Disease Whilst Breathing Normobaric Hypoxia vs. Normoxia Before and After Sildenafil: Data from a Randomised Controlled Trial. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(23), 8407. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238407