Therapeutic Outcomes of Combined Eyelid Hygiene, Intense Pulsed Light, and Meibomian Gland Expression in Meibomian Gland Dysfunction

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Ethical Statement

2.2. Patients

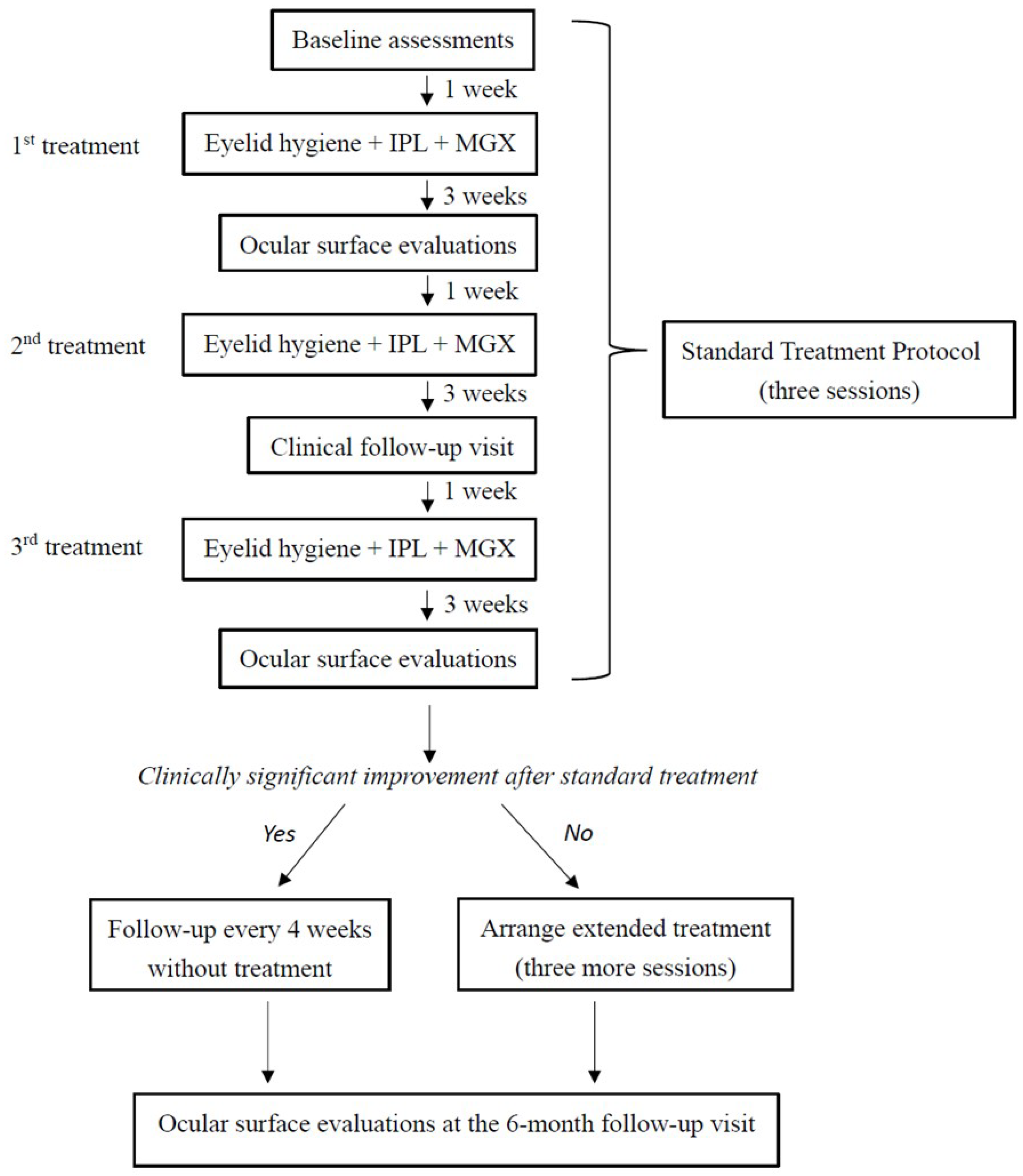

2.3. Experimental Design

2.4. Clinical Assessments

2.5. Combined Treatment with Eyelid Hygiene, IPL, and MGX

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ADES | Asia Dry Eye Society |

| DED | Dry Eye Disease |

| IPL | Intense Pulsed Light |

| MGD | Meibomian Gland Dysfunction |

| MGE | Meibomian Gland Expressibility |

| MGX | Meibomian Gland Expression |

| NIBUT | Noninvasive Tear Breakup Time |

| OSDI | Ocular Surface Disease Index |

| SAS | Statistical Analysis Software |

| TFOS DEWS II | Tear Film and Ocular Surface Society Dry Eye Workshop II |

| TMH | Tear Meniscus Height |

References

- Tavares, F.P.; Fernandes, R.S.; Bernardes, T.F.; Bonfioli, A.A.; Soares, E.J. Dry eye disease. Semin. Ophthalmol. 2010, 25, 84–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tashbayev, B.; Yazdani, M.; Arita, R.; Fineide, F.; Utheim, T.P. Intense pulsed light treatment in meibomian gland dysfunction: A concise review. Ocul. Surf. 2020, 18, 583–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craig, J.P.; Nichols, K.K.; Akpek, E.K.; Caffery, B.; Dua, H.S.; Joo, C.K.; Liu, Z.; Nelson, J.D.; Nichols, J.J.; Tsubota, K.; et al. TFOS DEWS II Definition and Classification Report. Ocul. Surf. 2017, 15, 276–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolffsohn, J.S.; Benítez-Del-Castillo, J.M.; Loya-Garcia, D.; Inomata, T.; Iyer, G.; Liang, L.; Pult, H.; Sabater, A.L.; Starr, C.E.; Vehof, J.; et al. TFOS DEWS III: Diagnostic Methodology. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 2025, 279, 387–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsubota, K.; Yokoi, N.; Shimazaki, J.; Watanabe, H.; Dogru, M.; Yamada, M.; Kinoshita, S.; Kim, H.M.; Tchah, H.W.; Hyon, J.Y.; et al. New Perspectives on Dry Eye Definition and Diagnosis: A Consensus Report by the Asia Dry Eye Society. Ocul. Surf. 2017, 15, 65–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viso, E.; Gude, F.; Rodriguez-Ares, M.T. The association of meibomian gland dysfunction and other common ocular diseases with dry eye: A population-based study in Spain. Cornea 2011, 30, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tong, L.; Chaurasia, S.S.; Mehta, J.S.; Beuerman, R.W. Screening for meibomian gland disease: Its relation to dry eye subtypes and symptoms in a tertiary referral clinic in singapore. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2010, 51, 3449–3454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lemp, M.A.; Crews, L.A.; Bron, A.J.; Foulks, G.N.; Sullivan, B.D. Distribution of aqueous-deficient and evaporative dry eye in a clinic-based patient cohort: A retrospective study. Cornea 2012, 31, 472–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, J.D.; Shimazaki, J.; Benitez-del-Castillo, J.M.; Craig, J.P.; McCulley, J.P.; Den, S.; Foulks, G.N. The international workshop on meibomian gland dysfunction: Report of the definition and classification subcommittee. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2011, 52, 1930–1937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chhadva, P.; Goldhardt, R.; Galor, A. Meibomian Gland Disease: The Role of Gland Dysfunction in Dry Eye Disease. Ophthalmology 2017, 124, S20–S26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hassanzadeh, S.; Varmaghani, M.; Zarei-Ghanavati, S.; Shandiz, J.H.; Khorasani, A.A. Global Prevalence of Meibomian Gland Dysfunction: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Ocul. Immunol. Inflamm. 2021, 29, 66–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moreno, I.; Verma, S.; Gesteira, T.F.; Thomas, V.J.C. Recent advances in age-related meibomian gland dysfunction (ARMGD). Ocul. Surf. 2023, 30, 298–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nichols, K.K.; Foulks, G.N.; Bron, A.J.; Glasgow, B.J.; Dogru, M.; Tsubota, K.; Lemp, M.A.; Sullivan, D.A. The international workshop on meibomian gland dysfunction: Executive summary. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2011, 52, 1922–1929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amano, S.; Shimazaki, J.; Yokoi, N.; Hori, Y.; Arita, R. Meibomian Gland Dysfunction Clinical Practice Guidelines. Jpn. J. Ophthalmol. 2023, 67, 448–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabeti, S.; Kheirkhah, A.; Yin, J.; Dana, R. Management of meibomian gland dysfunction: A review. Surv. Ophthalmol. 2020, 65, 205–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villani, E.; Marelli, L.; Dellavalle, A.; Serafino, M.; Nucci, P. Latest evidences on meibomian gland dysfunction diagnosis and management. Ocul. Surf. 2020, 18, 871–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arita, R.; Fukuoka, S. Non-pharmaceutical treatment options for meibomian gland dysfunction. Clin. Exp. Optom. 2020, 103, 742–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maskin, S.L. Intraductal meibomian gland probing relieves symptoms of obstructive meibomian gland dysfunction. Cornea 2010, 29, 1145–1152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greiner, J.V. A single LipiFlow® Thermal Pulsation System treatment improves meibomian gland function and reduces dry eye symptoms for 9 months. Curr. Eye Res. 2012, 37, 272–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Husain, Z.; Alster, T.S. The role of lasers and intense pulsed light technology in dermatology. Clin. Cosmet. Investig. Dermatol. 2016, 9, 29–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wat, H.; Wu, D.C.; Rao, J.; Goldman, M.P. Application of intense pulsed light in the treatment of dermatologic disease: A systematic review. Dermatol. Surg. 2014, 40, 359–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raulin, C.; Greve, B.; Grema, H. IPL technology: A review. Lasers Surg. Med. 2003, 32, 78–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toyos, R.; McGill, W.; Briscoe, D. Intense pulsed light treatment for dry eye disease due to meibomian gland dysfunction; a 3-year retrospective study. Photomed. Laser Surg. 2015, 33, 41–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, X.; Lv, H.; Song, H.; Zhang, M.; Liu, Y.; Hu, X.; Li, X.; Wang, W. Evaluation of the Safety and Effectiveness of Intense Pulsed Light in the Treatment of Meibomian Gland Dysfunction. J. Ophthalmol. 2016, 2016, 1910694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Narang, P.; Donthineni, P.R.; D’Souza, S.; Basu, S. Evaporative dry eye disease due to meibomian gland dysfunction: Preferred practice pattern guidelines for diagnosis and treatment. Indian J. Ophthalmol. 2023, 71, 1348–1356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, P.K.; Vora, G.K.; Matossian, C.; Kim, M.; Stinnett, S. Outcomes of intense pulsed light therapy for treatment of evaporative dry eye disease. Can. J. Ophthalmol. 2016, 51, 249–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vegunta, S.; Patel, D.; Shen, J.F. Combination Therapy of Intense Pulsed Light Therapy and Meibomian Gland Expression (IPL/MGX) Can Improve Dry Eye Symptoms and Meibomian Gland Function in Patients with Refractory Dry Eye: A Retrospective Analysis. Cornea 2016, 35, 318–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dell, S.J.; Gaster, R.N.; Barbarino, S.C.; Cunningham, D.N. Prospective evaluation of intense pulsed light and meibomian gland expression efficacy on relieving signs and symptoms of dry eye disease due to meibomian gland dysfunction. Clin. Ophthalmol. 2017, 11, 817–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rong, B.; Tang, Y.; Tu, P.; Liu, R.; Qiao, J.; Song, W.; Toyos, R.; Yan, X. Intense Pulsed Light Applied Directly on Eyelids Combined with Meibomian Gland Expression to Treat Meibomian Gland Dysfunction. Photomed. Laser Surg. 2018, 36, 326–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srinivasan, S.; Menzies, K.; Sorbara, L.; Jones, L. Infrared imaging of meibomian gland structure using a novel keratograph. Optom. Vis. Sci. 2012, 89, 788–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, J.; Adil, M.Y.; Chen, X.; Utheim, O.A.; Raeder, S.; Tonseth, K.A.; Lagali, N.S.; Dartt, D.A.; Utheim, T.P. Functional and Morphological Evaluation of Meibomian Glands in the Assessment of Meibomian Gland Dysfunction Subtype and Severity. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 2020, 209, 160–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maguire, M.G.; Asbell, P.A.; Group, D.S.R. n-3 Fatty Acid Supplementation and Dry Eye Disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 2018, 379, 691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arita, R.; Morishige, N.; Koh, S.; Shirakawa, R.; Kawashima, M.; Sakimoto, T.; Suzuki, T.; Tsubota, K. Increased Tear Fluid Production as a Compensatory Response to Meibomian Gland Loss: A Multicenter Cross-sectional Study. Ophthalmology 2015, 122, 925–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Straatsma, B.R. Cystic degeneration of the meibomian glands. AMA Arch. Ophthalmol. 1959, 61, 918–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schiffman, R.M.; Christianson, M.D.; Jacobsen, G.; Hirsch, J.D.; Reis, B.L. Reliability and validity of the Ocular Surface Disease Index. Arch. Ophthalmol. 2000, 118, 615–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bron, A.J.; Evans, V.E.; Smith, J.A. Grading of corneal and conjunctival staining in the context of other dry eye tests. Cornea 2003, 22, 640–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arita, R.; Minoura, I.; Morishige, N.; Shirakawa, R.; Fukuoka, S.; Asai, K.; Goto, T.; Imanaka, T.; Nakamura, M. Development of Definitive and Reliable Grading Scales for Meibomian Gland Dysfunction. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 2016, 169, 125–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dell, S.J. Intense pulsed light for evaporative dry eye disease. Clin. Ophthalmol. 2017, 11, 1167–1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, R.; Rong, B.; Tu, P.; Tang, Y.; Song, W.; Toyos, R.; Toyos, M.; Yan, X. Analysis of Cytokine Levels in Tears and Clinical Correlations After Intense Pulsed Light Treating Meibomian Gland Dysfunction. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 2017, 183, 81–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, S.H.; Kim, M.; Lee, W.J.; Chun, Y.S.; Kim, K.W. Different Number of Sessions of Intense Pulsed Light and Meibomian Gland Expression Combination Therapy for Meibomian Gland Dysfunction. Korean J. Ophthalmol. 2022, 36, 527–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Gong, L.; Yin, Y. Need to Increase the Number of Intense Pulsed Light (IPL) Treatment Sessions for Patients with Moderate to Severe Meibomian Gland Dysfunction (MGD) Patients. Curr. Eye Res. 2024, 49, 362–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sullivan, D.A.; Rocha, E.M.; Aragona, P.; Clayton, J.A.; Ding, J.; Golebiowski, B.; Hampel, U.; McDermott, A.M.; Schaumberg, D.A.; Srinivasan, S.; et al. TFOS DEWS II Sex, Gender, and Hormones Report. Ocul. Surf. 2017, 15, 284–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stapleton, F.; Argüeso, P.; Asbell, P.; Azar, D.; Bosworth, C.; Chen, W.; Ciolino, J.B.; Craig, J.P.; Gallar, J.; Galor, A.; et al. TFOS DEWS III: Digest. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 2025, 279, 451–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Category | Criteria |

|---|---|

| Inclusion criteria |

|

| Exclusion criteria |

|

| Parameter | Overall N = 107 | Standard Treatment Group N = 74 | Extended Treatment Group N = 33 | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 30 (28.0) | 20 (27.0) | 10 (30.3) | 0.728 |

| Female | 77 (72.0) | 54 (73.0) | 23 (69.7) | |

| Age | 64.3 ± 10.88 (21–85) | 65.3 ± 9.17 (32–81) | 62.0 ± 13.87 (21–85) | 0.302 |

| OSDI | 38.1 ± 27.75 (0–100) | 37.2 ± 28.42 (0–100) | 40.3 ± 26.47 (0–100) | 0.463 |

| NIBUT | 11.5 ± 5.10 (0–22.1) | 11.8 ± 4.98 (2.9–22.1) | 10.8 ± 5.38 (0–19.0) | 0.339 |

| TMH | 0.20 ± 0.12 (0.06–0.75) | 0.21 ± 0.12 (0.06–0.75) | 0.18 ± 0.11 (0.06–0.62) | 0.144 |

| Conjunctival redness | 14 ± 0.52 (0.4–2.9) | 1.4 ± 0.41 (0.7–2.8) | 1.6 ± 0.69 (0.4–2.9) | 0.313 |

| Corneal staining | 1 (0–1) | 1 (0–1) | 0 (0–1) | 0.196 |

| Conjunctival staining | 1 (0–1) | 1 (0–2) | 0.5 (0–1) | 0.564 |

| Plugging | 3 (2–3) | 3 (2–3) | 3 (2–3) | 0.497 |

| Telangiectasia | 3 (2–3) | 3 (2–3) | 3 (2–3) | 0.752 |

| Thickness | 1 (1–2) | 1 (1–2) | 1 (1–1) | 0.031 * |

| Irregularity | 1 (1–2) | 1 (1–2) | 1 (1–2) | 0.406 |

| MGE | 21 (19–24) | 21 (18–24) | 22 (20–24) | 0.512 |

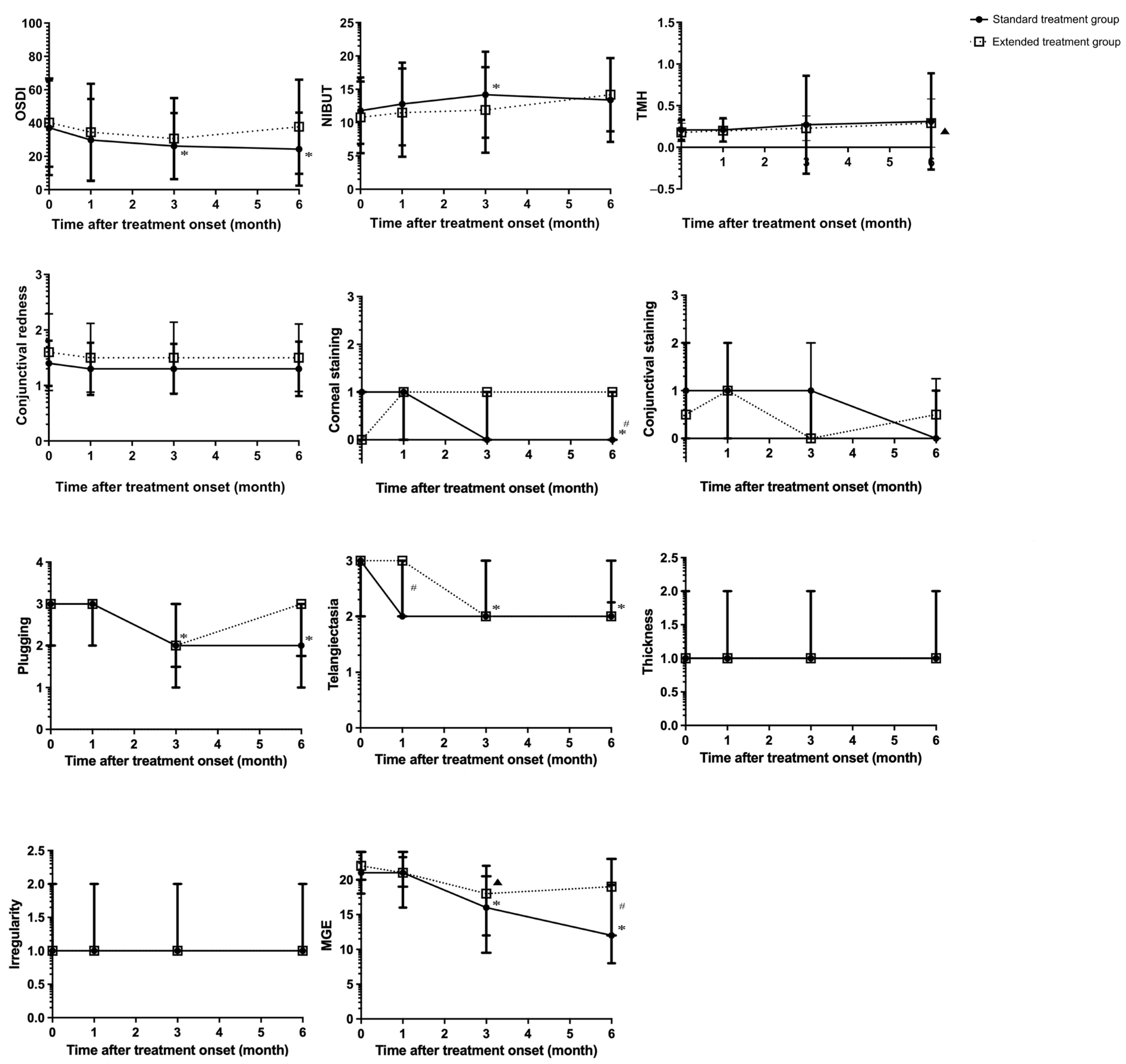

| Parameter | Group | Baseline | 1 Month After Treatment | 3 Months After Treatment | 6 Months After Treatment | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| p-Value † | Overall p-Value # | p-Value † | p-Value ‡ | p-Value † | p-Value ‡ | p-Value † | p-Value ‡ | ||||||

| OSDI | Standard | 37.2 ± 28.42 | 0.463 | <0.001 * | 29.9 ± 24.60 | 0.679 | 0.173 | 26.2 ± 19.81 | 0.714 | 0.004 § | 24.4 ± 21.95 | 0.2857 | 0.001 § |

| Extended | 40.3 ± 26.47 | 0.291 | 34.5 ± 29.13 | 0.252 | 30.7 ± 24.38 | 0.53 | 37.8 ± 28.25 | 1.000 | |||||

| NIBUT | Standard | 11.8 ± 4.98 | 0.339 | 0.008 * | 12.8 ± 6.21 | 0.409 | 0.732 | 14.2 ± 6.46 | 0.302 | 0.006 § | 13.4 ± 6.30 | 0.5970 | 0.260 |

| Extended | 10.8 ± 5.38 | 0.077 | 11.5 ± 6.64 | 1.000 | 11.9 ± 6.42 | 1.000 | 14.2 ± 5.50 | 0.453 | |||||

| TMH | Standard | 0.21 ± 0.12 | 0.144 | 0.192 | 0.21 ± 0.14 | 0.461 | 1.000 | 0.27 ± 0.59 | 0.466 | 1.000 | 0.31 ± 0.58 | 0.4477 | 0.654 |

| Extended | 0.18 ± 0.11 | 0.137 | 0.20 ± 0.14 | 1.000 | 0.23 ± 0.15 | 1.000 | 0.29 ± 0.29 | 0.594 | |||||

| Conjunctival redness | Standard | 1.4 ± 0.41 | 0.313 | 0.067 | 1.3 ± 0.47 | 0.945 | 1.000 | 1.3 ± 0.45 | 0.637 | 0.315 | 1.3 ± 0.49 | 0.429 | 0.103 |

| Extended | 1.6 ± 0.69 | 0.131 | 1.5 ± 0.62 | 1.000 | 1.5 ± 0.64 | 0.282 | 1.5 ± 0.61 | 0.642 | |||||

| Corneal staining | Standard | 1 (0–1) | 0.196 | <0.001 * | 1 (0–1) | 0.366 | 1.000 | 0 (0–1) | 0.173 | 0.023 | 0 (0–1) | 0.014 * | <0.001 § |

| Extended | 0 (0–1) | 0.658 | 1 (0–1) | 1.000 | 1 (0–1) | 0.99 | 1 (0–1) | 1.000 | |||||

| Conjunctival staining | Standard | 1 (0–2) | 0.564 | 0.568 | 1 (0–2) | 0.964 | 1.000 | 1 (0–1) | 0.795 | 1.000 | 0 (0–1) | 0.591 | 0.434 |

| Extended | 0.5 (0–1) | 0.908 | 1 (0–1) | 0.888 | 0 (0–2) | 1.000 | 0.5 (0–1.25) | 1.000 | |||||

| Plugging | Standard | 3 (2–3) | 0.497 | <0.001 * | 3 (2–3) | 0.062 | 1.000 | 2 (1–3) | 0.823 | <0.001 § | 2 (1–3) | 0.092 | <0.001§ |

| Extended | 3 (2–3) | 0.159 | 3 (3–3) | 0.745 | 2 (1.5–3) | 0.05 | 3 (1.75–3) | 0.569 | |||||

| Telangiectasia | Standard | 3 (2–3) | 0.752 | <0.001 * | 2 (2–3) | 0.021 * | 0.443 | 2 (2–3) | 0.311 | 0.003 § | 2 (2–2.25) | 0.124 | <0.001 § |

| Extended | 3 (2–3) | 0.073 | 3 (2–3) | 1.000 | 2 (2–3) | 0.178 | 2 (2–3) | 0.319 | |||||

| Thickness | Standard | 1 (1–2) | 0.031 * | 0.322 | 1 (1–2) | 0.061 | 0.143 | 1 (1–2) | 0.895 | 1.000 | 1 (1–2) | 0.317 | 1.000 |

| Extended | 1 (1–1) | 0.039 * | 1 (1–2) | 0.25 | 1 (1–2) | 0.066 | 1 (1–2) | 0.038 | |||||

| Irregularity | Standard | 1 (1–2) | 0.406 | 0.308 | 1 (1–2) | 0.572 | 0.182 | 1 (1–2) | 0.713 | 1.000 | 1 (1–2) | 0.583 | 1.000 |

| Extended | 1 (1–2) | 0.974 | 1 (1–2) | 1.000 | 1 (1–2) | 1.000 | 1 (1–2) | 1.000 | |||||

| MGE | Standard | 21 (18–24) | 0.512 | <0.001 * | 21 (16–23.25) | 0.574 | 0.055 | 16 (12–22) | 0.672 | <0.001 § | 12 (8–19.25) | 0.013 * | <0.001 § |

| Extended | 22 (20–24) | 0.036 * | 21 (19–24) | 0.371 | 18 (9.5–20.5) | <0.001 § | 19 (12–23) | 0.041 | |||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chien, C.-C.; Chang, Y.-M.; Liang, C.-M.; Chien, K.-H.; Tai, M.-C.; Lin, T.-Y.; Weng, T.-H. Therapeutic Outcomes of Combined Eyelid Hygiene, Intense Pulsed Light, and Meibomian Gland Expression in Meibomian Gland Dysfunction. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 8406. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238406

Chien C-C, Chang Y-M, Liang C-M, Chien K-H, Tai M-C, Lin T-Y, Weng T-H. Therapeutic Outcomes of Combined Eyelid Hygiene, Intense Pulsed Light, and Meibomian Gland Expression in Meibomian Gland Dysfunction. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(23):8406. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238406

Chicago/Turabian StyleChien, Chien-Cheng, Yu-Min Chang, Chang-Min Liang, Ke-Hung Chien, Ming-Cheng Tai, Ting-Yi Lin, and Tzu-Heng Weng. 2025. "Therapeutic Outcomes of Combined Eyelid Hygiene, Intense Pulsed Light, and Meibomian Gland Expression in Meibomian Gland Dysfunction" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 23: 8406. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238406

APA StyleChien, C.-C., Chang, Y.-M., Liang, C.-M., Chien, K.-H., Tai, M.-C., Lin, T.-Y., & Weng, T.-H. (2025). Therapeutic Outcomes of Combined Eyelid Hygiene, Intense Pulsed Light, and Meibomian Gland Expression in Meibomian Gland Dysfunction. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(23), 8406. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238406