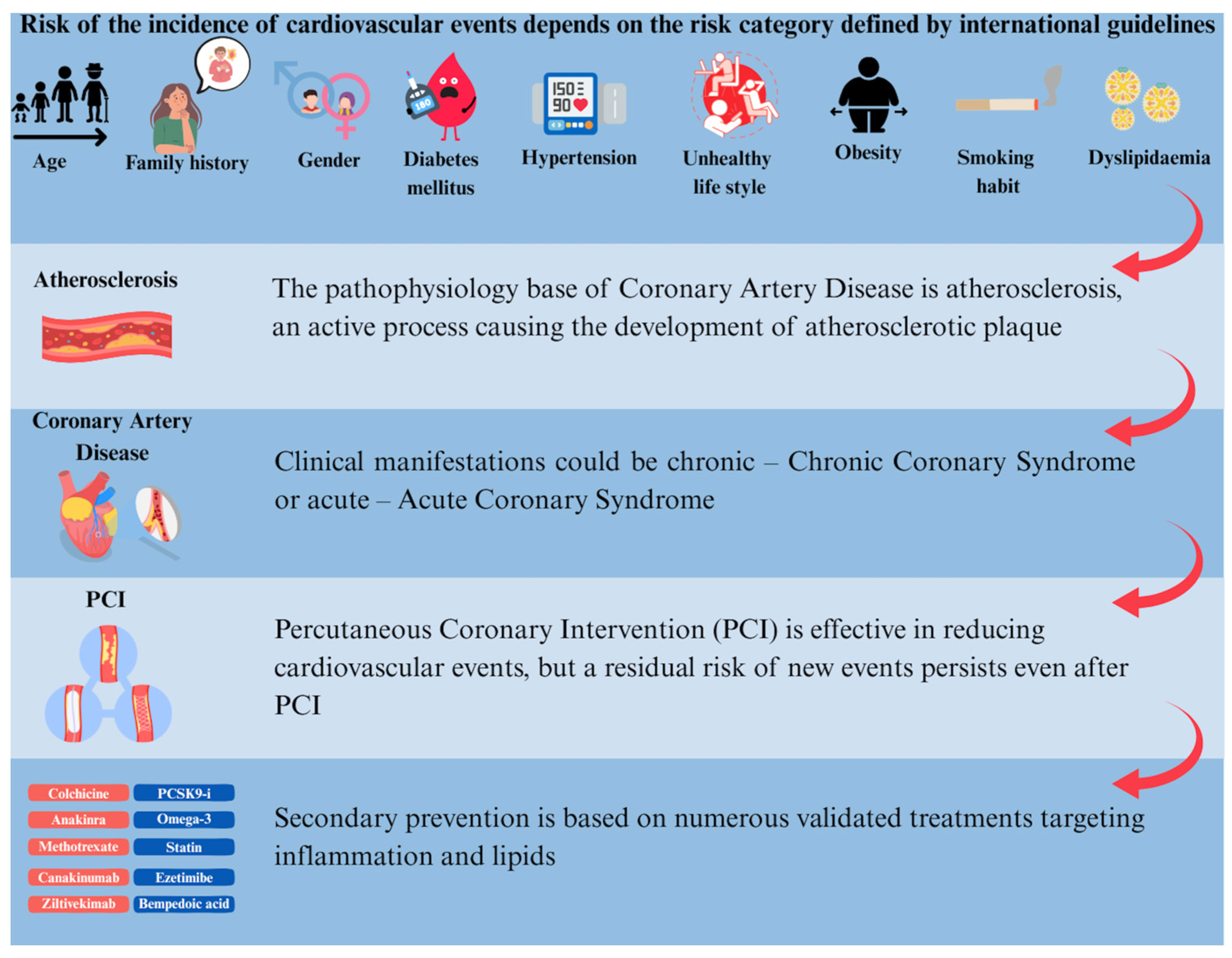

Optimal Medical Therapy Targeting Lipids and Inflammation for Secondary Prevention in Patients Undergoing Percutaneous Coronary Intervention

Abstract

1. Introduction

Residual Cardiovascular Risk

2. Pathophysiology

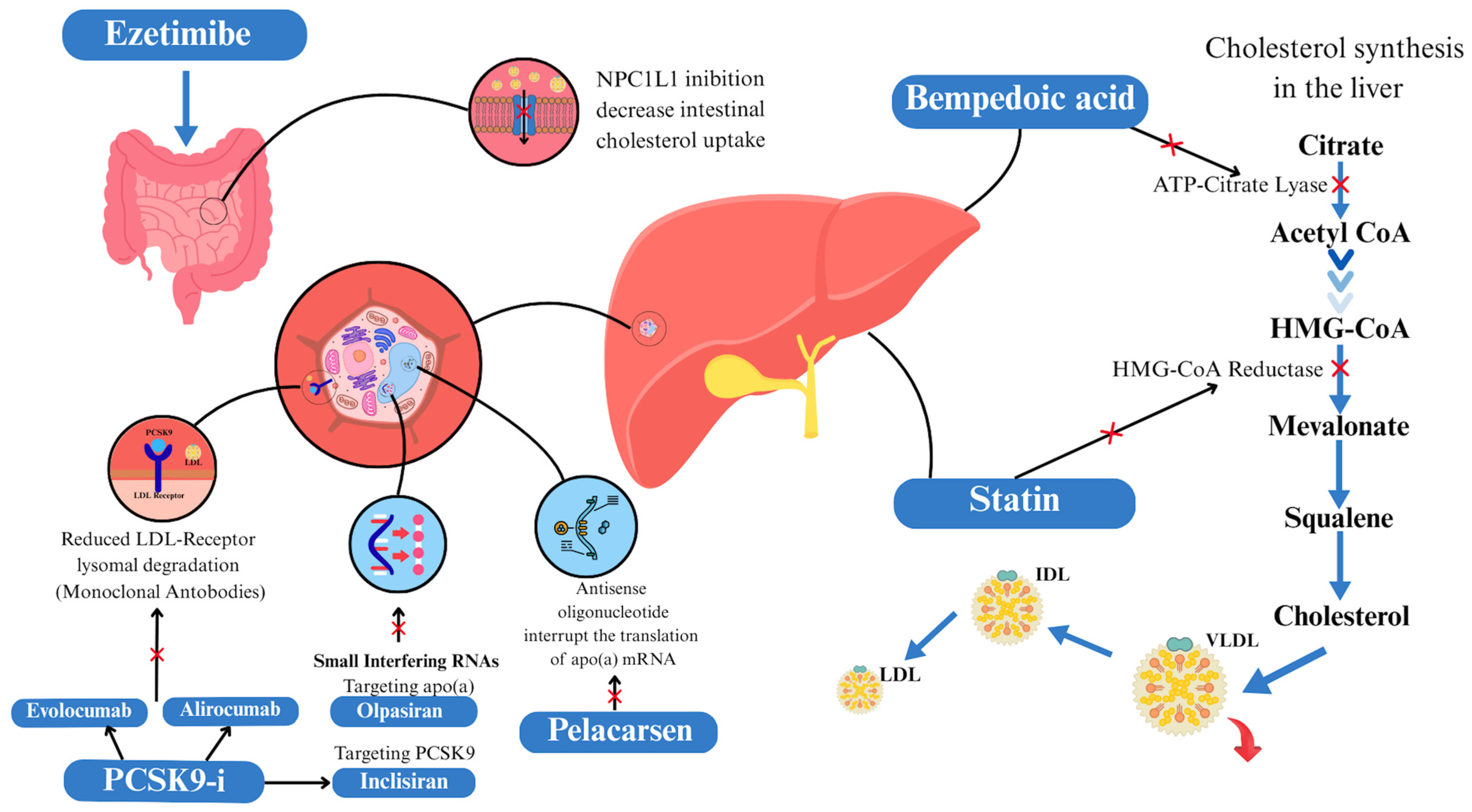

2.1. Pathophysiology of Lipids

2.2. Pathophysiology of Inflammation

3. Secondary Prevention

3.1. Targeting Lipids

3.1.1. Statin, Ezetimibe, and Combination Therapy

3.1.2. Proprotein Convertase Subtilisin/Kexin Type 9 Inhibitors

3.1.3. Bempedoic Acid

3.1.4. Obicetrapib

3.1.5. Omega-3 Fatty Acids and Icosapent Ethyl

3.1.6. Lipoprotein(a)

3.2. Targeting Inflammation

3.2.1. Colchicine

3.2.2. Methotrexate

3.2.3. Canakinumab

3.2.4. Ziltivekimab, Anakinra, Goflikicept

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AA | Arachidonic Acid |

| ACC | American College of Cardiology |

| ACS | Acute Coronary Syndrome |

| AGE | Advanced Glycation End products |

| AHA | American Heart Association |

| ASCVD | Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Disease |

| BMI | Body Mass Index |

| CAD | Coronary Artery Disease |

| CABG | Coronary Artery Bypass Graft |

| CCS | Chronic Coronary Syndrome |

| CETP | Cholesteryl Ester Transfer Protein |

| CI | Confidence Interval |

| CPK-MB | Creatine Kinase-Myocardial brain fraction |

| CV | Cardiovascular |

| CVD | Cardiovascular Disease |

| DES | Drug Eluting Stent |

| EAS | European Atherosclerosis Society |

| eLDL-TG | Estimating Low-Density Lipoprotein-Triglycerides |

| EPA | Eicosapentaenoic Acid |

| ESC | European Society of Cardiology |

| FFAs | Free Fatty Acids |

| FPG | Fasting Plasma Glucose |

| GDMT | Guideline Directed Medical Therapy |

| GISE | Italian Society of Interventional Cardiology |

| HbA1c | Glycated Hemoglobin |

| HDL | High-Density Lipoprotein |

| HeFH | Heterozygous familial hypercholesterolemia |

| HMG Co-A | Hydroxymethylglutaryl-CoA |

| HoFH | Homozygous Familial Hypercholesterolemia |

| HR | Hazard Ratio |

| Hs-CRP | High-sensitivity C-Reactive Protein |

| ICAM-1 | Intercellular Adhesion Molecule-1 |

| IDL | Intermediate-Density Lipoprotein |

| IL | Interleukin |

| IPE | Icosapent Ethyl |

| IQR | Interquartile range |

| IS | Infarct Size |

| IVUS | Intravascular Ultrasound |

| LDE-MTX | Lipid Nanoemulsion-Methotrexate |

| LDL-C | Low-Density Lipoprotein |

| LDL-R | Low-Density Lipoprotein Receptors |

| LLT | Lipid-Lowering Therapy |

| LPL | Lipoprotein Lipase |

| Lp(a) | Lipoprotein A |

| LVR | Left Ventricular Remodeling |

| MACE | Major Adverse Cardiovascular Event |

| MCP | Monocyte Chemotactic Protein |

| MI | Myocardial Infarction |

| MMP | Matrix Metalloproteinases |

| MTX | Methotrexate |

| NADH/NADPH | Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide reduced form/Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate reduced |

| NET | Neutrophil Extracellular Traps |

| NIRS | Near-Infrared Spectroscopy |

| NLRP3 | NACHT, LRR and PYD domains-containing protein 3 |

| NPC1L1 | Niemann-Pick C1-like protein 1 |

| NSTEMI | No-ST-up Elevation Myocardial Infarction |

| NYHA | New York Heart Association |

| OCT | Optical Coherence Tomography |

| OGTT | Oral Glucose Tolerance Test |

| OMT | Optimal Medical Therapy |

| OR | Odds Ratio |

| PAI | Plasma fibrinogen Activator Inhibitor |

| PCI | Percutaneous Coronary Intervention |

| PCSK9-i | Proprotein Convertase Subtilisin/Kexin type 9 Inhibitor |

| PUFA | Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids |

| ROS | Reactive Oxygen Species |

| RR | Relative Risk |

| SIL2r | Soluble IL-2 receptor |

| SMCs | Smooth Muscle Cells |

| STEMI | ST-up Elevation Myocardial Infarction |

| T2DM | Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus |

| TG | Triglycerides |

| TGRLs | Triglyceride-Rich Lipoproteins |

| TNF | Tumor Necrosis Factor |

| TyG | Triglyceride-Glucose |

| VCAM-1 | Vascular Cell Adhesion Molecule-1 |

| VLDL | Very-Low-Density Lipoprotein |

References

- Gill, P.; Uthman, O.A.; Alam, K.; GBD 2017 Causes of Death Collaborators. Global, Regional, and National Age-Sex-Specific Mortality for 282 Causes of Death in 195 Countries and Territories, 1980–2017: A Systematic Analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet 2018, 392, 1736–1788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawler, P.R.; Bhatt, D.L.; Godoy, L.C.; Lüscher, T.F.; Bonow, R.O.; Verma, S.; Ridker, P.M. Targeting Cardiovascular Inflammation: Next Steps in Clinical Translation. Eur. Heart J. 2021, 42, 113–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mach, F.; Koskinas, K.C.; Roeters van Lennep, J.E.; Tokgözoğlu, L.; Badimon, L.; Baigent, C.; Benn, M.; Binder, C.J.; Catapano, A.L.; De Backer, G.G.; et al. 2025 Focused Update of the 2019 ESC/EAS Guidelines for the Management of Dyslipidaemias. Eur. Heart J. 2025, 46, 4359–4378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vrints, C.; Andreotti, F.; Koskinas, K.C.; Rossello, X.; Adamo, M.; Ainslie, J.; Banning, A.P.; Budaj, A.; Buechel, R.R.; Chiariello, G.A.; et al. 2024 ESC Guidelines for the Management of Chronic Coronary Syndromes. Eur. Heart J. 2024, 45, 3415–3537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maron, D.J.; Hochman, J.S.; Reynolds, H.R.; Bangalore, S.; O’Brien, S.M.; Boden, W.E.; Chaitman, B.R.; Senior, R.; López-Sendón, J.; Alexander, K.P.; et al. Initial Invasive or Conservative Strategy for Stable Coronary Disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 382, 1395–1407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boden, W.E.; O’Rourke, R.A.; Teo, K.K.; Hartigan, P.M.; Maron, D.J.; Kostuk, W.J.; Knudtson, M.; Dada, M.; Casperson, P.; Harris, C.L.; et al. Optimal Medical Therapy with or without PCI for Stable Coronary Disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 2007, 356, 1503–1516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Bruyne, B.; Pijls, N.H.J.; Kalesan, B.; Barbato, E.; Tonino, P.A.L.; Piroth, Z.; Jagic, N.; Möbius-Winkler, S.; Rioufol, G.; Witt, N.; et al. Fractional Flow Reserve-Guided PCI versus Medical Therapy in Stable Coronary Disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 2012, 367, 991–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spertus, J.A.; Jones, P.G.; Maron, D.J.; O’Brien, S.M.; Reynolds, H.R.; Rosenberg, Y.; Stone, G.W.; Harrell, F.E.; Boden, W.E.; Weintraub, W.S.; et al. Health-Status Outcomes with Invasive or Conservative Care in Coronary Disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 382, 1408–1419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velazquez, E.J.; Lee, K.L.; Deja, M.A.; Jain, A.; Sopko, G.; Marchenko, A.; Ali, I.S.; Pohost, G.; Gradinac, S.; Abraham, W.T.; et al. Coronary-Artery Bypass Surgery in Patients with Left Ventricular Dysfunction. N. Engl. J. Med. 2011, 364, 1607–1616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hochman, J.S.; Anthopolos, R.; Reynolds, H.R.; Bangalore, S.; Xu, Y.; O’Brien, S.M.; Mavromichalis, S.; Chang, M.; Contreras, A.; Rosenberg, Y.; et al. Survival After Invasive or Conservative Management of Stable Coronary Disease. Circulation 2023, 147, 8–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilardi, F.; Ferrone, M.; Avvedimento, M.; Servillo, G.; Gargiulo, G. Complete Revascularization in Acute and Chronic Coronary Syndrome. Cardiol. Clin. 2020, 38, 491–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne, R.A.; Rossello, X.; Coughlan, J.J.; Barbato, E.; Berry, C.; Chieffo, A.; Claeys, M.J.; Dan, G.-A.; Dweck, M.R.; Galbraith, M.; et al. 2023 ESC Guidelines for the Management of Acute Coronary Syndromes. Eur. Heart J. 2023, 44, 3720–3826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, S.V.; O’Donoghue, M.L.; Ruel, M.; Rab, T.; Tamis-Holland, J.E.; Alexander, J.H.; Baber, U.; Baker, H.; Cohen, M.G.; Cruz-Ruiz, M.; et al. 2025 ACC/AHA/ACEP/NAEMSP/SCAI Guideline for the Management of Patients With Acute Coronary Syndromes: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation 2025, 151, e771–e862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thuijs, D.J.F.M.; Kappetein, A.P.; Serruys, P.W.; Mohr, F.-W.; Morice, M.-C.; Mack, M.J.; Holmes, D.R.; Curzen, N.; Davierwala, P.; Noack, T.; et al. Percutaneous Coronary Intervention versus Coronary Artery Bypass Grafting in Patients with Three-Vessel or Left Main Coronary Artery Disease: 10-Year Follow-up of the Multicentre Randomised Controlled SYNTAX Trial. Lancet 2019, 394, 1325–1334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Luca, L.; Di Fusco, S.A.; Iannopollo, G.; Mistrulli, R.; Rizzello, V.; Aimo, A.; Navazio, A.; Bilato, C.; Corda, M.; Di Marco, M.; et al. ANMCO Scientific statement on combination therapies and polypill in secondary prevention. G. Ital. Cardiol. 2006 2024, 25, 367–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mach, F.; Baigent, C.; Catapano, A.L.; Koskinas, K.C.; Casula, M.; Badimon, L.; Chapman, M.J.; De Backer, G.G.; Delgado, V.; Ference, B.A.; et al. 2019 ESC/EAS Guidelines for the Management of Dyslipidaemias: Lipid Modification to Reduce Cardiovascular Risk. Eur. Heart J. 2020, 41, 111–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomez-Delgado, F.; Raya-Cruz, M.; Katsiki, N.; Delgado-Lista, J.; Perez-Martinez, P. Residual Cardiovascular Risk: When Should We Treat It? Eur. J. Intern. Med. 2024, 120, 17–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gargiulo, G.; Piccolo, R.; Park, D.-W.; Nam, G.-B.; Okumura, Y.; Esposito, G.; Valgimigli, M. Single vs. Dual Antithrombotic Therapy in Patients with Oral Anticoagulation and Stabilized Coronary Artery Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized-Controlled Trials. J. Cardiovasc. Med. 2025, 26, 258–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castiello, D.S.; Buongiorno, F.; Manzi, L.; Narciso, V.; Forzano, I.; Florimonte, D.; Sperandeo, L.; Canonico, M.E.; Avvedimento, M.; Paolillo, R.; et al. Procedural and Antithrombotic Therapy Optimization in Patients with Atrial Fibrillation Undergoing Percutaneous Coronary Intervention: A Narrative Review. J. Cardiovasc. Dev. Dis. 2025, 12, 142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Canonico, M.E.; Avvedimento, M.; Piccolo, R.; Hess, C.N.; Bardi, L.; Ilardi, F.; Giugliano, G.; Franzone, A.; Gargiulo, G.; Berkowitz, S.D.; et al. Long-Term Antithrombotic Therapy in Patients With Chronic Coronary Syndrome: An Updated Review of Current Evidence. Clin. Ther. 2025, 47, 511–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galli, M.; Gragnano, F.; Berteotti, M.; Marcucci, R.; Gargiulo, G.; Calabrò, P.; Terracciano, F.; Andreotti, F.; Patti, G.; De Caterina, R.; et al. Antithrombotic Therapy in High Bleeding Risk, Part I: Percutaneous Cardiac Interventions. JACC Cardiovasc. Interv. 2024, 17, 2197–2215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manzi, L.; Florimonte, D.; Forzano, I.; Buongiorno, F.; Sperandeo, L.; Castiello, D.S.; Paolillo, R.; Giugliano, G.; Giacoppo, D.; Sciahbasi, A.; et al. Antiplatelet Therapy in Patients Requiring Oral Anticoagulation and Undergoing Percutaneous Coronary Intervention. Interv. Cardiol. Clin. 2024, 13, 527–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gargiulo, G.; Valgimigli, M.; Capodanno, D.; Bittl, J.A. State of the Art: Duration of Dual Antiplatelet Therapy after Percutaneous Coronary Intervention and Coronary Stent Implantation-Past, Present and Future Perspectives. EuroIntervention 2017, 13, 717–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giacoppo, D.; Matsuda, Y.; Fovino, L.N.; D’Amico, G.; Gargiulo, G.; Byrne, R.A.; Capodanno, D.; Valgimigli, M.; Mehran, R.; Tarantini, G. Short Dual Antiplatelet Therapy Followed by P2Y12 Inhibitor Monotherapy vs. Prolonged Dual Antiplatelet Therapy after Percutaneous Coronary Intervention with Second-Generation Drug-Eluting Stents: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Clinical Trials. Eur. Heart J. 2021, 42, 308–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gargiulo, G.; Windecker, S.; Vranckx, P.; Gibson, C.M.; Mehran, R.; Valgimigli, M. A Critical Appraisal of Aspirin in Secondary Prevention: Is Less More? Circulation 2016, 134, 1881–1906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capodanno, D.; Gargiulo, G.; Buccheri, S.; Giacoppo, D.; Capranzano, P.; Tamburino, C. Meta-Analyses of Dual Antiplatelet Therapy Following Drug-Eluting Stent Implantation: Do Bleeding and Stent Thrombosis Weigh Similar on Mortality? J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2015, 66, 1639–1640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giacoppo, D.; Gragnano, F.; Watanabe, H.; Kimura, T.; Kang, J.; Park, K.-W.; Kim, H.-S.; Pettersen, A.-Å.; Bhatt, D.L.; Pocock, S.; et al. P2Y12 Inhibitor or Aspirin after Percutaneous Coronary Intervention: Individual Patient Data Meta-Analysis of Randomised Clinical Trials. BMJ 2025, 389, e082561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faggioni, M.; Baber, U.; Sartori, S.; Giustino, G.; Cohen, D.J.; Henry, T.D.; Farhan, S.; Ariti, C.; Dangas, G.; Gibson, M.; et al. Incidence, Patterns, and Associations Between Dual-Antiplatelet Therapy Cessation and Risk for Adverse Events Among Patients With and Without Diabetes Mellitus Receiving Drug-Eluting Stents: Results From the PARIS Registry. JACC Cardiovasc. Interv. 2017, 10, 645–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bainey, K.R.; Welsh, R.C.; Connolly, S.J.; Marsden, T.; Bosch, J.; Fox, K.A.A.; Steg, P.G.; Vinereanu, D.; Connolly, D.L.; Berkowitz, S.D.; et al. Rivaroxaban Plus Aspirin Versus Aspirin Alone in Patients With Prior Percutaneous Coronary Intervention (COMPASS-PCI). Circulation 2020, 141, 1141–1151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wiviott, S.D.; Braunwald, E.; McCabe, C.H.; Montalescot, G.; Ruzyllo, W.; Gottlieb, S.; Neumann, F.-J.; Ardissino, D.; De Servi, S.; Murphy, S.A.; et al. Prasugrel versus Clopidogrel in Patients with Acute Coronary Syndromes. N. Engl. J. Med. 2007, 357, 2001–2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wallentin, L.; Becker, R.C.; Budaj, A.; Cannon, C.P.; Emanuelsson, H.; Held, C.; Horrow, J.; Husted, S.; James, S.; Katus, H.; et al. Ticagrelor versus Clopidogrel in Patients with Acute Coronary Syndromes. N. Engl. J. Med. 2009, 361, 1045–1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schüpke, S.; Neumann, F.-J.; Menichelli, M.; Mayer, K.; Bernlochner, I.; Wöhrle, J.; Richardt, G.; Liebetrau, C.; Witzenbichler, B.; Antoniucci, D.; et al. Ticagrelor or Prasugrel in Patients with Acute Coronary Syndromes. N. Engl. J. Med. 2019, 381, 1524–1534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bay, B.; Tanner, R.; Gao, M.; Oliva, A.; Sartori, S.; Vogel, B.; Gitto, M.; Smith, K.F.; Di Muro, F.M.; Hooda, A.; et al. Residual Cholesterol and Inflammatory Risk in Statin-Treated Patients Undergoing Percutaneous Coronary Intervention. Eur. Heart J. 2025, 46, 3167–3177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welsh, P.; Al Zabiby, A.; Byrne, H.; Benbow, H.R.; Itani, T.; Farries, G.; Costa-Scharplatz, M.; Ferber, P.; Martin, L.; Brown, R.; et al. Elevated Lipoprotein(a) Increases Risk of Subsequent Major Adverse Cardiovascular Events (MACE) and Coronary Revascularisation in Incident ASCVD Patients: A Cohort Study from the UK Biobank. Atherosclerosis 2024, 389, 117437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabatine, M.S.; Giugliano, R.P.; Keech, A.C.; Honarpour, N.; Wiviott, S.D.; Murphy, S.A.; Kuder, J.F.; Wang, H.; Liu, T.; Wasserman, S.M.; et al. Evolocumab and Clinical Outcomes in Patients with Cardiovascular Disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 2017, 376, 1713–1722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwartz, G.G.; Steg, P.G.; Szarek, M.; Bhatt, D.L.; Bittner, V.A.; Diaz, R.; Edelberg, J.M.; Goodman, S.G.; Hanotin, C.; Harrington, R.A.; et al. Alirocumab and Cardiovascular Outcomes after Acute Coronary Syndrome. N. Engl. J. Med. 2018, 379, 2097–2107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, K.V.; Pandey, A.; de Lemos, J.A. Conceptual Framework for Addressing Residual Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Disease Risk in the Era of Precision Medicine. Circulation 2018, 137, 2551–2553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ridker, P.M.; Everett, B.M.; Thuren, T.; MacFadyen, J.G.; Chang, W.H.; Ballantyne, C.; Fonseca, F.; Nicolau, J.; Koenig, W.; Anker, S.D.; et al. Antiinflammatory Therapy with Canakinumab for Atherosclerotic Disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 2017, 377, 1119–1131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ridker, P.M. Residual Inflammatory Risk: Addressing the Obverse Side of the Atherosclerosis Prevention Coin. Eur. Heart J. 2016, 37, 1720–1722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Luca, L.; Piscione, F.; Colivicchi, F.; Lucci, D.; Mascia, F.; Marinoni, B.; Cirillo, P.; Grosseto, D.; Mauro, C.; Calabrò, P.; et al. Contemporary Management of Patients Referring to Cardiologists One to Three Years from a Myocardial Infarction: The EYESHOT Post-MI Study. Int. J. Cardiol. 2018, 273, 8–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yusuf, S.; Islam, S.; Chow, C.K.; Rangarajan, S.; Dagenais, G.; Diaz, R.; Gupta, R.; Kelishadi, R.; Iqbal, R.; Avezum, A.; et al. Use of Secondary Prevention Drugs for Cardiovascular Disease in the Community in High-Income, Middle-Income, and Low-Income Countries (the PURE Study): A Prospective Epidemiological Survey. Lancet 2011, 378, 1231–1243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komajda, M.; Cosentino, F.; Ferrari, R.; Kerneis, M.; Kosmachova, E.; Laroche, C.; Maggioni, A.P.; Rittger, H.; Steg, P.G.; Szwed, H.; et al. Profile and Treatment of Chronic Coronary Syndromes in European Society of Cardiology Member Countries: The ESC EORP CICD-LT Registry. Eur. J. Prev. Cardiol. 2021, 28, 432–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandel, N.S. Lipid Metabolism. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2021, 13, a040576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ference, B.A.; Ginsberg, H.N.; Graham, I.; Ray, K.K.; Packard, C.J.; Bruckert, E.; Hegele, R.A.; Krauss, R.M.; Raal, F.J.; Schunkert, H.; et al. Low-Density Lipoproteins Cause Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Disease. 1. Evidence from Genetic, Epidemiologic, and Clinical Studies. A Consensus Statement from the European Atherosclerosis Society Consensus Panel. Eur. Heart J. 2017, 38, 2459–2472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotseva, K.; De Backer, G.; De Bacquer, D.; Rydén, L.; Hoes, A.; Grobbee, D.; Maggioni, A.; Marques-Vidal, P.; Jennings, C.; Abreu, A.; et al. Lifestyle and Impact on Cardiovascular Risk Factor Control in Coronary Patients across 27 Countries: Results from the European Society of Cardiology ESC-EORP EUROASPIRE V Registry. Eur. J. Prev. Cardiol. 2019, 26, 824–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danchin, N.; Almahmeed, W.; Al-Rasadi, K.; Azuri, J.; Berrah, A.; Cuneo, C.A.; Karpov, Y.; Kaul, U.; Kayıkçıoğlu, M.; Mitchenko, O.; et al. Achievement of Low-Density Lipoprotein Cholesterol Goals in 18 Countries Outside Western Europe: The International ChoLesterol Management Practice Study (ICLPS). Eur. J. Prev. Cardiol. 2018, 25, 1087–1094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stock, J.K. DA VINCI Study: Change in Approach to Cholesterol Management Will Be Needed to Reduce the Implementation Gap between Guidelines and Clinical Practice in Europe. Atherosclerosis 2020, 314, 74–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rader, D.J.; Hovingh, G.K. HDL and Cardiovascular Disease. Lancet 2014, 384, 618–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- REVEAL Collaborative Group; Bowman, L.; Chen, F.; Sammons, E.; Hopewell, J.C.; Wallendszus, K.; Stevens, W.; Valdes-Marquez, E.; Wiviott, S.; Cannon, C.P.; et al. Randomized Evaluation of the Effects of Anacetrapib through Lipid-Modification (REVEAL)-A Large-Scale, Randomized, Placebo-Controlled Trial of the Clinical Effects of Anacetrapib among People with Established Vascular Disease: Trial Design, Recruitment, and Baseline Characteristics. Am. Heart J. 2017, 187, 182–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AIM-HIGH Investigators; Boden, W.E.; Probstfield, J.L.; Anderson, T.; Chaitman, B.R.; Desvignes-Nickens, P.; Koprowicz, K.; McBride, R.; Teo, K.; Weintraub, W. Niacin in Patients with Low HDL Cholesterol Levels Receiving Intensive Statin Therapy. N. Engl. J. Med. 2011, 365, 2255–2267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenson, R.S.; Davidson, M.H.; Hirsh, B.J.; Kathiresan, S.; Gaudet, D. Genetics and Causality of Triglyceride-Rich Lipoproteins in Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Disease. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2014, 64, 2525–2540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nordestgaard, B.G.; Varbo, A. Triglycerides and Cardiovascular Disease. Lancet 2014, 384, 626–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ference, B.A.; Kastelein, J.J.P.; Ray, K.K.; Ginsberg, H.N.; Chapman, M.J.; Packard, C.J.; Laufs, U.; Oliver-Williams, C.; Wood, A.M.; Butterworth, A.S.; et al. Association of Triglyceride-Lowering LPL Variants and LDL-C-Lowering LDLR Variants With Risk of Coronary Heart Disease. JAMA 2019, 321, 364–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nordestgaard, B.G.; Langsted, A. Lipoprotein (a) as a Cause of Cardiovascular Disease: Insights from Epidemiology, Genetics, and Biology. J. Lipid Res. 2016, 57, 1953–1975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Valk, F.M.; Bekkering, S.; Kroon, J.; Yeang, C.; Van den Bossche, J.; van Buul, J.D.; Ravandi, A.; Nederveen, A.J.; Verberne, H.J.; Scipione, C.; et al. Oxidized Phospholipids on Lipoprotein(a) Elicit Arterial Wall Inflammation and an Inflammatory Monocyte Response in Humans. Circulation 2016, 134, 611–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgess, S.; Ference, B.A.; Staley, J.R.; Freitag, D.F.; Mason, A.M.; Nielsen, S.F.; Willeit, P.; Young, R.; Surendran, P.; Karthikeyan, S.; et al. Association of LPA Variants With Risk of Coronary Disease and the Implications for Lipoprotein(a)-Lowering Therapies: A Mendelian Randomization Analysis. JAMA Cardiol. 2018, 3, 619–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Donoghue, M.L.; Fazio, S.; Giugliano, R.P.; Stroes, E.S.G.; Kanevsky, E.; Gouni-Berthold, I.; Im, K.; Lira Pineda, A.; Wasserman, S.M.; Češka, R.; et al. Lipoprotein(a), PCSK9 Inhibition, and Cardiovascular Risk. Circulation 2019, 139, 1483–1492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visseren, F.L.J.; Mach, F.; Smulders, Y.M.; Carballo, D.; Koskinas, K.C.; Bäck, M.; Benetos, A.; Biffi, A.; Boavida, J.-M.; Capodanno, D.; et al. 2021 ESC Guidelines on Cardiovascular Disease Prevention in Clinical Practice. Eur. Heart J. 2021, 42, 3227–3337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erlinge, D.; Maehara, A.; Ben-Yehuda, O.; Bøtker, H.E.; Maeng, M.; Kjøller-Hansen, L.; Engstrøm, T.; Matsumura, M.; Crowley, A.; Dressler, O.; et al. Identification of Vulnerable Plaques and Patients by Intracoronary Near-Infrared Spectroscopy and Ultrasound (PROSPECT II): A Prospective Natural History Study. Lancet 2021, 397, 985–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erlinge, D.; Tsimikas, S.; Maeng, M.; Maehara, A.; Larsen, A.I.; Engstrøm, T.; Kjøller-Hansen, L.; Matsumura, M.; Ben-Yehuda, O.; Bøtker, H.E.; et al. Lipoprotein(a), Cholesterol, Triglyceride Levels, and Vulnerable Coronary Plaques: A PROSPECT II Substudy. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2025, 85, 2011–2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shoaran, M.; Maffia, P. Tackling Inflammation in Atherosclerosis. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2024, 21, 442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ridker, P.M.; Bhatt, D.L.; Pradhan, A.D.; Glynn, R.J.; MacFadyen, J.G.; Nissen, S.E.; PROMINENT, REDUCE-IT, and STRENGTH Investigators. Inflammation and Cholesterol as Predictors of Cardiovascular Events among Patients Receiving Statin Therapy: A Collaborative Analysis of Three Randomised Trials. Lancet 2023, 401, 1293–1301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raggi, P.; Genest, J.; Giles, J.T.; Rayner, K.J.; Dwivedi, G.; Beanlands, R.S.; Gupta, M. Role of Inflammation in the Pathogenesis of Atherosclerosis and Therapeutic Interventions. Atherosclerosis 2018, 276, 98–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinarello, C.A.; Simon, A.; van der Meer, J.W.M. Treating Inflammation by Blocking Interleukin-1 in a Broad Spectrum of Diseases. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2012, 11, 633–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Heijden, T.; Kritikou, E.; Venema, W.; van Duijn, J.; van Santbrink, P.J.; Slütter, B.; Foks, A.C.; Bot, I.; Kuiper, J. NLRP3 Inflammasome Inhibition by MCC950 Reduces Atherosclerotic Lesion Development in Apolipoprotein E-Deficient Mice-Brief Report. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2017, 37, 1457–1461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Interleukin-6 Receptor Mendelian Randomisation Analysis (IL6R MR) Consortium; Swerdlow, D.I.; Holmes, M.V.; Kuchenbaecker, K.B.; Engmann, J.E.L.; Shah, T.; Sofat, R.; Guo, Y.; Chung, C.; Peasey, A.; et al. The Interleukin-6 Receptor as a Target for Prevention of Coronary Heart Disease: A Mendelian Randomisation Analysis. Lancet 2012, 379, 1214–1224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imbesi, A.; Greco, A.; Spagnolo, M.; Laudani, C.; Raffo, C.; Finocchiaro, S.; Mazzone, P.M.; Landolina, D.; Mauro, M.S.; Cutore, L.; et al. Targeting Inflammation After Acute Myocardial Infarction. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2025, 86, 1146–1169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Wu, Y.-J.; Qian, J.; Li, J.-J. Landscape of Statin as a Cornerstone in Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Disease. Rev. Cardiovasc. Med. 2023, 24, 373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ridker, P.M.; Mora, S.; Rose, L.; JUPITER Trial Study Group. Percent Reduction in LDL Cholesterol Following High-Intensity Statin Therapy: Potential Implications for Guidelines and for the Prescription of Emerging Lipid-Lowering Agents. Eur. Heart J. 2016, 37, 1373–1379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boekholdt, S.M.; Hovingh, G.K.; Mora, S.; Arsenault, B.J.; Amarenco, P.; Pedersen, T.R.; LaRosa, J.C.; Waters, D.D.; DeMicco, D.A.; Simes, R.J.; et al. Very Low Levels of Atherogenic Lipoproteins and the Risk for Cardiovascular Events: A Meta-Analysis of Statin Trials. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2014, 64, 485–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chasman, D.I.; Giulianini, F.; MacFadyen, J.; Barratt, B.J.; Nyberg, F.; Ridker, P.M. Genetic Determinants of Statin-Induced Low-Density Lipoprotein Cholesterol Reduction: The Justification for the Use of Statins in Prevention: An Intervention Trial Evaluating Rosuvastatin (JUPITER) Trial. Circ. Cardiovasc. Genet. 2012, 5, 257–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reiner, Z. Managing the Residual Cardiovascular Disease Risk Associated with HDL-Cholesterol and Triglycerides in Statin-Treated Patients: A Clinical Update. Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2013, 23, 799–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oesterle, A.; Laufs, U.; Liao, J.K. Pleiotropic Effects of Statins on the Cardiovascular System. Circ. Res. 2017, 120, 229–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mortensen, M.B.; Falk, E.; Li, D.; Nasir, K.; Blaha, M.J.; Sandfort, V.; Rodriguez, C.J.; Ouyang, P.; Budoff, M. Statin Trials, Cardiovascular Events, and Coronary Artery Calcification: Implications for a Trial-Based Approach to Statin Therapy in MESA. JACC Cardiovasc. Imaging 2018, 11, 221–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedersen, T.R. Pleiotropic Effects of Statins: Evidence against Benefits beyond LDL-Cholesterol Lowering. Am. J. Cardiovasc. Drugs 2010, 10 (Suppl. S1), 10–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giacoppo, D.; Gargiulo, G.; Buccheri, S.; Aruta, P.; Byrne, R.A.; Cassese, S.; Dangas, G.; Kastrati, A.; Mehran, R.; Tamburino, C.; et al. Preventive Strategies for Contrast-Induced Acute Kidney Injury in Patients Undergoing Percutaneous Coronary Procedures: Evidence From a Hierarchical Bayesian Network Meta-Analysis of 124 Trials and 28 240 Patients. Circ. Cardiovasc. Interv. 2017, 10, e004383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cholesterol Treatment Trialists’ (CTT) Collaboration; Baigent, C.; Blackwell, L.; Emberson, J.; Holland, L.E.; Reith, C.; Bhala, N.; Peto, R.; Barnes, E.H.; Keech, A.; et al. Efficacy and Safety of More Intensive Lowering of LDL Cholesterol: A Meta-Analysis of Data from 170,000 Participants in 26 Randomised Trials. Lancet 2010, 376, 1670–1681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baigent, C.; Keech, A.; Kearney, P.M.; Blackwell, L.; Buck, G.; Pollicino, C.; Kirby, A.; Sourjina, T.; Peto, R.; Collins, R.; et al. Efficacy and Safety of Cholesterol-Lowering Treatment: Prospective Meta-Analysis of Data from 90,056 Participants in 14 Randomised Trials of Statins. Lancet 2005, 366, 1267–1278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Genser, B.; März, W. Low Density Lipoprotein Cholesterol, Statins and Cardiovascular Events: A Meta-Analysis. Clin. Res. Cardiol. 2006, 95, 393–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Lemos, J.A.; Blazing, M.A.; Wiviott, S.D.; Lewis, E.F.; Fox, K.A.A.; White, H.D.; Rouleau, J.-L.; Pedersen, T.R.; Gardner, L.H.; Mukherjee, R.; et al. Early Intensive vs a Delayed Conservative Simvastatin Strategy in Patients with Acute Coronary Syndromes: Phase Z of the A to Z Trial. JAMA 2004, 292, 1307–1316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarese, E.P.; Kowalewski, M.; Andreotti, F.; van Wely, M.; Camaro, C.; Kolodziejczak, M.; Gorny, B.; Wirianta, J.; Kubica, J.; Kelm, M.; et al. Meta-Analysis of Time-Related Benefits of Statin Therapy in Patients with Acute Coronary Syndrome Undergoing Percutaneous Coronary Intervention. Am. J. Cardiol. 2014, 113, 1753–1764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ray, K.K.; Cannon, C.P.; McCabe, C.H.; Cairns, R.; Tonkin, A.M.; Sacks, F.M.; Jackson, G.; Braunwald, E.; PROVE IT-TIMI 22 Investigators. Early and Late Benefits of High-Dose Atorvastatin in Patients with Acute Coronary Syndromes: Results from the PROVE IT-TIMI 22 Trial. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2005, 46, 1405–1410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, G.G.; Fayyad, R.; Szarek, M.; DeMicco, D.; Olsson, A.G. Early, Intensive Statin Treatment Reduces “hard” Cardiovascular Outcomes after Acute Coronary Syndrome. Eur. J. Prev. Cardiol. 2017, 24, 1294–1296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, G.G.; Olsson, A.G.; Ezekowitz, M.D.; Ganz, P.; Oliver, M.F.; Waters, D.; Zeiher, A.; Chaitman, B.R.; Leslie, S.; Stern, T.; et al. Effects of Atorvastatin on Early Recurrent Ischemic Events in Acute Coronary Syndromes: The MIRACL Study: A Randomized Controlled Trial. JAMA 2001, 285, 1711–1718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berwanger, O.; Santucci, E.V.; de Barros e Silva, P.G.M.; Jesuíno, I.d.A.; Damiani, L.P.; Barbosa, L.M.; Santos, R.H.N.; Laranjeira, L.N.; Egydio, F.d.M.; Borges de Oliveira, J.A.; et al. Effect of Loading Dose of Atorvastatin Prior to Planned Percutaneous Coronary Intervention on Major Adverse Cardiovascular Events in Acute Coronary Syndrome. JAMA 2018, 319, 1331–1340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patti, G.; Cannon, C.P.; Murphy, S.A.; Mega, S.; Pasceri, V.; Briguori, C.; Colombo, A.; Yun, K.H.; Jeong, M.H.; Kim, J.-S.; et al. Clinical Benefit of Statin Pretreatment in Patients Undergoing Percutaneous Coronary Intervention: A Collaborative Patient-Level Meta-Analysis of 13 Randomized Studies. Circulation 2011, 123, 1622–1632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.-S.; Kim, J.; Choi, D.; Lee, C.J.; Lee, S.H.; Ko, Y.-G.; Hong, M.-K.; Kim, B.-K.; Oh, S.J.; Jeon, D.W.; et al. Efficacy of High-Dose Atorvastatin Loading before Primary Percutaneous Coronary Intervention in ST-Segment Elevation Myocardial Infarction: The STATIN STEMI Trial. JACC Cardiovasc. Interv. 2010, 3, 332–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.H.; de Feyter, P.; Serruys, P.W.; Saia, F.; Lemos, P.A.; Goedhart, D.; Soares, P.R.; Umans, V.A.W.M.; Ciccone, M.; Cortellaro, M. Beneficial Effects of Fluvastatin Following Percutaneous Coronary Intervention in Patients with Unstable and Stable Angina: Results from the Lescol Intervention Prevention Study (LIPS). Heart 2004, 90, 1156–1161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, A.S.; Jackson, B.M.; Farrin, A.J.; Efthymiou, M.; Barth, J.H.; Copeland, J.; Bailey, K.M.; Romaine, S.P.R.; Balmforth, A.J.; McCormack, T.; et al. A Randomized, Controlled Trial of Simvastatin versus Rosuvastatin in Patients with Acute Myocardial Infarction: The Secondary Prevention of Acute Coronary Events—Reduction of Cholesterol to Key European Targets Trial. Eur. J. Cardiovasc. Prev. Rehabil. 2009, 16, 712–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cannon, C.P.; Braunwald, E.; McCabe, C.H.; Rader, D.J.; Rouleau, J.L.; Belder, R.; Joyal, S.V.; Hill, K.A.; Pfeffer, M.A.; Skene, A.M.; et al. Intensive versus Moderate Lipid Lowering with Statins after Acute Coronary Syndromes. N. Engl. J. Med. 2004, 350, 1495–1504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedersen, T.R.; Faergeman, O.; Kastelein, J.J.P.; Olsson, A.G.; Tikkanen, M.J.; Holme, I.; Larsen, M.L.; Bendiksen, F.S.; Lindahl, C.; Szarek, M.; et al. High-Dose Atorvastatin vs Usual-Dose Simvastatin for Secondary Prevention after Myocardial Infarction: The IDEAL Study: A Randomized Controlled Trial. JAMA 2005, 294, 2437–2445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phan, B.A.P.; Dayspring, T.D.; Toth, P.P. Ezetimibe Therapy: Mechanism of Action and Clinical Update. Vasc. Health Risk Manag. 2012, 8, 415–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gazi, I.F.; Daskalopoulou, S.S.; Nair, D.R.; Mikhailidis, D.P. Effect of Ezetimibe in Patients Who Cannot Tolerate Statins or Cannot Get to the Low Density Lipoprotein Cholesterol Target despite Taking a Statin. Curr. Med. Res. Opin. 2007, 23, 2183–2192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pandor, A.; Ara, R.M.; Tumur, I.; Wilkinson, A.J.; Paisley, S.; Duenas, A.; Durrington, P.N.; Chilcott, J. Ezetimibe Monotherapy for Cholesterol Lowering in 2722 People: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. J. Intern. Med. 2009, 265, 568–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gagné, C.; Bays, H.E.; Weiss, S.R.; Mata, P.; Quinto, K.; Melino, M.; Cho, M.; Musliner, T.A.; Gumbiner, B.; Ezetimibe Study Group. Efficacy and Safety of Ezetimibe Added to Ongoing Statin Therapy for Treatment of Patients with Primary Hypercholesterolemia. Am. J. Cardiol. 2002, 90, 1084–1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cannon, C.P.; Blazing, M.A.; Giugliano, R.P.; McCagg, A.; White, J.A.; Theroux, P.; Darius, H.; Lewis, B.S.; Ophuis, T.O.; Jukema, J.W.; et al. Ezetimibe Added to Statin Therapy after Acute Coronary Syndromes. N. Engl. J. Med. 2015, 372, 2387–2397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.-J.; Joo, J.H.; Park, S.; Kim, C.; Choi, D.-W.; Hong, S.-J.; Ahn, C.-M.; Kim, J.-S.; Kim, B.-K.; Ko, Y.-G.; et al. Combination Lipid-Lowering Therapy in Patients Undergoing Percutaneous Coronary Intervention. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2023, 82, 401–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, B.-K.; Hong, S.-J.; Lee, Y.-J.; Hong, S.J.; Yun, K.H.; Hong, B.-K.; Heo, J.H.; Rha, S.-W.; Cho, Y.-H.; Lee, S.-J.; et al. Long-Term Efficacy and Safety of Moderate-Intensity Statin with Ezetimibe Combination Therapy versus High-Intensity Statin Monotherapy in Patients with Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Disease (RACING): A Randomised, Open-Label, Non-Inferiority Trial. Lancet 2022, 400, 380–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.-J.; Cha, J.-J.; Choi, W.G.; Lee, W.-S.; Jeong, J.-O.; Choi, S.; Cho, Y.-H.; Park, W.; Yoon, C.-H.; Lee, Y.-J.; et al. Moderate-Intensity Statin With Ezetimibe Combination Therapy vs High-Intensity Statin Monotherapy in Patients at Very High Risk of Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Disease: A Post Hoc Analysis From the RACING Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Cardiol. 2023, 8, 853–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, S.J.; Jeong, H.S.; Ahn, J.C.; Cha, D.-H.; Won, K.H.; Kim, W.; Cho, S.K.; Kim, S.-Y.; Yoo, B.-S.; Sung, K.C.; et al. A Phase III, Multicenter, Randomized, Double-Blind, Active Comparator Clinical Trial to Compare the Efficacy and Safety of Combination Therapy With Ezetimibe and Rosuvastatin Versus Rosuvastatin Monotherapy in Patients With Hypercholesterolemia: I-ROSETTE (Ildong Rosuvastatin & Ezetimibe for Hypercholesterolemia) Randomized Controlled Trial. Clin. Ther. 2018, 40, 226–241.e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calabrò, P.; Spaccarotella, C.; Cesaro, A.; Andò, G.; Piccolo, R.; De Rosa, S.; Zimarino, M.; Mancone, M.; Gragnano, F.; Moscarella, E.; et al. Lipid-Lowering Therapy in Patients with Coronary Artery Disease Undergoing Percutaneous Coronary Interventions in Italy: An Expert Opinion Paper of Interventional Cardiology Working Group of Italian Society of Cardiology. J. Cardiovasc. Med. 2023, 24 (Suppl. S1), e86–e94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, K.-J.; Kim, S.-H.; Yoon, Y.W.; Rha, S.-W.; Hong, S.-J.; Kwak, C.-H.; Kim, W.; Nam, C.-W.; Rhee, M.-Y.; Park, T.-H.; et al. Effect of Fixed-Dose Combinations of Ezetimibe plus Rosuvastatin in Patients with Primary Hypercholesterolemia: MRS-ROZE (Multicenter Randomized Study of ROsuvastatin and eZEtimibe). Cardiovasc. Ther. 2016, 34, 371–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masuda, J.; Tanigawa, T.; Yamada, T.; Nishimura, Y.; Sasou, T.; Nakata, T.; Sawai, T.; Fujimoto, N.; Dohi, K.; Miyahara, M.; et al. Effect of Combination Therapy of Ezetimibe and Rosuvastatin on Regression of Coronary Atherosclerosis in Patients with Coronary Artery Disease. Int. Heart J. 2015, 56, 278–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Zhao, X.; Li, L.; Yao, H.; Jiang, Y.; Zhang, J. Effects of Combination of Ezetimibe and Rosuvastatin on Coronary Artery Plaque in Patients with Coronary Heart Disease. Heart Lung Circ. 2016, 25, 459–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ueki, Y.; Itagaki, T.; Kuwahara, K. Lipid-Lowering Therapy and Coronary Plaque Regression. J. Atheroscler. Thromb. 2024, 31, 1479–1495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballantyne, C.M.; Weiss, R.; Moccetti, T.; Vogt, A.; Eber, B.; Sosef, F.; Duffield, E.; EXPLORER Study Investigators. Efficacy and Safety of Rosuvastatin 40 Mg Alone or in Combination with Ezetimibe in Patients at High Risk of Cardiovascular Disease (Results from the EXPLORER Study). Am. J. Cardiol. 2007, 99, 673–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballantyne, C.M.; Hoogeveen, R.C.; Raya, J.L.; Cain, V.A.; Palmer, M.K.; Karlson, B.W.; GRAVITY Study Investigators. Efficacy, Safety and Effect on Biomarkers Related to Cholesterol and Lipoprotein Metabolism of Rosuvastatin 10 or 20 Mg plus Ezetimibe 10 Mg vs. Simvastatin 40 or 80 Mg plus Ezetimibe 10 Mg in High-Risk Patients: Results of the GRAVITY Randomized Study. Atherosclerosis 2014, 232, 86–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, J.-Y.; Kim, S.; Cho, J.; Chun, S.-Y.; You, S.C.; Kim, J.-S. Comparative Effectiveness of Moderate-Intensity Statin with Ezetimibe Therapy versus High-Intensity Statin Monotherapy in Patients with Acute Coronary Syndrome: A Nationwide Cohort Study. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallego-Colon, E.; Daum, A.; Yosefy, C. Statins and PCSK9 Inhibitors: A New Lipid-Lowering Therapy. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2020, 878, 173114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agnello, F.; Mauro, M.S.; Rochira, C.; Landolina, D.; Finocchiaro, S.; Greco, A.; Ammirabile, N.; Raffo, C.; Mazzone, P.M.; Spagnolo, M.; et al. PCSK9 Inhibitors: Current Status and Emerging Frontiers in Lipid Control. Expert Rev. Cardiovasc. Ther. 2024, 22, 41–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gragnano, F.; Natale, F.; Concilio, C.; Fimiani, F.; Cesaro, A.; Sperlongano, S.; Crisci, M.; Limongelli, G.; Calabrò, R.; Russo, M.; et al. Adherence to Proprotein Convertase Subtilisin/Kexin 9 Inhibitors in High Cardiovascular Risk Patients: An Italian Single-Center Experience. J. Cardiovasc. Med. 2018, 19, 75–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cesaro, A.; Gragnano, F.; Fimiani, F.; Moscarella, E.; Diana, V.; Pariggiano, I.; Concilio, C.; Natale, F.; Limongelli, G.; Bossone, E.; et al. Impact of PCSK9 Inhibitors on the Quality of Life of Patients at High Cardiovascular Risk. Eur. J. Prev. Cardiol. 2020, 27, 556–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiang, C.-E.; Schwartz, G.G.; Elbez, Y.; Szarek, M.; Bhatt, D.L.; Bittner, V.A.; Diaz, R.; Erglis, A.; Goodman, S.G.; Hagström, E.; et al. Alirocumab and Cardiovascular Outcomes in Patients With Previous Myocardial Infarction: Prespecified Subanalysis From ODYSSEY OUTCOMES. Can. J. Cardiol. 2022, 38, 1542–1549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mehta, S.R.; Pare, G.; Lonn, E.M.; Jolly, S.S.; Natarajan, M.K.; Pinilla-Echeverri, N.; Schwalm, J.-D.; Sheth, T.N.; Sibbald, M.; Tsang, M.; et al. Effects of Routine Early Treatment with PCSK9 Inhibitors in Patients Undergoing Primary Percutaneous Coronary Intervention for ST-Segment Elevation Myocardial Infarction: A Randomised, Double-Blind, Sham-Controlled Trial. EuroIntervention 2022, 18, e888–e896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Räber, L.; Ueki, Y.; Otsuka, T.; Losdat, S.; Häner, J.D.; Lonborg, J.; Fahrni, G.; Iglesias, J.F.; van Geuns, R.-J.; Ondracek, A.S.; et al. Effect of Alirocumab Added to High-Intensity Statin Therapy on Coronary Atherosclerosis in Patients With Acute Myocardial Infarction: The PACMAN-AMI Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA 2022, 327, 1771–1781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nissen, S.E.; Stroes, E.; Dent-Acosta, R.E.; Rosenson, R.S.; Lehman, S.J.; Sattar, N.; Preiss, D.; Bruckert, E.; Ceška, R.; Lepor, N.; et al. Efficacy and Tolerability of Evolocumab vs Ezetimibe in Patients With Muscle-Related Statin Intolerance: The GAUSS-3 Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA 2016, 315, 1580–1590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giugliano, R.P.; Pedersen, T.R.; Park, J.-G.; De Ferrari, G.M.; Gaciong, Z.A.; Ceska, R.; Toth, K.; Gouni-Berthold, I.; Lopez-Miranda, J.; Schiele, F.; et al. Clinical Efficacy and Safety of Achieving Very Low LDL-Cholesterol Concentrations with the PCSK9 Inhibitor Evolocumab: A Prespecified Secondary Analysis of the FOURIER Trial. Lancet 2017, 390, 1962–1971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabatine, M.S.; De Ferrari, G.M.; Giugliano, R.P.; Huber, K.; Lewis, B.S.; Ferreira, J.; Kuder, J.F.; Murphy, S.A.; Wiviott, S.D.; Kurtz, C.E.; et al. Clinical Benefit of Evolocumab by Severity and Extent of Coronary Artery Disease: Analysis From FOURIER. Circulation 2018, 138, 756–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koskinas, K.C.; Windecker, S.; Pedrazzini, G.; Mueller, C.; Cook, S.; Matter, C.M.; Muller, O.; Häner, J.; Gencer, B.; Crljenica, C.; et al. Evolocumab for Early Reduction of LDL Cholesterol Levels in Patients With Acute Coronary Syndromes (EVOPACS). J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2019, 74, 2452–2462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leucker, T.M.; Blaha, M.J.; Jones, S.R.; Vavuranakis, M.A.; Williams, M.S.; Lai, H.; Schindler, T.H.; Latina, J.; Schulman, S.P.; Gerstenblith, G. Effect of Evolocumab on Atherogenic Lipoproteins During the Peri- and Early Postinfarction Period: A Placebo-Controlled, Randomized Trial. Circulation 2020, 142, 419–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nicholls, S.J.; Kataoka, Y.; Nissen, S.E.; Prati, F.; Windecker, S.; Puri, R.; Hucko, T.; Aradi, D.; Herrman, J.-P.R.; Hermanides, R.S.; et al. Effect of Evolocumab on Coronary Plaque Phenotype and Burden in Statin-Treated Patients Following Myocardial Infarction. JACC Cardiovasc. Imaging 2022, 15, 1308–1321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Donoghue, M.L.; Giugliano, R.P.; Wiviott, S.D.; Atar, D.; Keech, A.; Kuder, J.F.; Im, K.; Murphy, S.A.; Flores-Arredondo, J.H.; López, J.A.G.; et al. Long-Term Evolocumab in Patients with Established Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Disease. Circulation 2022, 146, 1109–1119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Said, S.; O’Donoghue, M.L.; Ran, X.; Murphy, S.A.; Atar, D.; Keech, A.; Flores-Arredondo, J.H.; Wang, B.; Sabatine, M.S.; Giugliano, R.P. Long-Term Lipid Lowering With Evolocumab in Older Individuals. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2025, 85, 504–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ballantyne, C.M.; Gellis, L.; Tardif, J.-C.; Banka, P.; Navar, A.M.; Asprusten, E.A.; Scott, R.; Stroes, E.S.G.; Froman, S.; Mendizabal, G.; et al. Efficacy and Safety of Oral PCSK9 Inhibitor Enlicitide in Adults With Heterozygous Familial Hypercholesterolemia: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA 2025, e2520620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoekenbroek, R.M.; Kallend, D.; Wijngaard, P.L.; Kastelein, J.J. Inclisiran for the Treatment of Cardiovascular Disease: The ORION Clinical Development Program. Future Cardiol. 2018, 14, 433–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ray, K.K.; Wright, R.S.; Kallend, D.; Koenig, W.; Leiter, L.A.; Raal, F.J.; Bisch, J.A.; Richardson, T.; Jaros, M.; Wijngaard, P.L.J.; et al. Two Phase 3 Trials of Inclisiran in Patients with Elevated LDL Cholesterol. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 382, 1507–1519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ray, K.K.; Troquay, R.P.T.; Visseren, F.L.J.; Leiter, L.A.; Scott Wright, R.; Vikarunnessa, S.; Talloczy, Z.; Zang, X.; Maheux, P.; Lesogor, A.; et al. Long-Term Efficacy and Safety of Inclisiran in Patients with High Cardiovascular Risk and Elevated LDL Cholesterol (ORION-3): Results from the 4-Year Open-Label Extension of the ORION-1 Trial. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2023, 11, 109–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wright, R.S.; Raal, F.J.; Koenig, W.; Landmesser, U.; Leiter, L.A.; Vikarunnessa, S.; Lesogor, A.; Maheux, P.; Talloczy, Z.; Zang, X.; et al. Inclisiran Administration Potently and Durably Lowers LDL-C over an Extended-Term Follow-up: The ORION-8 Trial. Cardiovasc. Res. 2024, 120, 1400–1410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wiegman, A.; Peterson, A.L.; Hegele, R.A.; Bruckert, E.; Schweizer, A.; Lesogor, A.; Wang, Y.; Defesche, J. Efficacy and Safety of Inclisiran in Adolescents With Genetically Confirmed Homozygous Familial Hypercholesterolemia: Results From the Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Part of the ORION-13 Randomized Trial. Circulation 2025, 151, 1758–1766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gencer, B.; Mach, F.; Murphy, S.A.; De Ferrari, G.M.; Huber, K.; Lewis, B.S.; Ferreira, J.; Kurtz, C.E.; Wang, H.; Honarpour, N.; et al. Efficacy of Evolocumab on Cardiovascular Outcomes in Patients With Recent Myocardial Infarction: A Prespecified Secondary Analysis From the FOURIER Trial. JAMA Cardiol. 2020, 5, 952–957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masiero, G.; Franzone, A.; Silvestri, T.; Castiglioni, B.; Greco, F.; La Manna, A.G.; Limbruno, U.; Longoni, M.; Marchese, A.; Mattesini, A.; et al. PCSK9 inhibitor use in high cardiovascular risk patients: An interventionalist’s overview on efficacy, current recommendations and factual prescription. G. Ital. Cardiol. 2020, 21, 264–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gargiulo, P.; Basile, C.; Galasso, G.; Bellino, M.; D’Elia, D.; Patti, G.; Bosco, M.; Prinetti, M.; Andò, G.; Campanella, F.; et al. Strike Early-Strike Strong Lipid-Lowering Strategy with Proprotein Convertase Subtilisin/Kexin Type 9 Inhibitors in Acute Coronary Syndrome Patients: Real-World Evidence from the AT-TARGET-IT Registry. Eur. J. Prev. Cardiol. 2024, 31, 1806–1816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canonico, M.E.; Hess, C.N.; Cannon, C.P. In-Hospital Use of PCSK9 Inhibitors in the Post ACS Patient: What Does the Evidence Show? Curr. Atheroscler. Rep. 2023, 25, 381–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grundy, S.M.; Stone, N.J.; Bailey, A.L.; Beam, C.; Birtcher, K.K.; Blumenthal, R.S.; Braun, L.T.; de Ferranti, S.; Faiella-Tommasino, J.; Forman, D.E.; et al. 2018 AHA/ACC/AACVPR/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/ADA/AGS/APhA/ASPC/NLA/PCNA Guideline on the Management of Blood Cholesterol: Executive Summary: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2019, 73, 3168–3209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ray, K.K.; Landmesser, U.; Leiter, L.A.; Kallend, D.; Dufour, R.; Karakas, M.; Hall, T.; Troquay, R.P.T.; Turner, T.; Visseren, F.L.J.; et al. Inclisiran in Patients at High Cardiovascular Risk with Elevated LDL Cholesterol. N. Engl. J. Med. 2017, 376, 1430–1440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ray, K.K.; Stoekenbroek, R.M.; Kallend, D.; Leiter, L.A.; Landmesser, U.; Wright, R.S.; Wijngaard, P.; Kastelein, J.J.P. Effect of an siRNA Therapeutic Targeting PCSK9 on Atherogenic Lipoproteins: Prespecified Secondary End Points in ORION 1. Circulation 2018, 138, 1304–1316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamashita, S.; Kiyosue, A.; Maheux, P.; Mena-Madrazo, J.; Lesogor, A.; Shao, Q.; Tamaki, Y.; Nakamura, H.; Akahori, M.; Kajinami, K. Efficacy, Safety, and Pharmacokinetics of Inclisiran in Japanese Patients: Results from ORION-15. J. Atheroscler. Thromb. 2024, 31, 876–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, R.S.; Koenig, W.; Landmesser, U.; Leiter, L.A.; Raal, F.J.; Schwartz, G.G.; Lesogor, A.; Maheux, P.; Stratz, C.; Zang, X.; et al. Safety and Tolerability of Inclisiran for Treatment of Hypercholesterolemia in 7 Clinical Trials. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2023, 82, 2251–2261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hovingh, G.K.; Lepor, N.E.; Kallend, D.; Stoekenbroek, R.M.; Wijngaard, P.L.J.; Raal, F.J. Inclisiran Durably Lowers Low-Density Lipoprotein Cholesterol and Proprotein Convertase Subtilisin/Kexin Type 9 Expression in Homozygous Familial Hypercholesterolemia: The ORION-2 Pilot Study. Circulation 2020, 141, 1829–1831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raal, F.; Durst, R.; Bi, R.; Talloczy, Z.; Maheux, P.; Lesogor, A.; Kastelein, J.J.P. ORION-5 Study Investigators Efficacy, Safety, and Tolerability of Inclisiran in Patients With Homozygous Familial Hypercholesterolemia: Results From the ORION-5 Randomized Clinical Trial. Circulation 2024, 149, 354–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raal, F.J.; Kallend, D.; Ray, K.K.; Turner, T.; Koenig, W.; Wright, R.S.; Wijngaard, P.L.J.; Curcio, D.; Jaros, M.J.; Leiter, L.A.; et al. Inclisiran for the Treatment of Heterozygous Familial Hypercholesterolemia. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 382, 1520–1530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ballantyne, C.M.; Laufs, U.; Ray, K.K.; Leiter, L.A.; Bays, H.E.; Goldberg, A.C.; Stroes, E.S.; MacDougall, D.; Zhao, X.; Catapano, A.L. Bempedoic Acid plus Ezetimibe Fixed-Dose Combination in Patients with Hypercholesterolemia and High CVD Risk Treated with Maximally Tolerated Statin Therapy. Eur. J. Prev. Cardiol. 2020, 27, 593–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ray, K.K.; Bays, H.E.; Catapano, A.L.; Lalwani, N.D.; Bloedon, L.T.; Sterling, L.R.; Robinson, P.L.; Ballantyne, C.M.; CLEAR Harmony Trial. Safety and Efficacy of Bempedoic Acid to Reduce LDL Cholesterol. N. Engl. J. Med. 2019, 380, 1022–1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nissen, S.E.; Lincoff, A.M.; Brennan, D.; Ray, K.K.; Mason, D.; Kastelein, J.J.P.; Thompson, P.D.; Libby, P.; Cho, L.; Plutzky, J.; et al. Bempedoic Acid and Cardiovascular Outcomes in Statin-Intolerant Patients. N. Engl. J. Med. 2023, 388, 1353–1364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goldberg, A.C.; Leiter, L.A.; Stroes, E.S.G.; Baum, S.J.; Hanselman, J.C.; Bloedon, L.T.; Lalwani, N.D.; Patel, P.M.; Zhao, X.; Duell, P.B. Effect of Bempedoic Acid vs Placebo Added to Maximally Tolerated Statins on Low-Density Lipoprotein Cholesterol in Patients at High Risk for Cardiovascular Disease: The CLEAR Wisdom Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA 2019, 322, 1780–1788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raposeiras-Roubín, S.; Abu-Assi, E.; Pérez Rivera, J.Á.; Jorge Pérez, P.; Ayesta López, A.; Viana Tejedor, A.; Corbí Pascual, M.J.; Carrasquer, A.; Jiménez Méndez, C.; González Cambeiro, C.; et al. Efficacy and Safety of Bempedoic Acid in Acute Coronary Syndrome. Design of the Clinical Trial ES-BempeDACS. Rev. Espanola Cardiol. Engl. Ed. 2025, 78, 56–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicholls, S.J.; Nelson, A.J.; Ditmarsch, M.; Kastelein, J.J.P.; Ballantyne, C.M.; Ray, K.K.; Navar, A.M.; Nissen, S.E.; Harada-Shiba, M.; Curcio, D.L.; et al. Safety and Efficacy of Obicetrapib in Patients at High Cardiovascular Risk. N. Engl. J. Med. 2025, 393, 51–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarraju, A.; Brennan, D.; Hayden, K.; Stronczek, A.; Goldberg, A.C.; Michos, E.D.; McGuire, D.K.; Mason, D.; Tercek, G.; Nicholls, S.J.; et al. Fixed-dose combination of obicetrapib and ezetimibe for LDL cholesterol reduction (TANDEM): A phase 3, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2025, 405, 1757–1768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicholls, S.J.; Ditmarsch, M.; Kastelein, J.J.; Rigby, S.P.; Kling, D.; Curcio, D.L.; Alp, N.J.; Davidson, M.H. Lipid Lowering Effects of the CETP Inhibitor Obicetrapib in Combination with High-Intensity Statins: A Randomized Phase 2 Trial. Nat. Med. 2022, 28, 1672–1678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicholls, S.J.; Nelson, A.J.; Ditmarsch, M.; Kastelein, J.J.P.; Ballantyne, C.M.; Ray, K.K.; Navar, A.M.; Nissen, S.E.; Goldberg, A.C.; Brunham, L.R.; et al. Obicetrapib on Top of Maximally Tolerated Lipid-Modifying Therapies in Participants with or at High Risk for Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Disease: Rationale and Designs of BROADWAY and BROOKLYN. Am. Heart J. 2024, 274, 32–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, G.; Mason, R.P.; Steg, P.G.; Bhatt, D.L. Omega-3 Fatty Acids for Cardiovascular Event Lowering. Eur. J. Prev. Cardiol. 2024, 31, 1005–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yokoyama, M.; Origasa, H.; Matsuzaki, M.; Matsuzawa, Y.; Saito, Y.; Ishikawa, Y.; Oikawa, S.; Sasaki, J.; Hishida, H.; Itakura, H.; et al. Effects of Eicosapentaenoic Acid on Major Coronary Events in Hypercholesterolaemic Patients (JELIS): A Randomised Open-Label, Blinded Endpoint Analysis. Lancet 2007, 369, 1090–1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nosaka, K.; Miyoshi, T.; Iwamoto, M.; Kajiya, M.; Okawa, K.; Tsukuda, S.; Yokohama, F.; Sogo, M.; Nishibe, T.; Matsuo, N.; et al. Early Initiation of Eicosapentaenoic Acid and Statin Treatment Is Associated with Better Clinical Outcomes than Statin Alone in Patients with Acute Coronary Syndromes: 1-Year Outcomes of a Randomized Controlled Study. Int. J. Cardiol. 2017, 228, 173–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicholls, S.J.; Lincoff, A.M.; Garcia, M.; Bash, D.; Ballantyne, C.M.; Barter, P.J.; Davidson, M.H.; Kastelein, J.J.P.; Koenig, W.; McGuire, D.K.; et al. Effect of High-Dose Omega-3 Fatty Acids vs. Corn Oil on Major Adverse Cardiovascular Events in Patients at High Cardiovascular Risk: The STRENGTH Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA 2020, 324, 2268–2280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyauchi, K.; Iwata, H.; Nishizaki, Y.; Inoue, T.; Hirayama, A.; Kimura, K.; Ozaki, Y.; Murohara, T.; Ueshima, K.; Kuwabara, Y.; et al. Randomized Trial for Evaluation in Secondary Prevention Efficacy of Combination Therapy-Statin and Eicosapentaenoic Acid (RESPECT-EPA). Circulation 2024, 150, 425–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Risk and Prevention Study Collaborative Group; Roncaglioni, M.C.; Tombesi, M.; Avanzini, F.; Barlera, S.; Caimi, V.; Longoni, P.; Marzona, I.; Milani, V.; Silletta, M.G.; et al. N-3 Fatty Acids in Patients with Multiple Cardiovascular Risk Factors. N. Engl. J. Med. 2013, 368, 1800–1808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalstad, A.A.; Myhre, P.L.; Laake, K.; Tveit, S.H.; Schmidt, E.B.; Smith, P.; Nilsen, D.W.T.; Tveit, A.; Fagerland, M.W.; Solheim, S.; et al. Effects of n-3 Fatty Acid Supplements in Elderly Patients After Myocardial Infarction: A Randomized, Controlled Trial. Circulation 2021, 143, 528–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatt, D.L.; Steg, P.G.; Miller, M.; Brinton, E.A.; Jacobson, T.A.; Ketchum, S.B.; Doyle, R.T.; Juliano, R.A.; Jiao, L.; Granowitz, C.; et al. Cardiovascular Risk Reduction with Icosapent Ethyl for Hypertriglyceridemia. N. Engl. J. Med. 2019, 380, 11–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballantyne, C.M.; Bays, H.E.; Kastelein, J.J.; Stein, E.; Isaacsohn, J.L.; Braeckman, R.A.; Soni, P.N. Efficacy and Safety of Eicosapentaenoic Acid Ethyl Ester (AMR101) Therapy in Statin-Treated Patients with Persistent High Triglycerides (from the ANCHOR Study). Am. J. Cardiol. 2012, 110, 984–992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bays, H.E.; Ballantyne, C.M.; Kastelein, J.J.; Isaacsohn, J.L.; Braeckman, R.A.; Soni, P.N. Eicosapentaenoic Acid Ethyl Ester (AMR101) Therapy in Patients with Very High Triglyceride Levels (from the Multi-Center, plAcebo-Controlled, Randomized, Double-blINd, 12-Week Study with an Open-Label Extension [MARINE] Trial). Am. J. Cardiol. 2011, 108, 682–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kastelein, J.J.P.; Maki, K.C.; Susekov, A.; Ezhov, M.; Nordestgaard, B.G.; Machielse, B.N.; Kling, D.; Davidson, M.H. Omega-3 Free Fatty Acids for the Treatment of Severe Hypertriglyceridemia: The EpanoVa fOr Lowering Very High triglyceridEs (EVOLVE) Trial. J. Clin. Lipidol. 2014, 8, 94–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stroes, E.S.G.; Susekov, A.V.; de Bruin, T.W.A.; Kvarnström, M.; Yang, H.; Davidson, M.H. Omega-3 Carboxylic Acids in Patients with Severe Hypertriglyceridemia: EVOLVE II, a Randomized, Placebo-Controlled Trial. J. Clin. Lipidol. 2018, 12, 321–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rauch, B.; Schiele, R.; Schneider, S.; Diller, F.; Victor, N.; Gohlke, H.; Gottwik, M.; Steinbeck, G.; Del Castillo, U.; Sack, R.; et al. OMEGA, a Randomized, Placebo-Controlled Trial to Test the Effect of Highly Purified Omega-3 Fatty Acids on Top of Modern Guideline-Adjusted Therapy after Myocardial Infarction. Circulation 2010, 122, 2152–2159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwak, S.M.; Myung, S.-K.; Lee, Y.J.; Seo, H.G.; Korean Meta-analysis Study Group. Efficacy of Omega-3 Fatty Acid Supplements (Eicosapentaenoic Acid and Docosahexaenoic Acid) in the Secondary Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease: A Meta-Analysis of Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Trials. Arch. Intern. Med. 2012, 172, 686–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, S.U.; Lone, A.N.; Khan, M.S.; Virani, S.S.; Blumenthal, R.S.; Nasir, K.; Miller, M.; Michos, E.D.; Ballantyne, C.M.; Boden, W.E.; et al. Effect of Omega-3 Fatty Acids on Cardiovascular Outcomes: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. EClinicalMedicine 2021, 38, 100997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doshi, R.; Kumar, A.; Thakkar, S.; Shariff, M.; Adalja, D.; Doshi, A.; Taha, M.; Gupta, R.; Desai, R.; Shah, J.; et al. Meta-Analysis Comparing Combined Use of Eicosapentaenoic Acid and Statin to Statin Alone. Am. J. Cardiol. 2020, 125, 198–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, J.; Liu, M.; Yang, D.; Zhang, Y.; An, F. Efficacy and Safety of Omega-3 Fatty Acids in the Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Cardiovasc. Drugs Ther. 2024, 38, 799–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gaudet, D.; Kereiakes, D.J.; McKenney, J.M.; Roth, E.M.; Hanotin, C.; Gipe, D.; Du, Y.; Ferrand, A.-C.; Ginsberg, H.N.; Stein, E.A. Effect of Alirocumab, a Monoclonal Proprotein Convertase Subtilisin/Kexin 9 Antibody, on Lipoprotein(a) Concentrations (a Pooled Analysis of 150 Mg Every Two Weeks Dosing from Phase 2 Trials). Am. J. Cardiol. 2014, 114, 711–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raal, F.J.; Giugliano, R.P.; Sabatine, M.S.; Koren, M.J.; Langslet, G.; Bays, H.; Blom, D.; Eriksson, M.; Dent, R.; Wasserman, S.M.; et al. Reduction in Lipoprotein(a) with PCSK9 Monoclonal Antibody Evolocumab (AMG 145): A Pooled Analysis of More than 1300 Patients in 4 Phase II Trials. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2014, 63, 1278–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raal, F.J.; Giugliano, R.P.; Sabatine, M.S.; Koren, M.J.; Blom, D.; Seidah, N.G.; Honarpour, N.; Lira, A.; Xue, A.; Chiruvolu, P.; et al. PCSK9 Inhibition-Mediated Reduction in Lp(a) with Evolocumab: An Analysis of 10 Clinical Trials and the LDL Receptor’s Role. J. Lipid Res. 2016, 57, 1086–1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Donoghue, M.L.; Rosenson, R.S.; Gencer, B.; López, J.A.G.; Lepor, N.E.; Baum, S.J.; Stout, E.; Gaudet, D.; Knusel, B.; Kuder, J.F.; et al. Small Interfering RNA to Reduce Lipoprotein(a) in Cardiovascular Disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 2022, 387, 1855–1864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeang, C.; Karwatowska-Prokopczuk, E.; Su, F.; Dinh, B.; Xia, S.; Witztum, J.L.; Tsimikas, S. Effect of Pelacarsen on Lipoprotein(a) Cholesterol and Corrected Low-Density Lipoprotein Cholesterol. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2022, 79, 1035–1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsimikas, S.; Karwatowska-Prokopczuk, E.; Gouni-Berthold, I.; Tardif, J.-C.; Baum, S.J.; Steinhagen-Thiessen, E.; Shapiro, M.D.; Stroes, E.S.; Moriarty, P.M.; Nordestgaard, B.G.; et al. Lipoprotein(a) Reduction in Persons with Cardiovascular Disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 382, 244–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Viney, N.J.; van Capelleveen, J.C.; Geary, R.S.; Xia, S.; Tami, J.A.; Yu, R.Z.; Marcovina, S.M.; Hughes, S.G.; Graham, M.J.; Crooke, R.M.; et al. Antisense Oligonucleotides Targeting Apolipoprotein(a) in People with Raised Lipoprotein(a): Two Randomised, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled, Dose-Ranging Trials. Lancet 2016, 388, 2239–2253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Donoghue, M.L.; G López, J.A.; Knusel, B.; Gencer, B.; Wang, H.; Wu, Y.; Kassahun, H.; Sabatine, M.S. Study Design and Rationale for the Olpasiran Trials of Cardiovascular Events And lipoproteiN(a) Reduction-DOSE Finding Study (OCEAN(a)-DOSE). Am. Heart J. 2022, 251, 61–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nicholls, S.J.; Ni, W.; Rhodes, G.M.; Nissen, S.E.; Navar, A.M.; Michael, L.F.; Haupt, A.; Krege, J.H. Oral Muvalaplin for Lowering of Lipoprotein(a): A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA 2025, 333, 222–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nissen, S.E.; Linnebjerg, H.; Shen, X.; Wolski, K.; Ma, X.; Lim, S.; Michael, L.F.; Ruotolo, G.; Gribble, G.; Navar, A.M.; et al. Lepodisiran, an Extended-Duration Short Interfering RNA Targeting Lipoprotein(a): A Randomized Dose-Ascending Clinical Trial. JAMA 2023, 330, 2075–2083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nissen, S.E.; Wolski, K.; Watts, G.F.; Koren, M.J.; Fok, H.; Nicholls, S.J.; Rider, D.A.; Cho, L.; Romano, S.; Melgaard, C.; et al. Single Ascending and Multiple-Dose Trial of Zerlasiran, a Short Interfering RNA Targeting Lipoprotein(a): A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA 2024, 331, 1534–1543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leung, Y.Y.; Yao Hui, L.L.; Kraus, V.B. Colchicine—Update on Mechanisms of Action and Therapeutic Uses. Semin. Arthritis Rheum. 2015, 45, 341–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michalkova, R.; Mirossay, L.; Gazdova, M.; Kello, M.; Mojzis, J. Molecular Mechanisms of Antiproliferative Effects of Natural Chalcones. Cancers 2021, 13, 2730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adler, Y.; Charron, P.; Imazio, M.; Badano, L.; Barón-Esquivias, G.; Bogaert, J.; Brucato, A.; Gueret, P.; Klingel, K.; Lionis, C.; et al. 2015 ESC Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Management of Pericardial Diseases: The Task Force for the Diagnosis and Management of Pericardial Diseases of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC)Endorsed by: The European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS). Eur. Heart J. 2015, 36, 2921–2964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imazio, M.; Brucato, A.; Cemin, R.; Ferrua, S.; Maggiolini, S.; Beqaraj, F.; Demarie, D.; Forno, D.; Ferro, S.; Maestroni, S.; et al. A Randomized Trial of Colchicine for Acute Pericarditis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2013, 369, 1522–1528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imazio, M.; Belli, R.; Brucato, A.; Cemin, R.; Ferrua, S.; Beqaraj, F.; Demarie, D.; Ferro, S.; Forno, D.; Maestroni, S.; et al. Efficacy and Safety of Colchicine for Treatment of Multiple Recurrences of Pericarditis (CORP-2): A Multicentre, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled, Randomised Trial. Lancet 2014, 383, 2232–2237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deftereos, S.; Giannopoulos, G.; Angelidis, C.; Alexopoulos, N.; Filippatos, G.; Papoutsidakis, N.; Sianos, G.; Goudevenos, J.; Alexopoulos, D.; Pyrgakis, V.; et al. Anti-Inflammatory Treatment With Colchicine in Acute Myocardial Infarction: A Pilot Study. Circulation 2015, 132, 1395–1403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akodad, M.; Lattuca, B.; Nagot, N.; Georgescu, V.; Buisson, M.; Cristol, J.-P.; Leclercq, F.; Macia, J.-C.; Gervasoni, R.; Cung, T.-T.; et al. COLIN Trial: Value of Colchicine in the Treatment of Patients with Acute Myocardial Infarction and Inflammatory Response. Arch. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2017, 110, 395–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hennessy, T.; Soh, L.; Bowman, M.; Kurup, R.; Schultz, C.; Patel, S.; Hillis, G.S. The Low Dose Colchicine after Myocardial Infarction (LoDoCo-MI) Study: A Pilot Randomized Placebo Controlled Trial of Colchicine Following Acute Myocardial Infarction. Am. Heart J. 2019, 215, 62–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tong, D.C.; Quinn, S.; Nasis, A.; Hiew, C.; Roberts-Thomson, P.; Adams, H.; Sriamareswaran, R.; Htun, N.M.; Wilson, W.; Stub, D.; et al. Colchicine in Patients With Acute Coronary Syndrome: The Australian COPS Randomized Clinical Trial. Circulation 2020, 142, 1890–1900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mewton, N.; Roubille, F.; Bresson, D.; Prieur, C.; Bouleti, C.; Bochaton, T.; Ivanes, F.; Dubreuil, O.; Biere, L.; Hayek, A.; et al. Effect of Colchicine on Myocardial Injury in Acute Myocardial Infarction. Circulation 2021, 144, 859–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tardif, J.-C.; Kouz, S.; Waters, D.D.; Bertrand, O.F.; Diaz, R.; Maggioni, A.P.; Pinto, F.J.; Ibrahim, R.; Gamra, H.; Kiwan, G.S.; et al. Efficacy and Safety of Low-Dose Colchicine after Myocardial Infarction. N. Engl. J. Med. 2019, 381, 2497–2505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vaidya, K.; Arnott, C.; Martínez, G.J.; Ng, B.; McCormack, S.; Sullivan, D.R.; Celermajer, D.S.; Patel, S. Colchicine Therapy and Plaque Stabilization in Patients With Acute Coronary Syndrome: A CT Coronary Angiography Study. JACC Cardiovasc. Imaging 2018, 11, 305–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shah, B.; Pillinger, M.; Zhong, H.; Cronstein, B.; Xia, Y.; Lorin, J.D.; Smilowitz, N.R.; Feit, F.; Ratnapala, N.; Keller, N.M.; et al. Effects of Acute Colchicine Administration Prior to Percutaneous Coronary Intervention: COLCHICINE-PCI Randomized Trial. Circ. Cardiovasc. Interv. 2020, 13, e008717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, M.; Yang, Y.; Dong, S.-L.; Zhao, C.; Yang, F.; Yuan, Y.-F.; Liao, Y.-H.; He, S.-L.; Liu, K.; Wei, F.; et al. Effect of Colchicine on Coronary Plaque Stability in Acute Coronary Syndrome as Assessed by Optical Coherence Tomography: The COLOCT Randomized Clinical Trial. Circulation 2024, 150, 981–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jolly, S.S.; d’Entremont, M.-A.; Lee, S.F.; Mian, R.; Tyrwhitt, J.; Kedev, S.; Montalescot, G.; Cornel, J.H.; Stanković, G.; Moreno, R.; et al. Colchicine in Acute Myocardial Infarction. N. Engl. J. Med. 2025, 392, 633–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nidorf, S.M.; Eikelboom, J.W.; Budgeon, C.A.; Thompson, P.L. Low-Dose Colchicine for Secondary Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2013, 61, 404–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nidorf, S.M.; Fiolet, A.T.L.; Mosterd, A.; Eikelboom, J.W.; Schut, A.; Opstal, T.S.J.; The, S.H.K.; Xu, X.-F.; Ireland, M.A.; Lenderink, T.; et al. Colchicine in Patients with Chronic Coronary Disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 383, 1838–1847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- d’Entremont, M.-A.; Poorthuis, M.H.F.; Fiolet, A.T.L.; Amarenco, P.; Boczar, K.E.; Buysschaert, I.; Chan, N.C.; Cornel, J.H.; Jannink, J.; Jansen, S.; et al. Colchicine for Secondary Prevention of Vascular Events: A Meta-Analysis of Trials. Eur. Heart J. 2025, 46, 2564–2575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bedoui, Y.; Guillot, X.; Sélambarom, J.; Guiraud, P.; Giry, C.; Jaffar-Bandjee, M.C.; Ralandison, S.; Gasque, P. Methotrexate an Old Drug with New Tricks. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 5023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanoodi, M.; Mittal, M. Methotrexate. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Westlake, S.L.; Colebatch, A.N.; Baird, J.; Kiely, P.; Quinn, M.; Choy, E.; Ostor, A.J.K.; Edwards, C.J. The Effect of Methotrexate on Cardiovascular Disease in Patients with Rheumatoid Arthritis: A Systematic Literature Review. Rheumatology 2010, 49, 295–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Micha, R.; Imamura, F.; Wyler von Ballmoos, M.; Solomon, D.H.; Hernán, M.A.; Ridker, P.M.; Mozaffarian, D. Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Methotrexate Use and Risk of Cardiovascular Disease. Am. J. Cardiol. 2011, 108, 1362–1370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferrari, A.G.; Maranhão, R.C.; Salsoso, R.; Baldo, V.M.G.T.F.; Furtado, R.H.M.; Dalçóquio, T.F.; Nakashima, C.A.K.; Baracioli, L.M.; Lima, F.G.; Morikawa, A.T.; et al. Effect of Intravenous Methotrexate Carried by Lipid Nanoemulsion in Patients with Anterior ST-Elevation Myocardial Infarction. Int. J. Cardiol. Heart Vasc. 2025, 60, 101771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ridker, P.M.; Everett, B.M.; Pradhan, A.; MacFadyen, J.G.; Solomon, D.H.; Zaharris, E.; Mam, V.; Hasan, A.; Rosenberg, Y.; Iturriaga, E.; et al. Low-Dose Methotrexate for the Prevention of Atherosclerotic Events. N. Engl. J. Med. 2019, 380, 752–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreira, D.M.; Lueneberg, M.E.; da Silva, R.L.; Fattah, T.; Gottschall, C.A.M. MethotrexaTE THerapy in ST-Segment Elevation MYocardial InfarctionS: A Randomized Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Trial (TETHYS Trial). J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacol. Ther. 2017, 22, 538–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, E.S.L.; Cronstein, B.N. Methotrexate—How Does It Really Work? Nat. Rev. Rheumatol. 2010, 6, 175–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ridker, P.M.; Howard, C.P.; Walter, V.; Everett, B.; Libby, P.; Hensen, J.; Thuren, T.; CANTOS Pilot Investigative Group. Effects of Interleukin-1β Inhibition with Canakinumab on Hemoglobin A1c, Lipids, C-Reactive Protein, Interleukin-6, and Fibrinogen: A Phase IIb Randomized, Placebo-Controlled Trial. Circulation 2012, 126, 2739–2748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ridker, P.M.; MacFadyen, J.G.; Thuren, T.; Everett, B.M.; Libby, P.; Glynn, R.J.; CANTOS Trial Group. Effect of Interleukin-1β Inhibition with Canakinumab on Incident Lung Cancer in Patients with Atherosclerosis: Exploratory Results from a Randomised, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Trial. Lancet 2017, 390, 1833–1842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ridker, P.M.; Devalaraja, M.; Baeres, F.M.M.; Engelmann, M.D.M.; Hovingh, G.K.; Ivkovic, M.; Lo, L.; Kling, D.; Pergola, P.; Raj, D.; et al. IL-6 Inhibition with Ziltivekimab in Patients at High Atherosclerotic Risk (RESCUE): A Double-Blind, Randomised, Placebo-Controlled, Phase 2 Trial. Lancet 2021, 397, 2060–2069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lachmann, H.J.; Kone-Paut, I.; Kuemmerle-Deschner, J.B.; Leslie, K.S.; Hachulla, E.; Quartier, P.; Gitton, X.; Widmer, A.; Patel, N.; Hawkins, P.N.; et al. Use of Canakinumab in the Cryopyrin-Associated Periodic Syndrome. N. Engl. J. Med. 2009, 360, 2416–2425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruperto, N.; Brunner, H.I.; Quartier, P.; Constantin, T.; Wulffraat, N.; Horneff, G.; Brik, R.; McCann, L.; Kasapcopur, O.; Rutkowska-Sak, L.; et al. Two Randomized Trials of Canakinumab in Systemic Juvenile Idiopathic Arthritis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2012, 367, 2396–2406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, B.; Zhang, Y.; Zhao, Z.; Ping, J.; Zhou, L.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, Y. Comparative Efficacy and Safety of Different Drugs in Patients with Systemic Juvenile Idiopathic Arthritis: A Systematic Review and Network Meta-Analysis. Medicine 2024, 103, e38002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abbate, A.; Wohlford, G.F.; Del Buono, M.G.; Chiabrando, J.G.; Markley, R.; Turlington, J.; Kadariya, D.; Trankle, C.R.; Biondi-Zoccai, G.; Lipinski, M.J.; et al. Interleukin-1 Blockade with Anakinra and Heart Failure Following ST-Segment Elevation Myocardial Infarction: Results from a Pooled Analysis of the VCUART Clinical Trials. Eur. Heart J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacother. 2022, 8, 503–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Denicolai, M.; Morello, M.; Golino, M.; Corna, G.; Del Buono, M.G.; Agatiello, C.R.; Van Tassell, B.W.; Abbate, A. Interleukin-1 Blockade in Patients with ST-Segment Elevation Myocardial Infarction Across the Spectrum of Coronary Artery Disease Complexity. J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacol. 2025, 85, 200–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abbate, A.; Kontos, M.C.; Grizzard, J.D.; Biondi-Zoccai, G.G.L.; Van Tassell, B.W.; Robati, R.; Roach, L.M.; Arena, R.A.; Roberts, C.S.; Varma, A.; et al. Interleukin-1 Blockade with Anakinra to Prevent Adverse Cardiac Remodeling after Acute Myocardial Infarction (Virginia Commonwealth University Anakinra Remodeling Trial [VCU-ART] Pilot Study). Am. J. Cardiol. 2010, 105, 1371–1377.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abbate, A.; Van Tassell, B.W.; Biondi-Zoccai, G.; Kontos, M.C.; Grizzard, J.D.; Spillman, D.W.; Oddi, C.; Roberts, C.S.; Melchior, R.D.; Mueller, G.H.; et al. Effects of Interleukin-1 Blockade with Anakinra on Adverse Cardiac Remodeling and Heart Failure after Acute Myocardial Infarction [from the Virginia Commonwealth University-Anakinra Remodeling Trial (2) (VCU-ART2) Pilot Study]. Am. J. Cardiol. 2013, 111, 1394–1400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abbate, A.; Trankle, C.R.; Buckley, L.F.; Lipinski, M.J.; Appleton, D.; Kadariya, D.; Canada, J.M.; Carbone, S.; Roberts, C.S.; Abouzaki, N.; et al. Interleukin-1 Blockade Inhibits the Acute Inflammatory Response in Patients With ST-Segment-Elevation Myocardial Infarction. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2020, 9, e014941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samsonov, M.; Bogin, V.; Van Tassell, B.W.; Abbate, A. Interleukin-1 Blockade with RPH-104 in Patients with Acute ST-Elevation Myocardial Infarction: Study Design and Rationale. J. Transl. Med. 2021, 19, 169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbate, A.; Van Tassell, B.; Bogin, V.; Markley, R.; Pevzner, D.V.; Cremer, P.C.; Meray, I.; Privalov, D.V.; Taylor, A.; Grishin, S.A.; et al. Results of International, Double-Blind, Randomized, Placebo-Controlled, Phase IIa Study of Interleukin-1 Blockade With RPH-104 (Goflikicept) in Patients With ST-Segment-Elevation Myocardial Infarction (STEMI). Circulation 2024, 150, 580–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Trial, Year | Patients (n) | Population Characteristics | Randomized Arms | Primary Endpoint | Main Results | Conclusions |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ODYSSEY OUTCOMES trial (2018) [113] | 18,924 | Patients who had ACS 1 to 12 months earlier, had LDL-C value ≥70 mg/dL, non-HDL ≥100 mg/dL or APOB ≥80 mg/dL, in HI statin therapy | To receive alirocumab or placebo every 2 weeks | A composite of death from coronary heart disease, nonfatal MI, fatal or nonfatal ischemic stroke, or unstable angina requiring hospitalization | A composite primary end-point event occurred in 903 patients (9.5%) in the alirocumab group and in 1052 patients (11.1%) in the placebo group (hazard ratio, 0.85; CI 95%, 0.78 to 0.93; p < 0.001) |

The risk of recurrent ischemic CV events was lower among those who received alirocumab than among those who received placebo |

| EPIC STEMI trial (2022) [114] | 68 | Patients with STEMI undergoing primary PCI | To receive alirocumab plus HI statin or placebo plus HI statin | Percentage of LDL-C reduction up to 6 weeks | LDL-C decreased by 72.9% with alirocumab versus 48.1% with the sham control, for a mean between-group difference of −22.3% (p < 0.001) | Alirocumab reduced LDL-C by 22% compared with sham control on a background of HI statin therapy |

| PACMAN-AMI trial (2022) [115] | 300 | Patients with acute MI undergoing primary PCI | To receive alirocumab plus HI statin or placebo plus HI statin | The change in IVUS-derived percent atheroma volume | At 52 weeks, mean change in percent atheroma volume was −2.13% with alirocumab vs. −0.92% with placebo (difference, −1.21%; CI 95%, −1.78% to −0.65%; p < 0.001) | The addition of subcutaneous biweekly alirocumab, compared with placebo, to HI statin therapy resulted in significantly greater coronary plaque regression in non-infarct-related arteries after 52 weeks |

| GAUSS-3 trial (2016) [116] | 511 | Patients with muscle-related statin intolerance | Phase A: used a 24 week crossover procedure with atorvastatin or placebo to identify patients having symptoms only with atorvastatin but not placebo. In phase B, after a 2-week washout, patients were randomized to ezetimibe or evolocumab for 24 weeks | Coprimary end points were the mean percent change in LDL-C level from baseline to the mean of weeks 22 and 24 levels and from baseline to week 24 levels | For the mean of weeks 22 and 24, LDL-C level with ezetimibe was 183.0 mg/dL; mean percent LDL-C change, −16.7% (95% CI, −20.5% to −12.9%), absolute change, −31.0 mg/dL and with evolocumab was 103.6 mg/dL; mean percent change, −54.5% (95% CI, −57.2% to −51.8%); absolute change, −106.8 mg/dL (p < 0.001). LDL-C level at week 24 with ezetimibe was 181.5 mg/dL; mean percent change, −16.7% (95% CI, −20.8% to −12.5%); absolute change, −31.2 mg/dL and with evolocumab was 104.1 mg/dL; mean percent change, −52.8% (95% CI, −55.8% to −49.8%); absolute change, −102.9 mg/dL (p< 0.001) | Among patients with statin intolerance related to muscle-related adverse effects, the use of evolocumab compared with ezetimibe resulted in a significantly greater reduction in LDL-C levels after 24 weeks |

| FOURIER trial (2017) [117] | 27,564 | Patients with ASCVD and LDL-C levels ≥70 mg/dL who were receiving statin therapy | To receive evolocumab or placebo | A composite of CV death, MI, stroke, hospitalization for unstable angina, or coronary revascularization | Evolocumab treatment significantly reduced the risk of the primary end point (1344 patients [9.8%] vs. 1563 patients [11.3%]; HR, 0.85; CI 95%, 0.79 to 0.92; p < 0.001) | Inhibition of PCSK9 with evolocumab on a background of statin therapy lowered LDL-C levels to a median of 30 mg per deciliter (0.78 mmol per liter) and reduced the risk of CV events |

| FOURIER sub-analysis (2018) [118] | 22,351 | Patients with a prior MI (most recent MI, number of prior MIs, and presence of residual multivessel CAD) | To receive evolocumab or placebo | A composite of CV death, MI, stroke, hospitalization for unstable angina, or coronary revascularization | Reduction of the primary endpoint of 20% (HR, 0.80; 95% CI, 0.71–0.91), 18% (HR, 0.82; 95% CI, 0.72–0.93), and 21% (HR, 0.79; 95% CI, 0.69–0.91) for those with more recent MI, multiple prior MIs, and residual multivessel CAD | Patients closer to their most recent MI, with multiple prior MIs, or with residual multivessel CAD are at high risk for MACEs and experience substantial risk reductions with LDL-C lowering with evolocumab |

| EVOPACS trial (2019) [119] | 308 | Patients hospitalized for ACS with elevated LDL-C levels | To receive evolocumab or placebo | Percentage change in calculated LDL-C over 8 weeks | Mean LDL-C levels decreased from 3.61 to 0.79 mmol/l at week 8 in the evolocumab group, and from 3.42 to 2.06 mmol/l in the placebo group; the difference in mean percentage change from baseline was 40.7% (CI 95%: 45.2 to 36.2; p < 0.001) | Evolocumab added to HI statin therapy was well tolerated and resulted in substantial reduction in LDL-C levels, rendering >95% of patients within currently recommended target levels |