Mechanisms of Intracranial Aneurysm Rupture: An Integrative Review of Experimental and Clinical Evidence

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Knowledge of Mechanisms That Lead to Rupture

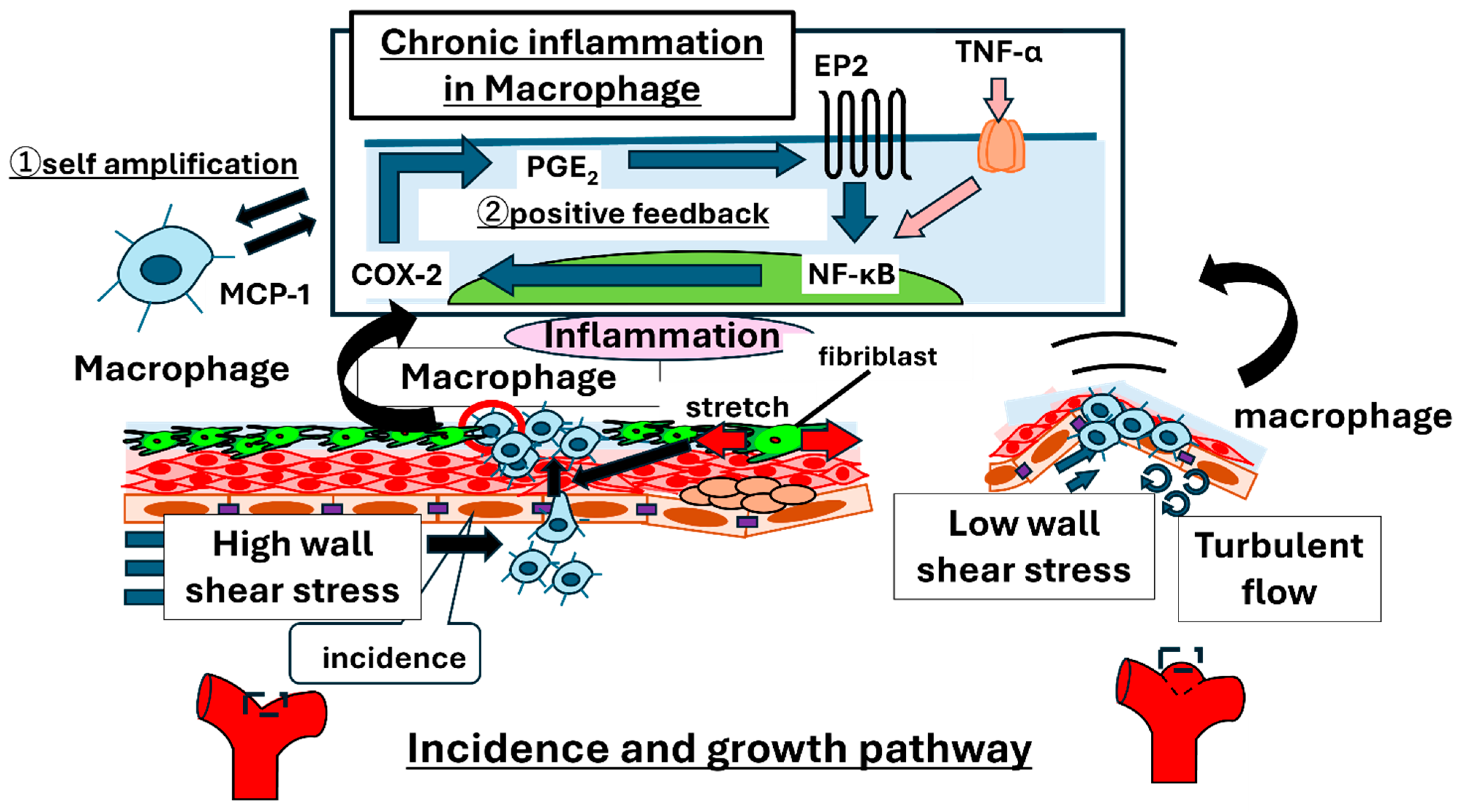

2.1. Overview of Mechanisms of Aneurysm Initiation and Growth

2.2. Recent Insights into Mechanisms of IA Rupture

3. Clinical Implications of Defining IAs as a Chronic Inflammatory Disease

4. Clinical Evidence from Cohorts

4.1. Patient-Level Factors

4.2. Risk Scores and Clinical Judgment

5. Clinical Imaging & Quantitative Biomarkers

5.1. Vessel-Wall MRI (VWI)

5.2. Shape and Hemodynamics (Clinically Usable Markers)

5.3. Wall Motion of IAs

5.4. Radiomics and AI

6. Translational Clinical Implications

6.1. Risk Stratification Pathway (At the Hospital Level)

6.2. Surveillance Design

6.3. Therapeutic Directions

7. Clinical Therapy

8. Gene-Editing Therapy

8.1. Preclinical Proof-of-Concept (SOX17-CRISPRa)

8.2. Human Genetic and Functional Rationale for SOX17 Targeting

9. Limitation and Future Direction

10. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Duan, J.; Zhao, Q.; He, Z. Current Understanding of Macrophages in Intracranial Aneurysm: Relevant Etiological Manifestations, Signaling Modulation and Therapeutic Strategies. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1320098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, H.; Luo, Y.; Zuo, Q. Current Understanding of the Molecular Mechanism between Hemodynamic- Induced Intracranial Aneurysm and Inflammation. Curr. Protein Pept. Sci. 2019, 20, 789–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frosen, J.; Cebral, J.; Robertson, A.M. Flow-Induced, Inflammation-Mediated Arterial Wall Remodeling in the Formation and Progression of Intracranial Aneurysms. Neurosurg. Focus. 2019, 47, E21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muhammad, S.; Chaudhry, S.R.; Dobreva, G. Vascular Macrophages as Therapeutic Targets to Treat Intracranial Aneurysms. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 630381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Signorelli, F.; Sela, S.; Gesualdo, L. Hemodynamic Stress, Inflammation, and Intracranial Aneurysm Development and Rupture: A Systematic Review. World Neurosurg. 2018, 115, 234–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aoki, T.; Kataoka, H.; Ishibashi, R. Impact of Monocyte Chemoattractant Protein-1 Deficiency on Cerebral Aneurysm Formation. Stroke 2009, 40, 942–951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aoki, T.; Nishimura, M.; Matsuoka, T. Pge(2)-Ep(2) Signalling in Endothelium Is Activated by Haemodynamic Stress and Induces Cerebral Aneurysm through an Amplifying Loop Via Nf-Kappab. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2011, 163, 1237–1249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aoki, T.; Shimizu, K.; Yamamoto, N. Mechanobiology of Intracranial Aneurysms (Chapter: Diseases Involving Mechanical Stress—Cardiovascular/Respiratory). Exp. Med. 2020, 38, 1096–1104. [Google Scholar]

- Aoki, T.; Frosen, J.; Fukuda, M. Prostaglandin E2-Ep2-Nf-Kappab Signaling in Macrophages as a Potential Therapeutic Target for Intracranial Aneurysms. Sci. Signal 2017, 10, eaah6037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aoki, T.; Kataoka, H.; Morimoto, M. Macrophage-Derived Matrix Metalloproteinase-2 and -9 Promote the Progression of Cerebral Aneurysms in Rats. Stroke 2007, 38, 162–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimizu, K.; Kushamae, M.; Mizutani, T. Intracranial Aneurysm as a Macrophage-Mediated Inflammatory Disease. Neurol. Med. Chir. 2019, 59, 126–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanematsu, Y.; Kanematsu, M.; Kurihara, C. Critical Roles of Macrophages in the Formation of Intracranial Aneurysm. Stroke 2011, 42, 173–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koseki, H.; Miyata, H.; Shimo, S. Two Diverse Hemodynamic Forces, a Mechanical Stretch and a High Wall Shear Stress, Determine Intracranial Aneurysm Formation. Transl. Stroke Res. 2020, 11, 80–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukuda, M.; Fukuda, S.; Ando, J. Disruption of P2x4 Purinoceptor and Suppression of the Inflammation Associated with Cerebral Aneurysm Formation. J. Neurosurg. 2019, 134, 102–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oka, M.; Shimo, S.; Ohno, N. Dedifferentiation of Smooth Muscle Cells in Intracranial Aneurysms and Its Potential Contribution to the Pathogenesis. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 8330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aoki, T.; Yamamoto, K.; Fukuda, M. Sustained Expression of Mcp-1 by Low Wall Shear Stress Loading Concomitant with Turbulent Flow on Endothelial Cells of Intracranial Aneurysm. Acta Neuropathol. Commun. 2016, 4, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, H.; Wang, G.; Tian, Q. Low Shear Stress Induces Macrophage Infiltration and Aggravates Aneurysm Wall Inflammation Via Ccl7/Ccr1/Tak1/ Nf-Kappab Axis. Cell Signal 2024, 117, 111122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aoki, T.; Saito, M.; Koseki, H. Macrophage Imaging of Cerebral Aneurysms with Ferumoxytol: An Exploratory Study in an Animal Model and in Patients. J. Stroke Cerebrovasc. Dis. 2017, 26, 2055–2064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wermer, M.J.; van der Schaaf, I.C.; Algra, A. Risk of Rupture of Unruptured Intracranial Aneurysms in Relation to Patient and Aneurysm Characteristics: An Updated Meta-Analysis. Stroke 2007, 38, 1404–1410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morita, A.; Kirino, T.; Hashi, K. The Natural Course of Unruptured Cerebral Aneurysms in a Japanese Cohort. N. Engl. J. Med. 2012, 366, 2474–2482. [Google Scholar]

- Greving, J.P.; Wermer, M.J.; Brown, R.D., Jr. Development of the Phases Score for Prediction of Risk of Rupture of Intracranial Aneurysms: A Pooled Analysis of Six Prospective Cohort Studies. Lancet Neurol. 2014, 13, 59–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyamoto, T.; Kung, D.K.; Kitazato, K.T. Site-Specific Elevation of Interleukin-1beta and Matrix Metalloproteinase-9 in the Willis Circle by Hemodynamic Changes Is Associated with Rupture in a Novel Rat Cerebral Aneurysm Model. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 2017, 37, 2795–2805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kushamae, M.; Miyata, H.; Shirai, M. Involvement of Neutrophils in Machineries Underlying the Rupture of Intracranial Aneurysms in Rats. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 20004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyata, H.; Imai, H.; Koseki, H. Vasa Vasorum Formation Is Associated with Rupture of Intracranial Aneurysms. J. Neurosurg. 2019, 133, 789–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ono, I.; Kayahara, T.; Kawashima, A. Hypoxic Microenvironment as a Crucial Factor Triggering Events Leading to Rupture of Intracranial Aneurysm. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 5545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chytte, D.; Bruno, G.; Desai, S. Inflammation and Intracranial Aneurysms. Neurosurgery 1999, 45, 1137–1146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kataoka, K.; Taneda, M.; Asai, T. Structural Fragility and Inflammatory Response of Ruptured Cerebral Aneurysms. Stroke 1999, 30, 1396–1401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frosen, J.; Piippo, A.; Paetau, A. Remodeling of Saccular Cerebral Artery Aneurysm Wall Is Associated with Rupture: Histological Analysis of 24 Unruptured and 42 Ruptured Cases. Stroke 2004, 35, 2287–2293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cannizzaro, D.; Zaed, I.; Olei, S. Growth and Rupture of an Intracranial Aneurysm: The Role of Wall Aneurysmal Enhancement and Cd68. Front. Surg. 2023, 10, 1228955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stratilova, M.H.; Koblizek, M.; Steklacova, A. Increased Macrophage M2/M1 Ratio Is Associated with Intracranial Aneurysm Rupture. Acta Neurochir. 2023, 165, 177–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hasan, D.M.; Chalouhi, N.; Jabbour, P. Imaging Aspirin Effect on Macrophages in the Wall of Human Cerebral Aneurysms Using Ferumoxytol-Enhanced Mri: Preliminary Results. J. Neuroradiol. 2013, 40, 187–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ollikainen, E.; Tulamo, R.; Frosen, J. Mast Cells, Neovascularization, and Microhemorrhages Are Associated with Saccular Intracranial Artery Aneurysm Wall Remodeling. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 2014, 73, 855–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawakatsu, T.; Kamio, Y.; Makino, H. Dietary Iron Restriction Protects against Aneurysm Rupture in a Mouse Model of Intracranial Aneurysm. Cerebrovasc. Dis. 2023, 53, 191–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez, A.N.; Tortelote, G.G.; Pascale, C.L. Single-Cell Transcriptome Analysis of the Circle of Willis in a Mouse Cerebral Aneurysm Model. Stroke 2022, 53, 2647–2657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skirgaudas, M.; Awad, I.A.; Kim, J. Expression of Angiogenesis Factors and Selected Vascular Wall Matrix Proteins in Intracranial Saccular Aneurysms. Neurosurgery 1996, 39, 537–545. [Google Scholar]

- Han, Y.; Li, G.; Zhang, Z. Axl Promotes Intracranial Aneurysm Rupture by Regulating Macrophage Polarization toward M1 Via Stat1/Hif-1alpha. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1158758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okada, A.; Shimizu, K.; Kawashima, A. C5a-C5ar1 Axis as a Potential Trigger of the Rupture of Intracranial Aneurysms. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 3105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harvath, L. Neutrophil Chemotactic Factors. Cell Motil. Factors 1991, 59, 35–52. [Google Scholar]

- Clower, B.R.; Sullivan, D.M.; Smith, R.R. Intracranial Vessels Lack Vasa Vasorum. J. Neurosurg. 1984, 61, 44–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aoki, T.; Koseki, H.; Miyata, H. Understanding Intracranial Aneurysms through Inflammation. Neurol. Surg. 2018, 46, 275–294. [Google Scholar]

- Can, A.; Castro, V.M.; Dligach, D. Lipid-Lowering Agents and High Hdl (High-Density Lipoprotein) Are Inversely Associated with Intracranial Aneurysm Rupture. Stroke 2018, 49, 1148–1154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimizu, K.; Imamura, H.; Tani, S. Candidate Drugs for Preventive Treatment of Unruptured Intracranial Aneurysms: A Cross-Sectional Study. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0246865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, D.; Chalouhi, N.; Jabbour, P. Macrophage Imbalance (M1 Vs. M2) and upregulation of mast cells in wall of ruptured human cerebral aneurysms: Preliminary results. J. Neuroinflamm. 2012, 9, 222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saqr, K.M.; Rashad, S.; Tupin, S. What Does Computational Fluid Dynamics Tell Us About Intracranial Aneurysms? A Meta-Analysis and Critical Review. J. Cereb. Blood Flow. Metab. 2020, 40, 1021–1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murayama, Y.; Fujimura, S.; Suzuki, T. Computational Fluid Dynamics as a Risk Assessment Tool for Aneurysm Rupture. Neurosurg. Focus 2019, 47, E12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vlak, M.H.; Algra, A.; Brandenburg, R. Prevalence of Unruptured Intracranial Aneurysms, with Emphasis on Sex, Age, Comorbidity, Country, and Time Period: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Lancet Neurol. 2011, 10, 626–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Backes, D.; Rinkel, G.J.E.; Greving, J.P.; Velthuis, B.K.; Murayama, Y.; Takao, H.; Ishibashi, T.; Igase, M.; Terbrugge, K.G.; Agid, R.; et al. Elapss Score for Prediction of Risk of Growth of Unruptured Intracranial Aneurysms. Neurology 2017, 88, 1600–1606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sánchez van Kammen, M.; Greving, J.P.; Kuroda, S.; Kashiwazaki, D.; Morita, A.; Shiokawa, Y.; Kimura, T.; Cognard, C.; Januel, A.C.; Lindgren, A.; et al. External Validation of the Elapss Score for Prediction of Unruptured Intracranial Aneurysm Growth Risk. J. Stroke 2019, 21, 340–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Kamp, L.T.; Rinkel, G.J.E.; Verbaan, D.; van den Berg, R.; Vandertop, W.P.; Murayama, Y.; Ishibashi, T.; Lindgren, A.; Koivisto, T.; Teo, M.; et al. Risk of Rupture after Intracranial Aneurysm Growth. JAMA Neurol. 2021, 78, 1228–1235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sonobe, M.; Yamamura, A.; Nakazawa, K.; Togashi, K. Small Unruptured Intracranial Aneurysm Verification (Suave) Study: Risk of Rupture of Small Unruptured Cerebral Aneurysms. Stroke 2010, 41, 1969–1977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hallikainen, J.; Lindgren, A.; Savolainen, J. Periodontitis and Gingival Bleeding Associate with Intracranial Aneurysms and Risk of Aneurysmal Subarachnoid Hemorrhage. Neurosurg. Rev. 2020, 43, 669–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Gijn, J.; Kerr, R.S.; Rinkel, G.J. Subarachnoid Haemorrhage. Lancet 2007, 369, 306–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawton, M.T.; Vates, G.E. Subarachnoid Hemorrhage. N. Engl. J. Med. 2017, 377, 257–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haemmerli, J.; Morel, S.; Georges, M. Characteristics and Distribution of Intracranial Aneurysms in Patients with Autosomal Dominant Polycystic Kidney Disease Compared with the General Population: A Meta-Analysis. Kidney360 2023, 4, e466–e475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yen, P.W.; Chen, Y.A.; Wang, W. The Screening, Diagnosis, and Management of Patients with Autosomal Dominant Polycystic Kidney Disease: A National Consensus Statement from Taiwan. Nephrology 2024, 29, 245–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rinkel, G.J.; Djibuti, M.; Algra, A. Prevalence and Risk of Rupture of Intracranial Aneurysms: A Systematic Review. Stroke 1998, 29, 251–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Etminan, N.; Brown, R.D., Jr.; Beseoglu, K.; Juvela, S.; Raymond, J.; Morita, A.; Torner, J.C.; Derdeyn, C.P.; Raabe, A.; Mocco, J.; et al. The Unruptured Intracranial Aneurysm Treatment Score: A Multidisciplinary Consensus. Neurology 2015, 85, 881–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shimizu, K.; Kushamae, M.; Aoki, T. Macrophage Imaging of Intracranial Aneurysms. Neurol. Med. Chir. 2019, 59, 257–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.-Q.; Meng, Z.-H.; Hou, Z.-J.; Huang, S.-Q.; Chen, J.-N.; Yu, H.; Feng, L.-J.; Wang, Q.-J.; Li, P.-A.; Wen, Z.-B. Geometric Parameter Analysis of Ruptured and Unruptured Intracranial Aneurysms. AJNR Am. J. Neuroradiol. 2016, 37, 1413–1417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalsoum, E.; Hassen, W.B.; Boulouis, G.; Hassen, M.B.; Trystram, D.; Marro, B.; Edjlali, M.; Meder, J.F.; Oppenheim, C. Blood Flow Mimicking Aneurysmal Wall Enhancement in Intracranial Aneurysms. AJNR Am. J. Neuroradiol. 2018, 39, 1065–1071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Yan, C.; Yuan, W.; Jiang, S.; Jiang, Y.; Chen, T. Enhancing Intracranial Aneurysm Rupture Risk Prediction with a Novel Multivariable Logistic Regression Model Incorporating High-Resolution Vessel Wall Imaging. Front. Neurol. 2024, 15, 1507082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, W.; Jiang, S.; Wang, Z.; Yan, C.; Jiang, Y.; Guo, D.; Chen, T. High-Resolution Vessel Wall Imaging-Driven Radiomic Analysis for the Precision Prediction of Intracranial Aneurysm Rupture Risk: A Promising Approach. Front. Neurosci. 2025, 19, 1581373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Kamp, L.T.; Vergouwen, M.D.I.; Etminan, N. Gadolinium-Enhanced Intracranial Aneurysm Wall Imaging in Clinical Practice: Where Do We Stand? Eur. Radiol. 2024, 34, 4610–4618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leon-Rojas, J.E. Beyond Size: Advanced Mri Breakthroughs in Predicting Intracranial Aneurysm Rupture Risk. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 3158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamphuis, M.J.; van der Kamp, L.T.; Lette, E.; Rinkel, G.J.E.; Vergouwen, M.D.I.; van der Schaaf, I.C.; de Jong, P.A.; Ruigrok, Y.M. Intracranial Arterial Calcification in Patients with Unruptured and Ruptured Intracranial Aneurysms. Eur. Radiol. 2024, 34, 7517–7525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, S.; Wang, X. Advanced Mr Techniques for the Vessel Wall: Towards a Better Assessment of Intracranial Aneurysm Instability. Eur. Radiol. 2024, 34, 5201–5203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashimoto, Y.; Matsushige, T.; Kawano, R.; Shimonaga, K.; Yoshiyama, M.; Takahashi, H.; Kaneko, M.; Ono, C.; Sakamoto, S. Segmentation of Aneurysm Wall Enhancement in Evolving Unruptured Intracranial Aneurysms. J. Neurosurg. 2022, 136, 449–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mandell, D.M.; Mossa-Basha, M.; Qiao, Y.; Hess, C.P.; Hui, F.; Matouk, C.; Johnson, M.H.; Daemen, M.J.; Vossough, A.; Edjlali, M.; et al. Intracranial Vessel Wall Mri: Principles and Expert Consensus Recommendations of the American Society of Neuroradiology. AJNR Am. J. Neuroradiol. 2017, 38, 218–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rahman, M.; Smietana, J.; Haughn, C.; Hoh, B.; Hopkins, N.; Siddiqui, A.; Levy, E.I.; Meng, H.; Mocco, J. Size Ratio Correlates with Intracranial Aneurysm Rupture Status: A Prospective Study. Stroke 2010, 41, 916–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aoki, T.; Kataoka, H.; Shimamura, M. Nf-Kappab Is a Key Mediator of Cerebral Aneurysm Formation. Circulation 2007, 116, 2830–2840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimizu, K.; Kataoka, H.; Imai, H. Hemodynamic Force as a Potential Regulator of Inflammation-Mediated Focal Growth of Saccular Aneurysms in a Rat Model. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 2021, 80, 79–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, G.; Zhu, Y.; Yin, Y.; Su, M.; Li, M. Association of Wall Shear Stress with Intracranial Aneurysm Rupture: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 5331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orr, A.W.; Sanders, J.M.; Bevard, M.; Coleman, E.; Sarembock, I.J.; Schwartz, M.A. The Subendothelial Extracellular Matrix Modulates Nf-Kappab Activation by Flow: A Potential Role in Atherosclerosis. J. Cell Biol. 2005, 169, 191–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lan, Q.; Mercurius, K.O.; Davies, P.F. Stimulation of Transcription Factors Nf Kappa B and Ap1 in Endothelial Cells Subjected to Shear Stress. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1994, 201, 950–956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khachigian, L.M.; Resnick, N.; Gimbrone, M.A., Jr.; Collins, T. Nuclear Factor-Kappa B Interacts Functionally with the Platelet-Derived Growth Factor B-Chain Shear-Stress Response Element in Vascular Endothelial Cells Exposed to Fluid Shear Stress. J. Clin. Investig. 1995, 96, 1169–1175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballermann, B.J.; Dardik, A.; Eng, E.; Liu, A. Shear Stress and the Endothelium. Kidney Int. Suppl. 1998, 67, S100–S108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cooper, A.P. Lectures on the Principles and Practice of Surgery; Edward Portwine: London, UK; John Thomas Cox: London, UK, 1835. [Google Scholar]

- Cushing, H.I. The Control of Bleeding in Operations for Brain Tumors: With the Description of Silver “Clips” for the Occlusion of Vessels Inaccessible to the Ligature. Ann. Surg. 1911, 54, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raabe, A.; Beck, J.; Gerlach, R.; Zimmermann, M.; Seifert, V. Near-Infrared Indocyanine Green Video Angiography: A New Method for Intraoperative Assessment of Vascular Flow. Neurosurgery 2003, 52, 132–139, discussion 139. [Google Scholar]

- Zhong, J.; Jiang, Y.; Huang, Q.; Yang, S. Diagnostic and Predictive Value of Radiomics-Based Machine Learning for Intracranial Aneurysm Rupture Status: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Neurosurg. Rev. 2024, 47, 845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsen, N.; von der Brelie, C.; Lelke, M.; Saering, D.; Madjidyar, J.; Jungbluth, P.; Jansen, O.; Synowitz, M. Vessel Wall Enhancement in Unruptured Intracranial Aneurysms: Associations with Aneurysm Instability. AJNR Am. J. Neuroradiol. 2018, 39, 1617–1621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edjlali, M.; Guédon, A.; Boulouis, G.; Hassen, W.B.; Trystram, D.; Rodallec, M.; Naggara, O.; Meder, J.F.; Oppenheim, C. Circumferential Thick Enhancement at Vessel Wall Mri Has High Specificity for Unstable Unruptured Intracranial Aneurysms. Radiology 2018, 289, 181–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Debrun, G.; Lacour, P.; Caron, J.P.; Hurth, M.; Comoy, J.; Keravel, Y. Detachable Balloon and Calibrated-Leak Balloon Techniques in the Treatment of Cerebral Vascular Lesions. J. Neurosurg. 1978, 49, 635–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monsein, L.H. New Detachable Coils for Treating Cerebral Aneurysms. Nat. Med. 1996, 2, 160–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higashida, R.T.; Smith, W.; Gress, D.; Urwin, R.; Dowd, C.F.; Balousek, P.A.; Halbach, V.V. Intravascular Stent and Endovascular Coil Placement for a Ruptured Fusiform Aneurysm of the Basilar Artery. Case Report and Review of the Literature. J. Neurosurg. 1997, 87, 944–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, P.K.; Lylyk, P.; Szikora, I.; Wetzel, S.G.; Wanke, I.; Fiorella, D. The Pipeline Embolization Device for the Intracranial Treatment of Aneurysms Trial. AJNR Am. J. Neuroradiol. 2011, 32, 34–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Y.H.; Lewis, D.A.; Kadirvel, R.; Dai, D.; Kallmes, D.F. The Woven Endobridge: A New Aneurysm Occlusion Device. AJNR Am. J. Neuroradiol. 2011, 32, 607–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabelo, N.N.; Telles, J.P.M.; Pipek, L.Z.; Makarem, L.; Boechat, A.L.; Teixeira, M.J.; Figueiredo, E.G. Long-Term Outcomes of Ruptured Saccular Intracranial Aneurysm Clipping Versus Coiling: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Neurol. Sci. 2022, 43, 4909–4915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boisseau, W.; Darsaut, T.E.; Fahed, R.; Drake, B.; Lesiuk, H.; Rempel, J.L.; Gentric, J.C.; Ognard, J.; Nico, L.; Iancu, D.; et al. Stent-Assisted Coiling in the Treatment of Unruptured Intracranial Aneurysms: A Randomized Clinical Trial. AJNR Am. J. Neuroradiol. 2023, 44, 381–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hetts, S.W.; Turk, A.; English, J.D.; Dowd, C.F.; Mocco, J.; Prestigiacomo, C.; Nesbit, G.; Ge, S.G.; Jin, J.N.; Carroll, K.; et al. Stent-Assisted Coiling Versus Coiling Alone in Unruptured Intracranial Aneurysms in the Matrix and Platinum Science Trial: Safety, Efficacy, and Mid-Term Outcomes. AJNR Am. J. Neuroradiol. 2014, 35, 698–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Becske, T.; Potts, M.B.; Shapiro, M.; Kallmes, D.F.; Brinjikji, W.; Saatci, I.; McDougall, C.G.; Szikora, I.; Lanzino, G.; Moran, C.J.; et al. Pipeline for Uncoilable or Failed Aneurysms: 3-Year Follow-up Results. J. Neurosurg. 2017, 127, 81–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sahlein, D.H.; Fouladvand, M.; Becske, T.; Saatci, I.; McDougall, C.G.; Szikora, I.; Lanzino, G.; Moran, C.J.; Woo, H.H.; Lopes, D.K.; et al. Neuroophthalmological Outcomes Associated with Use of the Pipeline Embolization Device: Analysis of the Pufs Trial Results. J. Neurosurg. 2015, 123, 897–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hanel, R.A.; Kallmes, D.F.; Lopes, D.K.; Nelson, P.K.; Siddiqui, A.; Jabbour, P.; Pereira, V.M.; István, I.S.; Zaidat, O.O.; Bettegowda, C.; et al. Prospective Study on Embolization of Intracranial Aneurysms with the Pipeline Device: The Premier Study 1 Year Results. J. NeuroInterv. Surg. 2020, 12, 62–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leung, G.K.; Tsang, A.C.; Lui, W.M. Pipeline Embolization Device for Intracranial Aneurysm: A Systematic Review. Clin. Neuroradiol. 2012, 22, 295–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moran, C.J. The Collar Sign in Pipeline Embolization Device-Treated Aneurysms. AJNR Am. J. Neuroradiol. 2020, 41, 486–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiorella, D.; Molyneux, A.; Coon, A.; Szikora, I.; Saatci, I.; Baltacioglu, F.; Aziz-Sultan, M.A.; Hoit, D.; Almandoz, J.E.D.; Elijovich, L.; et al. Safety and Effectiveness of the Woven Endobridge (Web) System for the Treatment of Wide Necked Bifurcation Aneurysms: Final 5 Year Results of the Pivotal Web Intra-Saccular Therapy Study (Web-It). J. NeuroInterv. Surg. 2023, 15, 1175–1180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goertz, L.; Liebig, T.; Siebert, E.; Dorn, F.; Pflaeging, M.; Forbrig, R.; Pennig, L.; Schlamann, M.; Kabbasch, C. Long-Term Clinical and Angiographic Outcome of the Woven Endobridge (Web) for Endovascular Treatment of Intracranial Aneurysms. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 11467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goertz, L.; Liebig, T.; Siebert, E.; Zopfs, D.; Pennig, L.; Pflaeging, M.; Schlamann, M.; Radomi, A.; Dorn, F.; Kabbasch, C. Lessons Learned from 12 Years Using the Woven Endobridge for the Treatment of Cerebral Aneurysms in a Multi-Center Series. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 24212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, D.; Yuan, Y.; Long, P.; Huang, J.; Jiang, M.; Tang, Y.; Luo, Y.; Zhang, C.; Zheng, P.; Yang, L.; et al. Targeted Gene Therapy for Intracranial Aneurysm Using Sox17-Crispra. Chem. Eng. J. 2025, 521, 166492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasuno, K.; Bilguvar, K.; Bijlenga, P.; Low, S.K.; Krischek, B.; Auburger, G.; Simon, M.; Krex, D.; Arlier, Z.; Nayak, N.; et al. Genome-Wide Association Study of Intracranial Aneurysm Identifies Three New Risk Loci. Nat. Genet. 2010, 42, 420–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schröder, L.C.; Hüttermann, L.; Remes, A.K.; Voran, J.C.; Hille, S.; Sommer, W.; Lutter, G.; Warnecke, G.; Frank, D.; Schade, D.; et al. Aav Library Screening Identifies Novel Vector for Efficient Transduction of Human Aorta. Gene Ther. 2025, 32, 154–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McAvoy, M.; Ratner, B.; Ferreira, M.J.; Levitt, M.R. Gene Therapy for Intracranial Aneurysms: Systemic Review. J. NeuroInterv. Surg. 2025, 17, 859–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Category | Milestone/Device (Year) | Key Features and Advances | Advantages | Limitations/Notes | Key References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Microsurgical approaches | Proximal ligation (1748) | First reported ligation of a cerebral aneurysm. | Historical origin of direct surgical repair. | Non-selective, high morbidity. | [86] |

| Clipping technique (1911) | Introduction of aneurysm neck clipping; foundation of modern surgery. | Durable complete occlusion (>90%). | Invasive; technically demanding. | [87] | |

| Intraoperative fluorescence angiography (2003) | Real-time confirmation of vascular patency and occlusion. | Improved safety and accuracy. | Limited to open surgery. | [88] | |

| Endoscopic-assisted clipping (2006) | First reported use of endoscope for visualization in clipping surgery. | Better visualization of deep/bifurcation lesions. | Requires microsurgical expertise. | [88] | |

| Endovascular interventions | Detachable balloon embolization (1978) | First endovascular occlusion method. | Pioneering minimally invasive concept. | Technically limited; risk of migration. | [89] |

| Coil embolization (1990) | Introduction of detachable coils (Guglielmi). | Minimally invasive; shorter hospital stay; lower perioperative risk. | Higher recurrence/recanalization rates. | [90] | |

| Stent-assisted coiling (SAC, 1997) | Use of stents to support coil packing in wide-neck aneurysms. | Expanded indications to complex aneurysms; stable packing. | Dual antiplatelet therapy required; not ideal for ruptured cases. | [89,90] | |

| Flow diverter (FD, 2008, Pipeline Embolization Device [PED]) | Paradigm shift to parent-vessel reconstruction. | Complete occlusion 76–85% at 1 year (PUFS, PREMIER); low retreatment (~5%). | Procedure-related risk <6%; limited initially to large sidewall aneurysms. | [91,92,93,94,95] | |

| Intrasaccular flow disruption (WEB, 2011) | Woven EndoBridge device for bifurcation aneurysms. | Effective occlusion (~80% at 5 years); no long-term dual antiplatelet therapy needed. | Limited to specific morphologies; ongoing device refinement. | [96,97,98] | |

| Current direction | - | Integration of morphology, VWI, and hemodynamics for individualized, anatomy-tailored therapy. | Multidisciplinary optimization of treatment choice. | - | - |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Itani, M.; Aoki, T. Mechanisms of Intracranial Aneurysm Rupture: An Integrative Review of Experimental and Clinical Evidence. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 8256. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14228256

Itani M, Aoki T. Mechanisms of Intracranial Aneurysm Rupture: An Integrative Review of Experimental and Clinical Evidence. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(22):8256. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14228256

Chicago/Turabian StyleItani, Masahiko, and Tomohiro Aoki. 2025. "Mechanisms of Intracranial Aneurysm Rupture: An Integrative Review of Experimental and Clinical Evidence" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 22: 8256. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14228256

APA StyleItani, M., & Aoki, T. (2025). Mechanisms of Intracranial Aneurysm Rupture: An Integrative Review of Experimental and Clinical Evidence. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(22), 8256. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14228256