Balancing Safety and Efficacy: Factor XIa INHIBITORS vs. DOACs in Patients with Atrial Fibrillation: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials †

Abstract

1. Introduction

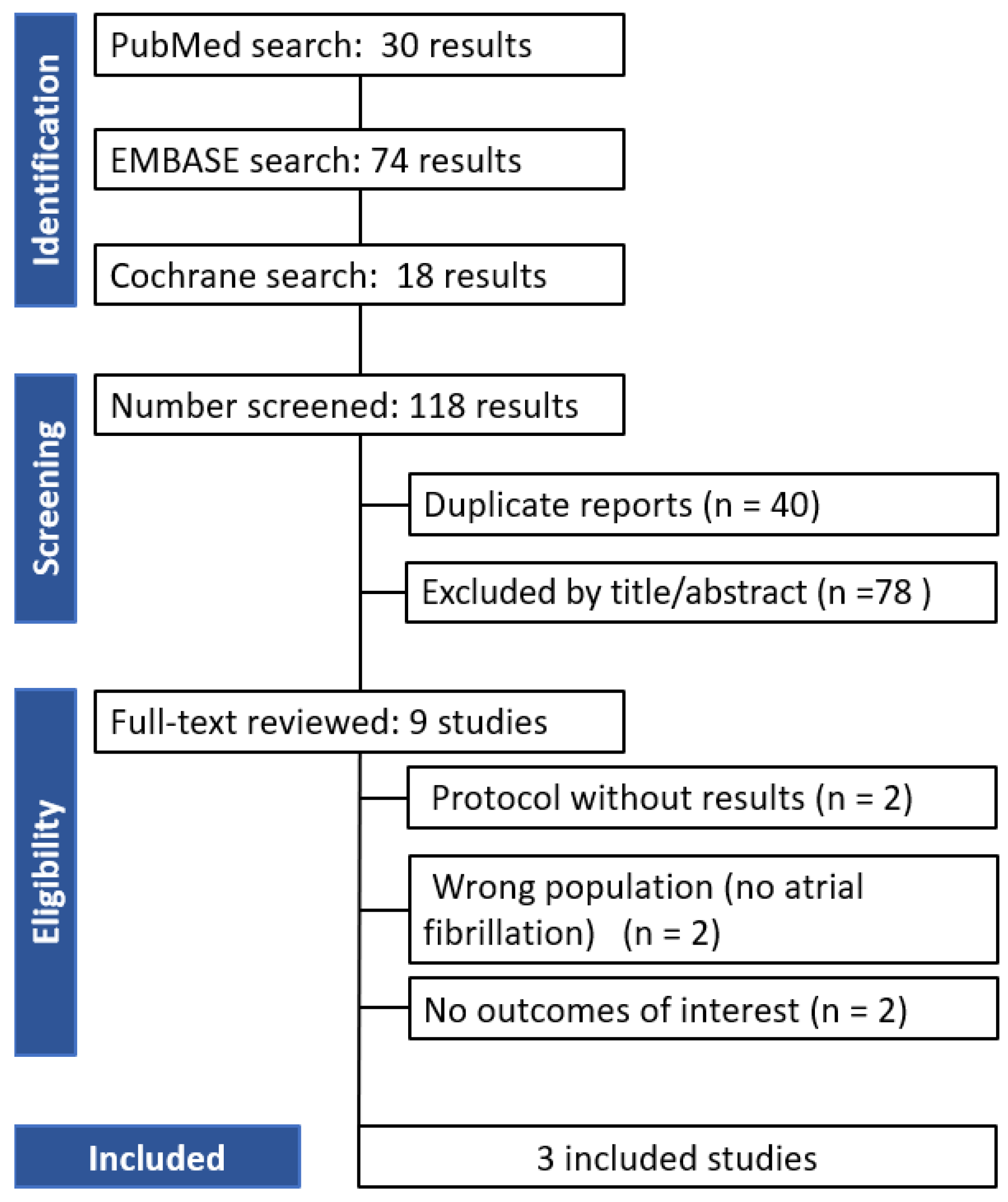

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Search Strategy

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

2.3. Screening and Data Extraction

2.4. Quality Assessment

2.5. Statistical Analysis

2.6. Study Endpoints

3. Results

3.1. Qualitative Analysis

3.2. Risk of Bias Assessment

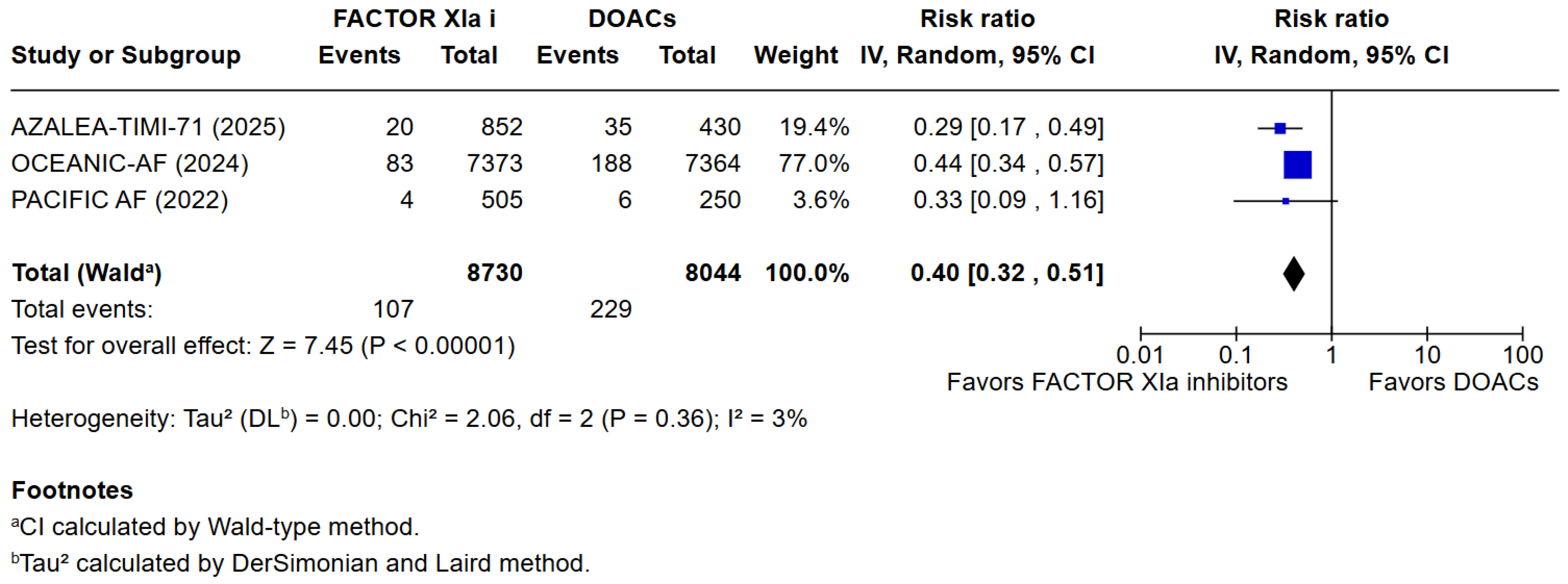

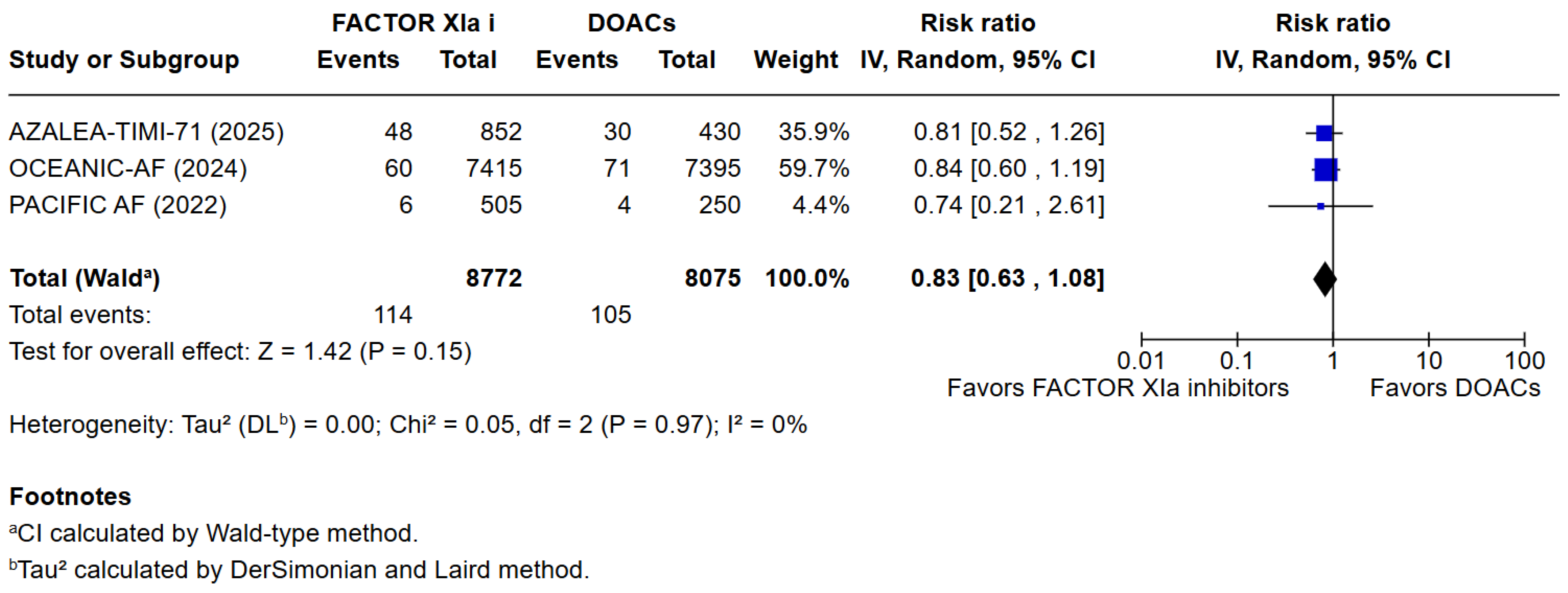

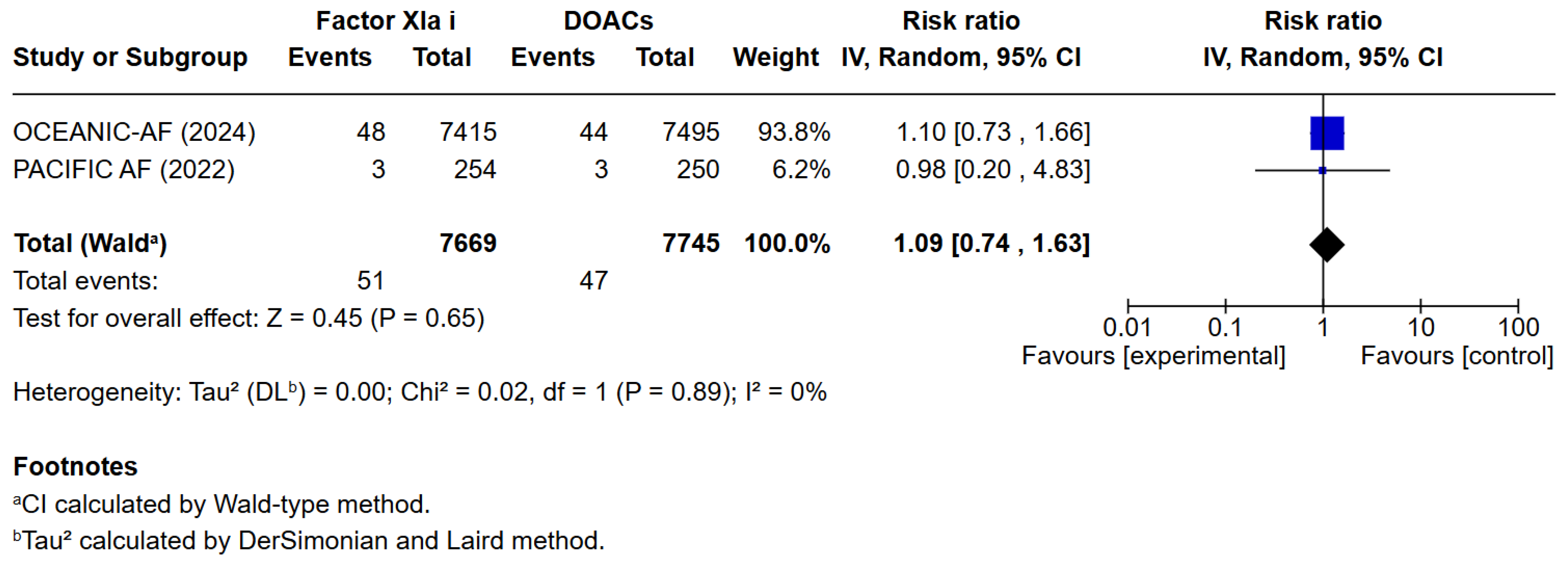

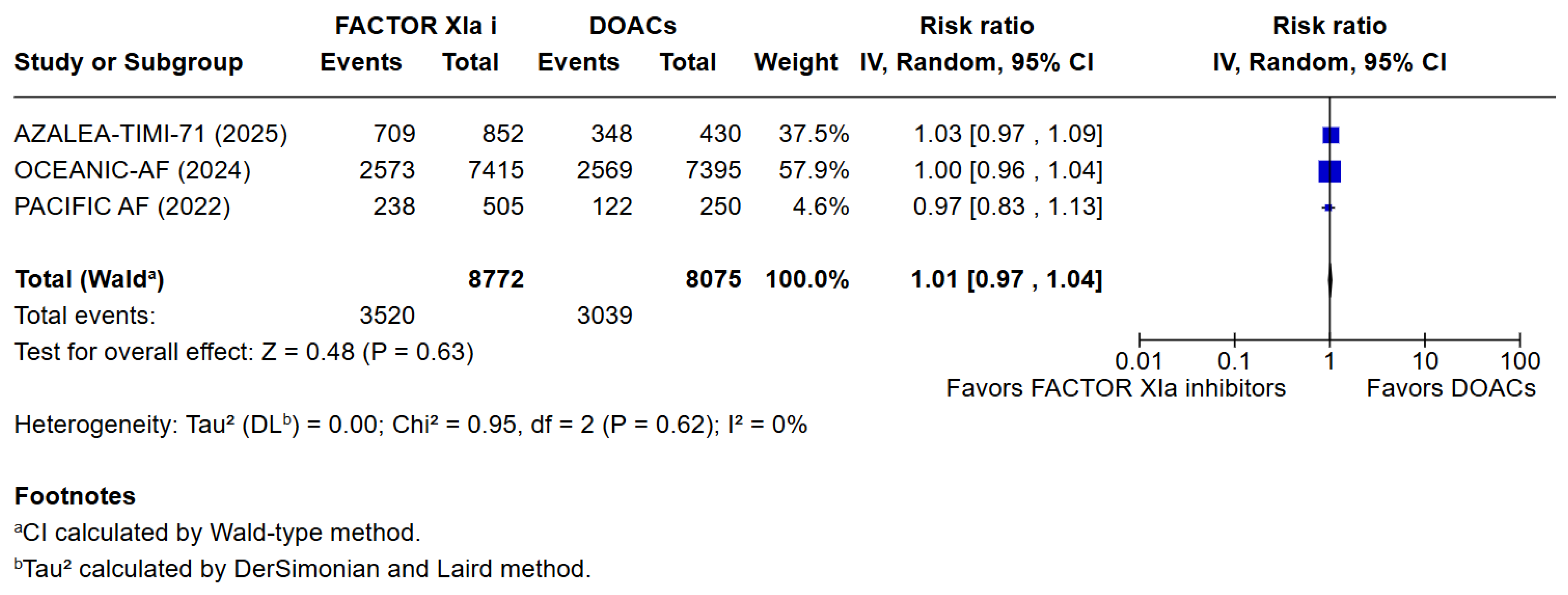

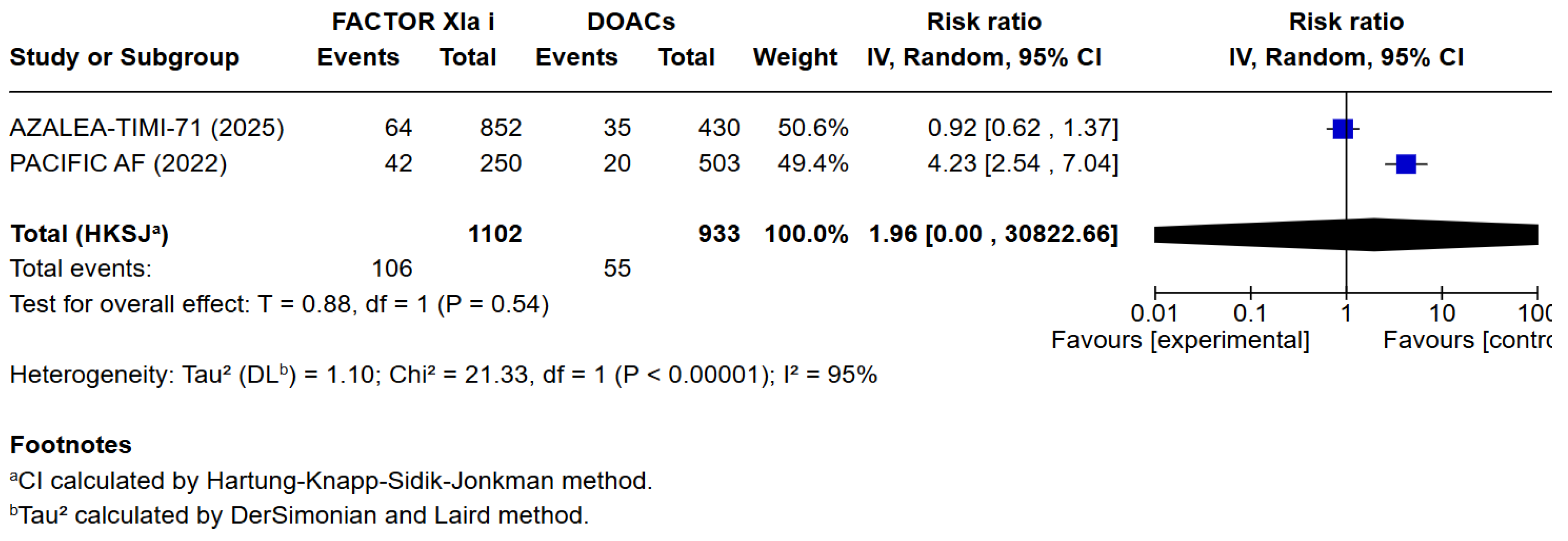

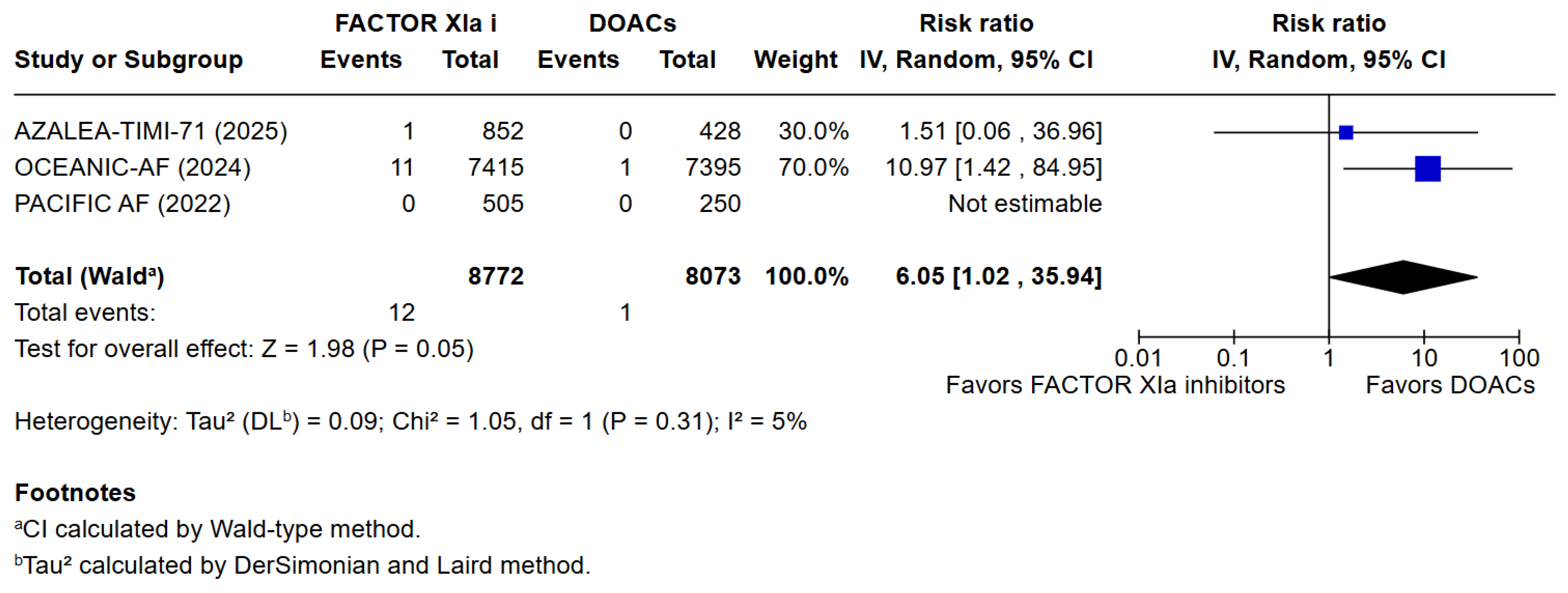

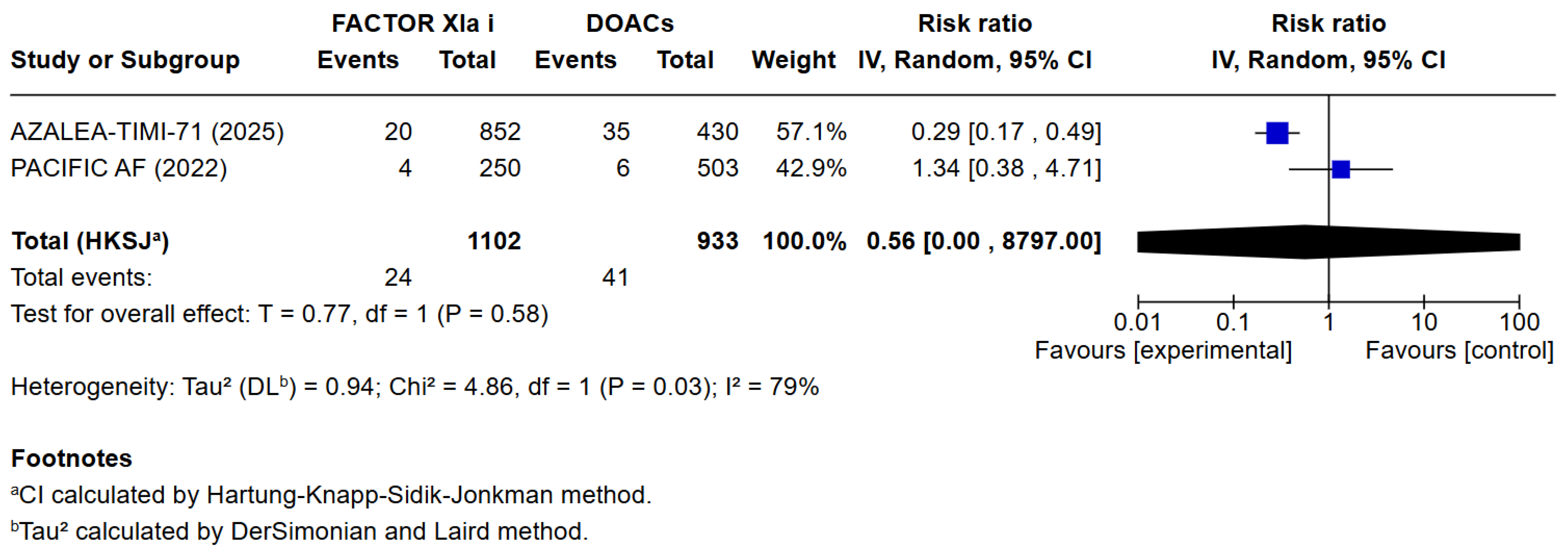

3.3. Quantitative Analysis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AF | Atrial fibrillation |

| OAC | Oral anticoagulation |

| DOAC | Direct oral anticoagulant |

| VKA | Vitamin K antagonist |

| FXI | Factor XI |

| FXIa | activated Factor XI (Factor XIa) |

References

- Linz, D.; Gawalko, M.; Betz, K.; Hendriks, J.M.; Lip, G.Y.; Vinter, N.; Guo, Y.; Johnsen, S. Atrial fibrillation: Epidemiology, screening and digital health. Lancet Reg. Health Eur. 2024, 37, 100786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, V.; Ilkhanoff, L. Anticoagulants for atrial fibrillation: From warfarin and DOACs to the promise of factor XI inhibitors. Front Cardio. Med. 2024, 11, 1352734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joglar, J.A.; Chung, M.K.; Armbruster, A.L.; Benjamin, E.J.; Chyou, J.Y.; Cronin, E.M.; Deswal, A.; Eckhardt, L.L.; Goldberger, Z.D.; Gopinathannair, R.; et al. 2023 ACC/AHA/ACCP/HRS Guideline for the Diagnosis and Management of Atrial Fibrillation: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation 2024, 149, e1–e156, Erratum in Circulation 2024, 149, e167. https://doi.org/10.1161/cir.0000000000001207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greco, A.; Laudani, C.; Spagnolo, M.; Agnello, F.; Faro, D.C.; Finocchiaro, S.; Legnazzi, M.; Mauro, M.S.; Mazzone, P.M.; Occhipinti, G.; et al. Pharmacology and Clinical Development of Factor XI Inhibitors. Circulation 2023, 147, 897–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koulas, I.; Spyropoulos, A.C. A Review of FXIa Inhibition as a Novel Target for Anticoagulation. Hamostaseologie 2023, 43, 28–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruff, C.T.; Patel, S.M.; Giugliano, R.P.; Morrow, D.A.; Hug, B.; Kuder, J.F.; Goodrich, E.L.; Chen, S.-A.; Goodman, S.G.; Joung, B.; et al. Abelacimab versus Rivaroxaban in Patients with Atrial Fibrillation. N. Engl. J. Med. 2025, 392, 361–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piccini, J.P.; Patel, M.R.; Steffel, J.; Ferdinand, K.; Van Gelder, I.C.; Russo, A.M.; Ma, C.-S.; Goodman, S.G.; Oldgren, J.; Hammett, C.; et al. Asundexian versus Apixaban in Patients with Atrial Fibrillation. N. Engl. J. Med. 2025, 392, 23–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piccini, J.P.; Caso, V.; Connolly, S.J.; Fox, K.A.A.; Oldgren, J.; Jones, W.S.; Gorog, D.A.; Viethen, T.; Neumann, C.; Mundl, H.; et al. Safety of the oral factor XIa inhibitor asundexian compared with apixaban in patients with atrial fibrillation (PACIFIC-AF): A multicentre, randomised, double-blind, double-dummy, dose-finding phase 2 study. Lancet 2022, 399, 1383–1390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hsu, C.; Hutt, E.; Bloomfield, D.M.; Gailani, D.; Weitz, J.I. Factor XI Inhibition to Uncouple Thrombosis from Hemostasis: JACC Review Topic of the Week. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2021, 78, 625–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fredenburgh, J.C.; Weitz, J.I. Factor XI as a Target for New Anticoagulants. Hamostaseologie 2021, 41, 104–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salomon, O.; Steinberg, D.M.; Dardik, R.; Rosenberg, N.; Zivelin, A.; Tamarin, I.; Ravid, B.; Berliner, S.; Seligsohn, U. Inherited factor XI deficiency confers no protection against acute myocardial infarction. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2003, 1, 658–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, M.; Molina, C.A.; Toyoda, K.; Bereczki, D.; Bangdiwala, S.I.; Kasner, S.E.; Lutsep, H.L.; Tsivgoulis, G.; Ntaios, G.; Czlonkowska, A.; et al. Safety and efficacy of factor XIa inhibition with milvexian for secondary stroke prevention (AXIOMATIC-SSP): A phase 2, international, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, dose-finding trial. Lancet Neurol. 2024, 23, 46–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verhamme, P.; Yi, B.A.; Segers, A.; Salter, J.; Bloomfield, D.; Büller, H.R.; Raskob, G.E.; Weitz, J.I. ANT-005 TKA Investigators. Abelacimab for Prevention of Venous Thromboembolism. N. Engl. J. Med. 2021, 385, 609–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frost, C.; Song, Y.; Barrett, Y.C.; Wang, J.; Pursley, J.; Boyd, R.A.; LaCreta, F. A randomized direct comparison of the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of apixaban and rivaroxaban. Clin. Pharmacol. Adv. Appl. 2014, 6, 179–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ClinicalTrials.gov. LIBREXIA-AF: Milvexian in Atrial Fibrillation; ClinicalTrials.gov: Bethesda, MD, USA, 2024.

- Campello, E.; Simioni, P.; Prandoni, P.; Ferri, N. Clinical Pharmacology of Factor XI Inhibitors: New Therapeutic Approaches for Prevention of Venous and Arterial Thrombotic Disorders. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 6314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ClinicalTrials.gov. LILAC-TIMI 76: Abelacimab in AF Patients Unsuitable for Anticoagulation; ClinicalTrials.gov: Bethesda, MD, USA, 2024.

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khater, J.; Occhipinti, G.; Cortese, B. Balancing safety and efficacy: Factor XIa inhibitors vs. DOACs in atrial fibrillation: S systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Eur. Heart J. 2025, 46, ehaf784.522. [Google Scholar]

| Author, Year | Design of the Study and Follow-Up Period | Route of Administration of the Drug | Type of OACs | Sample Size (n) | Age (years old) | Female n (%) | CHA2DS2-VASc a Score | Paroxysmal AF b n (%) | Persistent and Longstanding Persistent AF n (%) | Permanent AF n (%) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Factor XIa Inhibitor | DOAC c | Factor XIa Inhibitor | DOAC c | Factor XIa Inhibitor | DOAC c | Factor XIa Inhibitor | DOAC | Factor XIa Inhibitor | DOAC | Factor XIa Inhibitor | DOAC | Factor XIa Inhibitor | DOAC | Factor XIa Inhibitor | DOAC | ||||

| AZALEA TIMI 71 * | Ruff et al., 2025 [6] | RCT | Abelacimab 150 mg SC monthly vs. Abelacimab 90 mg SC monthly vs. Apixaban 20 mg OD | Abelacimab | Rivaroxaban | 427 | 430 | 74 (69–78) Median (IQR d) | 74 (69–79) Median (IQR) | 388 (45.3) | 184 (42.8) | 5 (4–5) Median (IQR) | 5 (4–6) Median (IQR) | 444 (52.2) | 225 (52.6) | 171 (20.1) | 97 (22.7) | 235 (27.6) | 106 (24.8) |

| OCEANIC AF | Piccini et al., 2024 [7] | RCT | Asundexian 50 mg BD vs. Apixaban 5 mg BD oral | Asundexian | Apixaban | 7415 | 7395 | 73.9 ± 7.7 Mean ± SD e | 73.9 ± 7.7 Mean ± SD | 2656 (35.8) | 2558 (34.6) | 4.3 ± 1.3 Mean ± SD | 4.3 ± 1.3 Mean ± SD | 2760 (37.2) | 2641 (35.7) | 2209 (29.8) | 2233 (30.2) | 2327 (31.4) | 2384 (32.2) |

| PACIFIC AF | Piccini et al., 2022 [8] | RCT | Asundexian 50 mg BD vs. Apixaban 5 mg BD oral | Asundexian | Apixaban | 254 | 250 | 73.4 ± 8.2 Mean ± SD | 74.3 ± 8.3 Mean ± SD | 200 (40) | 109 (44) | 3.9 ± 1.3 Mean ± SD | 4.1 ± 1.4 Mean ± SD | 237 (47) | 117 (47) | 147 (29.1) | 65 (26) | - | - |

| Trial Phase | Primary Endpoint | Follow-Up Period | |

|---|---|---|---|

| AZALEA TIMI 71 | - | The primary end point was major or clinically relevant nonmajor bleeding | 22 months |

| OCEANIC AF | Phase 3 | The primary efficacy objective was to determine whether asundexian is at least noninferior to apixaban for the prevention of stroke or systemic embolism. The primary safety objective was to determine whether asundexian is superior to apixaban with respect to major bleeding events. | 12 months |

| PACIFIC AF | Phase 2 | The primary endpoint was the composite of major or clinically relevant non-major bleeding according to International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis criteria, assessed in all patients who took at least one dose of study medication. | 12 weeks |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Khater, J.; Frazzetto, M.; Mahmud, S.H.; Yahyavi, A.; Malakouti, S.; Khialani, B.; Cortese, B. Balancing Safety and Efficacy: Factor XIa INHIBITORS vs. DOACs in Patients with Atrial Fibrillation: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 8234. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14228234

Khater J, Frazzetto M, Mahmud SH, Yahyavi A, Malakouti S, Khialani B, Cortese B. Balancing Safety and Efficacy: Factor XIa INHIBITORS vs. DOACs in Patients with Atrial Fibrillation: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(22):8234. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14228234

Chicago/Turabian StyleKhater, Jacinthe, Marco Frazzetto, Shamin Hayat Mahmud, Ashkan Yahyavi, Sara Malakouti, Bharat Khialani, and Bernardo Cortese. 2025. "Balancing Safety and Efficacy: Factor XIa INHIBITORS vs. DOACs in Patients with Atrial Fibrillation: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 22: 8234. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14228234

APA StyleKhater, J., Frazzetto, M., Mahmud, S. H., Yahyavi, A., Malakouti, S., Khialani, B., & Cortese, B. (2025). Balancing Safety and Efficacy: Factor XIa INHIBITORS vs. DOACs in Patients with Atrial Fibrillation: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(22), 8234. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14228234