Infective Endocarditis and Excessive Use of B− Blood Type Due to Surgical Treatment—Is It Only a Local Problem? LODZ-ENDO Results (2015–2025)

Abstract

1. Background

2. Aim

3. Methods

Statically Analysis

4. Results

5. Discussion

6. Limitations

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Delgado, V.; Ajmone Marsan, N.; de Waha, S.; Bonaros, N.; Brida, M.; Burri, H.; Caselli, S.; Doenst, T.; Ederhy, S.; Erba, P.A.; et al. 2023 ESC Guidelines for the management of endocarditis: Developed by the task force on the management of endocarditis of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) Endorsed by the European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS) and the European Association of Nuclear Medicine (EANM). Eur. Heart J. 2023, 44, 3948–4042. [Google Scholar]

- Orzech, J.W.; Zatorska, K.; Grabowski, M.; Miłkowska, M.; Jaworska-Wilczyńska, M.; Kowalik, I.; Kukulski, T.; Lesiak, M.; Surdacki, A.; Hryniewiecki, T. Preliminary results from the Polish Infective Endocarditis Registry (POL-ENDO): Time to change clinical practice? Pol. Heart J. 2024, 82, 609–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habib, G.; Erba, P.A.; Iung, B.; Donal, E.; Cosyns, B.; Laroche, C.; Popescu, B.A.; Prendergast, B.; Tornos, P.; Sadeghpour, A.; et al. Clinical presentation, aetiology and outcome of infective endocarditis. Results of the ESC-EORP EURO-ENDO (European infective endocarditis) registry: A prospective cohort study. Eur. Heart J. 2019, 40, 3222–3232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooling, L. Blood Groups in Infection and Host Susceptibility. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2015, 28, 801–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Check, J.H.; O’Neill, E.A.; O’Neill, K.E.; Fuscaldo, K.E. Effect of anti-B antiserum on the phagocytosis of Escherichia coli. Infect. Immun. 1972, 6, 95–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, M.G.; Tolchin, D.; Halpern, C. Enteric bacterial agents and the ABO blood groups. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 1971, 23, 135–145. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Available online: https://www.gov.pl/web/nck (accessed on 14 October 2025).

- Available online: https://krwiodawcy.org/ (accessed on 14 October 2025).

- Available online: https://stat.gov.pl/obszary-tematyczne/zdrowie/zdrowie/krwiodawstwo-w-2024-r-,18,4.html (accessed on 14 October 2025).

- Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/blood-safety-and-availability (accessed on 14 October 2025).

- Haldane, J.B. The blood-group frequencies of European peoples, and racial origins. Hum. Biol. 1989, 61, 667–690; discussion 691–702. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Mäkivuokko, H.; Lahtinen, S.J.; Wacklin, P.; Tuovinen, E.; Tenkanen, H.; Nikkilä, J.; Björklund, M.; Aranko, K.; Ouwehand, A.C.; Mättö, J. Association between the ABO blood group and the human intestinal microbiota composition. BMC Microbiol. 2012, 12, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sugrue, J.A.; Smith, M.; Posseme, C.; Charbit, B.; Milieu Interieur Consortium; Bourke, N.M.; Duffy, D.; O’Farrelly, C. Rhesus negative males have an enhanced IFNγ-mediated immune response to influenza A virus. Genes Immun. 2022, 23, 93–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rana, R.; Ranjan, V.; Kumar, N. Association of ABO and Rh Blood Group in Susceptibility, Severity, and Mortality of Coronavirus Disease 2019: A Hospital-Based Study From Delhi, India. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2021, 11, 767771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, E.A.; Parikh, R.; Grandi, S.M.; Ray, J.G.; Cohen, E. ABO and Rh blood groups and risk of infection: Systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Infect. Dis. 2023, 23, 797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jajosky, R.P.; O’Bryan, J.; Spichler-Moffarah, A.; Jajosky, P.G.; Krause, P.J.; Tonnetti, L. The impact of ABO and RhD blood types on Babesia microti infection. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2023, 17, e0011060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rattanapan, Y.; Duangchan, T.; Wangdi, K.; Mahittikorn, A.; Kotepui, M. Association between Rhesus Blood Groups and Malaria Infection: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Trop. Med. Infect. Dis. 2023, 8, 190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jericó, C.; Zalba-Marcos, S.; Quintana-Díaz, M.; López-Villar, O.; Santolalla-Arnedo, I.; Abad-Motos, A.; Laso-Morales, M.J.; Sancho, E.; Subirà, M.; Bassas, E.; et al. Relationship between ABO Blood Group Distribution and COVID-19 Infection in Patients Admitted to the ICU: A Multicenter Observational Spanish Study. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 3042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atefi, A.; Binesh, F.; Ayatollahi, J.; Atefi, A.; Dehghan Mongabadi, F. Determination of Relative Frequency of ABO/Rh Blood Groups in Patients with Bacteremia in Shahid Sadoughi Hospital, Yazd, Iran. Zahedan J. Res. Med. Sci. 2016, 18, e3500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liufu, R.; Chen, Y.; Wang, J.Y.; Wang, Y.Y.; Wu, Y.; Jiang, W.; Wang, C.Y.; Peng, J.M.; Weng, L.; Du, B. ABO Blood Group and Risk Associated With Sepsis-Associated Thrombocytopenia: A Single-Center Retrospective Study. Crit. Care Med. 2025, 53, e353–e361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamil, S.S.; Khaudhair, A.T.; Hamid, H.T. Associa:on of Dental Caries with Different ABO Blood Groups. Dentstry 2024, 3000, a001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazumdar, P.; Das, U.K.; Goswami, S. Correlation between blood group and dental caries in 20–60 years age group: A study. Int. J. Adv. Res. 2014, 2, 413–424. [Google Scholar]

- Gautam, A.; Mittal, N.; Singh, T.B.; Srivastava, R.; Verma, P.K. Correlation of ABO Blood Group Phenotype and Rhesus Factor with Periodontal Disease: An Observational Study. Contemp. Clin. Dent. 2017, 8, 253–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, L.; Xu, J.; Chai, Y.; Wu, W. Global, regional, and national burden of infective endocarditis from 2010 to 2021 and predictions for the next five years: Results from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. BMC Public Health 2025, 25, 1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morawiec, R.; Misiewicz, A.; Bollin, P.; Kośny, M.; Krejca, M.; Drożdż, J. The importance of etiologic factor identification in patients with infective endocarditis—Results of tertiary center analysis (2015–2023). Cardiol. J. 2024, 31, 922–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Blood Type | Frequency |

|---|---|

| A+ | 32% |

| A− | 6% |

| B+ | 15% |

| B− | 2% |

| AB+ | 7% |

| AB− | 1% |

| 0+ | 31% |

| 0− | 6% |

| Overall (n = 333) | ||||||||

| Women [n, (%)] | 254 (77.2%) | |||||||

| Men [n, (%)] | 75 (22.8%) | |||||||

| Age [Me, (IQR)] | 61 (47–68) | |||||||

| Left ventricle ejection fraction (%) [Me, (IQR)] | 55 (48–60) | |||||||

| Treatment—cardiac surgery [n, (%)] | 227 (68.2%) | |||||||

| In-hospital mortality | 99 (30.1%) | |||||||

| Diabetes mellitus | 83 (24.9%) | |||||||

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 22 (6.6%) | |||||||

| Left-sided IE | 305 (91.6%) | |||||||

| Right-sided IE | 20 (6%) | |||||||

| Both-sided IE | 8 (2.4%) | |||||||

| Staphylococcus spp. | 81 (24.3%) | |||||||

| Enterococcus spp. | 38 (11.4%) | |||||||

| Streptococcus spp. | 28 (8.4%) | |||||||

| Other | 21 (6.3%) | |||||||

| Unidentified | 165 (49.5%) | |||||||

| WBC (×106/L) [Me, (IQR)] | 9.3 (7.13–11.9) | |||||||

| Lym (×106/L) [Me, (IQR)] | 1.41 (1.04–1.91) | |||||||

| Neu (×106/L) [Me, (IQR)] | 6.83 (4.76–9.18) | |||||||

| Plt (×106/L) [Me, (IQR)] | 239 (170–303) | |||||||

| Hgb (g/dL) [Me, (IQR)] | 10.5 (9.4–11.8) | |||||||

| CRP (mg/L) [Me, (IQR)] | 48.05 (22–101.9) | |||||||

| NT-proBNP (pg/mL) [Me, (IQR)] | 4859 (1785–18,575.5) | |||||||

| eGFR (ml/min/1.73 m2) [Me, (IQR)] | 66.6 (40.1–91.8) | |||||||

| Blood types AB0/Rh [n, (%)] (n = 329) | ||||||||

| A+ | 103 (31.3%) | |||||||

| A− | 16 (4.9%) | |||||||

| B+ | 52 (15.8%) | |||||||

| B− | 17 (5.2%) | |||||||

| AB+ | 18 (5.5%) | |||||||

| AB− | 4 (1.2%) | |||||||

| 0+ | 100 (30.4%) | |||||||

| 0− | 19 (5.8%) | |||||||

| Blood types AB0/Rh (by sex) [n, (%)] (n = 329) | ||||||||

| Men | Women | |||||||

| A+ | 80 (31.5%) | 23 (30.7%) | p = 0.36 | |||||

| A− | 10 (3.9%) | 6 (8%) | ||||||

| B+ | 42 (16.5%) | 10 (13.3%) | ||||||

| B− | 10 (3.9%) | 7 (9.3%) | ||||||

| AB+ | 15 (5.9%) | 3 (4%) | ||||||

| AB− | 3 (1.2%) | 1 (1.3%) | ||||||

| 0+ | 81 (31.9%) | 19 (25.3%) | ||||||

| 0− | 13 (5.1%) | 6 (8%) | ||||||

| Blood types AB0/Rh (age—median) (n = 329) | ||||||||

| A+ | 61 | p = 0.21 | ||||||

| A− | 61 | |||||||

| B+ | 55 | |||||||

| B− | 65 | |||||||

| AB+ | 65 | |||||||

| AB− | 62.5 | |||||||

| 0+ | 58 | |||||||

| 0− | 63 | |||||||

| Blood types AB0/Rh—in-hospital mortality [n, (%)] (n = 329) | ||||||||

| A+ | 33 (33.3%) | p = 0.67 | ||||||

| A− | 2 (2.0%) | |||||||

| B+ | 18 (18.2%) | |||||||

| B− | 5 (5.1%) | |||||||

| AB+ | 4 (4.0%) | |||||||

| AB− | 2 (2.0%) | |||||||

| 0+ | 28 (28.3%) | |||||||

| 0− | 7 (7.1%) | |||||||

| Time admission to surgery (days) [Me, (IQR)] (n = 227) | ||||||||

| A+ | 11 (7–21) | p = 0.82 | ||||||

| A− | 9 (6.5–13) | |||||||

| B+ | 13 (8–16) | |||||||

| B− | 13 (8.5–17.5) | |||||||

| AB+ | 12.5 (7–14) | |||||||

| AB− |

| |||||||

| 0+ | 11 (6–16) | |||||||

| 0− | 15 (7–20) | |||||||

| Blood types AB0/Rh by etiologic factor [n, (%)] (n = 329; % within each blood type] p = NS | ||||||||

| A+ | A− | B+ | B− | AB+ | AB− | 0+ | 0− | |

| Staphylococcus spp. | 24 (23.3%) | 1 (6.3%) | 11 (21.2%) | 6 (35.3%) | 8 (44.4%) | 4 (100%) | 21 (21.0%) | 5 (26.3%) |

| Enterococcus spp. | 11 (10.7%) | 1 (6.3%) | 8 15.4%) | 2 (11.8%) | 3 (16.7%) | 0 | 10 (10.0%) | 3 (15.8%) |

| Streptococcus spp. | 8 (7.8%) | 2 (12.5%) | 7 (13.5%) | 0 | 1 (5.6%) | 0 | 10 (10.0%) | 0 |

| Other | 10 (9.7%) | 1 (6.3%) | 2 (3.8%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 (4.0%) | 4 (21.1%) |

| Unidentified | 50 (48.5%) | 11 (68.8%) | 24 (46.2%) | 9 (52.9%) | 6 (33.3%) | 0 | 55 (55.0%) | 7 (36.8%) |

| Blood Type (AB0/Rh) | Number Observed | Number Expected | % Observed | % Expected | OR | 95% CI OR | p (Fisher) | p (χ2) | Test Power |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A+ | 105 | 105.3 | 31.9 | 32 | 1.0 | [0.72–1.39] | 0.93 | 0.96 | 0.06 |

| A− | 16 | 19.7 | 4.9 | 6 | 0.81 | [0.43–1.52] | 0.6 | 0.69 | 0.3 |

| B+ | 52 | 49.4 | 15.8 | 15 | 1.06 | [0.71–1.58] | 0.81 | 0.82 | 0.05 |

| B− | 17 | 6.6 | 5.2 | 2 | 2.88 | [1.17–7.29] | 0.029/0.232 * | 0.031/0.248 * | 0.89 |

| AB+ | 18 | 23 | 5.5 | 7 | 0.77 | [0.42–1.41] | 0.41 | 0.49 | 0.17 |

| AB− | 4 | 3.3 | 1.2 | 1 | 1.21 | [0.33–4.40] | 0.73 | 0.75 | 0.05 |

| 0+ | 98 | 102 | 29.8 | 31 | 0.96 | [0.69–1.34] | 0.81 | 0.83 | 0.07 |

| 0− | 19 | 19.7 | 5.8 | 6 | 0.97 | [0.54–1.75] | 1 | 1 | 0.05 |

| Rh+ (total) | 252 | 279 | 83.0 | 85.0 | 0.83 | [0.53–1.28] | 0.49 | 0.48 | 0.19 |

| Rh− (total) | 52 | 50 | 17.0 | 15.0 | 1.17 | [0.76–1.80] | 0.49 | 0.48 | 0.19 |

| A (total) | 114 | 125 | 34.7 | 38.0 | 0.86 | [0.65–1.13] | 0.30 | 0.27 | 0.25 |

| B (total) | 62 | 56 | 18.9 | 17.0 | 1.13 | [0.80–1.60] | 0.51 | 0.48 | 0.23 |

| AB (total) | 20 | 26 | 6.1 | 8.0 | 0.74 | [0.44–1.24] | 0.29 | 0.27 | 0.27 |

| O (total) | 109 | 111 | 33.1 | 33.0 | 1.00 | [0.75–1.33] | 0.99 | 0.98 | 0.05 |

| Overall AB0/Rh | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 0.03 ** | - |

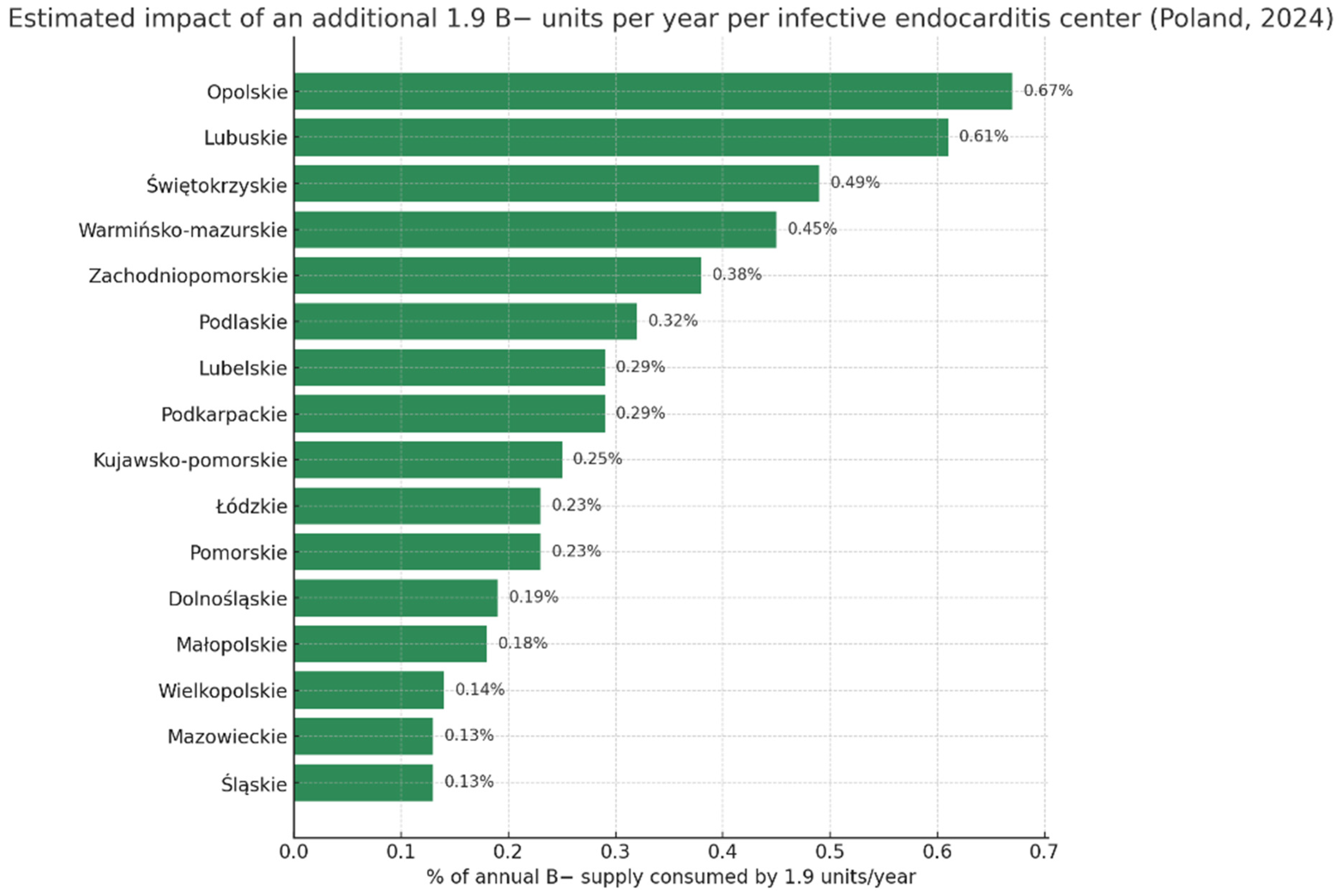

| Region | Population | Donors Per 10,000 [9] | Annual Donations | Estimated B− Supply (2%) | % of B− Supply Consumed by 1.9 Units/Site/Year |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| POLAND (total) | 38,290,000 | 172.5 | 617,000 | 12,340 | 0.015% |

| Dolnośląskie | 2,875,000 | 171.1 | 49,200 | 984 | 0.193% |

| Kujawsko-Pomorskie | 1,991,000 | 193.3 | 38,500 | 770 | 0.247% |

| Lubelskie | 2,005,000 | 163.6 | 32,800 | 656 | 0.290% |

| Lubuskie | 975,000 | 160.0 | 15,600 | 312 | 0.609% |

| Łódzkie | 2,355,000 | 172.8 | 40,700 | 814 | 0.233% |

| Małopolskie | 3,427,000 | 154.9 | 53,100 | 1062 | 0.179% |

| Mazowieckie | 5,512,000 | 132.4 | 73,000 | 1460 | 0.130% |

| Opolskie | 933,000 | 152.2 | 14,200 | 284 | 0.669% |

| Podkarpackie | 2,066,000 | 157.8 | 32,600 | 652 | 0.291% |

| Podlaskie | 1,134,000 | 262.8 | 29,800 | 596 | 0.319% |

| Pomorskie | 2,361,000 | 173.7 | 41,000 | 820 | 0.232% |

| Śląskie | 4,304,000 | 166.1 | 71,500 | 1430 | 0.133% |

| Świętokrzyskie | 1,164,000 | 167.6 | 19,500 | 390 | 0.487% |

| Warmińsko-Mazurskie | 1,352,000 | 157.5 | 21,300 | 426 | 0.446% |

| Wielkopolskie | 3,484,000 | 200.4 | 69,800 | 1396 | 0.136% |

| Zachodniopomorskie | 1,627,000 | 153.7 | 25,000 | 500 | 0.380% |

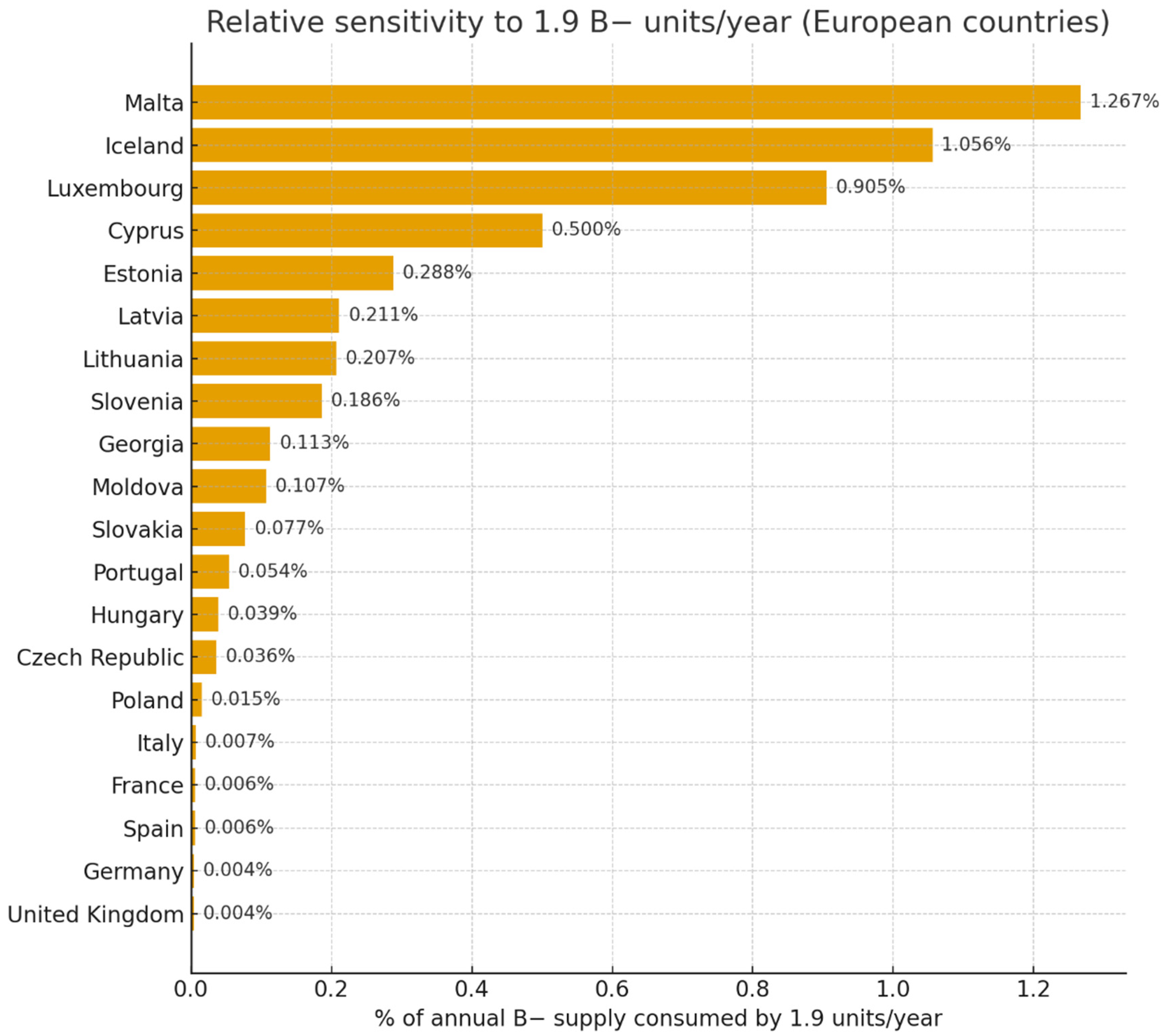

| Country | Population (Million) | World Bank Income | Donations/1000 | Annual Donations | B− (%) | Annual B− Supply | % of B− Supply Consumed by 1.9 Units/Site/Year |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Poland | 38.3 | Upper-middle | 16.4 | 624,000 | 2.0 | 12,480 | 0.015% |

| Germany | 84.1 | High | 31.5 | 2,647,000 | 2.0 | 52,940 | 0.004% |

| France | 68.4 | High | 31.5 | 2,155,000 | 1.4 | 30,170 | 0.006% |

| Spain | 47.3 | High | 31.5 | 1,490,000 | 2.0 | 29,800 | 0.006% |

| Italy | 61.0 | High | 31.5 | 1,922,000 | 1.5 | 28,830 | 0.007% |

| United Kingdom | 68.5 | High | 31.5 | 2,159,000 | 2.0 | 43,180 | 0.004% |

| Portugal | 10.2 | High | 31.5 | 321,000 | 1.1 | 3530 | 0.054% |

| Czech Republic | 10.8 | Upper-middle | 16.4 | 177,000 | 3.0 | 5310 | 0.036% |

| Hungary | 9.9 | Upper-middle | 16.4 | 162,000 | 3.0 | 4860 | 0.039% |

| Slovakia | 5.6 | Upper-middle | 16.4 | 92,000 | 2.7 | 2480 | 0.077% |

| Slovenia | 2.1 | Upper-middle | 16.4 | 34,000 | 3.0 | 1020 | 0.186% |

| Estonia | 1.34 | Upper-middle | 16.4 | 22,000 | 3.0 | 660 | 0.288% |

| Latvia | 1.85 | Upper-middle | 16.4 | 30,000 | 3.0 | 900 | 0.211% |

| Lithuania | 2.8 | Upper-middle | 16.4 | 46,000 | 2.0 | 920 | 0.207% |

| Iceland | 0.36 | High | 31.5 | 11,000 | 1.6 | 180 | 1.056% |

| Malta | 0.47 | High | 31.5 | 15 000 | 1.0 | 150 | 1.267% |

| Luxembourg | 0.67 | High | 31.5 | 21,000 | 1.0 | 210 | 0.905% |

| Cyprus | 1.32 | High | 31.5 | 42,000 | 0.9 | 380 | 0.500% |

| Moldova | 3.6 | Upper-middle | 16.4 | 59,000 | 3.0 | 1770 | 0.107% |

| Georgia | 4.9 | Upper-middle | 16.4 | 80,000 | 2.1 | 1680 | 0.113% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Morawiec, R.; Mlynczyk, K.; Krejca, M.; Drozdz, J. Infective Endocarditis and Excessive Use of B− Blood Type Due to Surgical Treatment—Is It Only a Local Problem? LODZ-ENDO Results (2015–2025). J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 8101. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14228101

Morawiec R, Mlynczyk K, Krejca M, Drozdz J. Infective Endocarditis and Excessive Use of B− Blood Type Due to Surgical Treatment—Is It Only a Local Problem? LODZ-ENDO Results (2015–2025). Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(22):8101. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14228101

Chicago/Turabian StyleMorawiec, Robert, Karolina Mlynczyk, Michal Krejca, and Jaroslaw Drozdz. 2025. "Infective Endocarditis and Excessive Use of B− Blood Type Due to Surgical Treatment—Is It Only a Local Problem? LODZ-ENDO Results (2015–2025)" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 22: 8101. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14228101

APA StyleMorawiec, R., Mlynczyk, K., Krejca, M., & Drozdz, J. (2025). Infective Endocarditis and Excessive Use of B− Blood Type Due to Surgical Treatment—Is It Only a Local Problem? LODZ-ENDO Results (2015–2025). Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(22), 8101. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14228101