Redo-Transcatheter Aortic Valve Implantation (Redo-TAVI)—Pilot Study from Multicentre Nationwide Registry

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Baseline Characteristics Before Redo-Procedures and Index TAVI Details

3.2. Redo-TAVI Procedural Characteristics and 1-Year Outcomes

3.3. Multivariable Cox Proportional Hazard for the Primary Endpoint

4. Discussion

5. Limitations

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Vahanian, A.; Beyersdorf, F.; Praz, F.; Milojevic, M.; Baldus, S.; Bauersachs, J.; Capodanno, D.; Conradi, L.; De Bonis, M.; De Paulis, R.; et al. 2021 ESC/EACTS Guidelines for the management of valvular heart disease: Developed by the Task Force for the management of valvular heart disease of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and the European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS). Eur. Heart J. 2021, 43, 561–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meier, D.; Tzimas, G.; Akodad, M.; Fournier, S.; Leipsic, J.A.; Blanke, P.; Wood, D.A.; Sellers, S.L.; Webb, J.G.; Sathananthan, J. TAVR in TAVR: Where Are We in 2023 for Management of Failed TAVR Valves? Curr. Cardiol. Rep. 2023, 25, 1425–1431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Landes, U.; Webb, J.G.; De Backer, O.; Sondergaard, L.; Abdel-Wahab, M.; Crusius, L.; Kim, W.K.; Hamm, C.; Buzzatti, N.; Montorfano, M.; et al. Repeat Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacement for Transcatheter Prosthesis Dysfunction. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2020, 75, 1882–1893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huczek, Z.; Jędrzejczyk, S.; Jagielak, D.; Dąbrowski, M.; Grygier, M.; Gruz-Kwapisz, M.; Fil, W.; Olszówka, P.; Frank, M.; Wilczek, K.; et al. Transcatheter aortic valve-in-valve implantation for failed surgical bioprostheses: Results from the Polish Transcatheter Aortic Valve-in-Valve Implantation (ViV-TAVI) Registry. Pol. Arch. Intern. Med. 2022, 132, 16149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galhardo, A.; Avvedimento, M.; Mengi, S.; Rodés-Cabau, J. Redo-TAVR: Essential Concepts, Updated Data and Current Gaps in Evidence. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 4788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Généreux, P.; Leon, M.B.; Dar, R.D.; Puri, R.; Rozenman, Y.; Szerlip, M.; Yadav, P.K.; Thourani, V.H.; Pibarot, P.; Dvir, D. Predicting Treatment of Bioprosthetic Aortic Valve Failure in the United States: A Proposed Model. Struct. Heart 2024, 9, 100339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinsson, A.; Nielsen, S.J.; Milojevic, M.; Redfors, B.; Omerovic, E.; Tønnessen, T.; Gudbjartsson, T.; Dellgren, G.; Jeppsson, A. Life Expectancy After Surgical Aortic Valve Replacement. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2021, 78, 2147–2157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landes, U.; Richter, I.; Danenberg, H.; Kornowski, R.; Sathananthan, J.; De Backer, O.; Søndergaard, L.; Abdel-Wahab, M.; Yoon, S.H.; Makkar, R.R.; et al. Outcomes of Redo Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacement According to the Initial and Subsequent Valve Type. JACC Cardiovasc. Interv. 2022, 15, 1543–1554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vincent, F.; Ternacle, J.; Denimal, T.; Shen, M.; Redfors, B.; Delhaye, C.; Simonato, M.; Debry, N.; Verdier, B.; Shahim, B.; et al. Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacement in Bicuspid Aortic Valve Stenosis. Circulation 2021, 143, 1043–1061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elbadawi, A.; Saad, M.; Elgendy, I.Y.; Barssoum, K.; Omer, M.A.; Soliman, A.; Almahmoud, M.F.; Ogunbayo, G.O.; Mentias, A.; Gilani, S.; et al. Temporal Trends and Outcomes of Transcatheter Versus Surgical Aortic Valve Replacement for Bicuspid Aortic Valve Stenosis. JACC Cardiovasc. Interv. 2019, 12, 1811–1822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fiorina, C.; Massussi, M.; Ancona, M.; Montorfano, M.; Petronio, A.S.; Tarantini, G.; Castriota, F.; Chizzola, G.; Costa, G.; Tamburino, C.; et al. Mid-term outcomes and hemodynamic performance of transcatheter aortic valve implantation in bicuspid aortic valve stenosis: Insights from the bicuSpid TAvi duraBILITY (STABILITY) registry. Catheter. Cardiovasc. Interv. 2023, 102, 1132–1139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, S.H.; Kim, W.K.; Dhoble, A.; Milhorini Pio, S.; Babaliaros, V.; Jilaihawi, H.; Pilgrim, T.; De Backer, O.; Bleiziffer, S.; Vincent, F.; et al. Bicuspid Aortic Valve Morphology and Outcomes After Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacement. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2020, 76, 1018–1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gunning, P.S.; Saikrishnan, N.; McNamara, L.M.; Yoganathan, A.P. An in vitro evaluation of the impact of eccentric deployment on transcatheter aortic valve hemodynamics. Ann. Biomed. Eng. 2014, 42, 1195–1206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatoum, H.; Dollery, J.; Lilly, S.M.; Crestanello, J.A.; Dasi, L.P. Sinus Hemodynamics Variation with Tilted Transcatheter Aortic Valve Deployments. Ann. Biomed. Eng. 2019, 47, 75–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xuan, Y.; Dvir, D.; Wang, Z.; Ye, J.; Guccione, J.; Ge, L.; Tseng, E. Stent and leaflet stresses across generations of balloon-expandable transcatheter aortic valves. Interact. Cardiovasc. Thorac. Surg. 2020, 30, 879–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huczek, Z.; Protasiewicz, M.; Dąbrowski, M.; Parma, R.; Hudziak, D.; Olszówka, P.; Targoński, R.; Grodecki, K.; Frank, M.; Scisło, P.; et al. Transcatheter aortic valve implantation for failed surgical and transcatheter prostheses. Expert opinion of the Association of Percutaneous Cardiovascular Interventions of the Polish Cardiac Society. Kardiol. Pol. 2023, 81, 646–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, G.H.L.; Amat-Santos, I.J.; De Backer, O.; Avvedimento, M.; Redondo, A.; Barbanti, M.; Costa, G.; Tchétché, D.; Eltchaninoff, H.; Kim, W.K.; et al. Rationale, Definitions, Techniques, and Outcomes of Commissural Alignment in TAVR: From the ALIGN-TAVR Consortium. JACC Cardiovasc. Interv. 2022, 15, 1497–1518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dvir, D.; Leon, M.B.; Abdel-Wahab, M.; Unbehaun, A.; Kodali, S.; Tchetche, D.; Pibarot, P.; Leipsic, J.; Blanke, P.; Gerckens, U.; et al. First-in-Human Dedicated Leaflet Splitting Device for Prevention of Coronary Obstruction in Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacement. JACC Cardiovasc. Interv. 2023, 16, 94–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmidt, T.; Frerker, C.; Alessandrini, H.; Schlüter, M.; Kreidel, F.; Schäfer, U.; Thielsen, T.; Kuck, K.-H.; Jose, J.; Holy, E.W.; et al. Redo TAVI: Initial experience at two German centres. EuroIntervention 2016, 12, 875–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barbanti, M.; Webb, J.G.; Tamburino, C.; Van Mieghem, N.M.; Makkar, R.R.; Piazza, N.; Latib, A.; Sinning, J.-M.; Won-Keun, K.; Bleiziffer, S.; et al. Outcomes of Redo Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacement for the Treatment of Postprocedural and Late Occurrence of Paravalvular Regurgitation and Transcatheter Valve Failure. Circ. Cardiovasc. Interv. 2016, 9, e003930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Percy, E.D.; Harloff, M.T.; Hirji, S.; McGurk, S.; Yazdchi, F.; Newell, P.; Malarczyk, A.; Sabe, A.; Landes, U.; Webb, J.; et al. Nationally Representative Repeat Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacement Outcomes: Report From the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. JACC Cardiovasc. Interv. 2021, 14, 1717–1726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Testa, L.; Agnifili, M.; Van Mieghem, N.M.; Tchétché, D.; Asgar, A.W.; De Backer, O.; Latib, A.; Reimers, B.; Stefanini, G.; Trani, C.; et al. Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacement for Degenerated Transcatheter Aortic Valves: The TRANSIT International Project. Circ. Cardiovasc. Interv. 2021, 14, e010440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Makkar, R.R.; Kapadia, S.; Chakravarty, T.; Cubeddu, R.J.; Kaneko, T.; Mahoney, P.; Patel, D.; Gupta, A.; Cheng, W.; Kodali, S.; et al. Outcomes of repeat transcatheter aortic valve replacement with balloon-expandable valves: A registry study. Lancet 2023, 402, 1529–1540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eggebrecht, H.; Schmermund, A.; Voigtländer, T.; Kahlert, P.; Erbel, R.; Mehta, R.H. Risk of stroke after transcatheter aortic valve implantation (TAVI): A meta-analysis of 10,037 published patients. EuroIntervention 2012, 8, 129–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mangieri, A.; Montalto, C.; Poletti, E.; Sticchi, A.; Crimi, G.; Giannini, F.; Latib, A.; Capodanno, D.; Colombo, A. Thrombotic Versus Bleeding Risk After Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacement: JACC Review Topic of the Week. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2019, 74, 2088–2101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dangas, G.D.; Tijssen, J.G.P.; Wöhrle, J.; Søndergaard, L.; Gilard, M.; Möllmann, H.; Makkar, R.R.; Herrmann, H.C.; Giustino, G.; Baldus, S.; et al. A Controlled Trial of Rivaroxaban after Transcatheter Aortic-Valve Replacement. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 382, 120–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Age, years | 75 ± 13 |

| Male | 20 (62.5) |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 28.6 ± 4.7 |

| Body surface area, m2 | 1.90 ± 0.23 |

| Society of Thoracic Surgeons score | 6.5 ± 2.8 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 12 (37.5) |

| Hypertension | 30 (93.8) |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 6 (18.8) |

| Atrial fibrillation | 14 (43.8) |

| Oral anticoagulation | 13 (40.6) |

| Prior myocardial infarction | 10 (31.3) |

| Prior stroke or transient ischemic attack | 7 (21.9) |

| Prior coronary artery bypass grafting | 8 (25.0) |

| Prior percutaneous coronary intervention | 16 (50.0) |

| New York Heart Association class III–IV | 22 (68.8) |

| Permanent pacemaker | 7 (21.9) |

| Chronic kidney disease | 19 (59.4) |

| Hemodialysis | 1 (3.1) |

| Glomerular filtration rate, mL/min/1.73 m2 | 53 ± 27 |

| Hemoglobin, g/dL | 11.6 ± 1.7 |

| Bicuspid anatomy (CT-based) | 12 (37.5) |

| Type 1 (Sievers classification) | 11 (91.7) |

| Transfemoral access | 29 (90.6) |

| Predilatation | 19 (59.3) |

| Postdilatation | 9 (28.1) |

| Prosthesis type | |

| Self-expanding | 27 (84.4) |

| Corevalve/Evolut R/Pro | 19 |

| Accurate Neo/Neo 2 | 5 |

| Portico | 2 |

| Hydra | 1 |

| Balloon-expanding (Sapien XT/3) | 4 (12.5) |

| Other (Lotus) | 1 (3.1) |

| Mean prosthesis size, mm | 27.7 ± 3 |

| Discharge | |

| Perivalvular leak moderate/severe (echo) | 6 (18.7) |

| Mean residual pressure gradient (echo), mmHg | 12.7 (7) |

| Dual antiplatelet therapy | 20 (62.5) |

| Oral anticoagulation | 10 (31.3) |

| Single antiplatelet therapy | 2 (6.2) |

| Left ventricular ejection fraction, % | 52 ± 13 |

| Aortic valve area, cm2 | 1.17 ± 0.59 |

| Aortic valve area indexed, cm2/m2 | 0.53 ± 0.17 |

| Aortic velocity, m/s | 3.5 ± 1.1 |

| Pressure gradient mean, mmHg | 24 ± 21 |

| Pressure gradient max, mmHg | 42 ± 35 |

| Stenosis | 10 (31.3) |

| Regurgitation | 19 (59.4) |

| Mixed | 3 (9.4) |

| History of index THV endocarditis | 4 (12.5) |

| History of index THV thrombosis | 1 (3.1) |

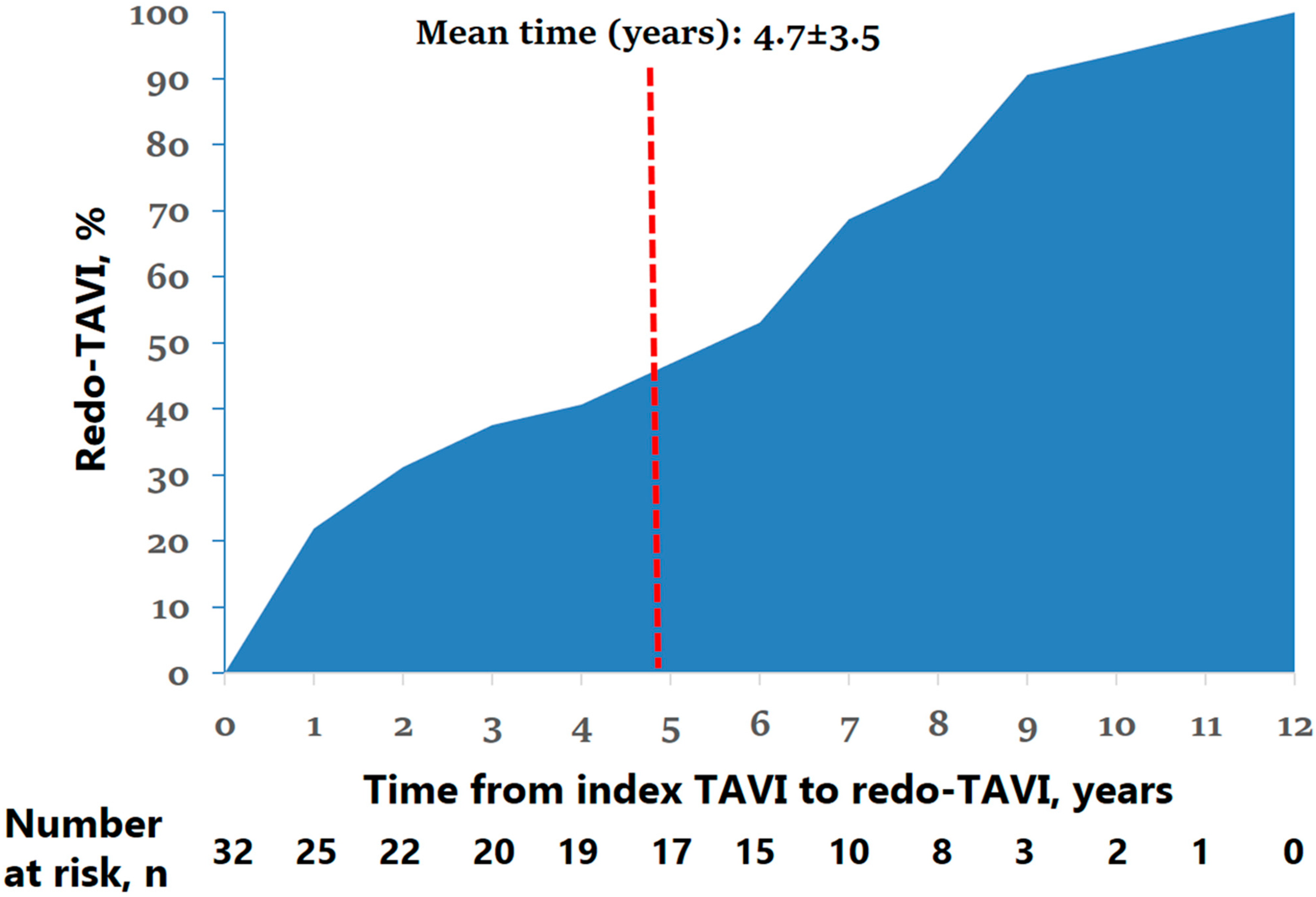

| Mean time from index TAVI, years | 4.7 ± 3.5 |

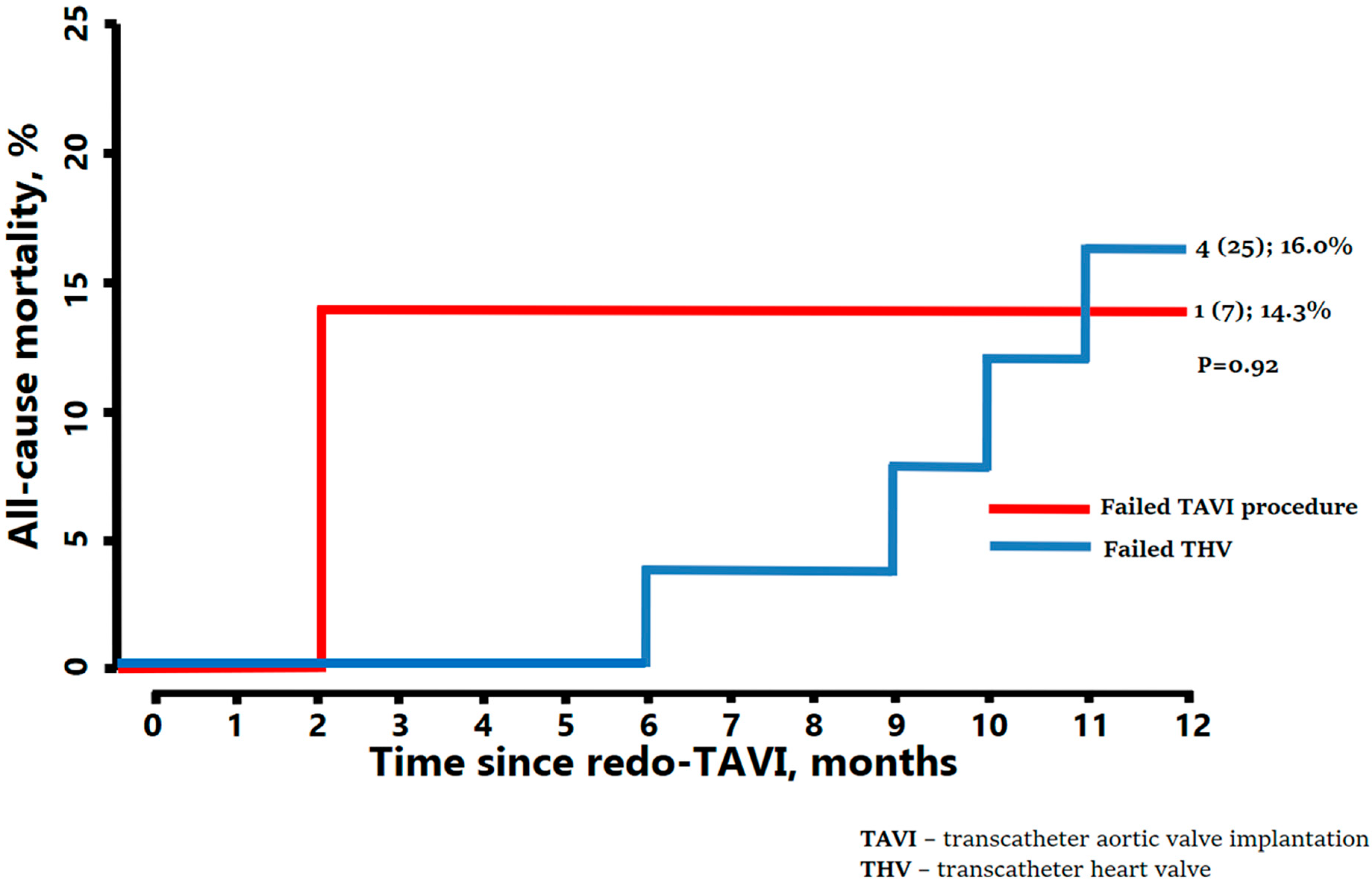

| Procedural failure * (up to 1 year) | 7 (21.9) |

| Bicuspid as native anatomy | 3 (42.8) |

| Transcatheter heart valve failure ** (beyond 1 year) | 25 (78.1) |

| Bicuspid as native anatomy | 9 (36) |

| Transfemoral access | 32 (100) |

| Prosthesis type | |

| Balloon-expanding | 24 (75) |

| Sapien 3/Ultra | 23 |

| Myval | 1 |

| Self-expanding | 8 (25) |

| Evolut R/Pro | 7 |

| Portico | 1 |

| Mean prosthesis size, mm | 25.7 ± 3 |

| Balloon-expandable in self-expandable | 22 (68.7) |

| Self-expandable in balloon-expandable | 6 (18.7) |

| Self-expandable in self-expandable | 3 (9.4) |

| Balloon-expandable in balloon-expandable | 1 (3.1) |

| Predilatation | 7 (21.8) |

| Postdilatation | 11 (34.4) |

| Coronary protection | 4 (12.5) |

| Chimney stenting | 2 (50) |

| Leaflet laceration (BASILICA) | 2 (50) |

| Discharge | |

| Perivalvular leak moderate/severe (echo) | 3 (9.4) |

| Mean residual pressure gradient (echo), mmHg | 13.1 ± 5.5 |

| Mean residual gradient >20 mmHg | 3 (9.4) |

| NYHA I-II | 30 (93.7) |

| Dual antiplatelet therapy | 5 (15.6) |

| Oral anticoagulation | 15 (46.9) |

| Single antiplatelet therapy | 12 (37.5) |

| All-cause death * | 5 (15.6) |

| Cardiovascular death * | 3 (9.4) |

| Stroke * | 5 (15.6) |

| Need for surgical aortic valve replacement | 1 (3.1) |

| Pacemaker implantation | 0 (0) |

| New left bundle branch block | 3 (9.4) |

| Life-threatening bleeding/vascular complication | 1 (3.1) |

| Coronary obstruction | 0 (0) |

| Hospitalization due to heart failure | 3 (9.4) |

| Valve thrombosis | 1 (3.1) |

| Valve endocarditis ** | 1 (3.1) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jonik, S.; Mazurek, M.; Rymuza, B.; Jankowski, J.; Dąbrowski, M.; Wolny, R.; Chodór, P.; Wilczek, K.; Fil, W.; Milewski, K.; et al. Redo-Transcatheter Aortic Valve Implantation (Redo-TAVI)—Pilot Study from Multicentre Nationwide Registry. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 8078. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14228078

Jonik S, Mazurek M, Rymuza B, Jankowski J, Dąbrowski M, Wolny R, Chodór P, Wilczek K, Fil W, Milewski K, et al. Redo-Transcatheter Aortic Valve Implantation (Redo-TAVI)—Pilot Study from Multicentre Nationwide Registry. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(22):8078. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14228078

Chicago/Turabian StyleJonik, Szymon, Maciej Mazurek, Bartosz Rymuza, Jan Jankowski, Maciej Dąbrowski, Rafał Wolny, Piotr Chodór, Krzysztof Wilczek, Wojciech Fil, Krzysztof Milewski, and et al. 2025. "Redo-Transcatheter Aortic Valve Implantation (Redo-TAVI)—Pilot Study from Multicentre Nationwide Registry" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 22: 8078. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14228078

APA StyleJonik, S., Mazurek, M., Rymuza, B., Jankowski, J., Dąbrowski, M., Wolny, R., Chodór, P., Wilczek, K., Fil, W., Milewski, K., Protasiewicz, M., Ściborski, K., Kapłon-Cieślicka, A., Skrobucha, A., Hawranek, M., Scisło, P., Wilimski, R., Kochman, J., Grabowski, M., ... Huczek, Z. (2025). Redo-Transcatheter Aortic Valve Implantation (Redo-TAVI)—Pilot Study from Multicentre Nationwide Registry. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(22), 8078. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14228078