Blood Pressure Optimization During Fetoscopic Repair of Open Spinal Dysraphism: Insights from Advanced Hemodynamic Monitoring

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

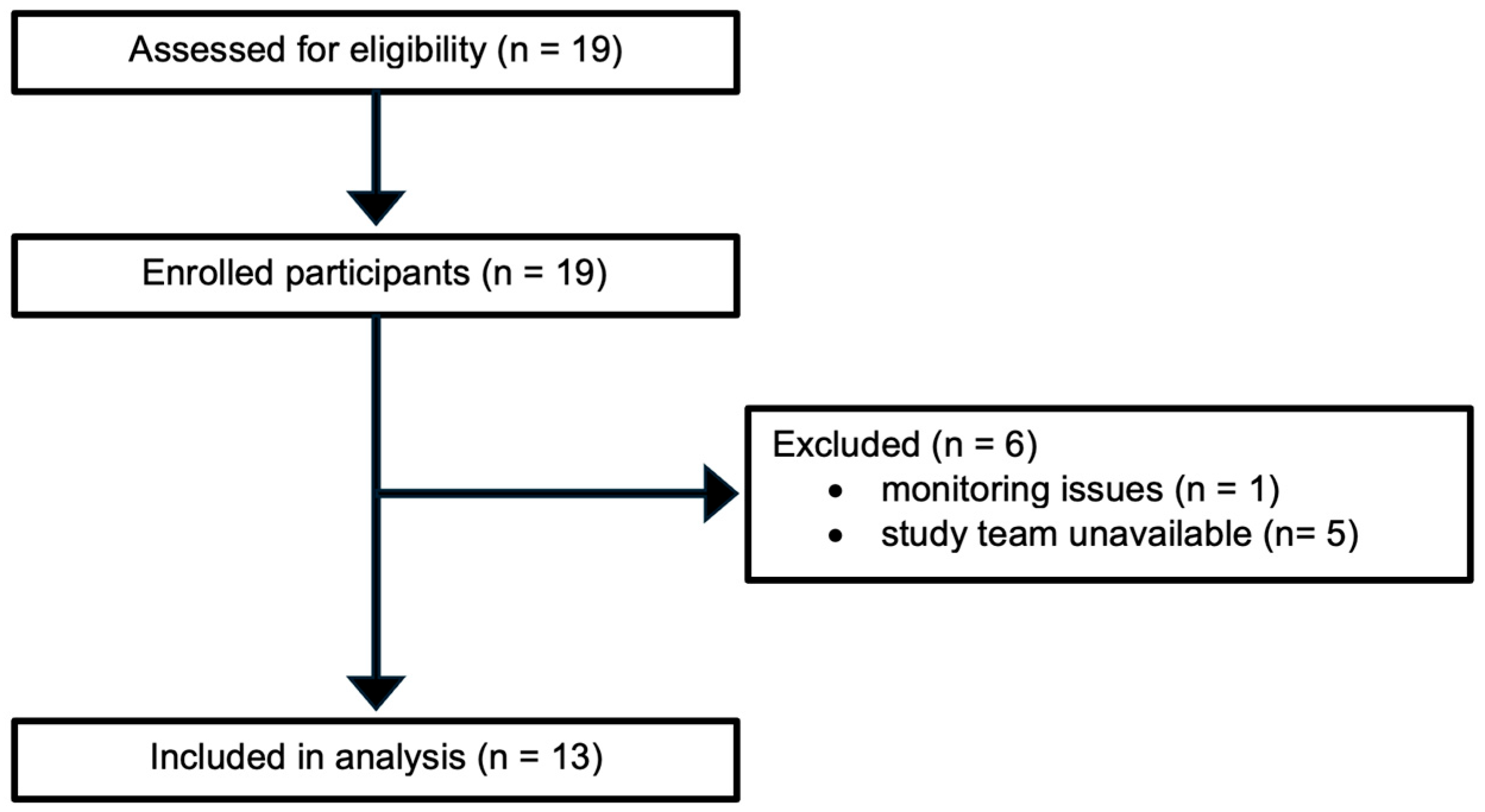

2.1. The Study Design and Setting

2.2. Advanced Hemodynamic Monitoring

2.3. Management of Intraoperative Hypotension

2.4. Assessment of Hemodynamic Response

2.5. Fetal Heart Rate

2.6. Aim of This Study

2.7. Statistical Analysis and Data Management

3. Results

3.1. Maternal Demographic and Clinical Characteristics

3.2. Anesthetic Management

4. Discussion

Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Declaration of Generative AI in Scientific Writing

Abbreviations

| bpm | beats per minute |

| C/T | cafedrine/theodrenaline |

| CI | cardiac index |

| CO | cardiac output |

| dP/dtmax | maximal rate of arterial pressure rise |

| FHR | fetal heart rate |

| HPI | Hypotension Prediction Index |

| HR | heart rate |

| IQR | interquartile range |

| MAP | mean arterial pressure |

| OSD | open spinal dysraphism |

| PPV | pulse pressure variation |

| PR | pulse rate |

| SVI | stroke volume index |

| SVRI | systemic vascular resistance index |

| SVV | stroke volume variation |

| TWA | time-weighted average |

References

- Keil, C.; Sass, B.; Schulze, M.; Kohler, S.; Axt-Fliedner, R.; Bedei, I. The Intrauterine Treatment of Open Spinal Dysraphism. Dtsch. Arztebl. Int. 2025, 122, 33–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Available online: https://eu-rd-platform.jrc.ec.europa.eu/eurocat/eurocat-data/prevalence_en (accessed on 16 August 2025).

- Meuli, M.; Meuli-Simmen, C.; Hutchins, G.M.; Seller, M.J.; Harrison, M.R.; Adzick, N.S. The spinal cord lesion in human fetuses with myelomeningocele: Implications for fetal surgery. J. Pediatr. Surg. 1997, 32, 448–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meuli, M.; Meuli-Simmen, C.; Yingling, C.D.; Hutchins, G.M.; Hoffman, K.M.; Harrison, M.R.; Adzick, N. Creation of myelomeningocele in utero: A model of functional damage from spinal cord exposure in fetal sheep. J. Pediatr. Surg. 1995, 30, 1028–1032, discussion 32–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keil, C.; Köhler, S.; Sass, B.; Schulze, M.; Kalmus, G.; Belfort, M.; Schmitt, N.; Diehl, D.; King, A.; Groß, S.; et al. Implementation and Assessment of a Laparotomy-Assisted Three-Port Fetoscopic Spina Bifida Repair Program. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 5151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben Miled, S.; Loeuillet, L.; Van Huyen, J.-P.D.; Bessières, B.; Sekour, A.; Leroy, B.; Tantau, J.; Adle-Biassette, H.; Salhi, H.; Bonnière-Darcy, M.; et al. Severe and progressive neuronal loss in myelomeningocele begins before 16 weeks of pregnancy. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2020, 223, 256.e1–256.e9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castillo, J.; Locastro, M.M.; Corroenne, R.; Malhotra, A.; Van Speybroeck, A.; Lai, G.; Belfort, M.A.; Cortes, M.S.; Castillo, H. Maternal-fetal surgery for myelomeningocele longitudinal follow-up model: Mitigation of care fragmentation through care coordination and outcomes reporting. J. Pediatr. Rehabil. Med. 2025, 18, 146–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adzick, N.S.; Thom, E.A.; Spong, C.Y.; Brock, J.W., III; Burrows, P.K.; Johnson, M.P.; Howell, L.J.; Farrell, J.A.; Dabrowiak, M.E.; Sutton, L.N.; et al. A randomized trial of prenatal versus postnatal repair of myelomeningocele. N. Engl. J. Med. 2011, 364, 993–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitt, N.; Schubert, A.K.; Wulf, H.; Keil, C.; Sutton, C.D.; Bedei, I.; Kalmus, G. Initial experience with the anaesthetic management of fetoscopic spina bifida repair at a German University Hospital: A case series of 15 patients. Eur. J. Anaesthesiol. Intensive Care 2024, 3, e0047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cortes, M.S.; Lapa, D.A.; Acácio, G.L.; Belfort, M.; Carreras, E.; Maiz, N.; Peiro, J.L.; Lim, F.Y.; Miller, J.; Baschat, A.; et al. Proceedings of the First Annual Meeting of the International Fetoscopic Myelomeningocele Repair Consortium. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 2019, 53, 855–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortes, M.S.; Chmait, R.H.; Lapa, D.A.; Belfort, M.A.; Carreras, E.; Miller, J.L.; Samaha, R.B.B.; Gonzalez, G.S.; Gielchinsky, Y.; Yamamoto, M.; et al. Experience of 300 cases of prenatal fetoscopic open spina bifida repair: Report of the International Fetoscopic Neural Tube Defect Repair Consortium. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2021, 225, 678.e1–678.e11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naus, C.A.; Mann, D.G.; Andropoulos, D.B.; Belfort, M.A.; Sanz-Cortes, M.; Whitehead, W.E.; Sutton, C.D. “This is how we do it” Maternal and fetal anesthetic management for fetoscopic myelomeningocele repairs: The Texas Children’s Fetal Center protocol. Int. J. Obstet. Anesth. 2025, 61, 104316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunpalin, Y.; Sahakyan, Y.; Sander, B.; Snelgrove, J.W.; Raghuram, K.; Kulkarni, A.V.; Van Mieghem, T. Comparison of open fetal, fetoscopic and postnatal surgical repair for open spina bifida: Decision analysis. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 2025, 66, 433–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miranda, J.; Parra-Saavedra, M.A.; Contreras-Lopez, W.O.; Abello, C.; Parra, G.; Hernandez, J.; Barrero, A.; Leones, I.; Nieto-Sanjuanero, A.; Sepúlveda-Gonzalez, G.; et al. Implementation of in utero laparotomy-assisted fetoscopic spina bifida repair in two centers in Latin America: Rationale for this approach in this region. AJOG Glob. Rep. 2025, 5, 100442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunpalin, Y.; Karadjole, V.S.; Medeiros, E.S.B.; Domínguez-Moreno, M.; Sichitiu, J.; Abbasi, N.; Ryan, G.; Shinar, S.; Snelgrove, J.W.; Kulkarni, A.V.; et al. Benefits and complications of fetal and postnatal surgery for open spina bifida: Systematic review and proportional meta-analysis. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 2025, 66, 135–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cruz, S.M.; Hameedi, S.; Sbragia, L.; Ogunleye, O.; Diefenbach, K.; Isaacs, A.M.; Etchegaray, A.; Olutoye, O.O. Fetoscopic Myelomeningocele (MMC) Repair: Evolution of the Technique and a Call for Standardization. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 1402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nulens, K.; Kunpalin, Y.; Nijs, K.; Carvalho, J.C.A.; Pollard, L.; Abbasi, N.; Ryan, G.; Van Mieghem, T. Enhanced recovery after fetal spina bifida surgery: Global practice. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 2024, 64, 669–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalkalitsis, A.; Zikopoulos, A.; Katrachouras, A.; Samara, I.; Gkrozou, F. Non-Cardiogenic Pulmonary Edema Due to Administration of Atosiban. Cureus 2023, 15, e36799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Z.; Wu, W.; Yu, Y.; Liu, H. Atosiban-induced acute pulmonary edema: A rare but severe complication of tocolysis. Heliyon 2023, 9, e15829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferschl, M.; Ball, R.; Lee, H.; Rollins, M.D. Anesthesia for in utero repair of myelomeningocele. Anesthesiology 2013, 118, 1211–1223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kranke, P.; Geldner, G.; Kienbaum, P.; Gerbershagen, H.J.; Chappell, D.; Wallenborn, J.; Huljic, S.; Koch, T.; Keller, T.; Weber, S.; et al. Treatment of spinal anaesthesia-induced hypotension with cafedrine/theodrenaline versus ephedrine during caesarean section: Results from HYPOTENS, a national, multicentre, prospective, noninterventional study. Eur. J. Anaesthesiol. 2021, 38, 1067–1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bremerich, D.H.; Greve, S. [The new S1 guidelines “Obstetric analgesia and anesthesia”-Presentation and comments]. Anaesthesist 2021, 70, 229–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wijnberge, M.; Geerts, B.F.; Hol, L.; Lemmers, N.; Mulder, M.P.; Berge, P.; Schenk, J.; Terwindt, L.E.; Hollmann, M.W.; Vlaar, A.P.; et al. Effect of a Machine Learning-Derived Early Warning System for Intraoperative Hypotension vs Standard Care on Depth and Duration of Intraoperative Hypotension During Elective Noncardiac Surgery: The HYPE Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA 2020, 323, 1052–1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneck, E.; Schulte, D.; Habig, L.; Ruhrmann, S.; Edinger, F.; Markmann, M.; Habicher, M.; Rickert, M.; Koch, C.; Sander, M. Hypotension Prediction Index based protocolized haemodynamic management reduces the incidence and duration of intraoperative hypotension in primary total hip arthroplasty: A single centre feasibility randomised blinded prospective interventional trial. J. Clin. Monit. Comput. 2020, 34, 1149–1158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hatib, F.; Jian, Z.; Buddi, S.; Lee, C.; Settels, J.; Sibert, K.; Rinehart, J.; Cannesson, M. Machine-learning Algorithm to Predict Hypotension Based on High-fidelity Arterial Pressure Waveform Analysis. Anesthesiology 2018, 129, 663–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davies, S.J.; Vistisen, S.T.; Jian, Z.; Hatib, F.; Scheeren, T.W.L. Ability of an Arterial Waveform Analysis-Derived Hypotension Prediction Index to Predict Future Hypotensive Events in Surgical Patients. Anesth. Analg. 2020, 130, 352–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kloth, B.; Pecha, S.; Moritz, E.; Schneeberger, Y.; Söhren, K.-D.; Schwedhelm, E.; Reichenspurner, H.; Eschenhagen, T.; Böger, R.H.; Christ, T.; et al. Akrinor(TM), a Cafedrine/ Theodrenaline Mixture (20:1), Increases Force of Contraction of Human Atrial Myocardium But Does Not Constrict Internal Mammary Artery In Vitro. Front. Pharmacol. 2017, 8, 272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bein, B.; Christ, T.; Eberhart, L.H. Cafedrine/Theodrenaline (20:1) Is an Established Alternative for the Management of Arterial Hypotension in Germany-a Review Based on a Systematic Literature Search. Front. Pharmacol. 2017, 8, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dings, C.; Lehr, T.; Vojnar, B.; Gaik, C.; Koch, T.; Eberhart, L.H.J.; Huljic-Lankinen, S.; Murst, M.; Kreuer, S. Population kinetic/pharmacodynamic modelling of the haemodynamic effects of cafedrine/theodrenaline (Akrinor) under general anaesthesia. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2024, 90, 1964–1974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heller, A.R.; Heger, J.; Gama de Abreu, M.; Muller, M.P. Cafedrine/theodrenaline in anaesthesia: Influencing factors in restoring arterial blood pressure. Anaesthesist 2015, 64, 190–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weitzel, M.; Hammels, P.; Schorer, C.; Klingler, H.; Weyland, A. [Hemodynamic effects of cafedrine/theodrenaline on anesthesia-induced hypotension]. Anaesthesist 2018, 67, 766–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zargarzadeh, N.; Sambatur, E.; Abiad, M.; Rojhani, E.; Javinani, A.; Northam, W.; Chmait, R.H.; Krispin, E.; Aagaard, K.; Shamshirsaz, A.A. Gestational age at birth varies by surgical technique in prenatal open spina bifida repair: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2025, 232, 524–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Damaty, A.; Elsässer, M.; Pfeifer, U.; Kotzaeridou, U.; Gille, C.; Spratte, J.; Zivanovic, O.; Sohn, C.; Krieg, S.M.; Bächli, H.; et al. The first experience with 16 open microsurgical fetal surgeries for myelomeningocele in Germany. Eur. J. Paediatr. Neurol. 2025, 55, 79–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dick, J.R.; Wimalasundera, R.; Nandi, R. Maternal and fetal anaesthesia for fetal surgery. Anaesthesia 2021, 76 (Suppl. S4), 63–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Winden, T.; Roos, C.; Mol, B.W.; Pajkrt, E.; Oudijk, M.A. A historical narrative review through the field of tocolysis in threatened preterm birth. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. X 2024, 22, 100313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valenzuela, G.J.; Craig, J.; Bernhardt, M.D.; Holland, M.L. Placental passage of the oxytocin antagonist atosiban. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 1995, 172 Pt 1, 1304–1306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine; Society of Family Planning; Norton, M.E.; Cassidy, A.; Ralston, S.J.; Chatterjee, D.; Farmer, D.; Beasley, A.D.; Dragoman, M. Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine Consult Series #59: The use of analgesia and anesthesia for maternal-fetal procedures. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2021, 225, B2–B8. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, J.; He, A.; Li, N.; Chen, X.; Zhou, X.; Fan, X.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, M.; Qi, L.; Tao, J.; et al. Magnesium Sulfate-Mediated Vascular Relaxation and Calcium Channel Activity in Placental Vessels Different From Nonplacental Vessels. J Am Heart Assoc 2018, 7, e009896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinsella, S.M.; Carvalho, B.; Dyer, R.A.; Fernando, R.; McDonnell, N.; Mercier, F.J.; Palanisamy, A.; Sia, A.T.H.; Van de Velde, M.; Vercueil, A.; et al. International consensus statement on the management of hypotension with vasopressors during caesarean section under spinal anaesthesia. Anaesthesia 2018, 73, 71–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngan Kee, W.D.; Khaw, K.S.; Tan, P.E.; Ng, F.F.; Karmakar, M.K. Placental transfer and fetal metabolic effects of phenylephrine and ephedrine during spinal anesthesia for cesarean delivery. Anesthesiology 2009, 111, 506–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, K.; Wang, X.; Feng, X.; Zhang, J.; Xiao, W.; Wang, F.; Zhou, Q.; Wang, T. Effects of continuous infusion of phenylephrine vs. norepinephrine on parturients and fetuses under LiDCOrapid monitoring: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. BMC Anesthesiol. 2020, 20, 229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mon, W.; Stewart, A.; Fernando, R.; Ashpole, K.; El-Wahab, N.; MacDonald, S.; Tamilselvan, P.; Columb, M.; Liu, Y. Cardiac output changes with phenylephrine and ephedrine infusions during spinal anesthesia for cesarean section: A randomized, double-blind trial. J. Clin. Anesth. 2017, 37, 43–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdallah, A.C.; Song, S.H.; Fleming, N.W. A retrospective study of the effects of a vasopressor bolus on systolic slope (dP/dt) and dynamic arterial elastance (Ea(dyn)). BMC Anesthesiol. 2024, 24, 257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teboul, J.L.; Monnet, X.; Chemla, D.; Michard, F. Arterial Pulse Pressure Variation with Mechanical Ventilation. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2019, 199, 22–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaves, R.C.d.F.; Barbas, C.S.V.; Queiroz, V.N.F.; Neto, A.S.; Deliberato, R.O.; Pereira, A.J.; Timenetsky, K.T.; Júnior, J.M.S.; Takaoka, F.; de Backer, D.; et al. Assessment of fluid responsiveness using pulse pressure variation, stroke volume variation, plethysmographic variability index, central venous pressure, and inferior vena cava variation in patients undergoing mechanical ventilation: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Crit. Care 2024, 28, 289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duron, V.D.; Watson-Smith, D.; Benzuly, S.E.; Muratore, C.S.; O’brien, B.M.; Carr, S.R.; Luks, F.I. Maternal and fetal safety of fluid-restrictive general anesthesia for endoscopic fetal surgery in monochorionic twin gestations. J. Clin. Anesth. 2014, 26, 184–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Refai, A.; Ryan, G.; Van Mieghem, T. Maternal risks of fetal therapy. Curr. Opin. Obstet. Gynecol. 2017, 29, 80–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saugel, B.; Kouz, K.; Scheeren, T.W.L. The ‘5 Ts’ of perioperative goal-directed haemodynamic therapy. Br. J. Anaesth. 2019, 123, 103–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rychik, J. Fetal cardiovascular physiology. Pediatr. Cardiol. 2004, 25, 201–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rudolph, A.M. The fetal circulation and its response to stress. J. Dev. Physiol. 1984, 6, 11–19. [Google Scholar]

- Kiserud, T.; Acharya, G. The fetal circulation. Prenat. Diagn. 2004, 24, 1049–1059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilbert, R.D. Control of fetal cardiac output during changes in blood volume. Am. J. Physiol. 1980, 238, H80–H86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Batra, A.S.; Silka, M.J.; Borquez, A.; Cuneo, B.; Dechert, B.; Jaeggi, E.; Kannankeril, P.J.; Tabulov, C.; Tisdale, J.E.; Wolfe, D. Pharmacological Management of Cardiac Arrhythmias in the Fetal and Neonatal Periods: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association: Endorsed by the Pediatric & Congenital Electrophysiology Society (PACES). Circulation 2024, 149, e937–e952. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Frassanito, L.; Sonnino, C.; Piersanti, A.; Zanfini, B.A.; Catarci, S.; Giuri, P.P.; Scorzoni, M.; Gonnella, G.L.; Antonelli, M.; Draisci, G. Performance of the Hypotension Prediction Index With Noninvasive Arterial Pressure Waveforms in Awake Cesarean Delivery Patients Under Spinal Anesthesia. Anesth. Analg. 2022, 134, 633–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Parameter | Median (IQR) |

|---|---|

| Anesthesia | |

| Sevoflurane, end-expiratory, n = 13 [Vol%] | 2.5 (2.1–2.8) |

| Remifentanil, n= 13 [µg] | 2990 (2290–4536) |

| Vasopressor therapy | |

| Norepinephrine infusion, n = 3 [µg] | 1530 (270–2490) |

| Cafedrine/theodrenaline bolus, n = 110 [mg] | 40 (40–40) |

| Tocolytic therapy | |

| Atosiban, n = 13 [mg/h] | 137 (63–187) |

| Magnesium sulfate, n = 10 [g/h] | 3.5 (2.6–3.8) |

| Volume therapy | |

| Human albumin 5%, n = 13 [mL] | 750 (500–1000) |

| Ringer’s acetate, n = 6 [mL] | 175 (150–350) |

| Urine output, n = 13 [mL] | 1600 (1200–1850) |

| Parameter | n | Prior Hypotension Management | After Hypotension Management | Percent Change | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cardiac Index [L/min/m2] | 110 | 3.6 [2.8–4.4] | 3.4 [2.7–4.0] | −6.7 [−11.8–−0.6] | <0.001 |

| Stroke Volume Index [mL/m2] | 110 | 46 [38–54] | 43 [38–51] | −4.3 [−9.8–1.8] | 0.048 |

| Maternal Pulse Rate [bpm] | 110 | 78 [73–83] | 78 [71–85] | −0.5 [−4.0–1.6] | 0.670 |

| Systolic Pressure [mmHg] | 110 | 101 [95–108] | 114 [107–125] | 13.9 [5.8–20.5] | <0.001 |

| Diastolic Pressure [mmHg] | 110 | 56 [51–60] | 63 [55–68] | 12.0 [4.5–18.7] | <0.001 |

| Mean Arterial Pressure [mmHg] | 110 | 70 [65–75] | 78 [70–86] | 13.7 [5.9–21.6] | <0.001 |

| Systemic Vascular Resistance Index [dyn·s·cm−5·m2] | 105 | 1420 [1139–1760.9] | 1670 [1473–1999] | 23.1 [8.3–36.7] | <0.001 |

| Stroke Volume Variation [%] | 110 | 6.7 [5.6–8.0] | 6.0 [4.3–8.0] | −11.9 [−25.2–−3.7] | 0.014 |

| Pulse Pressure Variation [%] | 110 | 8.1 [6.8–10.3] | 7.0 [5.7–9.3] | −12.7 [−25.2–0.0] | 0.006 |

| Rate of arterial pressure rise [mmHg/s] | 110 | 745 [620–841] | 886 [705–1000] | 21.7 [6.3–29.9] | <0.001 |

| Eadyn (PPV/SVV) | 110 | 1.3 [1.1–1.4] | 1.3 [1.1–1.5] | 1.2 [−9.4–15.2] | 0.852 |

| Fetal Heart Rate [bpm] | 34 | 128 [121–133] | 128 [119–136] | 0.4 [−0.8–1.5] | 0.470 |

| Hypotension Metrics | Value |

|---|---|

| Total monitoring time of the cohort | 5350.67 min |

| Monitoring time per patient | 411.59 ± 32.93 min |

| Number of patients with hypotension | 8 of 13 (61.54%) |

| Total number of hypotensive events | 96 events |

| Average number of hypotensive events per patient | 7.38 ± 9.29 |

| Average duration of each hypotensive event | 6.39 ± 10.73 min |

| Mean MAP under 65 mmHg per patient | 58.27 ± 13.07 mmHg |

| Time-weighted average of area under threshold (MAP < 65 mmHg) per patient | 0.44 ± 0.95 mmHg |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Vojnar, B.; Belfort, M.; Sutton, C.D.; Keil, C.; Bedei, I.; Kalmus, G.; Wulf, H.; Köhler, S.; Gaik, C. Blood Pressure Optimization During Fetoscopic Repair of Open Spinal Dysraphism: Insights from Advanced Hemodynamic Monitoring. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 8055. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14228055

Vojnar B, Belfort M, Sutton CD, Keil C, Bedei I, Kalmus G, Wulf H, Köhler S, Gaik C. Blood Pressure Optimization During Fetoscopic Repair of Open Spinal Dysraphism: Insights from Advanced Hemodynamic Monitoring. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(22):8055. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14228055

Chicago/Turabian StyleVojnar, Benjamin, Michael Belfort, Caitlin D. Sutton, Corinna Keil, Ivonne Bedei, Gerald Kalmus, Hinnerk Wulf, Siegmund Köhler, and Christine Gaik. 2025. "Blood Pressure Optimization During Fetoscopic Repair of Open Spinal Dysraphism: Insights from Advanced Hemodynamic Monitoring" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 22: 8055. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14228055

APA StyleVojnar, B., Belfort, M., Sutton, C. D., Keil, C., Bedei, I., Kalmus, G., Wulf, H., Köhler, S., & Gaik, C. (2025). Blood Pressure Optimization During Fetoscopic Repair of Open Spinal Dysraphism: Insights from Advanced Hemodynamic Monitoring. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(22), 8055. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14228055