Force Reversal During Systolic–Diastolic Transition Provides Incremental Prognostic Value over LVEF for Heart Failure After STEMI

Abstract

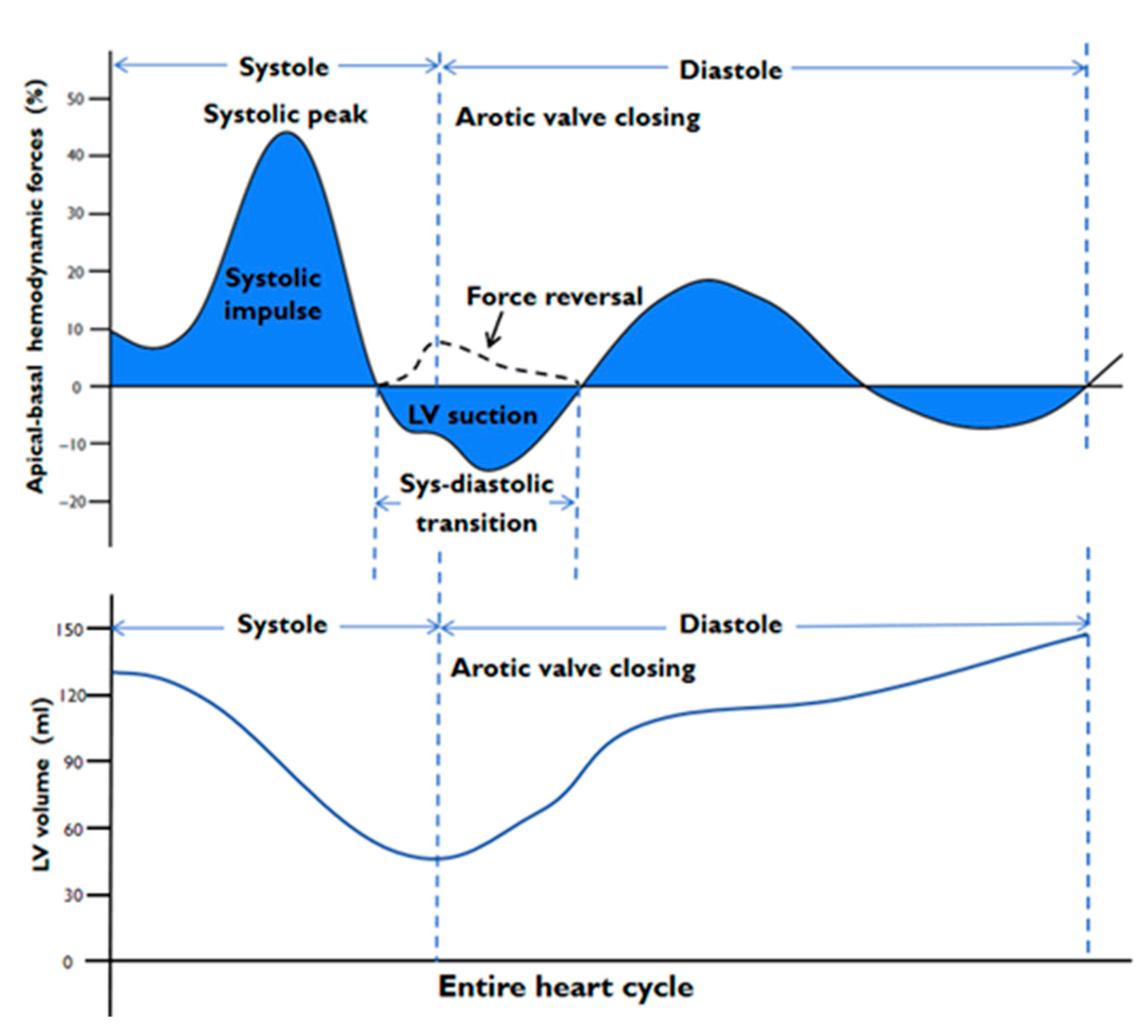

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. CMR Acquisition

2.2. CMR Image Analysis

2.3. Follow-Up

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Patients’ Baseline and Clinical Characteristics

3.2. The Association Between Left Ventricular Hemodynamic Forces and Infarct Location

3.3. The Association Between Left Ventricular Hemodynamic Forces and Infarct Size

3.4. Univariable and Multivariable Predictors of Force Reversal in Systolic–Diastolic Transition

3.5. Incremental Value of Force Reversal for Predicting HF in Patients with STEMI

3.6. Reproducibility Evaluation

4. Discussion

Limitations of the Study

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| STEMI | ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction |

| CMR | Cardiac magnetic resonance |

| LVEF | Left ventricular ejection fraction |

| IVPGs | Intraventricular pressure gradients |

| HDFs | Hemodynamic forces |

| LGE | Late gadolinium enhancement |

| EDV | End-diastolic volume |

| ESV | End-systolic volume |

| IS | Infarct size |

| MVO | Microvascular obstruction |

| GLS | Global longitudinal strain |

| GCS | Global circumferential strain |

| PCI | Percutaneous coronary intervention |

| ECG | Electrocardiogram |

| bSSFP | Balanced steady-state free precession |

| A–B | Apical–basal |

| L–S | Lateral–septal |

| RMS | Root mean square |

| SD | Standard deviation |

| IQR | Interquartile range |

| ICC | Intraclass correlation coefficient |

| VIF | Variance inflation factor |

| CI | Confidence intervals |

References

- Arvidsson, P.M.; Töger, J.; Carlsson, M.; Steding-Ehrenborg, K.; Pedrizzetti, G.; Heiberg, E.; Arheden, H. Left and right ventricular hemodynamic forces in healthy volunteers and elite athletes assessed with 4D flow magnetic resonance imaging. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2017, 312, H314–H328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arvidsson, P.M.; Töger, J.; Pedrizzetti, G.; Heiberg, E.; Borgquist, R.; Carlsson, M.; Arheden, H. Hemodynamic forces using four-dimensional flow MRI: An independent biomarker of cardiac function in heart failure with left ventricular dyssynchrony? Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2018, 315, H1627–H1639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lapinskas, T.; Pedrizzetti, G.; Stoiber, L.; Düngen, H.D.; Edelmann, F.; Pieske, B.; Kelle, S. The Intraventricular Hemodynamic Forces Estimated Using Routine CMR Cine Images: A New Marker of the Failing Heart. JACC Cardiovasc. Imaging 2019, 12, 377–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedrizzetti, G.; Martiniello, A.R.; Bianchi, V.; D’Onofrio, A.; Caso, P.; Tonti, G. Changes in electrical activation modify the orientation of left ventricular flow momentum: Novel observations using echocardiographic particle image velocimetry. Eur. Heart J. Cardiovasc. Imaging 2016, 17, 203–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vos, J.L.; Raafs, A.G.; Henkens, M.; Pedrizzetti, G.; van Deursen, C.J.; Rodwell, L.; Heymans, S.R.B.; Nijveldt, R. CMR-derived left ventricular intraventricular pressure gradients identify different patterns associated with prognosis in dilated cardiomyopathy. Eur. Heart J. Cardiovasc. Imaging 2023, 24, 1231–1240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vos, J.L.; Leiner, T.; van Dijk, A.P.J.; Pedrizzetti, G.; Alenezi, F.; Rodwell, L.; van der Wegen, C.; Post, M.C.; Driessen, M.M.P.; Nijveldt, R. Cardiovascular magnetic resonance-derived left ventricular intraventricular pressure gradients among patients with precapillary pulmonary hypertension. Eur. Heart J. Cardiovasc. Imaging 2022, 24, 78–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedrizzetti, G.; Martiniello, A.R.; Bianchi, V.; D’Onofrio, A.; Caso, P.; Tonti, G. Cardiac fluid dynamics anticipates heart adaptation. J. Biomech. 2015, 48, 388–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vallelonga, F.; Airale, L.; Tonti, G.; Argulian, E.; Milan, A.; Narula, J.; Pedrizzetti, G. Introduction to Hemodynamic Forces Analysis: Moving Into the New Frontier of Cardiac Deformation Analysis. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2021, 10, e023417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pedrizzetti, G. On the computation of hemodynamic forces in the heart chambers. J. Biomech. 2019, 95, 109323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pedrizzetti, G.; Arvidsson, P.M.; Töger, J.; Borgquist, R.; Domenichini, F.; Arheden, H.; Heiberg, E. On estimating intraventricular hemodynamic forces from endocardial dynamics: A comparative study with 4D flow MRI. J. Biomech. 2017, 60, 203–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filomena, D.; Cimino, S.; Monosilio, S.; Galea, N.; Mancuso, G.; Francone, M.; Tonti, G.; Pedrizzetti, G.; Maestrini, V.; Fedele, F.; et al. Impact of intraventricular haemodynamic forces misalignment on left ventricular remodelling after myocardial infarction. ESC Heart Fail. 2022, 9, 496–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eriksson, J.; Bolger, A.F.; Ebbers, T.; Carlhall, C.J. Left ventricular hemodynamic forces are altered in patients with dilated cardiomyopathy. J. Cardiovasc. Magn. Reson. 2015, 17, P282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Backhaus, S.J.; Uzun, H.; Rösel, S.F.; Schulz, A.; Lange, T.; Crawley, R.J.; Evertz, R.; Hasenfuß, G.; Schuster, A. Hemodynamic force assessment by cardiovascular magnetic resonance in HFpEF: A case-control substudy from the HFpEF stress trial. eBioMedicine 2022, 86, 104334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergamaschi, L.; Landi, A.; Maurizi, N.; Pizzi, C.; Leo, L.A.; Arangalage, D.; Iglesias, J.F.; Eeckhout, E.; Schwitter, J.; Valgimigli, M.; et al. Acute Response of the Noninfarcted Myocardium and Surrounding Tissue Assessed by T2 Mapping After STEMI. JACC Cardiovasc. Imaging 2024, 17, 610–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dal Ferro, M.; De Paris, V.; Collia, D.; Stolfo, D.; Caiffa, T.; Barbati, G.; Korcova, R.; Pinamonti, B.; Zovatto, L.; Zecchin, M.; et al. Left Ventricular Response to Cardiac Resynchronization Therapy: Insights From Hemodynamic Forces Computed by Speckle Tracking. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2019, 6, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacquier, A.; Boussel, L.; Amabile, N.; Bartoli, J.M.; Douek, P.; Moulin, G.; Paganelli, F.; Saeed, M.; Revel, D.; Croisille, P. Multidetector computed tomography in reperfused acute myocardial infarction. Assessment of infarct size and no-reflow in comparison with cardiac magnetic resonance imaging. Investig. Radiol. 2008, 43, 773–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, G.; Zhao, L.; Hui, K.; Lu, Z.; Zhang, X.; Gao, H.; Ma, X. Angiography-Derived Microcirculatory Resistance in Detecting Microvascular Obstruction and Predicting Heart Failure After STEMI. Circ. Cardiovasc. Imaging 2025, 18, e017506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hou, Y.; Zhou, H.; Li, Y.; Mao, T.; Luo, J.; Yang, J. Hemodynamic Force Based on Cardiac Magnetic Resonance Imaging: State of the Art and Perspective. J. Magn. Reson. Imaging 2025, 61, 1033–1047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reindl, M.; Reinstadler, S.J.; Feistritzer, H.J.; Theurl, M.; Basic, D.; Eigler, C.; Holzknecht, M.; Mair, J.; Mayr, A.; Klug, G.; et al. Relation of Low-Density Lipoprotein Cholesterol With Microvascular Injury and Clinical Outcome in Revascularized ST-Elevation Myocardial Infarction. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2017, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeLong, E.R.; DeLong, D.M.; Clarke-Pearson, D.L. Comparing the areas under two or more correlated receiver operating characteristic curves: A nonparametric approach. Biometrics 1988, 44, 837–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koo, T.K.; Li, M.Y. A Guideline of Selecting and Reporting Intraclass Correlation Coefficients for Reliability Research. J. Chiropr. Med. 2016, 15, 155–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismailov, T.; Khamitova, Z.; Jumadilova, D.; Khissamutdinov, N.; Toktarbay, B.; Zholshybek, N.; Rakhmanov, Y.; Salustri, A. Reliability of left ventricular hemodynamic forces derived from feature-tracking cardiac magnetic resonance. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0306481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lange, T.; Backhaus, S.J.; Schulz, A.; Evertz, R.; Schneider, P.; Kowallick, J.T.; Hasenfuß, G.; Kelle, S.; Schuster, A. Inter-study reproducibility of cardiovascular magnetic resonance-derived hemodynamic force assessments. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Masci, P.G.; Ganame, J.; Francone, M.; Desmet, W.; Lorenzoni, V.; Iacucci, I.; Barison, A.; Carbone, I.; Lombardi, M.; Agati, L.; et al. Relationship between location and size of myocardial infarction and their reciprocal influences on post-infarction left ventricular remodelling. Eur. Heart J. 2011, 32, 1640–1648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Backhaus, S.J.; Kowallick, J.T.; Stiermaier, T.; Lange, T.; Koschalka, A.; Navarra, J.L.; Lotz, J.; Kutty, S.; Bigalke, B.; Gutberlet, M.; et al. Culprit vessel-related myocardial mechanics and prognostic implications following acute myocardial infarction. Clin. Res. Cardiol. 2020, 109, 339–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Son, J.W.; Park, W.J.; Choi, J.H.; Houle, H.; Vannan, M.A.; Hong, G.R.; Chung, N. Abnormal left ventricular vortex flow patterns in association with left ventricular apical thrombus formation in patients with anterior myocardial infarction: A quantitative analysis by contrast echocardiography. Circ. J. 2012, 76, 2640–2646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spadafora, L.; Pastena, P.; Cacciatore, S.; Betti, M.; Biondi-Zoccai, G.; D’Ascenzo, F.; De Ferrari, G.M.; De Filippo, O.; Versaci, F.; Sciarretta, S.; et al. One-Year Prognostic Differences and Management Strategies between ST-Elevation and Non-ST-Elevation Myocardial Infarction: Insights from the PRAISE Registry. Am. J. Cardiovasc. Drugs 2025, 25, 681–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| STEMI Patients N = 275 | |

|---|---|

| Age, median (IQR), years | 58 (49–67) |

| Male, % | 229 (83%) |

| Cardiovascular risk factors | |

| Smoking, % | 174 (63%) |

| Hypertension, % | 166 (60%) |

| Hyperlipoproteinemia, % | 255 (92%) |

| Diabetes mellitus, % | 88 (32%) |

| BMI, median (IQR), kg/m2 | 26.0 (24.2–28.3) |

| SBP, median (IQR), mm Hg | 122 (110–132) |

| DBP, median (IQR), mm Hg | 75 (68–80) |

| Heart rate, median (IQR), beats/min | 76 (70–84) |

| Anterior STEMI, n (%) | 143 (52%) |

| Stent implanted | 228 (82%) |

| Infarct-related artery | |

| Left anterior descending | 142 (52%) |

| Left circumflex | 33 (12%) |

| Right coronary | 100 (36%) |

| Number of diseased vessels | |

| 1 | 107 (39%) |

| 2 | 73 (27%) |

| 3 | 95 (34%) |

| Killip class on admission | |

| 1 | 202 (74%) |

| 2 | 56 (20%) |

| 3 | 5 (2%) |

| 4 | 12 (4%) |

| TIMI flow grade before PCI | |

| 0 | 175 (64%) |

| 1 | 13 (5%) |

| 2 | 29 (10%) |

| 3 | 58 (21%) |

| TIMI flow grade post-PCI | |

| 0 | 2 (1%) |

| 1 | 2 (1%) |

| 2 | 7 (2%) |

| 3 | 264 (96%) |

| Parameter | STEMI Patients N = 275 | Anterior STEMI N = 143 | Non-Anterior STEMI N = 132 | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GLS (%) | −15.2 (−19.8, −10.8) | −11.6 (−15.3, −8.0) | −18.7 (−22.0, −15.4) | <0.001 |

| GCS (%) | −24.1 ± 7.8 | −23.2 ± 8.1 | −25.0 ± 7.4 | 0.062 |

| EDV (mL) | 139.1 (112.4, 167.5) | 143.2 (115.5, 172.2) | 134.4 (110.8, 164.0) | 0.052 |

| ESV (mL) | 67.9 (45.9, 92.5) | 71.6 (49.5, 103.6) | 63.6 (45.0, 82.2) | 0.007 |

| LVEF (%) | 50.5 ± 12.1 | 47.9 ± 13.1 | 52.8 ± 10.7 | 0.001 |

| IS (%) | 34.0 ± 15.3 | 37.2 ± 16.1 | 30.5 ± 13.6 | <0.001 |

| MVO (%) | 1.4 (0, 5.0) | 1.5 (0.2, 5.7) | 1.3 (0, 4.9) | 0.232 |

| HDFs: entire heart cycle | ||||

| A-B (%) (RMS) | 11.2 (8.1, 15.5) | 10.4 (7.3, 14.8) | 11.8 (8.8, 16.2) | 0.032 |

| L-S (%) (RMS) | 2.7 (2.0, 3.4) | 2.5 (1.9, 3.2) | 2.9 (2.2, 3.7) | 0.003 |

| L-S/A-B HDFs ratio (%) | 25.0 (19.1, 29.4) | 24.7 (19.0, 29.2) | 25.3 (19.1, 29.4) | 0.611 |

| Angle φ (°) | 70 (67, 74) | 70 (67, 74) | 71 (67, 74) | 0.533 |

| HDFs: systole | ||||

| A-B (%) (RMS) | 13.1 (8.7, 18.6) | 12.8 (8.5, 18.0) | 13.2 (9.0, 19.3) | 0.400 |

| L-S (%) (RMS) | 2.4 (1.8, 3.2) | 2.3 (1.6, 3.1) | 2.4 (1.9, 3.3) | 0.046 |

| L-S/A-B HDFs ratio (%) | 19.0 (13.9, 25.4) | 18.8 (13.9, 24.3) | 19.3 (13.9, 26.4) | 0.608 |

| Angle φ (°) | 74 (69, 77) | 74 (70, 77) | 73 (69, 76) | 0.249 |

| Systolic impulse (%) | 12.2 (8.2, 18.2) | 12.0 (8.0, 17.0) | 12.9 (8.4, 18.8) | 0.312 |

| Systolic peak (%) | 24.4 (16.9, 35.4) | 24.2 (17.0, 33.9) | 25.5 (16.9, 35.4) | 0.490 |

| HDFs: systolic–diastolic transition | ||||

| A-B (%) (RMS) | 6.6 (4.4, 10.2) | 6.0 (3.9, 9.5) | 7.2 (4.6, 10.8) | 0.049 |

| L-S (%) (RMS) | 3.5 (2.3, 4.8) | 3.0 (1.8, 3.9) | 3.9 (2.9, 5.6) | <0.001 |

| L-S/A-B HDFs ratio (%) | 52.0 (36.5, 68.6) | 49.6 (33.4, 66.5) | 53.4 (39.6, 72.0) | 0.073 |

| Angle φ (°) | 60 (54, 66) | 61 (56, 67) | 60 (55, 62) | 0.288 |

| LV suction (%) | −5.1 (−8.1, −3.3) | −4.8 (−7.4, −3.1) | −5.7 (−8.8, −3.7) | 0.056 |

| Force reversal (%) | 53 (19%) | 36 (25%) | 17 (13%) | 0.01 |

| HDFs: diastole | ||||

| A-B (%) (RMS) | 8.0 (5.5, 10.9) | 7.3 (5.0, 10.2) | 8.4 (6.3, 11.6) | 0.008 |

| L-S (%) (RMS) | 2.7 (1.9, 3.7) | 2.6 (1.8, 3.1) | 3.0 (2.1, 4.0) | <0.001 |

| L-S/A-B HDFs ratio (%) | 34.9 (25.8, 44.5) | 35.9 (25.6, 43.0) | 34.5 (26.0, 46.4) | 0.681 |

| Angle φ (°) | 68 (63, 72) | 68 (63, 72) | 67 (63, 72) | 0.647 |

| Parameter | STEMI Patients N = 275 | IS < 33.88 N = 137 | IS ≥ 33.88 N = 138 | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GLS (%) | −15.2 (−19.8, −10.8) | −17.4 (−21.7, −13.4) | −12.6 (−17.2, −8.3) | <0.001 |

| GCS (%) | −24.1 ± 7.8 | −26.7 ± 7.5 | −21.5 ± 7.3 | <0.001 |

| LVEF (%) | 139.1 (112.4, 167.5) | 55.8 (48.6, 62.9) | 46.6 (37.2, 54.3) | <0.001 |

| EDV (mL) | 67.9 (45.9, 92.5) | 132.1 (105.6, 154.7) | 146.5 (117.5, 172.6) | 0.001 |

| ESV (mL) | 50.5 ± 12.1 | 55.9 (42.8, 72.6) | 77.3 (55.5, 102.9) | <0.001 |

| IS (%) | 34.0 ± 15.3 | 24.1 (15.4, 28.7) | 43.8 (38.3, 51.1) | <0.001 |

| MVO (%) | 1.4 (0, 5.0) | 0.3 (0, 2.4) | 3.6 (0.7, 8.1) | <0.001 |

| Anterior STEMI | 143 (52%) | 60 (43.8%) | 83 (60.1%) | 0.007 |

| HDFs: entire heart cycle | ||||

| A-B (%) (RMS) | 11.2 (8.1, 15.5) | 12.4 (8.9, 16.7) | 10.3 (7.3, 13.5) | 0.002 |

| L-S (%) (RMS) | 2.7 (2.0, 3.4) | 2.8 (2.1, 3.8) | 2.6 (1.9, 3.3) | 0.073 |

| L-S/A-B HDFs ratio (%) | 25.0 (19.1, 29.4) | 23.9 (18.6, 28.0) | 26.0 (20.7, 30.3) | 0.025 |

| Angle φ (°) | 70 (67, 74) | 71 (68, 74) | 69 (66, 72) | 0.003 |

| HDFs: systole | ||||

| A-B (%) (RMS) | 13.1 (8.7, 18.6) | 14.0 (9.9, 21.3) | 11.8 (7.9, 15.6) | 0.002 |

| L-S (%) (RMS) | 2.4 (1.8, 3.2) | 2.4 (1.8, 3.3) | 2.3 (1.7, 3.2) | 0.565 |

| L-S/A-B HDFs ratio (%) | 19.0 (13.9, 25.4) | 17.5 (12.9, 22.7) | 20.1 (15.6, 27.0) | 0.002 |

| Angle φ (°) | 74 (69, 77) | 75 (71, 78) | 73 (68, 76) | 0.001 |

| Systolic impulse (%) | 12.2 (8.2, 18.2) | 14.2 (9.8, 20.7) | 10.7 (7.4, 15.5) | <0.001 |

| Systolic peak (%) | 24.4 (16.9, 35.4) | 26.7 (18.7, 40.6) | 22.1 (15.1, 30.6) | 0.003 |

| HDFs: systolic–diastolic transition | ||||

| A-B (%) (RMS) | 6.6 (4.4, 10.2) | 7.5 (5.0, 11.3) | 5.7 (3.8, 9.0) | 0.003 |

| L-S (%) (RMS) | 3.5 (2.3, 4.8) | 3.9 (2.6, 5.4) | 3.2 (2.0, 4.4) | 0.002 |

| L-S/A-B HDFs ratio (%) | 52.0 (36.5, 68.6) | 51.3 (36.4, 68.7) | 51.0 (34.1, 66.5) | 0.840 |

| Angle φ (°) | 60 (54, 66) | 60 (54, 66) | 59 (54, 66) | 0.997 |

| LV suction (%) | −5.1 (−8.1, −3.3) | −5.7 (−8.8, −3.9) | −4.6 (−7.1, −3.0) | 0.006 |

| Force reversal (%) | 53 (19%) | 23 (17%) | 30 (22%) | 0.298 |

| HDFs: diastole | ||||

| A-B (%) (RMS) | 8.0 (5.5, 10.9) | 8.3 (6.5, 11.6) | 7.2 (5.0, 9.8) | 0.011 |

| L-S (%) (RMS) | 2.7 (1.9, 3.7) | 2.9 (1.9, 3.9) | 2.6 (1.8, 3.4) | 0.098 |

| L-S/A-B HDFs ratio (%) | 34.9 (25.8, 44.5) | 33.8 (25.2, 45.0) | 36.8 (26.1, 44.5) | 0.260 |

| Angle φ (°) | 68 (63, 72) | 68 (63, 73) | 67 (63, 71) | 0.071 |

| Variable | Univariable | Stepwise Multivariable | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | p Value | OR (95% CI) | p Value | OR (95% CI) | p Value | |

| Anterior STEMI | 2.27 (1.20–4.29) | 0.011 | 2.22 (1.02–4.82) | 0.044 | 2.31 (1.05–5.07) | 0.036 |

| GLS | 1.05 (1.00–1.10) | 0.03 | 0.98 (0.90–1.07) | 0.791 | 0.98 (0.91–1.06) | 0.772 |

| GCS † | 1.04 (1.00–1.08) | 0.03 | n.a. | 1.03 (0.97–1.09) | 0.245 | |

| LVEF † | 0.97 (0.95–0.99) | 0.028 | 0.98 (0.94–1.02) | 0.363 | n.a. | |

| IS | 1.01 (0.99–1.03) | 0.065 | 0.99 (0.97–1.02) | 0.849 | 0.99 (0.97–1.02) | 0.798 |

| MVO | 1.06 (1.00–1.12) | 0.023 | 1.05 (0.98–1.13) | 0.146 | 1.05 (0.98–1.13) | 0.154 |

| Variables | Univariable | Stepwise Multivariable | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95% CI) | p Value | HR (95% CI) | p Value | HR (95% CI) | p Value | |

| Force reversal | 2.10 (1.22–3.62) | 0.007 | — | — | ||

| Anterior STEMI | 3.47 (1.91–6.31) | <0.001 | — | — | ||

| GCS † | 1.09 (1.05–1.12) | <0.001 | n.a. | — | ||

| GLS | 1.12 (1.09–1.15) | <0.001 | 1.09 (1.06–1.13) | <0.001 | 1.09 (1.06–1.13) | <0.001 |

| LVEF † | 0.94 (0.92–0.96) | <0.001 | — | n.a. | ||

| IS | 1.05 (1.03–1.06) | <0.001 | 1.03 (1.02–1.05) | <0.001 | 1.03 (1.02–1.05) | 0.004 |

| MVO | 1.08 (1.04–1.12) | <0.001 | — | — | ||

| C-Statistic (95% CI) | p Value | |

|---|---|---|

| Model 1 (LVEF) | 0.680 (0.610–0.747) | — |

| Model 2 (IS) | 0.717 (0.649–0.786) | — |

| Model 3 (GLS) | 0.777 (0.726–0.827) | — |

| Model 4 (Anterior STEMI) | 0.641 (0.584–0.697) | — |

| Model 5 (Force reversal) | 0.626 (0.546–0.686) | — |

| Model 6 (Force reversal + LVEF) | 0.770 (0.721–0.819) | 0.034 Model 6 vs. Model 1 |

| Model 7 (Force reversal + IS) | 0.760 (0.697–0.823) | 0.367 Model 7 vs. Model 2 |

| Model 8 (Force reversal + GLS) | 0.816 (0.775–0.858) | 0.237 Model 8 vs. Model 3 |

| Model 9 (Force reversal + Anterior STEMI) | 0.702 (0.641–0.764) | 0.146 Model 9 vs. Model 4 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sun, Y.; Wu, X.; Li, L.; Li, T.; Wang, Z.; Yu, W. Force Reversal During Systolic–Diastolic Transition Provides Incremental Prognostic Value over LVEF for Heart Failure After STEMI. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 7978. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14227978

Sun Y, Wu X, Li L, Li T, Wang Z, Yu W. Force Reversal During Systolic–Diastolic Transition Provides Incremental Prognostic Value over LVEF for Heart Failure After STEMI. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(22):7978. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14227978

Chicago/Turabian StyleSun, Yumeng, Xinyu Wu, Lu Li, Tingting Li, Zhenjia Wang, and Wei Yu. 2025. "Force Reversal During Systolic–Diastolic Transition Provides Incremental Prognostic Value over LVEF for Heart Failure After STEMI" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 22: 7978. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14227978

APA StyleSun, Y., Wu, X., Li, L., Li, T., Wang, Z., & Yu, W. (2025). Force Reversal During Systolic–Diastolic Transition Provides Incremental Prognostic Value over LVEF for Heart Failure After STEMI. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(22), 7978. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14227978