The Effect of Standard Concentration Infusions on Medication Errors in Neonatal and Pediatric Healthcare Settings: A Systematic Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Protocol and Registration

2.2. Eligibility Criteria and Definitions

2.3. Information Source

2.4. Search Strategy

2.5. Study Selection

2.6. Data Extraction and Calculation

2.7. Risk of Bias in Individual Studies

2.8. Summary Measures

2.9. Synthesis of Results

2.10. Risk of Bias Across Studies

2.11. Additional Analyses

| First Author (Country, Year) | Study Design, Study Center | Setting | Methods | Interventions | Measured Outcome | Results | Relative Risk Reduction |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

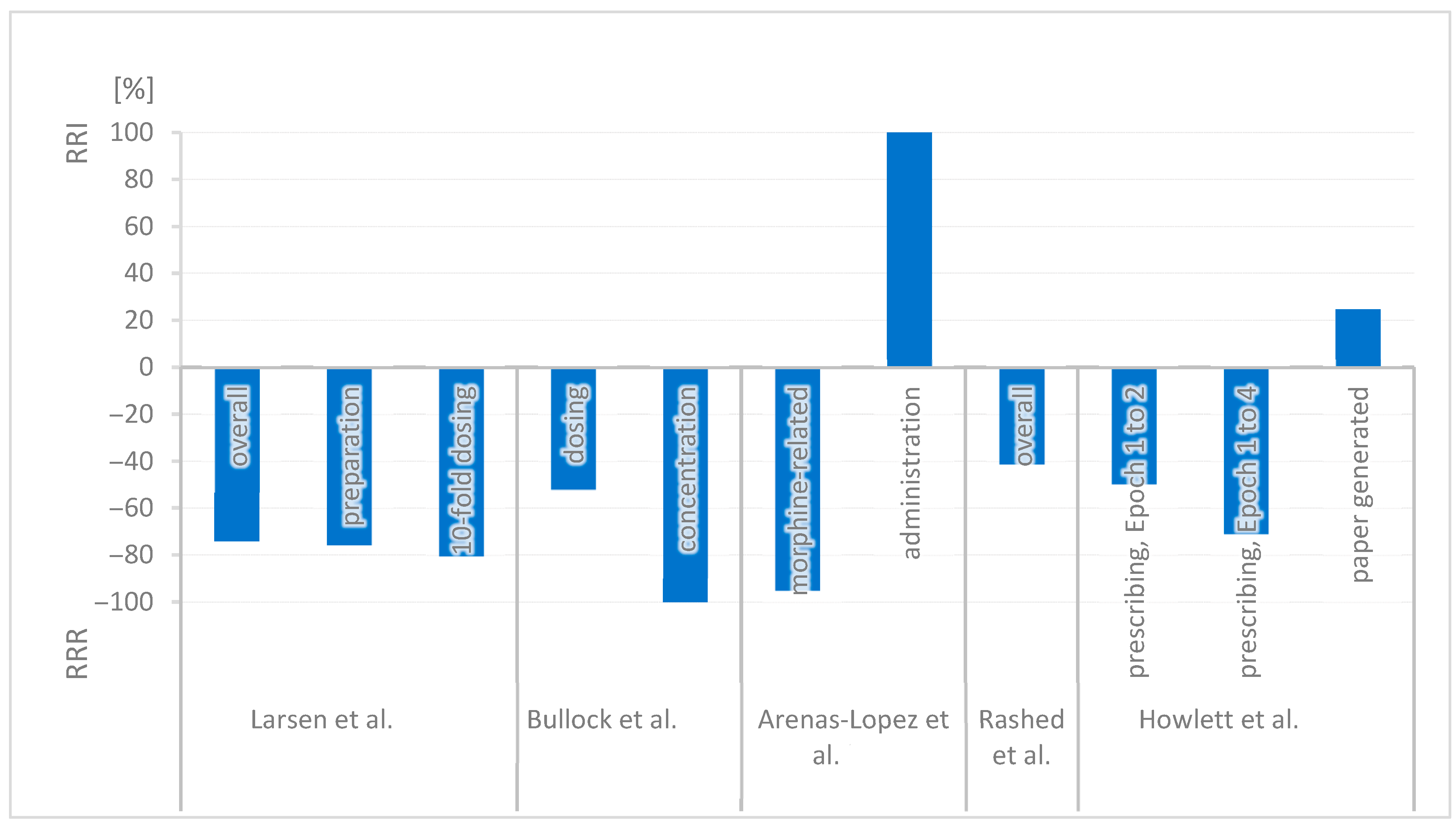

| G. Larsen et al. (USA, 2005) [22] | UBA, single center | Pediatric hospital | Evaluation of reported medication errors in infusion therapies in 2002 (pre-implementation) and 2003 (post-implementation) |

| Errors affecting standard concentrations and infusion pumps | The error rate was reduced from 3.1 to 0.8 per 1000 doses. (p < 0.001) Preparation errors in pharmacy were reduced from 0.66 to 0.16 per 1000 doses. 10-fold dosing errors were reduced from 0.41 to 0.08 per 1000 doses. | Overall: 74.2% (p < 0.001) Preparation: 75.8% 10-fold dosing: 80.5% |

| J. Bullock et al. (USA, 2006) [39] | UBA, single center | pICU | Analysis of medication error reports in a Medication Event Reporting System pre- and post-implementation | Standard concentrations for 27 intravenous medications Intensive education: One-on-one coaching, mentoring | Incorrect dosing and concentration | The error rate of incorrect dosage decreased from 26/50 incorrect orders to 7/28 incorrect orders. (p < 0.05) The error rate of incorrect concentration decreased from 6/26 orders with incorrect dosage to no incidents in 7 orders with incorrect dosage. (p < 0.05) | Dosing: 51.9% (p < 0.05) Concentration: 100% (p < 0.05) |

| S. Arenas-Lopez et al. (UK, 2017) [21] | UBA, single center | pICU | Analysis of morphine-related medication errors from the hospital incident reporting system over 8 years |

| Morphine-related errors | 126 errors related to morphine infusions were recorded. Drug errors related to morphine decreased from 45% to 2.2%. There were 24 prescription errors connected with standard concentrations in a total of 36 prescription errors. (22 of 24 did not result in patient harm.) Administration errors (e.g., programming errors or selecting the wrong syringe) occurred twice as frequently in standard concentrations (n = 46) compared to variable concentrations (n = 18, p = 0.025). | Morphine: 95.1% Administration RR: 2.0 → RRI 100% (p = 0.025) |

| A. Rashed et al. (UK, 2019) [23] | UBA, single center | Pediatric hospital | Analysis of morphine infusion (nurse- and patient-controlled analgesia) incident reports from the electronic reporting system (January 2013–December 2015) |

| Risk of medication errors | 54 failures occurred, 34 of them in the old system and 20 of them in the new system. Relative Risk Reduction is reported as 41.2% (p = 0.115). Details of error types are provided by the study. | Overall: 41.2% (p = 0.115) |

| M. Howlett et al. (Ireland, 2020) [38] | UBA, single center | pICU | Analysis of medication orders by a clinical pharmacist over 24 weeks across four time periods (Epochs 1–4) | Stepwise implementation: 1. Smart pumps with a drug library and standard concentrations for 4 weight bands 2. Electronic prescribing | Prescribing errors in medication orders Epoch 1: Before implementation Epoch 2: Directly after implementing SC and smart pumps Epoch 3: After implementing electronic prescribing Epoch 4: 1-year post-implementation. | 3356 medication orders were reviewed by a pharmacist. 684 were infusion orders which caused 98 infusion-related prescribing errors: Epoch 1: 29.0% Epoch 2: 14.6% (p < 0.001) Epoch 3: 4.7% (p > 0.05) Epoch 4: 8.4% (p = 0.32) Paper generated error rate: Epoch 1: 78% Epoch 2: 97% Error rate in infusion: Epoch 1: 29% Epoch 4: 8.4% | Prescribing Epoch 1 → 2: 49.7% (p < 0.001) Epoch 1 → 4: 71.0% Paper-generated risk RR 1.24 → RRI 24.5% |

3. Results

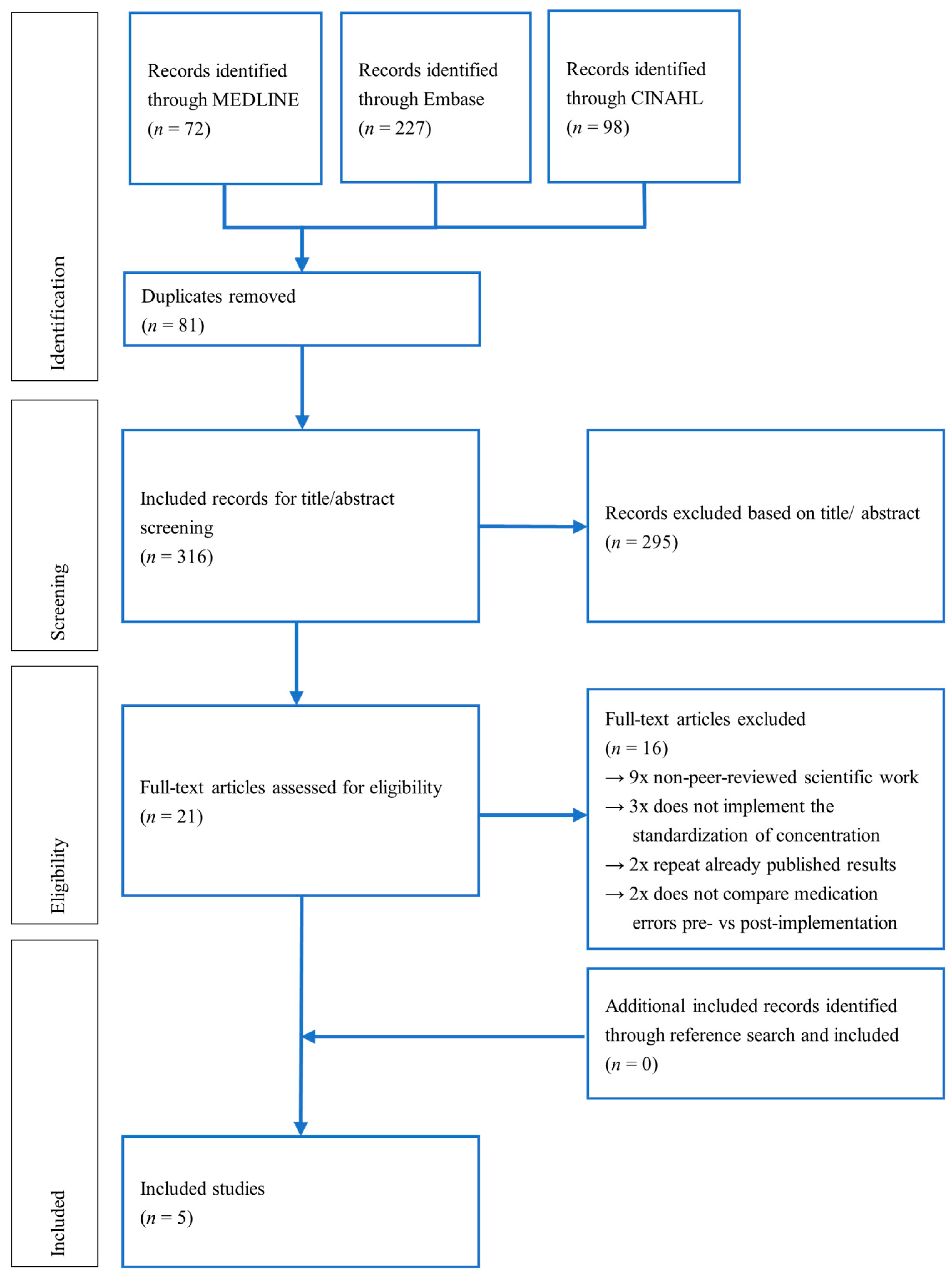

3.1. Study Selection

3.2. Study Characteristics

3.3. Risk of Bias Within Studies

3.4. Synthesis of Results

3.5. Risk of Bias Across Studies

3.6. Additional Analyses

4. Discussion

4.1. Summary of Evidence

4.2. Strength and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ADE | adverse drug event |

| CBA | controlled before-after study |

| CCT | controlled clinical trial |

| EPOC | Cochrane Effective Practice and Organisation of Care |

| FMEA | Failure Mode and Effects Analysis |

| ITS | interrupted time series |

| IV | intravenous |

| ME | medication error |

| N/PCA | nurse- and patient-controlled analgesia |

| NICU | neonatal intensive care unit |

| NPSA | National Patient Safety Agency |

| pICU | pediatric intensive care unit |

| PRISMA | Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses |

| RCT | randomized controlled trial |

| ROBINS-I tool | Risk Of Bias In Non-randomized Studies of Interventions |

| RRI | relative risk increase |

| RRR | relative risk reduction |

| SC | standard concentration |

References

- Alghamdi, A.A.; Keers, R.N.; Sutherland, A.; Ashcroft, D.M. Prevalence and Nature of Medication Errors and Preventable Adverse Drug Events in Paediatric and Neonatal Intensive Care Settings: A Systematic Review. Drug Saf. 2019, 42, 1423–1436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ameer, A.; Dhillon, S.; Peters, M.J.; Ghaleb, M. Systematic Literature Review of Hospital Medication Administration Errors in Children. Integr. Pharm. Res. Pract. 2015, 4, 153–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaushal, R.; Bates, D.W.; Landrigan, C.; Mckenna, K.J.; Clapp, M.D.; Federico, R.F.; Goldmann, D.A. Medication Errors and Adverse Drug Events in Pediatric Inpatients. JAMA 2001, 285, 2114–2120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basil, H.J.; Premakumar, C.M.; Mhd Ali, A.; Mohd Tahir, N.A.; Seman, Z.; Voo, J.Y.H.; Ishak, S.; Shah, M.N. Prevalence and Factors Associated with Medication Administration Errors in the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit: A Multicentre, Nationwide Direct Observational Study. J. Adv. Nurs. 2025, 81, 820–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutherland, A.; Phipps, D.L.; Tomlin, S.; Ashcroft, D.M. Mapping the Prevalence and Nature of Drug Related Problems among Hospitalised Children in the United Kingdom: A Systematic Review. BMC Pediatr. 2019, 19, 486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicholas, P.K.; Agius, C.R. Toward Safer IV Medication Administration: The Narrow Safety Margins of Many IV Medications Make This Route Particularly Dangerous. Am. J. Nurs. 2005, 105, 25–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDowell, S.E.; Mt-Isa, S.; Ashby, D.; Ferner, R.E. Where Errors Occur in the Preparation and Administration of Intravenous Medicines: A Systematic Review and Bayesian Analysis. Qual. Saf. Health Care 2010, 19, 341–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aguado-Lorenzo, V.; Weeks, K.; Tunstell, P.; Turnock, K.; Watts, T.; Arenas-Lopez, S. Accuracy of the Concentration of Morphine Infusions Prepared for Patients in a Neonatal Intensive Care Unit. Arch. Dis. Child. 2013, 98, 975–979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santesteban, E.; Arenas, S.; Campino, A. Medication Errors in Neonatal Care: A Systematic Review of Types of Errors and Effectiveness of Preventive Strategies. J. Neonatal Nurs. 2015, 21, 200–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daya, M.A.; Alsohaimi, A.; Angadi, U. P39 Impact of Conventional Weight-Based Concentrations of Infusions on Patient Safety in Picu. BMJ Paediatr. Open 2024, 8 (Suppl. S3), A21–A39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koeck, J.A.; Young, N.J.; Kontny, U.; Orlikowsky, T.; Bassler, D.; Eisert, A. Interventions to Reduce Pediatric Prescribing Errors in Professional Healthcare Settings: A Systematic Review of the Last Decade. Paediatr. Drugs 2021, 23, 223–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koeck, J.A.; Young, N.J.; Kontny, U.; Orlikowsky, T.; Bassler, D.; Eisert, A. Interventions to Reduce Medication Dispensing, Administration, and Monitoring Errors in Pediatric Professional Healthcare Settings: A Systematic Review. Front. Pediatr. 2021, 9, 633064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keers, R.N.; Williams, S.D.; Cooke, J.; Ashcroft, D.M. Causes of Medication Administration Errors in Hospitals: A Systematic Review of Quantitative and Qualitative Evidence. Drug Saf. 2013, 36, 1045–1067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aghighi, N.; Aryankhesal, A.; Raeissi, P. Factors Affecting the Recurrence of Medical Errors in Hospitals and the Preventive Strategies: A Scoping Review. J. Med. Ethics Hist. Med. 2022, 15, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Hobe, S.; Schoberer, M.; Orlikowsky, T.; Müller, J.; Kusch, N.; Eisert, A. Impact of a Bundle of Interventions on the Spectrum of Parenteral Drug Preparation Errors in a Neonatal and Pediatric Intensive Care Unit. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 6053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaufmann, J.; Wolf, A.R.; Becke, K.; Laschat, M.; Wappler, F.; Engelhardt, T. Drug Safety in Paediatric Anaesthesia. Br. J. Anaesth. 2017, 118, 670–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jung, B.; Couldry, R.; Wilkinson, S.; Grauer, D. Implementation of Standardized Dosing Units for i.v. Medications. Am. J. Health-Syst. Pharm. 2014, 71, 2153–2158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Errico, S.; Zanon, M.; Radaelli, D.; Padovano, M.; Santurro, A.; Scopetti, M.; Frati, P.; Fineschi, V. Medication Errors in Pediatrics: Proposals to Improve the Quality and Safety of Care Through Clinical Risk Management. Front. Med. 2022, 8, 814100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campino, A.; Santesteban, E.; Pascual, P.; Sordo, B.; Arranz, C.; Unceta, M.; Lopez-De-Heredia, I. Strategies Implementation to Reduce Medicine Preparation Error Rate in Neonatal Intensive Care Units. Eur. J. Pediatr. 2016, 175, 755–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, C.A.; Siu, A.; Meyers, R.; Lee, B.H.; Cash, J. Standard Dose Development for Medications Commonly Used in the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit. J. Pediatr. Pharmacol. Ther. 2014, 19, 118–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arenas-López, S.; Stanley, I.M.; Tunstell, P.; Aguado-Lorenzo, V.; Philip, J.; Perkins, J.; Durward, A.; Calleja-Hernández, M.A.; Tibby, S.M. Safe Implementation of Standard Concentration Infusions in Paediatric Intensive Care. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 2017, 69, 529–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsen, G.Y.; Parker, H.B.; Cash, J.; O’Connell, M.; Grant, M.J.C. Standard Drug Concentrations and Smart-Pump Technology Reduce Continuous-Medication-Infusion Errors in Pediatric Patients. Pediatrics 2005, 116, e21–e25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashed, A.N.; Whittlesea, C.; Davies, C.; Forbes, B.; Tomlin, S. Standardised Concentrations of Morphine Infusions for Nurse/Patient-Controlled Analgesia Use in Children. BMC Anesthesiol. 2019, 19, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roman, N. Innovative Solutions: Standardized Concentrations Facilitate the Use of Continuous Infusions for Pediatric Intensive Care Unit Nurses at a Community Hospital. Dimens. Crit. Care Nurs. 2005, 24, 275–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medscape. Avoid Preparing Infusions Using the Rule of 6 or Broselow Tape. 2005. Available online: https://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/501053?form=fpf (accessed on 2 May 2025).

- Rich, D.S. New JCAHO Medication Management Standards for 2004. Am. J. Health Syst. Pharm. 2004, 61, 1349–1358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eiland, L.S.; Benner, K.; Gumpper, K.F.; Heigham, M.K.; Meyers, R.; Pham, K.; Potts, A.L. ASHP–PPAG Guidelines for Providing Pediatric Pharmacy Services in Hospitals and Health Systems. J. Pediatr. Pharmacol. Ther. 2018, 23, 177–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ASHP. Standardize 4 Safety Initiative. Available online: https://www.ashp.org/pharmacy-practice/standardize-4-safety-initiative?loginreturnUrl=SSOCheckOnly (accessed on 28 September 2025).

- Institute for Safe Medication Practices (ISMP). Targeted Medication Safety Best Practices for Hospitals. 2024. Available online: https://home.ecri.org/blogs/ismp-resources/targeted-medication-safety-best-practices-for-hospitals (accessed on 9 August 2025).

- Neonatal & Paediatric Pharmacy Group; British Association of Perinatal Medicine; Paediatric Critical Care Society; Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health. Standardising Intravenous Infusion Concentrations for Neonates and Children in the UK—Framework. 2024. Available online: https://www.rcpch.ac.uk/resources/standardising-intravenous-infusion-concentrations-neonates-children-uk-framework (accessed on 9 August 2025).

- The Swedish National Formulary for Children. ePed. Available online: https://eped.se/about-eped/ (accessed on 9 August 2025).

- Garnemark, C.A.; Nydert, P.; Lindemalm, S. The Swedish National Formulary for Children ePed. Comment on Shaniv et al. A Callout for International Collaboration. Reply to Giger, E.V.; Tilen, R. Comment on “Shaniv et al. Neonatal Drug Formularies—A Global Scope. Children 2023, 10, 848”. Children 2023, 10, 1803. Children 2024, 11, 1339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, M.N.R.; Mosel, C.; Grzeskowiak, L.E. Interventions to Reduce Medication Errors in Neonatal Care: A Systematic Review. Ther. Adv. Drug Saf. 2018, 9, 123–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alharthi, A.; Alshagrawi, S. The Impact of Standardization of Intravenous Medication on Patient Safety and Quality of Healthcare: A Systematic Review. Open Public Health J. 2024, 17, e18749445335795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liberati, A.; Altman, D.G.; Tetzlaff, J.; Mulrow, C.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Ioannidis, J.P.A.; Clarke, M.; Devereaux, P.J.; Kleijnen, J.; Moher, D. The PRISMA Statement for Reporting Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses of Studies That Evaluate Health Care Interventions: Explanation and Elaboration. PLoS Med. 2009, 6, e1000100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 Statement: An Updated Guideline for Reporting Systematic Reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Effective Practice and Organization of Care What Study Designs Should Be Included in an EPOC Review and What Should They Be Called? Available online: https://epoc.cochrane.org/sites/epoc.cochrane.org/files/uploads/EPOC%20Study%20Designs%20About.pdf (accessed on 23 August 2025).

- Howlett, M.M.; Butler, E.; Lavelle, K.M.; Cleary, B.J.; Breatnach, C.V. The Impact of Technology on Prescribing Errors in Pediatric Intensive Care: A Before and After Study. Appl. Clin. Inform. 2020, 11, 323–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bullock, J.; Jordan, D.; Gawlinski, A.; Henneman, E.A. Standardizing IV Infusion Medication Concentrations to Reduce Variability in Medication Errors. Crit. Care Nurs. Clin. N. Am. 2006, 18, 515–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orwin, R.G. Evaluating Coding Decisions. In The Handbook of Research Synthesis; Cooper, H., Hedges, L.V., Eds.; Russell Sage Foundation: New York, NY, USA, 1994; pp. 139–203. [Google Scholar]

- Sterne, J.A.; Hernán, M.A.; Reeves, B.C.; Savović, J.; Berkman, N.D.; Viswanathan, M.; Henry, D.; Altman, D.G.; Ansari, M.T.; Boutron, I.; et al. ROBINS-I: A Tool for Assessing Risk of Bias in Non-Randomised Studies of Interventions. BMJ 2016, 355, i4919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsen, A.B.; Haugbølle, L.S. The Impact of an Automated Dose-Dispensing Scheme on User Compliance, Medication Understanding, and Medication Stockpiles. Res. Social. Adm. Pharm. 2007, 3, 265–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, A.; Sommo, P.; Mocerine, T.; Lesar, T. A Standardized Approach to Pediatric Parenteral Medication Delivery. Hosp. Pharm. 2004, 39, 433–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilmas, E.; Sowan, A.; Gaffoor, M.; Vaidya, V. Implementation and Evaluation of a Comprehensive System to Deliver Pediatric Continuous Infusion Medications with Standardized Concentrations. Am. J. Health Syst. Pharm. 2010, 67, 58–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irwin, D.; Vaillancourt, R.; Dalgleish, D.; Thomas, M.; Grenier, S.; Wong, E.; Wright, M.; Sears, M.; Doherty, D.; Gaboury, I. Standard Concentrations of High-Alert Drug Infusions across Paediatric Acute Care. Paediatr. Child Health 2008, 13, 371–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polischuk, E.; Vetterly, C.G.; Crowley, K.L.; Thompson, A.; Goff, J.; Nguyen-Ha, P.-T.; Modery, C. Implementation of a Standardized Process for Ordering and Dispensing of High-Alert Emergency Medication Infusions. J. Pediatr. Pharmacol. Ther. 2012, 17, 166–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apkon, M.; Leonard, J.; Probst, L.; DeLizio, L.; Vitale, R. Design of a Safer Approach to Intravenous Drug Infusions: Failure Mode Effects Analysis. Qual. Saf. Health Care 2004, 13, 265–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sowan, A.K.; Vaidya, V.U.; Soeken, K.L.; Hilmas, E. Computerized Orders with Standardized Concentrations Decrease Dispensing Errors of Continuous Infusion Medications for Pediatrics. J. Pediatr. Pharmacol. Ther. 2010, 15, 189–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perkins, J.; Aguado-Lorenzo, V.; Arenas-Lopez, S. Standard Concentration Infusions in Paediatric Intensive Care: The Clinical Approach. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 2017, 69, 537–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barreto, H.A.G.; Sestren, B.; Boergen-Lacerda, R.; Soares, L.C. da C. Standard Concentration Infusions of Inotropic and Vasoactive Drugs in Paediatric Intensive Care: A Strategy for Patient Safety. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 2019, 71, 826–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulmer, J.; Drinnan, M.; Smith, J. Technical Response to the Neonatal and Paediatric Group’s Proposal to standardise Intravenous Concentrations for children in the UK. Arch. Dis. Child. 2023, 108, 314–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cree, M.; Health, Q. Adherence to Standard Medication Infusion Concentrations and Its Impact on Paediatric Intensive Care Patient Outcomes. Aust. Crit. Care 2018, 31, 213–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hedlund, N.; Beer, I.; Hoppe-Tichy, T.; Trbovich, P. Systematic Evidence Review of Rates and Burden of Harm of Intravenous Admixture Drug Preparation Errors in Healthcare Settings. BMJ Open 2017, 7, e015912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niemi, K.; Geary, S.; Larrabee, M.; Brown, K.R. Standardized Vasoactive Medications: A Unified System for Every Patient, Everywhere. Hosp. Pharm. 2005, 40, 984–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swanson, A. Nix the Six: Raise the Bar on Medication Delivery. Newborn Infant. Nurs. Rev. 2006, 6, 230–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, K.L.; Wright, D.; Laxton, B.; Miller, K.M.; Meyers, J.; Englebright, J. Implementation of Standardized Pediatric i.v. Medication Concentrations. Am. J. Health Syst. Pharm. 2014, 71, 1500–1508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mulvihill, C.; McDonald, D. Standardized Neonatal Continuous Infusion Concentrations: A Quality Improvement Initiative. Am. J. Health Syst. Pharm. 2023, 80, 61–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whalen, K.; Lynch, E.; Moawad, I.; John, T.; Lozowski, D.; Cummings, B.M. Transition to a New Electronic Health Record and Pediatric Medication Safety: Lessons Learned in Pediatrics within a Large Academic Health System. J. Am. Med. Inform. Assoc. 2018, 25, 848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Study Characteristic | Number of Included Studies |

|---|---|

| Study design | |

| RCT, CCT, CBA, ITS | 0 |

| UBA | 5 |

| Authorship | |

| International | 1 |

| Same country | 1 |

| Same city | 3 |

| Setting | |

| Pediatric hospital | 2 |

| pICU | 3 |

| Country | |

| Ireland | 1 |

| UK | 2 |

| USA | 2 |

| Bullock et al. [39] | Rashed et al. [23] | Larsen et al. [42] | Howlett et al. [38] | Arenas-Lopez et al. [21] | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bias due to confounding | Serious risk | Critical risk | Critical risk | Critical risk | Critical risk |

| Bias in selection of participants | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk |

| Bias in classification of interventions | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk |

| Bias due to deviations from intended interventions | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk |

| Bias due to missing data | Moderate risk | Low risk | Moderate risk | Low risk | Low risk |

| Bias in measurement of outcomes | Low risk | Moderate risk | Moderate risk | Low risk | Low risk |

| Bias in selection of reported results | Moderate risk | Moderate risk | Moderate risk | Moderate risk | Moderate risk |

| Overall bias | Serious risk | Critical risk | Critical risk | Critical risk | Critical risk |

| Additional Factors | Description and Effect | Mentioned in |

|---|---|---|

| Implementation Team | A multidisciplinary team, including physicians, nurses, pharmacists and medical informaticians in planning and implementation | Arenas-Lopez et al. [21] |

| Workflow | Reduction in bedside calculations, when combining with smart pumps and electronic prescribing systems | Arenas-Lopez et al. [21], Larsen et al. [22] |

| Central/batch preparation to reduce deviations in concentrations and microbial contamination risk | Arenas-Lopez et al. [21], Rashed et al. [23] | |

| Measured reduction in medication process time | Rashed et al. [23] | |

| Fluid Volume Management | With well-chosen SC, in most patients, fluid overload must not be expected | Larsen et al. [22] |

| Staff Education Methods | Initial and ongoing to guarantee a safe implementation process. (e.g., lectures, mentoring, train-the-trainer, electronic reminders) | Arenas-Lopez et al. [21], Bullock et al. [39], Larsen et al. [22], Howlett et al. [38] |

| Staff Satisfaction | Survey resulted in a perception of improved safety and time savings | Rashed et al. [23] |

| Cost Considerations | Cost-neutral implementation costs to a potential reduction in costs | Bullock et al. [39], Larsen et al. [22] |

| Advantages | Challenges | |

|---|---|---|

| Medication Safety | ||

| Preparation Accuracy |

| |

| Workflow Efficiency |

| |

| Technology Integration | ||

| Risk Management | ||

| Staff Perspective | ||

| Cost and Resources |

|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wende, L.; Schoberer, M.; Kaune, A.; Kreutzer, K.B.; Orlikowsky, T.; Christiansen, N.; Nydert, P.; Schubert, S.; Eisert, A. The Effect of Standard Concentration Infusions on Medication Errors in Neonatal and Pediatric Healthcare Settings: A Systematic Review. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 7965. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14227965

Wende L, Schoberer M, Kaune A, Kreutzer KB, Orlikowsky T, Christiansen N, Nydert P, Schubert S, Eisert A. The Effect of Standard Concentration Infusions on Medication Errors in Neonatal and Pediatric Healthcare Settings: A Systematic Review. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(22):7965. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14227965

Chicago/Turabian StyleWende, Lisa, Mark Schoberer, Almuth Kaune, Karen B. Kreutzer, Thorsten Orlikowsky, Nanna Christiansen, Per Nydert, Sebastian Schubert, and Albrecht Eisert. 2025. "The Effect of Standard Concentration Infusions on Medication Errors in Neonatal and Pediatric Healthcare Settings: A Systematic Review" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 22: 7965. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14227965

APA StyleWende, L., Schoberer, M., Kaune, A., Kreutzer, K. B., Orlikowsky, T., Christiansen, N., Nydert, P., Schubert, S., & Eisert, A. (2025). The Effect of Standard Concentration Infusions on Medication Errors in Neonatal and Pediatric Healthcare Settings: A Systematic Review. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(22), 7965. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14227965