Relationship Between Retinal Vascular Measurements and Anthropometric Indices in Patients Diagnosed with Persistent COVID-19

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

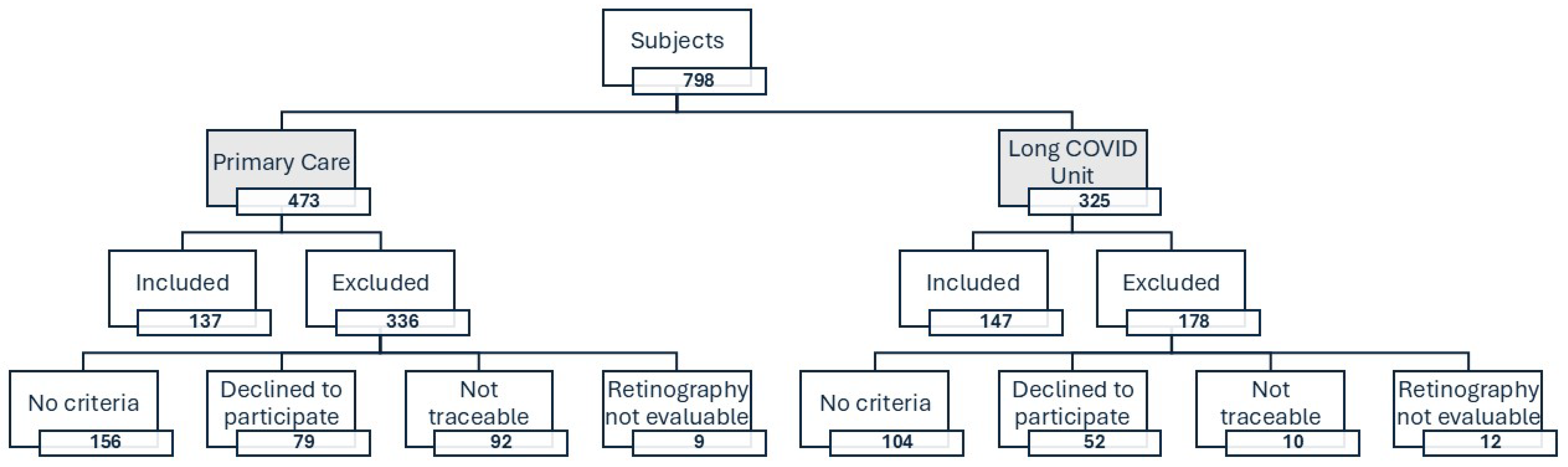

2.1. Study Design and Setting

2.2. Study Population

2.3. Variables and Measurement Instruments

2.3.1. Sociodemographic Variables and Cardiovascular Risk Factors

2.3.2. Lifestyle Variables

2.3.3. Determination of Biomarkers of Endothelial Damage

2.3.4. Variables Related to Persistent COVID

2.3.5. Anthropometric Variables

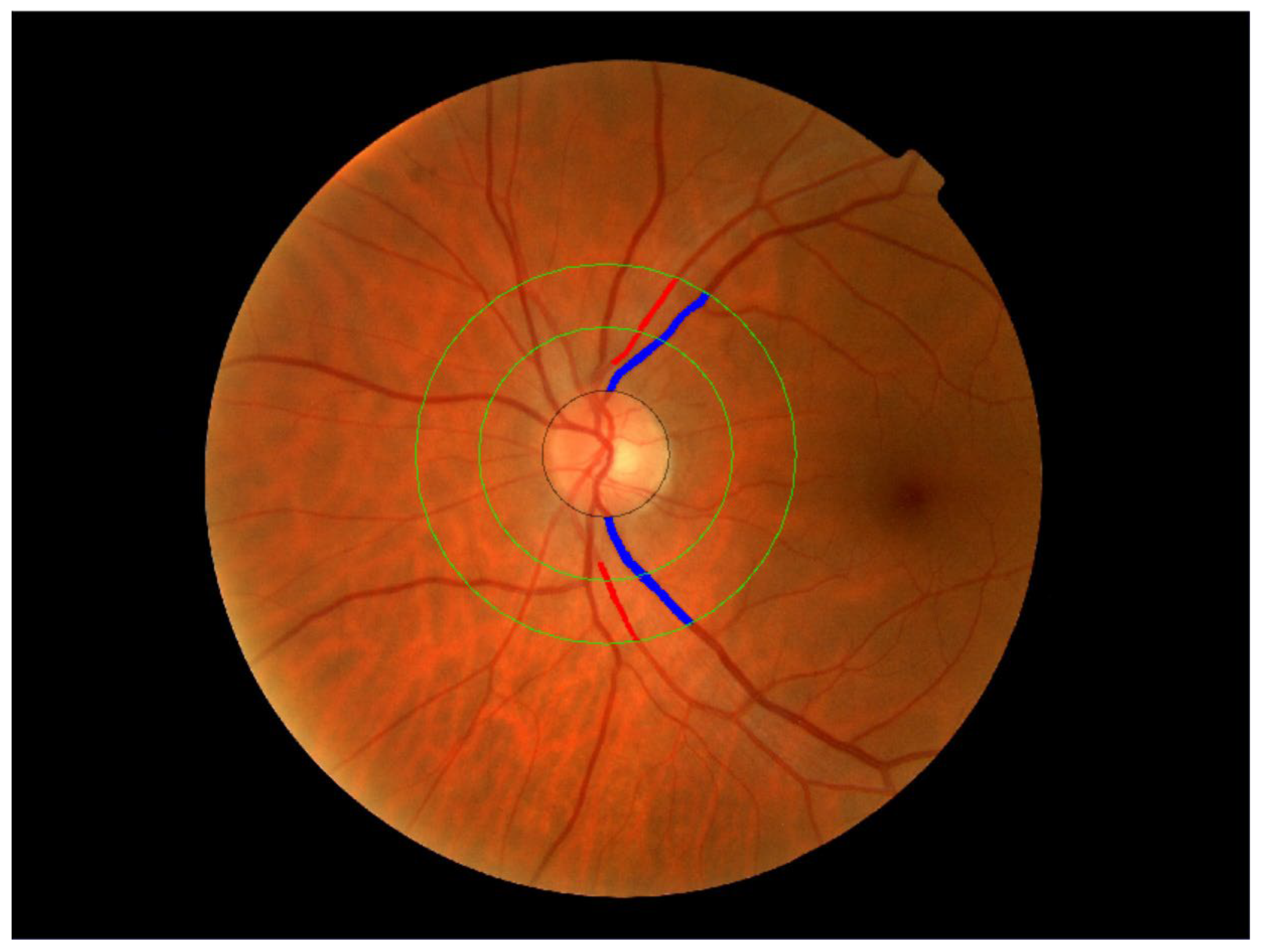

2.3.6. Retinal Vessel Assessment

2.4. Statistical Analysis

2.5. Ethical Considerations

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of the Study Population

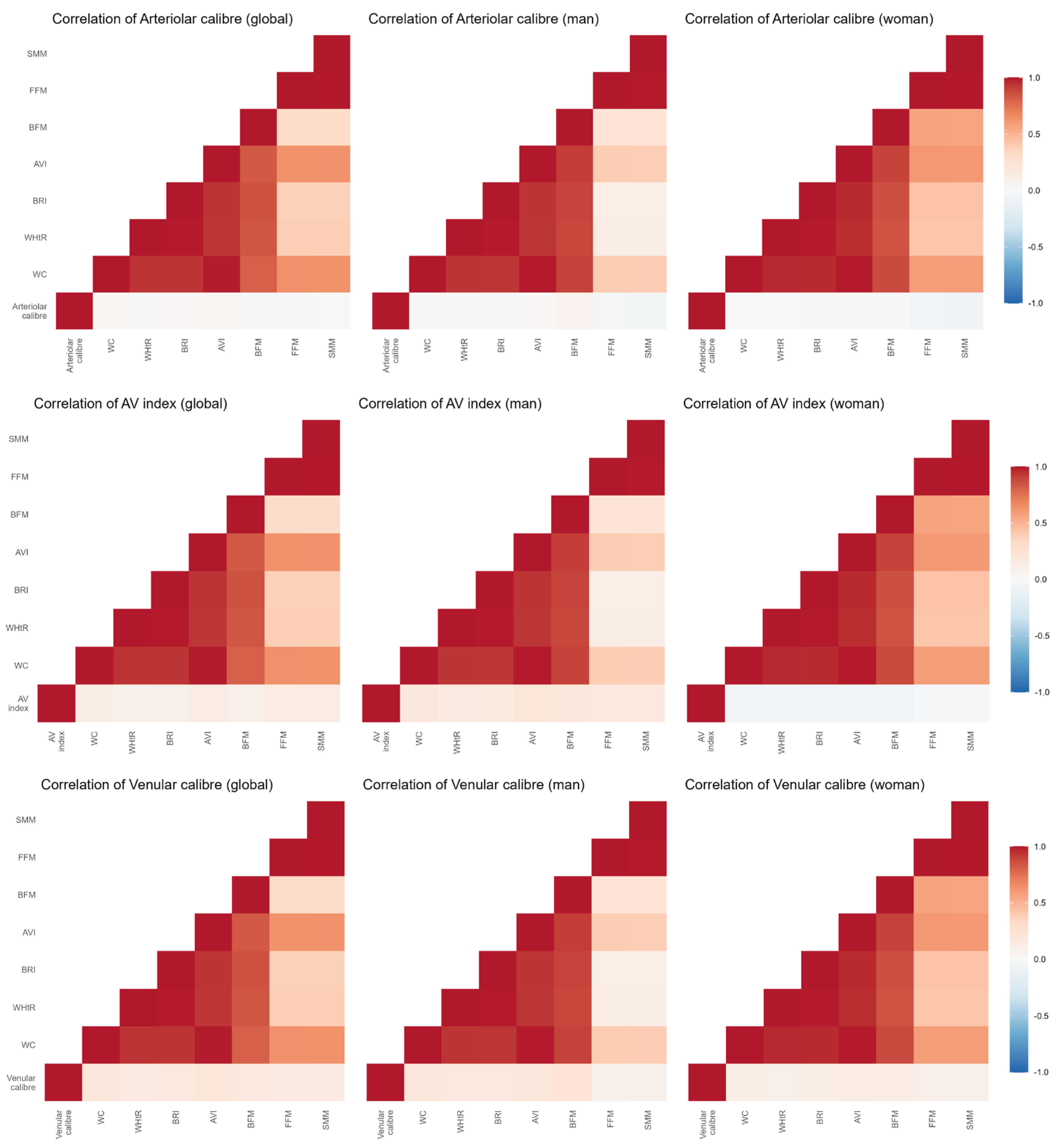

3.2. Association Between Anthropometric Values and Retinal Blood Vessels

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BMI | Body mass index |

| WHtR | Waist height ratio |

| BRI | Body roundness index |

| AVI | Abdominal volume index |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

| SBP | Systolic blood pressure |

| DBP | Diastolic blood pressure |

| SEEDO | Spanish Society for the Study of Obesity |

| BFM | Body fat mass |

| SMM | Skeletal muscle mass |

| FFM | Fat-free mass |

| AV Index | Arteriole to venule ratio |

References

- Soriano, J.B.; Murthy, S.; Marshall, J.C.; Relan, P.; Diaz, J.V. A Clinical Case Definition of Post-COVID-19 Condition by a Delphi Consensus. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2022, 22, e102–e107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karakasis, P.; Nasoufidou, A.; Sagris, M.; Fragakis, N.; Tsioufis, K. Vascular Alterations Following COVID-19 Infection: A Comprehensive Literature Review. Life 2024, 14, 545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, T.Y.; Knudtson, M.D.; Klein, R.; Klein, B.E.K.; Meuer, S.M.; Hubbard, L.D. Computer-Assisted Measurement of Retinal Vessel Diameters in the Beaver Dam Eye Study: Methodology, Correlation between Eyes, and Effect of Refractive Errors. Ophthalmology 2004, 111, 1183–1190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Y.; Dong, M.; Wen, S.; Yuan, X.; Zhou, L. Retinal Microcirculation: A Window into Systemic Circulation and Metabolic Disease. Exp. Eye Res. 2024, 242, 109885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Sánchez, L.; Gómez-Sánchez, M.; Patino-Alonso, C.; Recio-Rodríguez, J.I.; González-Sánchez, J.; Agudo-Conde, C.; Maderuelo-Fernández, J.A.; Rodríguez-Sánchez, E.; García-Ortiz, L.; Gómez-Marcos, M.A.; et al. Retinal Blood Vessel Calibre and Vascular Ageing in a General Spanish Population: A EVA Study. Eur. J. Clin. Investig. 2022, 52, e13684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.J.V.; Goh, Y.Q.; Rojas-Carabali, W.; Cifuentes-González, C.; Cheung, C.Y.; Arora, A.; de-la-Torre, A.; Gupta, V.; Agrawal, R. Association between Retinal Vessels Caliber and Systemic Health: A Comprehensive Review. Surv. Ophthalmol. 2024, 70, 184–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gates, P.E.; Strain, W.D.; Shore, A.C. Human Endothelial Function and Microvascular Ageing. Exp. Physiol. 2009, 94, 311–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, S.R.; Bellary, S.; Karimzad, S.; Gherghel, D. Overweight Status Is Associated with Extensive Signs of Microvascular Dysfunction and Cardiovascular Risk. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 32282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Köchli, S.; Endes, K.; Infanger, D.; Zahner, L.; Hanssen, H. Obesity, Blood Pressure, and Retinal Vessels: A Meta-Analysis. Pediatrics 2018, 141, e20174090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gong, W.; Hu, Y.; Niu, Y.; Wang, D.; Wang, Y.; Li, Y.; Holden, B.A.; He, M. Effects of Longitudinal Body Mass Index Variability on Microvasculature over 5 Years in Adult Chinese. Obesity 2016, 24, 743–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tapp, R.J.; Owen, C.G.; Barman, S.A.; Welikala, R.A.; Foster, P.J.; Whincup, P.H.; Strachan, D.P.; Rudnicka, A.R. Retinal Vascular Tortuosity and Diameter Associations with Adiposity and Components of Body Composition. Obesity 2020, 28, 1750–1760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sweatt, K.; Garvey, W.T.; Martins, C. Strengths and Limitations of BMI in the Diagnosis of Obesity: What Is the Path Forward? Curr. Obes. Rep. 2024, 13, 584–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, E.L.; Parkinson, J.R.; Frost, G.S.; Goldstone, A.P.; Doré, C.J.; McCarthy, J.P.; Collins, A.L.; Fitzpatrick, J.A.; Durighel, G.; Taylor-Robinson, S.D.; et al. The Missing Risk: MRI and MRS Phenotyping of Abdominal Adiposity and Ectopic Fat. Obesity 2012, 20, 76–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paniagua, L.; Lohsoonthorn, V.; Lertmaharit, S.; Jiamjarasrangsi, W.; Williams, M.A. Comparison of Waist Circumference, Body Mass Index, Percent Body Fat and Other Measure of Adiposity in Identifying Cardiovascular Disease Risks among Thai Adults. Obes. Res. Clin. Pract. 2008, 2, 215–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza, A.C.d.A.H.; Rosenthal, M.H.; Moura, F.A.; Divakaran, S.; Osborne, M.T.; Hainer, J.; Dorbala, S.; Blankstein, R.; Di Carli, M.F.; Taqueti, V.R. Body Composition, Coronary Microvascular Dysfunction, and Future Risk of Cardiovascular Events Including Heart Failure. JACC Cardiovasc. Imaging 2024, 17, 179–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Sánchez, L.; Tamayo-Morales, O.; Suárez-Moreno, N.; Bermejo-Martín, J.F.; Domínguez-Martín, A.; Martín-Oterino, J.A.; Martín-González, J.I.; González-Calle, D.; García-García, Á.; Lugones-Sánchez, C.; et al. Relationship between the Structure, Function and Endothelial Damage, and Vascular Ageing and the Biopsychological Situation in Adults Diagnosed with Persistent COVID (BioICOPER Study). A Research Protocol of a Cross-Sectional Study. Front. Physiol 2023, 14, 1236430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, B.; Mancia, G.; Spiering, W.; Agabiti Rosei, E.; Azizi, M.; Burnier, M.; Clement, D.; Coca, A.; De Simone, G.; Dominiczak, A.; et al. 2018 Practice Guidelines for the Management of Arterial Hypertension of the European Society of Cardiology and the European Society of Hypertension. Blood Press 2018, 27, 314–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. Global Physical Activity Questionnaire (GPAQ) Analysis Guide; Geneva World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2012; pp. 1–22.

- Karelis, A.D.; Aubertin-Leheudre, M.; Duval, C.; Chamberland, G. Validation of a Portable Bioelectrical Impedance Analyzer for the Assessment of Body Composition. Appl. Physiol. Nutr. Metab. 2013, 38, 27–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubio Hererra, M.A.; Salas-Salvadó, J.; Barbany, M.; Moreno, B.; Aranceta, J.; Bellido, D.; Blay, V.; Carraro, R.; Formiguera, X.; Foz, M.; et al. Consenso SEEDO 2007 Para La Evaluación Del Sobrepeso y La Obesidad y El Establecimiento de Criterios de Intervención Terapéutica. Rev. Esp. De Obes. 2007, 5, 135–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, D.M.; Bredlau, C.; Bosy-Westphal, A.; Mueller, M.; Shen, W.; Gallagher, D.; Maeda, Y.; McDougall, A.; Peterson, C.M.; Ravussin, E.; et al. Relationships between Body Roundness with Body Fat and Visceral Adipose Tissue Emerging from a New Geometrical Model. Obesity 2013, 21, 2264–2271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guerrero-Romero, F.; Rodríguez-Morán, M. Abdominal Volume Index. An Anthropometry-Based Index for Estimation of Obesity Is Strongly Related to Impaired Glucose Tolerance and Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Arch. Med. Res. 2003, 34, 428–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Ortiz, L.; Recio-Rodríguez, J.I.; Parra-Sanchez, J.; Elena, L.J.G.; Patino-Alonso, M.C.; Agudo-Conde, C.; Rodríguez-Sánchez, E.; Gómez-Marcos, M.A. A New Tool to Assess Retinal Vessel Caliber. Reliability and Validity of Measures and Their Relationship with Cardiovascular Risk. J. Hypertens. 2012, 30, 770–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, P.A.; Taylor, R.; Minor, B.L.; Elliott, V.; Fernandez, M.; O’Neal, L.; McLeod, L.; Delacqua, G.; Delacqua, F.; Kirby, J.; et al. The REDCap Consortium: Building an International Community of Software Platform Partners. J. Biomed. Inform. 2019, 95, 103208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Medical Association. World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki: Ethical Principles for Medical Research Involving Human Subjects. JAMA 2013, 310, 2191–2194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boillot, A.; Zoungas, S.; Mitchell, P.; Klein, R.; Klein, B.; Ikram, M.K.; Klaver, C.; Wang, J.J.; Gopinath, B.; Tai, E.S.; et al. Obesity and the Microvasculature: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e52708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owen, C.G.; Rudnicka, A.R.; Welikala, R.A.; Fraz, M.M.; Barman, S.A.; Luben, R.; Hayat, S.A.; Khaw, K.T.; Strachan, D.P.; Whincup, P.H.; et al. Retinal Vasculometry Associations with Cardiometabolic Risk Factors in the European Prospective Investigation of Cancer—Norfolk Study. Ophthalmology 2019, 126, 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tchernof, A.; Després, J.P. Pathophysiology of Human Visceral Obesity: An Update. Physiol. Rev. 2013, 93, 359–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, M.; Lovern, C.; Lycett, K.; He, M.; Wake, M.; Wong, T.Y.; Burgner, D.P. The Association between Markers of Inflammation and Retinal Microvascular Parameters: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Atherosclerosis 2021, 336, 12–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuchler, T.; Günthner, R.; Ribeiro, A.; Hausinger, R.; Streese, L.; Wöhnl, A.; Kesseler, V.; Negele, J.; Assali, T.; Carbajo-Lozoya, J.; et al. Persistent Endothelial Dysfunction in Post-COVID-19 Syndrome and Its Associations with Symptom Severity and Chronic Inflammation. Angiogenesis 2023, 26, 547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, C.; Wang, J.J.; Mackey, D.A.; Wong, T.Y. Retinal Vascular Caliber: Systemic, Environmental, and Genetic Associations. Surv. Ophthalmol. 2009, 54, 74–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández, M.S.; Fernández-Alfonso, F.; Somoza, B.; Tsvetkov, D.; Kuczmanski, A.; Dashwood, M.; Gil-Ortega, M. Role of Perivascular Adipose Tissue in Health and Disease. Compr. Physiol. 2018, 8, 23–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karimzad, S.; Shokr, H.; Bellary, S.; Singhal, R.; Gherghel, D. The Effect of Bariatric Surgery on Microvascular Structure and Function, Peripheral Pressure Waveform and General Cardiovascular Risk: A Longitudinal Study. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 7379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kurniawan, E.D.; Cheung, C.Y.; Tay, W.T.; Mitchell, P.; Saw, S.M.; Wong, T.Y.; Cheung, N. The Relationship between Changes in Body Mass Index and Retinal Vascular Caliber in Children. J. Pediatr. 2014, 165, 1166–1171.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shankar, A.; Sabanayagam, C.; Klein, B.E.K.; Klein, R. Retinal Microvascular Changes and the Risk of Developing Obesity: Population-Based Cohort Study. Microcirculation 2011, 18, 655–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renna, N.F.; De Las Heras, N.; Miatello, R.M. Pathophysiology of Vascular Remodeling in Hypertension. Int. J. Hypertens. 2013, 2013, 808353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanssen, H.; Siegrist, M.; Neidig, M.; Renner, A.; Birzele, P.; Siclovan, A.; Blume, K.; Lammel, C.; Haller, B.; Schmidt-Trucksäss, A.; et al. Retinal Vessel Diameter, Obesity and Metabolic Risk Factors in School Children (JuvenTUM 3). Atherosclerosis 2012, 221, 242–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Said, E.A.; Al-Reesi, I.; Al-Shizawi, N.; Jaju, S.; Al-Balushi, M.S.; Koh, C.Y.; Al-Jabri, A.A.; Jeyaseelan, L. Defining IL-6 levels in healthy individuals: A meta-analysis. J. Med. Virol. 2021, 93, 3915–3924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deneva-Koycheva, T.I.; Vladimirova-Kitova, L.G.; Angelova, E.A.; Tsvetkova, T.Z. Serum levels of siCAM-1, sVCAM-1, sE-selectin, sP-selectin in healthy Bulgarian people. Folia. Med. 2011, 53, 22–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pai, V.; Bileck, A.; Hommer, N.; Janku, P.; Lindner, T.; Kauer, V.; Rumpf, B.; Haslacher, H.; Hagn, G.; Meier-Menches, S.M.; et al. Impaired retinal oxygen metabolism and perfusion are accompanied by plasma protein and lipid alterations in recovered COVID-19 patients. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalaw, F.G.P.; Warter, A.; Cavichini, M.; Knight, D.; Li, A.; Deussen, D.; Galang, C.; Heinke, A.; Mendoza, V.; Borooah, S.; et al. Retinal tissue and microvasculature loss in COVID-19 infection. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 5100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazantzis, D.; Machairoudia, G.; Theodossiadis, G.; Theodossiadis, P.; Chatziralli, I. Retinal microvascular changes in patients recovered from COVID-19 compared to healthy controls: A meta-analysis. Photodiagn. Photodyn Ther. 2023, 42, 103556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Global (n = 284) | Men (n = 88) | Women (n = 196) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean or n | SD or (%) | Mean or n | SD or (%) | Mean or n | SD or (%) | p-Value | |

| Conventional risk factors | |||||||

| Age, (years) | 52.71 | 11.94 | 55.70 | 12.28 | 51.32 | 11.54 | 0.004 |

| SBP, (mmHg) | 120.10 | 16.86 | 129.92 | 14.48 | 115.52 | 15.94 | <0.001 |

| DBP, (mmHg) | 76.85 | 11.11 | 82.34 | 11.04 | 74.30 | 10.20 | <0.001 |

| Antihypertensive drugs, n (%) | 79 | (26.0) | 34 | (35.1) | 45 | (21.7) | 0.014 |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 110 | (36.2) | 53 | (54.6) | 57 | (27.5) | <0.001 |

| FPG, (mg/dL) | 87.88 | 17.67 | 94.37 | 19.77 | 84.84 | 15.74 | <0.001 |

| Hypoglycemic drugs, n (%) | 32 | (10.5) | 18 | (18.6) | 14 | (6.8) | <0.001 |

| Diabetes Mellitus, n (%) | 37 | (12.2) | 22 | (22.7) | 15 | (7.3) | <0.001 |

| Cholesterol total, (mg/dL) | 187.49 | 34.50 | 182.11 | 32.94 | 190.01 | 35.00 | 0.063 |

| LDL cholesterol, (mg/dL) | 112.87 | 31.06 | 113.59 | 32.12 | 112.53 | 30.62 | 0.782 |

| HDL cholesterol, (mg/dL) | 56.98 | 13.66 | 48.78 | 10.86 | 60.82 | 13.15 | <0.001 |

| Triglycerides, (mg/dL) | 102.12 | 50.46 | 117.47 | 54.39 | 94.92 | 46.94 | <0.001 |

| Lipid-lowering drugs, n (%) | 75 | (24.8) | 40 | (41.7) | 35 | (17.0) | <0.001 |

| Dyslipidemia, n (%) | 172 | (57.0) | 67 | (69.1) | 105 | (51.2) | 0.003 |

| Lifestyle variables | |||||||

| Smoker, n (%) | 119 | (41.9) | 46 | (52.3) | 73 | (37.1) | 0.165 |

| Physical activity (METs/min/week) | 5113.18 | 5003.27 | 5394.02 | 5208.08 | 4982.21 | 4912.18 | 0.623 |

| Biomarkers of endothelial damage | |||||||

| IL-6 (pg/mL) | 2.14 | 1.99 | 2.57 | 2.34 | 1.94 | 1.77 | 0.027 |

| ICAM-1 (ng/mL) | 259.19 | 77.43 | 265.31 | 90.21 | 256.33 | 70.74 | 0.253 |

| VCAM-1 (ng/mL) | 537.32 | 166.15 | 57.37 | 197.54 | 520.32 | 146.71 | 0.279 |

| Global (n = 284) | Men (n = 88) | Women (n = 196) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean or n | SD or (%) | Mean or n | SD or (%) | Mean or n | SD or (%) | p-Value | |

| AV Index | 0.77 | 0.11 | 0.76 | 0.08 | 0.78 | 0.11 | 0.099 |

| Arteriolar calibre | 105.94 | 11.79 | 106.74 | 12.52 | 105.60 | 11.47 | 0.473 |

| Venular calibre | 140.2 | 15.26 | 143.07 | 15.85 | 138.69 | 14.84 | 0.031 |

| General obesity | |||||||

| Obesity, n (%) | 99 | (32.5) | 44 | (45.4) | 55 | (26.4) | <0.001 |

| BMI, (Kg/m2) | 27.97 | (5.55) | 29.6 | (4.64) | 27.21 | (5.78) | <0.001 |

| WHtR | 57.07 | (8.94) | 60.57 | (7.56) | 55.44 | (9.10) | <0.001 |

| BRI | 4.94 | (1.96) | 5.67 | (1.75) | 4.60 | (1.96) | <0.001 |

| Abdominal obesity | |||||||

| Abdominal obesity, n (%) | 147 | (48.2) | 49 | (50.5) | 98 | (47.1) | 0.580 |

| Waist circumference (cm) | 93.87 | (15.48) | 104.34 | (12.52) | 88.99 | (14.28) | <0.001 |

| AVI | 18.27 | (5.84) | 22.12 | (5.27) | 16.48 | (5.20) | <0.001 |

| Impedance measurement | |||||||

| BFM | 29.00 | (11.18) | 29.80 | (10.60) | 28.63 | (11.44) | 0.402 |

| FFM | 46.86 | (10.02) | 57.78 | (8.36) | 41.75 | (5.75) | <0.001 |

| SMM | 25.63 | (6.06) | 32.27 | (5.02) | 22.52 | (3.44) | <0.001 |

| β | IC (95%) | p-Value | R2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AV Index | ||||

| BMI | −0.003 | −0.005–0.000 | 0.030 | 0.047 |

| BRI | −0.008 | −0.015–−0.001 | 0.029 | 0.048 |

| WC | −0.001 | −0.002–0.000 | 0.011 | 0.054 |

| WHtR | −0.002 | −0.003–0.000 | 0.032 | 0.047 |

| AVI | −0.003 | −0.006–0.001 | 0.012 | 0.053 |

| BFM | −0.038 | −0.179–0.103 | 0.595 | 0.021 |

| FFM | −0.126 | −0.350–0.098 | 0.270 | 0.024 |

| SMM | −0.231 | −0.607–0.145 | 0.227 | 0.025 |

| Arteriolar calibre (µm) | ||||

| BMI | −0.154 | −0.429–0.121 | 0.271 | 0.024 |

| BRI | −0.190 | −1.009–0.628 | 0.647 | 0.020 |

| WC | −0.029 | −0.141–0.082 | 0.603 | 0.020 |

| WHtR | −0.056 | −0.235–0.123 | 0.541 | 0.013 |

| AVI | −0.054 | −0.349–0.241 | 0.719 | 0.020 |

| BFM | −0.038 | −0.179–0.103 | 0.595 | 0.021 |

| FFM | −0.126 | −0.350–0.098 | 0.270 | 0.024 |

| SMM | −0.231 | −0.607–0.145 | 0.227 | 0.025 |

| Venular calibre (µm) | ||||

| BMI | 0.317 | −0.031–0.665 | 0.074 | 0.052 |

| BRI | 1.076 | 0.043–2.109 | 0.041 | 0.056 |

| WC | 0.159 | 0.019–0.299 | 0.027 | 0.058 |

| WHtR | 0.212 | −0.014–0.439 | 0.066 | 0.053 |

| AVI | 0.462 | 0.091–0.833 | 0.015 | 0.062 |

| BFM | 0.195 | 0.018–0.371 | 0.031 | 0.056 |

| FFM | 0.180 | −0.103–0.463 | 0.211 | 0.045 |

| SMM | 0.302 | −0.174–0.777 | 0.212 | 0.045 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Alonso-Domínguez, R.; Vicente-García, T.; Arroyo-Romero, S.; Suárez-Moreno, N.; Navarro-Cáceres, A.; Domínguez-Martín, A.; Gómez-Sánchez, L.; Lugones-Sánchez, C.; García-Ortiz, L.; Ortega, A.; et al. Relationship Between Retinal Vascular Measurements and Anthropometric Indices in Patients Diagnosed with Persistent COVID-19. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 7857. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14217857

Alonso-Domínguez R, Vicente-García T, Arroyo-Romero S, Suárez-Moreno N, Navarro-Cáceres A, Domínguez-Martín A, Gómez-Sánchez L, Lugones-Sánchez C, García-Ortiz L, Ortega A, et al. Relationship Between Retinal Vascular Measurements and Anthropometric Indices in Patients Diagnosed with Persistent COVID-19. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(21):7857. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14217857

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlonso-Domínguez, Rosario, Teresa Vicente-García, Silvia Arroyo-Romero, Nuria Suárez-Moreno, Alicia Navarro-Cáceres, Andrea Domínguez-Martín, Leticia Gómez-Sánchez, Cristina Lugones-Sánchez, Luis García-Ortiz, Alicia Ortega, and et al. 2025. "Relationship Between Retinal Vascular Measurements and Anthropometric Indices in Patients Diagnosed with Persistent COVID-19" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 21: 7857. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14217857

APA StyleAlonso-Domínguez, R., Vicente-García, T., Arroyo-Romero, S., Suárez-Moreno, N., Navarro-Cáceres, A., Domínguez-Martín, A., Gómez-Sánchez, L., Lugones-Sánchez, C., García-Ortiz, L., Ortega, A., Gómez-Sánchez, M., Navarro-Matias, E., & Gómez-Marcos, M. A. (2025). Relationship Between Retinal Vascular Measurements and Anthropometric Indices in Patients Diagnosed with Persistent COVID-19. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(21), 7857. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14217857