Add-On Pharmacotherapy in Schizophrenia: Does It Improve Long-Term Outcomes? A Systematic Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

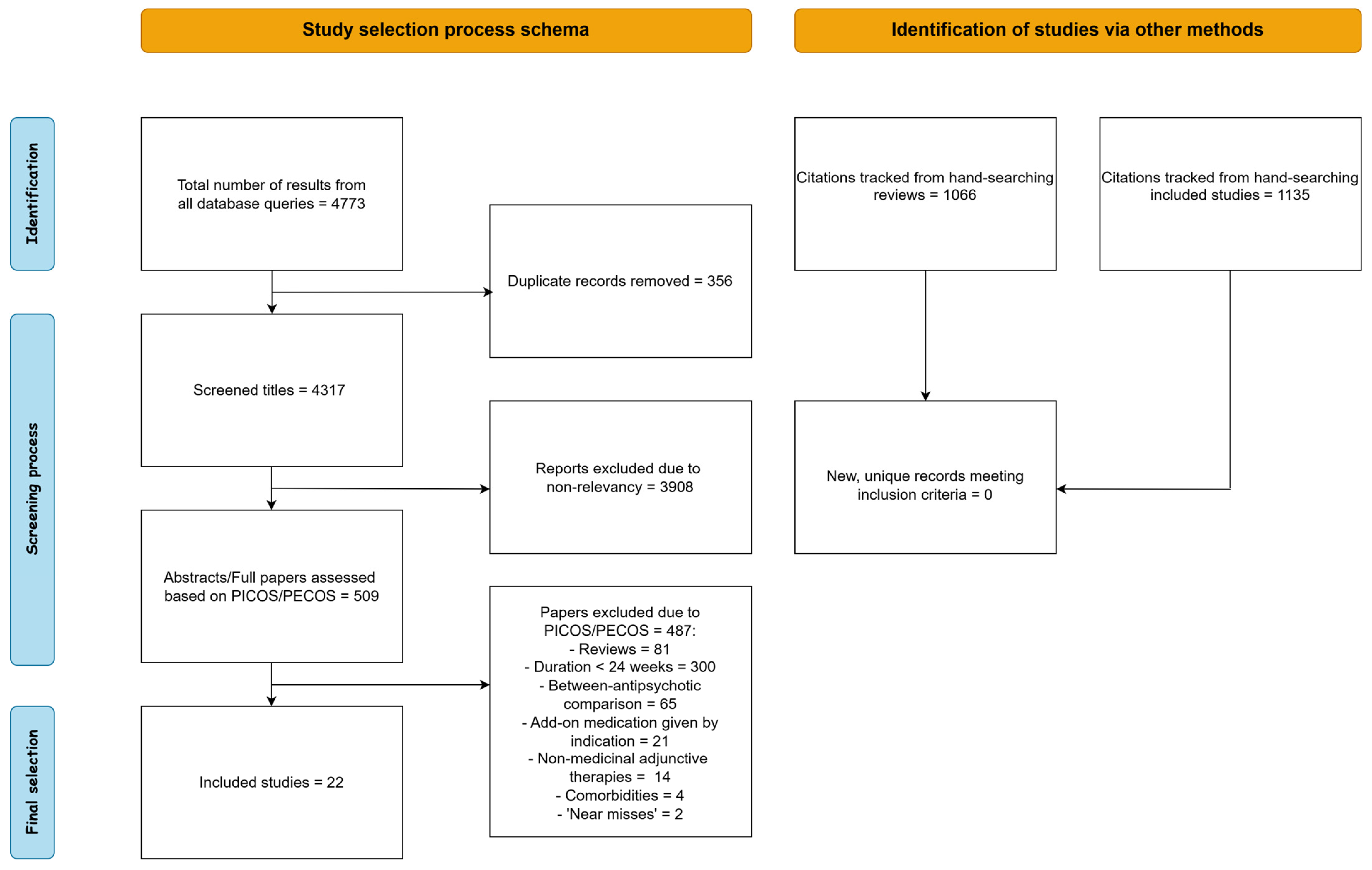

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Defining Add-On Treatment

2.2. Outcomes

2.3. Inclusion/Exclusion Criteria

2.4. Selection and Data Extraction Process

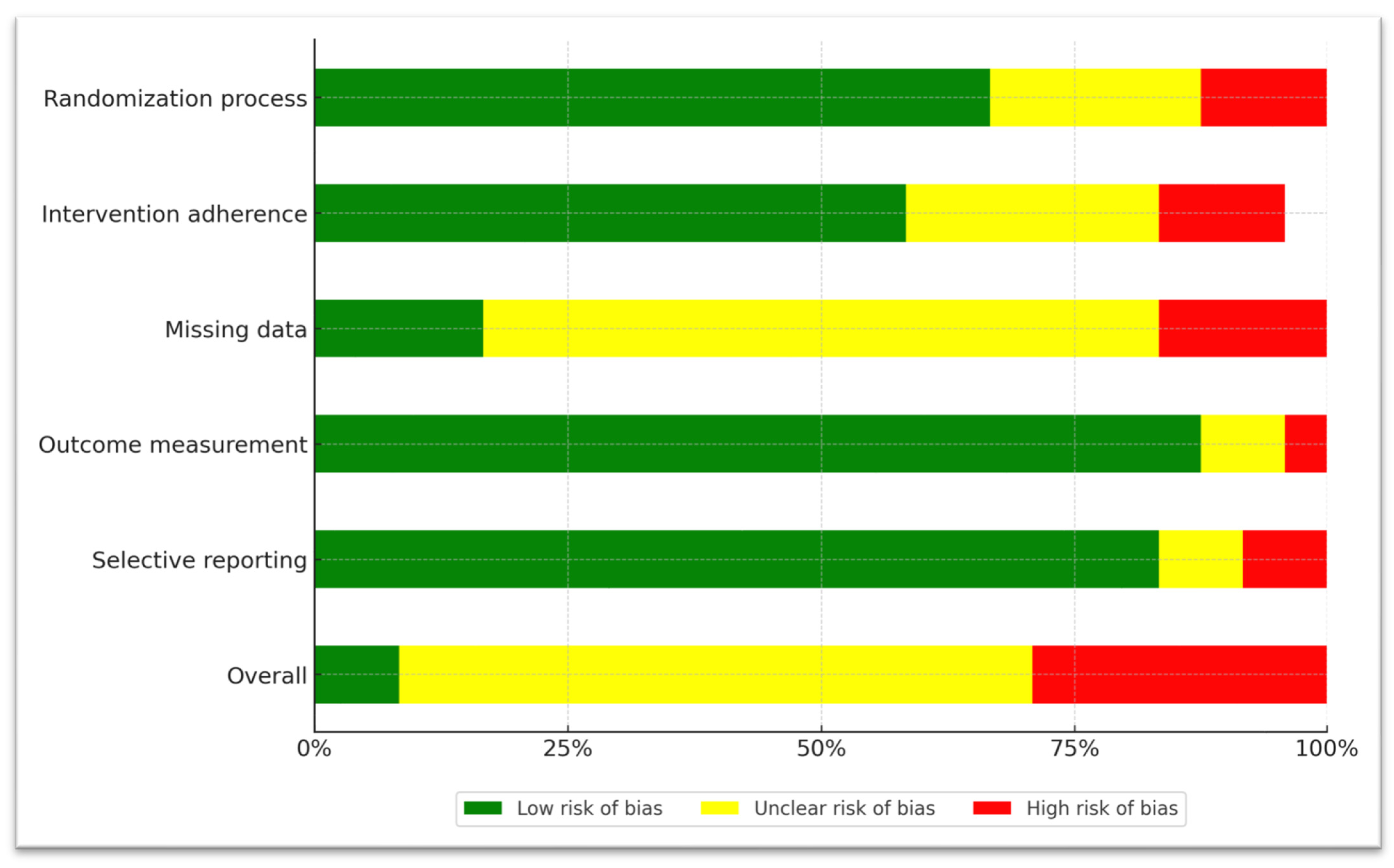

2.5. Risk-of-Bias Assessment of Included Studies

3. Results

3.1. Frequently Utilized Agents in Clinical Practice (Antidepressants, Mood Stabilizers)

3.2. Experimental Agents

3.2.1. Add-On Cognitive Enhancers

3.2.2. Add-On Antibiotics

3.2.3. Add-On Antioxidants/Anti-Inflammatory Agents

3.3. Relapse

3.4. Risk-of-Bias Assessment

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| SCZ | Schizophrenia |

| RCT | Randomized Controlled Trial |

| PANSS | Positive and Negative Symptom Scale |

| HAM-D | Hamilton Depression Rating Scale |

| CDSS | Calgary Depression Scale for Schizophrenia |

| BPRS | Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale |

| SANS | Scale for the Assessment of Negative Symptoms |

| CGI | Clinical Global Impression scale |

| GAF | Global Assessment of Functioning |

References

- Robinson, D.; Woerner, M.G.; Alvir, J.M.; Bilder, R.; Goldman, R.; Geisler, S.; Koreen, A.; Sheitman, B.; Chakos, M.; Mayerhoff, D.; et al. Predictors of relapse following response from a first episode of schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 1999, 56, 241–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Remington, G.; Addington, D.; Honer, W.; Ismail, Z.; Raedler, T.; Teehan, M. Guidelines for the Pharmacotherapy of Schizophrenia in Adults. Can. J. Psychiatry 2017, 62, 604–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Rubio, J.M.; Taipale, H.; Correll, C.U.; Tanskanen, A.; Kane, J.M.; Tiihonen, J. Psychosis breakthrough on antipsychotic maintenance: Results from a nationwide study. Psychol. Med. 2020, 50, 1356–1367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goff, D.C.; Midha, K.K.; Sarid-Segal, O.; Hubbard, J.W.; Amico, E. A placebo-controlled trial of fluoxetine added to neuroleptic in patients with schizophrenia. Psychopharmacology 1995, 117, 417–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wolkowitz, O.M.; Turetsky, N.; Reus, V.I.; Hargreaves, W.A. Benzodiazepine augmentation of neuroleptics in treatment-resistant schizophrenia. Psychopharmacol. Bull. 1992, 28, 291–295. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Citrome, L.; Levine, J.; Allingham, B. Changes in use of valproate and other mood stabilizers for patients with schizophrenia from 1994 to 1998. Psychiatr. Serv. 2000, 51, 634–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silver, H.; Susser, E.; Danovich, L.; Bilker, W.; Youdim, M.; Goldin, V.; Weinreb, O. SSRI augmentation of antipsychotic alters expression of GABA(A) receptor and related genes in PMC of schizophrenia patients. Int. J. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2011, 14, 573–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Citrome, L. Adjunctive lithium and anticonvulsants for the treatment of schizophrenia: What is the evidence? Expert Rev. Neurother. 2009, 9, 55–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Terevnikov, V.; Joffe, G.; Stenberg, J.H. Randomized Controlled Trials of Add-On Antidepressants in Schizophrenia. Int. J. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2015, 18, pyv049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Helfer, B.; Samara, M.T.; Huhn, M.; Klupp, E.; Leucht, C.; Zhu, Y.; Engel, R.R.; Leucht, S. Efficacy and Safety of Antidepressants Added to Antipsychotics for Schizophrenia: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Am. J. Psychiatry 2016, 173, 876–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dold, M.; Li, C.; Gillies, D.; Leucht, S. Benzodiazepine augmentation of antipsychotic drugs in schizophrenia: A meta-analysis and Cochrane review of randomized controlled trials. Eur. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2013, 23, 1023–1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ribeiz, S.R.; Bassitt, D.P.; Arrais, J.A.; Avila, R.; Steffens, D.C.; Bottino, C.M. Cholinesterase inhibitors as adjunctive therapy in patients with schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder: A review and meta-analysis of the literature. CNS Drugs 2010, 24, 303–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vayısoğlu, S.; Karahan, S.; Anıl Yağcıoğlu, A.E. Augmentation of Antipsychotic Treatment with Memantine in Patients with Schizophrenia: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Turk Psikiyatri Derg. 2019, 30, 253–259. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Zheng, W.; Li, X.H.; Yang, X.H.; Cai, D.B.; Ungvari, G.S.; Ng, C.H.; Wang, S.B.; Wang, Y.Y.; Ning, Y.P.; Xiang, Y.T. Adjunctive memantine for schizophrenia: A meta-analysis of randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trials. Psychol. Med. 2018, 48, 72–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wittkampf, L.C.; Arends, J.; Timmerman, L.; Lancel, M. A review of modafinil and armodafinil as add-on therapy in antipsychotic-treated patients with schizophrenia. Ther. Adv. Psychopharmacol. 2012, 2, 115–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Kishi, T.; Sakuma, K.; Hatano, M.; Iwata, N. N-acetylcysteine for schizophrenia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2023, 77, 119–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, W.; Zhu, X.M.; Zhang, Q.E.; Yang, X.H.; Cai, D.B.; Li, L.; Li, X.B.; Ng, C.H.; Ungvari, G.S.; Ning, Y.P.; et al. Adjunctive intranasal oxytocin for schizophrenia: A meta-analysis of randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trials. Schizophr. Res. 2019, 206, 13–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nitta, M.; Kishimoto, T.; Müller, N.; Weiser, M.; Davidson, M.; Kane, J.M.; Correll, C.U. Adjunctive use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs for schizophrenia: A meta-analytic investigation of randomized controlled trials. Schizophr. Bull. 2013, 39, 1230–1241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Sommer, I.E.; de Witte, L.; Begemann, M.; Kahn, R.S. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs in schizophrenia: Ready for practice or a good start? A meta-analysis. J. Clin. Psychiatry 2012, 73, 414–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Emsley, R.; Oosthuizen, P.; van Rensburg, S.J. Clinical potential of omega-3 fatty acids in the treatment of schizophrenia. CNS Drugs 2003, 17, 1081–1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuppili, P.P.; Menon, V.; Sathyanarayanan, G.; Sarkar, S.; Andrade, C. Efficacy of adjunctive D-Cycloserine for the treatment of schizophrenia: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J. Neural. Transm. 2021, 128, 253–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiang, Y.Q.; Zheng, W.; Wang, S.B.; Yang, X.H.; Cai, D.B.; Ng, C.H.; Ungvari, G.S.; Kelly, D.L.; Xu, W.Y.; Xiang, Y.T. Adjunctive minocycline for schizophrenia: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Eur. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2017, 27, 8–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fond, G.; Mallet, J.; Urbach, M.; Benros, M.E.; Berk, M.; Billeci, M.; Boyer, L.; Correll, C.U.; Fornaro, M.; Kulkarni, J.; et al. Adjunctive agents to antipsychotics in schizophrenia: A systematic umbrella review and recommendations for amino acids, hormonal therapies and anti-inflammatory drugs. BMJ Ment. Health 2023, 26, e300771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Stroup, T.S.; Gerhard, T.; Crystal, S.; Huang, C.; Tan, Z.; Wall, M.M.; Mathai, C.; Olfson, M. Comparative Effectiveness of Adjunctive Psychotropic Medications in Patients with Schizophrenia. JAMA Psychiatry 2019, 76, 508–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Wu, C.S.; Lin, Y.J.; Liu, S.K. Benzodiazepine use among patients with schizophrenia in Taiwan: A nationwide population-based survey. Psychiatr. Serv. 2011, 62, 908–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiang, Y.T.; Dickerson, F.; Kreyenbuhl, J.; Ungvari, G.S.; Wang, C.Y.; Si, T.M.; Lee, E.H.; He, Y.L.; Chiu, H.F.; Yang, S.Y.; et al. Adjunctive mood stabilizer and benzodiazepine use in older Asian patients with schizophrenia, 2001–2009. Pharmacopsychiatry 2012, 45, 217–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiang, Y.T.; Ungvari, G.S.; Wang, C.Y.; Si, T.M.; Lee, E.H.; Chiu, H.F.; Lai, K.Y.; He, Y.L.; Yang, S.Y.; Chong, M.Y.; et al. Adjunctive antidepressant prescriptions for hospitalized patients with schizophrenia in Asia (2001–2009). Asia Pac. Psychiatry 2013, 5, E81–E87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Puranen, A.; Koponen, M.; Lähteenvuo, M.; Tanskanen, A.; Tiihonen, J.; Taipale, H. Real-world effectiveness of antidepressant use in persons with schizophrenia: Within-individual study of 61,889 subjects. Schizophrenia 2023, 9, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Tiihonen, J.; Mittendorfer-Rutz, E.; Torniainen, M.; Alexanderson, K.; Tanskanen, A. Mortality and Cumulative Exposure to Antipsychotics, Antidepressants, and Benzodiazepines in Patients with Schizophrenia: An Observational Follow-Up Study. Am. J. Psychiatry 2016, 173, 600–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G.; PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009, 6, e1000097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreasen, N.C.; Carpenter WTJr Kane, J.M.; Lasser, R.A.; Marder, S.R.; Weinberger, D.R. Remission in schizophrenia: Proposed criteria and rationale for consensus. Am. J. Psychiatry 2005, 162, 441–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kay, S.R.; Fiszbein, A.; Opler, L.A. The Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) for schizophrenia. Schizophr. Bull. 1987, 13, 261–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamilton, M. A rating scale for depression. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 1960, 23, 56–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Addington, D.; Addington, J.; Schissel, B. A depression rating scale for schizophrenics. Schizophr. Res. 1990, 3, 247–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Overall, J.E.; Gorham, D.R. The Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale. Psychol. Rep. 1962, 10, 799–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreasen, N.C. Negative symptoms in schizophrenia. Definition and reliability. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 1982, 39, 784–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guy, W. ECDEU Assessment Manual for Psychopharmacology, Revised; U.S. Department of Health, Education, and Welfare, Public Health Service, Alcohol, Drug Abuse, and Mental Health Administration, NIMH Psychopharmacology Research Branch: Rockville, MD, USA, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, S.H.; Thornicroft, G.; Coffey, M.; Dunn, G. A Brief Mental Health Outcome Scale: Reliability and Validity of the Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF). Br. J. Psychiatry 1995, 166, 654–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sterne, J.A.C.; Savović, J.; Page, M.J.; Elbers, R.G.; Blencowe, N.S.; Boutron, I.; Cates, C.J.; Cheng, H.Y.; Corbett, M.S.; Eldridge, S.M.; et al. RoB 2: A revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ 2019, 366, l4898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hirayasu, Y.; Sato, S.; Takahashi, H.; Iida, S.; Shuto, N.; Yoshida, S.; Funatogawa, T.; Yamada, T.; Higuchi, T. A double-blind randomized study assessing safety and efficacy following one-year adjunctive treatment with bitopertin, a glycine reuptake inhibitor, in Japanese patients with schizophrenia. BMC Psychiatry 2016, 16, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Anand, R.; Turolla, A.; Chinellato, G.; Roy, A.; Hartman, R.D. Therapeutic Effect of Evenamide, a Glutamate Inhibitor, in Patients With Treatment-Resistant Schizophrenia (TRS): Final, 1-Year Results from a Phase 2, Open-Label, Rater-Blinded, Randomized, International Clinical Trial. Int. J. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2024, 28, pyae061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Bugarski-Kirola, D.; Blaettler, T.; Arango, C.; Fleischhacker, W.W.; Garibaldi, G.; Wang, A.; Dixon, M.; Bressan, R.A.; Nasrallah, H.; Lawrie, S.; et al. Bitopertin in Negative Symptoms of Schizophrenia-Results from the Phase III FlashLyte and DayLyte Studies. Biol. Psychiatry 2017, 82, 8–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Friedman, J.I.; Ocampo, R.; Elbaz, Z.; Parrella, M.; White, L.; Bowler, S.; Davis, K.L.; Harvey, P.D. The effect of citalopram adjunctive treatment added to atypical antipsychotic medications for cognitive performance in patients with schizophrenia. J. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 2005, 25, 237–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Usall, J.; López-Carrilero, R.; Iniesta, R.; Roca, M.; Caballero, M.; Rodriguez-Jimenez, R.; Oliveira, C.; Bernardo, M.; Corripio, I.; Sindreu, S.D.; et al. Double-blind, placebo-controlled study of the efficacy of reboxetine and citalopram as adjuncts to atypical antipsychotics for negative symptoms of schizophrenia. J. Clin. Psychiatry 2014, 75, 608–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barnes, T.R.; Leeson, V.C.; Paton, C.; Costelloe, C.; Simon, J.; Kiss, N.; Osborn, D.; Killaspy, H.; Craig, T.K.; Lewis, S.; et al. Antidepressant Controlled Trial For Negative Symptoms In Schizophrenia (ACTIONS): A double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomised clinical trial. Health Technol. Assess. 2016, 20, 1–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Goff, D.C.; Freudenreich, O.; Cather, C.; Holt, D.; Bello, I.; Diminich, E.; Tang, Y.; Ardekani, B.A.; Worthington, M.; Zeng, B.; et al. Citalopram in first episode schizophrenia: The DECIFER trial. Schizophr. Res. 2019, 208, 331–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, H.; Xu, J.; Lang, X.; Wu, H.E.; Xiu, M.H.; Zhang, X.Y. Comparison of Efficacy and Safety Between Low-Dose Ziprasidone in Combination With Sertraline and Ziprasidone Monotherapy for Treatment-Resistant Patients With Acute Exacerbation Schizophrenia: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 863588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Zhu, C.; Guan, X.; Wang, Y.; Liu, J.; Kosten, T.R.; Xiu, M.; Wu, F.; Zhang, X. Low-Dose Ziprasidone in Combination with Sertraline for First-Episode Drug-Naïve Patients with Schizophrenia: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Neurotherapeutics 2022, 19, 1037–1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Lang, X.; Xue, M.; Zang, X.; Wu, F.; Xiu, M.; Zhang, X. Efficacy of low-dose risperidone in combination with sertraline in first-episode drug-naïve patients with schizophrenia: A randomized controlled open-label study. J. Transl. Med. 2023, 21, 432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Zoccali, R.; Muscatello, M.R.; Bruno, A.; Cambria, R.; Micò, U.; Spina, E.; Meduri, M. The effect of lamotrigine augmentation of clozapine in a sample of treatment-resistant schizophrenic patients: A double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Schizophr. Res. 2007, 93, 109–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lenzi, A.; Maltinti, E.; Poggi, E.; Fabrizio, L.; Coli, E. Effects of rivastigmine on cognitive function and quality of life in patients with schizophrenia. Clin. Neuropharmacol. 2003, 26, 317–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, T.; Reed, C.; Aasen, I.; Kumari, V. Cognitive effects of adjunctive 24-weeks Rivastigmine treatment to antipsychotics in schizophrenia: A randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind investigation. Schizophr. Res. 2006, 85, 73–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lindenmayer, J.P.; Khan, A. Galantamine augmentation of long-acting injectable risperidone for cognitive impairments in chronic schizophrenia. Schizophr. Res. 2011, 125, 267–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kane, J.M.; Yang, R.; Youakim, J.M. Adjunctive armodafinil for negative symptoms in adults with schizophrenia: A double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Schizophr. Res. 2012, 135, 116–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Veerman, S.R.; Schulte, P.F.; Smith, J.D.; de Haan, L. Memantine augmentation in clozapine-refractory schizophrenia: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled crossover study. Psychol. Med. 2016, 46, 1909–1921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Kumar, P.N.S.; Mohemmedali, S.P.; Anish, P.K.; Andrade, C. Cognitive effects with rivastigmine augmentation of risperidone: A 12-month, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study in schizophrenia. Indian J. Psychiatry 2017, 59, 219–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Goff, D.C.; Herz, L.; Posever, T.; Shih, V.; Tsai, G.; Henderson, D.C.; Freudenreich, O.; Evins, A.E.; Yovel, I.; Zhang, H.; et al. A six-month, placebo-controlled trial of D-cycloserine co-administered with conventional antipsychotics in schizophrenia patients. Psychopharmacology 2005, 179, 144–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levkovitz, Y.; Mendlovich, S.; Riwkes, S.; Braw, Y.; Levkovitch-Verbin, H.; Gal, G.; Fennig, S.; Treves, I.; Kron, S. A double-blind, randomized study of minocycline for the treatment of negative and cognitive symptoms in early-phase schizophrenia. J. Clin. Psychiatry 2010, 71, 138–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaudhry, I.B.; Hallak, J.; Husain, N.; Minhas, F.; Stirling, J.; Richardson, P.; Dursun, S.; Dunn, G.; Deakin, B. Minocycline benefits negative symptoms in early schizophrenia: A randomised double-blind placebo-controlled clinical trial in patients on standard treatment. J. Psychopharmacol. 2012, 26, 1185–1193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deakin, B.; Suckling, J.; Barnes, T.R.E.; Byrne, K.; Chaudhry, I.B.; Dazzan, P.; Drake, R.J.; Giordano, A.; Husain, N.; Jones, P.B.; et al. The benefit of minocycline on negative symptoms of schizophrenia in patients with recent-onset psychosis (BeneMin): A randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Psychiatry 2018, 5, 885–894, Erratum in Lancet Psychiatry 2018, 5, e28. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(18)30431-0. PMID: 30322824; PMCID: PMC6206257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Berk, M.; Copolov, D.; Dean, O.; Lu, K.; Jeavons, S.; Schapkaitz, I.; Anderson-Hunt, M.; Judd, F.; Katz, F.; Katz, P.; et al. N-acetyl cysteine as a glutathione precursor for schizophrenia--a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Biol. Psychiatry 2008, 64, 361–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pawełczyk, T.; Grancow-Grabka, M.; Kotlicka-Antczak, M.; Trafalska, E.; Pawełczyk, A. A randomized controlled study of the efficacy of six-month supplementation with concentrated fish oil rich in omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids in first episode schizophrenia. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2016, 73, 34–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Conus, P.; Seidman, L.J.; Fournier, M.; Xin, L.; Cleusix, M.; Baumann, P.S.; Ferrari, C.; Cousins, A.; Alameda, L.; Gholam-Rezaee, M.; et al. N-acetylcysteine in a Double-Blind Randomized Placebo-Controlled Trial: Toward Biomarker-Guided Treatment in Early Psychosis. Schizophr. Bull. 2018, 44, 317–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Neill, E.; Rossell, S.L.; Yolland, C.; Meyer, D.; Galletly, C.; Harris, A.; Siskind, D.; Berk, M.; Bozaoglu, K.; Dark, F.; et al. N-Acetylcysteine (NAC) in Schizophrenia Resistant to Clozapine: A Double-Blind, Randomized, Placebo-Controlled Trial Targeting Negative Symptoms. Schizophr. Bull. 2022, 48, 1263–1272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Wallwork, R.S.; Fortgang, R.; Hashimoto, R.; Weinberger, D.R.; Dickinson, D. Searching for a consensus five-factor model of the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale for schizophrenia. Schizophr. Res. 2012, 137, 246–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Jiménez-García, K.L.; Cervantes-Escárcega, J.L.; Canul-Medina, G.; Lisboa-Nascimento, T.; Jiménez-Trejo, F. The Role of Serotoninomics in Neuropsychiatric Disorders: Anthranilic Acid in Schizophrenia. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 7124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Salokangas, R.K.; Saarijärvi, S.; Taiminen, T.; Kallioniemi, H.; Lehto, H.; Niemi, H.; Tuominen, J.; Ahola, V.; Syvälahti, E. Citalopram as an adjuvant in chronic schizophrenia: A double-blind placebo-controlled study. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 1996, 94, 175–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mendelsohn, E.; Rosenthal, M.; Bohiri, Y.; Werber, E.; Kotler, M.; Strous, R.D. Rivastigmine augmentation in the management of chronic schizophrenia with comorbid dementia: An open-label study investigating effects on cognition, behaviour and activities of daily living. Int. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 2004, 19, 319–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bobo, W.V.; Woodward, N.D.; Sim, M.Y.; Jayathilake, K.; Meltzer, H.Y. The effect of adjunctive armodafinil on cognitive performance and psychopathology in antipsychotic-treated patients with schizophrenia/schizoaffective disorder: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Schizophr. Res. 2011, 130, 106–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Plane, J.M.; Shen, Y.; Pleasure, D.E.; Deng, W. Prospects for minocycline neuroprotection. Arch. Neurol. 2010, 67, 1442–1448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Khodaie-Ardakani, M.R.; Mirshafiee, O.; Farokhnia, M.; Tajdini, M.; Hosseini, S.M.; Modabbernia, A.; Rezaei, F.; Salehi, B.; Yekehtaz, H.; Ashrafi, M.; et al. Minocycline add-on to risperidone for treatment of negative symptoms in patients with stable schizophrenia: Randomized double-blind placebo-controlled study. Psychiatry Res. 2014, 215, 540–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Parameter | Inclusion | Exclusion |

|---|---|---|

| Population | Schizophrenia spectrum disorder patients | Schizophrenia patients with neurological comorbidities or alcohol/substance abuse |

| Intervention/ Exposure | Add-on, non-antipsychotic medication administered for 24 weeks or more, irrespective of indication | Treatment duration less than 24 weeks, treatment with add-on medication based on specific indications |

| Comparison | Treatment as usual with atypical antipsychotics or haloperidol | Comparison to non-medicinal adjunctive therapy such as psychotherapy or ECT |

| Outcome | Clinical scales: PANSS, CDSS, SANS, HAMD, CGI, GAF, BPRS, GAF and relapse % | Solely cognitive assessments |

| Study Design | Both RCTs and open-label, non-randomized trials | Reviews or meta-analyses, case reports and case series |

| Antidepressants (SSRIs, SNRIs) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study (Country) | Add-On Compound | Daily Dosage | Design/Duration | Sample | Diagnosis | Main Outcomes | Statistical Results | Relapse (%) | Synthesis of Main Findings |

| Friedman et al. 2005 [44] (USA) | Citalopram | 20 mg up to 40 mg | 24-week, double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled, cross-over |

| SCZ | PANSS, cognitive assessment every 2 weeks till 24 weeks. | ANOVA, for mean difference between baseline and endpoint, placebo and Citalopram PANSS Positive F = 1.15, p = 0.29 PANSS Negative F = 0.49, p = 0.49 PANSS General F = 1.64, p = 0.21 | 0 (0%)—total | Citalopram had no effect on clinical symptomatology or any cognitive metric in a small sample of SCZ patients. |

| Usall et al. 2014 [45] (Spain) | Citalopram or Reboxetine | 30 mg–8 mg | 24-week, double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled |

| SCZ, negative symptoms | PANSS, SANS at baseline, 12 and 24 weeks. | Linear mixed models time by group effect: SANS total F = 0.78, p = 0.588 PANSS negative F = 0.83, p = 0.553 PANSS positive F = 1.55, p = 0.172 PANSS general F = 1.44, p = 0.208 PANSS total F = 0.70, p = 0.651 | No information | Neither Citalopram, nor Reboxetine significantly ameliorated clinical outcome after 6 months of treatment, contrary to short-term past trials. |

| Barnes et al. 2016 [46] (UK) | Citalopram | 20 mg up to 40 mg | 48-week, double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled |

| SCZ, with persistent negative symptoms | PANSS, CDSS at baseline and at 12, 36, 48 weeks | Linear regression showed no significant difference between treatment groups. Between-group differences in: PANSS negative subscale: −1.54 (−4.91 to 1.8, p = 0.36) PANSS total: −1.1 (−7.7 to 5.6, p > 0.05) | No information | Citalopram did not provide any additional benefit, neither regarding positive and negative symptoms nor in quality of life. |

| Goff et al. 2019 [47] (USA, China) | Citalopram | 20 mg up to 40 mg | 52-week, double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled |

| SCZ spectrum, first-episode | CDSS, weekly up to week 8, then every 4 weeks, SANS and BPRS every 4 weeks till 52 weeks. | Linear mixed-model group by visit interaction effect (SE = Standard Error): CDSS difference from baseline −0.7048, SE = 0.3027, t = −2.33, p = 0.02 BPRS total, difference from baseline 0.7894, SE = 1.6042, t = 0.49, p = 0.62 SANS total, difference from baseline 3.3046, SE = 1.7042, t = 1.94, p = 0.05 | 6 (12.5%)—Citalopram 2 (4.2%)—Placebo | While add-on Citalopram did have a marginally significant effect on negative symptoms, it did not ameliorate global clinical scores. |

| Shi et al. 2022 [48] (China) | Sertraline | 50 mg | 24-week, double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled |

| SCZ, treatment resistant | PANSS, HAMD, CGI-S at baseline, 4, 8, 12 and 24 weeks. | Repeated measures ANOVA group by time interaction effects: PANSS negative F = 24.7, p < 0.001 PANSS positive F = 0.6, p = 0.49 PANSS general F = 2.0, p = 0.09 PANSS total F = 4.0, p = 0.04 HAM-D F = 16.0, p < 0.001 | 0 (0%)—Sertraline 0 (0%)—Placebo | Add-on Sertraline was found to improve negative and depressive symptoms, as well as total psychopathology. The same was not observed for general and positive psychopathology. |

| Zhu et al. 2022 [49] (China) | Sertraline | 50 mg | 24-week, double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled |

| SCZ, first-episode | PANSS, HAMD, CGI-S at baseline, 2, 4, 8, 12 and 24 weeks. | Repeated measures ANOVA group by time interaction effects: PANSS negative F = 1.3, p = 0.42 PANSS positive F = 0.9, p = 0.38 PANSS general F = 12.3, p < 0.001 PANSS total F = 17.9, p < 0.001 HAM-D F = 78.3, p < 0.001 | 0 (0%)—Sertraline 0 (0%)—Placebo | Add-on Sertraline produced better results regarding general and depressive symptomatology. The positive and negative dimension improvement in time, did not differ between treatment groups. |

| Lang et al. 2023 [50] (China) | Sertraline | 50 up to 100 mg | 24-week, open-label, randomized, placebo-controlled |

| SCZ, first-episode | PANSS, HAMD, at baseline, 4, 8, 12 and 24 weeks. | Repeated measures ANOVA group by time interaction effects: PANSS positive F = 8.2, p = 0.002 PANSS negative F = 78.0, p < 0.001 PANSS general F = 24.2, p < 0.001 PANSS total F = 39.2, p < 0.001 HAM-D F = 90.5, p < 0.001 | No information | Sertraline in addition to Risperidone showed significant benefits compared to Risperidone alone, regarding all psychopathological metrics. Placebo effect cannot be ruled out. |

| Mood Stabilizers | |||||||||

| Zoccali et al. 2007 [51] (Italy) | Lamotrigine | 200 mg | 24-week, double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled |

| SCZ, treatment resistant | BPRS, CDSS, SANS at baseline, 12 and 24 weeks | Mann–Whitney U test revealed significant between group differences at 24 weeks: SANS total, U = 756, p < 0.001, BPRS, U = 109, p < 0.001, CDSS, U = 174.5, p = 0.004. | 0 (0%)—Lamotrigine 0 (0%)—Placebo | Lamotrigine provided long-term clinical benefits, regarding negative and depressive symptoms, as well as overall psychopathology. |

| Cognitive Enhancers (Acetylcholinesterase Inhibitors, NMDA Antagonists and Others) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study (Country) | Add-On Compound | Daily Dosage | Design/Duration | Sample | Diagnosis | Main Outcomes | Statistical Results | Relapse (%) | Synthesis of Main Findings |

| Lenzi et al. 2003 [52] (Italy) | Rivastigmine | 6 mg | 52-week, open-label |

| SCZ | BPRS, cognitive assessment at baseline, 4, 8, 12, 16 and 52 weeks. | BPRS psychotic symptoms factors were not affected. | 0 (0%)—total | Rivastigmine seemed to improve cognitive symptoms and quality of life, while it did not affect psychotic symptoms. Study results should be interpreted with caution, given the open-label design, and small sample size. |

| Sharma et al. 2006 [53] (UK) | Rivastigmine | 12 mg | 24-week, double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled |

| SCZ | PANSS, cognitive assessment at baseline, 12 and 24 weeks | ANOVA revealed neither significant treatment nor time-by-treatment effects for PANSS or any cognitive metric. Time by Treatment: PANSS positive: F = 0.25, p = 0.78 PANSS negative: F = 0.98, p = 0.40 PANSS general: F = 0.55, p = 0.58 PANSS total: F = 0.60, p = 0.55 | 1 (9%)—Rivastigmine 0 (0%)—Placebo | In a small sample, add-on Rivastigmine had no effect compared to placebo in any of the clinical or cognitive variables that were tested. |

| Lindenmayer et al. 2011 [54] (USA) | Galantamine | 24 mg | 24-week extension, double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled |

| SCZ spectrum | 5-factor PANSS and cognitive assessment at baseline and at 24 weeks. | ANCOVA model with effects for treatment group, pooled site and baseline value: 2.8-point increase for general psychopathology p = 0.002, for Galantamine. Implementing the five-factor model for PANSS, resulted in zero significant between group differences (all p > 0.05). | 3 (20%)—Galantamine 1 (6%)—Placebo | Cognitive impairments and overall clinical symptomatology did not seem to improve with the addition of Galantamine, albeit in a small sample. |

| Kane et al. 2012 [55] (USA) | Armodafinil | 150, 200 or 250 mg | 24-week, double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled |

| SCZ, with negative symptoms | PANSS, CGI-S and cognitive assessment at baseline and every 2 weeks till 24 weeks. | Mean (SD) difference between baseline and final visit, for the 3 Armodafinil groups and placebo: 150 mg 200 mg 250 mg Placebo PANSS negative −1.9 (3.75) −2.3 (3.57) −2.0 (3.29) −2.2 (4.08) PANSS positive 0.2 (3.20) 0.2 (3.37) −0.2 (2.78) 0.2 (4.41) PANSS total −2.9 (10.33) −3.5 (10.66) −3.5 (8.51) −3.0 (12.32) All p values in ANCOVA were larger than 0.5. | 9 (4%)—Armodafinil 3 (4%)—Placebo | Add-on Modafinil exhibited no benefit compared to placebo regarding clinical symptomatology or relapse prevention. This result was the same for all three dosages used in this study. |

| Veerman et al. 2016 [56] (Netherlands) | Memantine | 20 mg | 26-week, double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled, cross-over |

| SCZ, treatment resistant | PANSS, CGI-S, cognitive assessment at 12, 14 and 26 weeks. | Memantine phase in comparison with the placebo phase: PANSS negative symptoms (F = 4.17, ES = 0.29, p = 0.043) PANSS positive symptoms (F = 1.008, ES = 0.15, p = 0.299) PANSS total symptoms (F = 1.869, ES = 0.19, p = 0.174) CGI (F = 0.591, ES = 0.11, p = 0.443) | 4 (15%)—Memantine 3 (11%)—Placebo | Memantine had a significant effect in reducing negative symptoms specifically, while no difference was reported for positive and total psychopathology. |

| Kumar et al. 2017 [57] (India) | Rivastigmine | up to 6 mg | 52-week, double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled |

| SCZ, stable | PANSS, CGI-I, cognitive assessment at 12, 24, 36 and 52 weeks | Two-way repeated measures ANOVA for PANSS total score. Rivastigmine-Placebo at baseline: 43.1 (12.2)–43.2 (8.1), p = 0.99, and at 12 months: 36.1 (6.4)–38.6 (6.2) F = 8.9, p < 0.01. | 1 (3.5%)—Rivastigmine 0 (0%)—Placebo | Rivastigmine had an added positive impact on positive and negative symptomatology and on some of the assessed cognitive markers. |

| Antibiotics | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study (Country) | Add-on Compound | Daily Dosage | Design/Duration | Sample | Diagnosis | Main Outcomes | Statistical Results | Relapse (%) | Synthesis of Main Findings |

| Geoff et al. 2004 [58] (USA) | D-Cycloserine | 50 mg | 24-week, double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled |

| SCZ, predominant negative symptoms | SANS, PANSS at baseline, week 1, 2, 4 and then every 4 weeks till 24 weeks. | Mean normalized area under the curve for SANS total, from baseline to 24 weeks: D-Cycloserine: 0.93 ± 0.19, Placebo: 0.96 ± 0.12, 95% CI: (−0.12, 0.06) Same results for PANSS. | 0 (0%)—D-Cycloserine 0 (0%)—Placebo | D-Cycloserine provided no added benefits compared to antipsychotics alone, on any clinical measure. |

| Levkovitz et al. 2010 [59] (Israel) | Minocycline | 200 mg | 24-week, double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled |

| SCZ, PANSS total > 60 | SANS, PANSS, CGI and cognitive assessment at baseline, week 1, 2 and then every 4 weeks till 24 weeks. | Repeated measures ANOVA time-by-treatment interaction effect: SANS total p < 0.01, effect size r = 0.46 PANSS negative p = 0.43, effect size r = 0.23 PANSS positive p = 0.39, effect size r = 0.24 PANSS general p = 0.81, effect size r = 0.13 PANSS total p = 0.48, effect size r = 0.21 CGI p < 0.01, effect size r = 0.61 | 1 (2.7%)—Minocycline 1 (5.5%)—Placebo | Add-on Minocycline seemed to alleviate negative symptoms measured by the SANS and CGI scales. However, it did not influence the PANSS negative, or any other PANSS symptom dimension. |

| Chaudhry et al. 2012 [60] (Brazil, Pakistan) | Minocycline | 200 mg | 52-week, double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled |

| SCZ spectrum, stable | PANSS, CGI at baseline, 24 and 52 weeks. | Analysis was performed for each center (Pakistan, Brazil). We present the combined ANCOVA treatment effect estimates (95% CI): PANSS negative 3.53 (1.55, 5.51) PANSS positive 2.01 (0.51, 3.50) PANSS general 3.13 (−0.14, 6.41) PANSS total 8.52 (2.57, 14.48) | 0 (0%)—Minocycline 2 (2.7%)—Placebo | Negative symptomatology was significantly affected by Minocycline in both study centers. Positive, general, and total symptomatology also improved. However, there was a treatment-by-country effect). |

| Deakin et al. 2018 [61] (UK) | Minocycline | 300 mg | 48-week, double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled |

| SCZ spectrum, first-episode | PANSS, CDSS, GAF at 8, 24, 36, 48 weeks and various cognitive markers and biomarkers. | Random effects regression model time-by-treatment effects (group differences): PANSS negative −0.19 (−1.23 to 0.85), p = 0·73 PANSS positive −0.19 (−1.12 to 0.73), p = 0·68 PANSS total −0.58 (−3.75 to 2.59), p = 0·72 CDSS −0.06 (−0.84 to 0.72), p = 0·88 | 0 (0%)—Minocycline 1 (1%)—Placebo | Minocycline did not influence negative or global symptomatology. This result is unlikely to have been confounded by the relatively low baseline negative symptom scores, given the absence of an interaction effect between baseline values and change over time. |

| Antioxidants, Anti-Inflammatory Agents | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study (Country) | Add-On Compound | Daily Dosage | Design/Duration | Sample | Diagnosis | Main Outcomes | Statistical Results | Relapse (%) | Synthesis of Main Findings |

| Berk et al. 2008 [62] (Australia, Switzerland) | N-Acetylcysteine | 2000 mg | 24-week, double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled |

| SCZ, chronic, PANSS total > 55 | PANSS, CGI at baseline 2, 4, 6, 8 and then every 4 weeks till 24 weeks. | ANCOVA between treatment group least squares mean difference at 24 weeks: (95% CI) CGI-S 0.32 (0.05, 0.59), p < 0.05 PANSS Positive 0.5 (1.1, 2.1), p > 0.05 PANSS Negative 1.8 (0.3, 3.3), p < 0.05 PANSS General 2.8 (0.2, 5.4), p < 0.05 PANSS Total 5.9 (1.5, 10.4), p < 0.01 | No information | Patients in the N-Acetylcysteine group presented with moderate improvement compared to placebo in all but the positive symptom dimension at the end of the 24-week trial. |

| Pawełczyk et al. 2016 [63] (Poland) | Omega-3 fatty acids | 2200 mg | 26-week, double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled |

| SCZ, first-episode | PANSS, CDSS, GAF, CGI-S at baseline and at 26 weeks | Mixed-effect models for repeated measures were utilized. Least squares mean differences (i.e., treatment group mean difference—Placebo group mean difference): CDSS: −1.58 (2.7 to 0.47, p < 0.01) PANSS positive: −1.09 (2.41 to 0.23, p > 0.05) PANSS negative: −0.69 (1.97 to 0.6, p > 0.05) PANSS general: −3.14 (5.46 to 0.83, p < 0.01) PANSS total: −4.84 (8.77 to 0.92, p < 0.05) GAF: −0.32 (−0.64 to −0.01, p < 0.05) | No information | The authors reported 6-month improvements in both general psychopathology and global functioning, indicating that omega-3 fatty acids could be a helpful add-on treatment option in maintenance treatment of first-episode patients with antipsychotics. |

| Conus et al. 2018 [64] (Switzerland, USA) | N-Acetylcysteine | 2700 mg | 24-week, double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled |

| SCZ spectrum, early-stage, stable | PANSS, GAF, neurocognitive assessment at baseline and every 4 weeks till 24 weeks. | ANOVA treatment-by-time interaction effect for: PANSS negative β = 0.161, SE = 0.237, p = 0.50 PANSS positive β = 0.176, SE = 0.207, p = 0.39 PANSS general β = 0.598, SE = 0.359, p = 0.09 GAF β = −0.332, SE = 0.515, p = 0.52 | 0 (0%)—N-Acetylcysteine 0 (0%)—Placebo | N-acetylcysteine had no effect on any symptomatology or global functioning measure. Previous results may not have been replicated due to the relatively low mean baseline negative symptoms (lack of room for improvement). |

| Neill et al. 2022 [65] (Australia) | N-Acetylcysteine | 2000 mg | 52-week, double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled |

| SCZ spectrum, treatment resistant | PANSS, cognitive assessment at baseline, 8, 24 and 52 weeks. | Mixed-model repeated measures, time by group effects: PANSS negative F = 0.6, p = 0.616 PANSS positive F = 1.28, p = 0.282 PANSS total F = 0.76, p = 0.521 PANSS depression F = 2.7, p = 0.047 | 0 (0%)—N-Acetylcysteine 0 (0%)—Placebo | N-acetylcysteine offered no clinical benefit in negative, positive or overall symptomatology. A marginally significant effect was reported for depressive symptoms, which could warrant further investigation. |

| Study | Randomization Process | Intervention Adherence | Missing Data | Outcome Measurement | Selective Reporting | Overall Bias |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lenzi et al. 2003 [52] |  |  |  |  |  |  |

| Geoff et al. 2004 [58] |  |  |  |  |  |  |

| Friedman et al. 2005 [44] |  |  |  |  |  |  |

| Sharma et al. 2006 [53] |  |  |  |  |  |  |

| Zoccali et al. 2007 [51] |  |  |  |  |  |  |

| Berk et al. 2008 [62] |  |  |  |  |  |  |

| Levkovitz et al. 2010 [59] |  |  |  |  |  |  |

| Lindenmayer et al. 2010 [54] |  |  |  |  |  |  |

| Chaudhry et al. 2012 [60] |  |  |  |  |  |  |

| Kane et al. 2012 [55] |  |  |  |  |  |  |

| Usall et al. 2014 [45] |  |  |  |  |  |  |

| Barnes et al. 2016 [46] |  |  |  |  |  |  |

| Pawełczyk et al. 2016 [63] |  |  |  |  |  |  |

| Veerman et al. 2016 [56] |  |  |  |  |  |  |

| Kumar et al. 2017 [57] |  |  |  |  |  |  |

| Conus et al. 2018 [64] |  |  |  |  |  |  |

| Deakin et al. 2018 [61] |  |  |  |  |  |  |

| Goff et al. 2019 [47] |  |  |  |  |  |  |

| Neill et al. 2022 [65] |  |  |  |  |  |  |

| Shi et al. 2022 [48] |  |  |  |  |  |  |

| Zhu et al. 2022 [49] |  |  |  |  |  |  |

| Lang et al. 2023 [50] |  |  |  |  |  |  |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Smyrnis, A.; Smyrnis, G.; Smyrnis, N. Add-On Pharmacotherapy in Schizophrenia: Does It Improve Long-Term Outcomes? A Systematic Review. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 7847. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14217847

Smyrnis A, Smyrnis G, Smyrnis N. Add-On Pharmacotherapy in Schizophrenia: Does It Improve Long-Term Outcomes? A Systematic Review. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(21):7847. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14217847

Chicago/Turabian StyleSmyrnis, Alexandros, Giorgos Smyrnis, and Nikolaos Smyrnis. 2025. "Add-On Pharmacotherapy in Schizophrenia: Does It Improve Long-Term Outcomes? A Systematic Review" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 21: 7847. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14217847

APA StyleSmyrnis, A., Smyrnis, G., & Smyrnis, N. (2025). Add-On Pharmacotherapy in Schizophrenia: Does It Improve Long-Term Outcomes? A Systematic Review. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(21), 7847. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14217847