Factors Influencing the Long-Term Survival and Success of Endodontically Treated and Retreated Teeth: An Ambispective Study at an Educational Hospital

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Ethical Approval

2.2. Study Population

2.3. Clinical and Radiographic Assessments

2.4. Reliability of Measurements

2.5. Data Management and Statistical Analysis

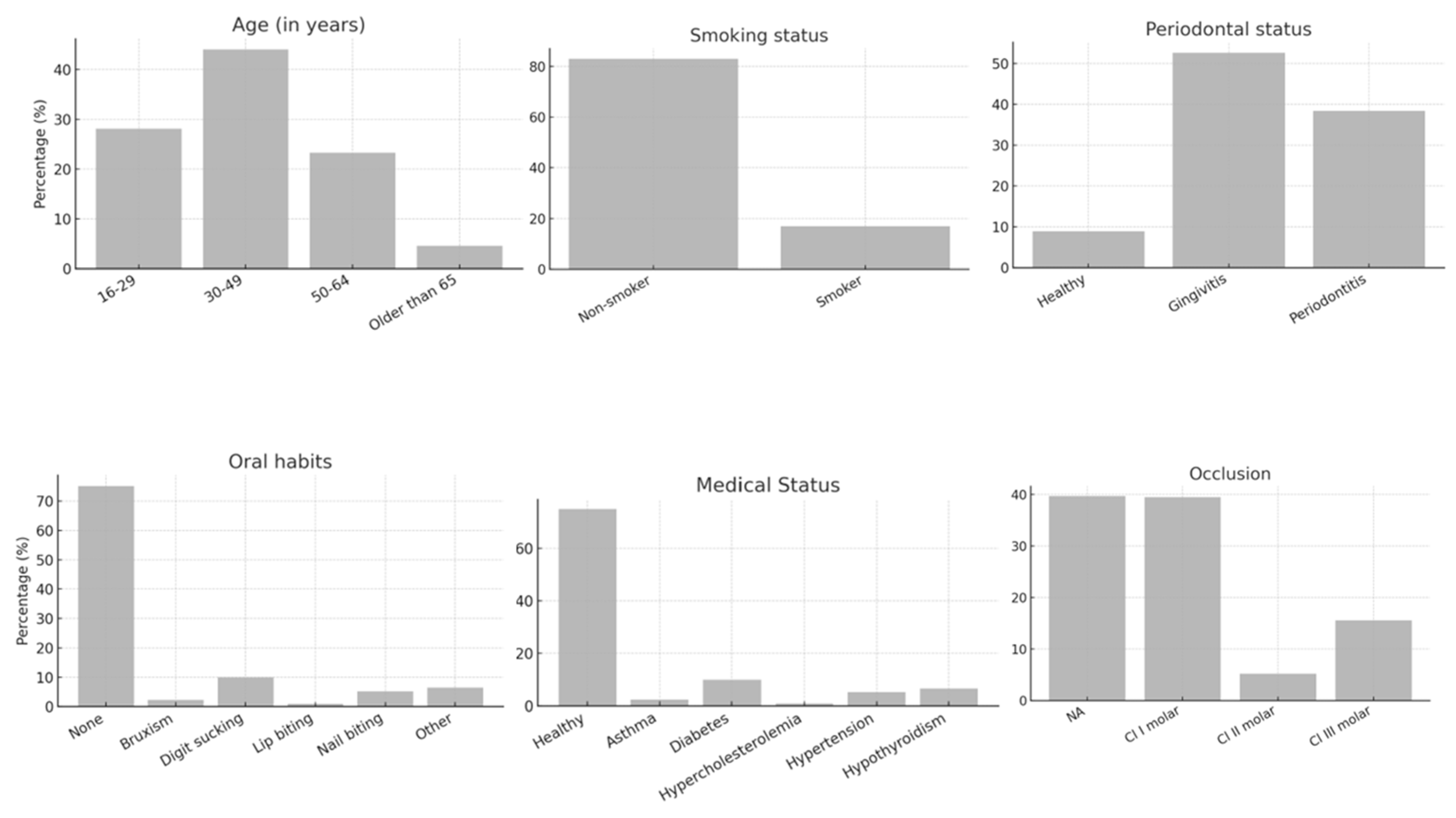

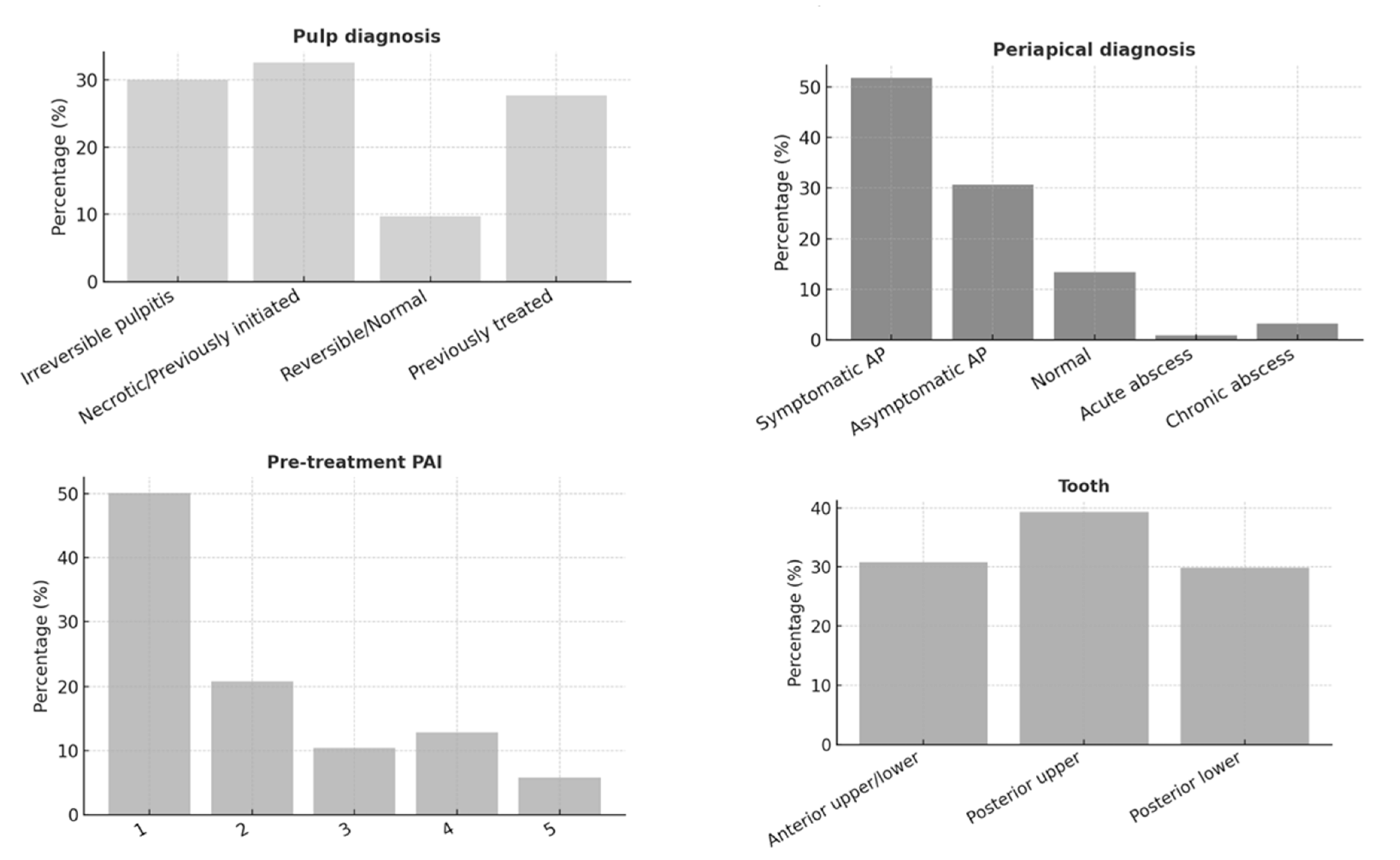

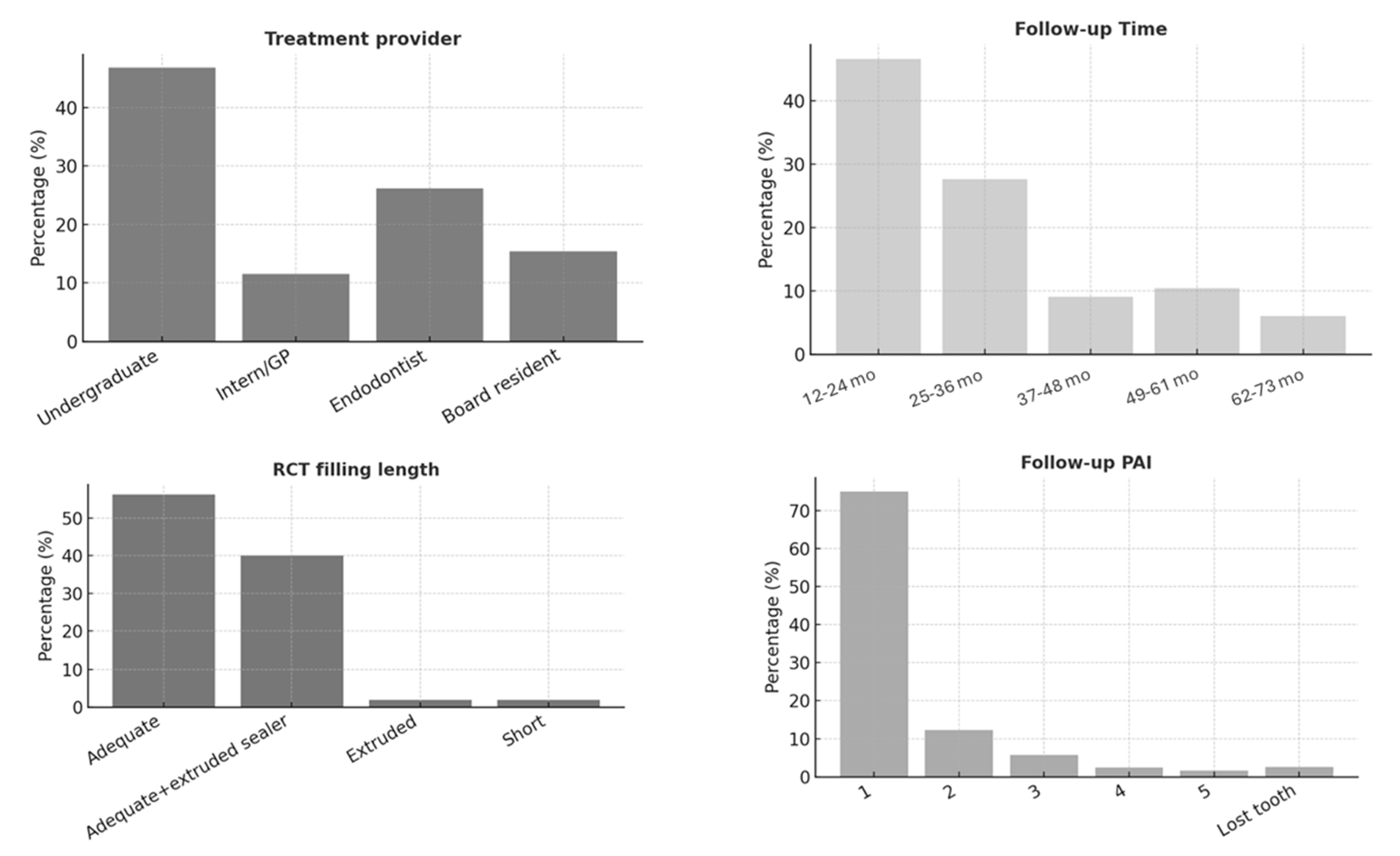

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ETT | Endodontically treated teeth |

| RCT | Root canal treatment |

| PAI | Periapical index |

| PNU | Princess Nourah Bint Abdulrahman University |

| CBCT | Cone-Beam Computed Tomography |

References

- Burns, L.E.; Kim, J.; Wu, Y.; Alzwaideh, R.; McGowan, R.; Sigurdsson, A. Outcomes of Primary Root Canal Therapy: An Updated Systematic Review of Longitudinal Clinical Studies Published between 2003 and 2020. Int. Endod. J. 2022, 55, 714–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ng, Y.-L.; Mann, V.; Rahbaran, S.; Lewsey, J.; Gulabivala, K. Outcome of Primary Root Canal Treatment: Systematic Review of the Literature—Part 1. Effects of Study Characteristics on Probability of Success. Int. Endod. J. 2007, 40, 921–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brochado Martins, J.F.; Georgiou, A.C.; Nunes, P.D.; de Vries, R.; Afreixo, V.M.A.; da Palma, P.J.R.; Shemesh, H. CBCT-Assessed Outcomes and Prognostic Factors of Primary Endodontic Treatment and Retreatment: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Endod. 2025, 51, 687–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, S.; Mor, C. The Success of Endodontic Therapy--Healing and Functionality. J. Calif. Dent. Assoc. 2004, 32, 493–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.-M. Tooth Survival Following Non-Surgical Root Canal Treatment in South Korean Adult Population: A 11-Year Follow-up Study of a Historical Cohort. Eur. Endod. J. 2021, 7, 20–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- López-Valverde, I.; Vignoletti, F.; Vignoletti, G.; Martin, C.; Sanz, M. Long-Term Tooth Survival and Success Following Primary Root Canal Treatment: A 5- to 37-Year Retrospective Observation. Clin. Oral Investig. 2023, 27, 3233–3244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duncan, H.F.; Nagendrababu, V.; El-Karim, I.A.; Dummer, P.M.H. Outcome Measures to Assess the Effectiveness of Endodontic Treatment for Pulpitis and Apical Periodontitis for Use in the Development of European Society of Endodontology (ESE) S3 Level Clinical Practice Guidelines: A Protocol. Int. Endod. J. 2021, 54, 646–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sebring, D.; Buhlin, K.; Norhammar, A.; Rydén, L.; Jonasson, P.; Lund, H.; Kvist, T. Endodontic Inflammatory Disease: A Risk Indicator for a First Myocardial Infarction. Int. Endod. J. 2022, 55, 6–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fransson, H.; Dawson, V. Tooth Survival after Endodontic Treatment. Int. Endod. J. 2023, 56, 140–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sunay, H.; Tanalp, J.; Dikbas, I.; Bayirli, G. Cross-sectional Evaluation of the Periapical Status and Quality of Root Canal Treatment in a Selected Population of Urban Turkish Adults. Int. Endod. J. 2007, 40, 139–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mujawar, A.; Hegde, V.; Srilatha, S. A Retrospective Three-Dimensional Assessment of the Prevalence of Apical Periodontitis and Quality of Root Canal Treatment in Mid-West Indian Population. J. Conserv. Dent. 2021, 24, 192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torabinejad, M.; Corr, R.; Handysides, R.; Shabahang, S. Outcomes of Nonsurgical Retreatment and Endodontic Surgery: A Systematic Review. J. Endod. 2009, 35, 930–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sabeti, M.; Chung, Y.J.; Aghamohammadi, N.; Khansari, A.; Pakzad, R.; Azarpazhooh, A. Outcome of Contemporary Nonsurgical Endodontic Retreatment: A Systematic Review of Randomized Controlled Trials and Cohort Studies. J. Endod. 2024, 50, 414–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siqueira, J.F.J.; Rôças, I.N. Clinical Implications and Microbiology of Bacterial Persistence after Treatment Procedures. J. Endod. 2008, 34, 1291–1301.e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vieira, A.R.; Pacheco-Yanes, J.; Gazzaneo, I.D.; Neves, M.A.S.; Siqueira, J.F.; Gonçalves, L.S. Factors Influencing the Outcome of Nonsurgical Root Canal Treatment and Retreatment: A Retrospective Study. Aust. Endod. J. 2024, 50, 245–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, Y.-L.; Mann, V.; Gulabivala, K. A Prospective Study of the Factors Affecting Outcomes of Nonsurgical Root Canal Treatment: Part 1: Periapical Health. Int. Endod. J. 2011, 44, 583–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sabeti, M.A.; Karimpourtalebi, N.; Shahravan, A.; Dianat, O. Clinical and Radiographic Failure of Nonsurgical Endodontic Treatment and Retreatment Using Single-Cone Technique With Calcium Silicate-Based Sealers: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Endod. 2024, 50, 735–746.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Göransson, H.; Lougui, T.; Castman, L.; Jansson, L. Survival of Root Filled Teeth in General Dentistry in a Swedish County: A 6-Year Follow-up Study. Acta Odontol. Scand. 2021, 79, 396–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadaf, D. Survival Rates of Endodontically Treated Teeth After Placement of Definitive Coronal Restoration: 8-Year Retrospective Study. Ther. Clin. Risk Manag. 2020, 16, 125–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, Y.-L.; Mann, V.; Gulabivala, K. A Prospective Study of the Factors Affecting Outcomes of Non-Surgical Root Canal Treatment: Part 2: Tooth Survival. Int. Endod. J. 2011, 44, 610–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ray, H.A.; Trope, M. Periapical Status of Endodontically Treated Teeth in Relation to the Technical Quality of the Root Filling and the Coronal Restoration. Int. Endod. J. 1995, 28, 12–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kayahan, M.B.; Malkondu, Ö.; Canpolat, C.; Kaptan, F.; Bayırlı, G.; Kazazoglu, E. Periapical Health Related to the Type of Coronal Restorations and Quality of Root Canal Fillings in a Turkish Subpopulation. Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Pathol. Oral Radiol. Endodontology 2008, 105, e58–e62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavares, P.B.L.; Bonte, E.; Boukpessi, T.; Siqueira, J.F.; Lasfargues, J.-J. Prevalence of Apical Periodontitis in Root Canal–Treated Teeth From an Urban French Population: Influence of the Quality of Root Canal Fillings and Coronal Restorations. J. Endod. 2009, 35, 810–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hommez, G.M.G.; Coppens, C.R.M.; De Moor, R.J.G. Periapical Health Related to the Quality of Coronal Restorations and Root Fillings. Int. Endod. J. 2002, 35, 680–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chugal, N.M.; Clive, J.M.; Spångberg, L.S.W. Endodontic Treatment Outcome: Effect of the Permanent Restoration. Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Pathol. Oral Radiol. Endodontology 2007, 104, 576–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ricucci, D.; Russo, J.; Rutberg, M.; Burleson, J.A.; Spångberg, L.S.W. A Prospective Cohort Study of Endodontic Treatments of 1369 Root Canals: Results after 5 Years. Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Pathol. Oral Radiol. Endodontology 2011, 112, 825–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ørstavik, D. Time-Course and Risk Analyses of the Development and Healing of Chronic Apical Periodontitis in Man. Int. Endod. J. 1996, 29, 150–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrieshi-Nusair, K.; Al-Omari, M.; Al-Hiyasat, A. Radiographic Technical Quality of Root Canal Treatment Performed by Dental Students at the Dental Teaching Center in Jordan. J. Dent. 2004, 32, 301–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balto, H.; Al Khalifah, S.; Al Mugairin, S.; Al Deeb, M.; Al-Madi, E. Technical Quality of Root Fillings Performed by Undergraduate Students in Saudi Arabia. Int. Endod. J. 2010, 43, 292–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández, R.; Cardona, J.A.; Cadavid, D.; Álvarez, L.G.; Restrepo, F.A. Survival of Endodontically Treated Roots/Teeth Based on Periapical Health and Retention: A 10-Year Retrospective Cohort Study. J. Endod. 2017, 43, 2001–2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rödig, T.; Vu, M.-T.; Kanzow, P.; Haupt, F. Long-Term Survival of Endodontically Treated Teeth: A Retrospective Analysis of Predictive Factors at a German Dental School. J. Dent. 2025, 156, 105662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almufleh, L.S. The Outcomes of Nonsurgical Root Canal Treatment and Retreatment Assessed by CBCT: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Saudi Dent. J. 2025, 37, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Rocha, J.G.; Lena, I.M.; Trindade, J.L.; Liedke, G.S.; Morgental, R.D.; Bier, C.A.S. Outcome of Endodontic Treatments Performed by Brazilian Undergraduate Students: 3- to 8-Year Follow Up. Restor. Dent. Endod. 2022, 47, e34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azarpazhooh, A.; Sgro, A.; Cardoso, E.; Elbarbary, M.; Laghapour Lighvan, N.; Badewy, R.; Malkhassian, G.; Jafarzadeh, H.; Bakhtiar, H.; Khazaei, S.; et al. A Scoping Review of 4 Decades of Outcomes in Nonsurgical Root Canal Treatment, Nonsurgical Retreatment, and Apexification Studies—Part 2: Outcome Measures. J. Endod. 2022, 48, 29–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chien, P.Y.-H.; Hosseinpour, S.; Peters, O.A.; Peters, C.I. Outcomes of Root Canal Treatment Performed by Undergraduate Students: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Int. Endod. J. 2025, 304–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahreis, M.; Soliman, S.; Schubert, A.; Connert, T.; Schlagenhauf, U.; Krastl, G.; Krug, R. Outcome of Non-surgical Root Canal Treatment Related to Periodontitis and Chronic Disease Medication among Adults in Age Group of 60 Years or More. Gerodontology 2019, 36, 267–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gulabivala, K.; Ng, Y.L. Factors That Affect the Outcomes of Root Canal Treatment and Retreatment—A Reframing of the Principles. Int. Endod. J. 2023, 56, 82–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, Y.-L.; Mann, V.; Rahbaran, S.; Lewsey, J.; Gulabivala, K. Outcome of Primary Root Canal Treatment: Systematic Review of the Literature—Part 2. Influence of Clinical Factors. Int. Endod. J. 2008, 41, 6–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonzar, F.; Kalemaj, Z.; Fabian Fonzar, R.; Buti, J.; Buttolo, P.; Forner Navarro, L.; Fonzar, A.; Esposito, M. The Prognosis of Root Canal Therapy: A 20-Year Follow-Up Ambispective Cohort Study on 411 Patients with 1169 Endodontically Treated Teeth. Clin. Trials Dent. 2021, 3, 5–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalighinejad, N.; Aminoshariae, A.; Kulild, J.C.; Wang, J.; Mickel, A. The Influence of Periodontal Status on Endodontically Treated Teeth: 9-Year Survival Analysis. J. Endod. 2017, 43, 1781–1785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, Y.; Choi, M.; Wang, Y.-B.; Lee, S.-M.; Yang, M.; Wu, B.H.; Fiorellini, J. Risk Factors Associated with the Survival of Endodontically Treated Teeth. J. Am. Dent. Assoc. 2024, 155, 39–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maslamani, M.; Khalaf, M.; Mitra, A. Association of Quality of Coronal Filling with the Outcome of Endodontic Treatment: A Follow-up Study. Dent. J. 2017, 5, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stenhagen, S.; Skeie, H.; Bårdsen, A.; Laegreid, T. Influence of the Coronal Restoration on the Outcome of Endodontically Treated Teeth. Acta Odontol. Scand. 2020, 78, 81–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zamparini, F.; Spinelli, A.; Lenzi, J.; Peters, O.A.; Gandolfi, M.G.; Prati, C. Retreatment or Replacement of Previous Endodontically Treated Premolars with Recurrent Apical Periodontitis? An 8-Year Historical Cohort Study. Clin. Oral Investig. 2025, 29, 181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Guerrero, C.; Delgado-Rodríguez, C.E.; Molano-González, N.; Pineda-Velandia, G.A.; Marín-Zuluaga, D.J.; Leal-Fernandez, M.C.; Gutmann, J.L. Predicting the Outcome of Initial Non-Surgical Endodontic Procedures by Periapical Status and Quality of Root Canal Filling: A Cohort Study. Odontology 2020, 108, 697–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehta, D.; Coleman, A.; Lessani, M. Success and Failure of Endodontic Treatment: Predictability, Complications, Challenges and Maintenance. Br. Dent. J. 2025, 238, 527–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craveiro, M.A.; Fontana, C.E.; de Martin, A.S.; Bueno, C.E.D.S. Influence of Coronal Restoration and Root Canal Filling Quality on Periapical Status: Clinical and Radiographic Evaluation. J. Endod. 2015, 41, 836–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farzaneh, M.; Abitbol, S.; Lawrence, H.P.; Friedman, S. Treatment Outcome in Endodontics—The Toronto Study. Phase II: Initial Treatment. J. Endod. 2004, 30, 302–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aminoshariae, A.; Kulild, J.C. The Impact of Sealer Extrusion on Endodontic Outcome: A Systematic Review with Meta-analysis. Aust. Endod. J. 2020, 46, 123–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Kuijper, M.C.F.M.; Cune, M.S.; Özcan, M.; Gresnigt, M.M.M. Clinical Performance of Direct Composite Resin versus Indirect Restorations on Endodontically Treated Posterior Teeth: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2023, 130, 295–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gillen, B.M.; Looney, S.W.; Gu, L.-S.; Loushine, B.A.; Weller, R.N.; Loushine, R.J.; Pashley, D.H.; Tay, F.R. Impact of the Quality of Coronal Restoration versus the Quality of Root Canal Fillings on Success of Root Canal Treatment: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Endod. 2011, 37, 895–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frisk, F.; Hugosson, A.; Kvist, T. Is Apical Periodontitis in Root Filled Teeth Associated with the Type of Restoration? Acta Odontol. Scand. 2015, 73, 169–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, S.; Nilker, V.; Telikapalli, M.; Gala, K. Incidence of Endodontic Failure Cases in the Department of Conservative Dentistry and Endodontics, DY Patil School of Dentistry, Navi Mumbai. Cureus 2023, 15, e38841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pontoriero, D.I.K.; Grandini, S.; Spagnuolo, G.; Discepoli, N.; Benedicenti, S.; Maccagnola, V.; Mosca, A.; Ferrari Cagidiaco, E.; Ferrari, M. Clinical Outcomes of Endodontic Treatments and Restorations with and without Posts Up to 18 Years. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stueland, H.; Ørstavik, D.; Handal, T. Treatment Outcome of Surgical and Non-surgical Endodontic Retreatment of Teeth with Apical Periodontitis. Int. Endod. J. 2023, 56, 686–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Quadros, I.; Gomes, B.P.F.A.; Zaia, A.A.; Ferraz, C.C.R.; Souza-Filho, F.J. Evaluation of Endodontic Treatments Performed by Students in a Brazilian Dental School. J. Dent. Educ. 2005, 69, 1161–1170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mareschi, P.; Taschieri, S.; Corbella, S. Long-Term Follow-Up of Nonsurgical Endodontic Treatments Performed by One Specialist: A Retrospective Cohort Study about Tooth Survival and Treatment Success. Int. J. Dent. 2020, 2020, 8855612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Influencing Factors | Success N = 374 (%) | Failure N = 87 (%) | Total N = 461 (%) | p Value | |

| Follow-up Time | 12–24 months (median: 16.4 months) | 205 (82.66) | 43 (17.33) | 248 (53.79) | |

| 25–36 months (median: 25 months) | 90 (81.08) | 21 (18.92) | 111 (24) | ||

| 37–48 months (median: 37 months) | 29 (82.86) | 6 (17.14) | 35 (7.59) | ||

| 49–60 months (median: 57 months) | 32 (65.31) | 17 (34.69) | 49 (10.62) | ||

| 61–73 months (median: 61 months) | 18 (100.00) | 0 (0.00) | 18 (3.9) | ||

| Treatment provider | Undergraduate student | 178 (82.49) | 38 (17.51) | 216 (46.85) | 0.8427 |

| Intern/GP | 41 (77.36) | 12 (22.64) | 53 (11.49) | ||

| Endodontist | 98 (80.99) | 23 (19) | 121 (26.24) | ||

| Board resident | 57 (80.28) | 14 (19.72) | 71 (15.4) | ||

| Periapical preoperative status | 1 | 201 (87.07) | 30 (12.93) | 231 (50.11) | 0.0010 * |

| 2 | 78 (81.25) | 18 (18.75) | 96 (20.82) | ||

| 3 | 36 (75.00) | 12 (25.00) | 48 (10.41) | ||

| 4 | 43 (71.67) | 16 (28.33) | 59 (12.79) | ||

| 5 | 16 (59.26) | 11 (40.74) | 27 (5.85) | ||

| RCT filling length | Adequate | 218 (83.85) | 41 (16.15) | 259 (56.18) | 0.1097 |

| Adequate with extruded sealer | 144 (78.38) | 40 (21.62) | 184 (39.91) | ||

| Extruded | 7 (77.78) | 2 (22.22) | 9 (1.94) | ||

| Short | 5 (55.56) | 4 (44.44) | 9 (1.94) | ||

| RCT filling density | Adequate | 368 (81.46) | 83 (18.54) | 451 (97.83) | 0.0631 |

| Inadequate apical third | 4 (80.00) | 1 (20.00) | 5 (1.08) | ||

| Inadequate middle/coronal third | 2 (40.00) | 3 (60.00) | 5 (1.08) | ||

| Restoration material | Permanent | 240 (86.33) | 38 (13.67) | 278 (60.3) | <0.0001 * |

| Interim | 134 (78.03) | 37 (21.97) | 171 (37.0) | ||

| Lost tooth | 0 (0.00) | 12 (100.00) | 12 (2.6) | ||

| Restoration material type | GIC | 130 (78.44) | 35 (21.56) | 165 (35.79) | <0.0001 * |

| Resin composite | 29 (72.50) | 11 (27.50) | 40 (8.67) | ||

| Indirect restoration/Crown | 215 (88.11) | 29 (11.89) | 244 (52.92) | ||

| Coronal restoration provider | Undergraduate student | 173 (83.25) | 35 (16.75) | 208 (45.11) | <0.0001 * |

| Dental intern/GP | 56 (84.85) | 10 (15.15) | 66 (14.31) | ||

| Endodontist | 32 (80.00) | 7 (20.00) | 39 (8.46) | ||

| Board resident | 61 (81.33) | 14 (18.67) | 75 (16.26) | ||

| Operative dentist/Prosthodontist | 51 (85.00) | 9 (15.00) | 60 (13) | ||

| Lost tooth | 1 (7.69) | 12 (92.31) | 13 (2.82) | ||

| Restoration status assessment | Broken/lost | 19 (52.78) | 17 (47.22) | 36 (7.80) | <0.0001 * |

| Adequate | 311 (84.78) | 55 (15.22) | 366 (79.39) | ||

| inadequate | 44 (74.58) | 15 (25.42) | 59 (12.79) | ||

| Post | Yes | 212 (87.97) | 29 (12.03) | 241 (52.27) | <0.0001 * |

| No | 162 (77.62) | 46 (22.38) | 208 (45.11) | ||

| Lost tooth | 0 (0.00) | 12 (100.00) | 12 (2.6) | ||

| Post type | Fiber post | 135 (89.40) | 16 (10.60) | 151 (32.75) | <0.0001 * |

| Cast post | 80 (86.02) | 13 (13.98) | 93 (20.17) | ||

| Lost tooth | 0 (0.00) | 12 (100.00) | 12 (2.6) | ||

| No post | 159 (77.29) | 46 (22.71) | 205 (44.47) | ||

| Pulp diagnosis | Irreversible | 109 (79.14) | 29 (20.86) | 138 (29.93) | 0.7383 |

| Necrotic/Previously initiated | 122 (80.79) | 28 (19.21) | 150 (32.52) | ||

| Reversible/Normal | 39 (86.67) | 6 (13.33) | 45 (9.76) | ||

| Previously treated | 104 (81.25) | 24 (18.75) | 128 (27.76) | ||

| Periapical diagnosis | Symptomatic Apical Periodontitis | 191 (79.92) | 48 (20.08) | 239 (51.84) | 0.2583 |

| Asymptomatic Apical Periodontitis | 118 (83.80) | 23 (16.20) | 141 (30.58) | ||

| Normal | 52 (83.87) | 10 (16.13) | 62 (13.45) | ||

| Acute Apical Abscess | 2 (50.00) | 2 (50.00) | 4 (0.86) | ||

| Chronic Apical Abscess | 11 (68.75) | 4 (31.25) | 15 (3.25) | ||

| Follow-Up | Sig. | Exp (B) | 95% CI. for Exp (B) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | |||

| 0.998 | 292,825,981.6 | 0.000 | . | |

| Treatment provider | 0.627 | 1.505 | 0.290 | 7.819 |

| Periapical Index pre-op status | 0.001 * | 3.802 | 1.714 | 8.434 |

| RCT filling length | 0.514 | 1.219 | 0.672 | 2.213 |

| RCT filling density | 0.020 * | 9.410 | 1.418 | 62.428 |

| Restoration material type | 0.686 | 0.767 | 0.212 | 2.777 |

| Coronal restoration provider | 0.284 | 1.897 | 0.588 | 6.125 |

| Restoration status assessment | 0.018 * | 0.292 | 0.105 | 0.811 |

| Post | 0.999 | 0.000 | 0.000 | . |

| Post type | 0.696 | 1.194 | 0.490 | 2.909 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Barakat, R.; Almohareb, R.; Alsawah, G.; Busuhail, H.; Alshihri, S.A.; Alrashid, G.T.; Alotaibi, G.Y.; Hebbal, M. Factors Influencing the Long-Term Survival and Success of Endodontically Treated and Retreated Teeth: An Ambispective Study at an Educational Hospital. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 7826. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14217826

Barakat R, Almohareb R, Alsawah G, Busuhail H, Alshihri SA, Alrashid GT, Alotaibi GY, Hebbal M. Factors Influencing the Long-Term Survival and Success of Endodontically Treated and Retreated Teeth: An Ambispective Study at an Educational Hospital. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(21):7826. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14217826

Chicago/Turabian StyleBarakat, Reem, Rahaf Almohareb, Ghaliah Alsawah, Hadeel Busuhail, Shahad A. Alshihri, Ghadah T. Alrashid, Ghadeer Y. Alotaibi, and Mamata Hebbal. 2025. "Factors Influencing the Long-Term Survival and Success of Endodontically Treated and Retreated Teeth: An Ambispective Study at an Educational Hospital" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 21: 7826. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14217826

APA StyleBarakat, R., Almohareb, R., Alsawah, G., Busuhail, H., Alshihri, S. A., Alrashid, G. T., Alotaibi, G. Y., & Hebbal, M. (2025). Factors Influencing the Long-Term Survival and Success of Endodontically Treated and Retreated Teeth: An Ambispective Study at an Educational Hospital. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(21), 7826. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14217826