Long-Term and Heavy Smoking as a Risk Factor for Lumbar Spinal Stenosis: Evidence from a Large-Scale, Nationwide Population-Based Cohort

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

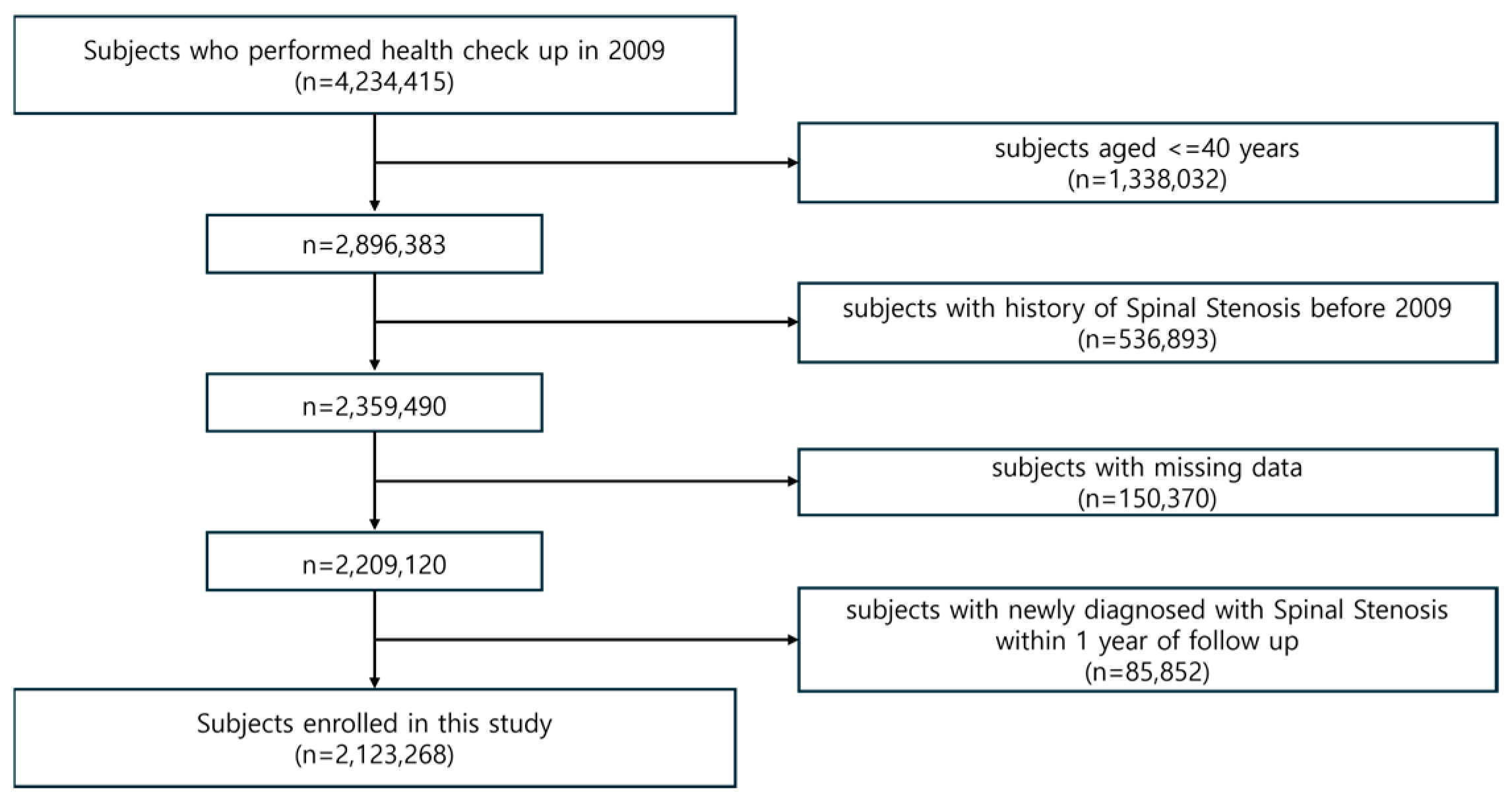

2.1. Data Source and Study Population

2.2. Ethics

2.3. Health Screening Variables and Definition of Comorbidities

- Hypertension: Presence of ICD-10 codes I10–I13 or I15 along with prescription of antihypertensive medication, or a systolic blood pressure ≥ 140 mmHg or diastolic blood pressure ≥ 90 mmHg at screening.

- Diabetes mellitus: Presence of ICD-10 codes E11–E14 along with prescription of antidiabetic medication, or a fasting glucose level ≥ 126 mg/dL.

- Dyslipidemia: Presence of ICD-10 code E78, prescription of lipid-lowering agents, or a total cholesterol level ≥ 240 mg/dL.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

2.4.1. Basic Statistical Analysis

2.4.2. Sex- and Age-Stratified Analyses

2.4.3. Multivariable Subgroup Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Baseline Characteristics of the Study Population

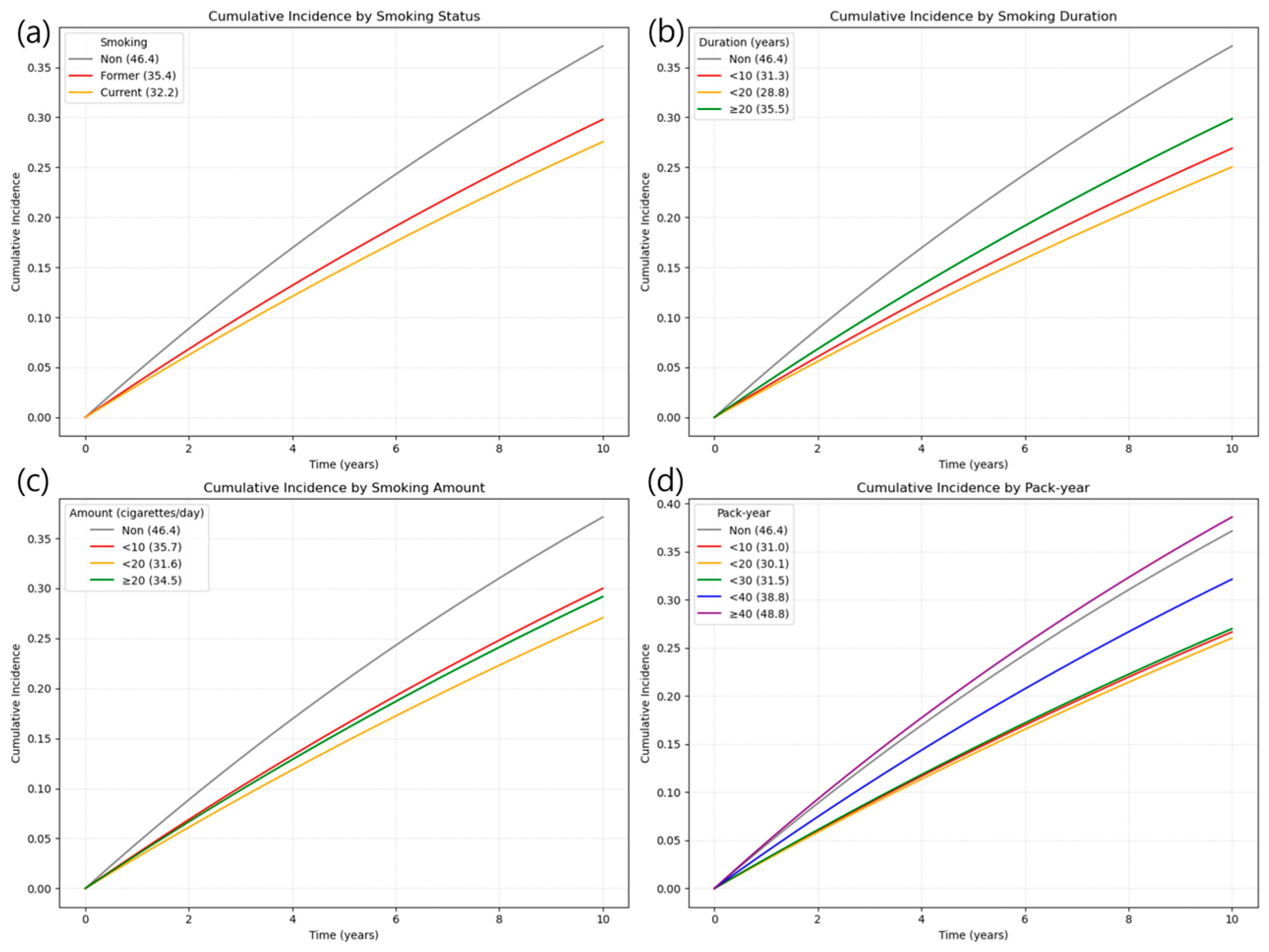

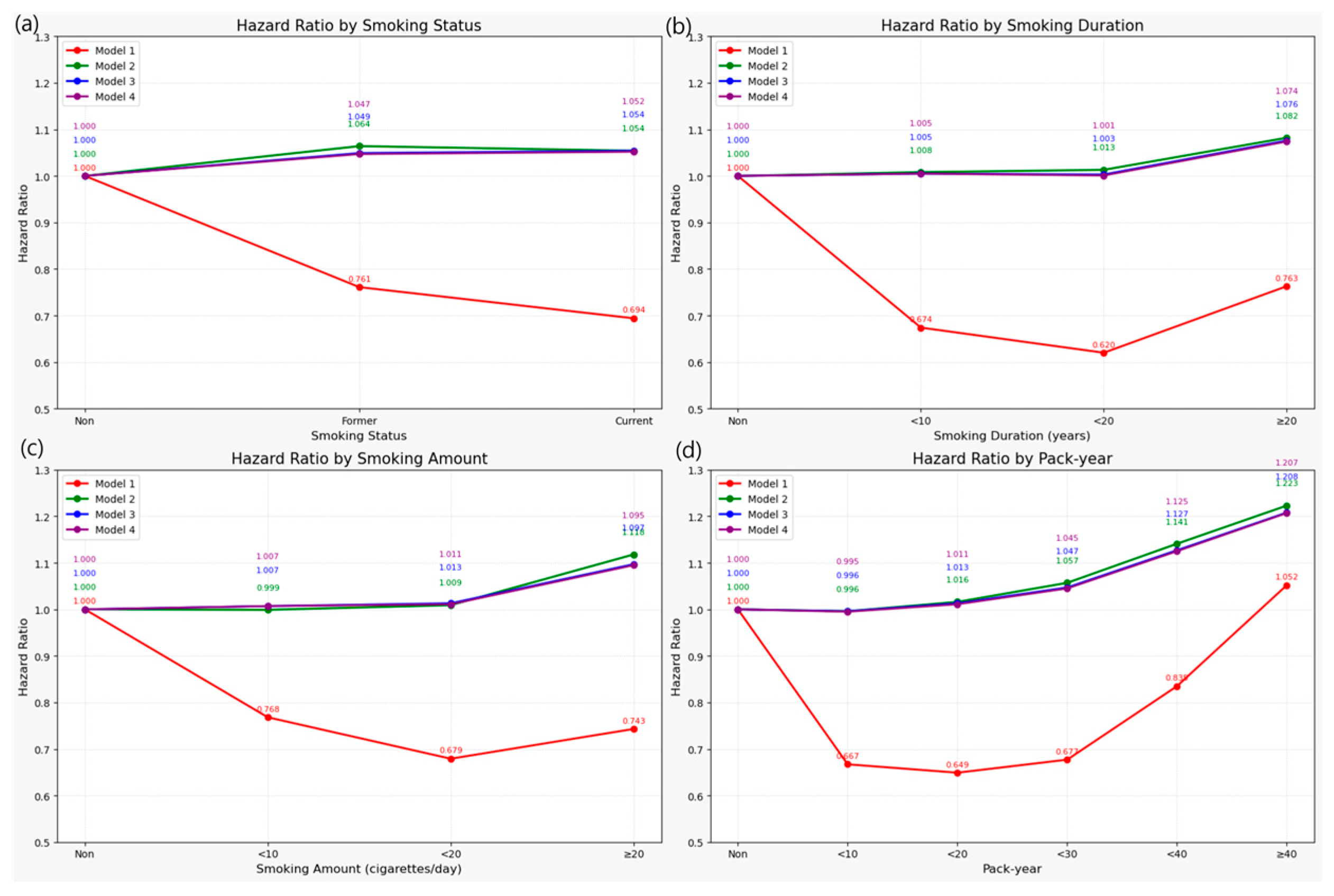

3.2. Association Between Smoking and Risk of LSS

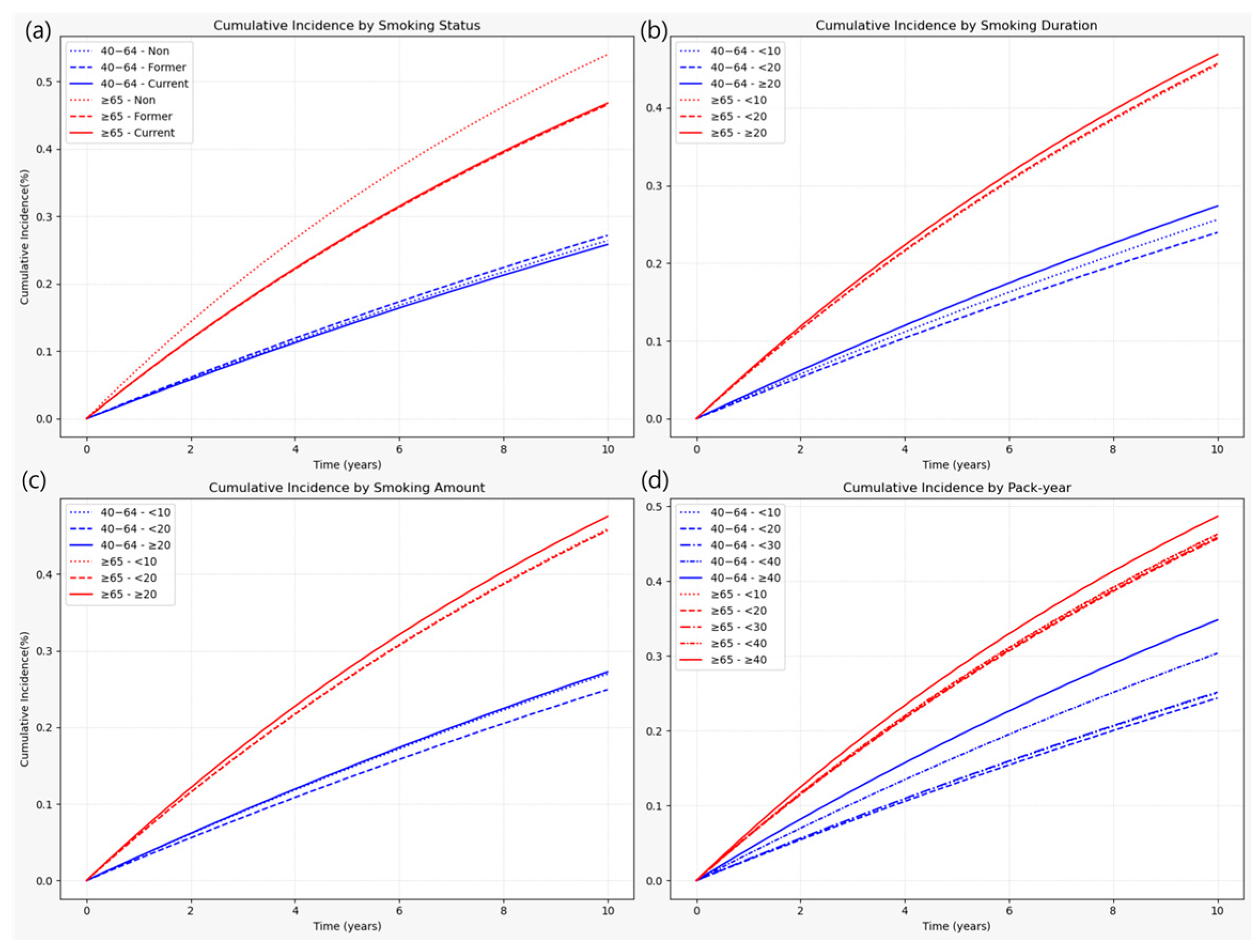

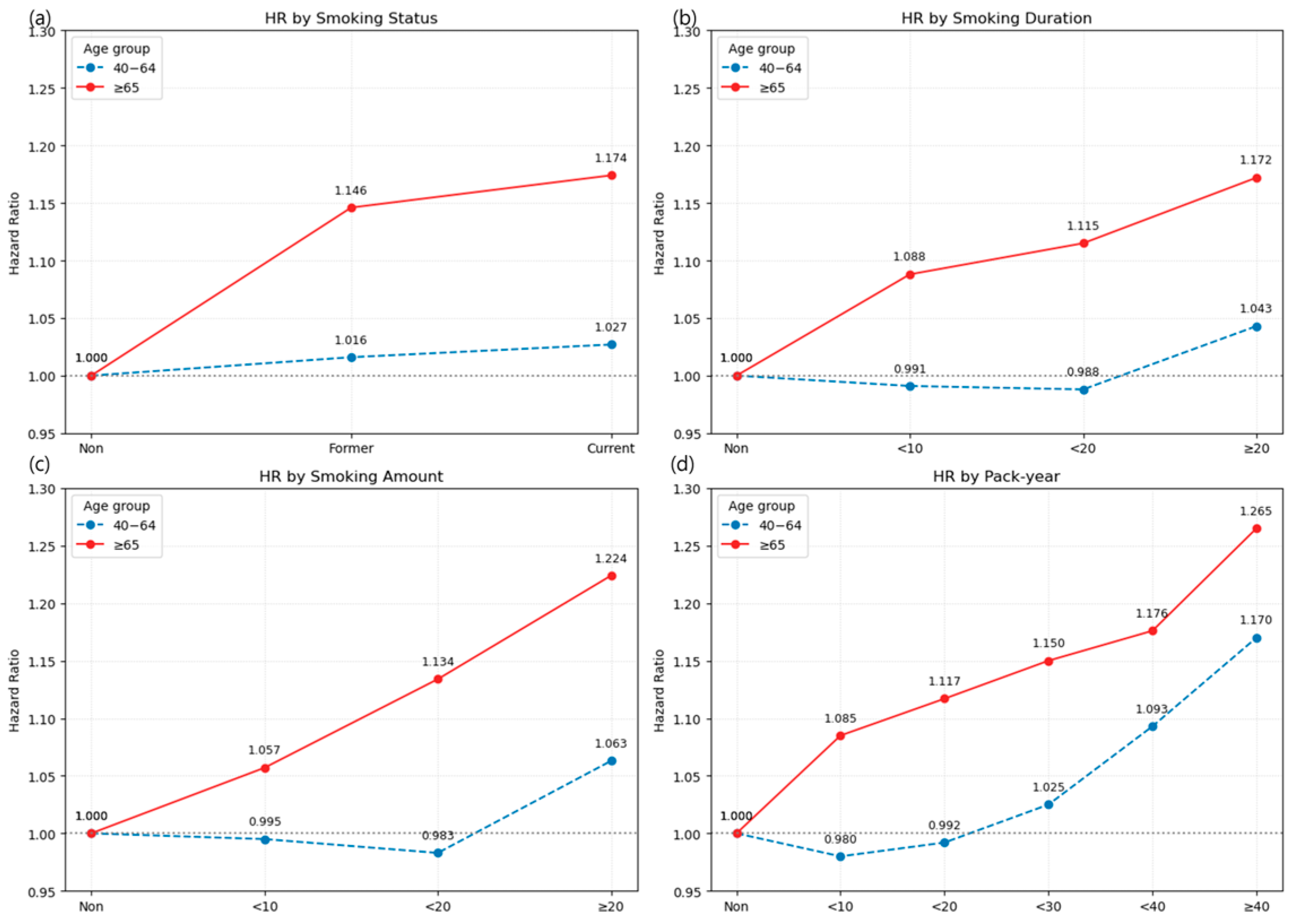

3.2.1. Heterogeneity of Smoking Risk by Age

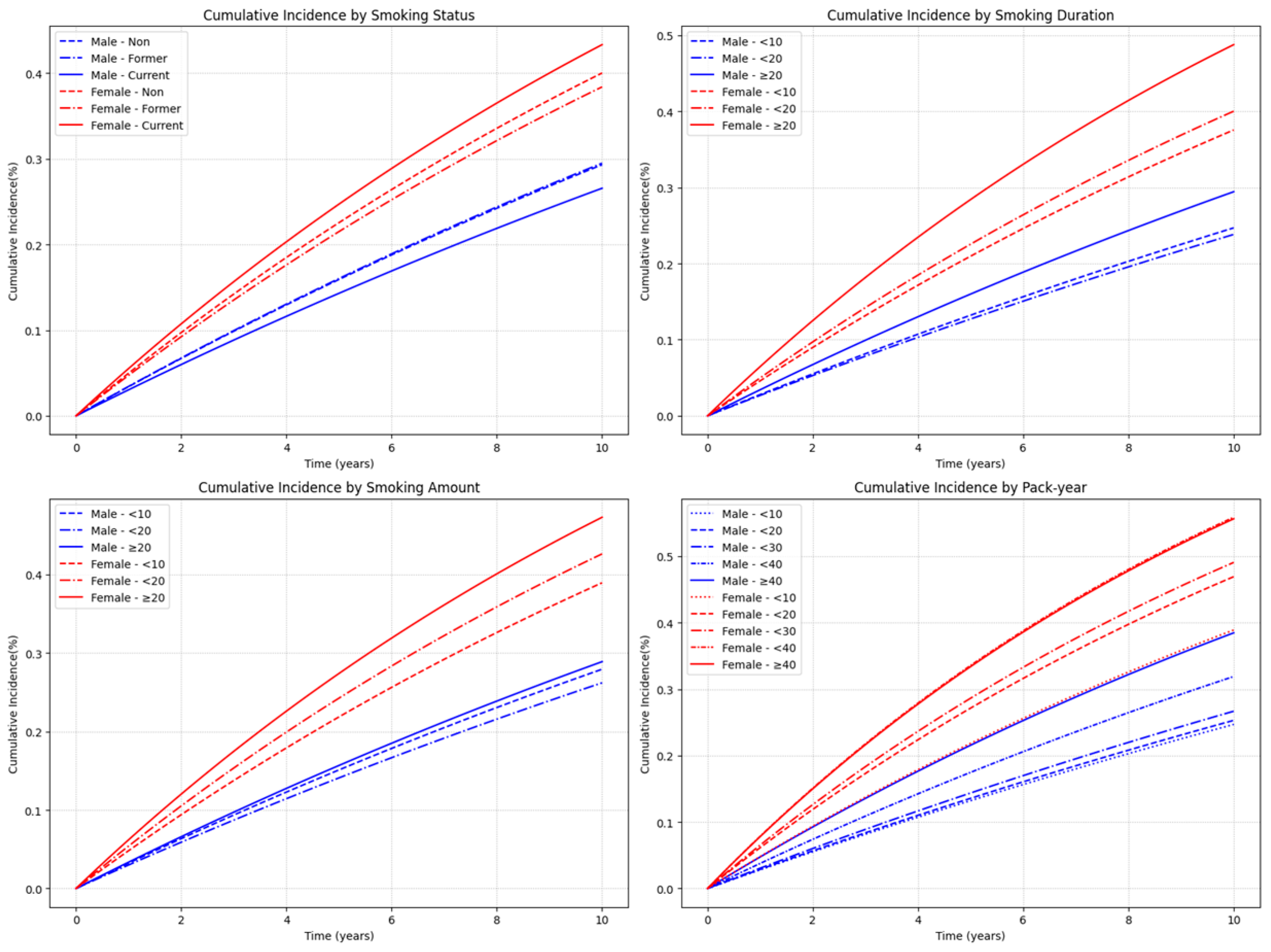

3.2.2. Heterogeneity of Smoking Risk by Sex

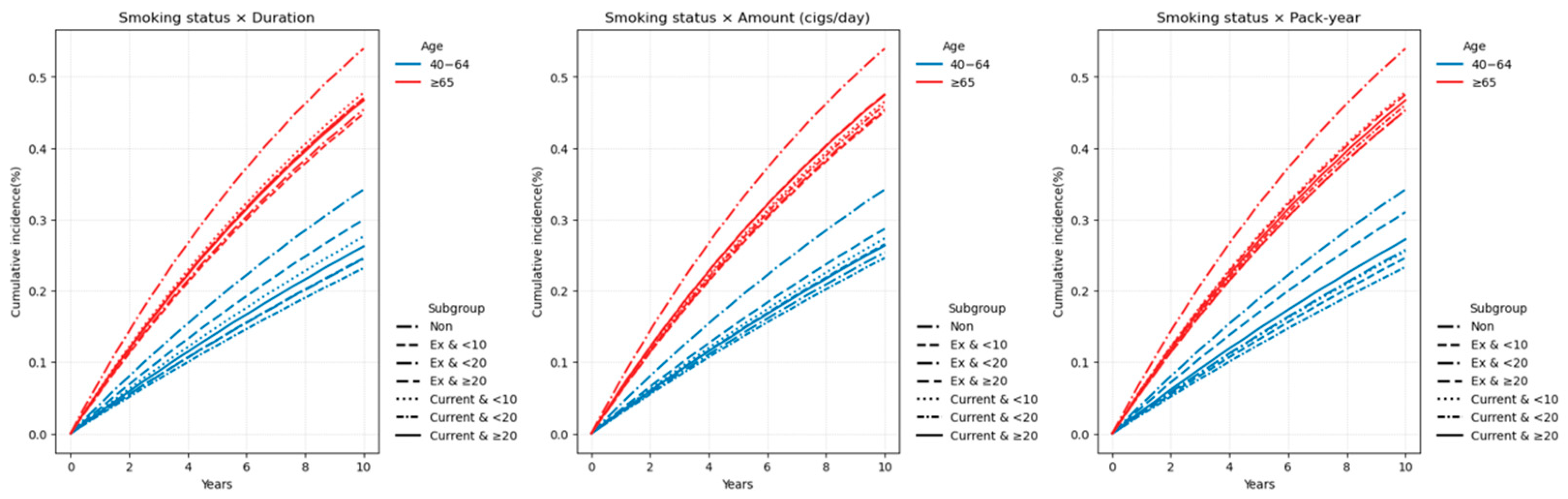

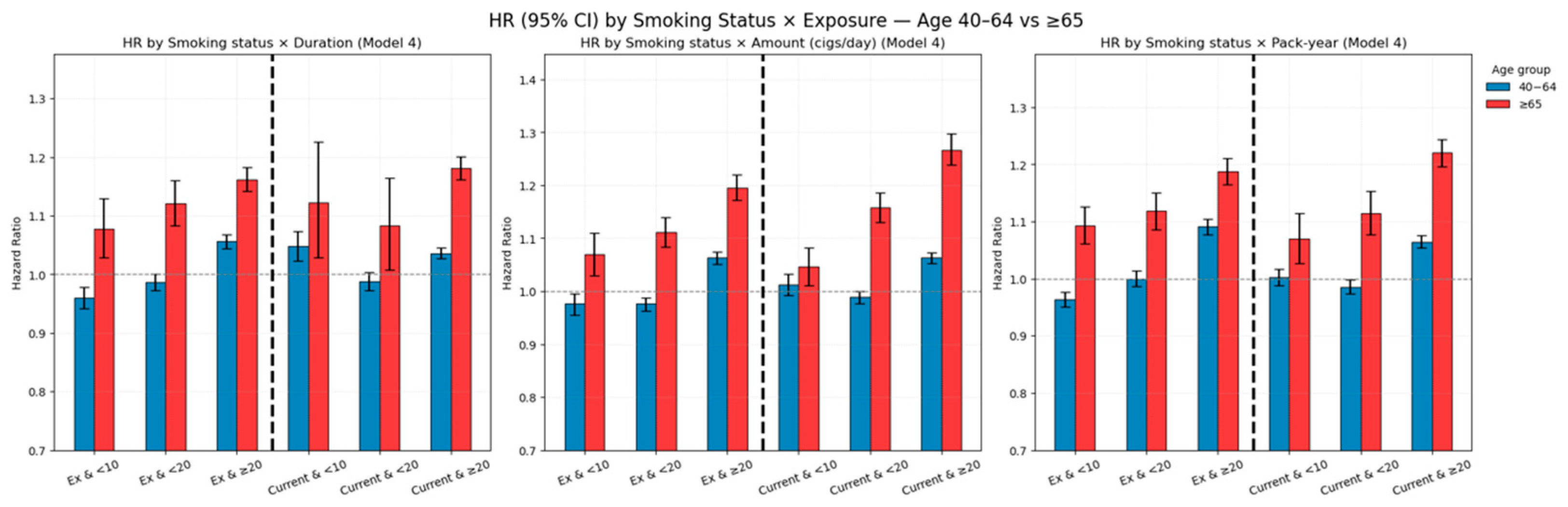

3.3. Combined Effect of Smoking Cessation and Cumulative Smoking Burden

3.3.1. Age-Stratified Effects of Combined Smoking Burden and Cessation

3.3.2. Sex-Stratified Effects of Combined Smoking Burden and Cessation

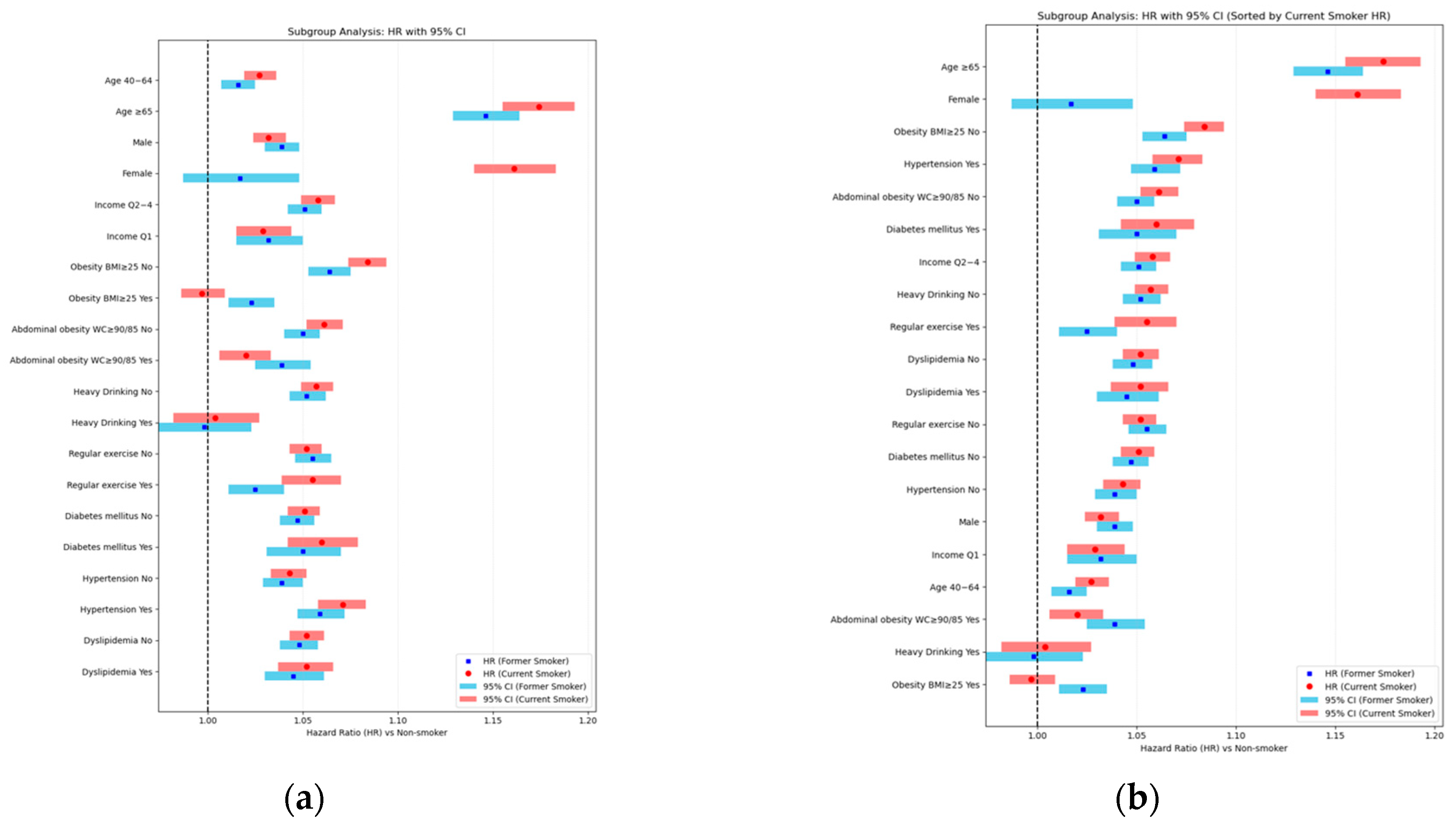

3.4. Association of Smoking with LSS Risk by Subgroups and Interaction Analysis

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Appendix A.1. Association Between Smoking and LSS by Dichotomized Age Groups (<65 vs. ≥65 Years)

| Age 40–64 Years | Age ≥65 Years | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Event | Duration | IR, per 1000 PY | Model 4 | N | Event | Duration | IR, per 1000 PY | Model 4 | |

| Smoking | ||||||||||

| None | 1,099,107 | 384,974 | 9,190,028.6 | 41.8904 | 1 (Ref.) | 207,142 | 103,761 | 1,337,361.64 | 77.5863 | 1 (Ref.) |

| Former | 289,693 | 80,465 | 2,537,191.47 | 31.7142 | 1.016 (1.007, 1.025) | 50,222 | 21,293 | 340,030.13 | 62.6209 | 1.146 (1.129, 1.164) |

| Current | 432,328 | 113,120 | 3,787,142.02 | 29.8695 | 1.027 (1.019, 1.036) | 44,776 | 18,296 | 290,294.51 | 63.0256 | 1.174 (1.155, 1.193) |

| Smoking duration | ||||||||||

| None | 1,099,107 | 384,974 | 9,190,028.6 | 41.8904 | 1 (Ref.) | 207,142 | 103,761 | 1,337,361.64 | 77.5863 | 1 (Ref.) |

| <10 | 70,412 | 18,446 | 623,498.34 | 29.5847 | 0.991 (0.976, 1.006) | 5337 | 2249 | 37,092.96 | 60.6315 | 1.088 (1.043, 1.135) |

| <20 | 172,790 | 42,370 | 1,546,564.87 | 27.3962 | 0.988 (0.977, 0.999) | 9814 | 4169 | 68,297.53 | 61.0417 | 1.115 (1.080, 1.150) |

| ≥20 | 478,819 | 132,769 | 4,154,270.29 | 31.9596 | 1.043 (1.034, 1.051) | 79,847 | 33,171 | 524,934.15 | 63.1908 | 1.172 (1.157, 1.188) |

| Smoking amount | ||||||||||

| None | 1,099,107 | 384,974 | 9,190,028.6 | 41.8904 | 1 (Ref.) | 207,142 | 103,761 | 1,337,361.64 | 77.5863 | 1 (Ref.) |

| <10 | 71,438 | 19,640 | 624,696.7 | 31.4393 | 0.995 (0.980, 1.010) | 15,638 | 6292 | 102,376.17 | 61.4596 | 1.057 (1.030, 1.084) |

| <20 | 266,882 | 67,873 | 2,365,595.98 | 28.6917 | 0.983 (0.974, 0.993) | 34,132 | 14,042 | 229,655.78 | 61.1437 | 1.134 (1.114, 1.155) |

| ≥20 | 383,701 | 106,072 | 3,334,040.82 | 31.8148 | 1.063 (1.054, 1.072) | 45,228 | 19,255 | 298,292.7 | 64.5507 | 1.224 (1.204, 1.244) |

| Pack-year | ||||||||||

| None | 1,099,107 | 384,974 | 9,190,028.6 | 41.8904 | 1 (Ref.) | 207,142 | 103,761 | 1,337,361.64 | 77.5863 | 1 (Ref.) |

| <10 | 178,284 | 45,617 | 1,583,458.76 | 28.8085 | 0.980 (0.969, 0.990) | 16,539 | 6956 | 112,407.93 | 61.8818 | 1.085 (1.059, 1.112) |

| <20 | 211,197 | 52,527 | 1,880,898.38 | 27.9265 | 0.992 (0.982, 1.002) | 19,993 | 8215 | 134,768.24 | 60.9565 | 1.117 (1.091, 1.142) |

| <30 | 175,174 | 44,869 | 1,548,869.83 | 28.9689 | 1.025 (1.014, 1.037) | 19,368 | 7908 | 129,039.16 | 61.2837 | 1.150 (1.123, 1.177) |

| <40 | 98,322 | 30,092 | 832,115.32 | 36.1633 | 1.093 (1.079, 1.107) | 13,828 | 5750 | 92,573.46 | 62.1128 | 1.176 (1.144, 1.208) |

| ≥40 | 59,044 | 20,480 | 478,991.21 | 42.7565 | 1.170 (1.152, 1.188) | 25,270 | 10,760 | 161,535.85 | 66.6106 | 1.265 (1.239, 1.291) |

Appendix A.2. Association Between Smoking and LSS by 10-Year Age Bands (40–49, 50–59, 60–69, and ≥70 Years)

| Age Group | Category | N | Events | Duration (PY) | IR (per 1000 PY) | Model 4 HR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 40–49 years | Smoking | |||||

| None | 544,195 | 148,119 | 4,834,353.75 | 30.64 | 1 (Ref.) | |

| Former | 137,294 | 29,398 | 1,261,274.29 | 23.31 | 1.026 (1.012–1.040) | |

| Current | 246,597 | 51,943 | 2,254,426.63 | 23.04 | 1.029 (1.017–1.040) | |

| Smoking Duration | ||||||

| <10 | 43,090 | 9430 | 393,815.87 | 23.95 | 1.013 (0.992–1.035) | |

| <20 | 115,116 | 23,654 | 1,059,616.41 | 22.32 | 1.007 (0.992–1.022) | |

| ≥20 | 225,685 | 48,257 | 2,062,268.65 | 23.4 | 1.045 (1.033–1.058) | |

| Smoking Amount | ||||||

| <10 | 38,649 | 8536 | 352,502.35 | 24.22 | 1.011 (0.989–1.034) | |

| <20 | 147,657 | 30,050 | 1,361,334.10 | 22.07 | 0.998 (0.985–1.012) | |

| ≥20 | 197,585 | 42,755 | 1,801,864.46 | 23.73 | 1.061 (1.049–1.074) | |

| Pack-year | ||||||

| <10 | 108,482 | 22,804 | 996,145.73 | 22.89 | 0.999 (0.984–1.013) | |

| <20 | 126,740 | 25,766 | 1,168,249.29 | 22.06 | 1.012 (0.997–1.026) | |

| <30 | 105,835 | 22,383 | 968,373.34 | 23.11 | 1.046 (1.031–1.062) | |

| <40 | 29,360 | 6968 | 263,178.05 | 26.48 | 1.137 (1.109–1.166) | |

| ≥40 | 13,474 | 3420 | 119,754.50 | 28.56 | 1.198 (1.158–1.240) | |

| 50–59 years | Smoking | |||||

| None | 411,790 | 164,725 | 3,317,386.08 | 49.66 | 1 (Ref.) | |

| Former | 112,843 | 34,982 | 967,675.15 | 36.15 | 1.005 (0.993–1.018) | |

| Current | 146,289 | 45,375 | 1,233,935.28 | 36.77 | 1.032 (1.020–1.044) | |

| Smoking Duration | ||||||

| <10 | 22,069 | 6894 | 188,610.06 | 36.55 | 0.980 (0.956–1.004) | |

| <20 | 46,915 | 14,410 | 402,247.15 | 35.82 | 0.987 (0.970–1.005) | |

| ≥20 | 190,148 | 59,053 | 1,610,753.22 | 36.66 | 1.036 (1.025–1.048) | |

| Smoking Amount | ||||||

| <10 | 24,127 | 7588 | 205,330.79 | 36.96 | 0.976 (0.954–0.999) | |

| <20 | 92,067 | 27,270 | 791,947.52 | 34.43 | 0.974 (0.961–0.988) | |

| ≥20 | 142,938 | 45,499 | 1,204,332.13 | 37.78 | 1.065 (1.052–1.077) | |

| Pack-year | ||||||

| <10 | 55,429 | 17,074 | 474,632.40 | 35.97 | 0.975 (0.959–0.991) | |

| <20 | 67,291 | 19,986 | 578,502.12 | 34.55 | 0.985 (0.970–1.001) | |

| <30 | 54,810 | 16,669 | 468,546.87 | 35.58 | 1.020 (1.003–1.037) | |

| <40 | 54,274 | 17,254 | 456,174.14 | 37.82 | 1.075 (1.057–1.093) | |

| ≥40 | 27,328 | 9374 | 223,754.91 | 41.89 | 1.146 (1.121–1.171) | |

| 60–69 years | Smoking | |||||

| None | 234,680 | 120,838 | 1,658,865.29 | 72.84 | 1 (Ref.) | |

| Former | 63,700 | 26,516 | 483,507.74 | 54.84 | 1.043 (1.028–1.057) | |

| Current | 62,576 | 25,584 | 459,445.93 | 55.68 | 1.070 (1.055–1.085) | |

| Smoking Duration | ||||||

| <10 | 8086 | 3325 | 62,011.07 | 53.62 | 0.995 (0.961–1.030) | |

| <20 | 16,114 | 6629 | 123,900.78 | 53.5 | 1.008 (0.983–1.034) | |

| ≥20 | 102,076 | 42,146 | 757,041.83 | 55.67 | 1.071 (1.059–1.085) | |

| Smoking Amount | ||||||

| <10 | 15,304 | 6349 | 114,615.22 | 55.39 | 1.016 (0.990–1.042) | |

| <20 | 43,653 | 17,490 | 330,843.13 | 52.86 | 1.017 (1.000–1.034) | |

| ≥20 | 67,319 | 28,261 | 497,495.32 | 56.81 | 1.097 (1.082–1.113) | |

| Pack-year | ||||||

| <10 | 22,502 | 9291 | 171,676.93 | 54.12 | 1.006 (0.984–1.027) | |

| <20 | 27,136 | 10,957 | 206,175.28 | 53.14 | 1.018 (0.998–1.039) | |

| <30 | 23,692 | 9655 | 177,381.99 | 54.43 | 1.053 (1.031–1.076) | |

| <40 | 22,014 | 8976 | 165,051.01 | 54.38 | 1.064 (1.041–1.087) | |

| ≥40 | 30,932 | 13,221 | 222,668.46 | 59.38 | 1.146 (1.125–1.168) | |

| ≥70 years | Smoking | |||||

| None | 115,584 | 55,053 | 716,785.13 | 76.81 | 1 (Ref.) | |

| Former | 26,078 | 10,862 | 164,764.43 | 65.92 | 1.215 (1.190–1.241) | |

| Current | 21,642 | 8514 | 129,628.69 | 65.68 | 1.209 (1.181–1.237) | |

| Smoking Duration | ||||||

| <10 | 2504 | 1046 | 16,154.30 | 64.75 | 1.144 (1.076–1.216) | |

| <20 | 4459 | 1846 | 29,098.07 | 63.44 | 1.147 (1.095–1.202) | |

| ≥20 | 40,757 | 16,484 | 249,140.75 | 66.16 | 1.227 (1.206–1.250) | |

| Smoking Amount | ||||||

| <10 | 8996 | 3459 | 54,624.50 | 63.32 | 1.094 (1.057–1.133) | |

| <20 | 17,637 | 7105 | 111,127.01 | 63.94 | 1.192 (1.163–1.223) | |

| ≥20 | 21,087 | 8812 | 128,641.61 | 68.5 | 1.293 (1.263–1.323) | |

| Pack-year | ||||||

| <10 | 8410 | 3404 | 53,411.62 | 63.73 | 1.106 (1.068–1.146) | |

| <20 | 10,023 | 4033 | 62,739.92 | 64.28 | 1.172 (1.135–1.211) | |

| <30 | 10,205 | 4070 | 63,606.79 | 63.99 | 1.212 (1.174–1.252) | |

| <40 | 6502 | 2644 | 40,285.59 | 65.63 | 1.232 (1.185–1.281) | |

| ≥40 | 12,580 | 5225 | 74,349.19 | 70.28 | 1.339 (1.301–1.378) |

Appendix A.3. Detailed Hazard Ratios for LSS by Smoking Exposure Categories, Stratified by Sex

| Male | Female | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Event | Duration | IR, per 1000 PY | Model 4 | N | Event | Duration | IR, per 1000 PY | Model 4 | |

| Smoking | ||||||||||

| None | 357,217 | 104,334 | 3,007,774.09 | 34.6881 | 1 (Ref.) | 949,032 | 384,401 | 7,519,616.15 | 51.1198 | 1 (Ref.) |

| Former | 328,631 | 97,404 | 2,787,349.58 | 34.945 | 1.039 (1.030, 1.048) | 11,284 | 4354 | 89,872.02 | 48.4467 | 1.017 (0.987, 1.048) |

| Current | 449,310 | 119,361 | 3,865,165.72 | 30.8812 | 1.032 (1.024, 1.041) | 27,794 | 12,055 | 212,270.81 | 56.7907 | 1.161 (1.140, 1.183) |

| Smoking duration | ||||||||||

| None | 357,217 | 104,334 | 3,007,774.09 | 34.6881 | 1 (Ref.) | 949,032 | 384,401 | 7,519,616.15 | 51.1198 | 1 (Ref.) |

| <10 | 62,808 | 15,751 | 555,552.11 | 28.352 | 0.964 (0.948, 0.981) | 12,941 | 4944 | 105,039.19 | 47.0681 | 1.111 (1.080, 1.143) |

| <20 | 168,914 | 40,989 | 1,506,248.7 | 27.2126 | 0.973 (0.962, 0.984) | 13,690 | 5550 | 108,613.7 | 51.0985 | 1.144 (1.114, 1.175) |

| ≥20 | 546,219 | 160,025 | 4,590,714.5 | 34.8584 | 1.061 (1.052, 1.069) | 12,447 | 5915 | 88,489.95 | 66.8438 | 1.105 (1.076, 1.133) |

| Smoking amount | ||||||||||

| None | 357,217 | 104,334 | 3,007,774.09 | 34.6881 | 1 (Ref.) | 949,032 | 384,401 | 7,519,616.15 | 51.1198 | 1 (Ref.) |

| <10 | 70,864 | 19,610 | 598,874.88 | 32.7447 | 0.986 (0.971, 1.002) | 16,212 | 6322 | 128,197.99 | 49.3143 | 1.034 (1.009, 1.060) |

| <20 | 284,975 | 75,060 | 2,471,802.95 | 30.3665 | 0.987 (0.978, 0.997) | 16,039 | 6855 | 123,448.81 | 55.5291 | 1.161 (1.134, 1.189) |

| ≥20 | 422,102 | 122,095 | 3,581,837.47 | 34.0873 | 1.078 (1.069, 1.087) | 6827 | 3232 | 50,496.04 | 64.005 | 1.223 (1.181, 1.266) |

| Pack-year | ||||||||||

| None | 357,217 | 104,334 | 3,007,774.09 | 34.6881 | 1 (Ref.) | 949,032 | 384,401 | 7,519,616.15 | 51.1198 | 1 (Ref.) |

| <10 | 167,949 | 42,010 | 1,481,513.03 | 28.3561 | 0.960 (0.949, 0.971) | 26,874 | 10,563 | 214,353.66 | 49.2784 | 1.091 (1.070, 1.112) |

| <20 | 223,442 | 57,129 | 1,958,628.77 | 29.1679 | 0.987 (0.977, 0.998) | 7748 | 3613 | 57,037.84 | 63.3439 | 1.184 (1.146, 1.224) |

| <30 | 191,803 | 51,456 | 1,658,332.31 | 31.0288 | 1.027 (1.016, 1.038) | 2739 | 1321 | 19,576.68 | 67.4782 | 1.169 (1.107, 1.234) |

| <40 | 111,053 | 35,248 | 917,426.98 | 38.4205 | 1.108 (1.094, 1.121) | 1097 | 594 | 7261.81 | 81.7978 | 1.222 (1.128, 1.325) |

| ≥40 | 83,694 | 30,922 | 636,614.21 | 48.5726 | 1.192 (1.177, 1.208) | 620 | 318 | 3912.85 | 81.2708 | 1.030 (0.923, 1.150) |

Appendix B

Appendix B.1. Age-Stratified Analysis of Combined Smoking Status and Cumulative Exposure (40–64 vs. ≥65 Years)

| Age 40–64 Years | Age ≥ 65 Years | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Event | Duration | IR, per 1000 PY | Model 4 | N | Event | Duration | IR, per 1000 PY | Model 4 | |

| Smoking status and Duration | ||||||||||

| None | 1,099,107 | 384,974 | 9,190,028.6 | 41.8904 | 1 (Ref.) | 207,142 | 103,761 | 1,337,361.64 | 77.5863 | 1 (Ref.) |

| Ex and <10 | 46,560 | 11,739 | 416,092.6 | 28.2125 | 0.960 (0.942, 0.978) | 4171 | 1749 | 29,403.59 | 59.4825 | 1.078 (1.028, 1.130) |

| Ex and <20 | 102,062 | 25,643 | 912,671.29 | 28.0966 | 0.987 (0.973, 1.000) | 8055 | 3416 | 56,449.81 | 60.5139 | 1.121 (1.083, 1.160) |

| Ex and ≥20 | 141,071 | 43,083 | 1,208,427.59 | 35.6521 | 1.056 (1.044, 1.068) | 37,996 | 16,128 | 254,176.73 | 63.4519 | 1.162 (1.142, 1.182) |

| Current and <10 | 23,852 | 6707 | 207,405.74 | 32.3376 | 1.048 (1.023, 1.074) | 1166 | 500 | 7689.36 | 65.0249 | 1.122 (1.028, 1.226) |

| Current and <20 | 70,728 | 16,727 | 633,893.58 | 26.3877 | 0.988 (0.972, 1.004) | 1759 | 753 | 11,847.72 | 63.5565 | 1.083 (1.008, 1.164) |

| Current and ≥20 | 337,748 | 89,686 | 2,945,842.71 | 30.4449 | 1.036 (1.027, 1.045) | 41,851 | 17,043 | 270,757.42 | 62.9456 | 1.181 (1.162, 1.201) |

| Smoking status and Amount | ||||||||||

| None | 1,099,107 | 384,974 | 9,190,028.6 | 41.8904 | 1 (Ref.) | 207,142 | 103,761 | 1,337,361.64 | 77.5863 | 1 (Ref.) |

| Ex and <10 | 33,869 | 9208 | 298,378.64 | 30.8601 | 0.976 (0.955, 0.996) | 6796 | 2819 | 46,961.44 | 60.028 | 1.069 (1.030, 1.110) |

| Ex and <20 | 111,522 | 29,025 | 990,516.61 | 29.3029 | 0.976 (0.963, 0.988) | 16,595 | 6948 | 114,740 | 60.5543 | 1.111 (1.084, 1.139) |

| Ex and ≥20 | 144,302 | 42,232 | 1,248,296.22 | 33.8317 | 1.063 (1.051, 1.075) | 26,831 | 11,526 | 178,328.69 | 64.6335 | 1.196 (1.172, 1.220) |

| Current and <10 | 37,569 | 10,432 | 326,318.06 | 31.9688 | 1.012 (0.992, 1.032) | 8842 | 3473 | 55,414.73 | 62.6729 | 1.046 (1.011, 1.082) |

| Current and <20 | 155,360 | 38,848 | 1,375,079.36 | 28.2515 | 0.989 (0.977, 1.000) | 17,537 | 7094 | 114,915.78 | 61.7322 | 1.158 (1.130, 1.186) |

| Current and ≥20 | 239,399 | 63,840 | 2,085,744.6 | 30.6078 | 1.063 (1.052, 1.073) | 18,397 | 7729 | 119,964.01 | 64.4277 | 1.267 (1.238, 1.298) |

| Smoking status and Pack-year | ||||||||||

| None | 1,099,107 | 384,974 | 9,190,028.6 | 41.8904 | 1 (Ref.) | 207,142 | 103,761 | 1,337,361.64 | 77.5863 | 1 (Ref.) |

| Ex and <10 | 101,770 | 25,723 | 909,312.8 | 28.2884 | 0.963 (0.950, 0.976) | 10,918 | 4602 | 76,293.27 | 60.3199 | 1.093 (1.061, 1.126) |

| Ex and <20 | 88,423 | 23,332 | 782,979.37 | 29.799 | 1.000 (0.986, 1.014) | 11,374 | 4763 | 78,841.49 | 60.4124 | 1.118 (1.086, 1.151) |

| Ex and ≥20 | 99,500 | 31,410 | 844,899.3 | 37.176 | 1.091 (1.077, 1.105) | 27,930 | 11,928 | 184,895.37 | 64.5122 | 1.187 (1.164, 1.210) |

| Current and <10 | 76,514 | 19,894 | 674,145.96 | 29.5099 | 1.003 (0.988, 1.017) | 5621 | 2354 | 36,114.67 | 65.1813 | 1.070 (1.027, 1.114) |

| Current and <20 | 122,774 | 29,195 | 1,097,919.01 | 26.5912 | 0.985 (0.973, 0.998) | 8619 | 3452 | 55,926.74 | 61.7236 | 1.114 (1.077, 1.153) |

| Current and ≥20 | 233,040 | 64,031 | 2,015,077.06 | 31.776 | 1.064 (1.054, 1.075) | 30,536 | 12,490 | 198,253.1 | 63.0003 | 1.220 (1.196, 1.243) |

Appendix B.2. Association Between Smoking Burden and LSS by 10-Year Age Bands

- Age 40–49: Significant risk was observed among current smokers with ≥20 years (HR 1.037), ≥20 cigarettes/day (HR 1.057), or ≥20 pack-years (HR 1.092). Among former smokers, only those with ≥20 pack-years showed increased risk (HR 1.058).

- Age 50–59: Risk was significantly elevated across most high-exposure categories. Former smokers with ≥20 pack-years had HR 1.102, while current smokers had HR 1.066.

- Age 60–69: Consistent risk elevation was seen in nearly all subgroups. The HR for former smokers with ≥20 pack-years (HR 1.139) slightly exceeded that of current smokers (HR 1.092).

- Age ≥ 70: This group exhibited the highest and most consistent risk. Current smokers with ≥20 years of smoking (HR 1.220), ≥20 cigarettes/day (HR 1.289), and ≥20 pack-years (HR 1.231) showed substantial increases, highlighting the amplified harm of continued smoking in older adults.

| Age Group | Category | N | Events | Duration (PY) | IR (per 1000 PY) | Model 4 HR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 40–49 years | Smoking status and Duration | |||||

| None | 544,195 | 148,119 | 4,834,353.75 | 30.6388 | 1 (Ref.) | |

| Ex and <10 | 27,747 | 5762 | 255,757.17 | 22.5292 | 0.981 (0.956, 1.008) | |

| Ex and <20 | 61,787 | 12,800 | 570,044.06 | 22.4544 | 1.014 (0.995, 1.033) | |

| Ex and ≥20 | 47,760 | 10,836 | 435,473.06 | 24.8833 | 1.071 (1.050, 1.093) | |

| Current and <10 | 15,343 | 3668 | 138,058.69 | 26.5684 | 1.067 (1.032, 1.102) | |

| Current and <20 | 53,329 | 10,854 | 489,572.35 | 22.1704 | 0.998 (0.978, 1.018) | |

| Current and ≥20 | 177,925 | 37,421 | 1,626,795.59 | 23.0029 | 1.037 (1.024, 1.050) | |

| Smoking status and amount | ||||||

| None | 544,195 | 148,119 | 4,834,353.75 | 30.6388 | 1 (Ref.) | |

| Ex and <10 | 17,126 | 3718 | 156,889.87 | 23.6982 | 1.005 (0.972, 1.038) | |

| Ex and <20 | 56,432 | 11,515 | 522,206.31 | 22.0507 | 0.992 (0.973, 1.012) | |

| Ex and ≥20 | 63,736 | 14,165 | 582,178.11 | 24.331 | 1.069 (1.050, 1.088) | |

| Current and <10 | 21,523 | 4818 | 195,612.48 | 24.6303 | 1.016 (0.987, 1.046) | |

| Current and <20 | 91,225 | 18,535 | 839,127.79 | 22.0884 | 1.002 (0.986, 1.018) | |

| Current and ≥20 | 133,849 | 28,590 | 1,219,686.35 | 23.4405 | 1.057 (1.043, 1.072) | |

| Smoking status and Pack-year | ||||||

| None | 544,195 | 148,119 | 4,834,353.75 | 30.6388 | 1 (Ref.) | |

| Ex and <10 | 58,208 | 11,917 | 537,933.86 | 22.1533 | 0.984 (0.966, 1.004) | |

| Ex and <20 | 46,003 | 9721 | 423,526.72 | 22.9525 | 1.032 (1.010, 1.054) | |

| Ex and ≥20 | 33,083 | 7760 | 299,813.71 | 25.8827 | 1.107 (1.081, 1.133) | |

| Current and <10 | 50,274 | 10,887 | 458,211.87 | 23.7598 | 1.013 (0.993, 1.034) | |

| Current and <20 | 80,737 | 16,045 | 744,722.58 | 21.5449 | 0.998 (0.981, 1.015) | |

| Current and ≥20 | 115,586 | 25,011 | 1,051,492.19 | 23.7862 | 1.068 (1.052, 1.083) | |

| 50–59 years | Smoking status and Duration | |||||

| None | 411,790 | 164,725 | 3,317,386.08 | 49.6551 | 1 (Ref.) | |

| Ex and <10 | 14,921 | 4432 | 129,554.59 | 34.2095 | 0.943 (0.915, 0.972) | |

| Ex and <20 | 31,969 | 9569 | 276,704.22 | 34.5821 | 0.974 (0.953, 0.994) | |

| Ex and ≥20 | 65,953 | 20,981 | 561,416.34 | 37.3716 | 1.038 (1.022, 1.054) | |

| Current and <10 | 7148 | 2462 | 59,055.47 | 41.6896 | 1.052 (1.011, 1.095) | |

| Current and <20 | 14,946 | 4841 | 125,542.93 | 38.5605 | 1.014 (0.985, 1.044) | |

| Current and ≥20 | 124,195 | 38,072 | 1,049,336.88 | 36.282 | 1.035 (1.022, 1.047) | |

| Smoking status and amount | ||||||

| None | 411,790 | 164,725 | 3,317,386.08 | 49.6551 | 1 (Ref.) | |

| Ex and <10 | 12,154 | 3662 | 105,270 | 34.7867 | 0.945 (0.915, 0.977) | |

| Ex and <20 | 41,873 | 12,302 | 363,566.82 | 33.837 | 0.959 (0.941, 0.978) | |

| Ex and ≥20 | 58,816 | 19,018 | 498,838.33 | 38.1246 | 1.057 (1.040, 1.074) | |

| Current and <10 | 11,973 | 3926 | 100,060.79 | 39.2361 | 1.006 (0.975, 1.039) | |

| Current and <20 | 50,194 | 14,968 | 428,380.7 | 34.9409 | 0.986 (0.969, 1.004) | |

| Current and ≥20 | 84,122 | 26,481 | 705,493.79 | 37.5354 | 1.070 (1.055, 1.085) | |

| Smoking status and Pack-year | ||||||

| None | 411,790 | 164,725 | 3,317,386.08 | 49.6551 | 1 (Ref.) | |

| Ex and <10 | 33,881 | 10,031 | 294,240.46 | 34.0912 | 0.952 (0.932, 0.971) | |

| Ex and <20 | 32,561 | 9691 | 281,697.45 | 34.4022 | 0.976 (0.956, 0.997) | |

| Ex and ≥20 | 46,401 | 15,260 | 391,737.24 | 38.9547 | 1.075 (1.057, 1.094) | |

| Current and <10 | 21,548 | 7043 | 180,391.94 | 39.0428 | 1.009 (0.985, 1.034) | |

| Current and <20 | 34,730 | 10,295 | 296,804.67 | 34.6861 | 0.992 (0.972, 1.013) | |

| Current and ≥20 | 90,011 | 28,037 | 756,738.68 | 37.0498 | 1.060 (1.046, 1.075) | |

| 60–69 years | Smoking status and Duration | |||||

| None | 234,680 | 120,838 | 1,658,865.29 | 72.8438 | 1 (Ref.) | |

| Ex and <10 | 6032 | 2445 | 46,865.45 | 52.1706 | 0.983 (0.944, 1.023) | |

| Ex and <20 | 12,568 | 5109 | 97,522.43 | 52.3879 | 1.006 (0.977, 1.035) | |

| Ex and ≥20 | 45,100 | 18,962 | 339,119.86 | 55.9153 | 1.064 (1.047, 1.081) | |

| Current and <10 | 2054 | 880 | 15,145.61 | 58.1026 | 1.029 (0.963, 1.099) | |

| Current and <20 | 3546 | 1520 | 26,378.35 | 57.623 | 1.013 (0.963, 1.066) | |

| Current and ≥20 | 56,976 | 23,184 | 417,921.97 | 55.4745 | 1.077 (1.061, 1.093) | |

| Smoking status and amount | ||||||

| None | 234,680 | 120,838 | 1,658,865.29 | 72.8438 | 1 (Ref.) | |

| Ex and <10 | 7810 | 3213 | 60,146.81 | 53.4193 | 0.997 (0.963, 1.033) | |

| Ex and <20 | 20,993 | 8507 | 162,021.57 | 52.5054 | 1.010 (0.987, 1.033) | |

| Ex and ≥20 | 34,897 | 14,796 | 261,339.37 | 56.616 | 1.079 (1.060, 1.098) | |

| Current and <10 | 7494 | 3136 | 54,468.42 | 57.5746 | 1.035 (0.999, 1.073) | |

| Current and <20 | 22,660 | 8983 | 168,821.56 | 53.21 | 1.024 (1.001, 1.046) | |

| Current and ≥20 | 32,422 | 13,465 | 236,155.95 | 57.0174 | 1.118 (1.098, 1.139) | |

| Smoking status and Pack-year | ||||||

| None | 234,680 | 120,838 | 1,658,865.29 | 72.8438 | 1 (Ref.) | |

| Ex and <10 | 15,106 | 6126 | 117,395.9 | 52.1824 | 0.992 (0.966, 1.018) | |

| Ex and <20 | 15,537 | 6298 | 119,705.7 | 52.6124 | 1.013 (0.987, 1.040) | |

| Ex and ≥20 | 33,057 | 14,092 | 246,406.15 | 57.1901 | 1.088 (1.068, 1.108) | |

| Current and <10 | 7396 | 3165 | 54,281.03 | 58.3077 | 1.032 (0.996, 1.069) | |

| Current and <20 | 11,599 | 4659 | 86,469.59 | 53.8802 | 1.024 (0.994, 1.055) | |

| Current and ≥20 | 43,581 | 17,760 | 318,695.31 | 55.7272 | 1.095 (1.077, 1.114) | |

| ≥70 years | Smoking status and Duration | |||||

| None | 115,584 | 55,053 | 716,785.13 | 76.8054 | 1 (Ref.) | |

| Ex and <10 | 2031 | 849 | 13,318.97 | 63.7437 | 1.143 (1.068, 1.224) | |

| Ex and <20 | 3793 | 1581 | 24,850.39 | 63.6207 | 1.173 (1.115, 1.233) | |

| Ex and ≥20 | 20,254 | 8432 | 126,595.06 | 66.6061 | 1.234 (1.205, 1.263) | |

| Current and <10 | 473 | 197 | 2835.33 | 69.4805 | 1.142 (0.993, 1.314) | |

| Current and <20 | 666 | 265 | 4247.67 | 62.3871 | 1.010 (0.896, 1.140) | |

| Current and ≥20 | 20,503 | 8052 | 122,545.68 | 65.7061 | 1.220 (1.191, 1.249) | |

| Smoking status and amount | ||||||

| None | 115,584 | 55,053 | 716,785.13 | 76.8054 | 1 (Ref.) | |

| Ex and <10 | 3575 | 1434 | 23,033.41 | 62.2574 | 1.107 (1.050, 1.167) | |

| Ex and <20 | 8819 | 3649 | 57,461.92 | 63.5029 | 1.177 (1.138, 1.218) | |

| Ex and ≥20 | 13,684 | 5779 | 84,269.1 | 68.5779 | 1.279 (1.244, 1.315) | |

| Current and <10 | 5421 | 2025 | 31,591.1 | 64.1003 | 1.086 (1.038, 1.135) | |

| Current and <20 | 8818 | 3456 | 53,665.08 | 64.3994 | 1.208 (1.167, 1.250) | |

| Current and ≥20 | 7403 | 3033 | 44,372.51 | 68.3531 | 1.319 (1.271, 1.368) | |

| Smoking status and Pack-year | ||||||

| None | 115,584 | 55,053 | 716,785.13 | 76.8054 | 1 (Ref.) | |

| Ex and <10 | 5493 | 2251 | 36,035.84 | 62.4656 | 1.129 (1.082, 1.177) | |

| Ex and <20 | 5696 | 2385 | 36,891 | 64.6499 | 1.197 (1.149, 1.248) | |

| Ex and ≥20 | 14,889 | 6226 | 91,837.59 | 67.7936 | 1.265 (1.232, 1.299) | |

| Current and <10 | 2917 | 1153 | 17,375.78 | 66.3567 | 1.065 (1.004, 1.129) | |

| Current and <20 | 4327 | 1648 | 25,848.92 | 63.7551 | 1.137 (1.082, 1.194) | |

| Current and ≥20 | 14,398 | 5713 | 86,403.98 | 66.1196 | 1.272 (1.237, 1.308) |

Appendix B.3. Sex-Stratified Association Between Combined Smoking Burden and LSS Risk

| Male | Female | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Event | Duration | IR, per 1000 PY | Model 4 | N | Event | Duration | IR, per 1000 PY | Model 4 | |

| Smoking status and Duration | ||||||||||

| None | 357,217 | 104,334 | 3,007,774.09 | 34.6881 | 1 (Ref.) | 949,032 | 384,401 | 7,519,616.15 | 51.1198 | 1 (Ref.) |

| Ex and <10 | 44,935 | 11,429 | 397,632.64 | 28.7426 | 0.960 (0.942, 0.979) | 5796 | 2059 | 47,863.55 | 43.0181 | 1.014 (0.971, 1.059) |

| Ex and <20 | 106,652 | 27,717 | 941,295.46 | 29.4456 | 0.993 (0.980, 1.006) | 3465 | 1342 | 27,825.64 | 48.2289 | 1.038 (0.984, 1.095) |

| Ex and ≥20 | 177,044 | 58,258 | 1,448,421.49 | 40.2217 | 1.080 (1.069, 1.091) | 2023 | 953 | 14,182.83 | 67.1939 | 0.995 (0.934, 1.061) |

| Current and <10 | 17,873 | 4322 | 157,919.47 | 27.3684 | 0.973 (0.944, 1.003) | 7145 | 2885 | 57,175.63 | 50.4586 | 1.191 (1.148, 1.235) |

| Current and <20 | 62,262 | 13,272 | 564,953.24 | 23.4922 | 0.931 (0.914, 0.948) | 10,225 | 4208 | 80,788.06 | 52.0869 | 1.182 (1.147, 1.219) |

| Current and ≥20 | 369,175 | 101,767 | 3,142,293.01 | 32.3862 | 1.049 (1.040, 1.059) | 10,424 | 4962 | 74,307.12 | 66.7769 | 1.129 (1.097, 1.161) |

| Smoking status and amount | ||||||||||

| None | 357,217 | 104,334 | 3,007,774.09 | 34.6881 | 1 (Ref.) | 949,032 | 384,401 | 7,519,616.15 | 51.1198 | 1 (Ref.) |

| Ex and <10 | 35,010 | 9971 | 299,350.64 | 33.3088 | 0.989 (0.969, 1.010) | 5655 | 2056 | 45,989.44 | 44.7059 | 0.979 (0.937, 1.022) |

| Ex and <20 | 124,059 | 34,380 | 1,072,986.15 | 32.0414 | 0.992 (0.979, 1.004) | 4058 | 1593 | 32,270.46 | 49.364 | 1.039 (0.989, 1.092) |

| Ex and ≥20 | 169,562 | 53,053 | 1,415,012.78 | 37.4929 | 1.084 (1.072, 1.095) | 1571 | 705 | 11,612.12 | 60.7124 | 1.091 (1.013, 1.174) |

| Current and <10 | 35,854 | 9639 | 299,524.24 | 32.181 | 0.984 (0.963, 1.005) | 10,557 | 4266 | 82,208.55 | 51.8924 | 1.063 (1.032, 1.096) |

| Current and <20 | 160,916 | 40,680 | 1,398,816.79 | 29.0817 | 0.983 (0.972, 0.995) | 11,981 | 5262 | 91,178.35 | 57.7111 | 1.204 (1.172, 1.237) |

| Current and ≥20 | 252,540 | 69,042 | 2,166,824.69 | 31.8632 | 1.073 (1.063, 1.084) | 5256 | 2527 | 38,883.92 | 64.9883 | 1.266 (1.217, 1.316) |

| Smoking status and Pack-year | ||||||||||

| None | 357,217 | 104,334 | 3,007,774.09 | 34.6881 | 1 (Ref.) | 949,032 | 384,401 | 7,519,616.15 | 51.1198 | 1 (Ref.) |

| Ex and <10 | 103,602 | 26,995 | 911,509.23 | 29.6157 | 0.970 (0.957, 0.983) | 9086 | 3330 | 74,096.83 | 44.9412 | 1.004 (0.970, 1.039) |

| Ex and <20 | 98,397 | 27,458 | 851,443.59 | 32.2488 | 1.009 (0.996, 1.023) | 1400 | 637 | 10,377.28 | 61.3841 | 1.097 (1.015, 1.186) |

| Ex and ≥20 | 126,632 | 42,951 | 1,024,396.76 | 41.9281 | 1.109 (1.097, 1.122) | 798 | 387 | 5397.92 | 71.6943 | 1.006 (0.911, 1.112) |

| Current and <10 | 64,347 | 15,015 | 570,003.8 | 26.3419 | 0.947 (0.930, 0.963) | 17,788 | 7233 | 140,256.82 | 51.5697 | 1.137 (1.111, 1.164) |

| Current and <20 | 125,045 | 29,671 | 1,107,185.19 | 26.7986 | 0.970 (0.957, 0.983) | 6348 | 2976 | 46,660.57 | 63.7798 | 1.204 (1.161, 1.248) |

| Current and ≥20 | 259,918 | 74,675 | 2,187,976.73 | 34.1297 | 1.079 (1.069, 1.090) | 3658 | 1846 | 25,353.42 | 72.8107 | 1.195 (1.142, 1.251) |

Appendix C

Appendix C.1. Subgroup and Interaction Analyses for Smoking-Related Risk of LSS

| Smoking | N | Event | Duration | IR, per 1000 PY | HR (95% C.I) | p for Interaction | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age groups | 40–64 | None | 1,099,107 | 384,974 | 9,190,028.6 | 41.8904 | 1 (Ref.) | <0.0001 |

| Former | 289,693 | 80,465 | 2,537,191.47 | 31.7142 | 1.016 (1.007, 1.025) | |||

| Current | 432,328 | 113,120 | 3,787,142.02 | 29.8695 | 1.027 (1.019, 1.036) | |||

| ≥65 | None | 207,142 | 103,761 | 1,337,361.64 | 77.5863 | 1 (Ref.) | ||

| Former | 50,222 | 21,293 | 340,030.13 | 62.6209 | 1.146 (1.129, 1.164) | |||

| Current | 44,776 | 18,296 | 290,294.51 | 63.0256 | 1.174 (1.155, 1.193) | |||

| Sex | Male | None | 357,217 | 104,334 | 3,007,774.09 | 34.6881 | 1 (Ref.) | <0.0001 |

| Former | 328,631 | 97,404 | 2,787,349.58 | 34.945 | 1.039 (1.030, 1.048) | |||

| Current | 449,310 | 119,361 | 3,865,165.72 | 30.8812 | 1.032 (1.024, 1.041) | |||

| Female | None | 949,032 | 384,401 | 7,519,616.15 | 51.1198 | 1 (Ref.) | ||

| Former | 11,284 | 4354 | 89,872.02 | 48.4467 | 1.017 (0.987, 1.048) | |||

| Current | 27,794 | 12,055 | 212,270.81 | 56.7907 | 1.161 (1.140, 1.183) | |||

| Income | Q2–4 | None | 1,012,450 | 372,930 | 8,188,085.61 | 45.5454 | 1 (Ref.) | 0.0005 |

| Former | 289,948 | 84,875 | 2,471,224.75 | 34.3453 | 1.051 (1.042, 1.060) | |||

| Current | 389,716 | 104,906 | 3,356,176.65 | 31.2576 | 1.058 (1.049, 1.067) | |||

| Q1 | None | 293,799 | 115,805 | 2,339,304.63 | 49.504 | 1 (Ref.) | ||

| Former | 49,967 | 16,883 | 405,996.85 | 41.5841 | 1.032 (1.015, 1.050) | |||

| Current | 87,388 | 26,510 | 721,259.88 | 36.7551 | 1.029 (1.015, 1.044) | |||

| Obesity BMI ≥ 25 | No | None | 888,363 | 311,645 | 7,285,125.45 | 42.7783 | 1 (Ref.) | <0.0001 |

| Former | 201,186 | 57,927 | 1,706,108.62 | 33.9527 | 1.064 (1.053, 1.075) | |||

| Current | 315,768 | 85,234 | 2,690,884.35 | 31.6751 | 1.084 (1.074, 1.094) | |||

| Yes | None | 417,886 | 177,090 | 3,242,264.79 | 54.6192 | 1 (Ref.) | ||

| Former | 138,729 | 43,831 | 1,171,112.99 | 37.4268 | 1.023 (1.011, 1.035) | |||

| Current | 161,336 | 46,182 | 1,386,552.18 | 33.3071 | 0.997 (0.986, 1.009) | |||

| Abdominal obesity WC ≥ 90/85 | No | None | 1,050,019 | 373,418 | 8,611,942.99 | 43.3605 | 1 (Ref.) | <0.0001 |

| Former | 254,634 | 72,921 | 2,176,702.42 | 33.5007 | 1.050 (1.040, 1.059) | |||

| Current | 375,478 | 100,325 | 3,224,739.94 | 31.111 | 1.061 (1.052, 1.071) | |||

| Yes | None | 256,230 | 115,317 | 1,915,447.25 | 60.2037 | 1 (Ref.) | ||

| Former | 85,281 | 28,837 | 700,519.18 | 41.1652 | 1.039 (1.025, 1.054) | |||

| Current | 101,626 | 31,091 | 852,696.59 | 36.462 | 1.020 (1.006, 1.033) | |||

| Heavy Drinking | No | None | 1,274,037 | 477,654 | 10,263,653.04 | 46.5384 | 1 (Ref.) | <0.0001 |

| Former | 294,203 | 87,686 | 2,489,838.14 | 35.2176 | 1.052 (1.043, 1.062) | |||

| Current | 388,734 | 106,440 | 3,328,505.56 | 31.9783 | 1.057 (1.049, 1.066) | |||

| Yes | None | 32,212 | 11,081 | 263,737.2 | 42.0153 | 1 (Ref.) | ||

| Former | 45,712 | 14,072 | 387,383.46 | 36.3258 | 0.998 (0.974, 1.023) | |||

| Current | 88,370 | 24,976 | 748,930.97 | 33.3489 | 1.004 (0.982, 1.027) | |||

| Regular exercise | No | None | 1,056,687 | 394,391 | 8,510,009.22 | 46.3444 | 1 (Ref.) | 0.0006 |

| Former | 247,026 | 73,379 | 2,091,526.47 | 35.0839 | 1.055 (1.046, 1.065) | |||

| Current | 390,873 | 106,624 | 3,346,129.42 | 31.8649 | 1.052 (1.043, 1.060) | |||

| Yes | None | 249,562 | 94,344 | 2,017,381.02 | 46.7656 | 1 (Ref.) | ||

| Former | 92,889 | 28,379 | 785,695.13 | 36.1196 | 1.025 (1.011, 1.040) | |||

| Current | 86,231 | 24,792 | 731,307.12 | 33.9009 | 1.055 (1.039, 1.070) | |||

| Diabetes mellitus | No | None | 1,182,850 | 436,748 | 9,617,386.13 | 45.4123 | 1 (Ref.) | 0.6053 |

| Former | 293,360 | 86,456 | 2,504,674.67 | 34.5179 | 1.047 (1.038, 1.056) | |||

| Current | 414,622 | 112,825 | 3,571,551.9 | 31.5899 | 1.051 (1.042, 1.059) | |||

| Yes | None | 123,399 | 51,987 | 910,004.11 | 57.1283 | 1 (Ref.) | ||

| Former | 46,555 | 15,302 | 372,546.93 | 41.074 | 1.050 (1.031, 1.070) | |||

| Current | 62,482 | 18,591 | 505,884.64 | 36.7495 | 1.060 (1.042, 1.079) | |||

| Hypertension | No | None | 915,672 | 320,598 | 7,602,004.07 | 42.1728 | 1 (Ref.) | <0.0001 |

| Former | 214,932 | 60,003 | 1,865,175.94 | 32.1702 | 1.039 (1.029, 1.050) | |||

| Current | 336,565 | 88,176 | 2,931,440.05 | 30.0794 | 1.043 (1.033, 1.052) | |||

| Yes | None | 390,577 | 168,137 | 2,925,386.18 | 57.4751 | 1 (Ref.) | ||

| Former | 124,983 | 41,755 | 1,012,045.67 | 41.258 | 1.059 (1.047, 1.072) | |||

| Current | 140,539 | 43,240 | 1,145,996.49 | 37.7314 | 1.071 (1.058, 1.083) | |||

| Dyslipidemia | No | None | 1,029,585 | 368,292 | 8,421,523.44 | 43.7322 | 1 (Ref.) | 0.9503 |

| Former | 263,858 | 77,121 | 2,247,188.26 | 34.3189 | 1.048 (1.038, 1.058) | |||

| Current | 383,004 | 103,183 | 3,287,469.18 | 31.3868 | 1.052 (1.043, 1.061) | |||

| Yes | None | 276,664 | 120,443 | 2,105,866.8 | 57.194 | 1 (Ref.) | ||

| Former | 76,057 | 24,637 | 630,033.34 | 39.1043 | 1.045 (1.030, 1.061) | |||

| Current | 94,100 | 28,233 | 789,967.36 | 35.7395 | 1.052 (1.037, 1.066) |

Appendix D

Standardized Mean Differences (SMDs) for Baseline Characteristics

| Non vs. Former | Non vs. Current | Former vs. Current | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 0.00 | 0.25 | 0.27 |

| Height, cm | −1.13 | −1.18 | −0.06 |

| Weight, kg | −0.92 | −0.72 | 0.18 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | −0.21 | −0.01 | 0.2 |

| Waist Circumference, cm | −0.66 | −0.49 | 0.18 |

| Systolic BP, mmHg | −0.21 | −0.11 | 0.10 |

| Diastolic BP, mmHg | −0.26 | −0.2 | 0.06 |

| Fasting glucose, mg/dL | −0.19 | −0.17 | 0.01 |

| Total Cholesterol, mg/dL | 0.02 | 0.01 | −0.02 |

| HDL-C, mg/dL | 0.13 | 0.15 | 0.02 |

| LDL-C, mg/dL | 0.08 | 0.14 | 0.06 |

| Triglyceride, mg/dL | −0.21 | −0.31 | −0.09 |

References

- Rhon, D. Lumbar Spinal Stenosis (Correspondence). N. Engl. J. Med. 2008, 358, 2647–2648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walter, K.L.; O’Toole, J.E. Lumbar Spinal Stenosis (JAMA Patient Page). JAMA 2022, 328, 310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myllykangas, H.; Ristolainen, L.; Hurri, H.; Lohikoski, J.; Kautiainen, H.; Puisto, V.; Österman, H.; Manninen, M. Obese people benefit from lumbar LSS surgery as much as people of normal weight. J. Orthop. Surg. Res. 2021, 16, 550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giri, B.; Singh, D.B.; Chattu, V.K. Aging population in South Korea: Burden or opportunity? IJS Glob. Health 2024, 7, e00517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryu, J.H.; Han, K.; Kim, J.Y. Association Between Higher Body Mass Index and the Risk of Lumbar LSS in Korean Populations: A Nationwide Cohort Study. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 7397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amin, S.; Niu, J.; Guermazi, A.; Grigoryan, M.; Hunter, D.J.; Clancy, M.; LaValley, M.P.; Genant, H.K.; Felson, D.T. Cigarette smoking and the risk for cartilage loss and knee pain in men with knee osteoarthritis. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2007, 66, 18–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagley, C.; MacAllister, M.; Dosselman, L.; Moreno, J.; Aoun, S.G.; El Ahmadieh, T.Y. Current concepts and recent advances in understanding and managing lumbar spine stenosis. F1000Research 2019, 8, 137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elmasry, S.; Asfour, S.; de Rivero Vaccari, J.P.; Travascio, F. Effects of Tobacco Smoking on the Degeneration of the Intervertebral Disc: A Finite Element Study. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0136137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Geer, C.M. Intervertebral Disk Nutrients and Transport Mechanisms in Relation to Disk Degeneration: A Narrative Literature Review. J. Chiropr. Med. 2018, 17, 97–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiri, R.; Karppinen, J.; Leino-Arjas, P.; Solovieva, S.; Viikari-Juntura, E. The association between smoking and low back pain: A meta-analysis. Am. J. Med. 2010, 123, 87.e7–87.e35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, G.H. Causal relationship between smoking and LSS: Two-sample Mendelian randomization. Medicine 2024, 103, e39783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajesh, N.; Moudgil-Joshi, J.; Kaliaperumal, C. Smoking and degenerative spinal disease: A systematic review. Brain Spine 2022, 2, 100916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khurana, V.G. Adverse impact of smoking on the spine and spinal surgery. Surg. Neurol. Int. 2021, 12, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, S.E.; Seo, M.H.; Cho, J.-H.; Kwon, H.; Kim, Y.-H.; Han, K.-D.; Jung, J.-H.; Park, Y.-G.; Rhee, E.-J.; Lee, W.-Y. Dose-Dependent Effect of Smoking on Risk of Diabetes Remains after Smoking Cessation: A Nationwide Population-Based Cohort Study in Korea. Diabetes Metab. J. 2021, 45, 539–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.K.; Kim, H.C.; Shim, J.-S.; Kim, D.J. Effects of cigarette smoking on blood lipids in Korean men: Cardiovascular and Metabolic Diseases Etiology Research Center cohort. Korean J. Intern. Med. 2020, 35, 369–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uei, H.; Matsuzaki, H.; Oda, H.; Nakajima, S.; Tokuhashi, Y.; Esumi, M. Gene expression changes in an early stage of intervertebral disc degeneration induced by passive cigarette smoking. Spine 2006, 31, 510–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradford, S.T.; Stamatovic, S.M.; Dondeti, R.S.; Keep, R.F.; Andjelkovic, A.V. Nicotine aggravates the brain postischemic inflammatory response. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2011, 300, H1518–H1529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fagerström, K. The epidemiology of smoking: Health consequences and benefits of cessation. Drugs 2002, 62 (Suppl. S2), 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khullar, D.; Maa, J. The impact of smoking on surgical outcomes. J. Am. Coll. Surg. 2012, 215, 418–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oh, K.; Kim, Y.; Kweon, S.; Kim, S.; Yun, S.; Park, S.; Lee, Y.K.; Kim, Y.; Park, O.; Jeong, E.K. Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 20th anniversary: Accomplishments and future directions. Epidemiol. Health 2021, 43, e2021025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ward, K.D.; Klesges, R.C. A meta-analysis of the effects of cigarette smoking on bone mineral density. Calcif. Tissue Int. 2001, 68, 259–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, S.Y.; Yang, M.-Y.; Salo, S.; Sund, R.; Sirola, J.; Kröger, H.; Yoo, H.; Kang, M.-Y. Occupational risk factors for lumbar spinal stenosis: A systematic review. Occup. Med. 2025, 75, 91–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lou, C.; Chen, H.; Mei, L.; Yu, W.; Zhu, K.; Liu, F.; Chen, Z.; Xiang, G.; Chen, M.; Weng, Q.; et al. Association between menopause and lumbar disc degeneration: An MRI study of 1566 women and 1382 men. Menopause 2017, 24, 1279–1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahn, J.; Park, H.-S.; Cho, S.J.; Baek, S.; Rhee, Y.; Hong, N. Association of secondhand smoke with fracture risk in community-dwelling nonsmoking adults in Korea. JBMR Plus 2024, 8, ziae010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Never Smoker | Former Smoker | Current Smoker | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | 1,306,249 | 339,915 | 477,104 | |

| Age groups | <0.0001 | |||

| 40–64 | 1,099,107 (84.14) | 289,693 (85.23) | 432,328 (90.62) | |

| ≥65 | 207,142 (15.86) | 50,222 (14.77) | 44,776 (9.38) | |

| Sex | <0.0001 | |||

| Male | 357,217 (27.35) | 328,631 (96.68) | 449,310 (94.17) | |

| Female | 949,032 (72.65) | 11,284 (3.32) | 27,794 (5.83) | |

| Income, Lowest Q1 | 293,799 (22.49) | 49,967 (14.7) | 87,388 (18.32) | <0.0001 |

| BMI Level | <0.0001 | |||

| <18.5 | 31,271 (2.39) | 4627 (1.36) | 14,090 (2.95) | |

| <23 | 517,639 (39.63) | 97,415 (28.66) | 176,102 (36.91) | |

| <25 | 339,453 (25.99) | 99,144 (29.17) | 125,576 (26.32) | |

| <30 | 375,050 (28.71) | 128,663 (37.85) | 148,090 (31.04) | |

| ≥30 | 42,836 (3.28) | 10,066 (2.96) | 13,246 (2.78) | |

| Alcohol consumption | <0.0001 | |||

| None | 954,210 (73.05) | 106,525 (31.34) | 122,164 (25.61) | |

| Moderate | 319,827 (24.48) | 187,678 (55.21) | 266,570 (55.87) | |

| Heavy | 32,212 (2.47) | 45,712 (13.45) | 88,370 (18.52) | |

| Regular exercise | 249,562 (19.11) | 92,889 (27.33) | 86,231 (18.07) | <0.0001 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 123,399 (9.45) | 46,555 (13.7) | 62,482 (13.1) | <0.0001 |

| Hypertension | 390,577 (29.9) | 124,983 (36.77) | 140,539 (29.46) | <0.0001 |

| Dyslipidemia | 276,664 (21.18) | 76,057 (22.38) | 94,100 (19.72) | <0.0001 |

| Age, years | 53.38 ± 10.16 | 53.42 ± 9.72 | 50.89 ± 8.95 | <0.0001 |

| Height, cm | 158.88 ± 7.89 | 168.24 ± 6.23 | 168 ± 6.63 | <0.0001 |

| Weight, kg | 60.16 ± 9.85 | 69.19 ± 9.62 | 67.36 ± 10.4 | <0.0001 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 23.77 ± 3.06 | 24.4 ± 2.8 | 23.81 ± 3.03 | <0.0001 |

| Waist Circumference, cm | 79.14 ± 8.64 | 84.69 ± 7.43 | 83.29 ± 7.86 | <0.0001 |

| Systolic BP, mmHg | 122.9 ± 15.74 | 126.19 ± 14.58 | 124.67 ± 15.05 | <0.0001 |

| Diastolic BP, mmHg | 76.25 ± 10.3 | 78.92 ± 9.93 | 78.29 ± 10.23 | <0.0001 |

| Fasting glucose, mg/dL | 98.18 ± 23.76 | 102.87 ± 27.04 | 102.52 ± 30.45 | <0.0001 |

| Total Cholesterol, mg/dL | 198.81 ± 36.93 | 197.91 ± 36.81 | 198.61 ± 37.38 | <0.0001 |

| HDL-C, mg/dL | 57.28 ± 30.43 | 53.42 ± 25.44 | 52.98 ± 26.26 | <0.0001 |

| LDL-C, mg/dL | 118.27 ± 38.32 | 115.1 ± 37.79 | 112.97 ± 39.36 | <0.0001 |

| Triglyceride, mg/dL | 106.45 (106.35–106.55) | 129.56 (129.32–129.81) | 142.5 (142.27–142.73) | <0.0001 |

| N | Event | Duration | IR, per 1000 PY | HR (95% C.I) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | |||||

| Smoking | ||||||||

| None | 1,306,249 | 488,735 | 10,527,390.24 | 46.4251 | 1 (Ref.) | 1 (Ref.) | 1 (Ref.) | 1 (Ref.) |

| Former | 339,915 | 101,758 | 2,877,221.61 | 35.3668 | 0.761 (0.756, 0.766) | 1.064 (1.056, 1.073) | 1.049 (1.040, 1.058) | 1.047 (1.039, 1.056) |

| Current | 477,104 | 131,416 | 4,077,436.53 | 32.2301 | 0.694 (0.689, 0.698) | 1.054 (1.046, 1.062) | 1.054 (1.045, 1.062) | 1.052 (1.044, 1.060) |

| p-value | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | ||||

| Smoking duration | ||||||||

| None | 1,306,249 | 488,735 | 10,527,390.24 | 46.4251 | 1 (Ref.) | 1 (Ref.) | 1 (Ref.) | 1 (Ref.) |

| <10 | 75,749 | 20,695 | 660,591.29 | 31.328 | 0.674 (0.665, 0.684) | 1.008 (0.994, 1.023) | 1.005 (0.991, 1.020) | 1.005 (0.990, 1.019) |

| <20 | 182,604 | 46,539 | 1,614,862.4 | 28.8192 | 0.620 (0.615, 0.626) | 1.013 (1.002, 1.024) | 1.003 (0.992, 1.014) | 1.001 (0.991, 1.012) |

| ≥20 | 558,666 | 165,940 | 4,679,204.45 | 35.4633 | 0.763 (0.759, 0.768) | 1.082 (1.074, 1.090) | 1.076 (1.068, 1.084) | 1.074 (1.066, 1.082) |

| p-value | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | ||||

| Smoking amount | ||||||||

| None | 1,306,249 | 488,735 | 10,527,390.24 | 46.4251 | 1 (Ref.) | 1 (Ref.) | 1 (Ref.) | 1 (Ref.) |

| <10 | 87,076 | 25,932 | 727,072.87 | 35.6663 | 0.768 (0.758, 0.777) | 0.999 (0.986, 1.012) | 1.007 (0.994, 1.020) | 1.007 (0.994, 1.020) |

| <20 | 301,014 | 81,915 | 2,595,251.76 | 31.5634 | 0.679 (0.674, 0.684) | 1.009 (1.000, 1.018) | 1.013 (1.004, 1.022) | 1.011 (1.003, 1.020) |

| ≥20 | 428,929 | 125,327 | 3,632,333.51 | 34.5032 | 0.743 (0.738, 0.747) | 1.118 (1.109, 1.127) | 1.097 (1.088, 1.106) | 1.095 (1.086, 1.104) |

| p-value | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | ||||

| Pack-year | ||||||||

| None | 1,306,249 | 488,735 | 10,527,390.24 | 46.4251 | 1 (Ref.) | 1 (Ref.) | 1 (Ref.) | 1 (Ref.) |

| <10 | 194,823 | 52,573 | 1,695,866.69 | 31.0007 | 0.667 (0.661, 0.673) | 0.996 (0.986, 1.006) | 0.996 (0.986, 1.006) | 0.995 (0.985, 1.005) |

| <20 | 231,190 | 60,742 | 2,015,666.62 | 30.1349 | 0.649 (0.643, 0.654) | 1.016 (1.006, 1.026) | 1.013 (1.003, 1.023) | 1.011 (1.001, 1.021) |

| <30 | 194,542 | 52,777 | 1,677,908.99 | 31.454 | 0.677 (0.671, 0.683) | 1.057 (1.046, 1.068) | 1.047 (1.037, 1.058) | 1.045 (1.034, 1.056) |

| <40 | 112,150 | 35,842 | 924,688.79 | 38.7611 | 0.835 (0.826, 0.844) | 1.141 (1.128, 1.155) | 1.127 (1.114, 1.141) | 1.125 (1.112, 1.139) |

| ≥40 | 84,314 | 31,240 | 640,527.06 | 48.7723 | 1.052 (1.040, 1.064) | 1.223 (1.208, 1.238) | 1.208 (1.193, 1.224) | 1.207 (1.191, 1.222) |

| p-value | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | ||||

| N | Event | Duration | IR, per 1000 | HR (95% C.I) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | |||||

| Smoking status and Duration | ||||||||

| None | 1,306,249 | 488,735 | 10,527,390.24 | 46.4251 | 1 (Ref.) | 1 (Ref.) | 1 (Ref.) | 1 (Ref.) |

| Ex and <10 | 50,731 | 13,488 | 445,496.19 | 30.2764 | 0.652 (0.641, 0.663) | 0.981 (0.964, 0.998) | 0.979 (0.962, 0.996) | 0.978 (0.961, 0.995) |

| Ex and <20 | 110,117 | 29,059 | 969,121.1 | 29.9849 | 0.645 (0.638, 0.653) | 1.024 (1.011, 1.037) | 1.008 (0.995, 1.021) | 1.007 (0.994, 1.020) |

| Ex and ≥20 | 179,067 | 59,211 | 1,462,604.32 | 40.4833 | 0.872 (0.865, 0.879) | 1.112 (1.101, 1.123) | 1.093 (1.082, 1.104) | 1.091 (1.080, 1.102) |

| Current and <10 | 25,018 | 7207 | 215,095.1 | 33.5061 | 0.721 (0.704, 0.738) | 1.063 (1.038, 1.088) | 1.058 (1.033, 1.083) | 1.057 (1.032, 1.082) |

| Current and <20 | 72,487 | 17,480 | 645,741.3 | 27.0697 | 0.583 (0.574, 0.592) | 0.994 (0.979, 1.010) | 0.992 (0.977, 1.008) | 0.991 (0.975, 1.006) |

| Current and ≥20 | 379,599 | 106,729 | 3,216,600.13 | 33.1807 | 0.714 (0.709, 0.719) | 1.066 (1.057, 1.075) | 1.066 (1.057, 1.075) | 1.065 (1.056, 1.074) |

| Smoking status and amount | ||||||||

| None | 1,306,249 | 488,735 | 10,527,390.24 | 46.4251 | 1 (Ref.) | 1 (Ref.) | 1 (Ref.) | 1 (Ref.) |

| Ex and <10 | 40,665 | 12,027 | 345,340.08 | 34.8265 | 0.750 (0.736, 0.763) | 0.993 (0.975, 1.011) | 0.998 (0.979, 1.016) | 0.997 (0.979, 1.016) |

| Ex and <20 | 128,117 | 35,973 | 1,105,256.62 | 32.5472 | 0.700 (0.693, 0.708) | 1.011 (0.999, 1.023) | 1.007 (0.995, 1.019) | 1.006 (0.994, 1.017) |

| Ex and ≥20 | 171,133 | 53,758 | 1,426,624.91 | 37.6819 | 0.811 (0.804, 0.819) | 1.132 (1.120, 1.143) | 1.100 (1.089, 1.111) | 1.097 (1.086, 1.109) |

| Current and <10 | 46,411 | 13,905 | 381,732.79 | 36.426 | 0.784 (0.771, 0.798) | 1.004 (0.987, 1.021) | 1.015 (0.998, 1.033) | 1.015 (0.997, 1.032) |

| Current and <20 | 172,897 | 45,942 | 1,489,995.14 | 30.8337 | 0.664 (0.657, 0.670) | 1.007 (0.996, 1.018) | 1.017 (1.006, 1.028) | 1.016 (1.005, 1.027) |

| Current and ≥20 | 257,796 | 71,569 | 2,205,708.61 | 32.4472 | 0.698 (0.693, 0.704) | 1.107 (1.097, 1.118) | 1.095 (1.084, 1.105) | 1.092 (1.082, 1.103) |

| Smoking status and Pack-year | ||||||||

| None | 1,306,249 | 488,735 | 10,527,390.24 | 46.4251 | 1 (Ref.) | 1 (Ref.) | 1 (Ref.) | 1 (Ref.) |

| Ex and <10 | 112,688 | 30,325 | 985,606.07 | 30.7679 | 0.662 (0.655, 0.670) | 0.988 (0.976, 1.000) | 0.987 (0.974, 0.999) | 0.986 (0.973, 0.998) |

| Ex and <20 | 99,797 | 28,095 | 861,820.86 | 32.5996 | 0.702 (0.693, 0.710) | 1.043 (1.029, 1.056) | 1.027 (1.014, 1.041) | 1.025 (1.012, 1.039) |

| Ex and ≥20 | 127,430 | 43,338 | 1,029,794.68 | 42.0841 | 0.907 (0.898, 0.916) | 1.155 (1.142, 1.168) | 1.126 (1.113, 1.139) | 1.123 (1.111, 1.136) |

| Current and <10 | 82,135 | 22,248 | 710,260.62 | 31.3237 | 0.674 (0.665, 0.683) | 1.008 (0.995, 1.022) | 1.011 (0.997, 1.026) | 1.010 (0.996, 1.025) |

| Current and <20 | 131,393 | 32,647 | 1,153,845.75 | 28.2941 | 0.609 (0.603, 0.616) | 0.995 (0.983, 1.007) | 1.002 (0.990, 1.014) | 1.000 (0.988, 1.013) |

| Current and ≥20 | 263,576 | 76,521 | 2,213,330.16 | 34.5728 | 0.744 (0.738, 0.750) | 1.103 (1.093, 1.113) | 1.098 (1.088, 1.109) | 1.097 (1.087, 1.107) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ryu, J.-H.; Kim, K.-W.; Kim, J.-Y. Long-Term and Heavy Smoking as a Risk Factor for Lumbar Spinal Stenosis: Evidence from a Large-Scale, Nationwide Population-Based Cohort. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 7691. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14217691

Ryu J-H, Kim K-W, Kim J-Y. Long-Term and Heavy Smoking as a Risk Factor for Lumbar Spinal Stenosis: Evidence from a Large-Scale, Nationwide Population-Based Cohort. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(21):7691. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14217691

Chicago/Turabian StyleRyu, Ji-Hyun, Ki-Won Kim, and Ju-Yeong Kim. 2025. "Long-Term and Heavy Smoking as a Risk Factor for Lumbar Spinal Stenosis: Evidence from a Large-Scale, Nationwide Population-Based Cohort" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 21: 7691. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14217691

APA StyleRyu, J.-H., Kim, K.-W., & Kim, J.-Y. (2025). Long-Term and Heavy Smoking as a Risk Factor for Lumbar Spinal Stenosis: Evidence from a Large-Scale, Nationwide Population-Based Cohort. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(21), 7691. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14217691