Prediction of Non-Cardiac Organ Failure in Acute Myocardial Infarction Patients with Arrhythmia: A Retrospective Case–Control Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants Enrollment

2.2. Data Collection and Grouping

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

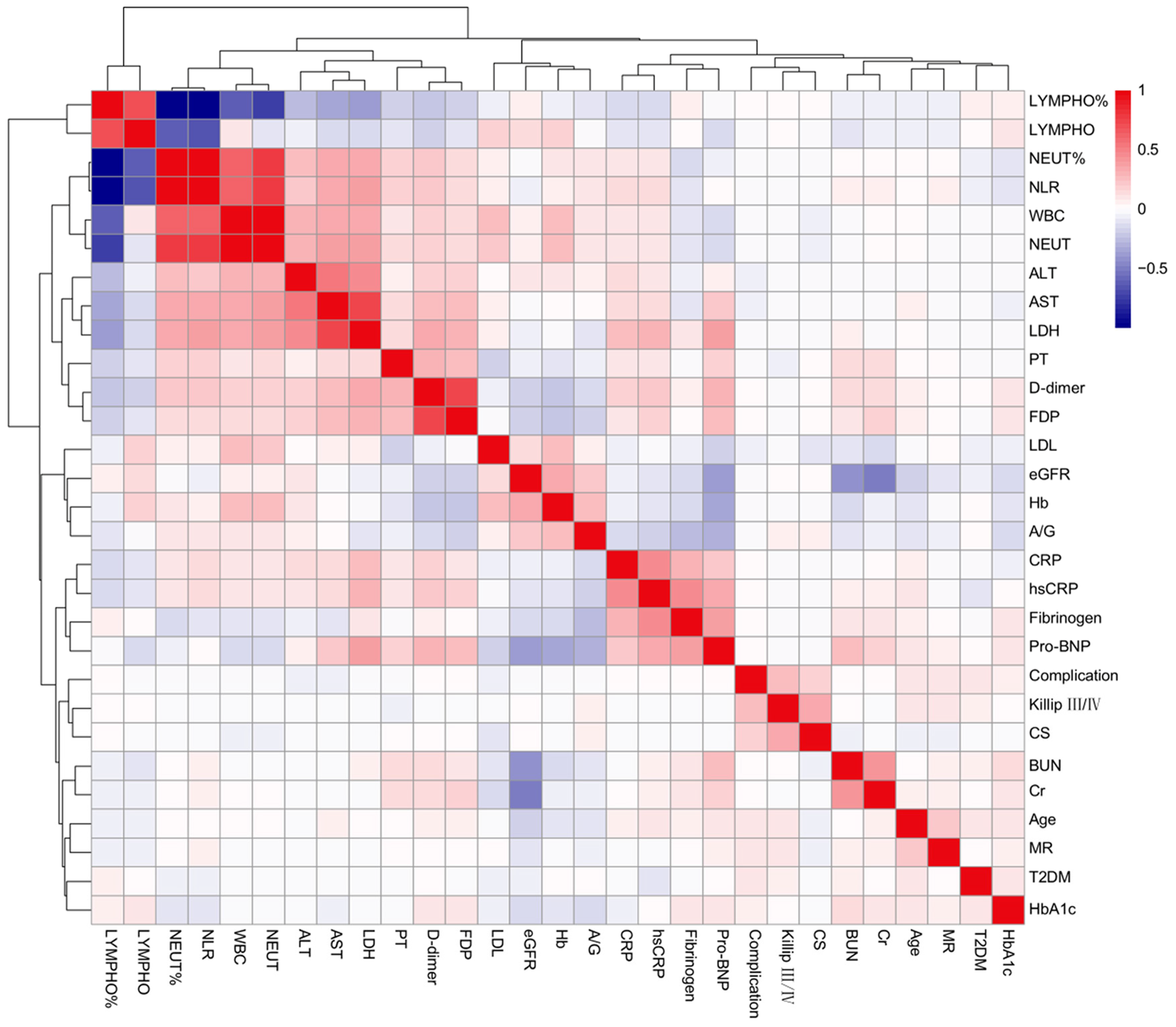

3.1. Baseline Characteristics

3.2. LASSO-Logistic and Multivariate Logistic Regression Results

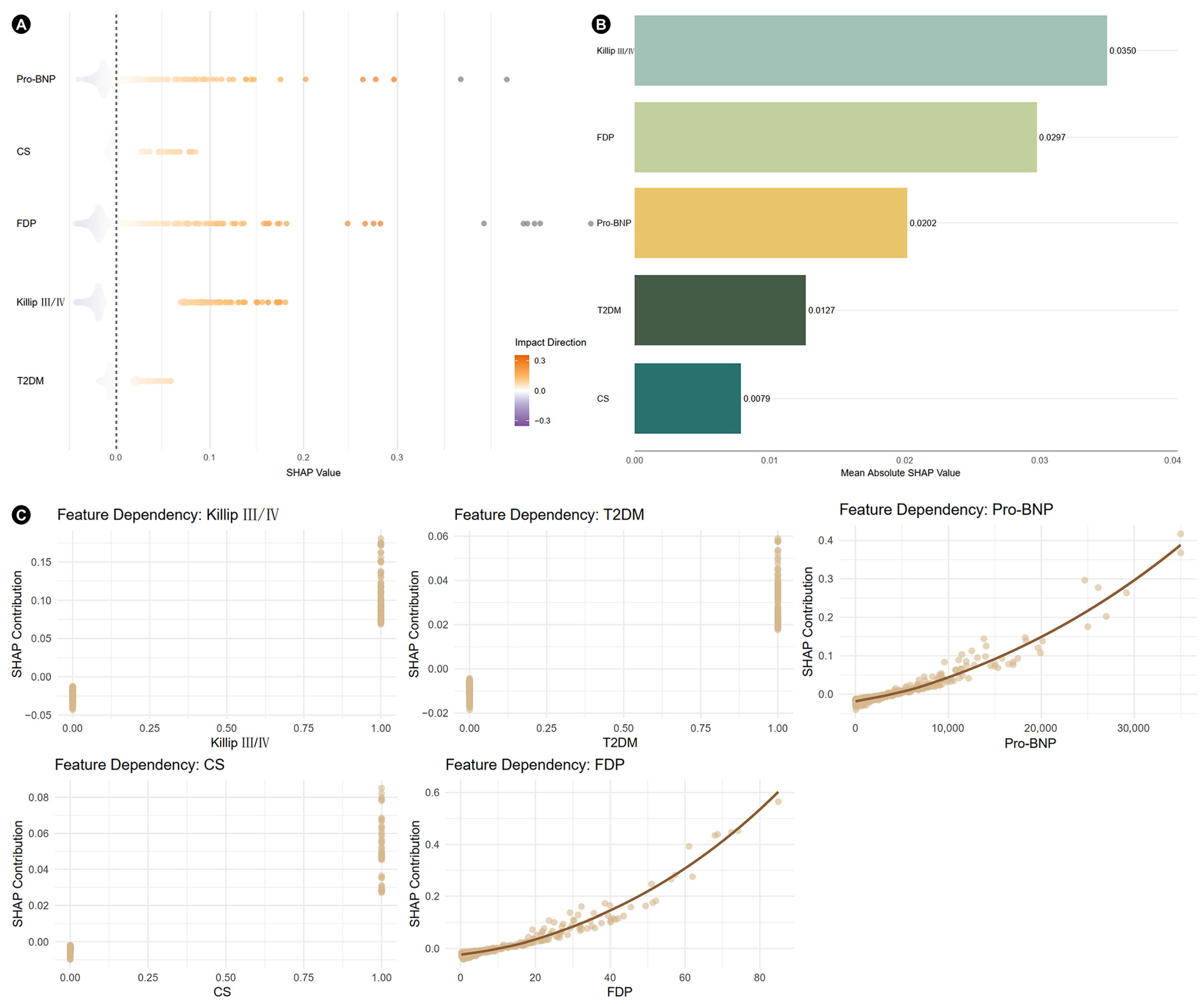

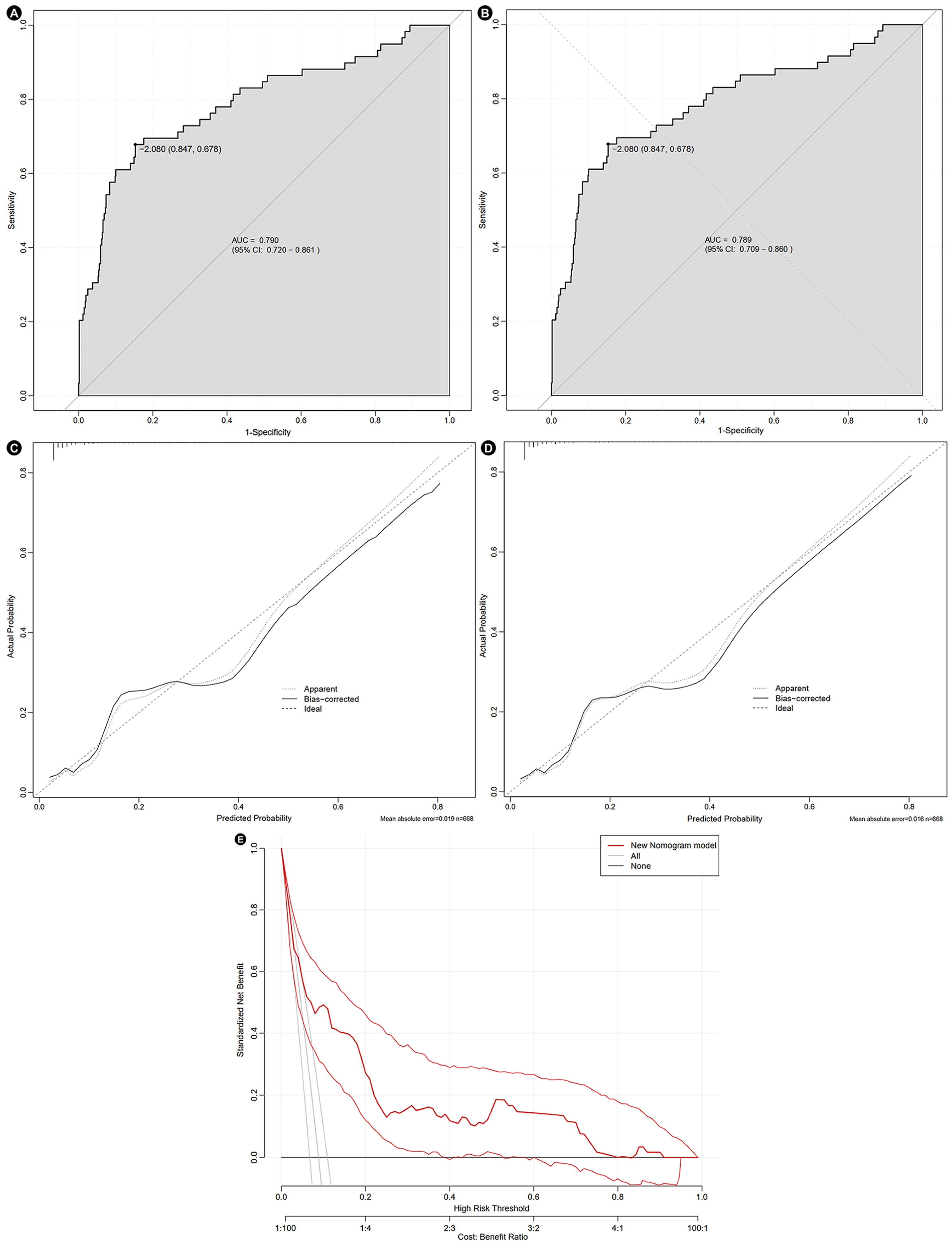

3.3. SHAP Analysis and Construction of Nomogram

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AMI | Acute myocardial infarction |

| AKI | Acute kidney injury |

| AUC | Area under the curve |

| CI | Confidence interval |

| CS | Cardiogenic shock |

| FDP | Fibrin degradation products |

| LASSO | Least absolute shrinkage and selection operator |

| OR | Odds ratio |

| Pro-BNP | Pro-brain natriuretic peptide |

| SHAP | Shapley additive explanations |

| T2DM | Type 2 diabetes mellitus |

| VF | Ventricular fibrillation |

References

- Jaiswal, S.; Libby, P. Clonal haematopoiesis: Connecting ageing and inflammation in cardiovascular disease. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2020, 17, 137–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frampton, J.; Ortengren, A.R.; Zeitler, E.P. Arrhythmias After Acute Myocardial Infarction. Yale J. Biol. Med. 2023, 96, 83–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaur, U.; Gadkari, C.; Pundkar, A. Associated Factors and Mortality of Arrhythmia in Emergency Department: A Narrative Review. Cureus 2024, 16, e68645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, W.T.; Montrief, T.; Koyfman, A.; Long, B. Dysrhythmias and heart failure complicating acute myocardial infarction: An emergency medicine review. Am. J. Emerg. Med. 2019, 37, 1554–1561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurmi, P.; Patidar, A.; Patidar, S.; Yadav, U. Incidence and Prognostic Significance of Arrhythmia in Acute Myocardial Infarction Presentation: An Observational Study. Cureus 2024, 16, e71564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garcia, R.; Marijon, E.; Karam, N.; Narayanan, K.; Anselme, F.; Césari, O.; Champ-Rigot, L.; Manenti, V.; Martins, R.; Puymirat, E.; et al. Ventricular fibrillation in acute myocardial infarction: 20-year trends in the FAST-MI study. Eur. Heart J. 2022, 43, 4887–4896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alnsasra, H.; Tsaban, G.; Weinstein, J.M.; Nasasra, M.; Ovdat, T.; Beigel, R.; Orvin, K.; Haim, M. Sex differences in ventricular arrhythmia, atrial fibrillation and atrioventricular block complicating acute myocardial infarction. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2023, 10, 1217525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehta, C.; Shin, A.; Osorio, B.; DePolo, D.; Vargas, I.; Hao, E.; Khan, A.; Chandragiri, S.; Shringi, S.; Diaz, P.O.M.; et al. Management of non-Cardiac Organ Failure in cardiogenic shock. Am. Heart J. Plus 2025, 55, 100549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Montrief, T.; Davis, W.T.; Koyfman, A.; Long, B. Mechanical, inflammatory, and embolic complications of myocardial infarction: An emergency medicine review. Am. J. Emerg. Med. 2019, 37, 1175–1183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kellum, J.A.; Lameire, N. Diagnosis, evaluation, and management of acute kidney injury: A KDIGO summary (Part 1). Crit Care 2013, 17, 204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flamm, S.L.; Wong, F.; Ahn, J.; Kamath, P.S. AGA Clinical Practice Update on the Evaluation and Management of Acute Kidney Injury in Patients With Cirrhosis: Expert Review. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2022, 20, 2707–2716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shingina, A.; Mukhtar, N.; Wakim-Fleming, J.; Alqahtani, S.; Wong, R.J.; Limketkai, B.N.; Larson, A.M.; Grant, L. Acute Liver Failure Guidelines. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2023, 118, 1128–1153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matthay, M.A.; Arabi, Y.; Arroliga, A.C.; Bernard, G.; Bersten, A.D.; Brochard, L.J.; Calfee, C.S.; Combes, A.; Daniel, B.M.; Ferguson, N.D.; et al. A New Global Definition of Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2024, 209, 37–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuźma, Ł.; Małyszko, J.; Kurasz, A.; Niwińska, M.M.; Zalewska-Adamiec, M.; Bachórzewska-Gajewska, H.; Dobrzycki, S. Impact of renal function on patients with acute coronary syndromes: 15,593 patient-years study. Ren. Fail. 2020, 42, 881–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakashima, M.; Nakamura, K.; Nishihara, T.; Ichikawa, K.; Nakayama, R.; Takaya, Y.; Toh, N.; Akagi, S.; Miyoshi, T.; Akagi, T.; et al. Association between Cardiovascular Disease and Liver Disease, from a Clinically Pragmatic Perspective as a Cardiologist. Nutrients 2023, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marenzi, G.; Cosentino, N.; Bartorelli, A.L. Acute kidney injury in patients with acute coronary syndromes. Heart 2015, 101, 1778–1785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandroni, C.; Cronberg, T.; Sekhon, M. Brain injury after cardiac arrest: Pathophysiology, treatment, and prognosis. Intensive Care Med. 2021, 47, 1393–1414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chalikias, G.; Serif, L.; Kikas, P.; Thomaidis, A.; Stakos, D.; Makrygiannis, D.; Chatzikyriakou, S.; Papoulidis, N.; Voudris, V.; Lantzouraki, A.; et al. Long-term impact of acute kidney injury on prognosis in patients with acute myocardial infarction. Int. J. Cardiol. 2019, 283, 48–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Long, Y.; Tong, Y.; Wu, Y.; Wang, H.; Liu, C.; Qu, K.; Li, G. Interaction between Acute Hepatic Injury and Early Coagulation Dysfunction on Mortality in Patients with Acute Myocardial Infarction. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 1534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaur, J.; Bhardwaj, N.; Reddy, S.; D’Cruz, S. Acute Kidney Injury in Acute Myocardial Infarction and Its Outcome at 3 and 6 Months. Saudi J. Kidney Dis. Transplant. 2023, 34, 297–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Horton, W.B.; Barrett, E.J. Microvascular Dysfunction in Diabetes Mellitus and Cardiometabolic Disease. Endocr. Rev. 2021, 42, 29–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demir, S.; Nawroth, P.P.; Herzig, S.; Üstünel, B.E. Emerging Targets in Type 2 Diabetes and Diabetic Complications. Adv. Sci. 2021, 8, 2100275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Figueroa-Triana, J.F.; Mora-Pabón, G.; Quitian-Moreno, J.; Álvarez-Gaviria, M.; Idrovo, C.; Cabrera, J.S.; Peñuela, J.A.R.; Caballero, Y.; Naranjo, M. Acute myocardial infarction with right bundle branch block at presentation: Prevalence and mortality. J. Electrocardiol. 2021, 66, 38–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, C.; Chen, F.; Liu, L.; Ge, Z.; Feng, C.; Chen, Y. Impact of diabetes on outcomes of cardiogenic shock: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Diab Vasc. Dis. Res. 2022, 19, 14791641221132242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, X.; Wang, D.; Jin, Y.; Gong, M.; Lin, Q.; He, Y.; Huang, W.; Shan, P.; Liang, D. Sex differences in the association between D-dimer and the incidence of acute kidney injury in patients admitted with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction: A retrospective observational study. Intern. Emerg. Med. 2024, 19, 91–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Hao, Y. The correlation of the peripheral blood NT-proBNP and NF-κB expression levels with the myocardial infarct area and the post-treatment no-reflow in acute myocardial infarction patients. Am. J. Transl. Res. 2021, 13, 4561–4572. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, Y.; Zheng, J.; Zhou, W.; Luo, Z.; Jiang, W. Predictive value of perioperative NT-proBNP levels for acute kidney injury in patients with compromised renal function undergoing cardiac surgery: A case control study. BMC Anesthesiol. 2024, 24, 298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Items | Total (n = 668) | Complication Group (n = 59) | Control Group (n = 609) | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 67 (57, 74) | 70 (60, 76) | 66 (57, 73) | 0.018 |

| Gender (male, %) | 514 (76.9) | 42 (71.2) | 472 (77.5) | 0.271 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 24.45 (22.29, 26.01) | 24.42 (21.13, 26.43) | 24.45 (22.49, 25.97) | 0.510 |

| Smoking (%) | 201 (30.1) | 22 (37.3) | 179 (29.4) | 0.207 |

| Drinking (%) | 71 (10.6) | 4 (6.8) | 67 (11.0) | 0.315 |

| STEMI (%) | 391 (5835) | 36 (61.0) | 355 (58.3) | 0.685 |

| Killip III/IV (%) | 115 (17.2) | 28 (47.5) | 87 (14.3) | <0.001 |

| Comorbidities (%) | ||||

| Hypertension | 511 (76.5) | 49 (83.1) | 462 (75.9) | 0.214 |

| T2DM | 154 (23.1) | 22 (37.3) | 132 (21.7) | 0.007 |

| CS | 52 (7.8) | 13 (22.0) | 39 (6.4) | <0.001 |

| Previous AF | 37 (5.5) | 4 (6.8) | 33 (5.4) | 0.890 |

| Arrhythmia (%) | ||||

| Sinus bradycardia | 34 (5.1) | 1 (1.7) | 33 (5.4) | 0.350 |

| Atrial flutter | 23 (3.4) | 3 (5.1) | 20 (3.3) | 0.447 |

| AF | 300 (44.9) | 31 (52.5) | 269 (44.2) | 0.217 |

| Supraventricular tachycardia | 35 (5.2) | 2 (3.4) | 33 (5.4) | 0.760 |

| PVC | 165 (14.7) | 10 (16.9) | 155 (25.5) | 0.148 |

| Ventricular tachycardia | 116 (17.4) | 13 (22.0) | 103 (16.9) | 0.321 |

| VF | 77 (11.5) | 7 (11.9) | 70 (11.5) | 0.932 |

| Atrioventricular block | 107 (16.0) | 11 (18.6) | 96 (15.8) | 0.565 |

| Biochemical results | ||||

| Hb (g/L) | 139.00 (127.00, 150.00) | 132.00 (116.00, 143.00) | 140.00 (128.00, 150.00) | 0.003 |

| WBC (109/L) | 9.06 (6.87, 12.11) | 9.95 (7.34, 15.02) | 8.92 (6.83, 11.99) | 0.044 |

| NEUT (109/L) | 6.96 (4.73, 9.94) | 8.54 (5.49, 12.55) | 6.90 (4.66, 9.83) | 0.015 |

| NEUT% (%) | 77.00 (69.50, 85.48) | 83.50 (71.70, 89.10) | 76.70(69.30, 85.10) | 0.006 |

| LYMPHO (109/L) | 1.32 (0.96, 1.80) | 1.10 (0.76, 1.60) | 1.33 (0.99, 1.82) | 0.008 |

| LYMPHO% (%) | 15.69 (9.42, 22.16) | 11.21 (6.29, 20.39) | 15.88 (9.72, 22.23) | 0.003 |

| NLR | 4.93(3.18, 9.09) | 7.45 (3.41, 13.97) | 4.78 (3.17, 8.77) | 0.003 |

| CRP (mg/L) | 16.10 (10.00, 45.73) | 21.27 (10.00, 73.40) | 15.83 (10.00, 44.07) | 0.077 |

| hs-CRP (mg/L) | 4.48 (1.55, 9.55) | 7.64 (2.24, 10.00) | 4.31 (1.52, 9.43) | 0.020 |

| HbA1c (%) | 5.94 (5.60, 6.80) | 6.20 (5.70, 7.79) | 5.90 (5.60, 6.66) | 0.054 |

| ALT (U/L) | 33.00 (22.00, 56.00) | 52.00 (22.00, 119.00) | 33.00 (22.00, 53.46) | 0.003 |

| AST (U/L) | 47.85 (27.00, 114.00) | 70.00 (27.00, 201.00) | 47.00 (27.00, 109.29) | 0.077 |

| Total protein (g/L) | 62.65 (58.55, 67.10) | 62.30 (58.30, 67.40) | 62.70 (58.60, 67.10) | 0.824 |

| Albumin (g/L) | 37.30 ± 4.82 | 36.29 ± 4.48 | 37.40 ± 4.85 | 0.104 |

| Globulin (g/L) | 25.50 (23.20, 28.10) | 26.50 (23.50, 29.40) | 25.40 (23.10, 28.00) | 0.183 |

| A/G | 1.44 (1.28, 1.65) | 1.37 (1.17, 1.48) | 1.44 (1.29, 1.66) | 0.007 |

| eGFR (mL/min/1.73 m2) | 87.80 (71.57, 99.36) | 59.65 (38.81, 79.18) | 89.00 (74.68, 99.97) | <0.001 |

| Cr (umol/L) | 69.00 (57.00, 84.00) | 98.00 (78.00, 130.00) | 68.00 (56.00, 80.50) | <0.001 |

| BUN (mmol/L) | 6.06 (4.85, 7.48) | 9.04 (6.09, 14.36) | 6.00 (4.77, 7.23) | <0.001 |

| LDL (mmol/L) | 2.15 (1.60, 2.72) | 1.91 (1.43, 2.63) | 2.17 (1.64, 2.73) | 0.063 |

| HDL (mmol/L) | 0.94 (0.81, 1.10) | 0.92 (0.80, 1.10) | 0.95 (0.81, 1.10) | 0.889 |

| TG (mmol/L) | 1.07 (0.77, 1.54) | 0.97 (0.63, 1.72) | 1.08 (0.79, 1.54) | 0.235 |

| TC (mmol/L) | 3.81 (3.13, 4.53) | 3.59 (2.98, 4.38) | 3.82 (3.16, 4.55) | 0.206 |

| APTT (s) | 31.70 (27.20, 37.90) | 31.90 (26.65, 38.30) | 31.70 (27.20, 37.88) | 0.943 |

| PT (s) | 13.45 (12.40, 14.40) | 14.10 (11.70, 15.90) | 13.40 (12.40, 14.40) | 0.073 |

| Fibrinogen (g/L) | 3.23 (2.57, 4.13) | 3.38 (2.78, 4.73) | 3.2 (2.57, 4.07) | 0.080 |

| D-dimer (mg/L) | 0.68 (0.40, 1.67) | 1.27 (0.50, 3.63) | 0.64 (0.40, 1.54) | 0.001 |

| FDP (mg/L) | 2.48 (1.40, 6.89) | 5.40 (1.73, 18.12) | 2.40 (1.37, 6.29) | 0.001 |

| LDH (U/L) | 298.00 (229.25, 468.00) | 352.00 (262.00, 831.00) | 296.00 (225.00, 454.50) | 0.012 |

| CK-MB (U/L) | 28.00 (15.00, 81.00) | 27.00 (15.00, 106.10) | 28.00 (15.00, 80.75) | 0.706 |

| CK (U/L) | 234.00 (99.00, 786.00) | 254.00 (105.00, 939.00) | 232.00 (97.75, 776.25) | 0.652 |

| hs-cTnT (ng/mL) | 0.56 (0.10, 2.32) | 0.84 (0.13, 2.99) | 0.54 (0.09, 2.31) | 0.200 |

| Pro-BNP (pg/mL) | 1302.50 (373.50, 3476.00) | 3451.02 (1382.00, 10,783.00) | 1170.00 (340.20, 3159.00) | <0.001 |

| Echo cardiology | ||||

| LVEF (%) | 48.00 (42.00, 59.00) | 45.00 (43.00, 51.75) | 48.50 (42.00, 59.00) | 0.396 |

| MR (%) | 144 (21.6) | 22 (37.3) | 122 (20.0) | 0.002 |

| PAH (%) | 63 (9.4) | 7 (11.9) | 56 (9.2) | 0.503 |

| In-hospital outcomes | ||||

| PCI (%) | 555 (83.1) | 46 (78.0) | 509 (83.6) | 0.272 |

| IABP (%) | 46 (6.9) | 11 (18.6) | 35 (5.7) | 0.001 |

| ECMO (%) | 13 (1.9) | 6 (10.2) | 7 (1.1) | <0.001 |

| Length of hospital stay (days) | 4 (3, 7) | 6 (4, 8) | 4 (3, 6) | <0.001 |

| In-hospital mortality (%) | 16 (2.4) | 4 (6.8) | 12 (2.0) | 0.063 |

| Items | LASSO-Logistic Regression | Multivariate Logistic Regression | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Assignment | Coefficient | OR (95% CI) | p Value | |

| Age (years) | Male = 1, Famale = 0 | 0.2365 | 1.014 (0.985, 1.043) | 0.359 |

| Killip III/IV (%) | Yes = 1, No = 0 | 0.3987 | 2.409 (1.246, 4.657) | 0.009 |

| T2DM (%) | Yes = 1, No = 0 | 0.2703 | 1.888 (1.005, 3.546) | 0.048 |

| CS (%) | Yes = 1, No = 0 | 0.4426 | 3.443 (1.463, 8.089) | 0.005 |

| Hb (g/L) | Continuous variable | |||

| WBC (109/L) | Continuous variable | |||

| NEUT (109/L) | Continuous variable | |||

| NEUT% (%) | Continuous variable | |||

| LYMPHO (109/L) | Continuous variable | |||

| LYMPHO% (%) | Continuous variable | |||

| NLR | Continuous variable | 0.2637 | 1.027 (0.988, 1.068) | 0.177 |

| CRP (mg/L) | Continuous variable | 0.1335 | 1.002 (0.995, 1.010) | 0.541 |

| hs-CRP (mg/L) | Continuous variable | |||

| HbA1c (%) | Continuous variable | |||

| A/G | Continuous variable | |||

| ALT (U/L) | Continuous variable | |||

| AST (U/L) | Continuous variable | |||

| eGFR (mL/min/1.73 m2) | Continuous variable | |||

| Cr (umol/L) | Continuous variable | |||

| BUN (mmol/L) | Continuous variable | |||

| LDL (mmol/L) | Continuous variable | |||

| PT (s) | Continuous variable | 0.2134 | 0.967 (0.867, 1.078) | 0.545 |

| Fibrinogen (g/L) | Continuous variable | 0.0859 | 1.081 (0.862, 1.354) | 0.501 |

| D-dimer (mg/L) | Continuous variable | |||

| FDP (mg/L) | Continuous variable | −0.2991 | 1.029 (1.009, 1.049) | 0.003 |

| LDH (U/L) | Continuous variable | |||

| Pro-BNP (pg/mL) | Continuous variable | 0.0180 | 1.000 (1.000, 1.000) | 0.002 |

| MR (%) | Yes = 1, No = 0 | 0.3813 | 1.809 (0.925, 3.537) | 0.083 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yan, L.; Zhang, B.; Chen, B.; Yan, Y.; Shi, T. Prediction of Non-Cardiac Organ Failure in Acute Myocardial Infarction Patients with Arrhythmia: A Retrospective Case–Control Study. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 7667. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14217667

Yan L, Zhang B, Chen B, Yan Y, Shi T. Prediction of Non-Cardiac Organ Failure in Acute Myocardial Infarction Patients with Arrhythmia: A Retrospective Case–Control Study. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(21):7667. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14217667

Chicago/Turabian StyleYan, Luqin, Bowen Zhang, Boyu Chen, Yang Yan, and Tao Shi. 2025. "Prediction of Non-Cardiac Organ Failure in Acute Myocardial Infarction Patients with Arrhythmia: A Retrospective Case–Control Study" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 21: 7667. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14217667

APA StyleYan, L., Zhang, B., Chen, B., Yan, Y., & Shi, T. (2025). Prediction of Non-Cardiac Organ Failure in Acute Myocardial Infarction Patients with Arrhythmia: A Retrospective Case–Control Study. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(21), 7667. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14217667