Improvement in Depressive Symptoms Is Not Associated with the Severity of Autobiographical Amnesia Following Electroconvulsive Therapy—A Preliminary Report from Naturalistic Prospective Observational Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Psychometric Evaluation and Data Collection

2.3. Sample Size Calculation

2.4. Statistical Analysis

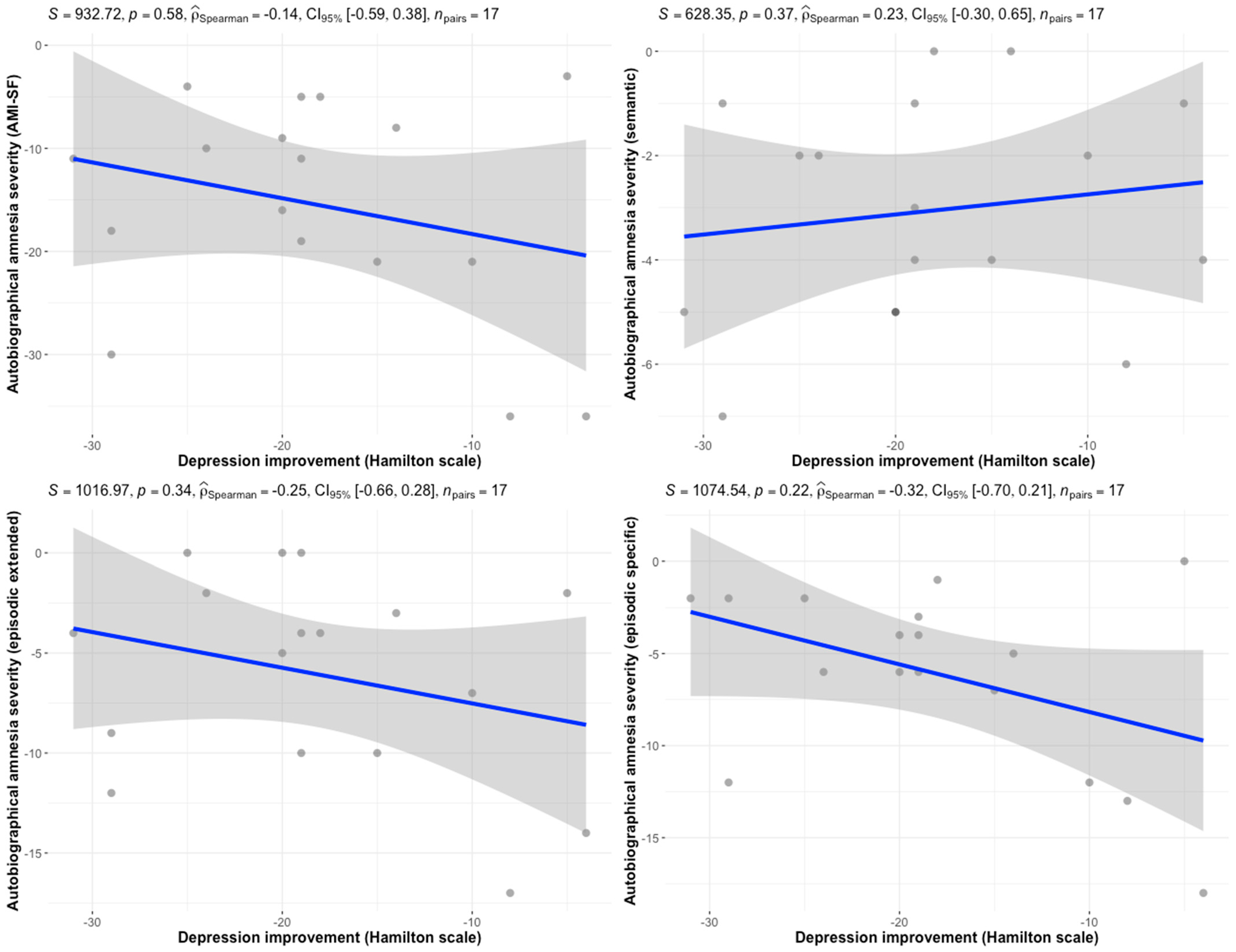

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AMI-SF | Autobiographical Memory Inventory—Short Form |

| BL | Bilateral |

| ECT | Electroconvulsive Therapy |

| RAA | Retrograde Autobiographical Amnesia |

| RUL | Right Unilateral |

| TRD | Treatment-resistant Depression |

References

- Leiknes, K.A.; Jarosh-von Schweder, L.; Høie, B. Contemporary use and practice of electroconvulsive therapy worldwide. Brain Behav. 2012, 2, 283–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sackeim, H.A.; Dillingham, E.M.; Prudic, J.; Cooper, T.; McCall, W.V.; Rosenquist, P.; Isenberg, K.; Garcia, K.; Mulsant, B.H.; Haskett, R.F. Effect of concomitant pharmacotherapy on electroconvulsive therapy outcomes: Short-term efficacy and adverse effects. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 2009, 66, 729–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCall, W.V.; Reboussin, D.; Prudic, J.; Haskett, R.F.; Isenberg, K.; Olfson, M.; Rosenquist, P.B.; Sackeim, H.A. Poor health-related quality of life prior to ect in depressed patients normalizes with sustained remission after ect. J. Affect. Disord. 2013, 147, 107–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stachura, A. Retrograde Autobiographical Amnesia Following Electroconvulsive Therapy (ECT) in Patients Treated for Depression-A Mixed-Methods Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Master’s Thesis, University of Oxford, Oxford, UK, 2024. Available online: https://osf.io/preprints/thesiscommons/uc29a_v1 (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Squire, L.R.; Wetzel, C.D.; Slater, P.C. Memory complaint after electroconvulsive therapy: Assessment with a new self-rating instrument. Biol. Psychiatry 1979, 14, 791–801. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Philpot, M.; Collins, C.; Trivedi, P.; Treloar, A.; Gallacher, S.; Rose, D. Eliciting users’ views of ect in two mental health trusts with a user-designed questionnaire. J. Ment. Health 2004, 13, 403–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammar, Å.; Ronold, E.H.; Spurkeland, M.A.; Ueland, R.; Kessler, U.; Oedegaard, K.J.; Oltedal, L. Improvement of persistent impairments in executive functions and attention following electroconvulsive therapy in a case control longitudinal follow up study. BMC Psychiatry 2024, 24, 832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderson, I.M.; McAllister-Williams, R.H.; Downey, D.; Elliott, R.; Loo, C. Cognitive function after electroconvulsive therapy for depression: Relationship to clinical response. Psychol. Med. 2021, 51, 1647–1656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loef, D.; Hoogendoorn, A.W.; Somers, M.; Mocking, R.J.T.; Scheepens, D.S.; Scheepstra, K.W.F.; Blijleven, M.; Hegeman, J.M.; van den Berg, K.S.; Schut, B.; et al. A prediction model for electroconvulsive therapy effectiveness in patients with major depressive disorder from the dutch ect consortium (dec). Mol. Psychiatry 2025, 30, 1915–1924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McIntyre, R.S.; Alsuwaidan, M.; Baune, B.T.; Berk, M.; Demyttenaere, K.; Goldberg, J.F.; Gorwood, P.; Ho, R.; Kasper, S.; Kennedy, S.H.; et al. Treatment-resistant depression: Definition, prevalence, detection, management, and investigational interventions. World Psychiatry 2023, 22, 394–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abrams, R. Stimulus titration and ect dosing. J. ECT 2002, 18, 3–9; discussion 14–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, R.S.; Bachu, A.; Youssef, N.A. Combination of lithium and electroconvulsive therapy (ect) is associated with higher odds of delirium and cognitive problems in a large national sample across the united states. Brain Stimul. 2020, 13, 15–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McElhiney, M.; Moody, B.; Sackeim, H. The Autobiographical Memory Interview-Short Form; New York State Psychiatric Institute: New York, NY, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton, M. A rating scale for depression. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 1960, 23, 56–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semkovska, M.; Noone, M.; Carton, M.; McLoughlin, D.M. Measuring consistency of autobiographical memory recall in depression. Psychiatry Res. 2012, 197, 41–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faul, F.; Erdfelder, E.; Lang, A.G.; Buchner, A. G*power 3: A flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behav. Res. Methods 2007, 39, 175–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kolshus, E.; Jelovac, A.; McLoughlin, D.M. Bitemporal v. High-dose right unilateral electroconvulsive therapy for depression: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Psychol. Med. 2017, 47, 518–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frais, A.T. Electroconvulsive therapy: A theory for the mechanism of action. J. ECT 2010, 26, 60–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frank Koopowitz, L.; Frank Koopowitz, L.; Chur-Hansen, A.; Reid, S.; Blashki, M. The subjective experience of patients who received electroconvulsive therapy. Aust. N. Z. J. Psychiatry 2003, 37, 49–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vamos, M. The cognitive side effects of modern ect: Patient experience or objective measurement? J. ECT 2008, 24, 18–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, D.M.; Gálvez, V.; Loo, C.K. Predicting retrograde autobiographical memory changes following electroconvulsive therapy: Relationships between individual, treatment, and early clinical factors. Int. J. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2015, 18, pyv067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barreiros, A.R.; Massaneda-Tuneu, C.; Waite, S.; Sarma, S.; Branjerdporn, G.; Zeng, C.; Dong, V.; Loo, C.; Martin, D.M. The effects of treatment, clinical and demographic factors on recovery of orientation after ect: A care network study. J. Affect. Disord. 2025, 368, 337–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Richard-Devantoy, S.; Berlim, M.T.; Jollant, F. Suicidal behaviour and memory: A systematic review and meta-analysis. World J. Biol. Psychiatry 2015, 16, 544–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chu, C.; Podlogar, M.C.; Rogers, M.L.; Buchman-Schmitt, J.M.; Negley, J.H.; Joiner, T.E. Does suicidal ideation influence memory? A study of the role of violent daydreaming in the relationship between suicidal ideation and everyday memory. Behav. Modif. 2016, 40, 731–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Porter, R.J.; Baune, B.T.; Morris, G.; Hamilton, A.; Bassett, D.; Boyce, P.; Hopwood, M.J.; Mulder, R.; Parker, G.; Singh, A.B.; et al. Cognitive side-effects of electroconvulsive therapy: What are they, how to monitor them and what to tell patients. BJPsych Open 2020, 6, e40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variable | Sample Size (n = 20) Mean ± SD or n (%) |

|---|---|

| Age (years) | 49.1 ± 20.2 |

| Sex | |

| Male | 4 (20) |

| Female | 16 (80) |

| Psychotic symptoms | 7 (35) |

| Suicidal ideation | 8 (40) |

| Depression type | |

| Unipolar | 14 (70) |

| Bipolar | 6 (30) |

| Number of previous depressive episodes | |

| None | 4 (20) |

| 1–3 | 7 (35) |

| >4 | 9 (45) |

| Duration of current episode (months) | 10.3 ± 8.6 |

| Education | |

| Primary | 1 (5) |

| Secondary | 6 (30) |

| Higher | 13 (65) |

| Occupational status | |

| Unemployed | 2 (10) |

| Employed | 10 (50) |

| Disability pension | 3 (15) |

| Retired | 5 (25) |

| Any personality disorder | 3 (15) |

| Baseline depression severity score | 27.2 ± 6.6 |

| Baseline AMI-SF score | 48.2 ± 7.2 |

| ECT type | |

| Unilateral | 15 (75) * |

| Bilateral | 4 (20) |

| Mixed placement | 1 (5) |

| Number of ECT sessions | 10.8 ± 2.3 |

| Mean charge per session (mC) | 387.9 ± 187.1 |

| RUL (n = 15) | BL (n = 5) | p-Value | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre | Post | MD (95% CI) | Pre | Post | MD (95% CI) | ||

| AMI-SF total | 49.3 ± 6.1 | 36.2 ± 10.8 | −13.1 (−18.8 to −7.5) | 44.8 ± 9.8 | 27.4 ± 9.7 | −17.4 (−31.1 to −3.7) | 0.2 |

| Semantic memory | 15.3 ± 2.9 | 13 ± 3.1 | −2.3 (−3.5 to −1.1) | 14.4 ± 2.6 | 10.4 ± 1.5 | −4 (−5.9 to −2.0) | 0.1 |

| Episodic extended memory | 15.7 ± 4.3 | 10.9 ± 5.3 | −4.8 (−7.3 to −2.3) | 13.6 ± 4.3 | 6.2 ± 5.6 | −7.4 (−15 to 0.23) | 0.33 |

| Episodic specific memory | 18.3 ± 1.8 | 12.6 ± 5.2 | −5.7 (−8.4 to −2.9) | 16.8 ± 5.2 | 10.8 ± 5.3 | −6 (−11.4 to −0.7) | 0.72 |

| AMI-SF | Semantic Memory | Episodic Extended | Episodic Specific | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | r | p-Value | r | p-Value | r | p-Value | r | p-Value |

| Age | 0.21 | 0.38 | 0.06 | 0.79 | 0.19 | 0.4 | 0.14 | 0.57 |

| Episode duration | 0.11 | 0.67 | 0.19 | 0.42 | 0 | 0.97 | 0.2 | 0.4 |

| Baseline depression severity | −0.28 | 0.28 | −0.29 | 0.26 | −0.16 | 0.54 | −0.06 | 0.81 |

| Number of sessions | −0.25 | 0.29 | −0.19 | 0.41 | −0.32 | −0.17 | −0.03 | 0.91 |

| Sex | −0.28 | 0.23 | −0.01 | 0.96 | −0.33 | 0.16 | −0.35 | 0.13 |

| Psychotic symptoms | −0.17 | 0.46 | −0.4 | 0.08 | 0.1 | 0.67 | −0.08 | 0.73 |

| Depression type | −0.24 | 0.31 | −0.13 | 0.57 | −0.18 | 0.44 | −0.12 | 0.6 |

| Suicidal ideation | −0.53 | 0.016 * | −0.49 | 0.028 * | −0.42 | 0.07 | −0.21 | 0.36 |

| Personality disorder | −0.35 | 0.13 | −0.07 | 0.75 | −0.39 | 0.09 | −0.34 | 0.14 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Stachura, A.; Sawicki, S.; Święcicki, Ł. Improvement in Depressive Symptoms Is Not Associated with the Severity of Autobiographical Amnesia Following Electroconvulsive Therapy—A Preliminary Report from Naturalistic Prospective Observational Study. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 7663. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14217663

Stachura A, Sawicki S, Święcicki Ł. Improvement in Depressive Symptoms Is Not Associated with the Severity of Autobiographical Amnesia Following Electroconvulsive Therapy—A Preliminary Report from Naturalistic Prospective Observational Study. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(21):7663. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14217663

Chicago/Turabian StyleStachura, Albert, Stefan Sawicki, and Łukasz Święcicki. 2025. "Improvement in Depressive Symptoms Is Not Associated with the Severity of Autobiographical Amnesia Following Electroconvulsive Therapy—A Preliminary Report from Naturalistic Prospective Observational Study" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 21: 7663. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14217663

APA StyleStachura, A., Sawicki, S., & Święcicki, Ł. (2025). Improvement in Depressive Symptoms Is Not Associated with the Severity of Autobiographical Amnesia Following Electroconvulsive Therapy—A Preliminary Report from Naturalistic Prospective Observational Study. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(21), 7663. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14217663