Efficiency of 80% vs. 100% Oxygen for Preoxygenation: A Randomized Study on Duration of Apnoea Without Desaturation

Abstract

1. Introduction

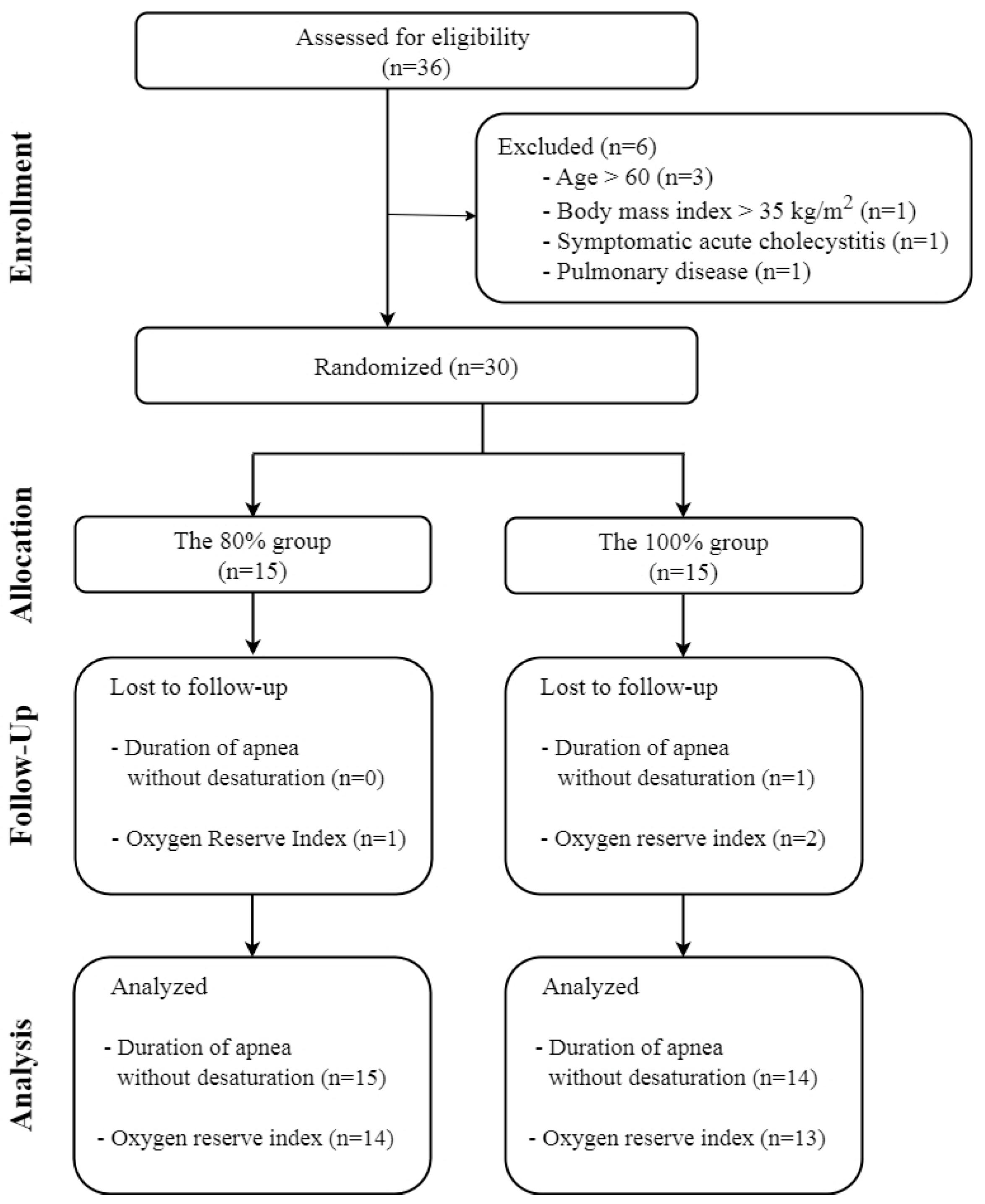

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Population

2.2. Preoxygenation and Anaesthesia Protocol

2.3. Outcome Measures

2.4. Statistical Analysis

2.5. Sample Size Calculation

3. Results

3.1. Efficiency of Preoxygenation

3.2. Efficacy of Preoxygenation

3.3. Oxygen Reserve Index

3.4. SpO2 Recovery Time

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| DAWD | Duration of apnoea without desaturation |

| ORI™ | Oxygen Reserve Index |

| EtO2 | End-tidal oxygen |

| SpO2 | Peripheral oxygen saturation |

| FiO2 | Inspired oxygen fraction |

| IRB | Institutional Review Board |

| CONSORT | Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials |

| ASA | American Society of Anaesthesiologist |

| BMI | Body mass index |

| EtCO2 | End-tidal carbon dioxide |

| IQR | Interquartile range |

| CI | Confidence interval |

References

- Frerk, C.; Mitchell, V.S.; McNarry, A.F.; Mendonca, C.; Bhagrath, R.; Patel, A.; O’Sullivan, E.P.; Woodall, N.M.; Ahmad, I. Difficult Airway Society 2015 Guidelines for Management of Unanticipated Difficult Intubation in Adults. Br. J. Anaesth. 2015, 115, 827–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouroche, G.; Bourgain, J.L. Preoxygenation and General Anesthesia: A Review. Minerva Anestesiol. 2015, 81, 910–920. [Google Scholar]

- Allegranzi, B.; Zayed, B.; Bischoff, P.; Kubilay, N.Z.; de Jonge, S.; de Vries, F.; Gomes, S.M.; Gans, S.; Wallert, E.D.; Wu, X.; et al. New Who Recommendations on Intraoperative and Postoperative Measures for Surgical Site Infection Prevention: An Evidence-Based Global Perspective. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2016, 16, e288–e303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hafner, S.; Beloncle, F.; Koch, A.; Radermacher, P.; Asfar, P. Hyperoxia in Intensive Care, Emergency, and Peri-Operative Medicine: Dr. Jekyll or Mr. Hyde? A 2015 update. Ann. Intensive Care 2015, 5, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pannu, S.R.; Dziadzko, M.A.; Gajic, O. How Much Oxygen? Oxygen Titration Goals During Mechanical Ventilation. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2016, 193, 4–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nimmagadda, U.; Salem, M.R.; Crystal, G.J. Preoxygenation: Physiologic basis, Benefits, and Potential Risks. Anesth. Analg. 2017, 124, 507–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edmark, L.; Kostova-Aherdan, K.; Enlund, M.; Hedenstierna, G. Optimal Oxygen Concentration During Induction of General Anesthesia. Anesthesiology 2003, 98, 28–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akca, O.; Podolsky, A.; Eisenhuber, E.; Panzer, O.; Hetz, H.; Lampl, K.; Lackner, F.X.; Wittmann, K.; Grabenwoeger, F.; Kurz, A.; et al. Comparable Postoperative Pulmonary Atelectasis in Patients Given 30% or 80% Oxygen During and 2 Hours After Colon Resection. Anesthesiology 1999, 91, 991–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scharffenberg, M.; Weiss, T.; Wittenstein, J.; Krenn, K.; Fleming, M.; Biro, P.; De Hert, S.; Hendrickx, J.F.A.; Ionescu, D.; de Abreu, M.G.; et al. Practice of Oxygen Use in Anesthesiology—A Survey of the European Society of Anaesthesiology and Intensive Care. BMC Anesthesiol. 2022, 22, 350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machlin, H.A.; Myles, P.S.; Berry, C.B.; Butler, P.J.; Story, D.A.; Heath, B.J. End-Tidal Oxygen Measurement Compared with Patient Factor Assessment for Determining Preoxygenation Time. Anaesth. Intensive Care 1993, 21, 409–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Driscoll, B.R.; Howard, L.S.; Earis, J.; Mak, V. Bts Guideline for Oxygen Use in Adults in Healthcare and Emergency Settings. Thorax 2017, 72 (Suppl. S1), ii1–ii90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jungbauer, A.; Schumann, M.; Brunkhorst, V.; Borgers, A.; Groeben, H. Expected Difficult Tracheal Intubation: A Prospective Comparison of Direct Laryngoscopy and Video Laryngoscopy in 200 Patients. Br. J. Anaesth. 2009, 102, 546–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kriege, M.; Lang, P.; Lang, C.; Schmidtmann, I.; Kunitz, O.; Roth, M.; Strate, M.; Schmutz, A.; Vits, E.; Balogh, O.; et al. A Comparison of the Mcgrath Videolaryngoscope with Direct Laryngoscopy for Rapid Sequence Intubation in the Operating Theatre: A Multicentre Randomised Controlled Trial. Anaesthesia 2024, 79, 801–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, J.; Park, S.; Lee, M.; Chung, Y.H.; Koo, B.S.; Kim, S.H.; Chae, W.S. Efficacy of Preoxygenation with End-Tidal Oxygen When Using Different Oxygen Concentrations in Patients Undergoing General Surgery: A Single-Center Retrospective Observational Study. Ann. Palliat. Med. 2022, 11, 3636–3647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baraka, A.S.; Taha, S.K.; Aouad, M.T.; El-Khatib, M.F.; Kawkabani, N.I. Preoxygenation: Comparison of Maximal Breathing and Tidal Volume Breathing Techniques. Anesthesiology 1999, 91, 612–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gambee, A.M.; Hertzka, R.E.; Fisher, D.M. Preoxygenation Techniques: Comparison of Three Minutes and Four Breaths. Anesth. Analg. 1987, 66, 468–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatia, P.K.; Bhandari, S.C.; Tulsiani, K.L.; Kumar, Y. End-Tidal Oxygraphy and Safe Duration of Apnoea in Young Adults and Elderly Patients. Anaesthesia 1997, 52, 175–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanoubi, I.; Drolet, P.; Donati, F. Optimizing Preoxygenation in Adults. Can. J. Anaesth. 2009, 56, 449–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nimmagadda, U.; Salem, M.R.; Joseph, N.J.; Lopez, G.; Megally, M.; Lang, D.J.; Wafai, Y. Efficacy of Preoxygenation with Tidal Volume Breathing. Comparison of Breathing Systems. Anesthesiology 2000, 93, 693–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Applegate, R.L., 2nd; Dorotta, I.L.; Wells, B.; Juma, D.; Applegate, P.M. The Relationship Between Oxygen Reserve Index and Arterial Partial Pressure of Oxygen During Surgery. Anesth. Analg. 2016, 123, 626–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vos, J.J.; Willems, C.H.; van Amsterdam, K.; van den Berg, J.P.; Spanjersberg, R.; Struys, M.; Scheeren, T.W.L. Oxygen Reserve Index: Validation of a New Variable. Anesth. Analg. 2019, 129, 409–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshida, K.; Isosu, T.; Noji, Y.; Hasegawa, M.; Iseki, Y.; Oishi, R.; Imaizumi, T.; Sanbe, N.; Obara, S.; Murakawa, M. Usefulness of Oxygen Reserve Index (Ori), a New Parameter of Oxygenation Reserve Potential, for Rapid Sequence Induction of General Anesthesia. J. Clin. Monit. Comput. 2018, 32, 687–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsymbal, E.; Ayala, S.; Singh, A.; Applegate, R.L., 2nd; Fleming, N.W. Study of Early Warning for Desaturation Provided by Oxygen Reserve Index in Obese Patients. J. Clin. Monit. Comput. 2021, 35, 749–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fleming, N.W.; Singh, A.; Lee, L.; Applegate, R.L., 2nd. Oxygen Reserve Index: Utility as an Early Warning for Desaturation in High-Risk Surgical Patients. Anesth. Analg. 2021, 132, 770–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| 80% Group (n = 15) | 100% Group (n = 15) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (y) | 46.1 ± 8.4 | 39.5 ± 9.0 | 0.049 a,* |

| Sex (male: female) | 5:10 (33.3%:66.7%) | 8:7 (53.3%:46.7%) | 0.269 b |

| Weight | 69.1 ± 15.8 | 72.7 ± 16.4 | 0.539 a |

| Height | 162.2 ± 10.8 | 167.5 ± 9.9 | 0.169 a |

| BMI | 26.2 ± 5.2 | 25.6 ± 4.3 | 0.766 a |

| ASA (I:II:III) | 7:7:1 (46.7%:46.7%:6.7%) | 8:6:1 (53.3%:40.0%:6.7%) | 1 c |

| Haemoglobin | 13.9 ± 1.8 | 13.7 ± 1.9 | 0.830 a |

| Haematocrit | 40.1 ± 5.1 | 40.4 ± 5.2 | 0.953 a |

| Smoking (none: current: ex-) | 12:2:1 (80%:13.3%:6.7%) | 9:6:0 (60%:40%:0%) | 0.215 c |

| 80% Group | 100% Group | p-Value | Mean Difference | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Preoxygenation | |||||

| Efficiency (Duration of apnoea without desaturation) | 345 ± 136 | 430 ± 163 | 0.135 a | −86 s | −200 to 28 |

| Efficacy (time to achieve adequate preoxygenation) | 142 ± 53 | 148 ± 58 | 0.774 a | −6 s | −47 to 36 |

| Time taken for adequate preoxygenation (≤180 s:>180 s) | 12:3 (80%:20%) | 10:5 (67%:33%) | 0.682 b | ||

| ORi™ | |||||

| Time from oxygen administration to first ORi™ > 0 | 49 ± 25 | 42 ± 18 | 0.430 a | 6.5 s | −10.3 to 23.4 |

| Time from first ORi™ > 0 to ORi™ dropping to 0 | 420 ± 132 | 533 ± 182 | 0.076 a | −113 s | −238 to 13 |

| Maximum ORi value | 0.61 ± 0.19 | 0.65 ± 0.31 | 0.663 a | −0.04 | −0.44 to 21.69 |

| Additional warning time (from ORi™ dropping to 0 to SpO2 reducing to 97% | 31 [15.5, 45.5] | 46 [33.0, 84.0] | 0.062 c | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jung, J.; Chung, Y.-H.; Koo, B.-S.; Kim, S.-H.; Jin, H.-C.; Chae, W.S. Efficiency of 80% vs. 100% Oxygen for Preoxygenation: A Randomized Study on Duration of Apnoea Without Desaturation. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 7647. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14217647

Jung J, Chung Y-H, Koo B-S, Kim S-H, Jin H-C, Chae WS. Efficiency of 80% vs. 100% Oxygen for Preoxygenation: A Randomized Study on Duration of Apnoea Without Desaturation. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(21):7647. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14217647

Chicago/Turabian StyleJung, Jaewoong, Yang-Hoon Chung, Bon-Sung Koo, Sang-Hyun Kim, Hee-Chul Jin, and Won Seok Chae. 2025. "Efficiency of 80% vs. 100% Oxygen for Preoxygenation: A Randomized Study on Duration of Apnoea Without Desaturation" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 21: 7647. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14217647

APA StyleJung, J., Chung, Y.-H., Koo, B.-S., Kim, S.-H., Jin, H.-C., & Chae, W. S. (2025). Efficiency of 80% vs. 100% Oxygen for Preoxygenation: A Randomized Study on Duration of Apnoea Without Desaturation. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(21), 7647. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14217647