Metoprolol vs. Diltiazem in Patients with Angina and Non-Obstructive Coronary Artery Disease with or Without Evidence of Coronary Microvascular Spasm on Acetylcholine Testing

Abstract

1. Introduction

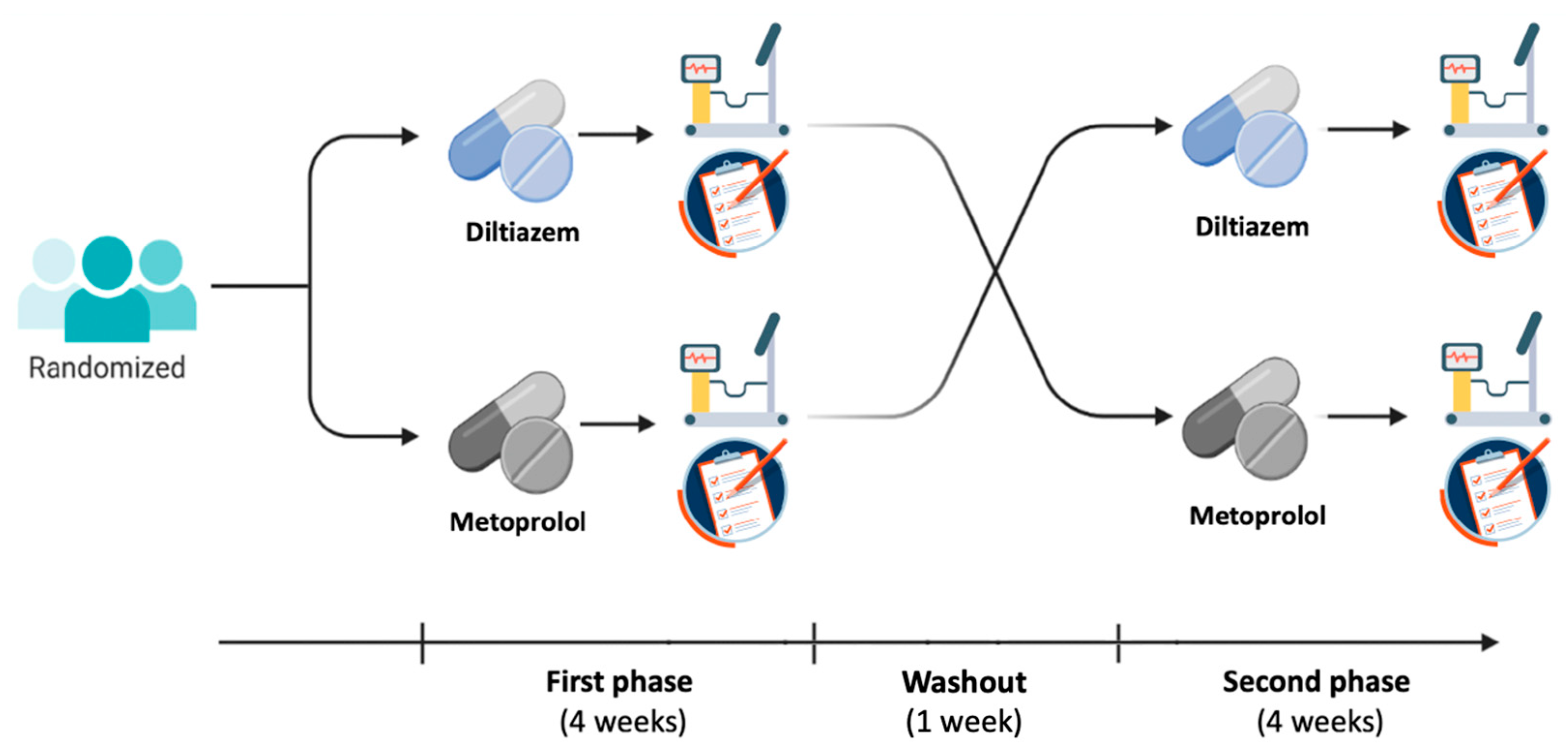

2. Methods

2.1. Patients

2.2. Acetylcholine Test

2.3. Study Design

2.3.1. Seattle Angina Questionnaire

2.3.2. Exercise Stress Test

2.4. Statistics

3. Results

3.1. Angina Status

3.2. Exercise Stress Test

4. Discussion

Limitations of the Study

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| Ach | Acetylcholine |

| ANOCA | Angina with non-obstructive coronary artery disease |

| BBs | Betablockers |

| CAS | Coronary artery spasm |

| CCBs | Calcium-channel blockers |

| CFR | Coronary flow reserve |

| CFTs | Coronary function tests |

| CMVS | Coronary microvascular spasm |

| ECG-EST | ECG–exercise stress test |

| SAQ | Seattle Angina Questionnaire |

| STD | ST-segment depression |

References

- Patel, M.R.; Peterson, E.D.; Dai, D.; Brennan, J.M.; Redberg, R.F.; Anderson, H.V.; Brindis, R.G.; Douglas, P.S. Low diagnostic yield of elective coronary angiography. N. Engl. J. Med. 2010, 362, 886–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gehrie, E.R.; Reynolds, H.R.; Chen, A.Y.; Neelon, B.H.; Roe, M.T.; Gibler, W.B.; Ohman, E.M.; Newby, L.K.; Peterson, E.D.; Hochman, J.S. Characterization and outcomes of women and men with non-ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction and nonobstructive coronary artery disease: Results from the Can Rapid Risk Stratification of Unstable Angina Patients Suppress Adverse Outcomes with Early Implementation of the ACC/AHA Guidelines (CRUSADE) quality improvement initiative. Am. Heart J. 2009, 158, 688–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanza, G.A.; Morrone, D.; Pizzi, C.; Tritto, I.; Bergamaschi, L.; De Vita, A.; Villano, A.; Crea, F. Diagnostic approach for coronary microvascular dysfunction in patients with chest pain and no obstructive coronary artery disease. Trends Cardiovasc. Med. 2021, 32, 448–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanza, G.A.; Crea, F. Primary coronary microvascular dysfunction: Clinical presentation, pathophysiology, and management. Circulation 2010, 121, 2317–2325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunadian, V.; Chieffo, A.; Camici, P.G.; Berry, C.; Escaned, J.; Maas, A.H.E.M.; Prescott, E.; Karam, N.; Appelman, Y.; Fraccaro, C.; et al. An EAPCI Expert Consensus Document on Ischaemia with Non-Obstructive Coronary Arteries in Collaboration with European Society of Cardiology Working Group on Coronary Pathophysiology & Microcirculation Endorsed by Coronary Vasomotor Disorders International Study Group. Eur. Heart J. 2020, 41, 3504–3520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perera, D.; Berry, C.; Hoole, S.P.; Sinha, A.; Rahman, H.; Morris, P.D.; Kharbanda, R.K.; Petraco, R.; Channon, K. UK Coronary Microvascular Dysfunction Working Group. Invasive coronary physiology in patients with angina and non-obstructive coronary artery disease: A consensus document from the coronary microvascular dysfunction workstream of the British Heart Foundation/National Institute for Health Research Partnership. Heart 2022, 109, 88–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ford, T.J.; Stanley, B.; Good, R.; Rocchiccioli, P.; McEntegart, M.; Watkins, S.; Eteiba, H.; Shaukat, A.; Lindsay, M.; Robertson, K.; et al. Stratified Medical Therapy Using Invasive Coronary Function Testing in Angina: The CorMicA Trial. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2018, 72, 2841–2855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ford, T.J.; Stanley, B.; Sidik, N.; Good, R.; Rocchiccioli, P.; McEntegart, M.; Watkins, S.; Eteiba, H.; Shaukat, A.; Lindsay, M.; et al. 1-Year Outcomes of Angina Management Guided by Invasive Coronary Function Testing (CorMicA). JACC Cardiovasc. Interv. 2020, 13, 33–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sidik, N.P.; Stanley, B.; Sykes, R.; Morrow, A.J.; Bradley, C.P.; McDermott, M.; Ford, T.J.; Roditi, G.; Hargreaves, A.; Stobo, D.; et al. Invasive Endotyping in Patients With Angina and No Obstructive Coronary Artery Disease: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Circulation 2024, 149, 7–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jansen, T.P.J.; Konst, R.E.; de Vos, A.; Paradies, V.; Teerenstra, S.; Oord, S.C.v.D.; Dimitriu-Leen, A.; Maas, A.H.; Smits, P.C.; Damman, P.; et al. Efficacy of Diltiazem to Improve Coronary Vasomotor Dysfunction in ANOCA: The EDIT-CMD Randomized Clinical Trial. JACC Cardiovasc. Imaging 2022, 15, 1473–1484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Montone, R.A.; Niccoli, G.; Fracassi, F.; Russo, M.; Gurgoglione, F.; Cammà, G.; Lanza, G.A.; Crea, F. Patients with acute myocardial infarction and non-obstructive coronary arteries: Safety and prognostic relevance of invasive coronary provocative tests. Eur. Heart J. 2018, 39, 91–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ong, P.; Athanasiadis, A.; Borgulya, G.; Vokshi, I.; Bastiaenen, R.; Kubik, S.; Hill, S.; Schäufele, T.; Mahrholdt, H.; Kaski, J.C.; et al. Clinical usefulness, angiographic characteristics, and safety evaluation of intracoronary acetylcholine provocation testing among 921 consecutive white patients with unobstructed coronary arteries. Circulation 2014, 129, 1723–1730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spertus, J.A.; Winder, J.A.; Dewhurst, T.A.; Deyo, R.A.; Prodzinski, J.; McDonnell, M.; Fihn, S.D. Development and evaluation of the Seattle Angina Questionnaire: A new functional status measure for coronary artery disease. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 1995, 25, 333–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, P.S.; Jones, P.G.; Arnold, S.A.; Spertus, J.A. Development and validation of a short version of the Seattle angina questionnaire. Circ. Cardiovasc. Qual. Outcomes 2014, 7, 640–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bairey Merz, C.N.; Handberg, E.M.; Shufelt, C.L.; Mehta, P.K.; Minissian, M.B.; Wei, J.; Thomson, L.E.; Berman, D.S.; Shaw, L.J.; Petersen, J.W.; et al. A randomized, placebo-controlled trial of late Na current inhibition (ranolazine) in coronary microvascular dysfunction (CMD): Impact on angina and myocardial perfusion reserve. Eur. Heart J. 2016, 37, 1504–1513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villano, A.; Di Franco, A.; Nerla, R.; Sestito, A.; Tarzia, P.; Lamendola, P.; Di Monaco, A.; Sarullo, F.M.; Lanza, G.A.; Crea, F. Effects of ivabradine and ranolazine in patients with microvascular angina pectoris. Am. J. Cardiol. 2013, 112, 8–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanza, G.A.; Colonna, G.; Pasceri, V.; Maseri, A. Atenolol versus amlodipine versus isosorbide5-mononitrate on anginal symptoms in syndrome X. Am. J. Cardiol. 1999, 84, 854–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romeo, F.; Gaspardone, A.; Ciavolella, M.; Gioffrè, P.; Reale, A. Verapamil versus acebutolol for syndrome X. Am. J. Cardiol. 1988, 62, 312–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferrini, D.; Bugiardini, R.; Galvani, M.; Gioffrè, P.; Reale, A. Opposing effects of propranolol and diltiazem on the angina threshold during an exercise test in patients with syndrome X. G. Ital. Cardiol. 1986, 16, 224–231. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bugiardini, R.; Borghi, A.; Biagetti, L.; Puddu, P. Comparison of verapamil versus propranolol therapy in syndrome X. Am. J. Cardiol. 1989, 63, 286–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crea, F.; Lanza, G.A. Treatment of microvascular angina: The need for precision medicine. Eur. Heart J. 2016, 37, 1514–1516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ong, P.; Camici, P.G.; Beltrame, J.F.; Crea, F.; Shimokawa, H.; Sechtem, U.; Kaski, J.C.; Merz, C.N.B.; Coronary Vasomotion Disorders International Study Group (COVADIS). International standardization of diagnostic criteria for microvascular angina. Int. J. Cardiol. 2018, 250, 16–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Masumoto, A.; Mohri, M.; Takeshita, A. Three-year follow-up of the Japanese patients with microvascular angina attributable to coronary microvascular spasm. Int. J. Cardiol. 2001, 81, 151–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohba, K.; Sugiyama, S.; Sumida, H.; Nozaki, T.; Matsubara, J.; Matsuzawa, Y.; Konishi, M.; Akiyama, E.; Kurokawa, H.; Maeda, H.; et al. Microvascular coronary artery spasm presents distinctive clinical features with endothelial dysfunction as nonobstructive coronary artery disease. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2012, 1, e002485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Setiz, A.; Feenstra, R.; Konst, R.E.; Pereyra, V.M.; Beck, S.; Beijk, M.A.M.; van de Hoef, T.P.; van Royen, N.; Bekeredjian, R.; Sechtem, U.; et al. Acetylcholine Rechallange: A First Step Toward Tailored Treatment in Patients With Coronary Artery Spasm. JACC Cardiovasc. Interv. 2022, 15, 65–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marino, A.G.; Gentile, G.; Lenci, L.; De Benedetto, F.; Tremamunno, S.; Cambise, N.; Belmusto, A.; Di Renzo, A.; Tinti, L.; De Vita, A.; et al. Comparison of Baseline and Post-Nitrate Exercise Testing in Patients with Angina but Non-Obstructed Coronary Arteries with Different Acetylcholine Test Results. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 2181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanza, G.A.; Shimokawa, H. Management of Coronary Artery Spasm. Eur. Cardiol. 2023, 18, e38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robertson, R.M.; Wood, A.J.; Vaughn, W.K.; Robertson, D. Exacerbation of vasotonic angina pectoris by propranolol. Circulation 1982, 65, 281–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanza, G.A.; Parrinello, R.; Figliozzi, S. Management of microvascular angina pectoris. Am. J. Cardiovasc. Drugs 2014, 14, 31–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crea, F.; Camici, P.G.; Bairey Merz, C.N. Coronary microvascular dysfunction: An update. Eur. Heart J. 2014, 35, 1101–1111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ong, P.; Athanasiadis, A.; Borgulya, G.; Mahrholdt, H.; Kaski, J.C.; Sechtem, U. High prevalence of a pathological response to acetylcholine testing in patients with stable angina pectoris and unobstructed coronary arteries. The ACOVA Study (Abnormal COronary VAsomotion in patients with stable angina and unobstructed coronary arteries). J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2012, 59, 655–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fragasso, G.; Chierchia, S.L.; Pizzetti, G.; Rossetti, E.; Carlino, M.; Gerosa, S.; Carandente, O.; Fedele, A.; Cattaneo, N. Impaired left ventricular filling dynamics in patients with angina and angiographically normal coronary arteries: Effect of beta-adrenergic blockade. Heart 1997, 77, 32–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leonardo, F.; Fragasso, G.; Rossetti, E.; Dabrowski, P.; Pagnotta, P.; Rosano, G.M.; Chierchia, S.L. Comparison of trimetazidine with atenolol in patients with syndrome X: Effects on diastolic function and exercise tolerance. Cardiologia 1999, 44, 1065–1069. [Google Scholar]

- Cannon, R.O.; Watson, R.M.; Rosing, D.R.; Epstein, S.E. Efficacy of calcium channel blocker therapy for angina pectoris resulting from small-vessel coronary artery disease and abnormal vasodilator reserve. Am. J. Cardiol. 1985, 56, 242–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozcelik, F.; Altun, A.; Ozbay, G. Angianginal and anti-ischemic effect of nisoldipine and ramipril in patients with syndrome X. Clin. Cardiol. 1999, 22, 361–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Gu, Y.; Liu, T.; Hou, L.; Cheng, Z.; Hu, L.; Gao, B. A randomized, single-center double-blinded trial on the effects of diltiazem sustained-release capsules in patients with coronary slow-flow phenomenon at 6-month follow-up. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e38851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boerhout, C.K.M.; Namba, H.F.; Liu, T.; Beijk, M.A.M.; Damman, P.; Meuwissen, M.; Ong, P.; Sechtem, U.; Appelman, Y.; Berry, C.; et al. Coronary function testing vs angiography alone to guide treatment of angina with non-obstructive coronary arteries: The ILIAS ANOCA trial. Eur. Heart J. 2025, ehaf580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Study Design | Population | No. pts | Drugs Tested | Outcome | Results | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lanza [11] | Crossover, randomized, double-blind |

| 10 | Atenolol vs. amlodipine vs. ISMN 5-mononitrate | Angina episodes | Only atenolol significantly reduced angina episodes |

| Romeo [12] | Crossover, double-blind, randomized |

| 30 | Acebutolol vs. verapamil | ECG-EST | Verapamil improved ECG-EST in the whole population; acebutolol improved ECG-EST in patients with enhanced sympathetic activity only |

| Ferrini [13] | Crossover, randomized, single-blind |

| 13 | Propanolol vs. diltiazem vs. placebo | ECG-EST | Diltiazem, but not propranolol, improved ECG-EST results |

| Leonardo [14] | Crossover, randomized, double-blind |

| 16 | Atenolol vs. trimetazidine vs. placebo | Angina episodes, ECG-EST, echocardiograhy | Atenolol, but not trimetazidine, reduced angina episodes, ECG-EST abnormalities, and improved diastolic function |

| Cannon [15] | Crossover, double-blind, randomized |

| 26 | Verapamil vs. nifedipine vs. placebo | Angina episodes, nitrate use, ECG-EST | CCBC reduced angina episodes and nitrate consumption and improved ECG-EST results. |

| Ozcelik [16] | Crossover, non-randomized open-label, |

| 18 | Nisoldipine vs. ramipril | Angina episodes, nitrate use, ECG-EST | Nisoldipine and ramipril reduced angina episodes and nitrate consumption and improved ECG-EST results. |

| Li [17] | Randomized, double-blind trial |

| 80 | Diltiazem vs. placebo | Angina episodes, ECG-EST, CBF | Diltiazem reduced angina episodes and improved ECG-EST results, and coronary blood flow |

| CMVS Group (n = 16) | NEG Group (n = 15) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Angina | 16 (100%) | 5 (33%) | <0.001 |

| Ischemic ECG changes | 16 (100%) | 1 (7%) | <0.001 |

| Mild focal vasoconstriction (<75%) | 3 (19%) | 1 (7%) | 0.32 |

| Mild diffuse vasoconstriction (<75%) | 2 (13%) | 3 (20%) | 0.57 |

| Ach maximal dose | 55 ± 23 | 100 ± 0 | <0.001 |

| CMVS Group (n = 16) | NEG Group (n = 15) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 56 ± 10 | 62 ± 13 | 0.15 |

| Sex (M/F) | 3/13 | 5/10 | 0.43 |

| Cardiovascular risk factors | |||

| Family history of CVD | 4 (25%) | 6 (40%) | 0.46 |

| Hypertension | 6 (38%) | 9 (60%) | 0.29 |

| Active smoking | 5 (31%) | 3 (20%) | 0.69 |

| Hypercholesterolemia | 6 (38%) | 8 (53%) | 0.48 |

| Diabetes | 3 (19%) | 3 (20%) | 0.93 |

| Clinical presentation | |||

| Stable angina | 5 (31%) | 8 (53%) | 0.78 |

| Unstable angina | 11 (69%) | 7 (47%) | 0.29 |

| Other cardiovascular drugs | |||

| ACE-inhibitors/ARBs | 7 (44%) | 7 (47%) | 0.87 |

| Diuretics | 1 (6%) | 2 (13%) | 0.60 |

| Statins | 7 (44%) | 4 (27%) | 0.46 |

| Aspirin | 10 (63%) | 8 (53%) | 0.72 |

| CMVS Group (n = 14) | NEG Group (n = 14) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Metoprolol | Diltiazem | p | Metoprolol | Diltiazem | p | |

| Physical limitation | 70.7 ± 31 | 67.9 ± 36 | 0.79 | 77.9 ± 19 | 80.5 ± 17 | 0.58 |

| Angina stability | 59.4 ± 37 | 61.9 ± 35 | 0.74 | 53.6 ± 35 | 71.1 ± 32 | 0.14 |

| Angina frequency | 67.5 ± 30 | 70.4 ± 27 | 0.47 | 77.9 ± 17 | 80.7 ± 15 | 0.45 |

| Treatment satisfaction | 71.9 ± 22 | 73.6 ± 26 | 0.68 | 72.8 ± 21 | 77.6 ± 19 | 0.26 |

| Quality of life | 51.1 ± 27 | 59.7 ± 28 | 0.08 | 57.1 ± 24 | 61.5 ± 28 | 0.47 |

| CMVS Group (n = 14) | NEG Group (n = 14) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Metoprolol | |||

| Hypotension | 0 (0%) | 1 (7%) | 0.31 |

| Fatigue | 3 (21%) | 2 (14%) | 0.62 |

| Dizziness | 1 (7%) | 1 (7%) | - |

| Diltiazem | |||

| Hypotension | 2 (14%) | 1 (7%) | 0.34 |

| Headache | 2 (14%) | 3 (21%) | 0.62 |

| Constipation | 1 (7%) | 0 (0%) | 0.31 |

| CMVS Group (n = 10) | NEG Group (n = 12) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Metoprolol | Diltiazem | p | Metoprolol | Diltiazem | p | |

| Rest | ||||||

| HR (bpm) | 70 ± 21 | 73 ± 9 | 0.57 | 70 ± 10 | 74 ± 10 | 0.19 |

| Systolic BP (mmHg) | 129 ± 18 | 121 ± 16 | 0.57 | 127 ± 14 | 131 ± 15 | 0.42 |

| Diastolic BP (mmHg) | 75 ± 9 | 73 ± 8 | 0.24 | 78 ± 6 | 78 ± 9 | 0.73 |

| 1 mm STD | ||||||

| HR (bpm) | 119 ± 19 | 125 ± 17 | 0.04 | 122 ± 24 | 130 ± 24 | 0.12 |

| Systolic BP (mmHg) | 154 ± 17 | 146 ± 13 | 0.07 | 144 ± 17 | 155 ± 14 | 0.04 |

| Diastolic BP (mmHg) | 81 ± 8 | 75 ± 7 | 0.06 | 83 ± 11 | 86 ± 9 | 0.27 |

| Time to 1 mm (s) | 424 ± 192 | 399 ± 173 | 0.55 | 401 ± 149 | 420 ± 172 | 0.53 |

| Peak exercise | ||||||

| HR (bpm) | 129 ± 15 | 137 ± 13 | 0.07 | 132 ± 21 | 139 ± 21 | 0.07 |

| Systolic BP (mmHg) | 168 ± 13 | 155 ± 18 | <0.01 | 158 ± 25 | 161 ± 19 | 0.62 |

| Diastolic BP (mmHg) | 85 ± 10 | 79 ± 6 | 0.07 | 87 ± 10 | 87 ± 9 | 0.90 |

| EST duration (s) | 508 ± 137 | 491 ± 118 | 0.44 | 468 ± 96 | 514 ± 99 | 0.01 |

| Positive EST | 7 (70%) | 8 (80%) | 1.0 | 6 (50%) | 7 (58%) | 1.0 |

| Angor | 1 (10%) | 1 (10%) | 1.0 | 6 (50%) | 6 (50%) | 1.0 |

| Maximal STD (mm) | 1.1 ± 0.8 | 1.1 ± 0.7 | 0.78 | 1.0 ± 1.2 | 1.0 ± 1.1 | 0.75 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Marino, A.G.; Cambise, N.; De Benedetto, F.; Lenci, L.; Pontecorvo, S.; Di Perna, F.; Buonamassa, G.; Belmusto, A.; Tremamunno, S.; De Vita, A.; et al. Metoprolol vs. Diltiazem in Patients with Angina and Non-Obstructive Coronary Artery Disease with or Without Evidence of Coronary Microvascular Spasm on Acetylcholine Testing. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 7635. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14217635

Marino AG, Cambise N, De Benedetto F, Lenci L, Pontecorvo S, Di Perna F, Buonamassa G, Belmusto A, Tremamunno S, De Vita A, et al. Metoprolol vs. Diltiazem in Patients with Angina and Non-Obstructive Coronary Artery Disease with or Without Evidence of Coronary Microvascular Spasm on Acetylcholine Testing. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(21):7635. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14217635

Chicago/Turabian StyleMarino, Angelo Giuseppe, Nello Cambise, Fabio De Benedetto, Ludovica Lenci, Sara Pontecorvo, Federico Di Perna, Giacomo Buonamassa, Antonietta Belmusto, Saverio Tremamunno, Antonio De Vita, and et al. 2025. "Metoprolol vs. Diltiazem in Patients with Angina and Non-Obstructive Coronary Artery Disease with or Without Evidence of Coronary Microvascular Spasm on Acetylcholine Testing" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 21: 7635. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14217635

APA StyleMarino, A. G., Cambise, N., De Benedetto, F., Lenci, L., Pontecorvo, S., Di Perna, F., Buonamassa, G., Belmusto, A., Tremamunno, S., De Vita, A., Capasso, R., Montone, R. A., & Lanza, G. A. (2025). Metoprolol vs. Diltiazem in Patients with Angina and Non-Obstructive Coronary Artery Disease with or Without Evidence of Coronary Microvascular Spasm on Acetylcholine Testing. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(21), 7635. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14217635