Multi-Collaborator Engagement to Identify Research Priorities for Early Intervention in Cerebral Palsy

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Preconference Survey

2.2. Conference Focus Groups

2.3. Post-Conference Validation Survey

2.4. Data Analysis

2.4.1. Pre-Conference Survey

2.4.2. Focus Groups

2.4.3. Data Integration and Validation

3. Results

3.1. Pre-Conference Survey (n = 36)

3.2. Conference Focus Groups (n = 97)

3.3. Quantitative and Qualitative Data Synthesis and Actionable Items

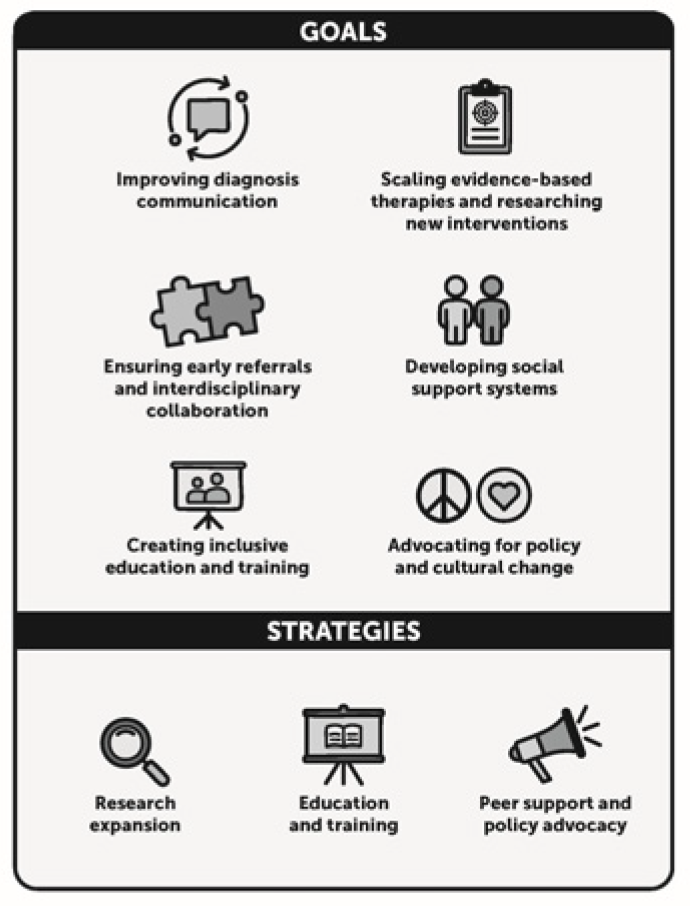

- Improving diagnosis communication: Emphasizing empathy and clarity when informing families about a CP diagnosis.

- Ensuring early referrals and interdisciplinary collaboration: Promoting proactive care and comprehensive networks.

- Creating inclusive education and training: Enhancing the skills and empathy of care providers while fostering self-advocacy among families.

- Scaling evidence-based therapies and researching new interventions: Expanding accessibility in proven therapeutic interventions and researching new, innovative interventions.

- Developing social support systems: Developing parent navigators, peer support groups, and advocacy networks.

- Advocating for policy and cultural change: Promoting insurance reforms, inclusive communities, and media-driven awareness campaigns.

3.4. Conference Follow-Up Survey (n = 16)

3.5. Development of a Framework to Address Identified Priorities

4. Discussion

Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CIMT | constraint-induced movement therapy |

| CP | cerebral palsy |

| DFW | Dallas–Fort Worth |

| ECI | early childhood intervention |

| G-button | gastrostomy button |

| HCS | Home and Community-based Services |

| IDD | intellectual and developmental disabilities |

| OT | occupational therapy |

| PT | physical therapy/physical therapist |

References

- Rosenbaum, P.; Paneth, N.; Leviton, A.; Goldstein, M.; Bax, M.; Damiano, D.; Dan, B.; Jacobsson, B. A report: The definition and classification of cerebral palsy April 2006. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. Suppl. 2007, 109 (Suppl. S109), 8–14. [Google Scholar]

- Accardo, P.J.; Hoon, A.H. The challenge of cerebral palsy classification: The ELGAN study. J. Pediatr. 2008, 153, 451–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novak, I.; Morgan, C.; Adde, L.; Blackman, J.; Boyd, R.N.; Brunstrom-Hernandez, J.; Cioni, G.; Damiano, D.; Darrah, J.; Eliasson, A.-C.; et al. Early, accurate diagnosis and early intervention in cerebral palsy: Advances in diagnosis and treatment. JAMA Pediatr. 2017, 171, 897–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moharir, M.; Kulkarni, C. Update in Infant Development. In Update in Pediatrics; Springer: Cham Switzerland, 2024; pp. 183–251. [Google Scholar]

- Center on the Developing Child at Harvard University. The Foundations of Lifelong Health Are Built in Early Childhood. 2010. Available online: https://developingchild.harvard.edu/resources/report/the-foundations-of-lifelong-health-are-built-in-early-childhood/ (accessed on 14 April 2025).

- Hidalgo-Robles, Á.; Merino-Andrés, J.; Cisse, M.R.S.; Pacheco-Molero, M.; León-Estrada, I.; Gutiérrez-Ortega, M. The pathway is clear but the road remains unpaved: A scoping review of implementation of tools for early detection of cerebral palsy. Children 2025, 12, 941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hornby, B.; Paleg, G.S.; Williams, S.A.; Hidalgo-Robles, Á.; Livingstone, R.W.; Montufar Wright, P.E.; Taylor, A.; Shrader, M.W. Identifying opportunities for early detection of cerebral palsy. Children 2024, 11, 515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, S.A.; Mackey, A.; Sorhage, A.; Battin, M.; Wilson, N.; Spittle, A.; Stott, N.S. Clinical practice of health professionals working in early detection for infants with or at risk of cerebral palsy across New Zealand. J. Paediatr. Child Health 2021, 57, 541–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Merino-Andrés, J.; Hidalgo-Robles, Á.; Pérez-Nombela, S.; Williams, S.A.; Paleg, G.; Fernández-Rego, F.J. Tool use for early detection of cerebral palsy: A survey of Spanish pediatric physical therapists. Pediatr. Phys. Ther. 2022, 34, 202–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza, R.F.; Leite, H.R.; Lucena, R.; Carvalho, A. Early detection and intervention for children with high risk of cerebral palsy: A survey of physical therapists and occupational therapists in Brazil. Phys. Occup. Ther. Pediatr. 2024, 44, 829–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damiano, D.L.; Longo, E. Early intervention evidence for infants with or at risk for cerebral palsy: An overview of systematic reviews. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 2021, 63, 771–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurvitz, E.A.; Gross, P.H.; Gannotti, M.E.; Bailes, A.F.; Horn, S.D. Registry-based research in cerebral palsy: The Cerebral Palsy Research Network. Phys. Med. Rehabil. Clin. N. Am. 2019, 31, 185–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne, R.; Duncan, A.; Pickar, T.; Burkhardt, S.; Boyd, R.N.; Neel, M.L.; Maitre, N.L. Comparing parent and provider priorities in discussions of early detection and intervention for infants with and at risk of cerebral palsy. Child Care Health Dev. 2019, 45, 799–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gmmash, A.S.; Effgen, S.K. Early intervention therapy services for infants with or at risk for cerebral palsy. Pediatr. Phys. Ther. 2019, 31, 242–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gross, P.H.; Bailes, A.F.; Horn, S.D.; Hurvitz, E.A.; Kean, J.; Shusterman, M.; For the Cerebral Palsy Research Network. Setting a patient-centered research agenda for cerebral palsy: A participatory action research initiative. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 2018, 60, 1278–1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne, R.; Noritz, G.; Maitre, N.L.; NCH Early Developmental Group. Implementation of early diagnosis and intervention guidelines for cerebral palsy in a high-risk infant follow-up clinic. Pediatr. Neurol. 2017, 76, 66–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke; Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. 2017 NINDS/NICHD Strategic Plan for Cerebral Palsy Research. 2017. Available online: https://www.ninds.nih.gov/about-ninds/what-we-do/strategic-plans-evaluations/strategic-plans/cerebral-palsy-research/2017-nindsnichd-strategic-plan-cerebral-palsy-research (accessed on 14 April 2025).

- Lungu, C.; Hirtz, D.; Damiano, D.; Gross, P.; Mink, J.W. Report of a workshop on research gaps in the treatment of cerebral palsy. Neurology 2016, 87, 1293–1298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morgan, C.; Darrah, J.; Gordon, A.M.; Harbourne, R.; Spittle, A.; Johnson, R.; Fetters, L. Effectiveness of motor interventions in infants with cerebral palsy: A systematic review. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 2016, 58, 900–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hadders-Algra, M. Early diagnosis and early intervention in cerebral palsy. Front. Neurol. 2014, 5, 185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McIntyre, S.; Morgan, C.; Walker, K.; Novak, I. Cerebral palsy—Don’t delay. Dev. Disabil. Res. Rev. 2011, 17, 114–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McIntyre, S.; Novak, I.; Cusick, A. Consensus research priorities for cerebral palsy: A Delphi survey of consumers, researchers, and clinicians. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 2010, 52, 270–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Novak, I.; Morgan, C.; Fahey, M.; Finch-Edmondson, M.; Galea, C.; Hines, A.; Langdon, K.; Mc Namara, M.; Paton, M.C.; Popat, H.; et al. State of the evidence traffic lights 2019: Systematic review of interventions for preventing and treating children with cerebral palsy. Curr. Neurol. Neurosci. Rep. 2020, 20, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J.W.; Creswell, J.D. Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Neergaard, M.A.; Olesen, F.; Andersen, R.S.; Sondergaard, J. Qualitative description—The poor cousin of health research? BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2009, 9, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krefting, L. Rigor in qualitative research: The assessment of trustworthiness. Am. J. Occup. Ther. 1991, 45, 214–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novak, I.; Morgan, C.; McNamara, L.; Te Velde, A. Best practice guidelines for communicating to parents the diagnosis of disability. Early Hum. Dev. 2019, 139, 104841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilson, J.L.; Kim, Y.-M.; O’Malley, J.A.; Gelineau-Morel, R.; Gilbert, L.; Bain, J.M.; Aravamuthan, B.R. Cerebral palsy in child neurology and neurodevelopmental disabilities training: An unmet need. J. Child Neurol. 2022, 37, 194–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nieto, L.A.; Cantero, M.J.P.; Nogueira, D.H.; Martínez, J.B. Knowledge and opinion on integrated care for children with cerebral palsy in Primary Care. Rev. Pediatr. Aten. Primaria 2022, 24, 261–271. [Google Scholar]

- Mouilly, M.; Faiz, N.; Ahami, A.O.T. Physiotherapy of cerebral palsy: Skills, performance and prospects in the Rabat-Salé-Kénitra region northwest of Morocco. Motricite Cerebrale 2017, 38, 50–58. [Google Scholar]

- Saleh, M.; Korner-Bitensky, N.; Snider, L.; Malouin, F.; Mazer, B.; Kennedy, E.; Roy, M.-A. Actual vs. best practices for young children with cerebral palsy: A survey of paediatric occupational therapists and physical therapists in Quebec, Canada. Dev. Neurorehabil. 2008, 11, 60–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Case-Smith, J.; DeLuca, S.C.; Stevenson, R.; Ramey, S.L. Multicenter randomized controlled trial of pediatric constraint-induced movement therapy: 6-month follow-up. Am. J. Occup. Ther. 2012, 66, 15–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerebral Palsy Foundation. 2025. Available online: https://www.yourcpf.org (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- Cerebral Palsy Research Network. 2025. Available online: https://cprn.org (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- Cerebral Palsy Alliance Research Foundation. 2025. Available online: https://cparf.org (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- Hettiarachchi, S.; Kitnasamy, G.; Mahendran, R.; Nizar, F.S.; Bandara, C.; Gowritharan, P. Efficacy of a low-cost multidisciplinary team-led experiential workshop for public health midwives on dysphagia management for children with cerebral palsy. Disabil. CBR Incl. Dev. 2018, 29, 67–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanson, J.H.; Majnemer, A.; Pietrangelo, F.; Dickson, L.; Shikako, K.; Dahan-Oliel, N.; Steven, E.; Iliopoulos, G.; Ogourtsova, T. Evidence-based early rehabilitation for children with cerebral palsy: Co-development of a multifaceted knowledge translation strategy for rehabilitation professionals. Front. Rehabil. Sci. 2024, 5, 1413240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maitre, N.L.; Chorna, O.; Romeo, D.M.; Guzzetta, A. Implementation of the Hammersmith Infant Neurological Examination in a high-risk infant follow-up program. Pediatr. Neurol. 2016, 65, 31–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sutter, E.N.; Legare, J.M.; Villegas, M.A.; Collins, K.M.; Eickhoff, J.; Gillick, B.T. Evidence-based infant assessment for cerebral palsy: Diagnosis timelines and intervention access in a newborn follow-up setting. J. Child Neurol. 2024, 39, 461–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butera, C.D.; Yeh, A.; Biniwale, M.; Bloch, E.; Craddock, D.; Doyle, M.; Iyer, S.N.; Kretch, K.S.; Liu, N.; Mirzaian, C.B.; et al. Development and initial outcomes of the interdisciplinary ‘Early Identification and Intervention for Infants Network’ (Ei3) in Los Angeles. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 7442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidson, S.-A.; Ward, R.; Elliott, C.; Harris, C.; Bear, N.; Thornton, A.; Salt, A.; Valentine, J. From guidelines to practice: A retrospective clinical cohort study investigating implementation of the early detection guidelines for cerebral palsy in a state-wide early intervention service. BMJ Open 2022, 12, e063296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulqueeney, A.; Battin, M.; McKillop, A.; Stott, N.S.; Allermo-Fletcher, A.; Williams, S.A. A prospective assessment of readiness to implement an early detection of cerebral palsy pathway in a neonatal intensive care setting using the PARIHS framework. Implement. Sci. Commun. 2024, 5, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hidalgo-Robles, Á.; Merino-Andrés, J.; Rodríguez-Fernández, Á.L.; Gutiérrez-Ortega, M.; León-Estrada, I.; Ródenas-Martínez, M. Reliability, knowledge translation, and implementability of the Spanish version of the Hammersmith Infant Neurological Examination. Healthcare 2024, 12, 380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sakzewski, L.; Ziviani, J.; Boyd, R.N. Delivering evidence-based upper limb rehabilitation for children with cerebral palsy: Barriers and enablers identified by three pediatric teams. Phys. Occup. Ther. Pediatr. 2014, 34, 368–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vurrabindi, D.; Hilderley, A.J.; Kirton, A.; Andersen, J.; Cassidy, C.; Kingsnorth, S.; Munce, S.; Agnew, B.; Cambridge, L.; Herrero, M.; et al. Facilitators and barriers to implementation of early intensive manual therapies for young children with cerebral palsy across Canada. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2025, 25, 503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanson, J.; Sasitharan, A.; Ogourtsova, T.; Majnemer, A. Knowledge translation strategies used to promote evidence-based interventions for children with cerebral palsy: A scoping review. Disabil. Rehabil. 2025, 47, 827–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tommy, R.; Badrinarayanan, M.K.; Ravindranathan, R.; George, S.R. Assessing current cerebral palsy therapy and identifying needs for improvement. J. Intellect. Disabil. Diagn. Treat. 2024, 12, 252–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berdina, O.N.; Bairova, T.A.; Rychkova, L.V.; Sheptunov, S.A. The pediatric robotic-assisted rehabilitation complex for children and adolescents with cerebral palsy: Background and product design. In Proceedings of the 2017 International Conference “Quality Management, Transport and Information Security, Information Technologies” (IT&QM&IS), St. Petersburg, Russia, 24–30 September 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Bayón, C.; Raya, R.; Lerma Lara, S.; Ramirez, O.; Serrano, J.I.; Rocon, E. Robotic therapies for children with cerebral palsy: A systematic review. Transl. Biomed. 2016, 7, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llamas-Ramos, R.; Sánchez-González, J.L.; Llamas-Ramos, I. Robotic systems for the physiotherapy treatment of children with cerebral palsy: A systematic review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 5116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herbert, D.L.; Barnett, A.G.; White, R.; Novak, I.; Badawi, N. Funding for cerebral palsy research in Australia, 2000–2015: An observational study. BMJ Open 2016, 6, e012924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keep, S.G.; Omichinski, D.; Peterson, M.D. Recent trends in National Institutes of Health funding for cerebral palsy lifespan research. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 2025, 67, 1226–1231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moriwaki, M.; Yuasa, H.; Kakehashi, M.; Suzuki, H.; Kobayashi, Y. Impact of social support for mothers as caregivers of cerebral palsy children in Japan. J. Pediatr. Nurs. 2022, 63, e64–e71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prest, K.R.; Borek, A.J.; Boylan, A.M.R. Play-based groups for children with cerebral palsy and their parents: A qualitative interview study about the impact on mothers’ well-being. Child Care Health Dev. 2022, 48, 578–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elangkovan, I.T.; Shorey, S. Experiences and needs of parents caring for children with cerebral palsy: A systematic review. J. Dev. Behav. Pediatr. 2020, 41, 730–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes, G.; de Jung, B.; Nobre, C.; de Oliveira Norberg, P.; Hirsch, C.; Dresch, F. Social support network of the family for the care of children with cerebral palsy. Rev. Enferm. 2019, 27, 40274. [Google Scholar]

- Younan, E.; McIntyre, S.; Garrity, N.; Karim, T.; Wallace, M.; Gross, P.; Goldsmith, S. Involving people with lived experience when setting cerebral palsy research priorities: A scoping review. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 2025, 67, 725–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| n | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Male | 22 | 23% |

| Female | 75 | 77% |

| Perspective | ||

| Family member/caregiver | 31 | 32% |

| Adult with cerebral palsy | 11 | 11% |

| Healthcare professional | 39 | 40% |

| Other | 16 | 17% |

| Race 1 | ||

| Native American Indian or Alaska Native | 5 | 5% |

| Asian | 4 | 4% |

| Black or African American | 8 | 9% |

| Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander | 0 | 0% |

| White or Caucasian | 70 | 72% |

| Two or More | 5 | 5% |

| Other | 3 | 3% |

| Prefer Not to Answer | 2 | 2% |

| Hispanic, Latino or Spanish Origin 1 | ||

| Yes | 23 | 24% |

| No | 74 | 76% |

| Preferred Language | ||

| English | 94 | 97% |

| Spanish | 3 | 3% |

| Item | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| Yes, changed my perspective of cerebral palsy and early detection | 12 | 75 |

| Yes, changed my perspective of cerebral palsy and early intervention | 9 | 56 |

| Yes, changed my perspective of patient-centered outcomes research | 9 | 56 |

| Yes, changed my approach to caring for individuals with cerebral palsy | 9 | 56 |

| Yes, changed how I advocate for individuals with cerebral palsy | 11 | 69 |

| No | 2 | 13 |

| Other | 1 | 1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Shierk, A.; Clegg, N.J.; Fulton, D.; Delgado, M.R.; Hunt, V.; Bettger, J.; Chapa, S.; Oakley, S.; Roberts, H. Multi-Collaborator Engagement to Identify Research Priorities for Early Intervention in Cerebral Palsy. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 7592. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14217592

Shierk A, Clegg NJ, Fulton D, Delgado MR, Hunt V, Bettger J, Chapa S, Oakley S, Roberts H. Multi-Collaborator Engagement to Identify Research Priorities for Early Intervention in Cerebral Palsy. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(21):7592. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14217592

Chicago/Turabian StyleShierk, Angela, Nancy J. Clegg, Daralyn Fulton, Mauricio R. Delgado, Vanessa Hunt, Janet Bettger, Sydney Chapa, Sadie Oakley, and Heather Roberts. 2025. "Multi-Collaborator Engagement to Identify Research Priorities for Early Intervention in Cerebral Palsy" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 21: 7592. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14217592

APA StyleShierk, A., Clegg, N. J., Fulton, D., Delgado, M. R., Hunt, V., Bettger, J., Chapa, S., Oakley, S., & Roberts, H. (2025). Multi-Collaborator Engagement to Identify Research Priorities for Early Intervention in Cerebral Palsy. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(21), 7592. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14217592