A Randomized Controlled Trial of an Enhanced Version of a Cognitive–Behavioral Video Game Intervention Aimed at Promoting Active Aging: Assessments of Perceived Health and Healthy Lifestyle Habits at Pre- and Post-Intervention

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design

2.2. Participants

2.3. Sample Size

2.4. Instruments

2.5. Interventions

2.5.1. Cognitive–Behavioral Intervention via Interactive Multimedia Online Serious Video Game with Complementary Smartphone App (CBI-V)

2.5.2. Control Group (CG)

2.6. Data Analysis

3. Results

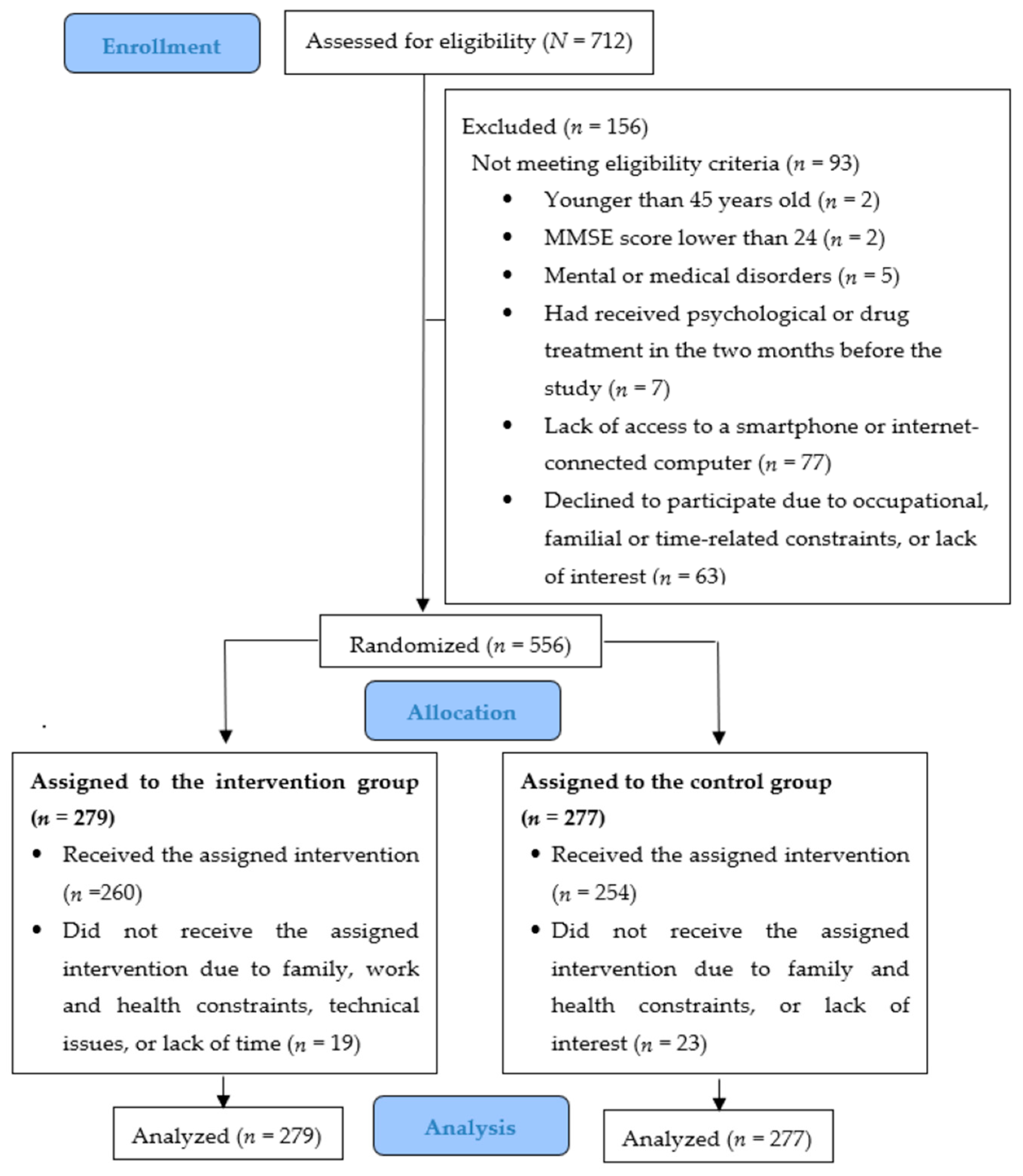

3.1. Participant Flow

3.2. Sociodemographic Characteristics of the Sample

3.3. Effects of the Intervention

3.3.1. Perceived Health

3.3.2. Healthy Habits

3.4. Clinically Significant Change

3.4.1. Perceived Health

3.4.2. Healthy Habits

3.5. Dropouts, Adherence, and Satisfaction with the Intervention

3.5.1. Dropouts

3.5.2. Adherence

3.5.3. Satisfaction

4. Discussion

4.1. Principal Findings

4.2. Implications

4.3. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BPAAT | Brief Physical Activity Assessment Tool for Primary Care Consultations |

| CBI-V | Cognitive-behavioral intervention via an interactive multimedia online video game with a complementary smartphone app |

| CG | Control group |

| CSQ-8 | Client Satisfaction Questionnaire |

| GAMAPEA | Gamificación aplicada a la promoción del envejecimiento activo [Gamification applied to the promotion of active aging] |

| LMM | Linear Mixed Models |

| MINI | Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview |

| MMSE | Mini-Mental State Examination |

| RCT | Randomized Controlled Trial |

| REAP-S | Rapid Eating Assessment for Participants-Short Version |

| SF-36 | Short-Form Health Survey |

| SHI | Sleep Hygiene Index |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

References

- Eurostat. Population on 1st January by Age, Sex and Type of Projection. 2023. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/view/proj_23np/default/table?lang=en (accessed on 3 January 2025).

- World Health Organization. Preparing for an Ageing Population [Fact Sheet]. 2019. Available online: https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/327298 (accessed on 3 January 2025).

- Shen, X.; Wang, C.; Zhou, X.; Zhou, W.; Hornburg, D.; Wu, S.; Snyder, M.P. Nonlinear dynamics of multi-omics profiles during human aging. Nat. Aging 2024, 4, 1619–1634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fjell, A.M.; Walhovd, K.B. Structural brain changes in aging: Courses, causes and cognitive consequences. Rev. Neurosci. 2010, 21, 187–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Active Ageing: A Policy Framework. 2002. Available online: https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/67215 (accessed on 3 January 2025).

- Schaie, K.W. Developmental Influences on Adult Intelligence: The Seattle Longitudinal Study; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Brooks-Wilson, A.R. Genetics of healthy aging and longevity. Hum. Genet. 2013, 132, 1323–1338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Vitiello, M.V.; Gooneratne, N.S. Sleep in normal aging. Sleep Med. Clin. 2018, 13, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S.; Wu, L.; Si, H.; Li, M.; Liu, Y.; Shen, B. Association between nighttime sleep duration and quality with knee osteoarthritis in middle-aged and older Chinese: A longitudinal cohort study. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2024, 118, 105284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, C.; Zhang, R.; Wang, C.; Fu, R.; Song, W.; Dou, K.; Wang, S. Sleep quality and risk of cancer: Findings from the English longitudinal study of aging. Sleep 2021, 44, zsaa192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadier, K.; Qin, L.; Ainiwaer, A.; Rehemuding, R.; Dilixiati, D.; Du, Y.Y.; Maimaiti, H.; Ma, X.; Ma, Y.T. Association of sleep-related disorders with cardiovascular disease among adults in the United States: A cross-sectional study based on national health and nutrition examination survey 2005–2008. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2022, 9, 954238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tworoger, S.S.; Lee, S.; Schernhammer, E.S.; Grodstein, F. The association of self-reported sleep duration, difficulty sleeping, and snoring with cognitive function in older women. Alzheimer Dis. Assoc. Disord. 2006, 20, 41–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nystoriak, M.A.; Bhatnagar, A. Cardiovascular effects and benefits of exercise. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2018, 5, 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lachman, S.; Boekholdt, S.M.; Luben, R.N.; Sharp, S.J.; Brage, S.; Khaw, K.T.; Peters, R.J.; Wareham, N.J. Impact of physical activity on the risk of cardiovascular disease in middle-aged and older adults: EPIC Norfolk prospective population study. Eur. J. Prev. Cardiol. 2018, 25, 200–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peterson, M.D.; Rhea, M.R.; Sen, A.; Gordon, P.M. Resistance exercise for muscular strength in older adults: A meta-analysis. Ageing Res. Rev. 2010, 9, 226–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schättin, A.; Gennaro, F.; Egloff, M.; Vogt, S.; de Bruin, E.D. Physical activity, nutrition, cognition, neurophysiology, and short-time synaptic plasticity in healthy older adults: A cross-sectional study. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2018, 10, 242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, K.; Yang, Q.; Wang, J.; Zeng, B. Accelerometer-derived physical activity, sedentary behavior, and the risk of depression and anxiety in middle-aged and older adults: A prospective cohort study of 71,556 UK Biobank participants. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2025, 33, 512–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martínez-González, M.A.; Martín-Calvo, N. Mediterranean diet and life expectancy; beyond olive oil, fruits, and vegetables. Curr. Opin. Clin. Nutr. Metab. Care 2016, 19, 401–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rizzoli, R.; Boonen, S.; Brandi, M.L.; Bruyère, O.; Cooper, C.; Kanis, J.A.; Kaufman, J.M.; Ringe, J.D.; Weryha, G.; Reginster, J.Y. Vitamin D supplementation in elderly or postmenopausal women: A 2013 update of the 2008 recommendations from the European Society for Clinical and Economic Aspects of Osteoporosis and Osteoarthritis (ESCEO). Curr. Med. Res. Opin. 2013, 29, 305–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Good Health Adds Life to Years. 2012. Available online: https://www.who.int/news/item/03-04-2012-world-health-day-2012---good-health-adds-life-to-years (accessed on 3 January 2025).

- Brach, M.; de Bruin, E.D.; Levin, O.; Hinrichs, T.; Zijlstra, W.; Netz, Y. Evidence-based yet still challenging! Research on physical activity in old age. Eur. Rev. Aging Phys. Act. 2023, 20, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeSmet, A.; Van Ryckeghem, D.; Compernolle, S.; Baranowski, T.; Thompson, D.; Crombez, G.; Poels, K.; Van Lippevelde, W.; Bastiaensens, S.; Van Cleemput, K.; et al. A meta-analysis of serious digital games for healthy lifestyle promotion. Prev. Med. 2014, 69, 95–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vázquez, F.L.; Otero, P.; García-Casal, J.A.; Blanco, V.; Torres, Á.J.; Arrojo, M. Efficacy of video game-based interventions for active aging: A systematic literature review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0208192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahlbaugh, P.E.; Sperandio, A.J.; Carlson, A.L.; Hauselt, J. Effects of playing Wii on well-being in the elderly: Physical activity, loneliness, and mood. Act. Adapt. Aging 2011, 35, 331–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karahan, A.Y.; Tok, F.; Taşkın, H.; Kuçuksaraç, S.; Başaran, A.; Yıldırım, P. Effects of exergames on balance, functional mobility, and quality of life of geriatrics versus home exercise programme: Randomized controlled study. Cent. Eur. J. Public Health 2015, 23, S14–S18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maillot, P.; Perrot, A.; Hartley, A.; Do, M.C. The braking force in walking: Age-related differences and improvement in older adults with exergame training. J. Aging Phys. Act. 2014, 22, 518–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duque, G.; Boersma, D.; Loza-Diaz, G.; Hassan, S.; Suarez, H.; Geisinger, D.; Suriyaarachchi, P.; Sharma, A.; Demontiero, O. Effects of balance training using a virtual reality- system in older fallers. Clin. Interv. Aging 2013, 8, 257–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montero-Alía, P.; Miralles-Basseda, R.; López-Jiménez, T.; Muñoz-Ortiz, L.; Jiménez-González, M.; Prat-Rovira, J.; Albarrán-Sánchez, J.L.; Manresa-Domínguez, J.M.; Andreu-Concha, C.M.; Rodríguez-Pérez, M.C.; et al. Controlled trial of balance training using a video game console in community-dwelling older adults. Age Ageing 2019, 48, 506–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otero, P.; Cotardo, T.; Blanco, V.; Vázquez, F.L. Development of a videogame for the promotion of active aging through depression prevention, healthy lifestyle habits, and cognitive stimulation for middle-to-older aged adults. Games Health J. 2021, 10, 264–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanco, V.; Otero, P.; Cotardo, T.; Bouza, Q.; Torres, Á.J.; Vázquez, F.L. Efficacy of a video game for promoting active and healthy aging (initial version): A randomized controlled trial. BMC Public Health 2025, in press. [Google Scholar]

- Otero, P.; Cotardo, T.; Blanco, V.; Torres, Á.J.; Simón, M.A.; Bueno, A.M.; Vázquez, F.L. A randomized controlled pilot study of a cognitive-behavioral video game intervention for the promotion of active aging. Digit. Health 2024, 10, 20552076241233139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopewell, S.; Chan, A.-W.; Collins, G.S.; Hróbjartsson, A.; Moher, D.; Schulz, K.F.; Tunn, R.; Aggarwal, R.; Berkwits, M.; Berlin, J.A.; et al. CONSORT 2025 Statement: Updated guideline for reporting randomized trials. BMJ 2025, 389, e081123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folstein, M.F.; Folstein, S.E.; McHugh, P.R. Minimental state: A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J. Psychiatr. Res. 1975, 12, 189–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lobo, A.; Saz, P.; Marcos, G.; Día, J.L.; de la Cámara, C.; Ventura, T.; Morales, F.; Pascual, L.F.; Montañés, J.A.; Aznar, S.; et al. Revalidación y normalización del Mini-Examen Cognoscitivo (primera versión en castellano del Mini-Mental Status Examination) en la población general geriátrica [Revalidation and standardization of the cognition mini-exam (first Spanish versión of the Mini-Mental Status Examination) in the general geriatric population]. Med. Clin. 1999, 112, 767–774. [Google Scholar]

- Cummings, S.R.; Grady, D.G.; Huang, A.J. Designing randomized blinded trials. In Designing Clinical Research, 5th ed.; Browner, W.S., Newman, T.B., Cummings, S.R., Grady, D.G., Huang, A.J., Kanaya, A.M., Pletcher, M.J., Eds.; Wolters Kluwer: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2023; pp. 196–220. [Google Scholar]

- Sheehan, D.V.; Lecrubier, Y.; Sheehan, K.H.; Amorim, P.; Janavs, J.; Weiller, E.; Hergueta, T.; Baker, R.; Dunbar, G.C. The Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (M.I.N.I): The development and validation of a structured diagnostic psychiatric interview for DSM-IV and ICD-10. J. Clin. Psychiatry 1998, 59, 22–33. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ferrando, L.; Bobes, J.; Gibert, J.; Soto, M.; Soto, O. MINI. Entrevista Neuropsiquiátrica Internacional. Versión en Español 5.0.0. DSM-IV; [MINI International Neuropsychiatric Interview. Spanish Version 5.0.0. DSM-IV]; Instituto IAP: Madrid, Spain, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Ware, J.E.; Sherbourne, C.D. The MOS 36-item Short-Form Health Survey (SF-36): I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Med. Care 1992, 30, 473–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alonso, J.; Prieto, L.; Antó, J.M. La versión española del SF-36 Health Survey (Cuestionario de Salud SF-36): Un instrumento para la medida de los resultados clínicos [The Spanish version of the SF-36 Health Survey: A measure of clinical outcomes]. Med. Clin. 1995, 104, 771–776. [Google Scholar]

- Mastin, D.F.; Bryson, J.; Corwyn, R. Assessment of sleep hygiene using the Sleep Hygiene Index. J. Behav. Med. 2006, 29, 223–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marshall, A.L.; Smith, B.J.; Bauman, A.E.; Kaur, S. Reliability and validity of a brief physical activity assessment for use by family doctors. Br. J. Sports Med. 2005, 39, 294–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Puig, A.; Peña, O.; Romaguera, M.; Duran, E.; Heras, A.; Solà, M.; Sarmiento, M.; Cid, A. Cómo identificar la inactividad física en atención primaria: Validación de las versiones catalana y española de 2 cuestionarios breves [How to identify physical inactivity in primary care: Validation of the Catalan and Spanish versions of 2 short questionnaires]. Aten. Primaria 2012, 44, 485–493. [Google Scholar]

- Segal-Isaacson, C.J.; Wylie-Rosett, J.; Gans, K.M. Validation of a short dietary assessment questionnaire: The Rapid Eating and Activity Assessment for Participants Short version (REAP-S). Diabetes Educ. 2004, 30, 774–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Larsen, D.L.; Attkisson, C.C.; Hargreaves, W.A.; Nguyen, T.D. Assessment of client/patient satisfaction: Development of a general scale. Eval. Program. Plann. 1979, 2, 197–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vázquez, F.L.; Torres, Á.; Otero, P.; Blanco, V.; Attkisson, C.C. Psychometric properties of the Castilian Spanish version of the Client Satisfaction Questionnaire (CSQ-8). Curr. Psychol. 2019, 38, 829–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vázquez, F.L.; Torres, Á.J.; Otero, P.; Blanco, V.; López, L.; García-Casal, A.; Arrojo, M. Cognitive-behavioral intervention via interactive multimedia online video game for active aging: Study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials 2019, 20, 692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewinsohn, P.M.; Hoberman, H.; Teri, L.; Hautzinger, M. An integrative theory of depression. In Theoretical Issues in Behaviour Therapy; Reiss, S., Bootzin, R.R., Eds.; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 1985; pp. 331–359. [Google Scholar]

- Vázquez, F.L.; Hermida, E.; Torres, Á.; Otero, P.; Blanco, V.; Díaz, O. Efficacy of a brief cognitive-behavioral intervention in caregivers with high depressive symptoms. Behav. Psychol. 2014, 22, 79–96. [Google Scholar]

- Vázquez, F.L.; Torres, Á.; Blanco, V.; Otero, P.; Díaz, O.; Ferraces, M.J. Long-term follow-up of a randomized clinical trial assessing the efficacy of a brief cognitive-behavioral depression prevention intervention for caregivers with elevated depressive symptoms. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2016, 24, 421–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vázquez, F.L.; López, L.; Torres, Á.J.; Otero, P.; Blanco, V.; Díaz, O.; Páramo, M. Analysis of the components of a cognitive-behavioral intervention for the prevention of depression administered via conference call to nonprofessional caregivers: A randomized controlled trial. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 2067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López, L.; Vázquez, F.L.; Torres, Á.J.; Otero, P.; Blanco, V.; Díaz, O.; Páramo, M. Long-term effects of a cognitive behavioral conference call intervention on depression in non-professional caregivers. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 8329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vázquez, F.L.; Blanco, V.; Hita, I.; Torres, Á.J.; Otero, P.; Páramo, M.; Salmerón, M. Efficacy of a cognitive behavioral intervention for the prevention of depression in nonprofessional caregivers administered through a smartphone app: A randomized controlled trial. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 5872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. Social Foundations of Thought and Action: A Social Cognitive Theory; Prentice Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Spiegler, M.D. Contemporary Behavior Therapy, 6th ed.; Cengage Learning: Boston, MA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Tucker, A.M.; Stern, Y. Cognitive reserve in aging. Curr. Alzheimer Res. 2011, 8, 354–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shapiro, M. Plasticity, hippocampal place cells, and cognitive maps. Arch. Neurol. 2001, 58, 874–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Light, L.L. Memory and aging: Four hypotheses in search of data. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 1991, 42, 333–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rubin, D.B. Multiple Imputation for Nonresponse in Surveys; John Wiley & Sons: New York, NY, USA, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences, 2nd ed.; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: Hillsdale, NJ, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Jacobson, N.S.; Follette, W.C.; Revenstorf, D. Psychotherapy outcome research: Methods for reporting variability and evaluating clinical significance. Behav. Therapy 1984, 15, 336–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobson, N.S.; Truax, P. Clinical significance: A statistical approach to defining meaningful change in psychotherapy research. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 1991, 59, 12–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baranowski, T.; Buday, R.; Thompson, D.I.; Baranowski, J. Playing for real: Video games and stories for health-related behavior change. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2008, 34, 74–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shearer-Underhill, C.; Marker, C. The use of the Number Needed to Treat (NNT) in randomized clinical trials in psychological treatment. Clin. Psychol. Sci. Pract. 2010, 17, 41–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bender, R. Number needed to treat (NNT). In Encyclopedia of Biostatistics; Armitage, P., Colton, T., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons: Chichester, UK, 2005; pp. 3752–3761. [Google Scholar]

- Manser, P.; Herold, F.; de Bruin, E.D. Components of effective exergame-based training to improve cognitive functioning in middle-aged to older adults—A systematic review and meta-analysis. Ageing Res. Rev. 2024, 99, 102385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres, A.C.S. Cognitive effects of video games on old people. Int. J. Disabil. Hum. Dev. 2011, 10, 55–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raz, N.; Lindenberger, U.; Rodrigue, K.M.; Kennedy, K.M.; Head, D.; Williamson, A.; Dahle, C.; Gerstorf, D.; Acker, J.D. Regional brain changes in aging healthy adults: General trends, individual differences and modifiers. Cereb. Cortex 2005, 15, 1676–1689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pew Research Center. Share of Those 65 and Older Who Are Tech Users Has Grown in the Past Decade. 2022. Available online: https://www.pewresearch.org/short-reads/2022/01/13/share-of-those-65-and-older-who-are-tech-users-has-grown-in-the-past-decade/ (accessed on 17 February 2025).

- Statista. Share of Smartphone Users in the United Kingdom (UK) 2012–2024, by Age. 2025. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/300402/smartphoneusageintheukbyage/ (accessed on 17 February 2025).

| Module | Intervention Group | Control Group | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | From Roncesvalles to Pamplona. The main character (Jacobo) is presented. He is depressed and starts the French Way of the Santiago de Compostela pilgrimage. He receives a (magical) book that guides him through the stages, explaining the interconnections between behavior, thoughts, and emotions. Jacobo encounters characters who provide him with lessons and guidance, such as monitoring his mood, relaxation techniques, and cognitive training tasks (puzzles). | Contents: Emotional regulation Mood self-monitoring Learning to relax Techniques/strategies:

| Tasks between modules (app): Daily self-monitoring of mood Relaxation through diaphragmatic breathing | Aging Contents: Population aging The aging process Consequences of aging Active aging |

| 2 | From Pamplona to Estella. Jacobo learns about the legend of the Reniega Fountain. Suddenly, he is attacked by Belfegor (one of Lucifer’s henchmen), who steals the book. To get the book back, Jacobo is given instructions to find nine sets of ‘‘emotional vitamins’’ hidden within scallop shells that symbolize the Way. For this purpose, he must complete cognitive training tasks. Finally, he gets the book back. Another pilgrim teaches him self-reinforcement and how to apply it. | Contents: Behavioral activation Techniques/strategies:

| Tasks between modules (app): The previous ones plus the following: Elaborating on a list of pleasant activities | Depression Contents: What is depression? Prevalence of depression Evolution of depression Consequences of depression Conclusions |

| 3 | From Estella to Nájera. Jacobo experiences difficulties with sleep, and different characters provide him with strategies to improve his sleep hygiene. They also teach him how to schedule pleasant activities and establish behavioral contracts with himself. Through these efforts, he declares war on Dysnergy. To defeat her, he must find the Tau cross by solving cognitive training tasks. In the end, Jacobo battles and prevails over Dysnergy. | Contents: Learning healthy sleep habits Increasing pleasant activities Techniques/strategies:

| Tasks between modules (app): The previous ones plus the following: Implementing scheduled pleasant activities | Sleep Contents: Sleep phases Changes in sleep related to aging Main sleep problems Prevalence of sleep problems Treatment of sleep problems Conclusions |

| 4 | From Nájera to Burgos. Jacobo’s mood is improving. Jacobo and Guillén (a fellow pilgrim) are ambushed by Dysnergy and Moribilius, who steal the book. With the support of Templar monks, they fight back and receive recommendations on physical activity for maintaining a healthy physical condition. To progress, cognitive training tasks (puzzles) must be solved. Later, they fight against Dysnergy, defeat her, and recover the book. However, Morbilius manages to escape. | Contents: Building a personal physical activity plan Techniques/strategies:

| Tasks between modules (app): The previous ones plus the following: Implementing the personal plan to accomplish the weekly physical activity goal Self-reinforcement | Physical Exercise Contents: Sedentary lifestyle Physical activity Physical activity in middle to old age Relevance of physical activity for health Conclusions |

| 5 | From Burgos to Sahagún. After solving cognitive tasks (puzzles), the book provides key information on healthy eating habits. Jacobo and Guillén meet Culinuris. Morbilius appears, kidnaps Culinuris’ niece, and steals the book. Culinuris states that they must find three colored feathers to defeat Morbilius. Jacobo and Guillén obtain them after completing memory exercises focused on healthy eating. They then confront Morbilius, defeat him, rescue the niece, and get the book back. Guillén decides to settle down, while Jacobo continues his pilgrimage. | Contents: Improving dietary habits Techniques/strategies:

| Tasks between modules (app): The previous ones plus the following: Self-recording of daily meals | Diet Contents: Diet Healthy eating Healthy eating in middle to old age Conclusions |

| 6 | From Sahagún to Rabanal. The book explains the role of thoughts, their impact on mood, and how to detect dysfunctional thoughts. Jacobo encounters the architect Antón Gaudín, who supports him in addressing cognitive distortions. They join forces to battle the gargoyles of the Episcopal Palace of Astorga. Afterwards, Jacobo practices these cognitive restructuring skills with fellow pilgrims at the hostel. | Contents: Relationship between thoughts and mood Cognitive distortions (polarized thinking, catastrophizing, personalization) Techniques/strategies:

| Tasks between modules (app): The previous ones plus the following: Daily tracking and personalized feedback to improve eating habits Detection of negative thoughts | Thoughts Contents: The structure of thought Relationship between thought and mood Types of thoughts Thoughts in middle to old age Controlling negative thoughts and staying calm Conclusions |

| 7 | Fom Rabanal to Triacastela. The Cognitive Distorters (Lucifer’s henchmen) attack Jacobo. Various allies teach Jacobo to replace his negative thoughts with more rational and positive alternatives using specific cognitive techniques: the direct approach, ‘‘the worst that could happen”, “survey” and “how does it help me to think like this”. Jacobo defeats the Cognitive Distorters. | Contents: Cognitive distortions (selective abstraction, mind reading, fortune-telling, “must” or “should” statements) Breaking negative thought patterns Techniques/strategies:

| Tasks between modules (app): The previous ones plus the following: Implementing and recording cognitive restructuring strategies | Cognitive processes Contents: Cognitive processes Cognitive changes in middle to old age Cognitive impairment Relevance of cognitive training Conclusions |

| 8 | From Triacastela to Santiago de Compostela. In the final stage, Jacobo is taught how to cultivate and strengthen the tree of self-esteem. Lucifer appears, with whom Jacobo battles. All the characters that Jacobo has encountered throughout the journey reappear, each contributing their teachings to help him defeat Lucifer. Jacobo then makes an offering to Saint James, who grants him the Compostela (certificate of completion of the Way of Saint James) as recognition for completing the pilgrimage and acquiring healthy lifestyle habits. Jacobo sets out to begin a new life equipped with more optimism, self-knowledge, and practical strategies for well-being. | Contents: Strengthening self-esteem Review of learned content Techniques/strategies:

| Social relations Contents: Social relations Social relationships in middle to old age Primary and secondary social relations The impact of social relationships on health Conclusions | |

| Characteristics | Total n = 556 | CBI-V n = 279 | CG n = 277 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| Sex | ||||||

| Male | 143 | 25.7 | 78 | 28.0 | 65 | 23.5 |

| Female | 413 | 74.3 | 201 | 72.0 | 212 | 76.5 |

| Age | ||||||

| M (SD) | 60.8 (8.0) | 61.0 (7.8) | 60.6 (8.1) | |||

| Range | 45–85 | 45–85 | 45–81 | |||

| Marital status | ||||||

| Single | 197 | 35.4 | 95 | 34.0 | 102 | 36.8 |

| Partnered | 359 | 64.6 | 184 | 66.0 | 175 | 63.2 |

| Education level | ||||||

| Primary | 82 | 14.7 | 36 | 12.9 | 46 | 16.6 |

| Secondary | 149 | 26.8 | 79 | 28.3 | 70 | 25.3 |

| University | 325 | 58.5 | 164 | 58.8 | 161 | 58.1 |

| Main activity | ||||||

| Bachelor’s, certificate holders, technicians, artists | 152 | 27.3 | 81 | 29.0 | 71 | 25.6 |

| Skilled and unskilled workers | 97 | 17.5 | 48 | 17.2 | 49 | 17.7 |

| Homemakers, unemployed, retired | 307 | 55.2 | 150 | 53.8 | 157 | 56.7 |

| Monthly family income | ||||||

| ≤EUR 999 | 59 | 10.6 | 31 | 11.1 | 28 | 10.1 |

| EUR 1000–EUR 1999 | 194 | 34.9 | 102 | 36.6 | 92 | 33.2 |

| ≥EUR 2000 | 303 | 54.5 | 146 | 52.3 | 157 | 56.7 |

| CBI-V Group (n = 279) | Pre- Intervention M (SD) | Post- Intervention M (SD) | t | p | Cohen’s d (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SF-36 | General Health | 66.7 (1.2) | 70.5 (1.2) | −3.836 | <0.001 | −0.195 (−0.295, −0.095) |

| Body Pain | 73.0 (1.4) | 73.8 (1.4) | −0.662 | 0.508 | −0.037 (−0.149, 0.074) | |

| Physical Functioning | 84.5 (1.0) | 85.4 (1.0) | −1.169 | 0.243 | −0.060 (−0.162, 0.041) | |

| Physical Role | 80.5 (1.9) | 81.5 (2.0) | −0.453 | 0.650 | −0.029 (−0.156, 0.098) | |

| Vitality | 65.2 (1.2) | 66.8 (1.3) | −1.475 | 0.141 | −0.076 (−0.177, 0.025) | |

| Social Functioning | 88.5 (1.2) | 86.9 (1.3) | 1.204 | 0.229 | 0.076 (−0.048, 0.200) | |

| Emotional Role | 86.0 (1.9) | 83.8 (1.9) | 1.110 | 0.267 | 0.071 (−0.054, 0.196) | |

| Mental Health | 76.2 (1.0) | 78.7 (1.1) | −2.469 | 0.014 | −0.138 (−0.247, −0.028) | |

| Physical Summary Index | 48.6 (0.5) | 49.3 (0.5) | −1.735 | 0.083 | −0.090 (−0.192, 0.012) | |

| Mental Summary Index | 50.5 (0.6) | 50.4 (0.6) | 0.058 | 0.953 | 0.003 (−0.108, 0.114) | |

| Lifestyle habits | SHI | 11.9 (0.3) | 10.3 (0.3) | 5.959 | <0.001 | 0.319 (0.214, 0.424) |

| BPAAT | 3.5 (0.1) | 4.3 (0.2) | −5.423 | <0.001 | −0.322 (−0.439, −0.206) | |

| REAP-S | 32.6 (0.2) | 34.0 (0.2) | −6.122 | <0.001 | −0.419 (−0.553, −0.285) | |

| CG (n = 277) | Pre- Intervention M (SD) | Post- Intervention M (SD) | t | p | Cohen’s d (95% CI) | |

| SF-36 | General Health | 66.6 (1.2) | 65.7 (1.2) | 0.975 | 0.330 | 0.050 (−0.050, 0.149) |

| Body Pain | 72.2 (1.4) | 70.1 (1.4) | 1.592 | 0.112 | 0.092 (−0.021, 0.205) | |

| Physical Functioning | 85.4 (1.0) | 83.6 (1.0) | 2.115 | 0.035 | 0.110 (0.008, 0.212) | |

| Physical Role | 80.3 (1.9) | 76.4 (2.0) | 1.837 | 0.067 | 0.123 (−0.008, 0.254) | |

| Vitality | 65.6 (1.3) | 64.8 (1.3) | 0.771 | 0.441 | 0.042 (−0.066, 0.151) | |

| Social Functioning | 85.1 (1.2) | 83.4 (1.3) | 1.270 | 0.204 | 0.084 (−0.046, 0.215) | |

| Emotional Role | 83.1 (1.9) | 80.4 (2.0) | 1.314 | 0.189 | 0.085 (−0.042, 0.213) | |

| Mental Health | 74.4 (1.1) | 74.8 (1.1) | −0.459 | 0.646 | −0.027 (−0.140, 0.087) | |

| Physical Summary Index | 49.0 (0.5) | 47.9 (0.5) | 2.478 | 0.013 | 0.132 (0.027, 0.236) | |

| Mental Summary Index | 49.0 (0.6) | 48.7 (0.7) | 0.548 | 0.584 | 0.032 (−0.084, 0.149) | |

| Lifestyle habits | SHI | 12.3 (0.3) | 12.0 (0.3) | 1.030 | 0.304 | 0.319 (0.214, 0.424) |

| BPAAT | 3.8 (0.1) | 3.9 (0.1) | −0.239 | 0.811 | −0.014 (−0.129, −0.101) | |

| REAP-S | 32.9 (0.2) | 33.0 (0.2) | −0.672 | 0.502 | −0.047 (−0.182, 0.089) | |

| Comparison CBI-V vs. CG | t | p | Cohen’s d (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SF-36 | General Health | −2.760 | <0.001 | −0.248 (−0.424, −0.072) |

| Body Pain | −1.898 | 0.058 | −0.165 (−0.336, 0.006) | |

| Physical Functioning | −1.281 | 0.201 | −0.114 (−0.289, 0.061) | |

| Physical Role | −1.783 | 0.075 | −0.161 (−0.338, 0.016) | |

| Vitality | −1.129 | 0.259 | −0.099 (−0.272, 0.073) | |

| Social Functioning | −1.945 | 0.052 | −0.172 (−0.346, 0.002) | |

| Emotional Role | −1.229 | 0.219 | −0.108 (−0.279, 0.064) | |

| Mental Health | −2.450 | 0.015 | −0.218 (−0.392, −0.043) | |

| Physical Summary Index | −1.928 | 0.054 | −0.171 (−0.345, 0.003) | |

| Mental Summary Index | −1.877 | 0.061 | −0.165 (−0.338, 0.008) | |

| Lifestyle habits | SHI | 3.779 | <0.001 | 0.334 (0.160, 0.507) |

| BPAAT | −2.261 | 0.024 | −0.188 (−0.351, −0.025) | |

| REAP-S | −3.205 | 0.001 | −0.291 (−0.469, −0.113) | |

| Variables | CBI-V n = 279 | CG n = 277 | χ2 | p | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | ||||

| SF-36 | General Health | ||||||

| No clinically significant change | 89 | 31.9 | 113 | 40.8 | 4.75 | 0.029 | |

| Clinically significant change | 190 | 68.1 | 164 | 59.2 | |||

| Body Pain | |||||||

| No clinically significant change | 157 | 56.3 | 167 | 60.3 | 0.92 | 0.337 | |

| Clinically significant change | 122 | 43.7 | 110 | 39.7 | |||

| Physical Functioning | |||||||

| No clinically significant change | 50 | 17.9 | 71 | 25.6 | 4.85 | 0.028 | |

| Clinically significant change | 229 | 82.1 | 206 | 74.4 | |||

| Physical Role | |||||||

| No clinically significant change | 75 | 26.9 | 82 | 29.6 | 0.51 | 0.476 | |

| Clinically significant change | 204 | 73.1 | 195 | 70.4 | |||

| Vitality | |||||||

| No clinically significant change | 89 | 31.9 | 108 | 39.0 | 3.05 | 0.081 | |

| Clinically significant change | 190 | 52.9 | 169 | 61.0 | |||

| Social Functioning | |||||||

| No clinically significant change | 123 | 44.1 | 152 | 54.9 | 6.47 | 0.011 | |

| Clinically significant change | 156 | 55.9 | 125 | 45.1 | |||

| Emotional Role | |||||||

| No clinically significant change | 80 | 28.7 | 109 | 39.4 | 7.06 | 0.008 | |

| Clinically significant change | 199 | 71.3 | 168 | 60.6 | |||

| Mental Health | |||||||

| No clinically significant change | 67 | 24.0 | 90 | 32.5 | 4.93 | 0.026 | |

| Clinically significant change | 212 | 76.0 | 187 | 67.5 | |||

| Physical Summary Index | |||||||

| No clinically significant change | 59 | 21.1 | 85 | 30.7 | 6.59 | 0.010 | |

| Clinically significant change | 220 | 78.9 | 192 | 69.3 | |||

| Mental Summary Index | |||||||

| No clinically significant change | 68 | 24.4 | 84 | 30.3 | 2.48 | 0.115 | |

| Clinically significant change | 211 | 75.6 | 193 | 69.7 | |||

| Lifestyle habits | Sleep hygiene | ||||||

| No clinically significant change | 2 | 0.7 | 10 | 3.6 | 5.39 | 0.020 | |

| Clinically significant change | 275 | 99.3 | 269 | 96.4 | |||

| Physical activity | |||||||

| No clinically significant change | 85 | 30.5 | 104 | 37.5 | 3.11 | 0.078 | |

| Clinically significant change | 194 | 69.5 | 173 | 62.5 | |||

| Eating habits | |||||||

| No clinically significant change | 92 | 33.0 | 118 | 42.6 | 5.48 | 0.019 | |

| Clinically significant change | 187 | 67.0 | 159 | 57.4 | |||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cotardo, T.; Otero, P.; de Bruin, E.D.; Blanco, V.; Arrojo, M.; Páramo, M.; Ferraces, M.J.; Torres, Á.J.; Vázquez, F.L. A Randomized Controlled Trial of an Enhanced Version of a Cognitive–Behavioral Video Game Intervention Aimed at Promoting Active Aging: Assessments of Perceived Health and Healthy Lifestyle Habits at Pre- and Post-Intervention. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 6873. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14196873

Cotardo T, Otero P, de Bruin ED, Blanco V, Arrojo M, Páramo M, Ferraces MJ, Torres ÁJ, Vázquez FL. A Randomized Controlled Trial of an Enhanced Version of a Cognitive–Behavioral Video Game Intervention Aimed at Promoting Active Aging: Assessments of Perceived Health and Healthy Lifestyle Habits at Pre- and Post-Intervention. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(19):6873. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14196873

Chicago/Turabian StyleCotardo, Tania, Patricia Otero, Eling D. de Bruin, Vanessa Blanco, Manuel Arrojo, Mario Páramo, María J. Ferraces, Ángela J. Torres, and Fernando L. Vázquez. 2025. "A Randomized Controlled Trial of an Enhanced Version of a Cognitive–Behavioral Video Game Intervention Aimed at Promoting Active Aging: Assessments of Perceived Health and Healthy Lifestyle Habits at Pre- and Post-Intervention" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 19: 6873. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14196873

APA StyleCotardo, T., Otero, P., de Bruin, E. D., Blanco, V., Arrojo, M., Páramo, M., Ferraces, M. J., Torres, Á. J., & Vázquez, F. L. (2025). A Randomized Controlled Trial of an Enhanced Version of a Cognitive–Behavioral Video Game Intervention Aimed at Promoting Active Aging: Assessments of Perceived Health and Healthy Lifestyle Habits at Pre- and Post-Intervention. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(19), 6873. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14196873