Improved Survival with Improved NAPRC Compliance: A Single-Institution Experience

Abstract

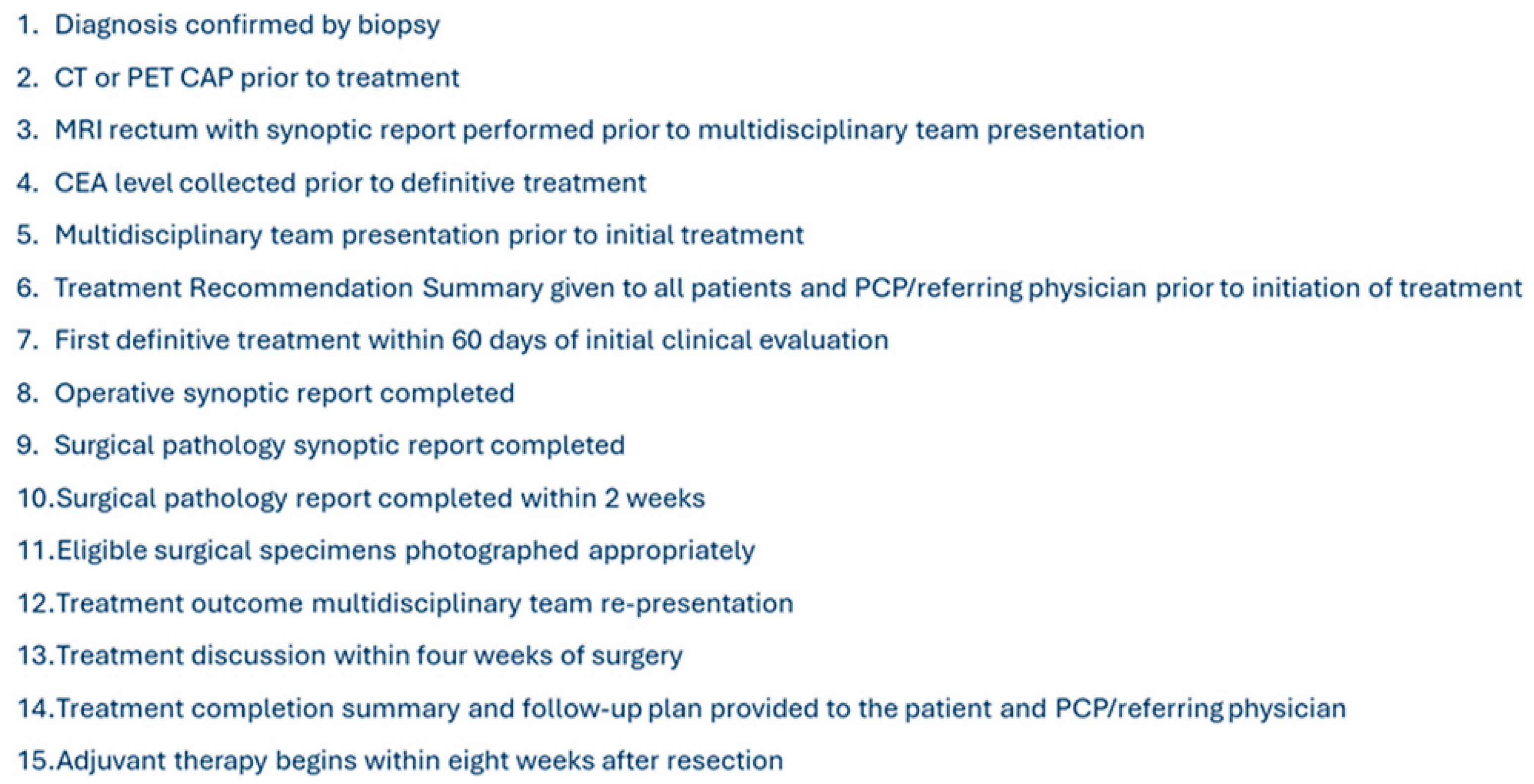

1. Introduction

- Objective:

2. Materials and Methods

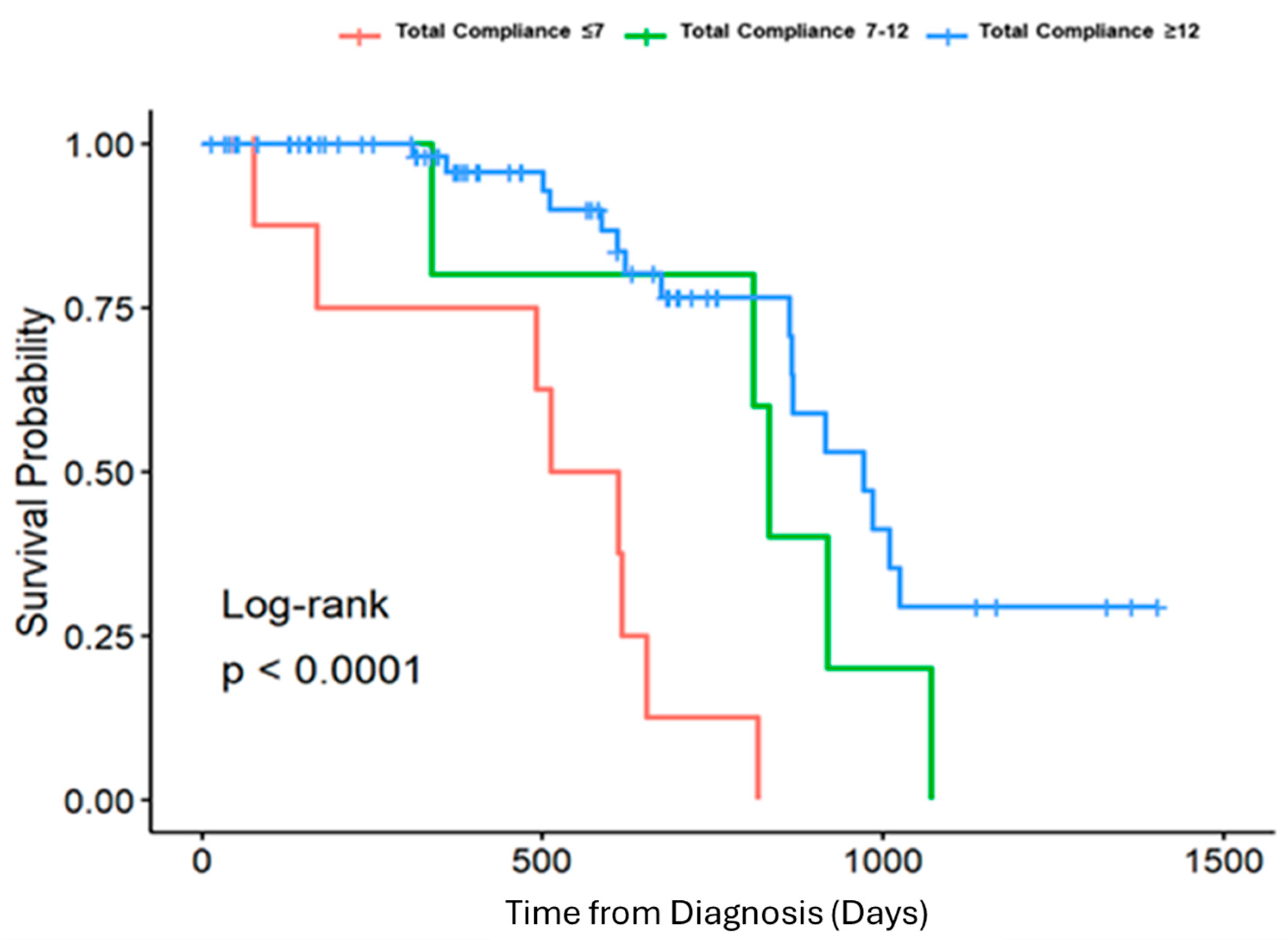

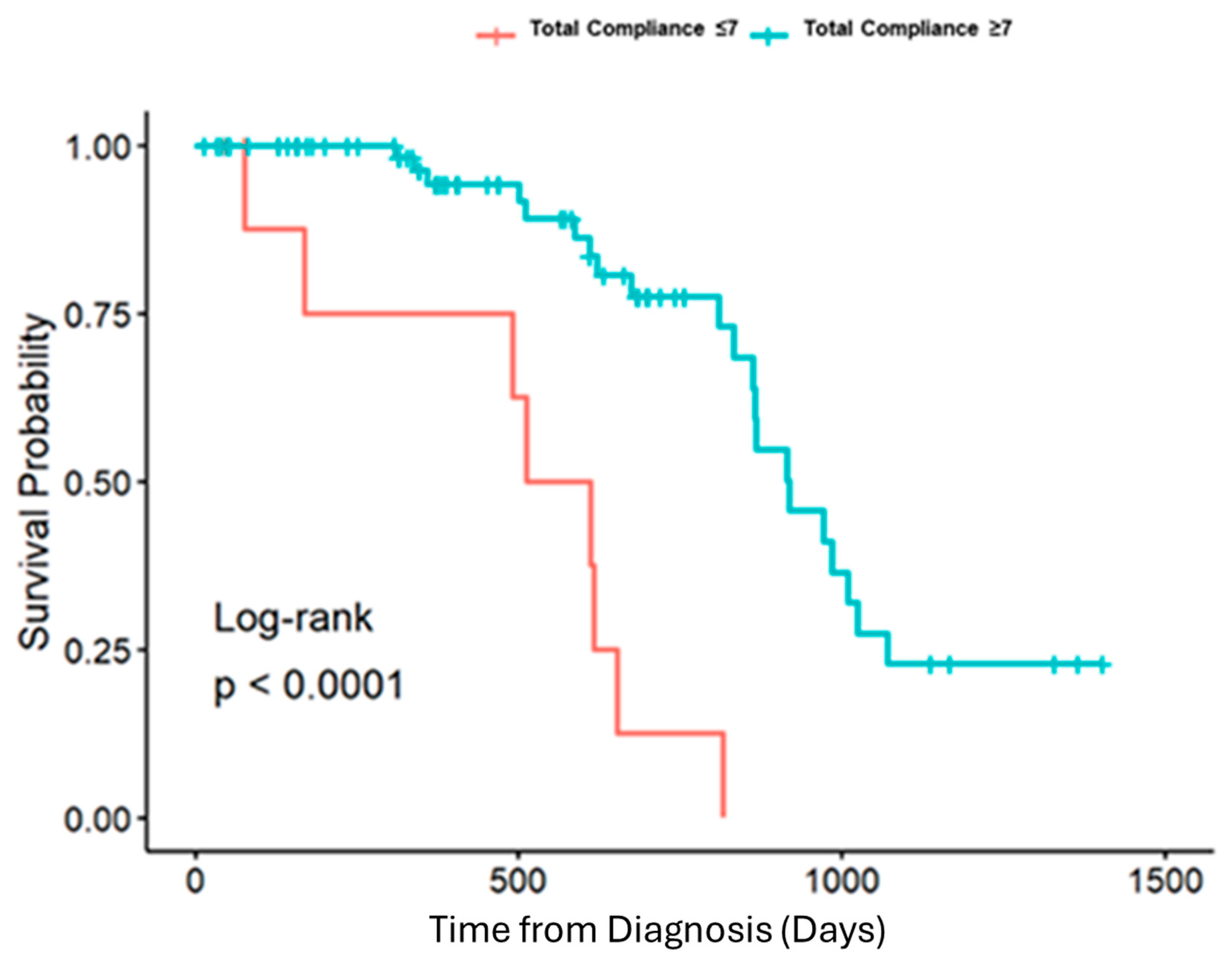

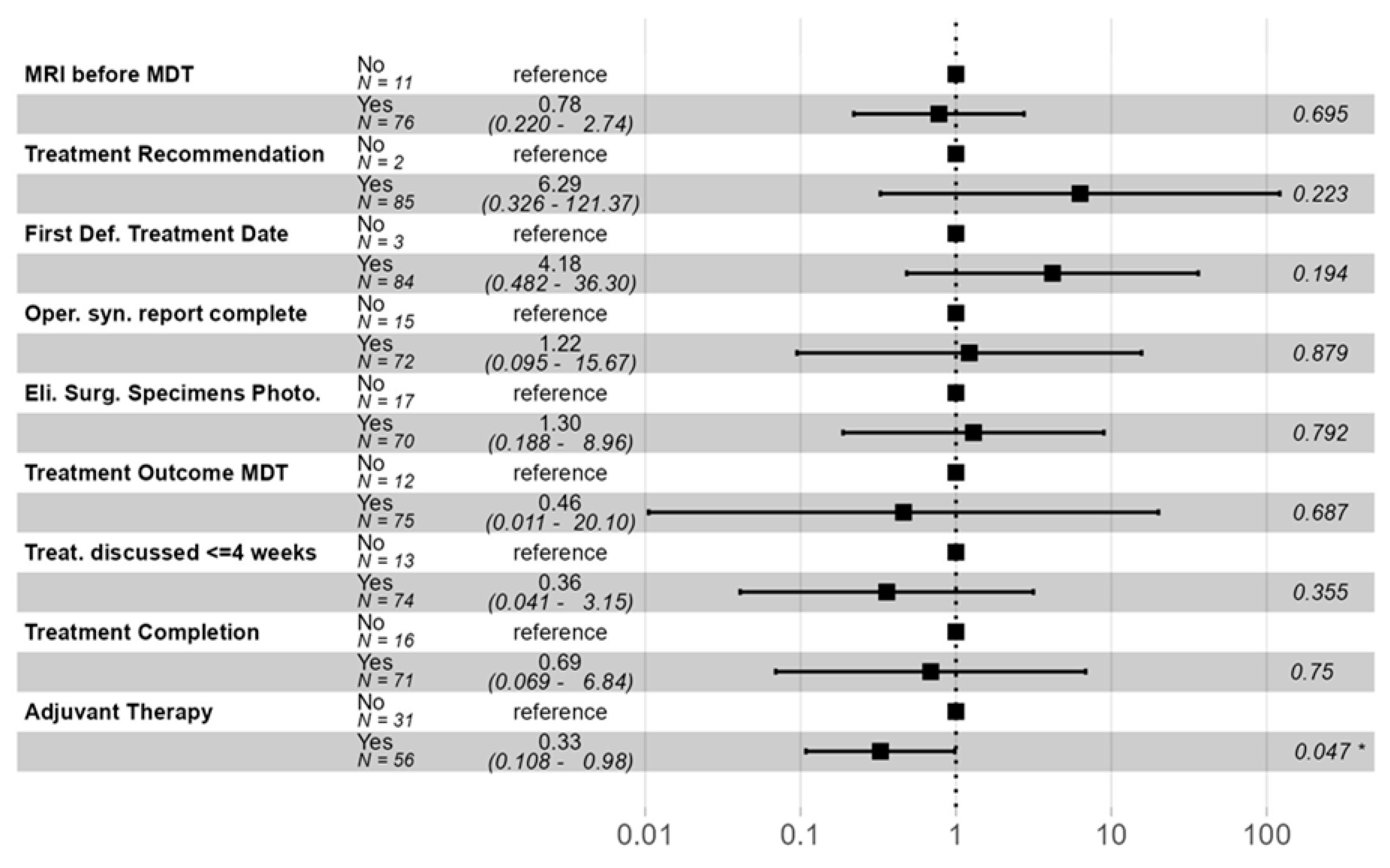

3. Results

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Common Cancer Sites—Cancer Stat Facts. SEER. Available online: https://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/common.html (accessed on 5 February 2025).

- Rickles, A.S.; Dietz, D.W.; Chang, G.J.; Wexner, S.D.; Berho, M.E.; Remzi, F.H.; Greene, F.L.; Fleshman, J.W.; Abbas, M.A.; Peters, W. High Rate of Positive Circumferential Resection Margins Following Rectal Cancer Surgery: A Call to Action. Ann. Surg. 2015, 262, 891–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huo, Y.R.; Phan, K.; Morris, D.L.; Liauw, W. Systematic review and a meta-analysis of hospital and surgeon volume/outcome relationships in colorectal cancer surgery. J. Gastrointest. Oncol. 2017, 8, 534–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ricciardi, R.; Roberts, P.L.; Read, T.E.; Baxter, N.N.; Marcello, P.W.; Schoetz, D.J. Who Performs Proctectomy for Rectal Cancer in the United States? Dis. Colon Rectum 2011, 54, 12104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ricciardi, R.; Roberts, P.L.; Read, T.E.; Marcello, P.W.; Schoetz, D.J.; Baxter, N.N. Variability in reconstructive procedures following rectal cancer surgery in the United States. Dis. Colon Rectum 2010, 53, 874–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Archampong, D.; Borowski, D.; Wille-Jørgensen, P.; Iversen, L.H. Workload and surgeon’s specialty for outcome after colorectal cancer surgery. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2012, 3, CD0053916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dietz, D.W. Multidisciplinary Management of Rectal Cancer: The OSTRICH. J. Gastrointest. Surg. 2013, 17, 1863–1868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, L.; Dietz, D.W.; Fleming, F.J.; Remzi, F.H.; Wexner, S.D.; Winchester, D.; Monson, J.R. Accreditation Readiness in US Multidisciplinary Rectal Cancer Care: A Survey of OSTRICH Member Institutions. JAMA Surg. 2018, 153, 388–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- American College of Surgeons. About NAPRC. Updated 2025. Available online: https://www.facs.org/quality-programs/cancer-programs/national-accreditation-program-for-rectal-cancer/about (accessed on 5 February 2025).

- Locker, G.Y.; Hamilton, S.; Harris, J.; Jessup, J.M.; Kemeny, N.; Macdonald, J.S.; Somerfield, M.R.; Hayes, D.F.; Bast, R.C., Jr. ASCO 2006 update of recommendations for the use of tumor markers in gastrointestinal cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2006, 24, 5313–5327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peters, G.W.; Thomas, G.; Applegarth, J.A.; Wasvary, J.; Bohler, F.; Callahan, R.E.; Wasvary, H.J. The Effect of the Adoption of the National Accreditation Program for Rectal Cancer Process on Compliance Standards at a Single Institution. Am. Surg. 2025, 91, 345–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aggarwal, P.; Hong, C.; Portner, S.; Oommen, S.C. Does Adherence to National Accreditation Program for Rectal Cancer (NAPRC) Process Measures Lead to Better Outcomes in the Management of Rectal Cancer? Initial Experience from the First NAPRC Accredited Center in the Country. J. Am. Coll. Surg. 2021, 233, e24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brady, J.T.; Bingmer, K.; Bliggenstorfer, J.; Xu, Z.; Fleming, F.J.; Remzi, F.H.; Consortium for Optimizing the Treatment of Rectal Cancer (OSTRiCh). Could meeting the standards of the National Accreditation Program for Rectal Cancer in the National Cancer Database improve patient outcomes? Color. Dis. 2023, 25, 916–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harbaugh, C.M.; Kunnath, N.J.; Suwanabol, P.A.; Dimick, J.B.; Hendren, S.K.; Ibrahim, A.M. Association of National Accreditation Program for Rectal Cancer Accreditation with Outcomes After Rectal Cancer Surgery. J. Am. Coll. Surg. 2024, 239, 98–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Total Compliance <= 7 | Total Compliance 8–12 | Total Compliance > 12 | Overall | p-Value | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Death (N = 8) | Survival (N = 2) | Death (N = 5) | Survival (N = 2) | Death (N = 16) | Survival (N = 54) | Death (N = 29) | Survival (N = 58) | ||

| Age at presentation | |||||||||

| Mean (SD) | 62.9 (13.9) | 61.0 (7.07) | 68.6 (16.9) | 59.0 (12.7) | 64.3 (12.9) | 60.6 (11.2) | 64.6 (13.5) | 60.6 (11.0) | 0.662 |

| Median [Min, Max] | 63.5 [41.0, 86.0] | 61.0 [56.0, 66.0] | 78.0 [43.0, 84.0] | 59.0 [50.0, 68.0] | 63.0 [44.0, 84.0] | 62.0 [36.0, 92.0] | 64.0 [41.0, 86.0] | 62.0 [36.0, 92.0] | |

| Sex | |||||||||

| Female | 5 (62.5%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (40.0%) | 1 (50.0%) | 8 (50.0%) | 21 (38.9%) | 15 (51.7%) | 22 (37.9%) | 0.919 |

| Male | 3 (37.5%) | 2 (100%) | 3 (60.0%) | 1 (50.0%) | 8 (50.0%) | 33 (61.1%) | 14 (48.3%) | 36 (62.1%) | |

| Race | |||||||||

| White or Caucasian | 6 (75.0%) | 2 (100%) | 4 (80.0%) | 2 (100%) | 12 (75.0%) | 46 (85.2%) | 22 (75.9%) | 50 (86.2%) | 0.88 |

| Asian | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (3.7%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (3.4%) | |

| Black or African American | 2 (25.0%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (20.0%) | 0 (0%) | 3 (18.8%) | 5 (9.3%) | 6 (20.7%) | 5 (8.6%) | |

| Other | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (6.3%) | 1 (1.9%) | 1 (3.4%) | 1 (1.7%) | |

| Stage | |||||||||

| 1 | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (50.0%) | 1 (6.3%) | 6 (11.1%) | 1 (3.4%) | 7 (12.1%) | 0.166 |

| 2 | 2 (25.0%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (40.0%) | 1 (50.0%) | 4 (25.0%) | 15 (27.8%) | 8 (27.6%) | 16 (27.6%) | |

| 3 | 2 (25.0%) | 2 (100%) | 1 (20.0%) | 0 (0%) | 7 (43.8%) | 28 (51.9%) | 10 (34.5%) | 30 (51.7%) | |

| 4 | 4 (50.0%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (40.0%) | 0 (0%) | 4 (25.0%) | 5 (9.3%) | 10 (34.5%) | 5 (8.6%) | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wasvary, H.; Applegarth, J.A.; Hao, S.; Kowalczyk, T.A.; Nazarian, G.; Bova, C. Improved Survival with Improved NAPRC Compliance: A Single-Institution Experience. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 6872. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14196872

Wasvary H, Applegarth JA, Hao S, Kowalczyk TA, Nazarian G, Bova C. Improved Survival with Improved NAPRC Compliance: A Single-Institution Experience. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(19):6872. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14196872

Chicago/Turabian StyleWasvary, Harry, Jacob A. Applegarth, Scarlett Hao, Tyler A. Kowalczyk, Gayaneh Nazarian, and Claire Bova. 2025. "Improved Survival with Improved NAPRC Compliance: A Single-Institution Experience" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 19: 6872. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14196872

APA StyleWasvary, H., Applegarth, J. A., Hao, S., Kowalczyk, T. A., Nazarian, G., & Bova, C. (2025). Improved Survival with Improved NAPRC Compliance: A Single-Institution Experience. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(19), 6872. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14196872