Abstract

Background/Objectives: Chronic diseases, such as diabetes mellitus, require sustained management and medication adherence to reduce the risk of related complications and mortality. However, the adherence levels are not satisfactory, which could be attributed to several factors, including cultural beliefs and socioeconomic factors. This study aimed to assess the relationship between cultural and socioeconomic factors, patient preferences, and medication adherence among diabetic patients. Methods: A mixed-methods cross-sectional design was implemented using face-to-face questionnaires and personal interviews. This study was conducted in 159 primary healthcare clinics (PHCs) in Madinah, Saudi Arabia, from 26 August 2024 to 10 February 2025. It included type 1 and type 2 diabetic patients. The Morisky Medication Adherence and General Medication Adherence Scales were used to evaluate diabetes medication adherence among the participants. Results: The included 424 diabetic patients had a predominant age range from 40 to 59 (48.1%). The majority were non-smokers (88.7%), Saudi Arabian (94.6%), and female (62.7%). The findings revealed a significant association between patient age (p < 0.001), body weight (p = 0.023), nationality (p = 0.015), educational level (p = 0.027), and the presence of comorbidities (p = 0.005) with the level of medication adherence. Conclusions: This study revealed that most diabetic patients attending PHCs in Madinah exhibited medium-to-high levels of medication adherence, with key influencing factors including age, comorbidities, education level, physician satisfaction, and health self-awareness.

1. Introduction

Diabetes mellitus is a chronic metabolic disease causing global health concern, as its incidence is continuously rising, specifically that of type 2 diabetes, which accounts for 90% of diabetes cases [1]. According to global, regional, and national diabetes prevalence estimates for 2024 and projections for 2050, published by the International Diabetes Federation’s Diabetes Atlas, 589 million adults (11.1%) were living with diabetes in 2024, and this number is projected to rise to 853 million by 2050 [2]. Additionally, the prevalence of diabetes will increase by 10.9% in 2045, with the number of cases possibly reaching 700 million [3]. In Saudi Arabia, the last ten years have seen a notable increase in diabetes cases of 8%, which is alarming because, at present, 25% of the Saudi population has diabetes [4]. Consequently, prevention and treatment strategies, including anti-diabetic therapies and lifestyle changes, are mandatory to control diabetes and lower the incidence of prediabetes [5]. In particular, adherence to insulin or oral medications has been proven to provide better health outcomes and patient satisfaction. Additionally, research has found that diabetes medication adherence reduces the risk of related complications, such as nephropathy, retinopathy, and foot complications, as well as hospitalization and mortality rates [6].

However, the current literature has revealed that one in every three diabetic patients does not adhere to the prescribed medication regimen [7]. Moreover, each 10% reduction in adherence is linked to a 0.14% increase in glycosylated hemoglobin (HbA1c), leading to serious complications and higher rates of emergency visits [8]. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), half of the population adheres to chronic disease medications in developed countries and less than half in underdeveloped countries. This results in higher mortality rates, thereby placing a financial burden on the patient and the healthcare system [9]. Although there is no standardized method for assessing medication adherence, the Morisky Medication Adherence Scale (MMAS) is a validated, reliable, and self-reported tool used for this purpose, and it could be beneficial for detecting the potential factors affecting such adherence [10].

Several studies have reported some of the cultural and socioeconomic factors that influence the medication adherence of diabetic patients. Researchers have observed that social support and self-efficacy play key roles in adherence [11,12]. Furthermore, financial and employment status have a strong association with the degree of adherence [13]. In addition, trust between the patient and the physician has a substantial effect on medication adherence, which could be achieved by proper communication and a better understanding of medication [14].

As medication adherence is a prerequisite for better health outcomes, besides lifestyle changes, a comprehensive understanding of the cultural beliefs and socioeconomic factors that could impact this adherence is important. This could benefit primary healthcare professionals in improving their quality of care and avoiding serious complications. Thus, this study aimed to assess the relationship between cultural and socioeconomic factors, patient preferences, and medication adherence among diabetic patients.

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design and Setting

This was a cross-sectional observational study that used face-to-face questionnaires and personal interviews. This study was conducted in 159 primary healthcare clinics (PHCs) in Madinah, Saudi Arabia, from 26 August 2024 to 10 February 2025.

2.2. Study Population

Data were collected from diabetic patients attending PHCs in Madinah City, Saudi Arabia.

2.2.1. Inclusion Criteria

A diverse group of patients with type 1 and type 2 diabetes was included, ensuring representation of various cultural and socioeconomic backgrounds.

2.2.2. Exclusion Criteria

The exclusion criteria were patients without diabetes, those with mental health or psychiatric conditions, and those who did not understand either English or Arabic.

2.2.3. Sampling Technique and Sample Size

A convenient sampling technique was used. The sample size was calculated using the Raosoft online sample size calculator. Considering a margin of error of 5%, a confidence level of 95%, and maximum uncertainty, a minimum of 377 participants was required, and this was rounded up to 400 to account for approximately 10% invalid or incomplete responses.

2.3. Data Collection Method and Tools

Data were collected using face-to-face questionnaires and personal interviews. The questionnaire included sociodemographic characteristics (gender, age, weight, height, smoking status, marital status, educational level, and health insurance coverage) and dependent variables, such as the patient’s beliefs towards diabetes mellitus, preferences regarding treatment modalities, dietary adjustments, lifestyle changes, confidence in disease management, understanding of medications, medication adherence behaviors, and challenges faced. Age was stratified into three groups (<40, 40–59, and ≥60 years) to reflect younger, middle-aged, and older adult life stages commonly used in epidemiological studies and to ensure adequate sample sizes for subgroup analyses. The Morisky Medication Adherence Scale-4 (MMAS-4), specifically adapted for diabetes medication adherence, was utilized. This scale comprises four items that assess various aspects of medication-taking behavior, including forgetting, carelessness, stopping medication when feeling better, and stopping medication when feeling worse. The term “modified” refers to its specific application and interpretation in the context of diabetes management, drawing on established factors relevant to adherence in this patient population, as identified in previous research. Participants were divided into two groups based on their adherence scores: 0 (high adherence) and 1 to 4 (medium or low adherence). In addition to the MMAS-4, the General Medication Adherence Scale (GMAS) was also employed; the use of both scales stemmed from their complementary strengths in assessing medication adherence. The MMAS-4, a widely validated and concise tool, allows for the quick screening of non-adherence behaviors, particularly identifying intentional and unintentional barriers. Conversely, the GMAS offers a more comprehensive and nuanced assessment of adherence across various behaviors, utilizing an 11-item Likert scale to capture a broader spectrum of adherence levels (e.g., high, good, partial, low, and poor). This dual approach allowed for a robust evaluation of adherence, with the MMAS-4 providing a rapid screening approach and the GMAS providing a more detailed, multi-faceted understanding, thereby enhancing the validity and reliability of our adherence measures. Following the administration of the quantitative questionnaire, a semi-structured qualitative interview was conducted with a subset of patients. These interviews aimed to gain deeper insights into the participants’ beliefs, perceptions, and experiences related to diabetes self-management, treatment adherence challenges, and facilitators. Key areas explored included personal understanding of their condition, barriers to healthy lifestyle choices, motivations for adherence, and interactions with healthcare providers. During these interviews, recent HbA1c values were extracted from participants’ electronic laboratory records for tests conducted within the three months prior to questionnaire administration to assess diabetes control. The qualitative interview data were collected and will be analyzed and reported in a separate, dedicated qualitative study to allow for a comprehensive exploration of the rich thematic insights into patient experiences.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

IBM Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) software, version 26.0, was used for data analyses. A descriptive analysis was performed to describe categorical data using numbers and proportions. For numerical data, the median and interquartile range (IQR) were used for non-normally distributed data after conducting the Shapiro–Wilk test. Associations between categorical variables were assessed using Pearson’s chi-square test. The Mann–Whitney and Kruskal–Wallis tests were used to assess the relationship between cultural and socioeconomic factors and the participants’ adherence to medication. A p < 0.05 was used to determine statistical significance.

The Morisky Medication Adherence Scale (MMAS-4) was utilized to assess the level of adherence to diabetes medication. Respondents who answer “no”, indicating the patient did not exhibit the non-adherent behavior, receive a score of 0, while those who answer “yes” receive a score of 1. The scores of the individual items are summed to categorize adherence as high (0), medium (1–2), or low (3–4). For our analyses, we then dichotomized these categories into high adherence (score = 0) versus medium/low adherence (score ≥ 1). The General Medication Adherence Scale (GMAS) is a self-reporting tool consisting of 11 items. Each item is scored using a 4-point Likert scale: “Always” scores 0, “Mostly” scores 1, “Sometimes” scores 2, and “Never” scores 3. Respondents receive a score based on their adherence level, with a maximum possible score of 33. To obtain the final score, the scores of all items are added together, allowing for an assessment of adherence categorized as follows: high (30–33), good (27–29), partial (17–26), low (11–16), or poor (10 or below).

2.5. Ethical Considerations

The Institutional Review Board (IRB) of the General Directorate of Health Affairs in Madinah granted approval for this research under ethical ID 24-078 on 18 August 2024. The committee is registered with the National Registration Number NCBE-KACST, KSA (H-03-M-84). Permission to use the MMAS-4 was granted by its developer, Dr. Donald E. Morisky. This scale is copyrighted (U.S. Reg. No. TX-8-285-390) and is licensed under Certificate Number 0942-6773-4869-8100-6082, issued on 20 May 2025. Proper attribution and usage were adhered to according to the terms outlined at www.adherence.cc (accessed on 25 July 2025). All procedures followed relevant guidelines and regulations, including the Declaration of Helsinki. Written informed consent was obtained from the participants. All information provided by the study participants was kept confidential and anonymous.

3. Results

This study included 424 diabetic patients from PHCs in Madinah City, Saudi Arabia. The participants were mostly middle-aged (40–59 years), Saudi Arabian, and female, and the majority had a university education, were unemployed, and lacked health insurance coverage. Most participants were non-smokers and reported receiving help with their diabetes care. All details are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Participants’ demographic characteristics (N = 424).

Regarding clinical and medication profiles, type 2 diabetes was predominant among the participants. More than half of the patients did not have diabetes-related complications, but the majority had uncontrolled diabetes, with HbA1c above 6.5%. Most patients primarily used oral diabetes medications, did not rely on herbal medications, and reported receiving diabetes education and regular doctor visits. All clinical details are available in Table 2.

Table 2.

Participants’ clinical and diabetes medication profiles (N = 424).

The patients’ beliefs towards diabetes mellitus varied, with a high proportion disagreeing that diabetes only occurs with high blood sugar levels, has low consequences, or has minimal symptoms. Conversely, the majority agreed that diabetes interferes with their social life, that diabetes medication could lead to addiction, and that they had low control over their diabetes. Table 3 provides a comprehensive overview of the participants’ beliefs.

Table 3.

Participants’ beliefs towards diabetes mellitus (N = 424).

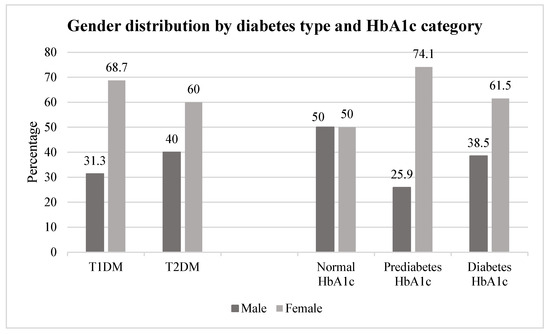

Figure 1 illustrates the gender distribution across diabetes type and HbA1c categories. Among participants with type 1 diabetes, 31.3% were male, and 68.7% were female; for type 2 diabetes, 40.0% were male, and 60.0% were female. Normal HbA1c was 50.0% in males versus 50.0% in females, prediabetes HbA1c was 25.9% in males versus 74.1% in females, and diabetes HbA1c was 38.5% in males versus 61.5% in females. Chi-square tests showed no significant differences by gender for diabetes type (p = 0.087) or HbA1c category (p = 0.124).

Figure 1.

Gender distribution by diabetes type and HbA1c category (N = 424). HbA1c categories: normal < 5.7%; prediabetes 5.7–6.4%; diabetes ≥ 6.5%.

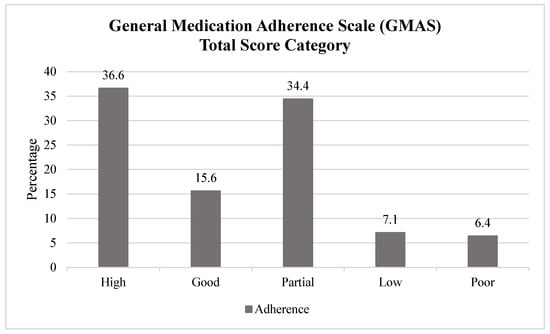

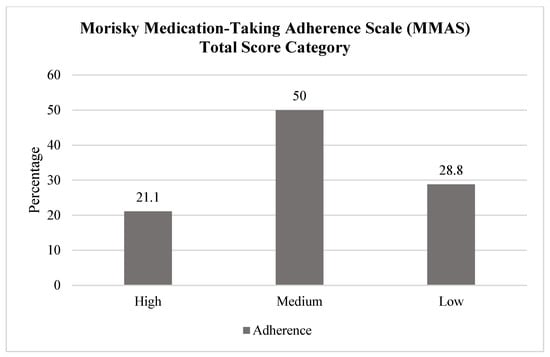

Regarding medication adherence levels, Figure 2 illustrates the distribution of adherence categories based on the GMAS. A notable proportion of the participants, specifically 36.6%, demonstrated high medication adherence according to the GMAS. This suggests a moderate level of overall adherence within the study population. Similarly, Figure 3 presents the medication adherence distribution, as measured using the MMAS, revealing that half of the diabetic patients (50%) exhibited medium adherence.

Figure 2.

General Medication Adherence Scale (GMAS)—total score category (N = 424). GMAS categories: high (30–33), good (27–29), partial (17–26), low (11–16), or poor (10 or below).

Figure 3.

Morisky Medication-Taking Adherence Scale (MMAS)—total score category (N = 424). MMAS categories: high (0), good (27–29), medium (1–2), or low (3–4).

A significant association was found between higher adherence and older age (p < 0.001; p = 0.004), being overweight (p = 0.023), Saudi nationality (p = 0.015), and holding a higher education level (p = 0.027). Additionally, the presence of comorbidities (p = 0.005), taking five or more medications (p < 0.001), having type 2 diabetes (p = 0.024), and a diabetes duration of more than 10 years (p = 0.002) were associated with higher adherence levels. More significant results are presented in Table 4.

Table 4.

Impact of diabetic patients’ sociodemographic and clinical characteristics on medication adherence (N = 242).

Regarding beliefs, adherence was significantly higher among those who were satisfied with their physician (p = 0.008) and those who disagreed with negative beliefs (e.g., fear of addiction and side effects, low diabetes control and confidence in management, lack of symptoms, and not needing medications with normal blood sugar) (p < 0.001). The patients who disagreed with specific misconceptions about diabetes (e.g., diabetes occurring only with high blood sugar levels or having low consequences) showed significantly higher adherence on the GMAS (p = 0.022 and p = 0.01, respectively). All results are presented in Table 5.

Table 5.

Impact of diabetic patients’ beliefs on medication adherence (N = 242).

4. Discussion

Patient adherence to medications prescribed for chronic illnesses such as diabetes mellitus is an essential factor for successfully achieving good glycemic control and proper management of the disease. However, some patients find it difficult to adhere to their medication, especially if its duration is lifelong. Research has shown that about 59.8% of type 2 diabetic patients have poor medication adherence [15], which can be attributed to various influencing factors. This study aimed to evaluate the relationship between cultural and socioeconomic factors, patient preferences, and medication adherence among diabetic patients.

This study revealed that medication adherence among diabetic patients in Madinah was generally moderate. Notably, we found that older age, higher education, and a longer diabetes duration were positively associated with higher adherence. This aligns with the observations of Shaha et al. [16], who also noted that elderly patients with higher secondary education and those with more than 10 years of diabetes were more adherent. While Shaha et al. also reported higher compliance among urban and employed patients, we did not observe significance regarding employment status or residential area, likely because almost half of our population was unemployed, and most resided in urban areas. These results indicate that accumulated self-management skills and improved health literacy, often gained through sustained experience with the disease, contribute to better adherence over time.

Interestingly, patients with comorbidities and those prescribed multiple medications both demonstrated higher adherence, suggesting heightened disease awareness, increased motivation to manage health, and enhanced engagement with healthcare providers that fosters routine medication-taking behaviors. These integrated findings align with a Tanzanian study [17] and Gast et al. [13], despite contrasting results reported by Al-Noumani et al. [14], and underscore the positive influence of self-efficacy, provider support, and confidence in disease management on adherence in chronic conditions [18,19,20].

A notable finding was the strong influence of physician satisfaction on adherence, echoing the literature emphasizing the role of trust and communication in chronic disease management. Patients who felt supported by their doctors were more likely to adhere to their treatment, underscoring the need for patient-centered communication strategies. This aligns with another Saudi study conducted by Khan et al. in Al-Hasa district [21]. This positive influence could be attributed to successful patient–physician communication, characterized by support, simplified essential information, and active listening, which subsequently fosters a regular follow-up routine.

Furthermore, beliefs and perceptions significantly impacted adherence. Patients who rejected misconceptions, such as viewing diabetes medications as addictive or only necessary when blood sugar is high, were consistently more adherent. This highlights the importance of targeted education to dispel myths and reinforce the chronic nature of diabetes.

This study could shed light on the importance of improving patient education regarding the management of type 2 diabetes. Primary healthcare providers can target the factors leading to non-adherent behavior to avoid patient complications and reduce hospitalization rates and mortality.

Future Perspectives

Although our findings add to the growing body of literature on diabetes care in the Middle East, future research should explore additional cultural factors prevalent in this region, such as the dynamics of family involvement in patient care and healthcare expectations, as these may profoundly influence medication adherence behaviors and provide further insights.

5. Limitations

Our study has several limitations, including its cross-sectional nature, which could lead to recall and social desirability biases, thereby limiting the establishment of causal relationships between the variables. Not all factors were assessed, such as the availability and cost of medications. Additionally, this study employed a cross-sectional design with convenience sampling techniques, which may limit the generalizability of the findings, as cultural beliefs can vary significantly from one population to another. Future studies should preferably employ a prospective longitudinal design with more confounding variables for more precise findings.

6. Conclusions

In conclusion, medication adherence among diabetic patients in Madinah was generally moderate. According to the MMAS-4, 50% of participants exhibited medium adherence, with 28.8% classified as high adherers and 21.1% classified as low adherers. According to the GMAS, 36.6% demonstrated high adherence, and 34.4% demonstrated good adherence. Additionally, this study identified possible influencing factors, including patient characteristics such as age, the presence of comorbidities, educational level, patient satisfaction with their physicians, and health self-awareness. Healthcare providers and policymakers should collaborate to implement health educational campaigns to raise awareness of diabetes medication adherence and self-management to achieve better clinical outcomes in diabetic patients.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.A.; Methodology, A.A. (Asrar Alharbi), S.A., R.A.H., T.A., E.A., A.A. (Afrah Aljabri) and N.S.A.; Formal analysis, M.A.; Data curation, A.A. (Asrar Alharbi), S.A., R.A.H., T.A., E.A. and A.A. (Afrah Aljabri); Writing—original draft preparation, A.A. (Asrar Alharbi), S.A., R.A.H., T.A., E.A., A.A. (Afrah Aljabri) and N.S.A.; Writing—review and editing, M.A. and N.S.A.; Supervision, M.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This scientific paper is derived from a research grant funded by Taibah University, Madinah, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, with grant number (447-13-999).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The Institutional Review Board (IRB) of the General Directorate of Health Affairs in Madinah granted approval for this research under ethical ID 24-078 on 18 August 2024.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express their sincere gratitude to Taibah University, Madinah, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, for supporting this research through grant number (447-13-999).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Chatterjee, S.; Khunti, K.; Davies, M.J. Type 2 diabetes. Lancet 2017, 389, 2239–2251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Genitsaridi, I.; Salpea, P.; Salim, A.; Sajjadi, S.F.; Tomic, D.; James, S.; Thirunavukkarasu, S.; Issaka, A.; Chen, L.; Basit, A.; et al. International Diabetes Federation Diabetes Atlas: Global, regional and national diabetes prevalence estimates for 2024 and projections for 2050. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2025. preprint. [Google Scholar]

- Saeedi, P.; Petersohn, I.; Salpea, P.; Malanda, B.; Karuranga, S.; Unwin, N.; Colagiuri, S.; Guariguata, L.; Motala, A.A.; Ogurtsova, K.; et al. Global and regional diabetes prevalence estimates for 2019 and projections for 2030 and 2045: Results from the International Diabetes Federation Diabetes Atlas. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2019, 157, 107843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Khaldi, Y.M.; Khan, M.Y.; Khairallah, S.H. Audit of referral of diabetic patients. Saudi Med. J. 2002, 23, 177–181. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Jia, W.; Weng, J.; Zhu, D.; Ji, L.; Lu, J.; Zhou, Z.; Zou, D.; Guo, L.; Ji, Q.; Chen, L.; et al. Standards of medical care for type 2 diabetes in China 2019. Diabetes/Metab. Res. Rev. 2019, 35, e3158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aikens, J.E.; Piette, J.D. Longitudinal association between medication adherence and glycaemic control in type 2 diabetes. Diabet. Med. 2013, 30, 338–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kirkman, M.S.; Rowan-Martin, M.T.; Levin, R.; Fonseca, V.A.; Schmittdiel, J.A.; Herman, W.H.; Aubert, R.E. Determinants of adherence to diabetes medications: Findings from a large pharmacy claims database. Diabetes Care 2015, 38, 604–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pladevall, M.; Williams, L.K.; Potts, L.A.; Divine, G.; Xi, H.; Lafata, J.E. Clinical outcomes and adherence to medications by claims data in patients with diabetes. Diabetes Care 2004, 27, 2800–2805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alqarni, A.M.; Alrahbeni, T.; Qarni, A.A.; Qarni, H.M. Adherence to diabetes medication among diabetic patients in the Bisha governorate of Saudi Arabia—A cross-sectional survey. Patient Prefer. Adherence 2018, 13, 63–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laghousi, D.; Rezaie, F.; Alizadeh, M.; Jafarabadi, M.A. The eight-item Morisky Medication Adherence Scale: Validation of its Persian version in diabetic adults. Casp. J. Intern. Med. 2021, 12, 77. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, J.; Ding, S.; Xiong, S.; Liu, Z. Medication adherence and associated factors in patients with type 2 diabetes: A structural equation model. Front. Public Health 2021, 9, 730845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McQuaid, E.L.; Landier, W. Cultural issues in medication adherence: Disparities and directions. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2018, 33, 200–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gast, A.; Mathes, T. Medication adherence influencing factors—An (updated) overview of systematic reviews. Syst. Rev. 2019, 8, 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Noumani, H.; Alharrasi, M.; Lazarus, E.R.; Panchatcharam, S.M. Factors predicting medication adherence among Omani patients with chronic diseases through a multicenter cross-sectional study. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 7067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Z.P.; Premikha, M.; Luo, M.; Venkataraman, K. Diabetes distress and peripheral neuropathy are associated with medication non-adherence in individuals with type 2 diabetes in primary care. Acta Diabetol. 2021, 58, 309–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaha, K.C.; Sultana, S.; Saha, S.K.; Shahidullah, S.M.; Jyoti, B.K. Patient Characteristics Associated with Medication Adherence to Anti-Diabetic Drugs. Mymensingh Med. J. MMJ 2019, 28, 423–428. [Google Scholar]

- Rwegerera, G.M. Adherence to anti-diabetic drugs among patients with Type 2 diabetes mellitus at Muhimbili National Hospital, Dar es Salaam, Tanzania—A cross-sectional study. Pan Afr. Med. J. 2014, 17, 252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, N.S.; Ramli, A.; Islahudin, F.; Paraidathathu, T. Medication adherence in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus treated at primary health clinics in Malaysia. Patient Prefer. Adherence 2013, 7, 525–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitiku, Y.; Belayneh, A.; Tegegne, B.A.; Kebede, B.; Abebe, D.; Biyazin, Y.; Bahiru, B.; Abebaw, A.; Mengist, H.M.; Getachew, M. Prevalence of medication non-adherence and associated factors among diabetic patients in a tertiary hospital at Debre Markos, Northwest Ethiopia. Ethiop. J. Health Sci. 2022, 32, 755–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Tian, Y.; Yin, M.; Lin, W.; Tuersun, Y.; Li, L.; Yang, J.; Wu, F.; Kan, Y.; Li, X.; et al. Relationship between self-efficacy and adherence to self-management and medication among patients with chronic diseases in China: A multicentre cross-sectional study. J. Psychosom. Res. 2023, 164, 111105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.R.; Lateef, Z.N.; Al Aithan, M.A.; Bu-Khamseen, M.A.; Al Ibrahim, I.; Khan, S.A. Factors contributing to non-compliance among diabetics attending primary health centers in the Al Hasa district of Saudi Arabia. J. Fam. Community Med. 2012, 19, 26–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).