Evaluation of a Theoretical and Experiential Training Programme for Allied Healthcare Providers to Prescribe Exercise Among Persons with Multiple Sclerosis: A Co-Designed Effectiveness-Implementation Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

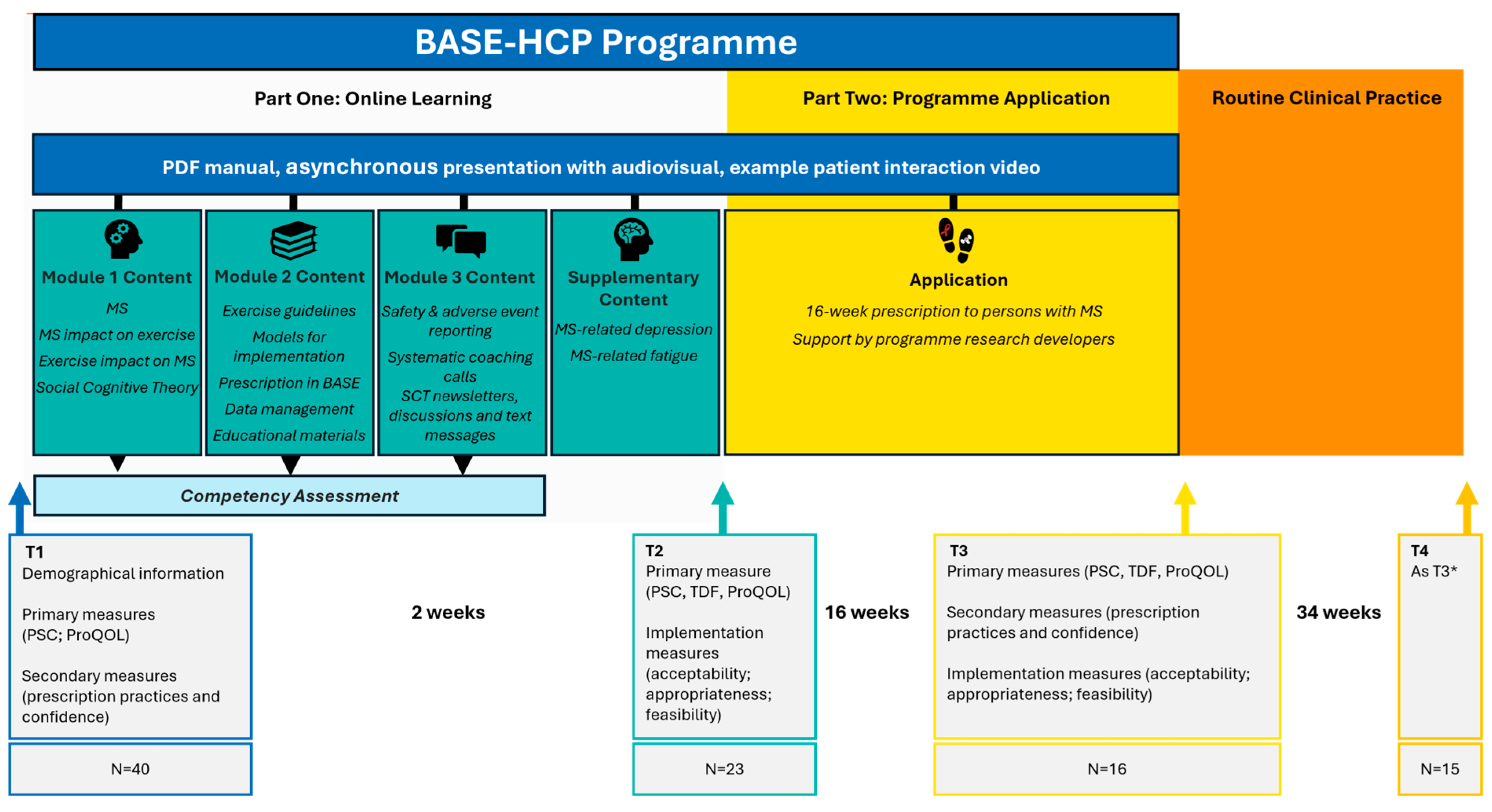

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Context

2.3. Participant Inclusion Criteria

2.4. Outcome Measures

2.4.1. Primary Outcome Measures

2.4.2. Secondary Outcome Measures

2.4.3. Implementation Evaluation Outcomes

2.5. BASE-HCP Programme

2.5.1. Online Learning

2.5.2. Programme Application

2.6. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Participant Recruitment and Characteristics

3.2. Participant Preferences for Education on Remote Exercise Delivery

3.3. Intervention Effect

3.3.1. Primary Outcomes

Practitioner Self-Confidence (PSC)

Theoretical Domains Framework (TDF)

Professional Quality of Life (ProQOL)

Significant Predictors

3.3.2. Secondary Outcomes

Changes in Remote Exercise Prescription Practices and Confidence

Post-Training Practice Changes and Knowledge Application

3.4. BASE Implementation Evaluation

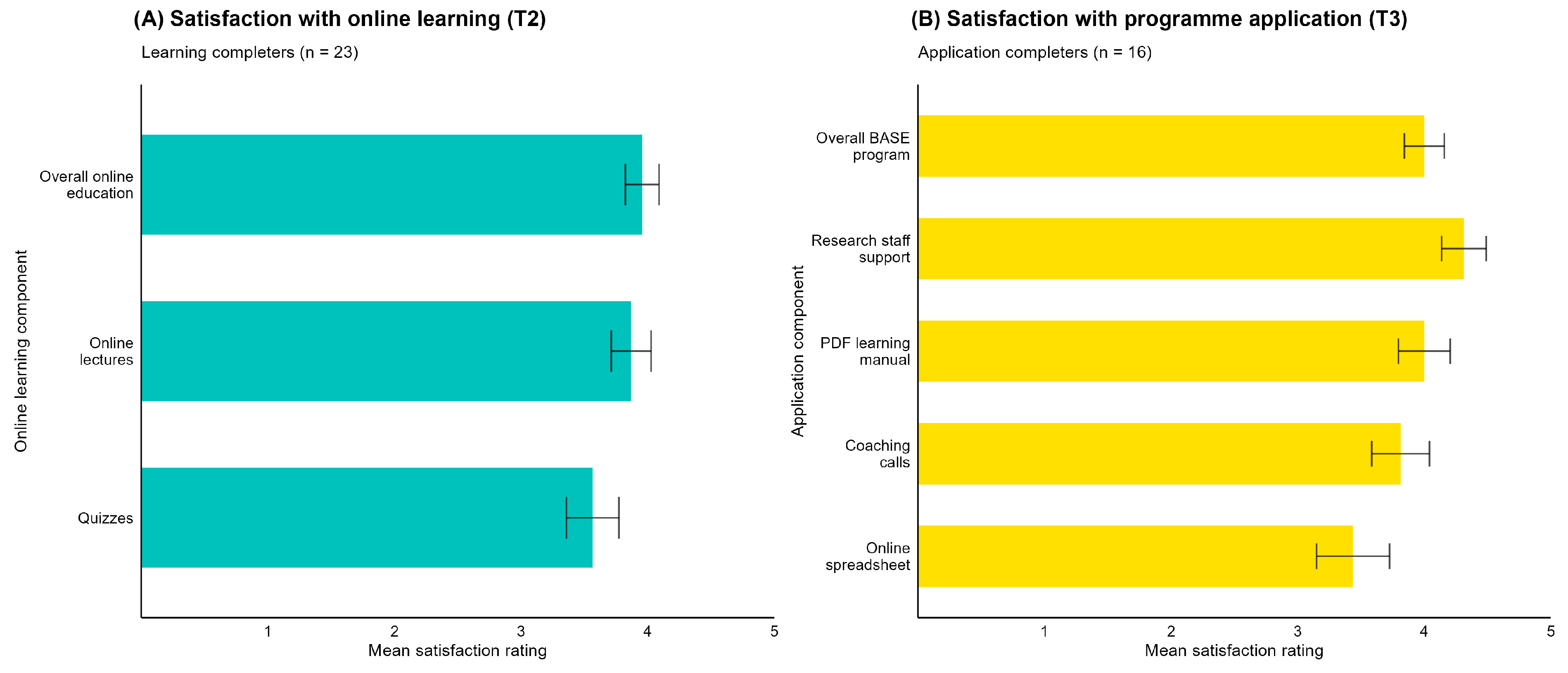

3.4.1. Acceptability of the BASE-HCP Programme

3.4.2. Appropriateness of the BASE-HCP Programme

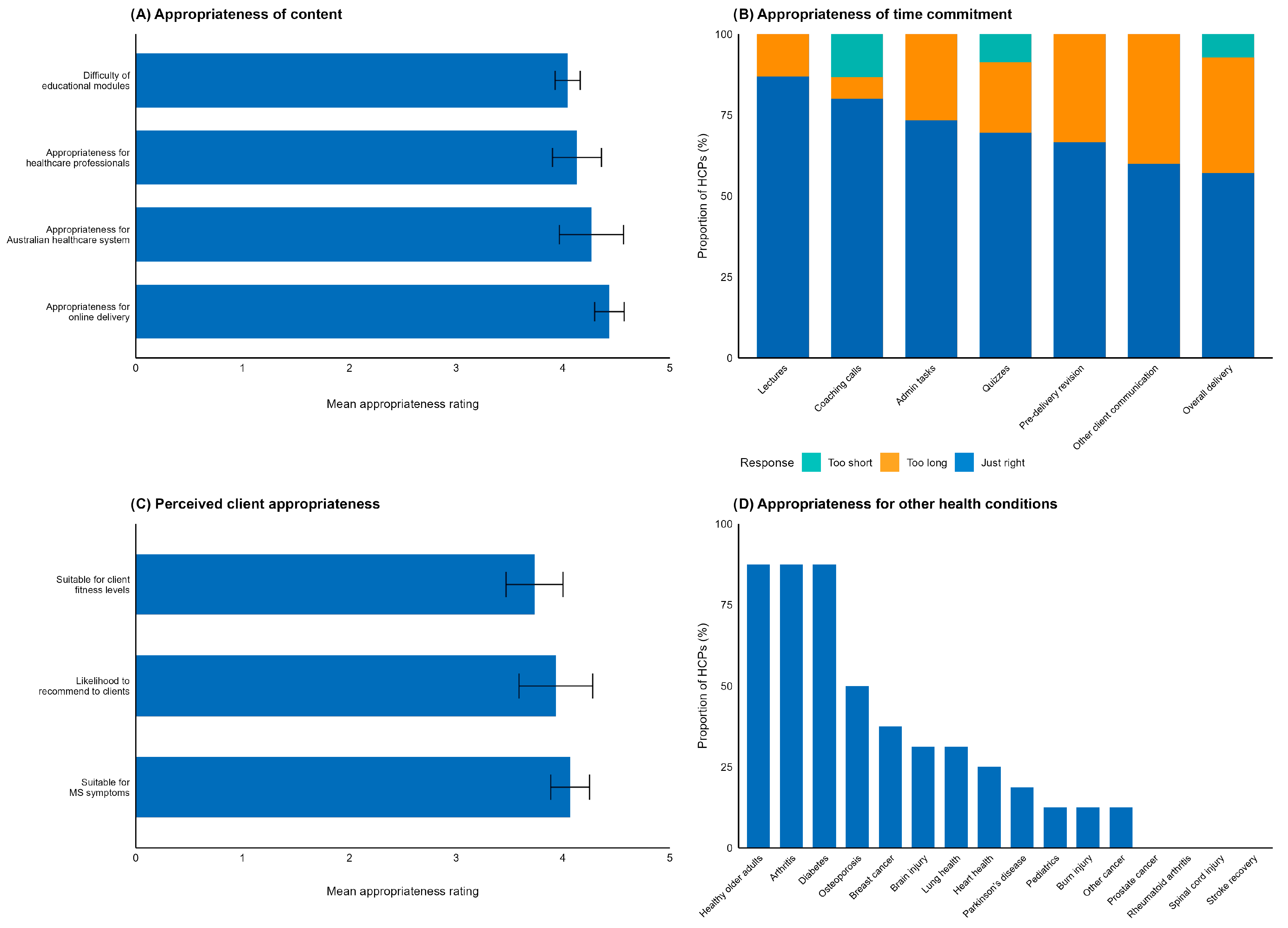

Appropriateness of Content and Time Commitment

Perceived Client Appropriateness

Perceived Client Outcomes

Appropriateness for Application to Other Health Conditions

Appropriateness for Professional Delivery

Suggested Adaptations for BASE-HCP Implementation

Suggested Adaptations for Scaling to Other Health Conditions

3.4.3. Feasibility of the BASE-HCP Programme

Participant Attrition

Feasibility of Time Commitment

Barriers to Implementation in Routine Clinical Practice

4. Discussion

Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| MS | Multiple Sclerosis |

| HCP | Healthcare professionals |

| BASE-HCP | Education Programme for healthcare professionals, Changing Behaviour towards aerobic and Strength Exercise |

| PSC | Practitioner Self-confidence Scale |

| SCT | Social Cognitive Theory |

| ProQOL | Professional Quality of Life Scale |

| TDF | Theoretical Domains Framework |

| T1 | Baseline data collection |

| T2 | Post-theoretical online learning data collection |

| T3 | Post-experiential/programme application data collection |

| T4 | Six to eight months post learning data collection |

| COVID-19 | Coronavirus pandemic 2020–2023 |

| BASE-HCP | Changing Behaviour towards Aerobic and Strength Exercise Programmes delivered to persons with MS |

References

- King, R. PART 1: Mapping Multiple Sclerosis Around the World Key Epidemiology Findings. In Atlas of MS, 3rd ed.; Multiple Sclerosis International Federation: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell, J.A.; Simpson, S.; Ahmad, H.; Taylor, B.V.; van der Mei, I.; Palmer, A.J. Change in multiple sclerosis prevalence over time in Australia 2010–2017 utilising disease-modifying therapy prescription data. Mult. Scler. J. 2019, 26, 1315–1328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalgas, U.; Langeskov-Christensen, M.; Stenager, E.; Riemenschneider, M.; Hvid, L.G. Exercise as medicine in multiple sclerosis-time for a paradigm shift: Preventive, symptomatic, and disease-modifying aspects and perspectives. Curr. Neurol. Neurosci. Rep. 2019, 19, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Learmonth, Y.C.; Motl, R.W. Exercise training for multiple sclerosis: A narrative review of history, benefits, safety, guidelines, and promotion. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 13245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marck, C.; Learmonth, Y.C.; Chen, J.; van der Mei, I. Physical activity, sitting time and exercise types, and associations with symptoms in Australian people with multiple sclerosis. Disabil. Rehabil. 2022, 44, 1380–1388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latimer-Cheung, A.E.; Pilutti, L.A.; Hicks, A.L.; Martin Ginis, K.A.; Fenuta, A.; Mackibbon, K.A.; Motl, R.W. The effects of exercise training on fitness, mobility, fatigue, and health related quality of life among adults with multiple sclerosis: A systematic review to inform guideline development. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2013, 94, 1800–1828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.; Lai, B.; Mehta, T.; Thirumalai, M.; Padalabalanarayanan, S.; Rimmer, J.H.; Motl, R.W. Exercise training guidelines for multiple sclerosis, stroke, and parkinson disease: Rapid review and synthesis. Am. J. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2019, 98, 613–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalb, R.; Brown, T.R.; Coote, S.; Costello, K.; Dalgas, U.; Garmon, E.; Giesser, B.; Halper, J.; Karpatkin, H.; Keller, J.; et al. Exercise and lifestyle physical activity recommendations for people with multiple sclerosis throughout the disease course. Mult. Scler. 2020, 26, 1459–1469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Learmonth, Y.C.; Adamson, B.C.; Balto, J.M.; Chiu, C.-Y.; Molina-Guzman, I.; Finlayson, M.; Riskin, B.J.; Motl, R.W. Multiple sclerosis patients need and want information on exercise promotion from healthcare providers: A qualitative study. Health Expect. 2017, 20, 574–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Learmonth, Y.C.; Adamson, B.C.; Balto, J.M.; Chiu, C.-Y.; Molina-Guzman, I.M.; Finlayson, M.; Barstow, E.A.; Motl, R.W. Investigating the needs and wants of healthcare providers for promoting exercise in persons with multiple sclerosis: A qualitative study. Disabil. Rehabil. 2018, 40, 2172–2180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mavropalias, G.; Baynton, S.L.; Teo, S.; Donkers, S.J.; Van Rens, F.E.; Learmonth, Y.C. Allied health professionals knowledge and clinical practice in telehealth exercise behavioural change for multiple sclerosis. Mult. Scler. Relat. Disord. 2024, 87, 105689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barton, C.J.; King, M.G.; Dascombe, B.; Taylor, N.F.; de Oliveira Silva, D.; Holden, S.; Goff, A.J.; Takarangi, K.; Shields, N. Many physiotherapists lack preparedness to prescribe physical activity and exercise to people with musculoskeletal pain: A multi-national survey. Phys. Ther. Sport 2021, 49, 98–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Learmonth, Y.C.; Adamson, B.C.; Kinnett-Hopkins, D.; Bohri, M.; Motl, R.W. Results of a feasibility randomised controlled study of the guidelines for exercise in multiple sclerosis project. Contemp. Clin. Trials 2017, 54, 84–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tarakci, E.; Tarakci, D.; Hajebrahimi, F.; Budak, M. Supervised exercises versus telerehabilitation. Benefits for persons with multiple sclerosis. Acta Neurol. Scand. 2021, 144, 303–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, Y.; Mehta, T.; Tracy, T.; Young, H.-J.; Pekmezi, D.W.; Rimmer, J.H.; Niranjan, S.J. A qualitative evaluation of a clinic versus home exercise rehabilitation program for adults with multiple sclerosis: The tele-exercise and multiple sclerosis (TEAMS) study. Disabil. Health J. 2023, 16, 101437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garg, H.; Rutherfurd, C.; Labrum, J.; Hawley, B.; Gard, E.; Davis, J. Feasibility, Outcomes, and Perceptions of a Virtual Group Exercise Program in Multiple Sclerosis. J. Neurol. Phys. Ther. 2024, 48, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motl, R.W.; Barstow, E.A.; Blaylock, S.; Richardson, E.; Learmonth, Y.C.; Fifolt, M. Promotion of exercise in multiple sclerosis through health care providers. Exerc. Sport Sci. Rev. 2018, 46, 105–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leahy, E.; Chipchase, L.; Calo, M.; Blackstock, F.C. Which Learning Activities Enhance Physical Therapist Practice? Part 2: Systematic Review of Qualitative Studies and Thematic Synthesis. Phys. Ther. 2020, 100, 1484–1501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leahy, E.; Chipchase, L.; Calo, M.; Blackstock, F.C. Which Learning Activities Enhance Physical Therapist Practice? Part 1: Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of Quantitative Studies. Phys. Ther. 2020, 100, 1469–1483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Normann, B.; Sørgaard, K.W.; Salvesen, R.; Moe, S. Clinical guidance of community physiotherapists regarding people with MS: Professional development and continuity of care. Physiother. Res. Int. 2014, 19, 25–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munneke, M.; Nijkrake, M.J.; Keus, S.H.; Kwakkel, G.; Berendse, H.W.; Roos, R.A.; Borm, G.F.; Adang, E.M.; Overeem, S.; Bloem, B.R. Efficacy of community-based physiotherapy networks for patients with Parkinson’s disease: A cluster-randomised trial. Lancet Neurol. 2010, 9, 46–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Peppen, R.P.S.; Schuurmans, M.J.; Stutterheim, E.C.; Lindeman, E.; Van Meeteren, N.L.U. Promoting the use of outcome measures by an educational programme for physiotherapists in stroke rehabilitation: A pilot randomized controlled trial. Clin. Rehabil. 2009, 23, 1005–1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almohiza, M.A.; Sparto, P.J.; Marchetti, G.F.; Delitto, A.; Furman, J.M.; Miller, D.L.; Whitney, S.L. A Quality Improvement Project in Balance and Vestibular Rehabilitation and Its Effect on Clinical Outcomes. J. Neurol. Phys. Ther. 2016, 40, 90–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jolliffe, L.; Hoffmann, T.; Churilov, L.; Lannin, N.A. What is the feasibility and observed effect of two implementation packages for stroke rehabilitation therapists implementing upper limb guidelines? A cluster controlled feasibility study. BMJ Open Qual. 2020, 9, e000954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Learmonth, Y.C.; Kaur, I.; Baynton, S.L.; Fairchild, T.; Paul, L.; van Rens, F. Changing behaviour towards aerobic and strength exercise (BASE): Design of a randomised, phase I study determining the safety, feasibility and consumer-evaluation of a remotely-delivered exercise programme in persons with multiple sclerosis. Contemp. Clin. Trials 2021, 102, 106281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morris, T.H. Self-directed learning: A fundamental competence in a rapidly changing world. Int. Rev. Educ. 2019, 65, 633–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, T.H. Experiential learning—A systematic review and revision of Kolb’s model. Interact. Learn. Environ. 2020, 28, 1064–1077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, I.; Baynton, S.L.; White-Kielly, A.; Paul, L.; Wall, B.; van Rens, F.; Fairchild, T.; Learmonth, Y. Implementing Changing Behaviour towards Aerobic and Strength Exercise: Results of a randomised, phase I study determining the safety, feasibility, and consumer evaluation of an online exercise program in persons with multiple sclerosis. Contemp. Clin. Trials 2024, 146, 107686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pinnock, H.; Barwick, M.; Carpenter, C.R.; Eldridge, S.; Grandes, G.; Griffiths, C.J.; Rycroft-Malone, J.; Meissner, P.; Murray, E.; Patel, A.; et al. Standards for Reporting Implementation Studies (StaRI) Statement. BMJ 2017, 356, i6795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Proctor, E.; Silmere, H.; Raghavan, R.; Hovmand, P.; Aarons, G.; Bunger, A.; Griffey, R.; Hensley, M. Outcomes for Implementation Research: Conceptual Distinctions, Measurement Challenges, and Research Agenda. Adm. Policy Ment. Health 2011, 38, 65–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Australian Government Department of Health and Aged Care. Universal Telehealth Extended Through 2021. 2021. Available online: https://www.health.gov.au/ministers/the-hon-greg-hunt-mp/media/universal-telehealth-extended-through-2021 (accessed on 4 September 2024).

- Smucker, D.R.; Konrad, T.R.; Curtis, P.; Carey, T.S. Practitioner self-confidence and patient outcomes in acute low back pain. Arch. Fam. Med. 1998, 7, 223–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huijg, J.M.; Gebhardt, W.A.; Crone, M.R.; Dusseldorp, E.; Presseau, J. Discriminant content validity of a theoretical domains framework questionnaire for use in implementation research. Implement. Sci. 2014, 9, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stamm, B. The Concise ProQOL Manual; Professional Quality of Life: Pocatello, ID, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Pawson, R.; Greenhalgh, T.; Harvey, G.; Walshe, K. Realist review—A new method of systematic review designed for complex policy interventions. J. Health Serv. Res. Policy 2005, 10, 21–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hohol, M.J.; Orav, E.J.; Weiner, H.L. Disease Steps in multiple sclerosis A simple approach to evaluate disease progression. Neurology 1995, 45, 251–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. Health promotion by social cognitive means. Health Educ. Behav. 2004, 31, 143–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Templ, M.; Alfons, A.; Kowarik, A.; Prantner, B. VIM: Visualization and Imputation of Missing Values; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Tierney, N.; Cook, D. Expanding Tidy Data Principles to Facilitate Missing Data Exploration, Visualization and Assessment of Imputations. J. Stat. Softw. 2023, 105, 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Audigier, V.; Resche-Rigon, M.; Munoz Avila, J. micemd: Multiple Imputation by Chained Equations with Multilevel Data (R Package Version 1.10.0). CRAN. 2023. Available online: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=micemd (accessed on 8 September 2025).

- Little, R.J.A. A Test of Missing Completely at Random for Multivariate Data with Missing Values. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 1988, 83, 1198–1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooks, M.E.; Kristensen, K.; van Benthem, K.J.; Magnusson, A.; Berg, C.W.; Nielsen, A.; Skaug, H.J.; Mächler, M.; Bolker, B.M. glmmTMB Balances Speed and Flexibility Among Packages for Zero-inflated Generalized Linear Mixed Modeling. R J. 2017, 9, 378–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunger, M.; Döring, A.; Holle, R. Longitudinal beta regression models for analyzing health-related quality of life scores over time. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2012, 12, 144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X. Multiple Imputation by Chained Equations with Multilevel Data; National Institutes of Health: Bethesda, MD, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Buuren, S.V.; Groothuis-Oudshoorn, K. Mice: Multivariate Imputation by Chained Equations in R. J. Stat. Softw. 2011, 45, 1–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robitzsch, A.; Grund, S.; Henke, T. Miceadds: Some Additional Multiple Imputation Functions, Especially for “Mice”, version 3.17-44; CRAN: Vienna, Austria, 2024.

- van Buuren, S. Multiple Imputations. In Flexible Imputation of Missing Data, 2nd ed.; Taylor and Francis Group: Abingdon, UK, 2018; pp. 29–62. [Google Scholar]

- Rubin, D. Underlying Bayesian Theory. In Multiple Imputation for Nonresponse in Surveys; Wiley: Chicester, UK, 1987; pp. 75–112. [Google Scholar]

- Lumley, T. R Package, version 2.4. mitools: Tools for Multiple Imputation of Missing Data. R-Universe: Auckland, New Zealand, 2019.

- Lenth, R.V.; Banfai, B.; Bolker, B.; Buerkner, P.; Giné-Vázquez, I.; Herve, M.; Jung, M.; Love, J.; Miguez, F.; Piaskowski, J.; et al. emmeans: Estimated Marginal Means, aka Least-Squares Means, version 1.11.2-8; RStudio: Vienna, Austria, 2025.

- Hartig, F.; Lohse, L.; Leite, M.d.S. DHARMa: Residual Diagnostics for Hierarchical (Multi-Level/Mixed) Regression Models, R Package version 0.4.6; RStudio: Vienna, Austria, 2024.

- Lüdecke, D.; Ben-Shachar, M.S.; Patil, I.; Waggoner, P.; Makowski, D. performance: An R Package for Assessment, Comparison and Testing of Statistical Models. J. Open Source Softw. 2021, 6, 3139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wickham, H.; Averick, M.; Bryan, J.; Chang, W.; McGowan, L.D.; François, R.; Grolemund, G.; Hayes, A.; Henry, L.; Hester, J.; et al. Welcome to the Tidyverse. J. Open Source Softw. 2019, 4, 1686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potthoff, S.; Kwasnicka, D.; Avery, L.; Finch, T.; Gardner, B.; Hankonen, N.; Johnston, D.; Johnston, M.; Kok, G.; Lally, P.; et al. Changing healthcare professionals’ non-reflective processes to improve the quality of care. Soc. Sci. Med. 2022, 298, 114840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motl, R.W.; Casey, B.; Learmonth, Y.C.; Latimer-Cheung, A.; Kinnett-Hopkins, D.L.; Marck, C.H.; Carl, J.; Pfeifer, K.; Riemann-Lorenz, K.; Heesen, C.; et al. The MoXFo initiative—Adherence: Exercise adherence, compliance and sustainability among people with multiple sclerosis: An overview and roadmap for research. Mult. Scler. 2023, 29, 1595–1603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sangelaji, B.; Nabavi, S.M.; Estebsari, F.; Banshi, M.R.; Rashidian, H.; Jamshidi, E.; Dastoorpour, M. Effect of combination exercise therapy on walking distance, postural balance, fatigue and quality of life in multiple sclerosis patients: A clinical trial study. Iran Red. Crescent Med. J. 2014, 16, e17173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malliaras, P.; Merolli, M.; Williams, C.; Caneiro, J.; Haines, T.; Barton, C. “It’s not hands-on therapy, so it’s very limited”: Telehealth use and views among allied health clinicians during the coronavirus pandemic. Musculoskelet. Sci. Pract. 2021, 52, 102340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marrie, R.A.; Kosowan, L.; Cutter, G.; Fox, R.; Salter, A. Disparities in Telehealth Care in Multiple Sclerosis. Neurol. Clin. Pract. 2022, 12, 223–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Learmonth, Y.C.; Galna, B.; Laslett, L.L.; van der Mei, I.; Marck, C.H. Improving telehealth for persons with multiple sclerosis—A cross-sectional study from the Australian MS longitudinal study. Disabil. Rehabil. 2024, 46, 4755–4762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ammentorp, J.; Chiswell, M.; Martin, P. Translating knowledge into practice for communication skills training for health care professionals. Patient Educ. Couns. 2022, 105, 3334–3338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Colquhoun, H.L.; Squires, J.E.; Kolehmainen, N.; Fraser, C.; Grimshaw, J.M. Methods for designing interventions to change healthcare professionals’ behaviour: A systematic review. Implement. Sci. 2017, 12, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Batchelor, J.; Hemmert, C.; Meulenbroeks, I.; Tang, C.; Harrison, R.; Ogrin, R.; Baillie, A.; Sarkies, M. Factors Influencing the Translation of Evidence into Clinical Practice for Hospital Allied Health Professionals in Terms of the Domains of Behaviour Change Theory: A Systematic Review. Eval. Health Prof. 2024, 01632787241285993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cunningham, F.C.; Morris, A.D.; Braithwaite, J. Experimenting with clinical networks: The Australasian experience. J. Health Organ. Manag. 2012, 26, 685–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guthrie, B.; Davies, H.; Greig, G.; Rushner, R.; Walter, I.; Duguid, A.; Coyle, J.; Sutton, M.; Williams, B.; Connaghan, J.; et al. Delivering Health Care Through Managed Clinical Networks (MCNs): Lessons from the North; Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO: Norwich, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Kitto, S.; Fantaye, A.W.; Ghidinelli, M.; Andenmatten, K.; Thorley Wiedler, J.; de Boer, K. Barriers and facilitators to the cultivation of communities of practice for faculty development in medical education: A scoping review. Med. Teach. 2025, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mather, M.; Pettigrew, L.M.; Navaratnam, S. Barriers and facilitators to clinical behaviour change by primary care practitioners: A theory-informed systematic review of reviews using the Theoretical Domains Framework and Behaviour Change Wheel. Syst. Rev. 2022, 11, 180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smidt, A.; Balandin, S.; Sigafoos, J.; Reed, V. The Kirkpatrick model: A useful tool for evaluating training outcomes. J. Intellect. Dev. Disabil. 2009, 34, 266–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Windfeld-Lund, C.; Sturt, R.; Pham, C.; Lannin, N.A.; Graco, M. Systematic Review of the Effectiveness of Allied Health Clinical Education Programs. J. Contin. Educ. Health Prof. 2023, 43, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beneciuk, J.M.; George, S.Z. Pragmatic Implementation of a Stratified Primary Care Model for Low Back Pain Management in Outpatient Physical Therapy Settings: Two-Phase, Sequential Preliminary Study. Phys. Ther. 2015, 95, 1120–1134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dizon, J.M.R.; Grimmer-Somers, K.; Kumar, S. Effectiveness of the tailored Evidence Based Practice training program for Filipino physical therapists: A randomized controlled trial. BMC Med. Educ. 2014, 14, 147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lonsdale, C.; Hall, A.M.; Murray, A.; Williams, G.C.; McDonough, S.M.; Ntoumanis, N.; Owen, K.; Schwarzer, R.; Parker, P.; Kolt, G.S.; et al. Communication Skills Training for Practitioners to Increase Patient Adherence to Home-Based Rehabilitation for Chronic Low Back Pain: Results of a Cluster Randomized Controlled Trial. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2017, 98, 1732–1743.e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subbarayalu, A.V. Development and validation of a tool for measuring the work-related quality of life of physical therapists. Int. J. Healthc. Manag. 2025, 18, 333–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pot, F. Workplace innovation and wellbeing at work. In Workplace Innovation: Theory, Research and Practice; Springer International Publishing: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2017; pp. 95–110. [Google Scholar]

- Bankhead, C.; Aronson, J.K.; Nunan, D. Attrition Bias|Catalog of Bias. 2017. Available online: https://catalogofbias.org/biases/attrition-bias/ (accessed on 6 June 2025).

- Hammond, A. What is the role of the occupational therapist? Best. Pract. Res. Clin. Rheumatol. 2004, 18, 491–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Collins, L.M.; Schafer, J.L.; Kam, C.M. A Comparison of Inclusive and Restrictive Strategies in Modern Missing Data Procedures. Psychol. Methods 2001, 6, 330–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faisal, S.; Tutz, G. Multiple Imputation Using Nearest Neighbor Methods. Inf. Sci. 2021, 570, 500–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaput-Langlois, S.; Stickley, Z.L.; Little, T.D.; Rioux, C. Multiple Imputation When Variables Exceed Observations: An Overview of Challenges and Solutions. Collabra Psychol. 2024, 10, 92993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubin, D. Multiple Imputation. In Flexible Imputation of Missing Data; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Little, R.J.A. Univariate Missing Data. In Flexible Imputation of Missing Data; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2018; pp. 63–103. [Google Scholar]

- Bennett, D.A. How Can I Deal with Missing Data in My Study? Aust. N. Z. J. Public Health 2001, 25, 464–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, J.W.; Olchowski, A.E.; Gilreath, T.D. How Many Imputations Are Really Needed? Some Practical Clarifications of Multiple Imputation Theory. Prev. Sci. 2007, 8, 206–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferrari, S.; Cribari-Neto, F. Beta Regression for Modelling Rates and Proportions. J. Appl. Stat. 2004, 31, 799–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burnham, K.; Anderson, D. Information and Likelihood Theory: A Basis for Model Selection and Inference. In Model Selection and Multimodel Inference: A Practical Information-Theoretic Approach; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2002; pp. 49–97. ISBN 978-0-387-95364-9. [Google Scholar]

- Rubin, D. Inference and Missing Data. Biometrika 1976, 63, 581–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, D.R. Regression Models and Life-Tables. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. B (Methodol.) 1972, 34, 187–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carpenter, J.R.; Kenward, M.G.; Vansteelandt, S. A Comparison of Multiple Imputation and Doubly Robust Estimation for Analyses with Missing Data. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. A (Stat. Soc.) 2006, 169, 571–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sterne, J.A.C.; White, I.R.; Carlin, J.B.; Spratt, M.; Royston, P.; Kenward, M.G.; Wood, A.M.; Carpenter, J.R. Multiple Imputation for Missing Data in Epidemiological and Clinical Research: Potential and Pitfalls. BMJ 2009, 338, b2393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristic | Result |

|---|---|

| Age | 35.4 ± 9.8 |

| Sex | |

| Female | 31 (77.5%) |

| Male | 9 (22.5%) |

| Region | |

| New South Wales | 5 (12.5%) |

| Queensland | 13 (32.5%) |

| South Australia | 1 (2.5%) |

| Tasmania | 0 (0.0%) |

| Victoria | 8 (20.0%) |

| Western Australia | 11 (27.5%) |

| Northern Territory | 1 (2.5%) |

| Australian Capital Territory | 1 (2.5%) |

| Clinical role | |

| Physiotherapist | 20 (50.0%) |

| Exercise physiologist Occupation Therapist | 20 (50.0%) 0 (0.0%) |

| Primary area of work | |

| Private clinic | 32 (80.0%) |

| Not for profit | 3 (7.5%) |

| State health authority | 2 (5.0%) |

| Other | 3 (7.5%) |

| Caseload, neurological | |

| 0% | 0 (0.0%) |

| 1–50% | 19 (47.5%) |

| 51–100% | 21 (52.5%) |

| Caseload, MS | |

| 0% | 5 (12.5%) |

| 1–50% | 31 (77.5%) |

| 51–100% | 4 (10.0%) |

| Aware of MS exercise guidelines? | |

| Yes | 27 (67.5%) |

| No | 13 (32.5%) |

| Formal training prepared participants to promote exercise to clients | |

| Strongly Agree | 22 (55.0%) |

| Agree | 13 (32.5%) |

| Neutral | 5 (12.5%) |

| Disagree | 0 (0.0%) |

| Strongly Disagree | 0 (0.0%) |

| Outcome Measure | T1 | T2 | T3 | T4 | Comparison | Result (β (SE), z, p) | Effect Size (HR (% Change) [95% CI]) | Direction of Change |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PSC_SC | 7.6 | 4.9 | 4.2 | 4.2 | T1 vs. T2 | 1.27 (0.24), 5.28, < 0.001 | 3.57 (+256.8%) [2.23, 5.72] | ↑ *** |

| (2.8) | (1.8) | (1.6) | (1.4) | T1 vs. T3 | 1.76 (0.25), 6.99, < 0.001 | 5.79 (+479.4%) [3.54, 9.48] | ↑ *** | |

| T1 vs. T4 | 1.75 (0.31), 5.67, < 0.001 | 5.74 (+474.1%) [3.14, 10.50] | ↑ *** | |||||

| T2 vs. T3 | 0.48 (0.31), 1.58, 0.11 | 1.62 (+62.4%) [0.89, 2.97] | ← → | |||||

| T2 vs. T4 | 0.48 (0.35), 1.37, 0.17 | 1.61 (+60.9%) [0.81, 3.18] | ← → | |||||

| T3 vs. T4 | <0.01 (0.30), −0.03, 0.98 | 0.99 (−0.9%) [0.55, 1.78] | ← → | |||||

| PSC_ATP | 5.3 | 6.1 | 5.6 | 5.6 | T1 vs. T2 | −0.41 (0.23), −1.77, 0.08 | 0.67 (−33.3%) [0.43, 1.04] | ← → |

| (1.3) | (1.6) | (1.8) | (1.7) | T1 vs. T3 | −0.31 (0.27), −1.13, 0.26 | 0.73 (−26.6%) [0.43, 1.26] | ← → | |

| T1 vs. T4 | −0.17 (0.34), −0.51, 0.61 | 0.84 (−15.7%) [0.44, 1.63] | ← → | |||||

| T2 vs. T3 | 0.10 (0.27), 0.35, 0.73 | 1.10 (+10.1%) [0.64, 1.88] | ← → | |||||

| T2 vs. T4 | 0.23 (0.37), 0.63, 0.53 | 1.26 (+26.4%) [0.61, 2.63] | ← → | |||||

| T3 vs. T4 | 0.14 (0.35), 0.39, 0.70 | 1.15 (+14.9%) [0.57, 2.30] | ← → | |||||

| PSC_NHT | 3.5 | 3.4 | 3.0 | 3.3 | T1 vs. T2 | <0.01 (0.29), <0.01, 0.100 | 1.00 (+0.2%) [0.57, 1.77] | ← → |

| (1.1) | (1.4) | (1.1) | (1.2) | T1 vs. T3 | 0.43 (0.29), 1.46, 0.14 | 1.53 (+53.5%) [0.86, 2.72] | ← → | |

| T1 vs. T4 | 0.18 (0.30), 0.60, 0.55 | 1.20 (+19.8%) [0.66, 2.16] | ← → | |||||

| T2 vs. T3 | 0.43 (0.26), 1.62, 0.10 | 1.53 (+53.2%) [0.91, 2.57] | ← → | |||||

| T2 vs. T4 | 0.18 (0.36), 0.49, 0.62 | 1.20 (+19.6%) [0.59, 2.44] | ← → | |||||

| T3 vs. T4 | −0.25 (0.38), −0.65, 0.52 | 0.78 (−21.9%) [0.37, 1.65] | ← → | |||||

| TDF_KNO | NA | 1.6 | 1.2 | NA | T2 vs. T3 | 0.97 (0.29), 3.39, <0.001 | 2.64 (+164.1%) [1.51, 4.63] | ↑ *** |

| (0.5) | (0.3) | |||||||

| TDF_SKI | NA | 1.6 | 1.2 | NA | T2 vs. T3 | 0.98 (0.28), 3.49, <0.001 | 2.68 (+167.7%) [1.54, 4.65] | ↑ *** |

| (0.6) | (0.4) | |||||||

| TDF_PRO | NA | 1.8 | 1.6 | 1.7 | T2 vs. T3 | 0.33 (0.29), 1.13, 0.26 | 1.39 (+38.7%) [0.79, 2.44] | ← → |

| (0.8) | (0.7) | (0.6) | T2 vs. T4 | 0.16 (0.30), 0.52, 0.60 | 1.17 (+16.8%) [0.65, 2.09] | ← → | ||

| T3 vs. T4 | −0.17 (0.33), −0.51, 0.61 | 0.84 (−15.8%) [0.44, 1.62] | ← → | |||||

| TDF_BELCA | NA | 1.7 | 1.7 | 1.7 | T2 vs. T3 | 0.13 (0.26), 0.49, 0.63 | 1.14 (+13.7%) [0.68, 1.91] | ← → |

| (0.5) | (0.5) | (0.5) | T2 vs. T4 | <0.01 (0.27), 0.04, 0.97 | 1.01 (+1.0%) [0.60, 1.70] | ← → | ||

| T3 vs. T4 | −0.12 (0.25), −0.47, 0.64 | 0.89 (−11.2%) [0.54, 1.46] | ← → | |||||

| TDF_BELCO | NA | 2.4 | 2.9 | 2.8 | T2 vs. T3 | −0.47 (0.15), −3.05, 0.002 | 0.62 (−37.5%) [0.46, 0.85] | ↑ *** |

| (0.4) | (0.5) | (0.4) | T2 vs. T4 | −0.34 (0.19), −1.80, 0.07 | 0.71 (−29.0%) [0.49, 1.03] | ← → | ||

| T3 vs. T4 | 0.13 (0.16), 0.80, 0.42 | 1.14 (+13.7%) [0.83, 1.56] | ← → | |||||

| TDF_OPT | NA | 2.1 | 2.1 | 2.1 | T2 vs. T3 | 0.05 (0.29), 0.16, 0.88 | 1.05 (+4.6%) [0.59, 1.85] | ← → |

| (0.7) | (0.6) | (0.7) | T2 vs. T4 | 0.12 (0.32), 0.37, 0.71 | 1.12 (+12.5%) [0.60, 2.09] | ← → | ||

| T3 vs. T4 | 0.07 (0.32), 0.23, 0.82 | 1.07 (+7.5%) [0.57, 2.01] | ← → | |||||

| TDF_INT | NA | 58.6 | 64.1 | 57.0 | T2 vs. T3 | −0.09 (0.19), −0.48, 0.63 | 0.91 (−8.9%) [0.62, 1.33] | ← → |

| (36.0) | (32.9) | (36.1) | T2 vs. T4 | 0.15 (0.29), 0.54, 0.59 | 1.17 (+16.6%) [0.66, 2.05] | ← → | ||

| T3 vs. T4 | 0.25 (0.28), 0.89, 0.37 | 1.28 (+28.0%) [0.74, 2.21] | ← → | |||||

| ProQOL_B | 19.1 | 20.4 | 20.6 | 21.6 | T1 vs. T2 | −0.20 (0.16), −1.29, 0.20 | 0.82 (−18.1%) [0.60, 1.11] | ← → |

| (4.2) | (4.8) | (5.1) | (4.6) | T1 vs. T3 | −0.29 (0.19), −1.50, 0.13 | 0.75 (−25.4%) [0.51, 1.09] | ← → | |

| T1 vs. T4 | −0.41 (0.21), −1.91, 0.06 | 0.66 (−33.6%) [0.44, 1.01] | ← → | |||||

| T2 vs. T3 | −0.09 (0.19), −0.49, 0.62 | 0.91 (−8.9%) [0.63, 1.32] | ← → | |||||

| T2 vs. T4 | −0.21 (0.20), −1.03, 0.31 | 0.81 (−18.9%) [0.54, 1.21] | ← → | |||||

| T3 vs. T4 | −0.12 (0.23), −0.50, 0.62 | 0.89 (−11.0%) [0.57, 1.40] | ← → | |||||

| ProQOL_C | 43.0 (5.4) | 42.6 (5.7) | 41.7 (5.9) | 41.9 (5.3) | T1 vs. T2 | 0.04 (0.13), 0.30, 0.76 | 1.04 (+4.0%) [0.81, 1.34] | ← → |

| T1 vs. T3 | 0.17 (0.17), 0.99, 0.32 | 1.18 (+18.2%) [0.85, 1.64] | ← → | |||||

| T1 vs. T4 | 0.18 (0.16), 1.13, 0.26 | 1.20 (+19.7%) [0.88, 1.63] | ← → | |||||

| T2 vs. T3 | 0.13 (0.18), 0.70, 0.49 | 1.14 (+13.6%) [0.79, 1.63] | ← → | |||||

| T2 vs. T4 | 0.14 (0.18), 0.76, 0.45 | 1.15 (+15.1%) [0.80, 1.65] | ← → | |||||

| T3 vs. T4 | 0.01 (0.20), 0.06, 0.95 | 1.01 (+1.3%) [0.69, 1.49] | ← → | |||||

| ProQOL_STS | 16.6 (3.7) | 17.5 (4.1) | 18.1 (4.5) | 17.3 (4.5) | T1 vs. T2 | −0.21 (0.18), −1.17, 0.24 | 0.81 (−18.8%) [0.57, 1.15] | ← → |

| T1 vs. T3 | −0.33 (0.19), −1.68, 0.09 | 0.72 (−27.8%) [0.49, 1.06] | ← → | |||||

| T1 vs. T4 | −0.28 (0.17), −1.62, 0.10 | 0.76 (−24.5%) [0.54, 1.06] | ← → | |||||

| T2 vs. T3 | −0.12 (0.21), −0.56, 0.58 | 0.89 (−11.1%) [0.59, 1.35] | ← → | |||||

| T2 vs. T4 | −0.07 (0.20), −0.36, 0.72 | 0.93 (−7.0%) [0.63, 1.38] | ← → | |||||

| T3 vs. T4 | 0.05 (0.21), 0.21, 0.83 | 1.05 (+4.6%) [0.69, 1.59] | ← → |

| Realist Evaluation | Question | Thematic Responses (Number of Participants) | Example Quotes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Outcomes | Explain how BASE-HCP training influenced your current delivery of care/current practice | Improvements in evidence-based knowledge for practice (8): Behaviour change principles (3), exercise benefits (1), exercise guidelines (1), telehealth methods (1), MS care (2) New techniques adopted in practice (10): Behaviour change techniques (5), telehealth exercise promotion (5) Enhanced practice confidence (7): Telehealth exercise promotion (5), MS management (2) (n = 14) | “I have implemented more goal-oriented sessions, improving my education of this population.” “I have thought more about the behaviour change component and placed more time looking into things like participants’ beliefs around exercises, etc, than perhaps I did in the past.” “I feel more confident prescribing and progressing walking programs and resistance exercises over Telehealth. I feel more confident in assessing and managing clients with MS, more broadly.” |

| If you applied any of the BASE-HCP knowledge to non-MS patients, what parts or elements of the BASE training do you apply to these clients and how? | Behaviour change principles (7) Exercise prescription (3) Patient self-report of exercise (1) (n = 11) | “I apply the basic principles of behaviour change to facilitate adherence to the exercise program, as well as the exercises themselves and progressions.” “Barriers & Facilitators—educating and recording the client on these principles. Goal Setting—the SMART principle, particularly with the NDIS scheme, and reviewing them regularly.” “The main thing I’ve implemented since the BASE programme is providing a consistent programme for 8–12 weeks with the client’s active tracking of what they are doing. I progressed in the programme when I met with them. It has freed up some time as my clients are more self-sufficient with generalised exercise to maintain their physical well-being, and my physiotherapy sessions can focus more on targeted intervention for challenge areas.” |

| Implementation Construct | Realist Evaluation | Question | Thematic Responses | Example Quotes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Appropriateness | ||||

| Professional delivery | Contexts | Under what circumstances would you recommend the BASE program to other clinicians, within the same clinical profession as yourself, to deliver to their MS clients? | Suitable HCPs: new graduates, need telehealth experience, need remote professional development Suitable clients: remote/rural, non-NDIS, those with anxiety leaving the home, those with low exercise motivation, those with good digital literacy, those with general exercise needs who follow structure well | “Any clinician (physio/EP) wanting to improve clinical practice & bridge their evidence-practice gap. The BASE program can have future success with peer-learning and discussions on improving clinical practice, having a follow-on effect in the healthcare system.” “If their clients are remote and not exercising already.” |

| Under what circumstances would you NOT recommend the BASE program to other clinicians, within the same clinical profession as yourself, to deliver to their MS clients? | Unsuitable HCPs: students/new graduates, those with minimal time or no interest in the programme Unsuitable clients: highly disabled with complex needs (falls risk, cognitive challenges, high mobility disability) requiring in-person support, highly active with higher exercise capacity | “Clinicians with less than 2 years’ experience (and it can be more difficult to coach/assess/check technique/build rapport online).” “When there is a clinical indication for further assessment that requires in-person review and exercise modification.” | ||

| Under what circumstances would you recommend the BASE program to other clinicians, within a different clinical profession than yourself, to deliver to their MS clients? | Suitable HCPs: those new to MS, those with fatigue and disability awareness, those with exercise knowledge (physiotherapists, exercise physiologists, occupational therapists, GPs, doctors and nurses, allied health assistants, speech pathologists, social workers, and dieticians). | “If I felt they had a suitable knowledge and confidence around MS and exercise, I believe they would be more than capable—it is easy to administer, if they can provide continued information when clients have questions.” | ||

| Under what circumstances would you NOT recommend the BASE program to other clinicians, within a different clinical profession than yourself, to deliver to their MS clients? | Unsuitable HCPs: those with no MS or degenerative condition experience, chiropractors/osteopaths, passive treating HCPs, those working outside their scope of practice, those without exercise experience, those without motivation or time to deliver the program. Unsuitable clients: those with complex needs/higher disability, newly diagnosed clients needing close exercise advice | “If they did not have enough confidence and desire to learn the knowledge, if they didn’t have experience with MS clients or exercise prescription and if they did not know/believe the benefits of exercise for MS.” “Patients who have not first consulted an exercise physiologist or physiotherapist to assess their suitability for the program.” | ||

| Suggested adaptations for BASE-HCP | Mechanisms | What changes could be made to the BASE program, which would help you to implement this more easily and widely within your clinical practice? | Learning component Course structure and delivery: make all lectures mandatory, include more case studies and role play scenarios, improve quiz question clarity Content additions and expansion: add topics (fatigue management, heat sensitivity, interval training, navigating relapse and exercise, strategies for exercise regression, therapist project management), expand scope of content to other neurological conditions, add advanced content for more experienced HCPs Application component Program structure modifications: add screening for fall risk, offer shorter program options (12–13 weeks) with deload weeks, include in-person session(s), initial set-up coaching calls Exercise content: include additional MS/exercise information, expand exercise options (including a greater variety of difficulty levels) PDF manual: shorten content, add timetables, add hyperlinks; consider separate manuals for learning vs. application, provide paper diaries as an alternative format option Technology improvements: simplify online spreadsheet data entry, implement auto-populated exercise prescriptions, automate emails/texts, develop HCP planner functionality Support and resources: discuss HCP insurance considerations, provide participant training videos for spreadsheets, provide post-program referral to local resources, and provide HCPs with more equipment | “I found the learning component quite dry. There was a lot of sitting and listening. Something more interesting than watching a recorded PowerPoint.” “The content was good. More education and guidelines on how to manage exercise/program during relapses, when patients have high fatigue or anxiety.” “A few clients encountered sicknesses, injuries (chronic and acute)—often having deload can aid in this and also guide improved long-term muscular strength/health benefits.” “More clarity on parameters regarding variation on exercise progression/ Regression.” “The lectures and content before the implementation were comprehensive and greatly helped during the 16 weeks. I appreciated all the information included in the manuals.” “Too much data entry required by participants. If tracking all data, it would have taken 30+ min per day, which participants didn’t have.” “Understanding the legalities of working in an online setting (e.g., disclaimers, security of data/video platform being used, etc).” |

| Suggested adaptations for other health conditions | Mechanisms | What would need to change about the BASE training program to make it applicable for delivery in other health conditions? | Learning component: Provide population-specific modules (with changes to background, pathophysiology, and contraindications), and provide behaviour change coaching Application component: Exercise prescription adaptations: tailor exercise prescription to population, provide greater variety in aerobic exercise options, provide seated exercise options for conditions/individuals with low mobility, incorporate individualisation Support considerations: consider unique support needs, make communications (e.g., newsletters) generic or disease-specific, and provide condition-specific outcome measures | “Each health condition has its specific details and degree of variation. I think background information on health conditions and the evidence to support the benefit of exercise specific to that condition is very important.” “In Parkinson’s, probably tailoring some exercises to consider movement size and power.” “For mental health populations such as depression, PTSD, and anxiety, more psychological depth within the behaviour change modules would be needed, with more client coaching calls needed in the program.” |

| Feasibility | ||||

| Time commitment | Outcomes | Estimate how much time you spent completing the learning components of the programme (i.e., lectures, quizzes, and revision) | Lectures: Median = 4 h Quizzes: Median = 5–20 min per quiz Revision for application component: Median = 30 min | NA |

| Estimate how much time you spent completing the application components of the programme (per patient) | Coaching calls: Median = 35 min (note: first and last calls were ~45 min) Administrative tasks: Median = 20 min Other communications: Median = 15–30 min | |||

| Barriers to implementation | Mechanisms | Are there currently any barriers that would prevent you from implementing this program for more of your MS clients as part of your routine clinical practice? | The majority reported no barriers. Remaining barriers included: contextual factors (time commitment, no current MS patients, no remote patients, and the desire for more exercise prescription autonomy); patient-related barriers (highly disabled patients, poorly motivated patients); and technology & equipment barriers (equipment requirements/availability, complex/differing technology platforms) | “I would automate reminder messages and newsletter emails to save time.” “If my client were highly disabled or had frequent flareups or episodes of poor mobility /health, I would not see this as a good option for them. Face-to-face would be a much better way to determine their capacity/level to exercise.” |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Learmonth, Y.C.; Mavropalias, G.; Wansbrough, K. Evaluation of a Theoretical and Experiential Training Programme for Allied Healthcare Providers to Prescribe Exercise Among Persons with Multiple Sclerosis: A Co-Designed Effectiveness-Implementation Study. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 6625. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14186625

Learmonth YC, Mavropalias G, Wansbrough K. Evaluation of a Theoretical and Experiential Training Programme for Allied Healthcare Providers to Prescribe Exercise Among Persons with Multiple Sclerosis: A Co-Designed Effectiveness-Implementation Study. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(18):6625. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14186625

Chicago/Turabian StyleLearmonth, Yvonne C., Georgios Mavropalias, and Kym Wansbrough. 2025. "Evaluation of a Theoretical and Experiential Training Programme for Allied Healthcare Providers to Prescribe Exercise Among Persons with Multiple Sclerosis: A Co-Designed Effectiveness-Implementation Study" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 18: 6625. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14186625

APA StyleLearmonth, Y. C., Mavropalias, G., & Wansbrough, K. (2025). Evaluation of a Theoretical and Experiential Training Programme for Allied Healthcare Providers to Prescribe Exercise Among Persons with Multiple Sclerosis: A Co-Designed Effectiveness-Implementation Study. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(18), 6625. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14186625