Intermediate Care Units in Europe and Italy: A Review of Structure, Outcomes, and Policy Implications for Internal Medicine

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Search Strategy and Scope

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

2.3. Data Synthesis and Structure

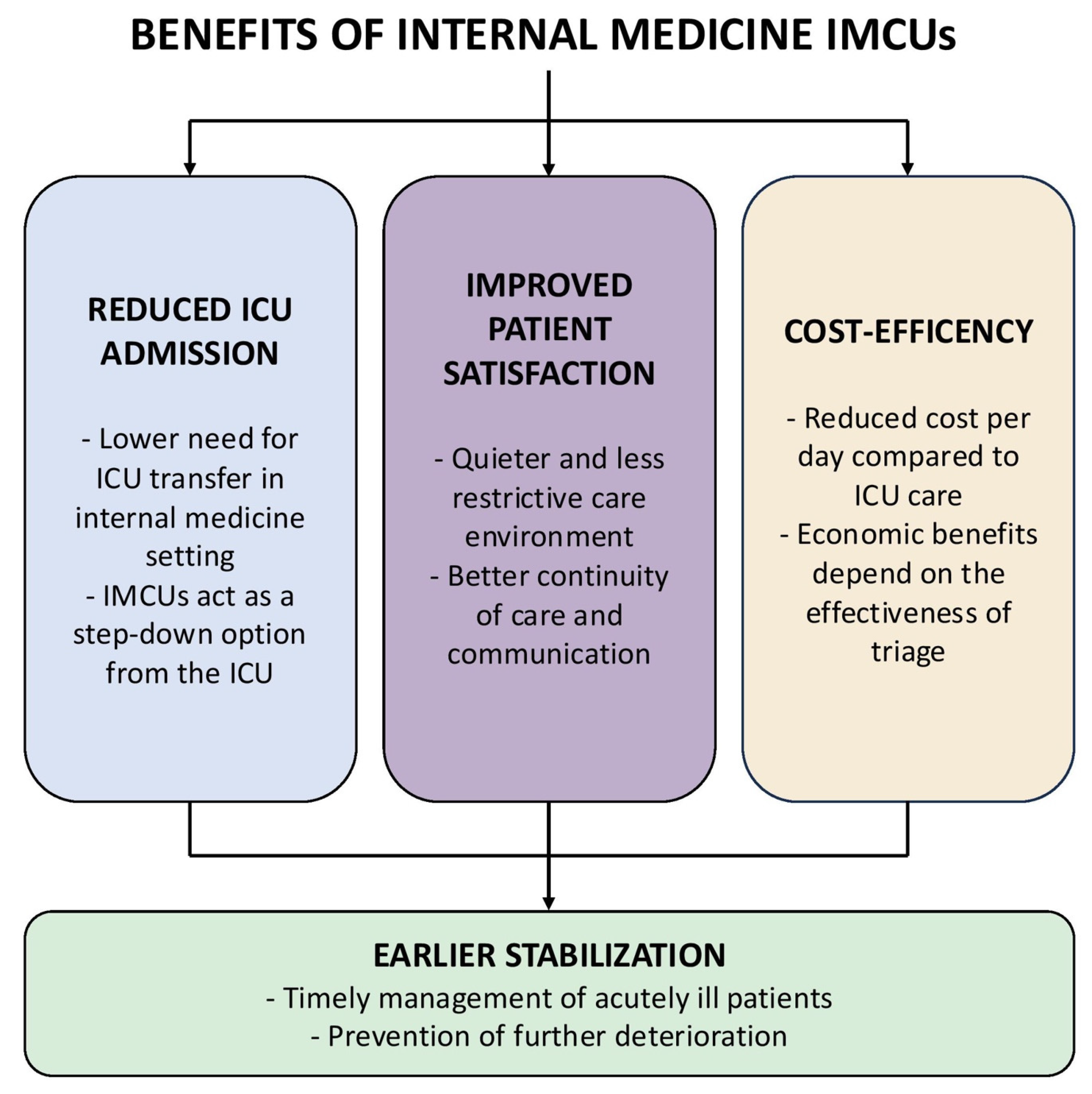

3. Clinical Effectiveness of IMCUs and Patient Outcomes

3.1. Impact on Mortality and Morbidity

3.2. Impact on Acute Stabilization

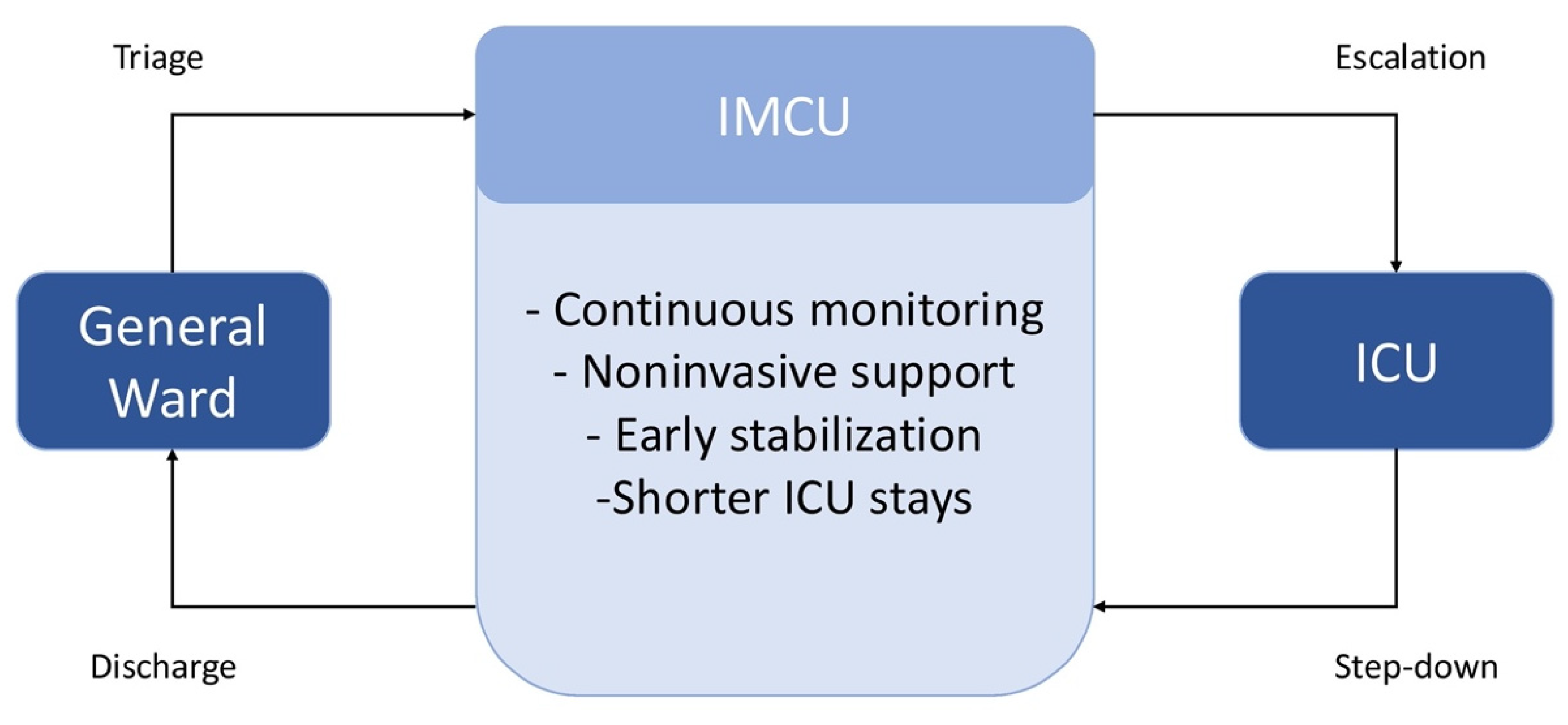

3.3. Effect on ICU Utilization and Patient Flow

3.4. Patient and Family Satisfaction, Comfort, and Quality of Life

3.5. Safety and Limitations

4. Cost-Effectiveness Considerations

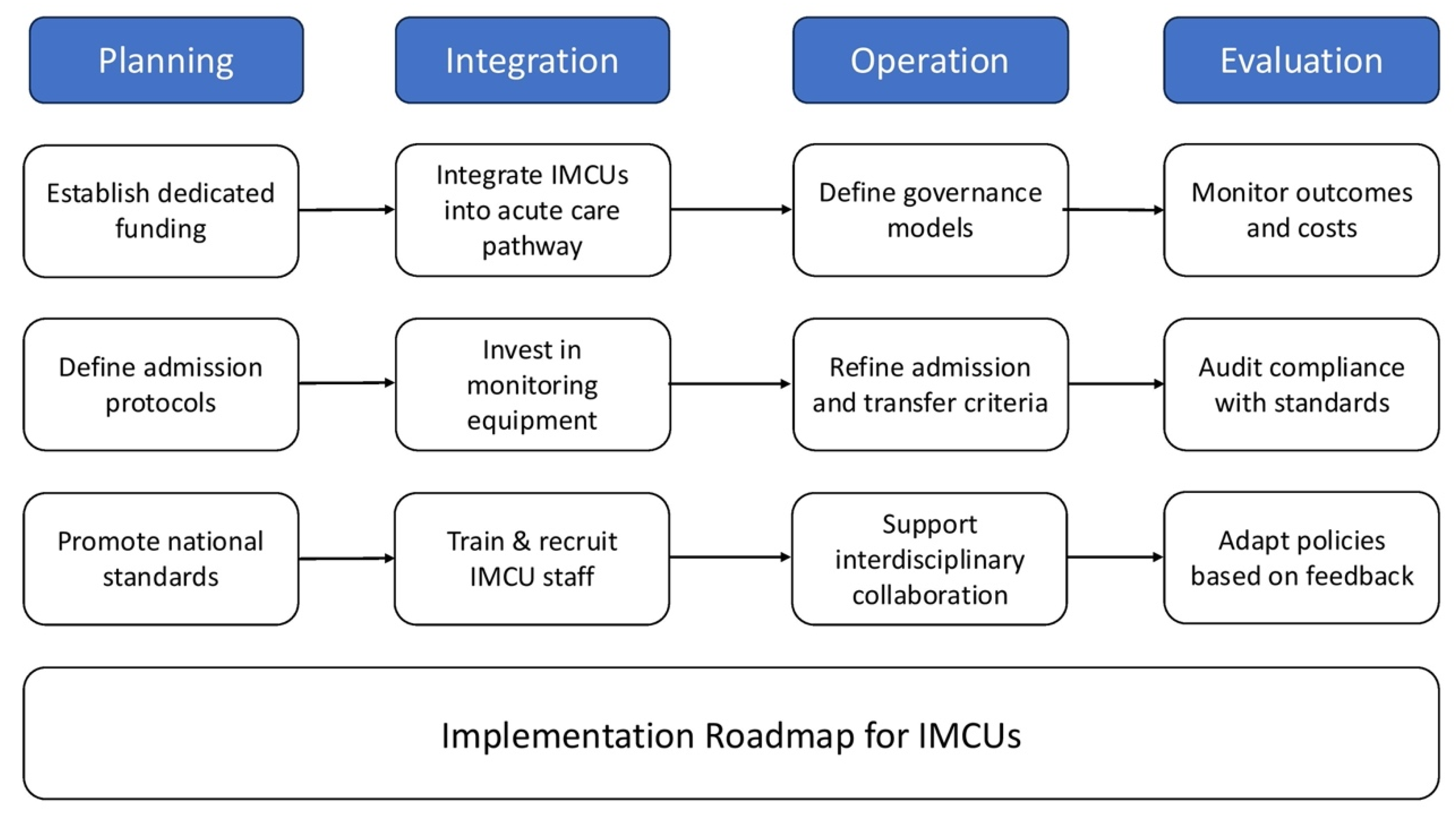

5. Implementation

5.1. Policy Directions

5.2. Operational Requirements and Governance

5.2.1. Investment in Equipment and Staff

5.2.2. Governance Models and Structural Integration

5.3. Admission Criteria and Key Factors for Feasibility

6. The Establishment of Sub-Intensive Care Units in Italy

7. Limitations

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Vincent, J.-L.; Rubenfeld, G.D. Does Intermediate Care Improve Patient Outcomes or Reduce Costs? Crit. Care 2015, 19, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prin, M.; Wunsch, H. The Role of Stepdown Beds in Hospital Care. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2014, 190, 1210–1216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakr, Y.; Moreira, C.L.; Rhodes, A.; Ferguson, N.D.; Kleinpell, R.; Pickkers, P.; Kuiper, M.A.; Lipman, J.; Vincent, J.-L. Extended Prevalence of Infection in Intensive Care Study Investigators The Impact of Hospital and ICU Organizational Factors on Outcome in Critically Ill Patients: Results from the Extended Prevalence of Infection in Intensive Care Study. Crit. Care Med. 2015, 43, 519–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Jardón, P.; Martínez-Fernández, M.C.; García-Fernández, R.; Martín-Vázquez, C.; Verdeal-Dacal, R. Utility of Intermediate Care Units: A Systematic Review Study. Healthcare 2024, 12, 296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waydhas, C.; Herting, E.; Kluge, S.; Markewitz, A.; Marx, G.; Muhl, E.; Nicolai, T.; Notz, K.; Parvu, V.; Quintel, M.; et al. Intermediate Care Units. Med. Klin. Intensivmed. Notfmed 2018, 113, 33–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capuzzo, M.; Volta, C.; Tassinati, T.; Moreno, R.; Valentin, A.; Guidet, B.; Iapichino, G.; Martin, C.; Perneger, T.; Combescure, C.; et al. Hospital Mortality of Adults Admitted to Intensive Care Units in Hospitals with and without Intermediate Care Units: A Multicentre European Cohort Study. Crit. Care 2014, 18, 551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohbe, H.; Kudo, D.; Kimura, Y.; Matsui, H.; Yasunaga, H.; Kushimoto, S. In-Hospital Mortality of Patients Admitted to the Intermediate Care Unit in Hospitals with and without an Intensive Care Unit: A Nationwide Inpatient Database Study. Crit. Care 2025, 29, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Confalonieri, M.; Gorini, M.; Ambrosino, N.; Mollica, C.; Corrado, A. Respiratory Intensive Care Units in Italy: A National Census and Prospective Cohort Study. Thorax 2001, 56, 373–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, H.J.; Coggins, R.; Lafuente, J.; de Cossart, L. Value of a Surgical High-Dependency Unit. Br. J. Surg. 1999, 86, 1578–1582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armstrong, K.; Young, J.; Hayburn, A.; Irish, B.; Nikoletti, S. Evaluating the Impact of a New High Dependency Unit. Int. J. Nurs. Pract. 2003, 9, 285–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heili-Frades, S.; Carballosa de Miguel, M.D.P.; Naya Prieto, A.; Galdeano Lozano, M.; Mate García, X.; Mahillo Fernández, I.; Fernández Ormaechea, I.; Álvarez Suárez, L.; Ezzine de Blas, F.; Checa Venegas, M.J.; et al. Cost and Mortality Analysis of an Intermediate Respiratory Care Unit. Is It Really Efficient and Safe? Arch. Bronconeumol. 2019, 55, 634–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turcato, G.; Zaboli, A.; Ferretto, P.; Filippi, L.; Milazzo, D.; Parodi, M.; Maggi, M.; Cipriano, A.; Marchetti, M.; Wiedermann, C.J.; et al. The Role of an Intermediate Care Unit in Reducing Intensive Care Unit Admissions and Improving Patient Outcomes in Internal Medicine: A Quasi-Experimental Study. Eur. J. Intern. Med. 2025, 137, 45–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin-Loeches, I.; Singer, M.; Leone, M. Sepsis: Key Insights, Future Directions, and Immediate Goals. A Review and Expert Opinion. Intensive Care Med. 2024, 50, 2043–2049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jentzer, J.C.; Tabi, M.; Burstein, B. Managing the First 120 Min of Cardiogenic Shock: From Resuscitation to Diagnosis. Curr. Opin. Crit. Care 2021, 27, 416–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, T.F.; Rabinstein, A.A.; Middlebrooks, E.H.; Haranhalli, N.; Silliman, S.L.; Meschia, J.F.; Tawk, R.G. Diagnosis and Management of Acute Ischemic Stroke. Mayo Clin. Proc. 2018, 93, 523–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turcato, G.; Zaboli, A.; Filippi, L.; Cipriano, A.; Ferretto, P.; Milazzo, D.; Sabbà, G.E.; Maggi, M.; Marchetti, M.; Wiedermann, C.J. Improving Acute Care Outcome in Internal Medicine: The Role of Early Stabilization and Intermediate Care Unit. Intern. Emerg. Med. 2025, 20, 453–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kistler, E.A.; Klatt, E.; Raffa, J.D.; West, P.; Fitzgerald, J.A.; Barsamian, J.; Rollins, S.; Clements, C.M.; Hickox Murray, S.; Cocchi, M.N.; et al. Creation and Expansion of a Mixed Patient Intermediate Care Unit to Improve ICU Capacity. Crit. Care Explor. 2023, 5, e0994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eachempati, S.R.; Hydo, L.J.; Barie, P.S. The Effect of an Intermediate Care Unit on the Demographics and Outcomes of a Surgical Intensive Care Unit Population. Arch. Surg. 2004, 139, 315–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Franklin, C.M.; Rackow, E.C.; Mamdani, B.; Nightingale, S.; Burke, G.; Weil, M.H. Decreases in Mortality on a Large Urban Medical Service by Facilitating Access to Critical Care. An Alternative to Rationing. Arch. Intern. Med. 1988, 148, 1403–1405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, D.C.; Byrick, R.J.; Knobel, E. Structural Models for Intermediate Care Areas. Crit. Care Med. 1999, 27, 2266–2271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galdeano Lozano, M.; Alfaro Álvarez, J.C.; Parra Macías, N.; Salas Campos, R.; Heili Frades, S.; Montserrat, J.M.; Rosell Gratacós, A.; Abad Capa, J.; Parra Ordaz, O.; López Seguí, F. Effectiveness of Intermediate Respiratory Care Units as an Alternative to Intensive Care Units during the COVID-19 Pandemic in Catalonia. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 6034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matute-Villacís, M.; Moisés, J.; Embid, C.; Armas, J.; Fernández, I.; Medina, M.; Ferrer, M.; Sibila, O.; Badia, J.R. Role of Respiratory Intermediate Care Units during the SARS-CoV-2 Pandemic. BMC Pulm. Med. 2021, 21, 228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suarez-Cuartin, G.; Gasa, M.; Bermudo, G.; Ruiz, Y.; Hernandez-Argudo, M.; Marin, A.; Trias-Sabria, P.; Cordoba, A.; Cuevas, E.; Sarasate, M.; et al. Clinical Outcomes of Severe COVID-19 Patients Admitted to an Intermediate Respiratory Care Unit. Front. Med. 2021, 8, 711027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alfonso-Megido, J.; Cárcaba Fernández, V. Intermediate Care Units dependent on Internal Medicine in a hospital without an Intensive Care Unit. Rev. Clin. Esp. 2007, 207, 144–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hager, D.N.; Dezube, R.; Disney, S.M. Models of Intermediate Care Organization and Staffing at an Academic Medical Center: Considerations of an Inpatient Planning Committee. J. Intensive Care Med. 2022, 37, 1288–1295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramos, J.G.R.; Dos Santos, G.M.N.; Bispo, M.C.C. Unplanned Transfers from Intermediate Care Units to Intensive Care Units: A Cohort Study. Am. J. Crit. Care 2021, 30, 397–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vincent, J.L.; Burchardi, H. Do We Need Intermediate Care Units? Intensive Care Med. 1999, 25, 1345–1349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertolini, G.; Confalonieri, M.; Rossi, C. Costs of the COPD. Differences between Intensive Care Unit and Respiratory Intermediate Care Unit. Respir. Med. 2005, 99, 894–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solberg, B.C.; Dirksen, C.D.; Nieman, F.H.; Merode, G.; Poeze, M.; Ramsay, G. Changes in Hospital Costs after Introducing an Intermediate Care Unit: A Comparative Observational Study. Crit. Care 2008, 12, R68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plate, J.D.J.; Peelen, L.M.; Leenen, L.P.H.; Hietbrink, F. The Intermediate Care Unit as a Cost-Reducing Critical Care Facility in Tertiary Referral Hospitals: A Single-Centre Observational Study. BMJ Open 2019, 9, e026359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senaratne, M.P.; Irwin, M.E.; Shaben, S. Feasibility of Direct Discharge from the Coronary/Intermediate Care Unit after Acute Myocardial Infarction. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 1999, 33, 1040–1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Confalonieri, M.; Trevisan, R.; Demšar, M.; Lattuada, L.; Longo, C.; Cifaldi, R.; Jevnikar, M.; Santagiuliana, M.; Pelusi, L.; Pistelli, R. Opening of a Respiratory Intermediate Care Unit in a General Hospital: Impact on Mortality and Other Outcomes. Respiration 2015, 90, 235–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scala, R. Respiratory High-Dependency Care Units for the Burden of Acute Respiratory Failure. Eur. J. Intern. Med. 2012, 23, 302–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scala, R.; Renda, T.; Corrado, A.; Vaghi, A. Italian Pulmonologist Units and COVID-19 Outbreak: “Mind the Gap”! Crit. Care 2020, 24, 381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Department of Health. The NHS Plan: A Plan for Investment, a Plan for Reform. Available online: https://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/ukgwa/+mp_/http://www.dh.gov.uk/en/publicationsandstatistics/publications/publicationspolicyandguidance/dh_4002960 (accessed on 5 July 2025).

- Hamsen, U.; Lefering, R.; Fisahn, C.; Schildhauer, T.A.; Waydhas, C. Workload and Severity of Illness of Patients on Intensive Care Units with Available Intermediate Care Units: A Multicenter Cohort Study. Minerva Anestesiol. 2018, 84, 938–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garfield, M.; Jeffrey, R.; Ridley, S. An Assessment of the Staffing Level Required for a High-Dependency Unit. Anaesthesia 2000, 55, 137–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liaw, S.Y.; Scherpbier, A.; Klainin-Yobas, P.; Rethans, J.J. A Review of Educational Strategies to Improve Nurses’ Roles in Recognizing and Responding to Deteriorating Patients. Int. Nurs. Rev. 2011, 58, 296–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Plate, J.D.J.; Leenen, L.P.H.; Houwert, M.; Hietbrink, F. Utilisation of Intermediate Care Units: A Systematic Review. Crit. Care Res. Pract. 2017, 2017, 8038460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wendlandt, B.; Bice, T.; Carson, S.; Chang, L. Intermediate Care Units: A Survey of Organization Practices Across the United States. J. Intensive Care Med. 2020, 35, 468–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canetta, C.; Accordino, S.; Sozzi, F.B. Intermediate Care Units in Internal Medicine. Eur. J. Intern. Med. 2025, 4, 55–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mermiri, M.; Mavrovounis, G.; Chatzis, D. Critical emergency medicine and the resuscitative care unit. Acute Crit. Care 2021, 36, 22–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Plate, J.D.J.; Peelen, L.M.; Leenen, L.P.H.; Houwert, R.M.; Hietbrink, F. Joint Management Format at the Mixed-Surgical Intermediate Care Unit: An Interrupted Time Series Analysis. Trauma. Surg. Acute Care Open 2018, 3, e000177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nates, J.L.; Nunnally, M.; Kleinpell, R. ICU Admission, Discharge, and Triage Guidelines: A Framework to Enhance Clinical Operations, Development of Institutional Policies, and Further Research. Crit. Care Med. 2016, 44, 1553–1602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manfellotto, D.; Pietrangelo, A.; Cogliato, C. Documento Sulla Riorganizzazione Delle UUOO di Medicina Interna. Available online: https://www.simi.it/news/riorganizzazione-uuoo-medicina-interna (accessed on 12 September 2025).

- Zambon, M. Terapie Intensive E Sub-Intensive: Modelli e Ipotesi di Razionalizzazione Ospedaliera in Epoca di Limitate Risorse Umane; PoliS-Lombardia: Milam, Italy, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Bülbül, H.; Derviş Hakim, G.; Ceylan, C.; Aysin, M.; Köse, Ş. What Is the Place of Intermediate Care Unit in Patients with COVID-19? A Single Center Experience. Int. J. Clin. Pract. 2023, 2023, 8545431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harding, A.D. What Can an Intermediate Care Unit Do for You? J. Nurs. Adm. 2009, 39, 4–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Misset, B.; Aegerter, P.; Boulkedid, R. Construction of Reference Criteria to Admit Patients to Intermediate Care Units in France: A Delphi Survey of Intensivists, Anaesthesiologists and Emergency Medicine Practitioners (First Part of the UNISURC Project. BMJ Open 2023, 13, e072836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jalal, A.; Iwamoto, K.; Gedik, G.; Ravaghi, H.; Kodama, C. Health Workforce Capacity of Intensive Care Units in the Eastern Mediterranean Region. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0286980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wowern, F.; Dalekos, G.N.D.; Gómez-Huelgas, R. Intermediate Care Units in Internal Medicine—From Concept to Consolidation. Eur. J. Intern. Med. 2025, 137, 35–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Domain | General Medical Ward | IMCU | ICU |

|---|---|---|---|

| Positioning & scope | Standard ward care with basic monitoring for low–moderate acuity patients. | “Level-2” care between ward and ICU; manages high-acuity patients not requiring full invasive organ support. | “Level-3” critical care with advanced invasive organ support and continuous monitoring. |

| Governance/integration | Ward-led pathways; escalation to IMCU/ICU when needed. | Should be structurally integrated with ED and ICU, with shared triage/escalation criteria and pathways. | ICU under accredited critical-care governance; benefits when an IMCU exists for step-down. |

| Core technologies/therapies | Selective telemetry; standard oxygen therapy. | Continuous monitoring; NIV/HFNC; telemetry; protocolized triage/escalation. | Invasive mechanical ventilation, RRT, multi-organ support. |

| Admission criteria (typical) | Clinically stable; low risk of rapid deterioration. | High-acuity patients without immediate indication for invasive supports; standardized admission/discharge criteria recommended. | Organ failure requiring invasive support or immediate critical care. |

| In-hospital LOS | May be longer for high-acuity patients when enhanced monitoring/support are unavailable. | Can reduce hospital LOS through earlier stabilization and smoother pathways (shown in respiratory IMCUs). | LOS may increase if step-down capacity is lacking; improved when IMCU enables earlier transfer. |

| Primary clinical goal | Routine care and recovery/discharge. | Early stabilization to avoid escalation and to enable safe step-down from ICU. | Stabilize the most critically ill with advanced supports. |

| Domain | Clinical Benefit | System Efficiency | Patient Experience |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mortality reduction | Yes [6,12,16] | — | — |

| ICU decongestion | — | Yes [1,17,18,30] | — |

| Early stabilization | Yes [16] | Yes [13,16] | — |

| Satisfaction and well-being | — | — | Yes [24,25] |

| Cost-effectiveness | — | Mixed [29,30] | — |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Turcato, G.; Zaboli, A.; Cipriano, A.; Montagnani, A.; Vannucchi, V.; Pieralli, F.; Belfiore, A.; Valbusa, F.; Marchetti, M.; Ferretto, P.; et al. Intermediate Care Units in Europe and Italy: A Review of Structure, Outcomes, and Policy Implications for Internal Medicine. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 6543. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14186543

Turcato G, Zaboli A, Cipriano A, Montagnani A, Vannucchi V, Pieralli F, Belfiore A, Valbusa F, Marchetti M, Ferretto P, et al. Intermediate Care Units in Europe and Italy: A Review of Structure, Outcomes, and Policy Implications for Internal Medicine. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(18):6543. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14186543

Chicago/Turabian StyleTurcato, Gianni, Arian Zaboli, Alessandro Cipriano, Andrea Montagnani, Vieri Vannucchi, Filippo Pieralli, Anna Belfiore, Filippo Valbusa, Massimo Marchetti, Paolo Ferretto, and et al. 2025. "Intermediate Care Units in Europe and Italy: A Review of Structure, Outcomes, and Policy Implications for Internal Medicine" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 18: 6543. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14186543

APA StyleTurcato, G., Zaboli, A., Cipriano, A., Montagnani, A., Vannucchi, V., Pieralli, F., Belfiore, A., Valbusa, F., Marchetti, M., Ferretto, P., Filippi, L., Voza, A., Ghiadoni, L., Ageno, W., & Wiedermann, C. J. (2025). Intermediate Care Units in Europe and Italy: A Review of Structure, Outcomes, and Policy Implications for Internal Medicine. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(18), 6543. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14186543