Living After Pelvic Exenteration: A Mixed-Methods Synthesis of Quality-of-Life Outcomes and Patient Perspectives

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Qualitative Component—Semi-Structured Interviews

2.2. Narrative Component—Literature Review

3. Results

3.1. Qualitative Component—Semi-Structured Interviews

3.2. Narrative Component—Literature Review

4. Discussion

- Bodily disruption and the experience of vulnerability: The physical transformation caused by the exenteration, particularly the presence of stomas and altered pelvic anatomy, was often perceived as a “second illness” distinct from the cancer. Patients often used powerful body metaphors to describe their post-operative bodies, calling themselves “cut”, “mutilated”, or “artificial”. This disruption was deeply connected to a sense of loss of autonomy and control over basic functions. As one participant put it: “It wasn’t just the illness that left me powerless. It was waking up with holes, tubes, and smells that weren’t mine.”.

- Rethinking identity and relational isolation: For many women, the loss of their pelvic organs symbolized not only a physical trauma but also a disruption of sexual identity. The absence of vaginal function or the presence of a colostomy was often associated with feelings of shame, desexualization, or self-alienation. Participants described a reduction in their social and relational world, often characterized by fear of intimacy and withdrawal from partners. However, in some cases, supportive relationships became sources of resistance. One participant said, “My wife is my support, she has always been there for me…”.

- Meaning-making and post-traumatic reorientation: Despite the invasive nature of the surgery, many patients described a gradual process of adaptation and even personal growth. This transition often involved a reassessment of life priorities, spiritual reflection, and a redefinition of survival over physical integrity. For some, the experience fostered a new sense of empowerment. “I never thought I could go through this and still laugh. But here I am.” said one patient. Those who regained independence in daily activities, such as stoma management or mobility, often reported a renewed sense of dignity and purpose.

4.1. Self-Image

Patient 1: “Of course I knew I would wake up with two stoma bags, but seeing myself like this was shocking for me. It took me a long time to get used to it…even now I can’t look at myself properly in the mirror…”.

Patient 2: “I changed my clothing style so that it wouldn’t be visible…I started wearing looser, darker clothes.”

Patient 3: “I don’t regret the surgery…I had no other choice…but I felt mutilated. I am happy that I don’t have pain anymore, that I don’t bleed anymore, that I don’t smell anymore…but I’ve realized that I would live like this for the rest of my life…”.

4.2. Social Impact (Social Interactions, Sexual Function, Family Relationships, Recreational and Professional Activities)

Patient 3: “I was afraid to play with my grandchildren because the stoma pouch might come off…I avoided them for a while…the little ones…I felt guilty but the fear was great. But as I learned to handle the pouch better, I was able to come back to them…last week I went to my niece’s party”.

Patient 1: “I was depressed for a long time…I only left the house to go to the doctor. It didn’t help that after about a year my husband left… he got tired…of going to the doctor, of the stoma, of me…”.

Patient 5: “My wife is my support, she has always been there for me…”.

Patient 4: “After the surgery I couldn’t anymore…I didn’t expect it to be like this.”

Patient 2: “I wasn’t menopausal before…The hot flashes…and the hormonal changes…I didn’t need it anymore, i didn’t want it beacuse it hurt me so much”

Patient 3: “When you don’t have a vagina anymore, sex is completely out of the question. Luckily we were already quite old and weren’t that active anymore…we have a different kind of intimacy now, which isn’t necessarily about sex, but which is just as important, if not more so…Not feeling alone is a blessing.”

Patient 5: “Before, I liked going out with friends, walking with my husband in the park… After the operation, I avoided doing these things for a long time…it seemed to me that people were pointing fingers at me. Worse, I thought that the bag would come off and I would make a fool of myself…I had even had nightmares about it. It was only after a year or so that I managed to find the courage to go out into the world again. But I’m still avoiding going in places where I know I don’t have easy access to a bathroom.”

Patient 5: “If it weren’t for my wife, I don’t know what I would have done. I didn’t even know how to change the stoma bags properly. I tortured her a lot this year…”.

Patient 1: “I retired. I couldn’t work anymore. After my husband left, it was just me and my mother… instead of me helping her, the poor woman had to bring me to the doctor. I couldn’t come every time… we live far away”.

Patient 2: “I didn’t work anymore after… I felt bad. Luckily my family helped me and we were able to compensate for the decrease in income”.

Patient 4: “I was retired before the surgery, but the costs of transportation, coming to the hospital, and the investigations are high…”.

4.3. Expectations Regarding Treatment

Patient 2: “I went to many doctors who all told me that they couldn’t do anything for me…that I came too late…I was very happy when I found the doctor who said he would operate on me. Everyone else sent me home to die…”

Patient 3: “I was bleeding so hard and I could barely stand. I smelled horrible, I had burns on my thighs from the feacal matter that was flowing uncontrollably…It was no life. I would have done anything to escape regardless of the risks.”

4.4. Symptom Control

4.5. Psychological Impact

4.6. Strengths, Limitations, and Future Research Directions

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AuQoL | Australian Quality of Life Questionnaire |

| BDI | Beck Depression Inventory |

| BFI | Big Five Inventory questionnaire |

| BPI-SF | Brief Pain Inventory-Short Form |

| CARES | Cancer Rehabilitation Evaluation System |

| CASP | Critical Appraisal Skills Programme |

| CES-D | Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale |

| CRC | Colorectal Cancer |

| DSFI | Derogatis Sexual Functioning Inventory |

| DT | Distress Thermometer Scale |

| EORTC | European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer |

| EORTC QLQ-BLM30 | European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire-Bladder Cancer Module |

| EORTC QLQ-C30 | European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire-Core 30 |

| EORTC QLQ-CR38 | European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire-Colorectal Cancer Module |

| EORTC QLQ-OV28 | European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire-Ovarian Cancer Module |

| FACT-C | Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-Colorectal questionnaire |

| HTH | Heterosexual Behavior Hierarchy |

| IADL | Instrumental Activities of Daily Living Scale questionnaire |

| IES-R | Revised Impact of Events Scale |

| IOB | Bucharest Institute of Oncology |

| KAS-R | Katz Social Adjustment Scale |

| MAT | Marital Adjustment Test |

| N | Sample size |

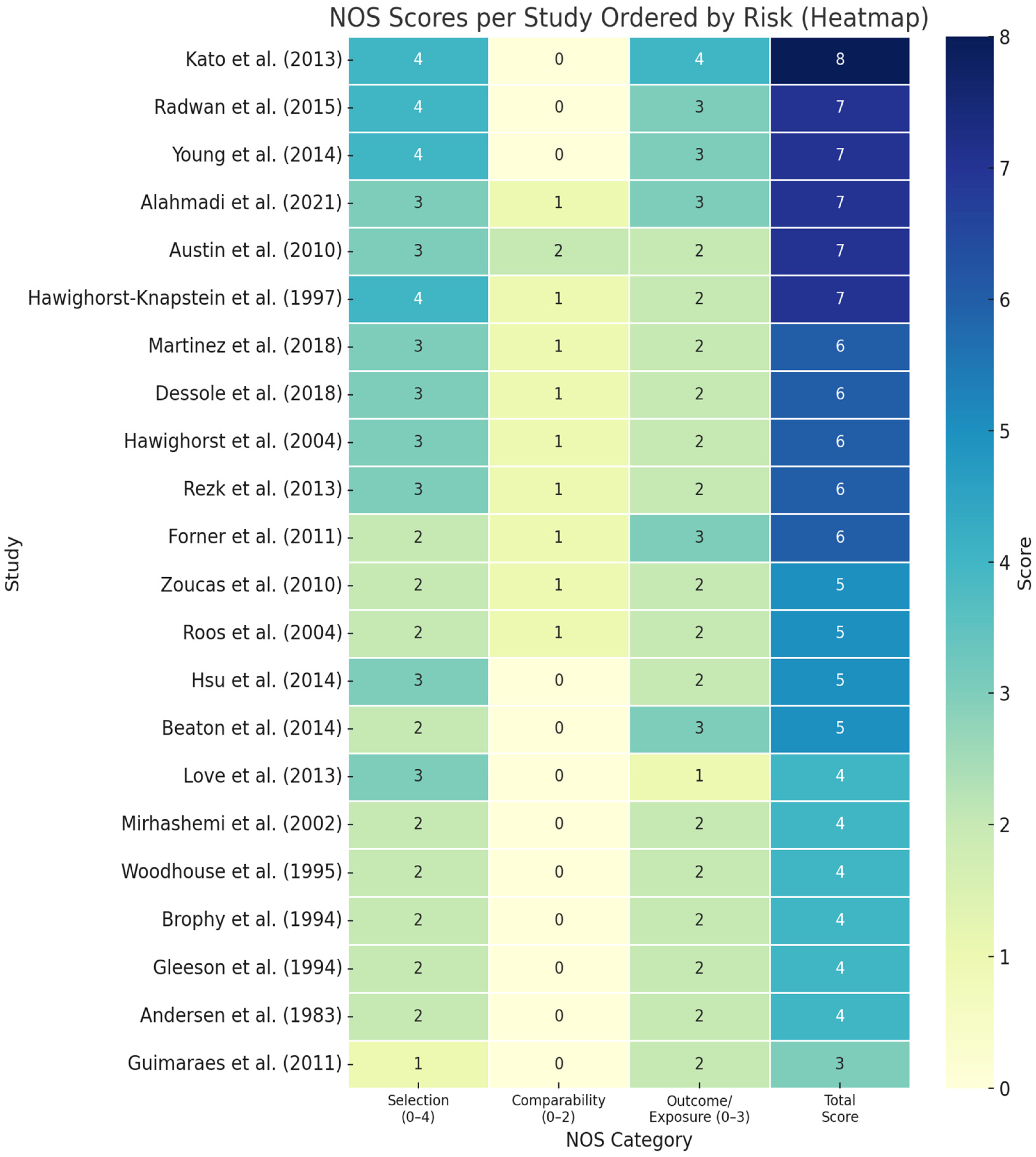

| NOS | Newcastle–Ottawa Scale |

| PE | Pelvic Exenteration |

| PRO | Patient-Reported Outcome |

| QLQ | Quality of Life Questionnaire |

| QoL | Quality of Life |

| SAI | State Anxiety Inventory |

| SCL90 | Symptom Checklist-90 questionnaire |

| SF-12 | Short Form-12 Health Survey Questionnaire |

| SF-36 | 36-Item Short Form Survey Instrument |

| SVQ | Sexual function-Vaginal changes questionnaire |

| UDI-6 | Urogenital Distress Inventory-6 |

| VRAM | Vertical Rectus Abdominis Myocutaneous |

References

- Brunschwig, A. Complete excision of pelvic viscera for advanced carcinoma: A one-stage abdominoperineal operation with end colostomy and bilateral ureteral implantation into the colon above the colostomy. Cancer 1948, 1, 177–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, J.M.; Badgery-Parker, T.; Masya, L.M.; King, M.; Koh, C.; Lynch, A.C.; Heriot, A.G.; Solomon, M.J. Quality of life and other patient-reported outcomes following exenteration for pelvic malignancy. Br. J. Surg. 2014, 101, 277–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zoucas, E.; Frederiksen, S.; Lydrup, M.L.; Månsson, W.; Gustafson, P.; Alberius, P. Pelvic exenteration for advanced and recurrent malignancy. World J. Surg. 2010, 34, 2177–2184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rotaru, V.; Chitoran, E.; Zob, D.L.; Ionescu, S.O.; Aisa, G.; Andra-Delia, P.; Serban, D.; Stefan, D.-C.; Simion, L. Pelvic Exenteration in Advanced, Recurrent or Synchronous Cancers—Last Resort or Therapeutic Option? Diagnostics 2024, 14, 1707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dessole, M.; Petrillo, M.; Lucidi, A.; Naldini, A.; Rossi, M.; De Iaco, P.; Marnitz, S.; Sehouli, J.; Scambia, G.; Chiantera, V. Quality of life in women after pelvic exenteration for gynecological malignancies: A multicentric study. Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer 2018, 28, 267–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alahmadi, R.; Steffens, D.; Solomon, M.J.; Lee, P.J.; Austin, K.K.S.; Koh, C.E. Elderly Patients Have Better Quality of Life but Worse Survival Following Pelvic Exenteration: A 25-Year Single-Center Experience. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2021, 28, 5226–5235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beaton, J.; Carey, S.; Solomon, M.J.; Tan, K.K.; Young, J. Preoperative Body Mass Index, 30-Day Postoperative Morbidity, Length of Stay and Quality of Life in Patients Undergoing Pelvic Exenteration Surgery for Recurrent and Locally-Advanced Rectal Cancer. Ann. Coloproctol. 2014, 30, 83–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, K.G.M.; Solomon, M.J. Understanding Quality of Life After Pelvic Exenteration for Patients with Rectal Cancer. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2024, 31, 7668–7670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steffens, D.; Solomon, M.J.; Karunaratne, S.; Brown, K.; Kim, B.; Lee, P.; Austin, K.; Byrne, C.; Whitehead, L.; Koh, C. Long-term survival and quality of life in patients more than 10 years after pelvic exenteration. Br. J. Surg. 2025, 112, znaf123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cirimbei, C.; Rotaru, V.; Chitoran, E.; Cirimbei, S. Laparoscopic Approach in Abdominal Oncologic Pathology. In Proceedings of the 35th Balkan Medical Week, Athens, Greece, 25–27 September 2018; pp. 260–265. Available online: https://www.webofscience.com/wos/woscc/full-record/WOS:000471903700043 (accessed on 20 July 2023).

- Rotaru, V.; Chitoran, E.; Cirimbei, C.; Cirimbei, S.; Simion, L. Preservation of Sensory Nerves During Axillary Lymphadenectomy. In Proceedings of the 35th Balkan Medical Week, Athens, Greece, 25–27 September 2018; pp. 271–276. Available online: https://www.webofscience.com/wos/woscc/full-record/WOS:000471903700045 (accessed on 20 July 2023).

- Napoletano, G.; De Paola, L.; Circosta, F.; Vergallo, G.M. Right to be forgotten: European instruments to protect the rights of cancer survivors. Acta Biomed. 2024, 95, e2024114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radwan, R.W.; Codd, R.J.; Wright, M.; Fitzsimmons, D.; Evans, M.D.; Davies, M.; Harris, D.A.; Beynon, J. Quality-of-life outcomes following pelvic exenteration for primary rectal cancer. Br. J. Surg. 2015, 102, 1574–1580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roos, E.J.; De Graeff, A.; Van Eijkeren, M.A.; Boon, T.A.; Heintz, A.P.M. Quality of life after pelvic exenteration. Gynecol. Oncol. 2004, 93, 610–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, A.M.; Albizu-Jacob, A.; Fenech, A.L.; Chon, H.S.; Wenham, R.M.; Donovan, K.A. Quality of life after pelvic exenteration for gynecologic cancer: Findings from a qualitative study. Psychooncology 2018, 27, 2357–2362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Dell, M.M.; Steffens, D.; White, K.; Johnstone, C.S.H.; Solomon, M.J.; Brown, K.G.M.; Koh, C.E. Patient Experiences of Long-term Pain and Pain Management Following Pelvic Exenteration for Locally Recurrent Rectal Cancer: A Qualitative Study. Dis. Colon Rectum 2025, 68, 209–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ashraf, B.; Saaiq, M.; Uz-Zaman, K. Qualitative study of nocebo phenomenon (NP) involved in doctor-patient communication. Int. J. Health Policy Manag. 2014, 3, 23–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agozzino, E.; Borrelli, S.; Cancellieri, M.; Carfora, F.M.; Di Lorenzo, T.; Attena, F. Does written informed consent adequately inform surgical patients? A cross sectional study. BMC Med. Ethics 2019, 20, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turillazzi, E.; Neri, M. Informed consent and Italian physicians: Change course or abandon ship-from formal authorization to a culture of sharing. Med. Health Care Philos. 2015, 18, 449–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Ochieng, J.; Buwembo, W.; Munabi, I.; Ibingira, C.; Kiryowa, H.; Nzarubara, G.; Mwaka, E. Informed consent in clinical practice: Patients’ experiences and perspectives following surgery. BMC Res. Notes 2015, 8, 765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez, A.; Filleron, T.; Rouanet, P.; Méeus, P.; Lambaudie, E.; Classe, J.M.; Foucher, F.; Narducci, F.; Gouy, S.; Ferron, G.; et al. Prospective Assessment of First-Year Quality of Life After Pelvic Exenteration for Gynecologic Malignancy: A French Multicentric Study. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2018, 25, 535–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grassi, L.; Caruso, R.; Nanni, M.G. Somatization and somatic symptom presentation in cancer: A neglected area. Int. Rev. Psychiatry 2013, 25, 41–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forsythe, L.P.; Kent, E.E.; Weaver, K.E.; Buchanan, N.; Hawkins, N.A.; Rodriguez, J.L.; Ryerson, A.B.; Rowland, J.H. Receipt of psychosocial care among cancer survivors in the United States. J. Clin. Oncol. 2013, 31, 1961–1969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harji, D.P.; Williams, A.; McKigney, N.; Boissieras, L.; Denost, Q.; Fearnhead, N.S.; Jenkins, J.T.; Griffiths, B. Utilising quality of life outcome trajectories to aid patient decision making in pelvic exenteration. Eur. J. Surg. Oncol. 2022, 48, 2238–2249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cibula, D.; Lednický, S.; Höschlová, E.; Sláma, J.; Wiesnerová, M.; Mitáš, P.; Matějovský, Z.; Schneiderová, M.; Dundr, P.; Borčinová, M.; et al. Quality of life after extended pelvic exenterations. Gynecol. Oncol. 2022, 166, 100–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Denys, A.; Thielemans, S.; Salihi, R.; Tummers, P.; van Ramshorst, G.H. Quality of Life After Extended Pelvic Surgery with Neurovascular or Bony Resections in Gynecological Oncology: A Systematic Review. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2024, 31, 3280–3299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazi, M.; Choubey, K.; Patil, P.; Jaiswal, D.; Ajmera, S.; Desouza, A.; Saklani, A. Patient reported outcomes after multivisceral resection for advanced rectal cancers in female patients. J. Surg. Oncol. 2024, 129, 1106–1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harji, D.P.; Griffiths, B.; Velikova, G.; Sagar, P.M.; Brown, J. Systematic review of health-related quality of life in patients undergoing pelvic exenteration. Eur. J. Surg. Oncol. 2016, 42, 1132–1145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makker, P.G.S.; Koh, C.E.; Solomon, M.; El-Hayek, J.; Kim, B.; Steffens, D. The influence of postoperative morbidity on long-term quality of life outcomes following pelvic exenteration. Eur. J. Surg. Oncol. 2024, 50, 108640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gleeson, N.; Baile, W.; Roberts, W.S.; Hoffman, M.; Fiorica, J.V.; Barton, D.; Cavanagh, D. Surgical and psychosexual outcome following vaginal reconstruction with pelvic exenteration. Eur. J. Gynaecol. Oncol. 1994, 15, 89–95. [Google Scholar]

- Andersen, B.L.; Hacker, N.F. Psychosexual adjustment following pelvic exenteration. Obstet. Gynecol. 1983, 61, 331–338. [Google Scholar]

- Denys, A.; van Nieuwenhove, Y.; Van de Putte, D.; Pape, E.; Pattyn, P.; Ceelen, W.; van Ramshorst, G.H. Patient-reported outcomes after pelvic exenteration for colorectal cancer: A systematic review. Color. Dis. 2022, 24, 353–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, X.; Haiyang, Z. Patient-reported outcomes in Chinese patients with locally advanced or recurrent colorectal cancer after pelvic exenteration. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2024, 31, 7783–7795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dempsey, G.M.; Buchsbaum, H.J.; Morrison, J. Psychosocial adjustment to pelvic exenteration. Gynecol. Oncol. 1975, 3, 325–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vera, M.I. Quality of life following pelvic exenteration. Gynecol. Oncol. 1981, 12, 355–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corney, R.H.; Crowther, M.E.; Everett, H.; Howells, A.; Shepherd, J.H. Psychosexual dysfunction in women with gynaecological cancer following radical pelvic surgery. BJOG 1993, 100, 73–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, J.; Chi, D.S.; Abu-Rustum, N.; Brown, C.L.; McCreath, W.; Barakat, R. Brief report: Total pelvic exenteration—A retrospective clinical needs assessment. Psycho-Oncology 2004, 13, 125–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forner, D.M.; Lampe, B. Ileal Conduit and Continent Ileocecal Pouch for Patients Undergoing Pelvic Exenteration: Comparison of Complications and Quality of Life. Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer 2011, 21, 403–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Austin, K.K.S.; Young, J.M.; Solomon, M.J. Quality of life of survivors after pelvic exenteration for rectal cancer. Dis. Colon Rectum 2010, 53, 1121–1126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, L.N.; Lin, S.E.; Luo, H.L.; Chang, J.C.; Chiang, P.H. Double-barreled Colon Conduit and Colostomy for Simultaneous Urinary and Fecal Diversions: Long-term Follow-up. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2014, 21, 522–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Løve, U.S.; Sjøgren, P.; Rasmussen, P.; Laurberg, S.; Christensen, H.K. Sexual dysfunction after colpectomy and vaginal reconstruction with a vertical rectus abdominis myocutaneous flap. Dis. Colon Rectum 2013, 56, 186–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezk, Y.A.; Hurley, K.E.; Carter, J.; Dao, F.; Bochner, B.H.; Aubey, J.J.; Caceres, A.; Einstein, M.H.; Abu-Rustum, N.R.; Chi, D.S.; et al. A prospective study of quality of life in patients undergoing pelvic exenteration: Interim results. Gynecol. Oncol. 2013, 128, 191–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guimarães, G.C.; Baiocchi, G.; Ferreira, F.O.; Kumagai, L.Y.; Fallopa, C.C.; Aguiar, S.; Rossi, B.M.; Soares, F.A.; Lopes, A. Palliative pelvic exenteration for patients with gynecological malignancies. Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 2011, 283, 1107–1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawighorst, S.; Schoenefuss, G.; Fusshoeller, C.; Franz, C.; Seufert, R.; Kelleher, D.K.; Vaupel, P.; Knapstein, P.G.; Koelbl, H. The physician–patient relationship before cancer treatment: A prospective longitudinal study. Gynecol. Oncol. 2004, 94, 93–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirhashemi, R.; Averette, H.E.; Lambrou, N.; Penalver, M.A.; Mendez, L.; Ghurani, G.; Salom, E. Vaginal Reconstruction at the Time of Pelvic Exenteration: A Surgical and Psychosexual Analysis of Techniques. Gynecol. Oncol. 2002, 87, 39–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawighorst-Knapstein, S.; Schönefuß, G.; Hoffmann, S.O.; Knapstein, P.G. Pelvic Exenteration: Effects of Surgery on Quality of Life and Body Image—A Prospective Longitudinal Study. Gynecol. Oncol. 1997, 66, 495–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woodhouse, C.R.J.; Plail, R.O.; Schlesinger, P.E.; Shepherd, J.E.; Hendry, W.F.; Breach, N.M. Exenteration as palliation for patients with advanced pelvic malignancy. Br. J. Urol. 1995, 76, 315–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brophy, P.F.; Hoffman, J.P.; Eisenberg, B.L. The role of palliative pelvic exenteration. Am. J. Surg. 1994, 167, 386–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kato, K.; Tate, S.; Nishikimi, K.; Shozu, M. Bladder function after modified posterior exenteration for primary gynecological cancer. Gynecol. Oncol. 2013, 129, 229–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wells, G.A. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for Assessing the Quality of Nonrandomised Studies in Meta-Analyses. Available online: https://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/nosgen.pdf (accessed on 22 June 2024).

- Supplemental Handbook Guidance|Cochrane Qualitative and Implementation. Available online: https://methods.cochrane.org/qi/supplemental-handbook-guidance (accessed on 23 June 2024).

- Steffens, D.; Blake, J.; Solomon, M.J.; Lee, P.; Austin, K.K.S.; Byrne, C.M.; Koh, C.E. Trajectories of Quality of Life After Pelvic Exenteration: A Latent Class Growth Analysis. Dis. Colon Rectum 2024, 67, 531–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali Uraiqat, A.; Al Nsour, D.; Mestareehy, K.M.; Allababdeh, M.S.; Naffa, M.T.F.; Alrabee, M.M.; Al-Hammouri, F. Curative pelvic exenteration: Initial experience and clinical outcome. PAMJ 2023, 44, 170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez, M.J.; Barrios, L. Evolution of Pelvic Exenteration. Surg. Oncol. Clin. N. Am. 2005, 14, 587–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karmaniolou, I.; Arkadopoulos, N.; Vassiliou, P.; Nastos, C.; Dellaportas, D.; Siatelis, A.; Theodosopoulos, T.; Vezakis, A.; Parasyris, S.; Smyrniotis, V.; et al. Pelvic Exenteration Put into Therapeutical and Palliative Perspective: It Is Worth to Try. Indian J. Surg. Oncol. 2018, 9, 552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawighorst-Knapstein, S.; Fusshoeller, C.; Franz, C.; Trautmann, K.; Schmidt, M.; Pilch, H.; Schoenefuss, G.; Knapstein, P.G.; Koelbl, H.; Vaupel, P. The impact of treatment for genital cancer on quality of life and body image—Results of a prospective longitudinal 10-year study. Gynecol. Oncol. 2004, 94, 398–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanton, A.L. What happens now? Psychosocial care for cancer survivors after medical treatment completion. J. Clin. Oncol. 2012, 30, 1215–1220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nipp, R.D.; El-Jawahri, A.; Fishbein, J.N.; Eusebio, J.; Stagl, J.M.; Gallagher, E.R.; Park, E.R.; Jackson, V.A.; Pirl, W.F.; Temel, J.S.; et al. The relationship between coping strategies, quality of life, and mood in patients with incurable cancer. Cancer 2016, 122, 2110–2116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bultz, B.D.; Carlson, L.E. Emotional distress: The sixth vital sign—Future directions in cancer care. Psychooncology 2006, 15, 93–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caruso, R.; Nanni, M.G.; Riba, M.B.; Sabato, S.; Grassi, L. The burden of psychosocial morbidity related to cancer: Patient and family issues. Int. Rev. Psychiatry 2017, 29, 389–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grassi, L.; Spiegel, D.; Riba, M. Advancing psychosocial care in cancer patients. F1000Research 2017, 6, 2083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harji, D.P.; Koh, C.; McKigney, N.; Solomon, M.J.; Griffiths, B.; Evans, M.; Heriot, A.; Sagar, P.M.; Velikova, G.; Brown, J.M. Development and validation of a patient reported outcome measure for health-related quality of life for locally recurrent rectal cancer: A multicentre, three-phase, mixed-methods, cohort study. eClinicalMedicine 2023, 17, 101945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, K.; Solomon, M.; Ng, K.S.; Sutton, P.; Koh, C.; White, K.; Steffens, D. Development of a risk prediction tool for patients with locally advanced and recurrent rectal cancer undergoing pelvic exenteration: Protocol for a mixed-methods study. BMJ Open 2023, 13, e075304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burns, E.M.; Quyn, A.; Al Kadhi, O.; Angelopoulos, G.; Armitage, J.; Baker, R.; Barton, D.; Beekharry, R.; Beggs, A.; Yano, H.; et al. The ‘Pelvic exenteration lexicon’: Creating a common language for complex pelvic cancer surgery. Color. Dis. 2023, 25, 888–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Study | Study Population | Study Design | Method of QoL Evaluation | Summary of Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dempsey (1975) [34] | N = 16 gynecological cancers | Qualitative, Prospective | Qualitative interview | QoL and adaptation outcomes discussed |

| Vera (1981) [35] | N = 19 gynecological cancers | Qualitative, Retrospective | Qualitative interview | ↓ Sexual function |

| Corney (1993) [36] | N = 8 gynecological cancers | Qualitative, Retrospective | Qualitative interview | ↓ Sexual function |

| Carter (2004) [37] | N = 6 gynecological cancers | Qualitative, Retrospective | Qualitative interview | ↓ Body image |

| Nelson (2021) [15] | N = 14 pelvic cancers | Qualitative, Prospective | Semi-structured interviews | ↓ Sexual function |

| O’Dell (2023) [16] | N = 18 pelvic cancers | Qualitative, Prospective | Thematic analysis of patient interviews | Psychological distress |

| Forner (2011) [38] | N = 100 gynecological cancers | Quantitative, Retrospective | SF12 | ↓ Sexual function |

| Austin (2010) [39] | N = 37 CRC | Quantitative, Retrospective, case-controlled, cross-sectional | FACT-C SF36 | ↓ Overall QoL |

| Roos (2004) [14] | N = 32 gynecological cancers | Quantitative, Prospective | EORTC QLQ-C30 EORTC QLQ-OV28 | ↓ Overall QoL |

| Hsu (2014) [40] | N = 18 NS cancers | Quantitative, Retrospective, case-controlled | EORTC QLQ-C30 | Persistent pain |

| Love (2013) [41] | N = 26 NS cancers | Retrospective | Sexual function questionnaire | Fatigue |

| Rezk (2012) [42] | N = 16 gynecological cancers | Quantitative, Prospective | EORTC QLQ-C30 EORTC-QLQ CR38, EORTC QLQBLM30 BFI, BPI-SF, IADL, CES-D, IES-R | ↓ Overall QoL |

| Guimaraes (2011) [43] | N = 13 gynecological cancers | Quantitative, Retrospective | Unspecified symptoms scale | ↓ Urinary function |

| Zoucas (2010) [3] | N = 85 CRC and gynecological cancers | Quantitative, Prospective | EORTC QLQ-C30 | ↓ Sexual function |

| Hawighorst (2004) [44] | N = 129 gynecological cancers undergoing PE (62 patients) or Wertheim procedure (67 patients) | Quantitative, Prospective | CARES, Preoperative Anxiety Scale | ↓ Overall QoL |

| Mirhashemi (2002) [45] | N = 9 gynecological cancers | Quantitative, Retrospective | Symptoms scale | Persistent pain |

| Hawighorst-Knapstein (1997) [46] | N = 28 gynecological cancers | Quantitative, Prospective longitudinal | EORTC QLQ-C30, BIQ, CARES, Strauss—Appelt Body Image Score | ↓ Overall QoL |

| Woodhouse (1995) [47] | N = 10, NS cancers | Quantitative, Retrospective | Symptoms scale | Psychological distress |

| Brophy (1994) [48] | N = 35, pelvic cancers | Quantitative, Retrospective | Symptoms scale | ↓ Sexual function |

| Gleeson (1994) [30] | N = 14 patients with vaginal reconstruction after PE | Quantitative, Retrospective | Custom psychosexual questionnaire, semi-structured interviews | Stoma-related distress |

| Andersen (1983) [31] | N = 15 gynecological cancer | Quantitative, Retrospective | Sexual and psychosexual assessment though semi-structured interviews SCL90, BDI, KAS-R, MAT, DSFI, HTH, SAI | ↓ Overall QoL |

| Radwan (2015) [13] | N = 110, CRC | Quantitative, Prospective | EORTC QLQ-C30 | QoL and adaptation outcomes discussed |

| Young (2014) [2] | N = 182, CRC | Quantitative, Prospective | FACT-C, SF36, AuQoL, DT | Persistent pain |

| Beaton (2014) [7] | N = 31, CRC | Quantitative, Retrospective | FACT-C | ↓ Overall QoL |

| Kato (2013) [49] | N = 49, gynecological cancer | Quantitative, Retrospective | UDI-6 | ↓ Sexual function |

| Alahmadi (2021) [6] | N = 710 patients post-PE | Quantitative, Retrospective | EORTC QLQ-C30 | Persistent pain |

| Martinez (2018) [21] | N = 97 pelvic cancers | Quantitative, Prospective, Multicenter | EORTC QLQ-C30 | Psychological distress |

| Dessole (2018) [5] | N = 96 recurrent gynecologic cancer | Quantitative, Prospective, Multicenter | EORTC QLQ-C30, DSFI | ↓ Sexual function |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rotaru, V.; Chitoran, E.; Gelal, A.; Gullo, G.; Stefan, D.-C.; Simion, L. Living After Pelvic Exenteration: A Mixed-Methods Synthesis of Quality-of-Life Outcomes and Patient Perspectives. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 6541. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14186541

Rotaru V, Chitoran E, Gelal A, Gullo G, Stefan D-C, Simion L. Living After Pelvic Exenteration: A Mixed-Methods Synthesis of Quality-of-Life Outcomes and Patient Perspectives. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(18):6541. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14186541

Chicago/Turabian StyleRotaru, Vlad, Elena Chitoran, Aisa Gelal, Giuseppe Gullo, Daniela-Cristina Stefan, and Laurentiu Simion. 2025. "Living After Pelvic Exenteration: A Mixed-Methods Synthesis of Quality-of-Life Outcomes and Patient Perspectives" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 18: 6541. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14186541

APA StyleRotaru, V., Chitoran, E., Gelal, A., Gullo, G., Stefan, D.-C., & Simion, L. (2025). Living After Pelvic Exenteration: A Mixed-Methods Synthesis of Quality-of-Life Outcomes and Patient Perspectives. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(18), 6541. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14186541