Comparative Efficacy and Cost-Effectiveness of Denosumab Versus Zoledronic Acid in Cancer Patients with Bone Metastases

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Patient Population

2.3. Efficacy and Safety Measures

2.4. Ethical Considerations

2.5. Statistical Analysis

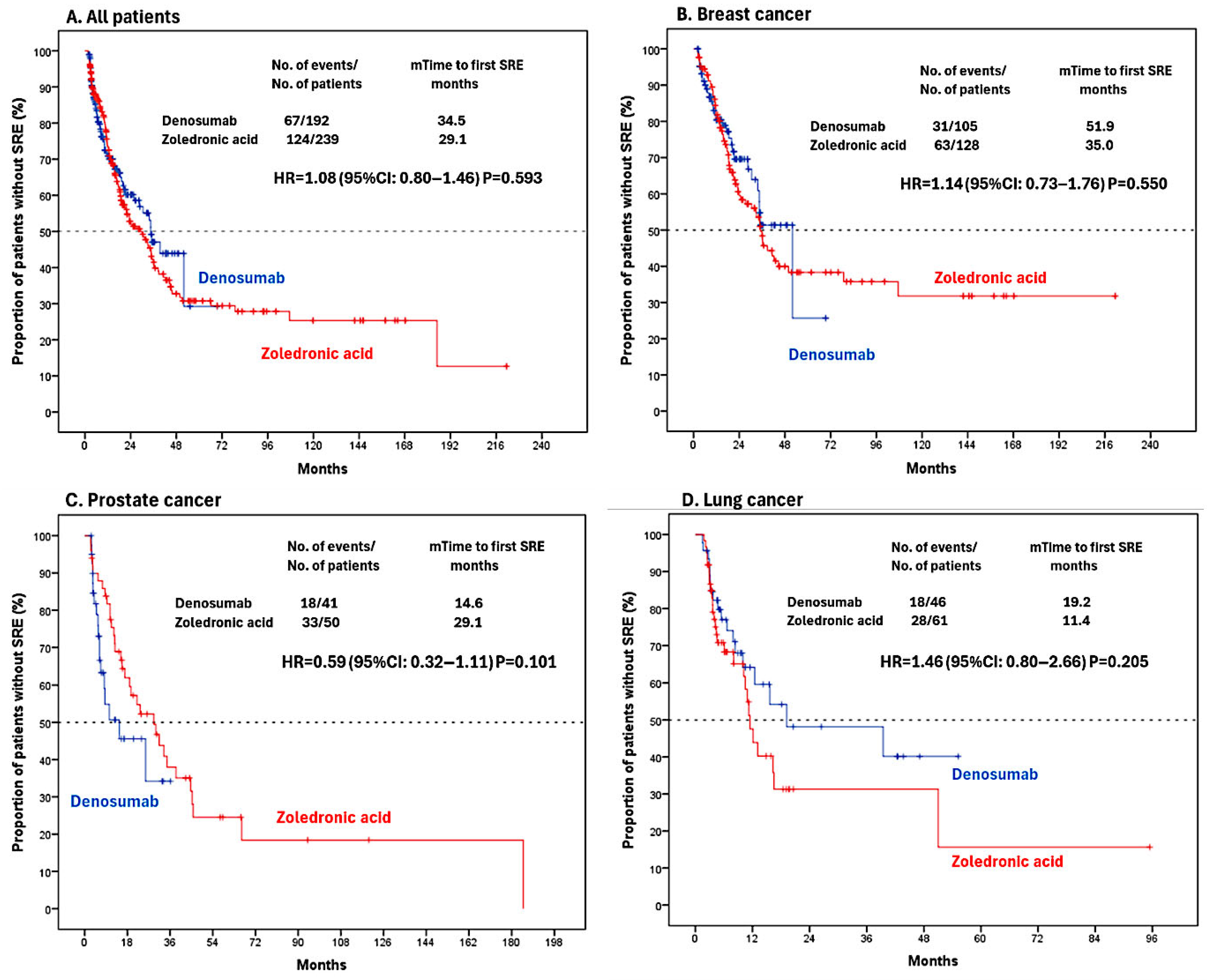

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of Patients

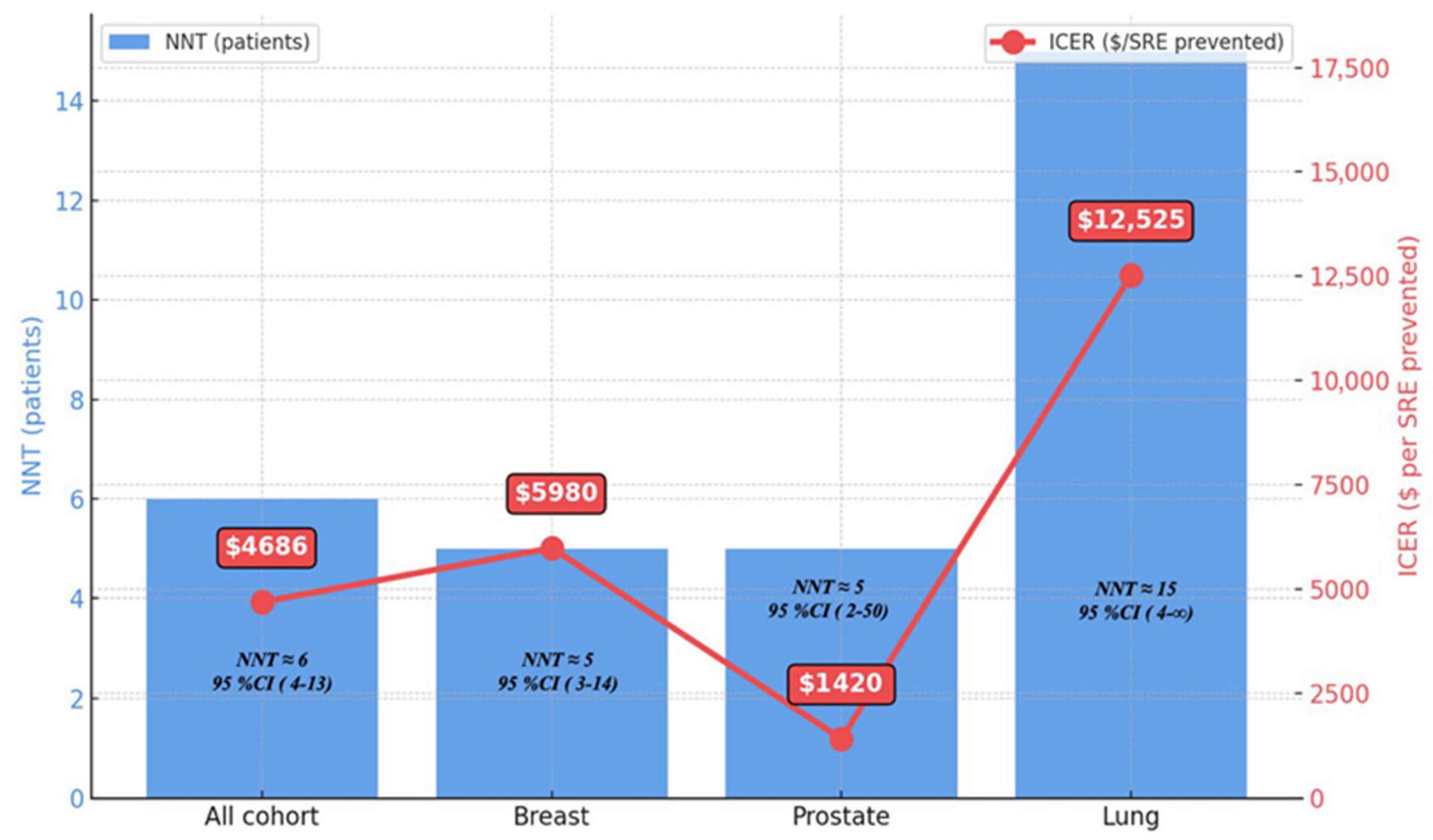

3.2. Number Needed to Treat Analysis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mundy, G. Metastasis to bone: Causes, consequences and therapeutic opportunities. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2002, 2, 584–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipton, A.; Small, E.; Saad, F.; Gleason, D.; Gordon, D.; Smith, M.; Rosen, L.; Kowalski, M.O.; Reitsma, D.; Seaman, J. The new bisphosphonate, Zometa® (Zoledronic Acid), decreases skeletal complications in both osteolytic and osteoblastic lesions: A comparison to pamidronate. Cancer Investig. 2002, 20, 45–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coleman, R.E. Clinical features of metastatic bone disease and risk of skeletal morbidity. Clin. Cancer Res. 2006, 12, 6243s–6249s. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, M.; Bell, R.; Bourgeois, H.; Brufsky, A.; Diel, I.; Eniu, A.; Fallowfield, L.; Fujiwara, Y.; Jassem, J.; Paterson, A.H.; et al. Bone-Related complications and quality of life in advanced breast cancer: Results from a randomized phase iii trial of denosumab versus zoledronic acid. Clin. Cancer Res. 2012, 18, 4841–4849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stopeck, A.T.; Lipton, A.; Body, J.-J.; Steger, G.G.; Tonkin, K.; de Boer, R.H.; Lichinitser, M.; Fujiwara, Y.; Yardley, D.A.; Viniegra, M.; et al. Denosumab compared with Zoledronic Acid for the treatment of bone metastases in patients with advanced breast cancer: A randomized, double-blind study. J. Clin. Oncol. 2010, 28, 5132–5139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fizazi, K.; Carducci, M.; Smith, M.; Damião, R.; Brown, J.; Karsh, L.; Milecki, P.; Shore, N.; Rader, M.; Wang, H.; et al. Denosumab versus zoledronic acid for treatment of bone metastases in men with castration-resistant prostate cancer: A randomised, double-blind study. Lancet 2011, 377, 813–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henry, D.H.; Costa, L.; Goldwasser, F.; Hirsh, V.; Hungria, V.; Prausova, J.; Scagliotti, G.V.; Sleeboom, H.; Spencer, A.; Vadhan-Raj, S.; et al. Randomized, double-blind study of denosumab versus zoledronic acid in the treatment of bone metastases in patients with advanced cancer (excluding breast and prostate cancer) or multiple myeloma. J. Clin. Oncol. 2011, 29, 1125–1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, M.R.; Saad, F.; Coleman, R.; Shore, N.; Fizazi, K.; Tombal, B.; Miller, K.; Uemura, H.; Ye, D.; Ng, S.; et al. Denosumab for prevention of skeletal-related events in metastatic prostate cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2021, 384, 776–787. [Google Scholar]

- Fizazi, K.; Lipton, A.; Body, J.J.; Coleman, R.; Tonkin, K.; de Boer, R.; Berardi, R.; Stopeck, A.; Yardley, D.; Henry, D.; et al. Denosumab versus zoledronic acid in metastatic breast cancer. Lancet Oncol. 2022, 23, e200–e210. [Google Scholar]

- Lipton, A.; Fizazi, K.; Stopeck, A.; Henry, D.; Yardley, D.; Costa, L.; Brown, J.; Smith, M.; Saad, F.; Body, J.J.; et al. Comparative safety analysis of denosumab versus zoledronic acid. J. Clin. Oncol. 2022, 40, 1650–1660. [Google Scholar]

- Coleman, R.; Costa, L.; Stopeck, A.; Body, J.J.; Smith, M.; Brown, J.; Gralow, J.; Lipton, A.; Saad, F.; Berardi, R.; et al. Bone-targeted agents in metastatic cancer: ESMO consensus guidelines. Ann. Oncol. 2023, 34, 123–135. [Google Scholar]

- Costa, L.; Coleman, R.; Fizazi, K.; Lipton, A.; Smith, M.; Henry, D.; Stopeck, A.; Yardley, D.; Brown, J.; Saad, F.; et al. Cost-effectiveness analysis of bone-targeting agents in solid tumors. JAMA Oncol. 2023, 9, 412–420. [Google Scholar]

- Block, G.A.; Bone, H.G.; Fang, L.; Lee, E.; Padhi, D. Renal safety of denosumab in patients with renal impairment: A pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic study. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2012, 27, 1471–1479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arellano, J.; Qian, Y.; Zhao, Z.; Oppenheimer, L.; Pan, F. Cost-effectiveness of denosumab versus zoledronic acid in the prevention of skeletal-related events in patients with bone metastases from solid tumors in the United States. J. Med. Econ. 2014, 17, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Saad, F.; Brown, J.E.; Van Poznak, C.; Ibrahim, T.; Stemmer, S.M.; Stopeck, A.; Diel, I.; Takahashi, S.; Shore, N.; Henry, D.; et al. Incidence, risk factors, and outcomes of osteonecrosis of the jaw: Integrated analysis from three blinded active-controlled phase III trials in cancer patients with bone metastases. Ann. Oncol. 2012, 23, 1341–1347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, C.; Fizazi, K.; Heidenreich, A.; Ost, P.; Procopio, G.; Tombal, B.; Gillessen, S.; Shore, N.; James, N.; Suzuki, H.; et al. Prostate cancer: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann. Oncol. 2020, 31, 1119–1134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freites-Martínez, A.; Arias-Santiago, S.; Viera, A.; Szabo, E.; Cañueto, J.; Palamaras, I.; Ocampo, C.; Gómez, M.; Vázquez, R.; Rodríguez, M.; et al. CTCAE versión 5.0. Evaluación de la gravedad de los eventos adversos dermatológicos de las terapias antineoplásicas. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2021, 112, 90–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipton, A.; Fizazi, K.; Stopeck, A.; Henry, D.; Brown, J.; Yardley, D.; Costa, L.; Body, J.J.; Saad, F.; Smith, M.; et al. Superiority of denosumab to zoledronic acid for prevention of skeletal-related events: A combined analysis of three pivotal, randomised, phase 3 trials. Eur. J. Cancer 2012, 48, 3082–3092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scagliotti, G.V.; Hirsh, V.; Siena, S.; Henry, D.H.; Woll, P.J.; Manegold, C.; Zhang, L.; Zheng, M.; Jacobs, I.; Wu, Y.; et al. Denosumab versus zoledronic acid for treatment of bone metastases in men with lung cancer: A randomized, double-blind study. J. Thorac. Oncol. 2019, 14, 837–845. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, S.; Liao, Y. Efficacy and safety of denosumab versus zoledronic acid in patients with bone metastases: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Am. J. Clin. Oncol. 2013, 36, 399–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ford, R.; Elders, A.; Mulatero, C.; Royle, P.; Sharma, P.; Stewart, F.; Todd, R.; Mowatt, G.; Vale, L.; Witham, M.; et al. Denosumab for treatment of bone metastases secondary to solid tumours: Systematic review and network meta-analysis. Eur. J. Cancer 2013, 49, 416–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Liu, X.; Wen, X.; Li, H.; Li, W.J. Meta-analysis of clinical trials to assess denosumab over zoledronic acid in bone metastasis. Int. J. Clin. Pharm. 2021, 43, 2–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, B.; Lin, F.X.; Xie, D.; Hu, Q.X.; Yu, G.Y.; Du, S.X.; Li, X.D.; Wang, X.; Chen, J.; Zhao, H.; et al. Meta-analysis comparing denosumab and zoledronic acid for treatment of bone metastases in patients with advanced solid tumours. Eur. J. Cancer Care 2017, 26, e12541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wadhwa, N.; Dixit, J.; Malhotra, P.; Lakshmi, P.V.M.; Prinja, S.R. Cost-effectiveness analysis of denosumab in the prevention of skeletal-related events among patients with breast cancer with bone metastasis in India. JCO Glob. Oncol. 2024, 10, e2300396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yfantopoulos, A.; Chatzikou, M.; Fishman, P.; Chatzaras, A.J. The importance of economic evaluation in healthcare decision-making—A case of denosumab versus zoledronic acid from Greece. Third-party payer perspective. Oncol 2013, 4, 25–31. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, M.; Sorg, R.; Wu, E.Q.; Namjoshi, M.J. Cost-effectiveness of denosumab compared with zoledronic acid in patients with breast cancer and bone metastases. Clin. Breast Cancer 2012, 12, 247–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, M.; Wu, E.Q.; Parikh, K.; Diener, M.; Yu, A.P.; Guo, A.; Culver, K.W.J.; Qin, A.; Zhao, Y.; Johnston, S.; et al. Economic evaluation of denosumab compared with zoledronic acid in hormone-refractory prostate cancer patients with bone metastases. J. Manag. Care Pharm. 2011, 17, 621–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snedecor, J.A.; Kaura, S.; Botteman, M.F.; Stephens, J.M. Cost-effectiveness of denosumab versus zoledronic acid in the management of skeletal metastases secondary to breast cancer. Clin. Ther. 2012, 34, 1334–1349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snedecor, J.A.; Kaura, S.; Botteman, M.F.; Stephens, J.M. Denosumab versus zoledronic acid for treatment of bone metastases in men with castration-resistant prostate cancer: A cost-effectiveness analysis. J. Med. Econ. 2013, 16, 19–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Body, J.J.; Lipton, A.; Gralow, J.; Steger, G.G.; Gao, G.; Yeh, H.; Fizazi, K.; Henry, D.H.; Stopeck, A.; Fan, M.; et al. A phase III trial of denosumab compared with zoledronic acid in patients with bone metastases from advanced cancer. Eur. J. Cancer 2015, 51, 1467–1475. [Google Scholar]

- Stopeck, A.; Rader, M.; Henry, D.; Costa, L.; Body, J.J.; Lipton, A.; Coleman, R.; Fizazi, K.; Smith, M.; Saad, F.; et al. Cost-effectiveness of denosumab vs zoledronic acid for prevention of skeletal-related events in patients with solid tumors and bone metastases in the United States. J. Med. Econ. 2012, 15, 712–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Big Molecule Watch. EMA issues positive CHMP opinions for Fresenius denosumab biosimilars. 27 May 2025. Available online: https://www.bigmoleculewatch.com/2025/06/02/ema-issues-positive-chmp-opinions-for-fresenius-denosumab-biosimilars/ (accessed on 5 August 2025).

- Saad, A.F. Zoledronic acid is effective in preventing and delaying skeletal events in patients with bone metastases secondary to genitourinary cancers. BJU Int. 2005, 96, 964–969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosen, L.; Tchekmedyian, S.; Yanagihara, R.; Hirsh, V.; Krzakowski, M.; Pawlicki, M.; e Souza, P.; Zheng, M.; Urbanowitz, G.; Sgouros, J.; et al. Zoledronic acid versus placebo in the treatment of skeletal metastases in patients with lung cancer and other solid tumors: A phase III, double-blind, randomized trial—The Zoledronic Acid Lung Cancer and Other Solid Tumors Study Group. J. Clin. Oncol. 2003, 21, 3150–3157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coleman, R.; Brown, J.E.; Rathbone, E. Management of cancer treatment-induced bone loss. Nat. Rev. Rheumatol. 2013, 9, 365–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anastasilakis, A.D.; Polyzos, S.A.; Makras, P. Denosumab discontinuation and the rebound phenomenon A narrative review. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | All Patients n = 431 | Denosumab n = 192 | Zoledronic Acid n = 239 | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender-Female n (%) | 262 (60.8) | 121 (63.0) | 141 (59.0) | 0.35 | |

| Tumour type n (%) | 0.94 | ||||

| Breast | 233 (54.1) | 105 (54.7) | 128 (53.6) | ||

| Prostate | 91 (21.1) | 41 (21.4) | 50 (20.9) | ||

| Lung | 107 (24.8) | 46 (24.0) | 61 (25.5) | ||

| Denovo bone metastasis n (%) | 261 (60.6) | 126 (65.6) | 135 (56.5) | 0.12 | |

| ECOG n (%) | 0.41 | ||||

| 0 | 166 (38.5) | 78 (40.6) | 88 (36.8) | ||

| ≥1 | 265 (61.5) | 114 (59.4) | 151 (63.2) | ||

| Previously skeletal event n (%) | 240 (55.7) | 101 (52.6) | 139 (58.2) | 0.27 | |

| Bone fractured | 18 (4.2) | 9 (4.7) | 9 (3.8) | 0.31 | |

| Radiotherapy | 228 (52.9) | 97 (50.5) | 131 (54.8) | ||

| Spinal cord compression | 5 (1.2) | 2 (1.0) | 3 (1.3) | ||

| Bone surgery | 5 (1.2) | 1 (0.5) | 4 (1.7) | ||

| Cranial metastasis n (%) | 103 (23.9) | 38 (19.8) | 65 (27.2) | 0.08 | |

| Visceral metastasis n (%) | 251 (58.2) | 106 (55.2) | 145 (60.7) | 0.28 | |

| Liver | 179 (41.5) | 71 (37.0) | 108 (45.2) | 0.41 | |

| Lung | 47 (10.9) | 24 (12.5) | 23 (9.6) | ||

| Other | 23 (5.3) | 11 (5.7) | 12 (5.0) | ||

| Median (range) | |||||

| Age of diagnosis (years) | 57 (24–88) | 57 (24–88) | 57 (24–83) | 0.33 | |

| Lead-time from diagnosis to MM (month) | 54 (7–233) | 73 (7–199) | 49 (7–233) | 0.44 | |

| Time to treatment initiation (day) | 56 (0–3844) | 65 (0–2506) | 46 (0–3844) | 0.02 | |

| Median duration of follow-up (month) | 46 (6–328) | 37 (6–250) | 56 (6–328) | 0.04 | |

| Variables | SRE (+) | SRE (−) | Univariate | p | Multivariate | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | n (%) | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | ||||

| Age (years) | <65 | 145 (46.9) | 164 (53.1) | Ref. | |||

| ≥65 | 46 (37.7) | 76 (62.3) | 0.6 (0.44–1.05) | 0.08 | |||

| Tumor type | Prostate | 51 (56.0) | 40 (44.0) | Ref. | Ref. | ||

| Other | 140 (41.2) | 200 (58.8) | 1.8(1.1–2.9) | 0.01 | 1.9 (1.22–3.19) | 0.005 | |

| ECOG | 0 | 79 (47.6) | 87 (52.4) | Ref. | |||

| ≥1 | 112 (42.7) | 150 (57.3) | 0.8 (0.54–1.19) | 0.27 | |||

| Prior SRE | No | 97 (38.8) | 153 (61.2) | Ref. | Ref. | ||

| Yes | 94 (55.6) | 75 (44.4) | 1.6 (1.1–2.3) | 0.01 | 1.6 (1.12–2.49) | 0.011 | |

| Visceral Met | No | 86 (37.9) | 141 (62.1) | Ref. | |||

| Yes | 105 (52.2) | 96 (47.8) | 1.2 (0.81–1.77) | 0.34 | |||

| Cranial Met | No | 170 (43.9) | 217 (56.1) | Ref. | |||

| Yes | 21 (46.7) | 24 (53.3) | 1.1 (0.72–1.76) | 0.59 | |||

| Treatment | Denosumab | 85 (44.3) | 107 (55.7) | Ref. | Ref. | ||

| ZA | 106 (44.4) | 133 (55.6) | 2.0 (1.36–2.97) | 0.001 | 2.0 (1.34–2.98) | 0.001 | |

| Cancer Type | Treatment | Median Intervention Months (Range) | p-Value | Mean ± SD Cost | Median Cost $ (Range) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | Denosumab | 11 (2–74) | <0.001 | 1743.4 ± 1507.6 | 1155 (210–7770) | <0.001 |

| Zoledronic Acid | 17 (2–237) | 649.1 ± 830.9 | 374 (44–5214) | |||

| Breast Cancer | Denosumab | 17 (2–74) | 0.002 | 2095.2 ± 1566.3 | 1680 (210–7770) | <0.001 |

| Zoledronic Acid | 22 (2–237) | 831.6 ± 946.3 | 484 (44–5214) | |||

| Prostate Cancer | Denosumab | 7 (3–39) | <0.001 | 1141.8 ± 1003.8 | 735 (315–4095) | 0.002 |

| Zoledronic Acid | 21 (3–191) | 699.5 ± 770.4 | 451 (66–4356) | |||

| Lung Cancer | Denosumab | 9 (2–59) | 0.084 | 1476.5 ± 1545.9 | 945 (210–6195) | <0.001 |

| Zoledronic Acid | 5 (2–102) | 224.9 ± 320.0 | 110 (44–2144) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Aliyev, V.; Guliyev, M.; Günaltılı, M.; Fidan, M.C.; Çerme, E.; Abbasov, H.; Birsin, Z.; Cebeci, S.; Demirci, N.S.; Alan, Ö. Comparative Efficacy and Cost-Effectiveness of Denosumab Versus Zoledronic Acid in Cancer Patients with Bone Metastases. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 6469. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14186469

Aliyev V, Guliyev M, Günaltılı M, Fidan MC, Çerme E, Abbasov H, Birsin Z, Cebeci S, Demirci NS, Alan Ö. Comparative Efficacy and Cost-Effectiveness of Denosumab Versus Zoledronic Acid in Cancer Patients with Bone Metastases. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(18):6469. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14186469

Chicago/Turabian StyleAliyev, Vali, Murad Guliyev, Murat Günaltılı, Mehmet Cem Fidan, Emir Çerme, Hamza Abbasov, Zeliha Birsin, Selin Cebeci, Nebi Serkan Demirci, and Özkan Alan. 2025. "Comparative Efficacy and Cost-Effectiveness of Denosumab Versus Zoledronic Acid in Cancer Patients with Bone Metastases" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 18: 6469. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14186469

APA StyleAliyev, V., Guliyev, M., Günaltılı, M., Fidan, M. C., Çerme, E., Abbasov, H., Birsin, Z., Cebeci, S., Demirci, N. S., & Alan, Ö. (2025). Comparative Efficacy and Cost-Effectiveness of Denosumab Versus Zoledronic Acid in Cancer Patients with Bone Metastases. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(18), 6469. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14186469