Implementation of Evidence-Based Psychological Treatments to Address Depressive Disorders: A Systematic Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

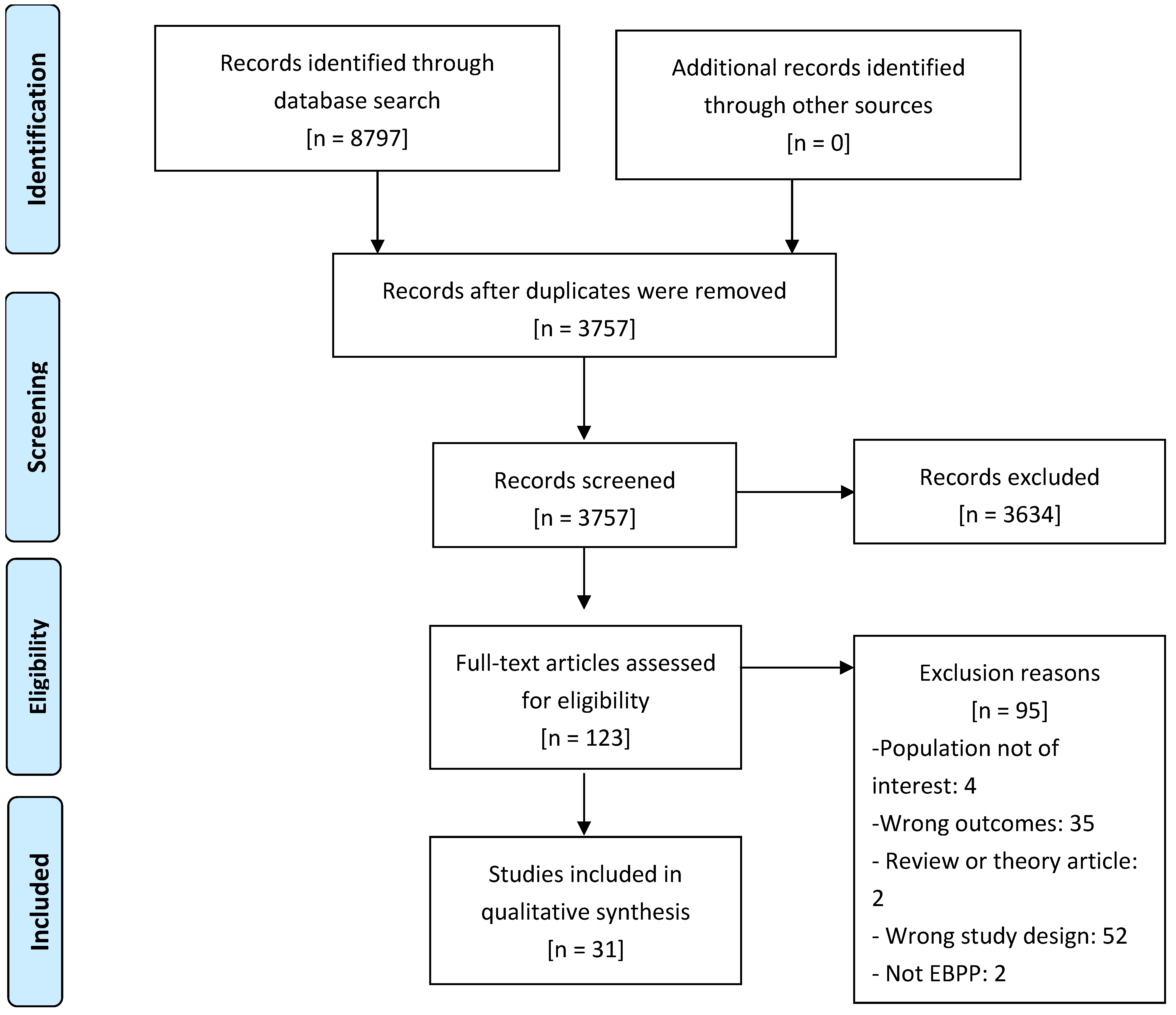

2. Methods

2.1. Searches

2.2. Study Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

2.3. Data Extraction Strategy

2.4. Study Quality Assessment

3. Results

3.1. Review Statistics

3.2. Characteristics of Studies

3.2.1. Research Objective and Units of Analysis

3.2.2. Design

3.2.3. Implementation Outcomes

3.2.4. Characteristics of the Population

3.2.5. Theoretical Framework

3.2.6. Treatment Characteristics

3.2.7. Study Settings

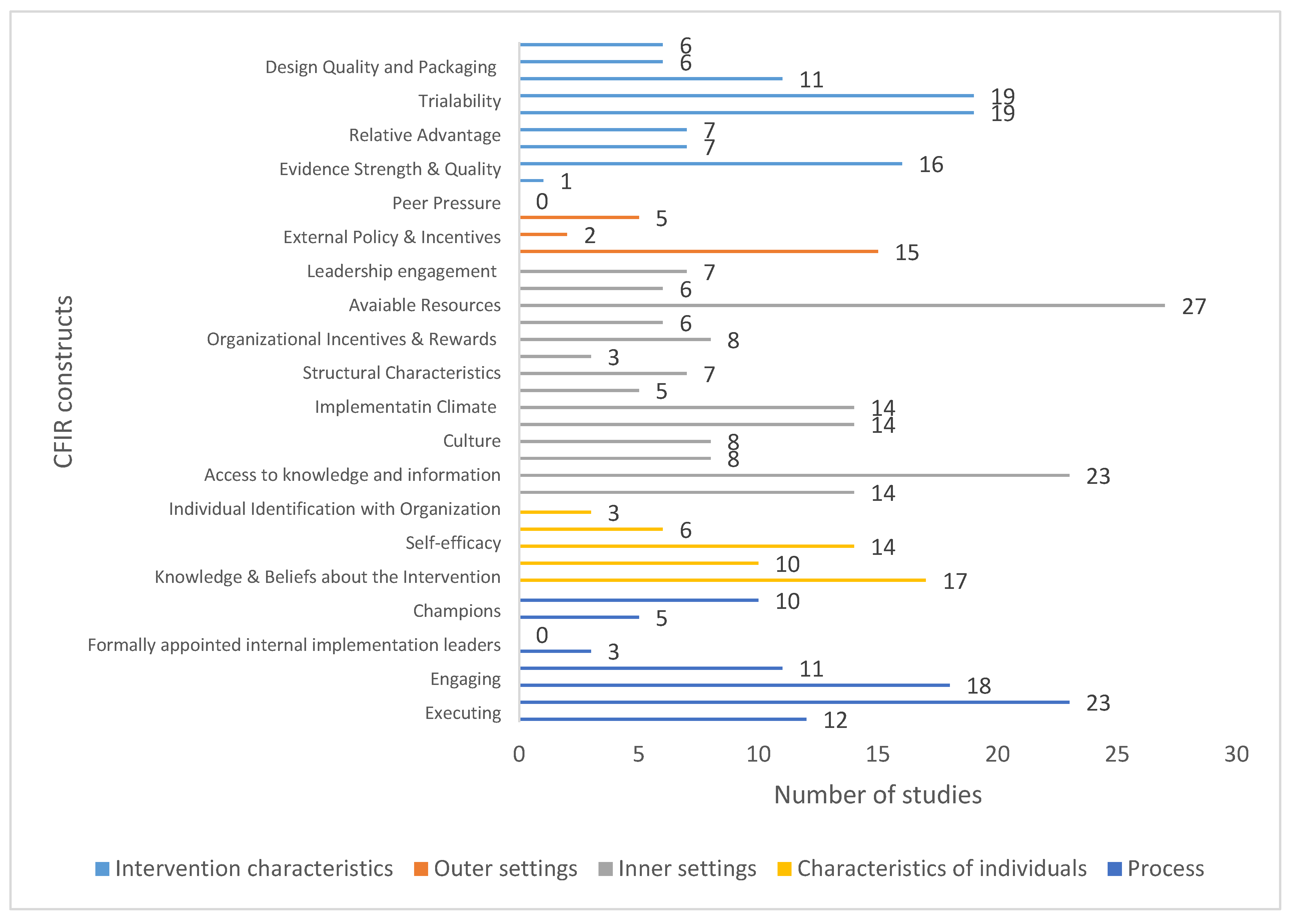

3.3. Qualitative Assessment

4. Discussion

4.1. Strengths and Limitations

4.2. Future Directions

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ARC | Availability, Responsiveness and Continuity |

| BA | Behavioral Activation |

| BDIT | Brief Dynamic Interpersonal Therapy |

| BPS | Brief Psychosocial Support |

| CB | Cognitive Behavioral |

| CBT | Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy |

| CCM | Collaborative Care Management |

| CETA | Common Elements Treatment Approach |

| CFIR | Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research |

| COPE | Creating Opportunities for Personal Empowerment |

| DBT | Dialectical Behavioral Therapy |

| EBPP | Evidence-Based Psychological Practice |

| EPIS | Exploration, Preparation/Adoption, Implementation and Sustainment |

| FOCUS-PDSA | Find, Organize, Clarify, Understand, Select—Plan, Do, Study, Act |

| IPT-AST | IPT-Adolescents Skills Training |

| IPT | Inter-Personal Therapy |

| IQA | Intensive Quality Assurance |

| IR | Implementation Research |

| MF-PEP | Multi-Family Psychoeducational Psychotherapy |

| NICE | National Institute for Health and Care Excellence |

| PARISH | Promoting Action on Research Implementation in Health Services |

| PICO | Participants, Interventions, Comparisons and Outcomes |

| PRISMA | Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses |

| PTSD | Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder |

| RE-AIM | Reach, Effectiveness, Adoption, Implementation, and Maintenance |

| SAM | System Activation Method |

| US | United States |

| VA | Veterans Affairs |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

| YLDs | Years Lived with Disability |

References

- Vos, T.; Lim, S.S.; Abbafati, C.; Abbas, K.M.; Abbasi, M.; Abbasifard, M.; Abbastabar, H.; Abd-Allah, F.; Abdelalim, A.; Abdollahi, M.; et al. Global burden of 369 diseases and injuries in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2019: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet 2020, 396, 1204–1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- GBD 2019 Disease and Injuries Collaborators. Global, regional, and national burden of 12 mental disorders in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2019: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet Psychiatry 2022, 9, 137–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuelke, A.E.; Luck, T.; Schroeter, M.L.; Witte, A.V.; Hinz, A.; Engel, C.; Enzenbach, C.; Zachariae, S.; Loeffler, M.; Thiery, J.; et al. The association between unemployment and depression-Results from the population-based LIFE-adult-study. J. Affect. Disord. 2018, 235, 399–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuijpers, P.; Noma, H.; Karyotaki, E.; Vinkers, C.H.; Cipriani, A.; Furukawa, T.A. A network meta-analysis of the effects of psychotherapies, pharmacotherapies and their combination in the treatment of adult depression. World Psychiatry Off. J. World Psychiatr. Assoc. 2020, 19, 92–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moitra, M.; Santomauro, D.; Collins, P.Y.; Vos, T.; Whiteford, H.; Saxena, S.; Ferrari, A.J.; Hanlon, C. The global gap in treatment coverage for major depressive disorder in 84 countries from 2000–2019: A systematic review and Bayesian meta-regression analysis. Hanlon C, editor. PLoS Med. 2022, 19, e1003901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pakenham-Walsh, N. Learning from one another to bridge the “know-do gap”. Br. Med. J. 2004, 329, 1189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, Z.S.; Wooding, S.; Grant, J. The answer is 17 years, what is the question: Understanding time lags in translational research. J. R. Soc. Med. 2011, 104, 510–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mareeuw, F.v.D.D.; Vaandrager, L.; Klerkx, L.; Naaldenberg, J.; Koelen, M. Beyond bridging the know-do gap: A qualitative study of systemic interaction to foster knowledge exchange in the public health sector in the Netherlands. BMC Public Health 2015, 15, 922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazdin, A.E. Evidence-Based Treatment and Practice: New Opportunities to Bridge Clinical Research and Practice, Enhance the Knowledge Base, and Improve Patient Care. Am. Psychol. 2008, 63, 146–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, E.M.; Smith, A.M.; Jensen-Doss, A. Who’s using treatment manuals? A national survey of practicing therapists. Behav. Res. Ther. 2013, 51, 706–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tackett, J.L.; Brandes, C.M.; King, K.M.; Markon, K.E. Psychology’s Replication Crisis and Clinical Psychological Science. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 2019, 15, 579–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, M.S.; Kirchner, J.A. Implementation science: What is it and why should I care? Psychiatry Res. 2020, 283, 112376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fixsen, D.L.; Naoom, S.; Blase, K.; Friedman, R.; Wallace, F. Implementation Research: A Synthesis of the Literature; The National Implementation Research Network: Tampa, FL, USA, 2005; pp. 23–34. [Google Scholar]

- King, K.M.; Pullmann, M.D.; Lyon, A.R.; Dorsey, S.; Lewis, C.C. Using implementation science to close the gap between the optimal and typical practice of quantitative methods in clinical science. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 2019, 128, 547–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grol, R.P.T.M.; Bosch, M.C.; Hulscher, M.E.J.L.; Eccles, M.P.; Wensing, M. Planning and studying improvement in patient care: The use of theoretical perspectives. Milbank Q. 2007, 85, 93–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babione, J.M. Evidence-based practice in psychology: An ethical framework for graduate education, clinical training, and maintaining professional competence. Ethics Behav. 2010, 20, 443–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damschroder, L.J.; Aron, D.C.; Keith, R.E.; Kirsh, S.R.; Alexander, J.A.; Lowery, J.C. Fostering implementation of health services research findings into practice: A consolidated framework for advancing implementation science. Implement. Sci. 2009, 4, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mchugo, G.; Drake, R.; Whitley, R.; Bond, G.; Campbell, K.; Rapp, C.; Goldman, H.H.; Lutz, W.J.; Finnerty, M.T. Fidelity Outcomes in the National Implementing Evidence-Based Practices Project. Psychiatr. Serv. 2007, 58, 1279–1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nilsen, P.; Birken, S.; Nilsen, P. Overview of theories, models and frameworks in implementation science. In Handbook on Implementation Science; Edward Elgar: Cheltenham, UK, 2020; pp. 8–31. [Google Scholar]

- Kirk, M.A.; Kelley, C.; Yankey, N.; Birken, S.A.; Abadie, B.; Damschroder, L. A systematic review of the use of the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research. Implement. Sci. 2016, 11, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glasgow, R.E.; Harden, S.M.; Gaglio, B.; Rabin, B.; Smith, M.L.; Porter, G.C.; Ory, M.G.; Estabrooks, P.A. RE-AIM planning and evaluation framework: Adapting to new science and practice with a 20-year review. Front. Public Health 2019, 7, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutchinson, A.M.; Wilkinson, J.E.; Kent, B.; Harrison, M.B. Using the Promoting Action on Research Implementation in Health Services Framework to Guide Research Use in the Practice Setting. Worldviews Evid.-Based Nurs. 2012, 9, 59–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moullin, J.C.; Dickson, K.S.; Stadnick, N.A.; Rabin, B.; Aarons, G.A. Systematic review of the Exploration, Preparation, Implementation, Sustainment (EPIS) framework. Implement. Sci. 2019, 14, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powell, B.J.; Waltz, T.J.; Chinman, M.J.; Damschroder, L.J.; Smith, J.L.; Matthieu, M.M.; Proctor, E.K.; EKirchner, J. A refined compilation of implementation strategies: Results from the Expert Recommendations for Implementing Change (ERIC) project. Implement. Sci. 2015, 10, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabak, R.G.; Khoong, E.C.; Chambers, D.A.; Brownson, R.C. Bridging research and practice: Models for dissemination and implementation research. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2012, 43, 337–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez, R.G.; Lewis, C.C.; Weiner, B.J. Instrumentation issues in implementation science. Implement. Sci. 2014, 9, 114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenhalgh, T.; Robert, G.; Macfarlane, F.; Bate, P.; Kyriakidou, O. Diffusion of innovations in service organizations: Systematic review and recommendations. Milbank Q. 2004, 82, 581–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mendel, P.; Meredith, L.S.; Schoenbaum, M.; Sherbourne, C.D.; Wells, K.B. Interventions in Organizational and Community Context: A Framework for Building Evidence on Dissemination and Implementation in Health Services Research. Adm. Policy Ment. Health Ment. Health Serv. Res. 2008, 35, 21–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mitchell, J.E.; Agras, S.; Crow, S.; Halmi, K.; Fairburn, C.G.; Bryson, S.; Kraemer, H. Stepped care and cognitive-behavioural therapy for bulimia nervosa: Randomised trial. Br. J. Psychiatry J. Ment. Sci. 2011, 198, 391–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gyani, A.; Shafran, R.; Rose, S.; Lee, M.J. A Qualitative Investigation of Therapists’ Attitudes towards Research: Horses for Courses? Behav. Cogn. Psychother. 2013, 43, 436–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tasca, G.A.; Sylvestre, J.; Balfour, L.; Chyurlia, L.; Evans, J.; Fortin-Langelier, B.; Francis, K.; Gandhi, J.; Huehn, L.; Hunsley, J.; et al. What clinicians want: Findings from a psychotherapy practice research network survey. Psychotherapy 2015, 52, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novins, D.K.; Green, A.E.; Legha, R.K.; Aarons, G.A. Dissemination and Implementation of Evidence-Based Practices for Child and Adolescent Mental Health: A Systematic Review. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2013, 52, 1009–1025.e18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Powell, B.J.; Proctor, E.K.; Glass, J.E. A Systematic Review of Strategies for Implementing Empirically Supported Mental Health Interventions. Res. Soc. Work. Pract. 2014, 24, 192–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ross, J.; Stevenson, F.; Lau, R.; Murray, E. Factors that influence the implementation of e-health: A systematic review of systematic reviews (an update). Implement. Sci. 2016, 11, 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drozd, F.; Vaskinn, L.; Bergsund, H.B.; Haga, S.M.; Slinning, K.; Bjorkli, C.A. The Implementation of Internet Interventions for Depression: A Scoping Review. J. Med. Internet Res. 2016, 18, e236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, L.A.; Augustsson, H.; Grødahl, A.I.; Pomare, C.; Churruca, K.; Long, J.C.; Ludlow, K.; Zurynski, Y.A.; Braithwaite, J. Implementation of e-mental health for depression and anxiety: A critical scoping review. J. Community Psychol. 2020, 48, 904–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, S.; Birken, S.A.; Melvin, C.L.; Rohweder, C.L.; Smith, J.D. Designs and methods for implementation research: Advancing the mission of the CTSA program. J. Clin. Trans. Sci. 2020, 4, 159–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G.; Altman, D.; Antes, G. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009, 6, e1000097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuijpers, P. Meta-Analyses in Mental Health Research: A Practical Guide; Vrije Universiteit: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Curran, G.M.; Bauer, M.; Mittman, B.; Pyne, J.M.; Stetler, C. Effectiveness-implementation hybrid designs: Combining elements of clinical effectiveness and implementation research to enhance public health impact. Med. Care 2012, 50, 217–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proctor, E.; Silmere, H.; Raghavan, R.; Hovmand, P.; Aarons, G.; Bunger, A.; Griffey, R.; Hensley, M. Outcomes for implementation research: Conceptual distinctions, measurement challenges, and research agenda. Adm. Policy Ment. Health Ment. Health Serv. Res. 2011, 38, 65–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, D.H.; Adam, T.; Alonge, O.; Agyepong, I.A.; Tran, N. Republished research: Implementation research: What it is and how to do it. Br. J. Sports Med. 2014, 48, 731–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Linde, K.; Rücker, G.; Sigterman, K.; Jamil, S.; Meissner, K.; Schneider, A.; Kriston, L. Comparative effectiveness of psychological treatments for depressive disorders in primary care: Network meta-analysis. BMC Fam. Pract. 2015, 16, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landsverk, J.; Brown, C.H.; Reutz, J.R.; Palinkas, L.; Horwitz, S.M. Design Elements in Implementation Research: A Structured Review of Child Welfare and Child Mental Health Studies. Adm. Policy Ment. Health 2011, 38, 54–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asrat, B.; Lund, C.; Ambaw, F.; Schneider, M. Acceptability and feasibility of peer-administered group interpersonal therapy for depression for people living with HIV/AIDS—A pilot study in Northwest Ethiopia. Pilot Feasibility Stud. 2021, 7, 147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bina, R.; Barak, A.; Posmontier, B.; Glasser, S.; Cinamon, T. Social workers’ perceptions of barriers to interpersonal therapy implementation for treating postpartum depression in a primary care setting in Israel. Health Soc. Care Community 2018, 26, E75–E84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bloomquist, M.L.; Giovanelli, A.; Benton, A.; Piehler, T.F.; Quevedo, K.; Oberstar, J. Implementation and Evaluation of Evidence-Based Psychotherapeutic Practices for Youth in a Mental Health Organization. J. Child Fam. Stud. 2016, 25, 3278–3292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.K.; Ingenito, C.P.; Kehn, M.M.; Nehrig, N.; Abraham, K.S. Implementing brief Dynamic Interpersonal Therapy (DIT) in a VA Medical Center. J. Ment. Health 2019, 28, 613–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clignet, F.; van Meijel, B.; van Straten, A.; Cuijpers, P. A Qualitative Evaluation of an Inpatient Nursing Intervention for Depressed Elderly: The Systematic Activation Method. Perspect. Psychiatr. Care 2017, 53, 280–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dear, B.F.; Johnson, B.; Singh, A.; Wilkes, B.; Brkic, T.; Gupta, R.; Jones, M.P.; Bailey, S.; Dudeney, J.; Gandy, M.; et al. Examining an internet-delivered intervention for anxiety and depression when delivered as a part of routine care for university students: A phase IV trial. J. Affect. Disord. 2019, 256, 567–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drozd, F.; Haga, S.M.; Lisøy, C.; Slinning, K. Evaluation of the implementation of an internet intervention in well-baby clinics: A pilot study. Internet Interv. 2018, 13, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eiraldi, R.; Khanna, M.S.; Jawad, A.F.; Fishman, J.; Glick, H.A.; Schwartz, B.S.; Cacia, J.; Wandersman, A.; Beidas, R. A hybrid effectiveness-implementation cluster randomized trial of group CBT for anxiety in urban schools: Rationale, design, and methods. Implement. Sci. 2016, 11, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fortney, J.; Enderle, M.; McDougall, S.; Clothier, J.; Otero, J.; Altman, L.; Curran, G. Implementation outcomes of evidence-based quality improvement for depression in VA community based outpatient clinics. Implement. Sci. 2012, 7, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuchs, C.H.; Haradhvala, N.; Evans, D.R.; Nash, J.M.; Weisberg, R.B.; Uebelacker, L.A. Implementation of an acceptance- and mindfulness-based group for depression and anxiety in primary care: Initial outcomes. Fam. Syst. Health 2016, 34, 386–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geraedts, A.S.; Kleiboer, A.M.; Wiezer, N.M.; Cuijpers, P.; Van Mechelen, W.; Anema, J.R. Feasibility of a worker-directed web-based intervention for employees with depressive symptoms. Internet Interv. 2014, 1, 132–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Hadjistavropoulos, H.D.; Nugent, M.M.; Dirkse, D.; Pugh, N. Implementation of internet-delivered cognitive behavior therapy within community mental health clinics: A process evaluation using the consolidated framework for implementation research. BMC Psychiatry 2017, 17, 331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Israel, P.; Diamond, G.S. Feasibility of Attachment Based Family Therapy for depressed clinic-referred Norwegian adolescents. Clin. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2013, 18, 334–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, J.E.; Hailemariam, M.; Zlotnickz, C.; Richie, F.; Sinclair, J.; Chuong, A.; Stirman, S.W. Mixed Methods Analysis of Implementation of Interpersonal Psychotherapy (IPT) for Major Depressive Disorder in Prisons in a Hybrid Type I Randomized Trial. Adm. Policy Ment. Health Ment. Health Serv. Res. 2020, 47, 410–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanine, R.M.; Bush, M.L.; Davis, M.; Jones, J.D.; Sbrilli, M.D.; Young, J.F. Depression Prevention in Pediatric Primary Care: Implementation and Outcomes of Interpersonal Psychotherapy—Adolescent Skills Training. Child Psychiatry Hum. Dev. 2021, 54, 96–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karlin, B.E.; Brown, G.K.; Jager-Hyman, S.; Green, K.L.; Wong, M.; Lee, D.S.; Bertagnolli, A.; Ross, T.B. Dissemination and Implementation of Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Depression in the Kaiser Permanente Health Care System: Evaluation of Initial Training and Clinical Outcomes. Behav. Ther. 2019, 50, 446–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kramer, T.L.; Burns, B.J. Implementing cognitive behavioral therapy in the real world: A case study of two mental health centers. Implement. Sci. 2008, 3, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindholm, L.H.; Koivukangas, A.; Lassila, A.; Kampman, O. What is important for the sustained implementation of evidence-based brief psychotherapy interventions in psychiatric care? A quantitative evaluation of a real-world programme. Nord. J. Psychiatry 2019, 73, 185–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lusk, P.; Melnyk, B.M. COPE for the treatment of depressed adolescents: Lessons learned from implementing an evidence-based practice change. J. Am. Psychiatr. Nurses Assoc. 2011, 17, 297–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacPherson, H.A.; Leffler, J.M.; Fristad, M.A. Implementation of Multi-Family Psychoeducational Psychotherapy for Childhood Mood Disorders in an Outpatient Community Setting. J. Marital. Fam. Ther. 2014, 40, 193–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mignogna, J.; Hundt, N.E.; Kauth, M.R.; Kunik, M.E.; Sorocco, K.H.; Naik, A.D.; A Stanlety, M.; York, K.M.; A Cully, J. Implementing brief cognitive behavioral therapy in primary care: A pilot study. Transl. Behav. Med. 2014, 4, 175–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mignogna, J.; Martin, L.A.; Harik, J.; Hundt, N.E.; Kauth, M.; Naik, A.D.; Sorocco, K.; Benzer, J.; Cully, J. “I had to somehow still be flexible”: Exploring adaptations during implementation of brief cognitive behavioral therapy in primary care. Implement. Sci. 2018, 13, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morrison, C.; Walker, G.; Ruggeri, K.; Hacker Hughes, J. An implementation pilot of the MindBalance web-based intervention for depression in three IAPT services. Cogn. Behav. Ther. 2014, 7, e15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parhiala, P.; Ranta, K.; Gergov, V.; Kontunen, J.; Law, R.; La Greca, A.M.; Torppa, M.; Marttunen, M. Interpersonal Counseling in the Treatment of Adolescent Depression: A Randomized Controlled Effectiveness and Feasibility Study in School Health and Welfare Services. Sch. Ment. Health 2020, 12, 265–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterson, R.; Darnell, D.; Berliner, L.; Dorsey, S.; Murray, L.; Monroe-DeVita, M. Implementing Transdiagnostic Cognitive Behavioral Psychotherapy in Adult Public Behavioral Health: A Pilot Evaluation of the Feasibility of the Common Elements Treatment Approach (CETA). J. Behav. Health Serv. Res. 2019, 46, 249–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rasmussen, L.M.P.; Patras, J.; Neumer, S.P.; Adolfsen, F.; Martinsen, K.D.; Holen, S.; Sund, A.M.; Martinussen, M. Facilitators and Barriers to the Implementation of EMOTION: An Indicated Intervention for Young Schoolchildren. Scand. J. Educ. Res. 2020, 64, 728–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santucci, L.C.; Thomassin, K.; Petrovic, L.; Weisz, J.R. Building Evidence-Based Interventions for the Youth, Providers, and Contexts of Real-World Mental-Health Care. Child Dev. Perspect. 2015, 9, 67–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sit, H.F.; Hong, I.W.; Burchert, S.; Sou, E.K.L.; Wong, M.; Chen, W.; Lam, A.I.F.; Hall, B.J. A Feasibility Study of the WHO Digital Mental Health Intervention Step-by-Step to Address Depression Among Chinese Young Adults. Front. Psychiatry 2022, 12, 812667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinfeld, B.I.; Coffman, S.J.; Keyes, J.A. Implementation of an evidence-based practice in a clinical setting: What happens when you get there? Prof. Psychol. Res. Pract. 2009, 40, 410–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walser, R.D.; Karlin, B.E.; Trockel, M.; Mazina, B.; Barr Taylor, C. Training in and implementation of Acceptance and Commitment Therapy for depression in the Veterans Health Administration: Therapist and patient outcomes. Behav. Res. Ther. 2013, 51, 555–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilfley, D.E.; Agras, W.S.; Fitzsimmons-Craft, E.E.; Bohon, C.; Eichen, D.M.; Welch, R.R.; Robinson, A.H.; Jo, B.; Raghavan, R.; Proctor, E.K.; et al. Training Models for Implementing Evidence-Based Psychological Treatment: A Cluster-Randomized Trial in College Counseling Centers. JAMA Psychiatry 2020, 77, 139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varkey, P.; Reller, M.K.; Resar, R.K. Basics of Quality Improvement in Health Care. Mayo Clin. Proc. 2007, 82, 735–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- May, C.R.; Mair, F.; Finch, T.; MacFarlane, A.; Dowrick, C.; Treweek, S.; Rapley, T.; Ballini, L.; Ong, B.N.; Rogers, A.; et al. Development of a theory of implementation and integration: Normalization Process Theory. Implement. Sci. 2009, 4, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aarons, G.A.; Hurlburt, M.; Horwitz, S.M.C. Advancing a conceptual model of evidence-based practice implementation in public service sectors. Adm. Policy Ment. Health Ment. Health Serv. Res. 2011, 38, 4–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stetler, C.B.; Damschroder, L.J.; Helfrich, C.D.; Hagedorn, H.J. A Guide for applying a revised version of the PARIHS framework for implementation. Implement. Sci. 2011, 6, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuijpers, P.; Miguel, C.; Harrer, M.; Plessen, C.Y.; Ciharova, M.; Papola, D.; Ebert, D.; Karyotaki, E. Psychological treatment of depression: A systematic overview of a ‘Meta-Analytic Research Domain’. J. Affect. Disord. 2023, 335, 141–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cochrane, L.J.; Olson, C.A.; Murray, S.; Dupuis, M.; Tooman, T. Gaps Between Knowing and Doing Understanding and Assessing the Barriers to Optimal Health Care. J. Contin. Educ. Health Prof. 2008, 28, 157–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Birken, S.A.; Powell, B.J.; Shea, C.M.; Haines, E.R.; Alexis Kirk, M.; Leeman, J.; Rohweder, C.; Damschroder, L.; Presseau, J. Criteria for selecting implementation science theories and frameworks: Results from an international survey. Implement. Sci. 2017, 12, 124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, B.B.; Coronado, G.D.; Schwartz, M.; Coury, J.; Baldwin, L.M. Using a continuum of hybrid effectiveness- implementation studies to put research- tested colorectal screening interventions into practice. Implement. Sci. 2019, 14, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boydell, K.M.; Stasiulis, E.; Barwick, M.; Greenberg, N.; Pong, R. Challenges of knowledge translation in rural communities: The case of rural children’s mental health. Can. J. Community Ment. Health 2008, 27, 49–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bond, G.R.; Drake, R.E.; McHugo, G.J.; Peterson, A.E.; Jones, A.M.; Williams, J. Long-term sustainability of evidence-based practices in community mental health agencies. Adm. Policy Ment. Health 2014, 41, 228–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, C.C.; Fischer, S.; Weiner, B.J.; Stanick, C.; Kim, M.; Martinez, R.G. Outcomes for implementation science: An enhanced systematic review of instruments using evidence-based rating criteria. Implement. Sci. 2015, 10, 155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huynh, A.K.; Hamilton, A.B.; Farmer, M.M.; Bean-Mayberry, B.; Stirman, S.W.; Moin, T.; Finley, E.P. A Pragmatic Approach to Guide Implementation Evaluation Research: Strategy Mapping for Complex Interventions. Front. Public Health 2018, 6, 134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wells, K.B. Treatment research at the crossroads: The scientific interface of clinical trials and effectiveness research. Am. J. Psychiatry 1999, 156, 5–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, A.L.; Ecker, A.H.; Fletcher, T.L.; Hundt, N.; Kauth, M.R.; Martin, L.A.; Curran, G.M.; A Cully, J. Increasing the impact of randomized controlled trials: An example of a hybrid effectivenessa-implementation design in psychotherapy research. Transl. Behav. Med. 2020, 10, 629–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagermoser Sanetti, L.M.; Collier-Meek, M.A. Increasing implementation science literacy to address the research-to-practice gap in school psychology. J. Sch. Psychol. 2019, 76, 33–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Study | Goal of the Study | Units of Analysis |

|---|---|---|

| Asrat et al., 2021 [46] | To assess the acceptability and feasibility of peer-administered group IPT for depressive symptoms among people living with HIV/AIDS in Northwest Ethiopia. | Peer-counsellors, supervisors, and patients |

| Bina et al., 2017 [47] | To examine social workers’ perspectives of provider- and organization-related barriers to implementing IPTin a primary care setting in Israel for women who have postpartum depression symptoms. | Social workers |

| Bloomquist et al., 2017 [48] | To describe the Health Emotions Programs and Behaviour Development Program to address depression and behavior problems of adolescents demonstrating how they were brought into a community mental health setting and evaluated for their effects on youth and family outcomes. | Patients, practitioners, parents |

| Chen et al., 2019 [49] | Describe and assess feasibility and implementation process of Dynamic Interpersonal Therapy to address Veterans Affairs depression in medical center considering providers, patients, and systems barriers. | Patients, Therapists |

| Clignet et al., 2016 [50] | To explore the nurses’ perceptions of the barriers and facilitators in the implementation of an intervention Systematic Activation Method to address late-life depression in mental health nursing care. | Nurses, patients |

| Dear et al., 2020 [51] | Assess the acceptability and effectiveness of an internet-delivered and therapist-guided intervention, UniWellbeing, to address anxiety and depression, when delivered as routine care for students attending a university counselling service. | Patients |

| Drozd et al., 2018 [52] | To assess training and implementation of an internet intervention (MammaMia) to address perinatal depression in Norwegian well-baby clinics examining implementation variables, barriers, and facilitators. | Health and administrative staff and organization |

| Eiraldi et al., 2019 [53] | To describe the fidelity, perceived acceptability, and student outcomes of a group CBT in schools | Students, parents and school staff |

| Fortney et al., 2012 [54] | To evaluate the feasibility of evidence-based quality improvement as a strategy to facilitate the adoption of Collaborative-care management in Community-Based outpatient Clinics to address Veterans’ Affairs depression. | Organization, staff, patients |

| Fuchs et al., 2016 [55] | To evaluate the implementation of an acceptance and mindfulness-based group for primary care patients with depression and anxiety considering the group’s feasibility, acceptability, penetration, and sustainability, and provide initial outcome data. | Patients |

| Geraedts et al., 2014 [56] | To assess the feasibility of the intervention Happy@Work and explore possible barriers and facilitators for future implementation of the intervention into routine practice. | Patients and intervention providers and organization |

| Hadjistavropoulos et al., 2017 [57] | To assess and identify barriers and facilitators that influenced Internet-delivered CBT implementation in community mental health clinics distributed across one province. | Therapist and managers |

| Israel et al., 2013 [58] | To assess the feasibility of the intervention Attachment-Based Family Therapy to address depression in a hospital-based public mental health clinic, select regular staff therapists for training and test the intervention effectiveness. | Patients and therapists and institution |

| Johnson et al., 2020 [59] | To assess potentially influencing factors in the implementation of IPT for depression in prisons considering feasibility and acceptability. | Patients, providers, and administrators |

| Kanine et al., 2021 [60] | To assess fidelity, feasibility, and acceptability of delivering IPT-AST to adolescents from marginalized backgrounds within urban PC. | Patients, caregivers, and supervisor. |

| Karlin et al., 2019 [61] | To train professionals in CBT-D and examine initial feasibility and effectiveness of individualized training in and implementation of the intervention. | Patients and therapists. |

| Kramer et al., 2008 [62] | To assess the implementation of CBT for depressed adolescents seeking public sector mental health services, focusing on the extent it was implemented in two publicly funded mental healthcare clinics and the process and the factors influencing it. | Patients, therapists, and organization |

| Lindholm et al., 2019 [63] | Assess the quantitative reach of the EBT and the explanatory factors considering the therapists’ views on the usefulness of BA on addressing depression. | Therapists |

| Lusk et al., 2011 [64] | To promote the implementation of the COPE program to adolescents experiencing depressive symptoms and to determine feasibility and efficacy with this population. | Patients, psychiatric nurses, and parents |

| MacPherson et al., 2014 [65] | To assess descriptive and quantitative data on the implementation of MF-PEP at two outpatient community clinics for children with mood disorders and their parents using Proctor implementation outcome taxonomy. | Parents, children, MF-PEP therapists, referring clinicians and agency-level observations. |

| Mignogna et al., 2014 [66] | To assess feasibility and acceptability of a multifaceted implementation strategies in the implementation of a bCBT to address depression and/or anxiety in PC considering preliminary fidelity and adoption measures. | Clinicians |

| Mignogna et al., 2018 [67] | To assess provider’s perspectives on fidelity of bCBT implemented in PC settings. | Providers |

| Morrison et al., 2014 [68] | To explore the Type 2 translation gap by conducting an implementation pilot of MindBalance, a web-based intervention for depression in three IAPT services. | Patients |

| Parhiala et al., 2019 [69] | To assess the effectiveness, feasibility, and acceptability of IPC as compared with BPS in Finnish schools. | Patients and counsellors |

| Peterson et al., 2018 [70] | To evaluate the implementation strategies used and feasibility of implementing CETA in Washington State PBH. | Clinicians and patients |

| Rasmussen et al., 2019 [71] | To identify barriers and facilitators in the active phase of the EPIS model in the implementation of the EMOTION program within the group leaders’ organizational context. | Group leaders and organization |

| Santucci et al., 2014 [72] | To assess feasibility, acceptability and effectiveness of the implementation of the program BtB to address depression and anxiety in a university-based health setting. | Patients |

| Sit et al., 2022 [73] | To assess the feasibility and preliminary effectiveness of delivering Step-by-Step in a University setting for Chinese young adults with minimal peer-support guidance model to address depression and anxiety. | Patients |

| Steinfeld et al., 2009 [74] | To describe the experience of psychologists who designed and implemented an intensive training program to diffuse one CBT for the treatment of anxiety and depression in a large mental health services delivery system. | Mental health providers and organization |

| Walser et al., 2013 [75] | To assess the training of mental health clinicians in ACT-D considering the impact of the implementation in professionals and the patients. | Therapist and patients |

| Wilfley et al., 2020 [76] | To compare two methods of training in IPT to address university students with depression and/or eating disorders. | Therapists |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lorente-Català, R.; Díaz-García, A.; Jaén, I.; Gili, M.; Mayoral, F.; García-Campayo, J.; López-Del-Hoyo, Y.; Castro, A.; Hurtado, M.M.; Planting, C.H.M.; et al. Implementation of Evidence-Based Psychological Treatments to Address Depressive Disorders: A Systematic Review. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 6347. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14176347

Lorente-Català R, Díaz-García A, Jaén I, Gili M, Mayoral F, García-Campayo J, López-Del-Hoyo Y, Castro A, Hurtado MM, Planting CHM, et al. Implementation of Evidence-Based Psychological Treatments to Address Depressive Disorders: A Systematic Review. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(17):6347. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14176347

Chicago/Turabian StyleLorente-Català, Rosa, Amanda Díaz-García, Irene Jaén, Margalida Gili, Fermín Mayoral, Javier García-Campayo, Yolanda López-Del-Hoyo, Adoración Castro, María M. Hurtado, Caroline H. M. Planting, and et al. 2025. "Implementation of Evidence-Based Psychological Treatments to Address Depressive Disorders: A Systematic Review" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 17: 6347. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14176347

APA StyleLorente-Català, R., Díaz-García, A., Jaén, I., Gili, M., Mayoral, F., García-Campayo, J., López-Del-Hoyo, Y., Castro, A., Hurtado, M. M., Planting, C. H. M., & García-Palacios, A. (2025). Implementation of Evidence-Based Psychological Treatments to Address Depressive Disorders: A Systematic Review. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(17), 6347. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14176347