Interest in Fertility Preservation Among Adults Seen at a Gender Care Clinic

Abstract

1. Background

2. Materials and Methods

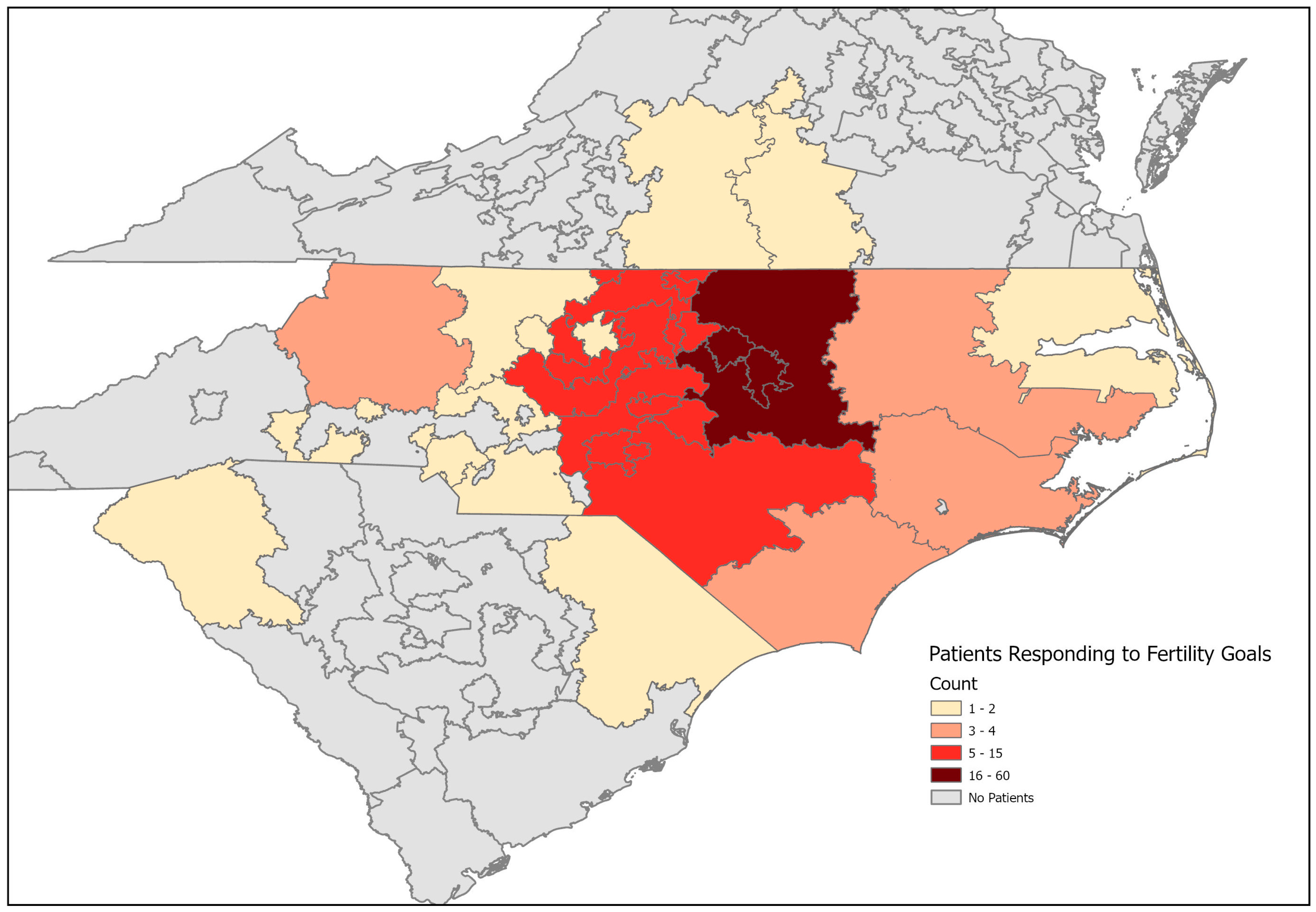

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Study Sample

2.3. Data Sources

2.4. Measures/Variables

2.5. Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Sample Demographics

3.2. Psychological and Social Support Measures

3.3. Participant Characteristics and Fertility Preferences

3.4. Reasons for Electing Not to Pursue FP

3.5. Predictors of IFP

3.6. Referrals to Fertility Preservation and Fertility Preservation Rates

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- LGBT FAQs. Available online: https://williamsinstitute.law.ucla.edu/quick-facts/lgbt-faqs/ (accessed on 26 May 2025).

- Judge, C.; O’Donovan, C.; Callaghan, G.; Gaoatswe, G.; O’Shea, D. Gender Dysphoria—Prevalence and Co-Morbidities in an Irish Adult Population. Front. Endocrinol. 2014, 5, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nahata, L.; Tishelman, A.C.; Caltabellotta, N.M.; Quinn, G.P. Low Fertility Preservation Utilization Among Transgender Youth. J. Adolesc. Health 2017, 61, 40–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alpern, S.; Yaish, I.; Wagner-Kolasko, G.; Greenman, Y.; Sofer, Y.; Paltiel Lifshitz, D.; Groutz, A.; Azem, F.; Amir, H. Why Fertility Preservation Rates of Transgender Men Are Much Lower than Those of Transgender Women. Reprod. Biomed. Online 2022, 44, 943–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.; Simons, L.; Johnson, E.K.; Lockart, B.A.; Finlayson, C. Fertility Preservation for Transgender Adolescents. J. Adolesc. Health 2017, 61, 120–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ethics Committee of the American Society for Reproductive Medicine. Access to Fertility Services by Transgender and Nonbinary Persons: An Ethics Committee Opinion. Fertil. Steril. 2021, 115, 874–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coleman, E.; Radix, A.E.; Bouman, W.P.; Brown, G.R.; De Vries, A.L.C.; Deutsch, M.B.; Ettner, R.; Fraser, L.; Goodman, M.; Green, J.; et al. Standards of Care for the Health of Transgender and Gender Diverse People, Version 8. Int. J. Transgend. Health 2022, 23, S1–S259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hembree, W.C.; Cohen-Kettenis, P.T.; Gooren, L.; Hannema, S.E.; Meyer, W.J.; Murad, M.H.; Rosenthal, S.M.; Safer, J.D.; Tangpricha, V.; T’Sjoen, G.G. Endocrine Treatment of Gender-Dysphoric/Gender-Incongruent Persons: An Endocrine Society Clinical Practice Guideline. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2017, 102, 3869–3903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Defreyne, J.; Van Schuylenbergh, J.; Motmans, J.; Tilleman, K.L.; T’Sjoen, G.G.R. Parental Desire and Fertility Preservation in Assigned Female at Birth Transgender People Living in Belgium. Fertil. Steril. 2020, 113, 149–157.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cocchetti, C.; Romani, A.; Collet, S.; Greenman, Y.; Schreiner, T.; Wiepjes, C.; den Heijer, M.; T’Sjoen, G.; Fisher, A.D. The ENIGI (European Network for the Investigation of Gender Incongruence) Study: Overview of Acquired Endocrine Knowledge and Future Perspectives. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 1784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riggs, D.W.; Bartholomaeus, C. Fertility Preservation Decision Making amongst Australian Transgender and Non-Binary Adults. Reprod. Health 2018, 15, 181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auer, M.K.; Fuss, J.; Nieder, T.O.; Briken, P.; Biedermann, S.V.; Stalla, G.K.; Beckmann, M.W.; Hildebrandt, T. Desire to Have Children Among Transgender People in Germany: A Cross-Sectional Multi-Center Study. J. Sex. Med. 2018, 15, 757–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garborcauskas, G.; McCabe, E.; Boskey, E.R.; Grimstad, F.W. Family Building Perspectives of Assigned Female at Birth Transgender and Gender Diverse Adolescents Seeking Testosterone Gender-Affirming Hormone Therapy. LGBT Health 2022, 9, 463–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, H.C.; Long, J.; Aye, T. Fertility Preservation in Transgender and Non-Binary Adolescents and Young Adults. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0265043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baram, S.; Myers, S.A.; Yee, S.; Librach, C.L. Fertility Preservation for Transgender Adolescents and Young Adults: A Systematic Review. Hum. Reprod. Update 2019, 25, 694–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wierckx, K.; Van Caenegem, E.; Pennings, G.; Elaut, E.; Dedecker, D.; Van de Peer, F.; Weyers, S.; De Sutter, P.; T’Sjoen, G. Reproductive Wish in Transsexual Men. Hum. Reprod. 2012, 27, 483–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vyas, N.; Douglas, C.R.; Mann, C.; Weimer, A.K.; Quinn, M.M. Access, Barriers, and Decisional Regret in Pursuit of Fertility Preservation among Transgender and Gender-Diverse Individuals. Fertil. Steril. 2021, 115, 1029–1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadgauda, A.S.; Butts, S. Barriers to Fertility Preservation Access in Transgender and Gender Diverse Adolescents: A Narrative Review. Ther. Adv. Reprod. Health 2024, 18, 26334941231222120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morong, J.J.; Class, Q.A.; Zamah, A.M.; Hinz, E. Parenting Intentions in Transgender and Gender-nonconforming Adults. Int. J. Gynecol. Obstet. 2022, 159, 557–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stolk, T.H.R.; Asseler, J.D.; Huirne, J.A.F.; van den Boogaard, E.; van Mello, N.M. Desire for Children and Fertility Preservation in Transgender and Gender-Diverse People: A Systematic Review. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2023, 87, 102312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parvez, M.A.; Leemaqz, S.Y.; Irwig, M.S. The Desire for Parenthood and Biological Children among Adult Transgender and Gender-Diverse Individuals Seeking Gender-Affirming Care. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2025, 232, e165–e169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PROMIS. Available online: https://www.healthmeasures.net/score-and-interpret/interpret-scores/promis (accessed on 25 May 2025).

- Widmer, R.; Knabben, L.; Bitterlich, N.; von Wolff, M.; Stute, P. Motives for Desiring Children among Individuals of Different Sexual–Romantic Orientations: A Cross-Sectional Study. Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 2024, 309, 707–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minkin, R.; Horowitz, J.M.; Aragão, C. The Experiences of U.S. Adults Who Don’t Have Children; Pew Research Center: Washington, DC, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Neal, J.W.; Neal, Z.P. Tracking Types of Non-parents in the United States. J. Marriage Fam. 2025, 87, 1747–1762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurst, K. What Do Americans Think About Fewer People Choosing to Have Children? Pew Research Center: Washington, DC, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Selter, J.; Huang, Y.; Grossman Becht, L.C.; Palmerola, K.L.; Williams, S.Z.; Forman, E.; Ananth, C.V.; Hur, C.; Neugut, A.I.; Hershman, D.L.; et al. Use of Fertility Preservation Services in Female Reproductive-Aged Cancer Patients. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2019, 221, 328.e1–328.e16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meernik, C.; Engel, S.M.; Wardell, A.; Baggett, C.D.; Gupta, P.; Rodriguez-Ormaza, N.; Luke, B.; Baker, V.L.; Wantman, E.; Rauh-Hain, J.A.; et al. Disparities in Fertility Preservation Use among Adolescent and Young Adult Women with Cancer. J. Cancer Surviv. Res. Pract. 2023, 17, 1435–1444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Lan, Q.-Y.; Zhu, W.-B.; Fan, L.-Q.; Huang, C. Fertility Preservation in Adult Male Patients with Cancer: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Hum. Reprod. Open 2024, 2024, hoae006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The Status of Fertility Preservation (FP) Insurance Mandates and Their Impact on Utilization and Access to Care. Available online: https://www.mdpi.com/2077-0383/13/4/1072 (accessed on 3 August 2025).

- Gale, J.; Magee, B.; Forsyth-Greig, A.; Visram, H.; Jackson, A. Oocyte Cryopreservation in a Transgender Man on Long-Term Testosterone Therapy: A Case Report. FS Rep. 2021, 2, 249–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sample | Interested in Fertility Preservation | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total (n = 206) | Yes/Unsure (n = 54) | No (n = 152) | ||||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | p-Value 11 | ||

| Age | 18–21 | 50 | 24.3 | 13 | 24.1 | 37 | 24.3 | 0.1 |

| 22–26 | 53 | 25.7 | 19 | 35.2 | 34 | 22.4 | ||

| 27–34 | 51 | 24.8 | 14 | 25.9 | 37 | 24.3 | ||

| ≥35 | 52 | 25.2 | 8 | 14.8 | 44 | 29.0 | ||

| Designated Sex at Birth | Female | 113 | 54.9 | 29 | 53.7 | 84 | 55.3 | 0.8 |

| Male | 93 | 45.2 | 25 | 46.3 | 68 | 44.7 | ||

| Gender Identity 1 | Transgender Male+ 2 | 80 | 38.8 | 22 | 40.7 | 58 | 38.2 | 0.9 |

| Transgender Female+ 3 | 84 | 40.8 | 21 | 38.9 | 63 | 41.5 | ||

| Non-binary/Genderqueer 4 | 42 | 20.4 | 11 | 20.4 | 31 | 20.4 | ||

| Sexual Orientation 5 | Asexual | 8 | 4.4 | 1 | 2.1 | 7 | 5.1 | 0.06 |

| Bisexual | 15 | 8.2 | 1 | 2.1 | 14 | 10.2 | ||

| Gay | 7 | 3.8 | 2 | 4.3 | 5 | 3.7 | ||

| Lesbian | 11 | 6.0 | 6 | 12.8 | 5 | 3.7 | ||

| Do not label sexuality | 23 | 12.5 | 10 | 21.3 | 13 | 9.5 | ||

| Pansexual | 25 | 13.6 | 7 | 14.9 | 18 | 13.1 | ||

| Queer | 25 | 13.6 | 6 | 12.8 | 19 | 13.9 | ||

| Straight/Heterosexual | 18 | 9.8 | 2 | 4.3 | 16 | 11.7 | ||

| Not listed | 7 | 3.8 | 3 | 6.4 | 4 | 2.9 | ||

| More than one selected | 45 | 24.5 | 9 | 19.2 | 36 | 26.3 | ||

| Choose not to disclose/Missing 6 | 22 | - | 5 | - | 17 | - | ||

| Race and Ethnicity | Hispanic Latino | 14 | 7.2 | 4 | 8.3 | 10 | 6.9 | 0.08 |

| Non-Hispanic Asian | 4 | 2.1 | 1 | 2.1 | 3 | 2.1 | ||

| Non-Hispanic Black | 21 | 10.8 | 10 | 20.8 | 11 | 7.5 | ||

| Non-Hispanic Other 7 | 6 | 3.1 | 2 | 4.2 | 4 | 2.7 | ||

| Non-Hispanic White | 149 | 76.8 | 31 | 64.6 | 118 | 80.8 | ||

| Missing | 12 | - | 6 | - | 6 | - | ||

| Education | ≤High School or GED | 38 | 21.2 | 7 | 15.2 | 31 | 23.3 | 0.06 |

| Some College or Associates | 74 | 41.3 | 27 | 58.7 | 47 | 35.3 | ||

| Bachelors | 43 | 24.0 | 8 | 17.4 | 35 | 26.3 | ||

| Master’s or PhD | 24 | 13.4 | 4 | 8.7 | 20 | 15.0 | ||

| Missing | 27 | - | 8 | - | 19 | - | ||

| Employment | Full-Time | 68 | 37.2 | 9 | 20.0 | 59 | 42.8 | 0.02 |

| Part-Time 8 | 30 | 16.4 | 9 | 20.0 | 21 | 15.2 | ||

| Student 9 | 46 | 25.1 | 14 | 31.1 | 32 | 23.2 | ||

| Retired | 6 | 3.3 | 0 | 0.0 | 6 | 4.4 | ||

| Disability or Unemployed | 33 | 18.0 | 13 | 28.9 | 20 | 14.5 | ||

| Missing | 23 | - | 9 | - | 14 | - | ||

| HRT | Yes | 72 | 35.1 | 16 | 29.6 | 56 | 37.1 | 0.3 |

| No | 133 | 64.9 | 38 | 70.4 | 95 | 62.9 | ||

| Missing | 1 | - | 0 | - | 1 | - | ||

| Suicide Plan or Attempt | Yes | 72 | 36.4 | 22 | 41.5 | 50 | 34.5 | 0.4 |

| No | 126 | 63.6 | 31 | 58.5 | 95 | 65.5 | ||

| Missing | 8 | - | 1 | - | 7 | - | ||

| PROMIS category | <50 | 51 | 32.9 | 19 | 44.2 | 32 | 28.6 | 0.1 |

| ≥50 | 104 | 67.1 | 24 | 55.8 | 80 | 71.4 | ||

| Missing | 51 | - | 11 | - | 40 | - | ||

| Parents Support Identity | Yes | 94 | 45.9 | 22 | 40.7 | 72 | 47.7 | 0.4 |

| No | 111 | 54.2 | 32 | 59.3 | 79 | 52.3 | ||

| Missing | 1 | - | 0 | - | 1 | - | ||

| Marital Status | Married | 43 | 21.3 | 4 | 7.6 | 39 | 26.2 | 0.003 |

| Not Married | 159 | 78.7 | 49 | 92.5 | 110 | 73.8 | ||

| Missing | 4 | - | 1 | - | 3 | - | ||

| Already has children 10 | Yes | 38 | 18.5 | 4 | 7.4 | 34 | 22.4 | 0.01 |

| No | 168 | 81.6 | 50 | 92.6 | 118 | 77.6 | ||

| Reason | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| Too Expensive | 37 | 19.9 |

| Do not want bio kids | 104 | 55.9 |

| Prefer to adopt | 38 | 20.4 |

| Hope to still have despite HRT | 9 | 4.8 |

| Distress/Worsen Dysphoria | 36 | 19.4 |

| Not listed (write in) | 35 | 18.8 |

| Write in: Have kids already | 17 | 9.1 |

| Write in: Older age-related | 5 | 2.7 |

| Write in: Partner/Preserved * | 4 | 2.2 |

| OR 2 | 95% CI | p-Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | Per 5-year increase | 0.83 | (0.70, 0.98) | 0.03 |

| Designated Sex at Birth | Female | 1 | ||

| Male | 1.07 | (0.57, 1.99) | 0.8 | |

| Gender Identity | Non-binary/Genderqueer | 1 | ||

| Transgender Female+ | 0.94 | (0.40, 2.19) | 0.9 | |

| Transgender Male+ | 1.07 | (0.46, 2.49) | ||

| Race and Ethnicity | Non-Hispanic White | 1 | ||

| Non-Hispanic Asian | 1.27 | (0.02, 16.41) | 1.0 | |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 3.43 | (1.19, 9.84) | 0.02 | |

| Non-Hispanic Other | 1.89 | (0.16, 13.93) | 0.8 | |

| Hispanic Latino | 1.52 | (0.33, 5.73) | 0.7 | |

| Education | ≤High School or GED | 1 | ||

| Some College or Associates | 2.52 | (0.92, 7.73) | 0.08 | |

| Bachelors | 1.01 | (0.28, 3.70) | 1.0 | |

| Master’s or PhD | 0.89 | (0.17, 4.05) | 1.0 | |

| Employment | Full-Time | 1 | ||

| Part-Time | 2.78 | (0.85, 9.13) | 0.1 | |

| Student | 2.84 | (1.02, 8.34) | 0.05 | |

| Retired | 0.85 | (0.00, 4.92) | 0.9 | |

| Disability or Unemployed | 4.19 | (1.42, 13.00) | 0.01 | |

| HRT | No | 1 | ||

| Yes | 0.71 | (0.37, 1.40) | 0.3 | |

| Suicide Plan or Attempt | No | 1 | ||

| Yes | 1.35 | (0.71, 2.57) | 0.4 | |

| PROMIS category | <50 | 1 | ||

| ≥50 | 0.51 | (0.24, 1.05) | 0.07 | |

| Parents Support Identity | No | 1 | ||

| Yes | 0.75 | (0.40, 1.42) | 0.4 | |

| Marital Status | Not Married | 1 | ||

| Married | 0.23 | (0.06, 0.69) | 0.005 | |

| Already has children | No | 1 | ||

| Yes | 0.28 | (0.07, 0.84) | 0.02 |

| OR 2 | 95% CI | p-Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MODEL 1 | ||||

| Age | Per 5-year increase | 0.91 | (0.76, 1.08) | 0.3 |

| Marital status | No | 1 | ||

| Yes | 0.29 | (0.07, 0.98) | 0.05 * | |

| MODEL 2 | ||||

| Age | Per 5-year increase | 0.90 | (0.74, 1.11) | 0.3 |

| Already has children | No | 1 | ||

| Yes | 0.41 | (0.08, 1.58) | 0.3 | |

| MODEL 3 | ||||

| Marital status | No | 1 | ||

| Yes | 0.29 | (0.07, 0.90) | 0.03 * | |

| Already has children | No | 1 | ||

| Yes | 0.38 | (0.09, 1.19) | 0.1 | |

| Model 4 | ||||

| Age | Per 5-year increase | 0.99 | (0.80, 1.22) | 0.9 |

| Marital status | No | 1 | ||

| Yes | 0.30 | (0.07, 0.99) | 0.05 * | |

| Already has children | No | 1 | ||

| Yes | 0.40 | (0.07, 1.61) | 0.26 | |

| MODEL 5 | ||||

| Age | Per 5-year increase | 0.91 | (0.72, 1.17) | 0.5 |

| Marital status | No | 1 | ||

| Yes | 0.44 | (0.10, 1.60) | 0.3 | |

| Already has children | No | 1 | ||

| Yes | 0.55 | (0.11, 2.34) | 0.6 | |

| Race and ethnicity | Non-Hispanic White | 1 | ||

| Non-Hispanic Asian | 0.91 | (0.02, 11.93) | 1.0 | |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 3.06 | (1.04, 9.02) | 0.04 * | |

| Non-Hispanic Other | 1.39 | (0.12, 10.32) | 1.0 | |

| Hispanic Latino | 1.51 | (0.32, 5.95) | 0.7 | |

| MODEL 6 | ||||

| Age | Per 5-year increase | 1.03 | (0.75, 1.42) | 0.9 |

| Marital status | No | 1 | ||

| Yes | 0.43 | (0.09, 1.66) | 0.3 | |

| Already has children | No | 1 | ||

| Yes | 0.48 | (0.07, 2.24) | 0.5 | |

| Employment 3 | Full-Time | 1 | ||

| Part-Time | 2.81 | (0.81, 9.80) | 0.1 | |

| Student | 2.47 | (0.78, 8.28) | 0.1 | |

| Disability or Unemployed | 4.10 | (1.37, 12.88) | 0.01 * | |

| MODEL 7 | ||||

| Age | Per 5-year increase | 0.97 | (0.74, 1.28) | 0.8 |

| Marital status | No | 1 | ||

| Yes | 0.31 | (0.05, 1.21) | 0.1 | |

| Already has children | No | 1 | ||

| Yes | 0.61 | (0.11, 2.57) | 0.7 | |

| Education | ≤High School or GED | 1 | ||

| Some College or Associates | 2.51 | (0.90, 7.80) | 0.08 | |

| Bachelors | 1.10 | (0.27, 4.45) | 1.0 | |

| Master’s or PhD | 1.22 | (0.20, 6.69) | 1.0 | |

| MODEL 8 | ||||

| Age | Per 5-year increase | 0.87 | (0.67, 1.13) | 0.3 |

| Marital status | No | 1 | ||

| Yes | 0.47 | (0.10, 1.70) | 0.3 | |

| Already has children | No | 1 | ||

| Yes | 0.54 | (0.08, 2.47) | 0.6 | |

| PROMIS50 | <50 | 1 | ||

| ≥50 | 0.52 | (0.24, 1.11) | 0.1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jones, Q.; Carlson, S.M.; Agrawala, S.; Weinhold, A.; Parnell, H.E.; Holliday, K.M.; Kelley, C.E. Interest in Fertility Preservation Among Adults Seen at a Gender Care Clinic. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 6175. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14176175

Jones Q, Carlson SM, Agrawala S, Weinhold A, Parnell HE, Holliday KM, Kelley CE. Interest in Fertility Preservation Among Adults Seen at a Gender Care Clinic. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(17):6175. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14176175

Chicago/Turabian StyleJones, Quinnette, Scott M. Carlson, Shilpi Agrawala, Andrew Weinhold, Heather E. Parnell, Katelyn M. Holliday, and Carly E. Kelley. 2025. "Interest in Fertility Preservation Among Adults Seen at a Gender Care Clinic" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 17: 6175. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14176175

APA StyleJones, Q., Carlson, S. M., Agrawala, S., Weinhold, A., Parnell, H. E., Holliday, K. M., & Kelley, C. E. (2025). Interest in Fertility Preservation Among Adults Seen at a Gender Care Clinic. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(17), 6175. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14176175