Implementation of a Hybrid Cardiac Rehabilitation and Symptom Scoring System in Patients with Inappropriate or Postural Sinus Tachycardia Referred for Sinus Node Sparing Hybrid Ablation

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Patient Population

2.2. Study Protocol

2.3. SNS Procedure

2.4. Program Protocol of Inpatient Rehabilitation

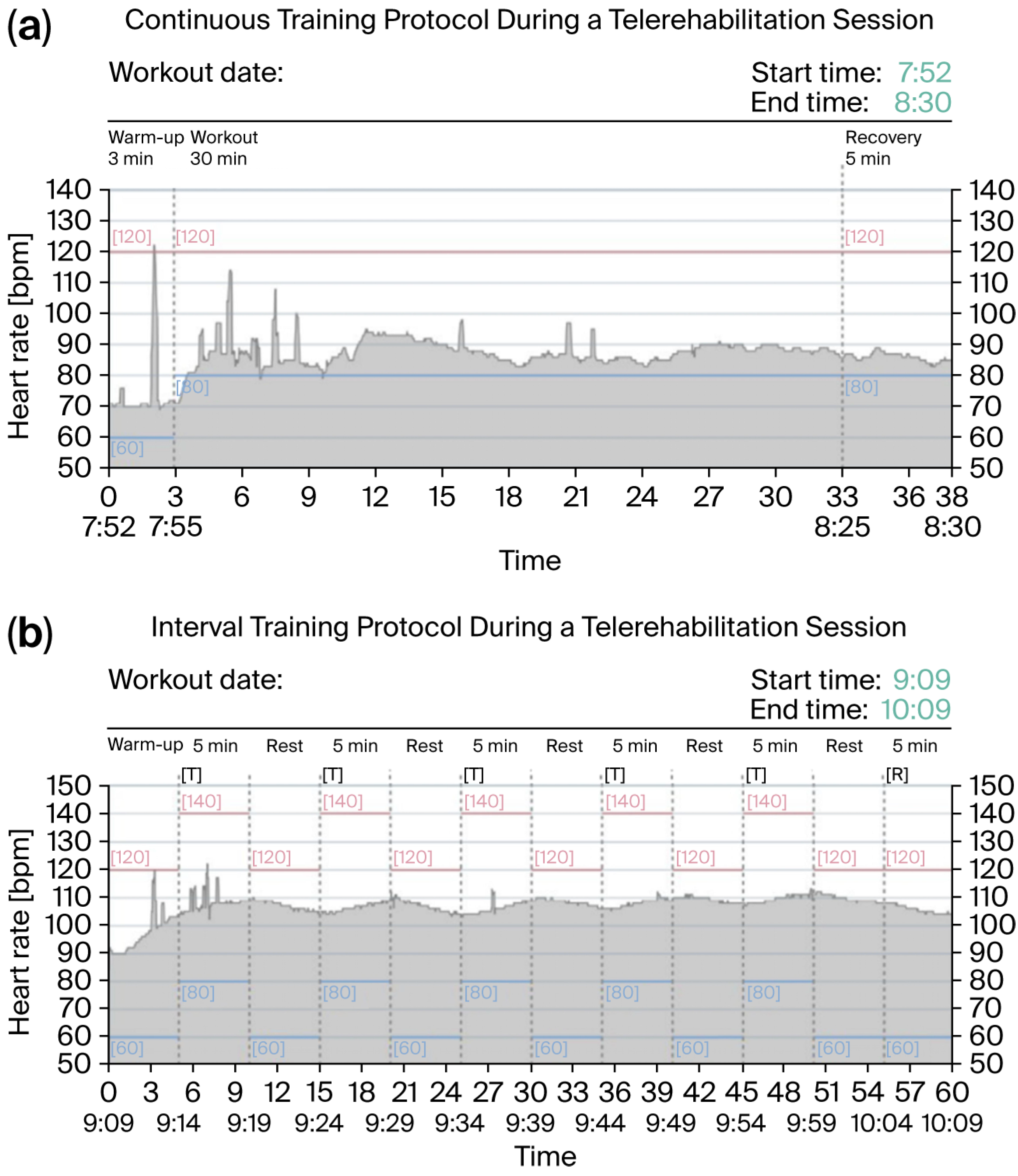

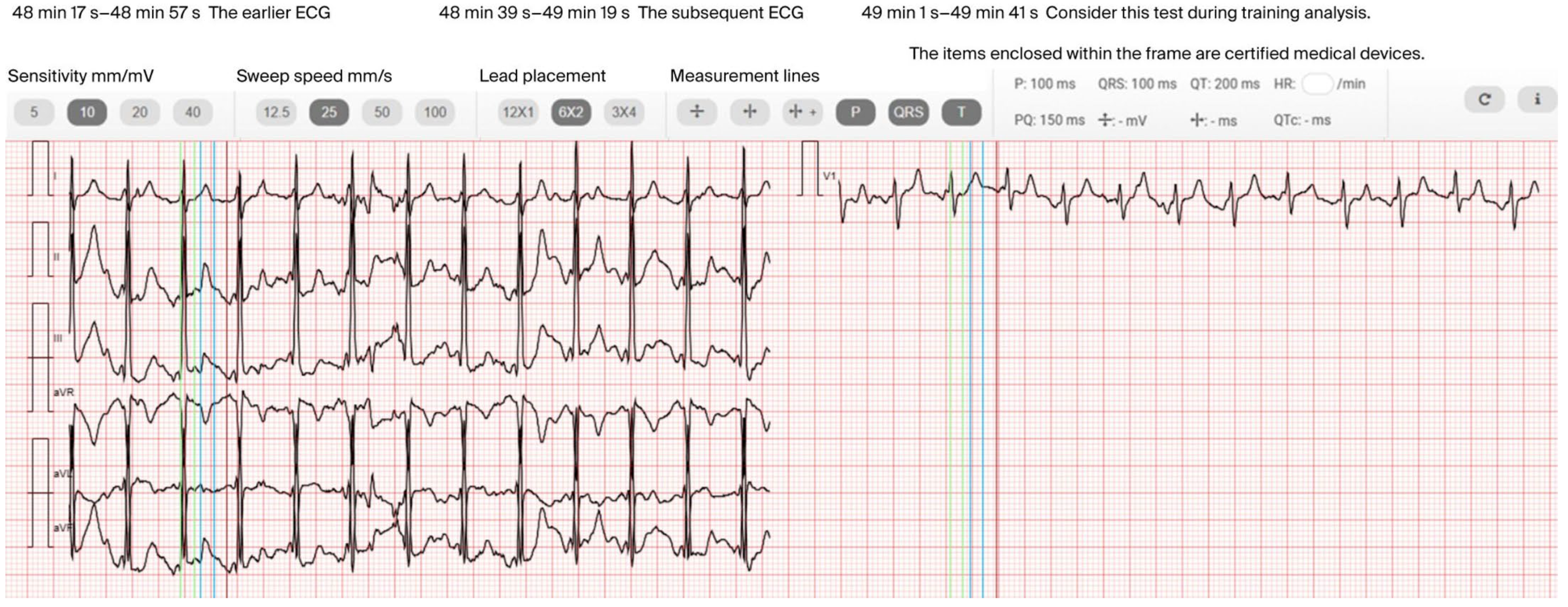

2.5. Program Protocol of Home-Based Telerehabilitation

2.6. Clinical Assessment

2.7. Psychological Support

2.8. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

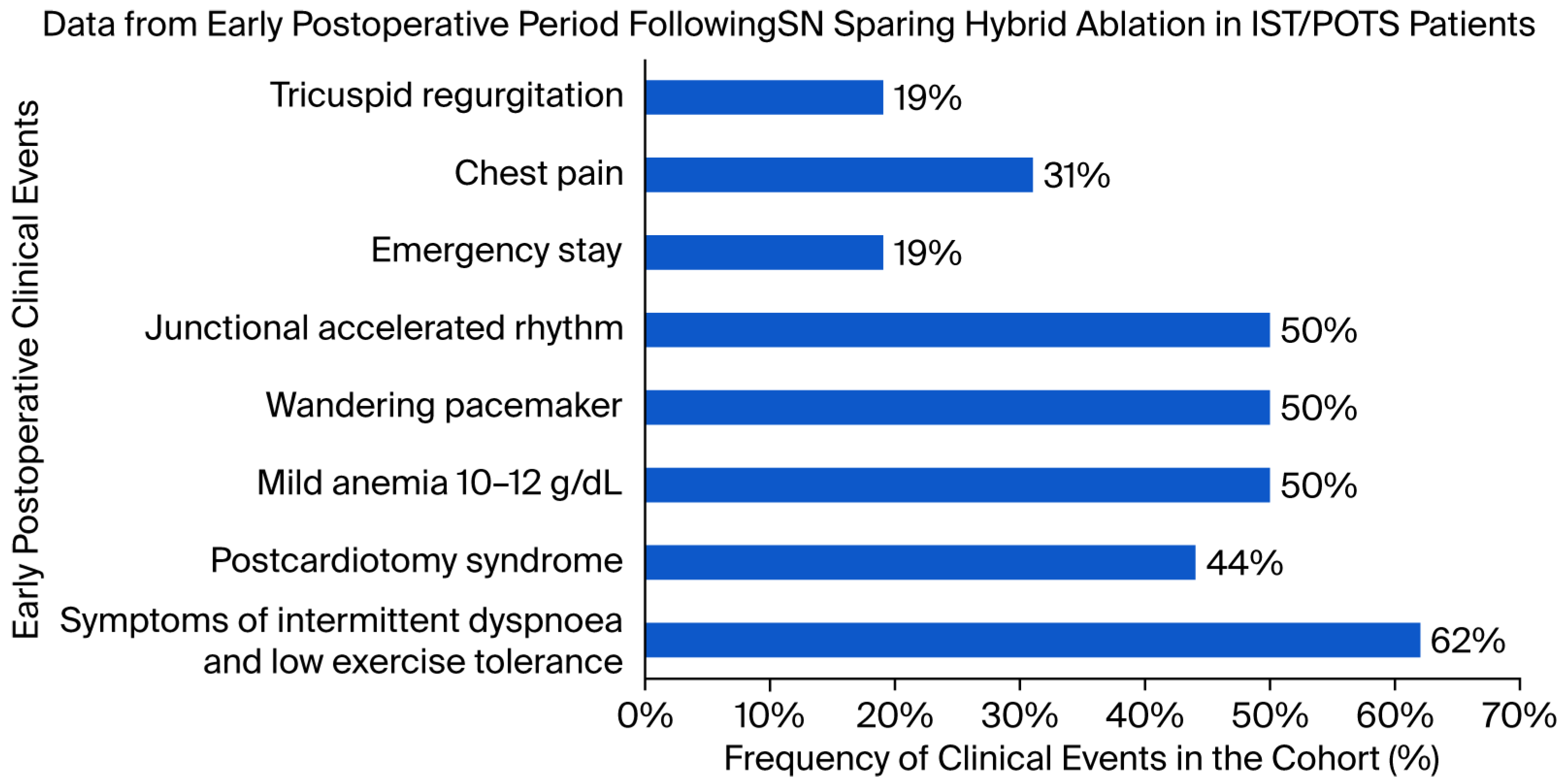

3.1. Implementation of Inpatient Rehabilitation and Early Clinical Events

3.2. Efficacy of Inpatient Rehabilitation

3.3. Implementation and Acceptance of the Home-Based Telerehabilitation

3.4. Adherence to Home-Based Telerehabilitation

3.5. Clinical Assessment

3.6. Psychological Support

4. Discussion

4.1. Clinical Implications of the Inpatient Rehabilitation Protocol

4.2. Insights from the Home-Based Telerehabilitation Protocol

4.3. Interpretation of the Clinical Assessment

4.4. Role of Psychological Support

5. Limitations

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mayuga, K.A.; Fedorowski, A.; Ricci, F.; Gopinathannair, R.; Dukes, J.W.; Gibbons, C.; Hanna, P.; Sorajja, D.; Chung, M.; Benditt, D.; et al. Sinus Tachycardia: A Multidisciplinary Expert Focused Review. Circ. Arrhythm. Electrophysiol. 2022, 15, e007960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fedorowski, A.; Fanciulli, A.; Raj, S.R.; Sheldon, R.; Shibao, C.A.; Sutton, R. Cardiovascular autonomic dysfunction in post-COVID-19 syndrome: A major health-care burden. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2024, 21, 379–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Q.; Levine, B.D. Exercise and non-pharmacological treatment of POTS. Auton. Neurosci. 2018, 215, 20–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abed, H.S.; Fulcher, J.R.; Kilborn, M.J.; Keech, A.C. Inappropriate sinus tachycardia: Focus on ivabradine. Intern. Med. J. 2016, 46, 875–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, A.; Pothineni, N.V.K.; Charate, R.; Garg, J.; Elbey, M.; de Asmundis, C.; LaMeir, M.; Romeya, A.; Shivamurthy, P.; Olshansky, B.; et al. Inappropriate Sinus Tachycardia: Etiology, Pathophysiology, and Management: JACC Review Topic of the Week. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2022, 79, 2450–2462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanjwal, K.; Karabin, B.; Sheikh, M.; Elmer, L.; Kanjwal, Y.; Saeed, B.; Grubb, B.P. Pyridostigmine in the treatment of postural orthostatic tachycardia: A single-center experience. Pacing Clin. Electrophysiol. 2011, 34, 750–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakkireddy, D.; Garg, J.; DeAsmundis, C.; LaMeier, M.; Romeya, A.; Vanmeetren, J.; Park, P.; Tummala, R.; Koerber, S.; Vasamreddy, C.; et al. Sinus Node Sparing Hybrid Thoracoscopic Ablation Outcomes in Patients with Inappropriate Sinus Tachycardia (SUSRUTA-IST) Registry. Heart Rhythm 2022, 19, 30–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Asmundis, C.; Chierchia, G.B.; Lakkireddy, D.; Romeya, A.; Okum, E.; Gandhi, G.; Sieira, J.; Vloka, M.; Jones, S.D.; Shah, H.; et al. Sinus node sparing novel hybrid approach for treatment of inappropriate sinus tachycardia/postural sinus tachycardia: Multicenter experience. J. Interv. Card. Electrophysiol. 2022, 63, 531–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Asmundis, C.; Pannone, L.; Lakkireddy, D.; Beaver, T.M.; Brodt, C.R.; Lee, R.J.; Frazier, K.; Chierchia, G.-B.; La Meir, M. Hybrid epicardial and endocardial sinus node-sparing ablation therapy for inappropriate sinus tachycardia: Rationale and design of the multicenter HEAL-IST IDE trial. Heart Rhythm O2 2023, 4, 275–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spahic, J.M.; Hamrefors, V.; Johansson, M.; Ricci, F.; Melander, O.; Sutton, R.; Fedorowski, A. Malmö POTS symptom score: Assessing symptom burden in postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome. J. Intern. Med. 2023, 293, 91–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fedorowski, A. Postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome: Clinical presentation, aetiology and management. J. Intern. Med. 2019, 285, 352–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, R.L.; Joglar, J.A.; Caldwell, M.A.; Calkins, H.; Conti, J.B.; Deal, B.J.; Mark Estes, N.A., III; Field, M.E.; Goldberger, Z.D.; Hammill, S.C.; et al. 2015 ACC/AHA/HRS Guideline for the Management of Adult Patients With Supraventricular Tachycardia: Executive Summary: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines and the Heart Rhythm Society. Circulation 2016, 133, e471–e505, Erratum in Circulation 2016, 134, e232–e233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brugada, J.; Katritsis, D.G.; Arbelo, E.; Arribas, F.; Bax, J.J.; Blomström-Lundqvist, C.; Calkins, H.; Corrado, D.; Deftereos, S.G.; Diller, G.P.; et al. 2019 ESC Guidelines for the management of patients with supraventricular tachycardia The Task Force for the management of patients with supraventricular tachycardia of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur. Heart J. 2020, 41, 655–720, Erratum in Eur. Heart J. 2020, 41, 4258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Asmundis, C.; Marcon, L.; Pannone, L.; Della Rocca, D.G.; Lakkireddy, D.; Beaver, T.M.; Brodt, C.R.; Monaco, C.; Sorgente, A.; Audiat, C.; et al. Pericarditis prophylactic therapy after sinus node-sparing hybrid ablation for inappropriate sinus tachycardia/postural orthostatic sinus tachycardia. Heart Rhythm O2 2024, 5, 137–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pelliccia, A.; Sharma, S.; Gati, S.; Bäck, M.; Börjesson, M.; Caselli, S.; Collet, J.P.; Corrado, D.; Drezner, J.A.; Halle, M.; et al. 2020 ESC Guidelines on sports cardiology and exercise in patients with cardiovascular disease. Eur. Heart J. 2021, 42, 17–96, Erratum in Eur. Heart J. 2021, 42, 548–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piepoli, M.F.; Conraads, V.; Corrà, U.; Dickstein, K.; Francis, D.P.; Jaarsma, T.; McMurray, J.; Pieske, B.; Piotrowicz, E.; Schmid, J.-P.; et al. Exercise training in heart failure: From theory to practice. A consensus document of the Heart Failure Association and the European Association for Cardiovascular Prevention and Rehabilitation. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 2011, 13, 347–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taylor, J.L.; Myers, J.; Bonikowske, A.R. Practical guidelines for exercise prescription in patients with chronic heart failure. Heart Fail. Rev. 2023, 28, 1285–1296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piotrowicz, E.; Zieliński, T.; Bodalski, R.; Rywik, T.; Dobraszkiewicz-Wasilewska, B.; Sobieszczańska-Małek, M.; Stepnowska, M.; Przybylski, A.; Browarek, A.; Szumowski, Ł.; et al. Home-based telemonitored Nordic walking training is well accepted, safe, effective and has high adherence among heart failure patients, including those with cardiovascular implantable electronic devices: A randomised controlled study. Eur. J. Prev. Cardiol. 2015, 22, 1368–1377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antoniou, V.; Davos, C.H.; Kapreli, E.; Batalik, L.; Panagiotakos, D.B.; Pepera, G. Effectiveness of Home-Based Cardiac Rehabilitation, Using Wearable Sensors, as a Multicomponent, Cutting-Edge Intervention: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 3772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piotrowicz, E.; Mierzyńska, A.; Jaworska, I.; Opolski, G.; Banach, M.; Zaręba, W.; Kowalik, I.; Pencina, M.; Orzechowski, P.; Szalewska, D.; et al. Relationship between physical capacity and depression in heart failure patients undergoing hybrid comprehensive telerehabilitation vs. usual care: Subanalysis from the TELEREH-HF Randomized Clinical Trial. Eur. J. Cardiovasc. Nurs. 2022, 21, 568–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grubb, B.P.; Kanjwal, Y.; Kosinski, D.J. The postural tachycardia syndrome: A concise guide to diagnosis and management. J. Cardiovasc. Electrophysiol. 2006, 17, 108–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, C.R.; Olshansky, B.; Cortez, D.; Duval, S.; Benditt, D.G. Inappropriate sinus tachycardia: An examination of existing definitions. Europace 2022, 24, 1655–1664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stec, S.; Suwalski, P.; De Asmundis, C.; La Meir, M.; Reichert, A.; Wilczek-Banc, A.; Szkaradek, B.; Kowalewski, M. EP-Heart Team approach with sinus node sparing ablation for complex inappropriate sinus tachycardia and postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome: A first experience in Central Europe. Kardiol. Pol. 2025, 83, 342–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, R.S.; Blakemore, A. Exercise-based cardiac rehabilitation: The importance of home-based approaches. Eur. Heart J. 2025, 46, 2202–2204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aerts, L.; Kawczynski, M.J.; Bidar, E.; Luermans, J.G.L.; Chaldoupi, S.-M.; La Meir, M.; Kowalewski, M.; Maessen, J.G.; Heuts, S.; Maesen, B. Short- and long-term outcomes in isolated vs. hybrid thoracoscopic ablation in patients with atrial fibrillation: A systematic review and reconstructed individual patient data meta-analysis. Europace 2024, 26, euae232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jafri, S.H.; Guglin, M.; Rao, R.; Ilonze, O.; Ballut, K.; Baloch, Z.Q.; Qintar, M.; Cohn, J.; Wilcox, M.; Freeman, A.M.; et al. Intensive Cardiac Rehabilitation Outcomes in Patients with Heart Failure. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 6886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El-Rhermoul, F.-Z.; Fedorowski, A.; Eardley, P.; Taraborrelli, P.; Panagopoulos, D.; Sutton, R.; Lim, P.B.; Dani, M. Autoimmunity in Long Covid and POTS. Oxf. Open Immunol. 2023, 4, iqad002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stec, S.; Suwalski, P.; de Asmundis, C.; LaMeir, M.; Kwaśniak, E.; Ogorzelec, N.; Reichert, A.; Wilczek-Banc, A.; Szkaradek, B.; Kowalewski, M. Hybrid sinus node sparing ablation for complex inappropriate sinus tachycardia and postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome: Initial experience in Central Europe. Pol. Arch. Intern. Med. 2025, 135, 17014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heindl, B.; Ramirez, L.; Joseph, L.; Clarkson, S.; Thomas, R.; Bittner, V. Hybrid cardiac rehabilitation—The state of the science and the way forward. Prog. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2022, 70, 175–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kornaszewska, M.; Wilczek-Banc, A.; Ratajska, A.; Piotrowicz, E.; Szkaradek, B.; Kowalewski, M.; Suwalski, P.; Ogorzelec, N.; Wileczek, A.; Zając, M.; et al. Implementation of a Hybrid Cardiac Rehabilitation and Symptom Scoring System in Patients with Inappropriate or Postural Sinus Tachycardia Referred for Sinus Node Sparing Hybrid Ablation. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 5879. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14165879

Kornaszewska M, Wilczek-Banc A, Ratajska A, Piotrowicz E, Szkaradek B, Kowalewski M, Suwalski P, Ogorzelec N, Wileczek A, Zając M, et al. Implementation of a Hybrid Cardiac Rehabilitation and Symptom Scoring System in Patients with Inappropriate or Postural Sinus Tachycardia Referred for Sinus Node Sparing Hybrid Ablation. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(16):5879. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14165879

Chicago/Turabian StyleKornaszewska, Marta, Aleksandra Wilczek-Banc, Anna Ratajska, Ewa Piotrowicz, Bartosz Szkaradek, Mariusz Kowalewski, Piotr Suwalski, Natalia Ogorzelec, Antoni Wileczek, Magdalena Zając, and et al. 2025. "Implementation of a Hybrid Cardiac Rehabilitation and Symptom Scoring System in Patients with Inappropriate or Postural Sinus Tachycardia Referred for Sinus Node Sparing Hybrid Ablation" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 16: 5879. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14165879

APA StyleKornaszewska, M., Wilczek-Banc, A., Ratajska, A., Piotrowicz, E., Szkaradek, B., Kowalewski, M., Suwalski, P., Ogorzelec, N., Wileczek, A., Zając, M., Pastyrzak, M., & Stec, S. (2025). Implementation of a Hybrid Cardiac Rehabilitation and Symptom Scoring System in Patients with Inappropriate or Postural Sinus Tachycardia Referred for Sinus Node Sparing Hybrid Ablation. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(16), 5879. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14165879